The Project Gutenberg EBook of Casell's Book of Birds, by

Thomas Rymer Jones and Alfred Edmund Brehm

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Casell's Book of Birds

Volume 3 (of 4)

Author: Thomas Rymer Jones

Alfred Edmund Brehm

Release Date: September 7, 2019 [EBook #60254]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CASELL'S BOOK OF BIRDS ***

Produced by Jane Robins and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Plate 21, Cassell's Book of Birds

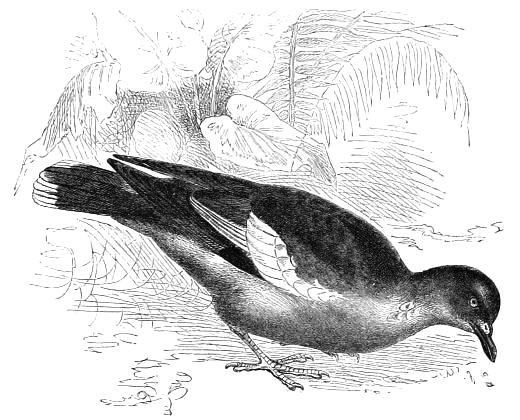

THE BLUE GRANDALA ____ Grandala Coelicolor

about 2⁄3 Nat. size

FROM THE TEXT OF DR. BREHM.

BY

THOMAS RYMER JONES, F.R.S.,

PROFESSOR OF NATURAL HISTORY AND COMPARATIVE ANATOMY IN KING'S COLLEGE, LONDON.

WITH UPWARDS OF

Four Hundred Engravings, and a Series of Coloured Plates.

IN FOUR VOLUMES.

VOL. III.

LONDON:

CASSELL, PETTER, AND GALPIN;

AND NEW YORK

——♦——

PAGE

THE CLIMBERS. The CLIMBING BIRDS (Scansor):—The Tenuirostral. The FLOWER BIRDS (Certhiola). The BLUE BIRDS (Cæreba):—The Sai, or Blue Caereba. The PITPITS (Certhiola):—The Banana Quit, or Black and Yellow Creeper. The HONEYSUCKERS (Nectarinia):—The Abu-Risch. The FIRE HONEYSUCKERS (Æthopyga):—The Cadet. The BENT-BEAKS (Cyrtostomus):—The Australian Blossom Rifler. The SPIDER-EATERS (Arachnothera). The HALF-BILLS (Hemignathus):—The Brilliant Half-bill. The HANGING BIRDS (Arachnocestra):—The True Hanging Bird. The HONEY-EATERS (Meliphaga). The TRUE HONEY-EATERS (Myzomela):—The Red-headed Honey-eater. The TUFTED HONEY-EATERS (Ptilotis):—The Yellow-throated Tufted Honey-eater. The BRUSH WATTLE BIRDS (Melichæra):—The True Brush Wattle Bird—The Poe, or Tui. The FRIAR BIRDS (Tropidorhyncus):—The "Leatherhead." The HOOPOES (Upupa):—The Common Hoopoe. The TREE HOOPOES (Irrisor):—The Red-beaked Tree Hoopoe 1–15THE TREE CLIMBERS (Anabata). The BUNDLE-NESTS (Phacellodomus):—The Red-fronted Bundle-nest, or Climbing Thrush. The OVEN BIRDS (Furnarius):—The Red Oven Bird. The GROUND WOODPECKERS (Geositta):—The Burrowing Ground Woodpecker. The STAIR-BEAKS (Xenops);—The Hairy-cheeked Stair-beak. THE NUTHATCHES (Sitta)—The Common Nuthatch—The Syrian Nuthatch. The CREEPERS (Sittella):—The Bonneted Creeper. The WALL CREEPERS (Tichodroma):—The Alpine or Red-winged Wall Creeper. The TRUE TREE CREEPERS (Certhia):—The Tree Peckers. TREE CLIMBERS (Scandentes):—The Common Tree Creeper—The Sabre-bill—The Woodpecker Tree-chopper. The WOODPECKERS (Picida). The BLACK WOODPECKERS (Dryocopus):—The European Black Woodpecker. The GIANT WOODPECKERS (Campephilus):—The Imperial Woodpecker—The Ivory-billed Woodpecker. The BLACK WOODPECKERS (Melanerpes):—The Red-headed Black Woodpecker—The Ant-eating Black Woodpecker. The VARIEGATED WOODPECKERS (Picus):—The Great Spotted Woodpecker—The Harlequin Woodpecker—The Three-toed Woodpecker. The GREEN WOODPECKERS (Cecinus):—The Green Woodpecker. The CUCKOO WOODPECKERS (Colaptes):—The Golden-winged Woodpecker—The Red-shafted or Copper Woodpecker—The Field Woodpecker. The SOFT-TAILED WOODPECKERS (Picumnus):—The Dwarf Woodpecker. The WRY-NECKS (Yunx):—The Wry-neck 15–45

HUMMING BIRDS. The HUMMING BIRDS (Stridor). The GIANT GNOMES (Eustephanus):—The Giant Humming Bird—The Sword-bill Humming Bird. The GNOMES (Polytmus):—The Saw-bill—The Sickle-billed Humming Bird. The SUN BIRDS (Phäetornis):—The Cayenne Hermit. The MOUNTAIN NYMPHS (Oreotrochilus):—The Chimborazian Hill-star. The SABRE-WINGS (Campylopterus):—De Lattrei's Sabre-wing. The TRUE SABRE-WINGS (Platystylopterus):—The Fawn-coloured Sabre-wing. The JEWEL HUMMING BIRDS (Hypophania):—The Crimson Topaz Humming Bird—The Black-capped Humming Bird. The WOOD NYMPHS (Lampornis):—The Mango Humming Bird—The Ruby and Topaz Wood Nymph. The FLOWER NYMPHS (Florisugus):—The Brazilian Fairy. The FLOWER SUCKERS (Florisuga):—The Pied Jacobin. THE FAIRIES (Trochilus):—The Ruby-throated Fairy Humming Bird. The AMETHYST HUMMING BIRDS (Calliphlox):—The Amethyst Humming Bird. The WOODSTARS[iv] (Calothorax, or Lucifer):—Mulsant's Wood-star. The ELVES (Lophornithes). The PLOVER-CRESTS (Cephalolepis):—De Laland's Plover-crest. The COQUETTES (Lophornis):—The Splendid Coquette. The AMAZONS (Bellatrix):—The Royal Amazon. The SUN GEMS (Heliactinus):—The Horned Sun Gem. The SYLPHS (Lesbiæ). The RACKET-TAILED SYLPHS (Steganurus):—The White-footed Racket-tail. The COMETS (Sparganura):—The Sappho Comet. The MASKED HUMMING BIRDS (Microrhamphi):—The Sharp-bearded Masked Humming Bird—The Columbian Thornbill. The HELMET CRESTS (Oxypogon):—Linden's Helmet Crest 45–75

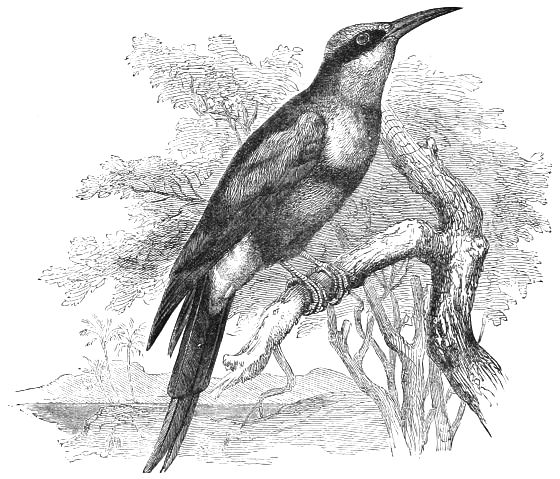

THE LIGHT-BEAKS (Levirostres). The BEE-EATERS (Meropes):—The Common Bee-eater—The Bee-wolf—The Bridled Bee-eater—The Swallow Bee-eater—The Australian Bee-eater. The NOCTURNAL BEE-EATERS (Nyctiornis):—The Sangrok. The ROLLERS (Coracii):—The Blue Roller. The DOLLAR BIRDS (Eurystomus):—The Australian Dollar Bird—The Oriental Dollar Bird. The SAW-BILL ROLLERS (Prionites):—The Mot-mot. The BROAD-THROATS (Eurylaimus):—The Sumatran Trowel-beak. The TRUE BROAD-THROATS (Eurylaimus):—The Java Broad-throat—The Raya. The TODIES (Todi):—The Tody, or Green Flat-bill 75–87

THE KINGFISHERS (Alcedines):—The European Kingfisher. The PURPLE KINGFISHERS (Ceyx):—The Purple Kingfisher. The GREY KINGFISHERS (Ceryle):—The Grey Kingfisher 87–91

THE ALCYONS (Halcyones). The TREE ALCYONS (Halcyones):—The Red-breasted Tree Alcyon. The WOOD ALCYON (Todiramphus):—The Yellow-headed Wood Alcyon—The Blue Alcyon. The GIANT ALCYONS (Paralcyon, or Dacelo):—The Laughing Jackass, or Settler's Clock. The PARADISE ALCYONS (Tanysiptera):—The True Paradise Alcyon. The SAW-BEAKED ALCYONS (Syma):—The Poditti. The SLUGGARDS (Agornithes). The JACAMARS (Galbulæ):—The True Jacamars—The Green Jacamar 91-96

THE BUCCOS (Buccones). The SLEEPERS (Nystalus):—The Tschakuru. The TRAPPISTS (Monasta):—The Dusky Trappist, or Bearded Cuckoo. The DREAMERS (Chelidoptera):—The Dark Dreamer. The TOURACOS, or TROGONS (Trogones). The FIRE TOURACOS (Harpactes):—The Karna, or Malabar Trogon. The FLOWER TOURACOS (Hapaloderma):—The Narina. The TROGONS PROPER (Trogon):—The Surukua, or Touraco—The Pompeo—The Tocoloro. The BEAUTIFUL-TAILED TROGONS (Calurus):—The Peacock Trogon—The Beautiful Trogon—The Quesal, or Resplendent Trogon 96–105

THE CUCKOOS (Cuculidæ). The HONEY GUIDES (Indicator):—The White-beaked Honey Guide. The CUCKOOS (Cuculus):—The Common Cuckoo. The JAY CUCKOOS (Coccystes):—The Jay Cuckoo. The KOELS (Eudynamys):—The Koel, or Kuil. The GOLDEN CUCKOOS (Chrysococcyx):—The Didrik, or Golden Cuckoo. The GIANT CUCKOOS (Scythrops):—The Giant Cuckoo, or Channel-bill. The BUSH CUCKOOS (Phœnicophæi):—The Kokil, or Large Green-billed Malkoha. The RAIN CUCKOOS (Coccygi):—The Rain or Yellow-billed Cuckoo—The Rain Bird. The LONG-TAILED CUCKOOS (Pyrrhococcyx):—The Long-tailed Cuckoo. The TICK-EATERS (Crotophagæ). The TRUE TICK-EATERS (Crotophaga):—The Coroya—The Ani, or Savanna Blackbird—The Wrinkled-beaked Tick-eater. The COUCALS, or SPURRED CUCKOOS (Centropodes):—The Egyptian Coucal. The CROW PHEASANTS (Centrococcyx):—The Hedge Crow. The PHEASANT COUCALS (Polophilus):—The Pheasant Coucal. The BARBETS (Capitones):—The Pearl Bird—The Golden Barbet—The Toucan Barbet 105–127

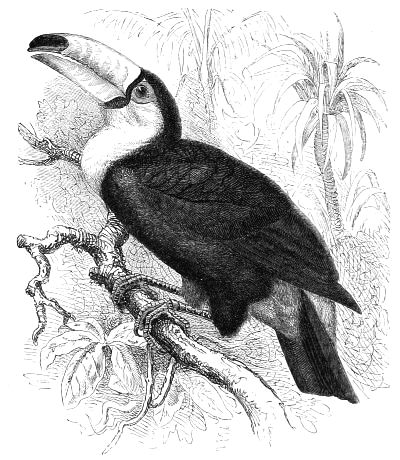

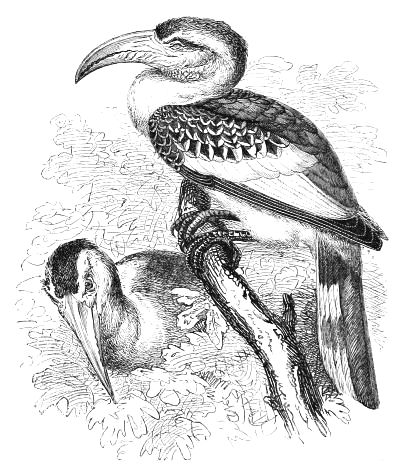

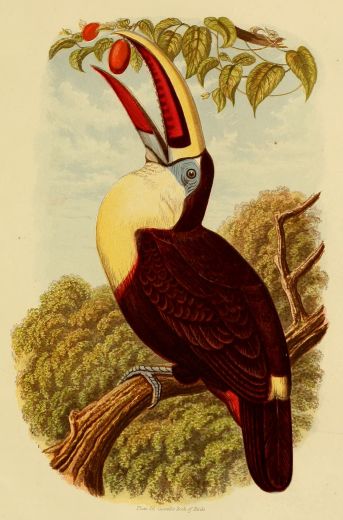

THE HORNBILLS (Bucerotidæ). The TOUCANS (Ramphastidæ). The ARASSARIS (Pteroglossus):—The Arassari. The TOUCANS PROPER (Ramphastus):—The Toco Toucan—The Kirima, or Red-billed Toucan—The Tukana. The HORNBILLS PROPER (Bucerotes). The SMOOTH-BEAKED HORNBILLS (Rhynchaceros):—The Tok. The TWO-HORNED HORNBILLS (Dichoceros):—The Homray—The Djolan, or Year Bird—The Abbagamba, or Abyssinian Hornbill 127–140

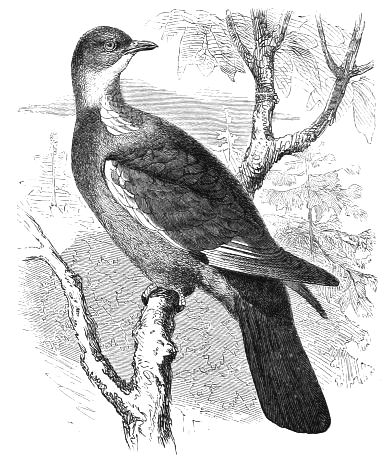

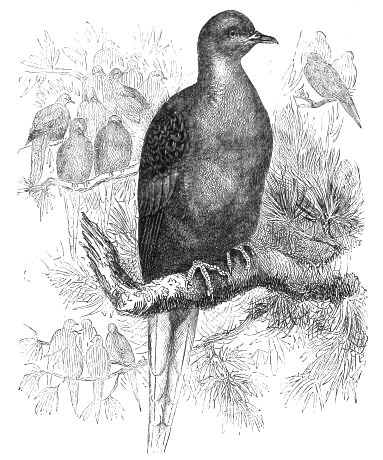

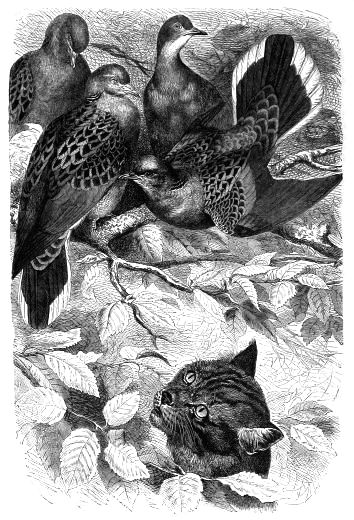

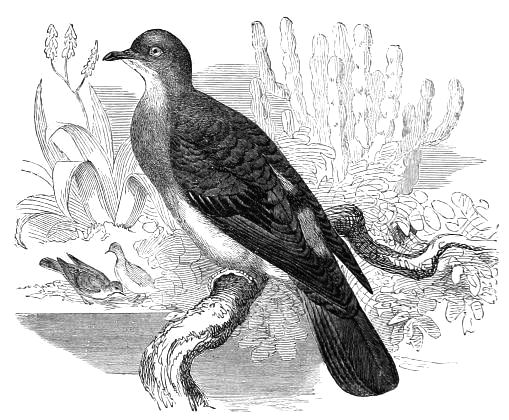

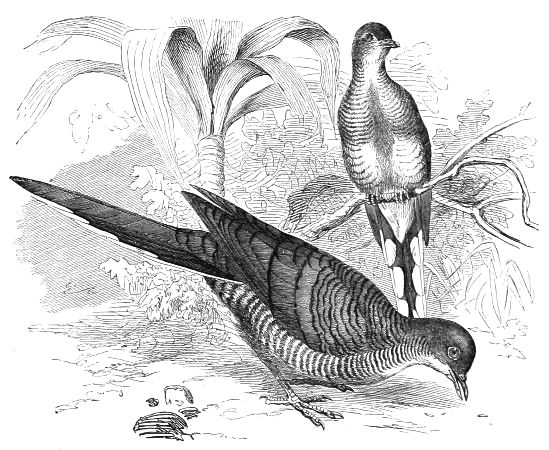

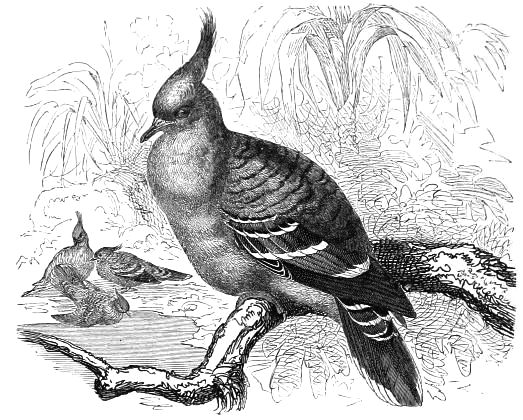

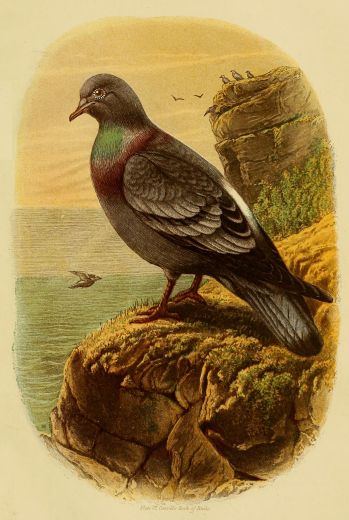

PIGEONS (Gyratores). The FRUIT PIGEONS (Trerones):—The Parrot Pigeon. The DOVES (Columbæ):—The Ring-dove, Wood Pigeon, or Cushat—The Stock Dove—The Rock Dove. The CUCKOO PIGEONS (Macropygiæ):—The Passenger Pigeon, or Carolina Turtle-dove. The TURTLE-DOVES (Turtures):—The Turtle-dove. The INDIAN RING-DOVES (Streptopeleia):—The Indian Ring-dove—The Dwarf Pigeon. The GROUND PIGEONS. The AMERICAN GROUND PIGEONS (Zenaidæ). The SINGING DOVES (Melopeleia):—The Kukuli. The SPARROW PIGEONS (Pyrgitœnas):—The Sparrow Pigeon, or Ground Dove. The SPARROW-HAWK PIGEONS (Geopeleia):—The Striped Sparrow-hawk Pigeon—The Speckled or Wedge-tailed Turtle-dove. The RUNNING PIGEONS (Geotrygones):—The Partridge Dove. The BRONZE-WINGED PIGEONS (Phapes):—The Crested Bronze-wing. The TRUE BRONZE-WINGS (Phaps):—The Common Bronze-wing 141–166

THE QUAIL PIGEONS (Geophaps):—The Partridge Bronze-wing. The WHITE-FLESHED PIGEONS (Leucosarcia):—The Wonga-Wonga Pigeon—The Hackled Ground Pigeon. The CROWNED PIGEONS (Gouræ):—The Crowned Pigeon—The Victoria Crowned Pigeon—The Didunculus, or Toothed Pigeon 166–172

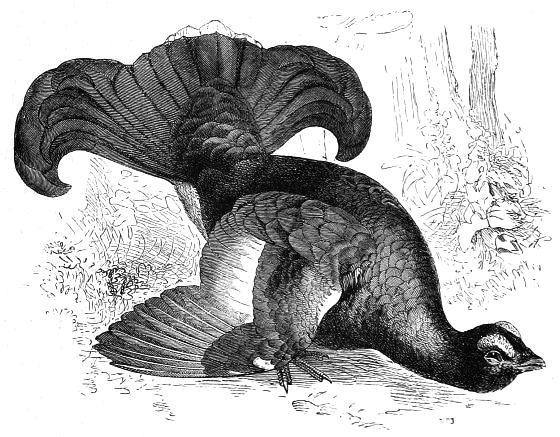

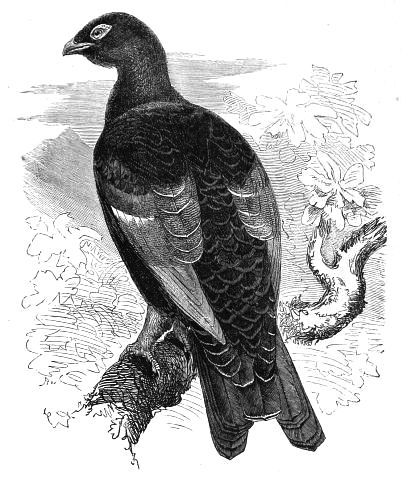

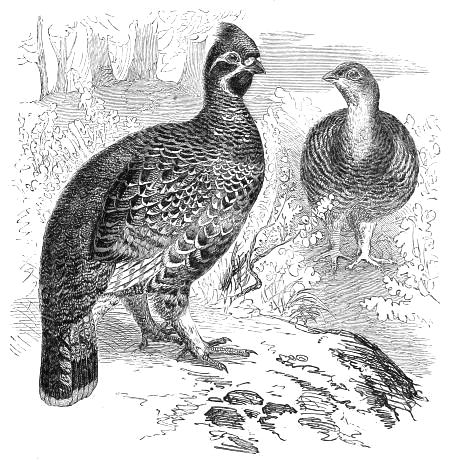

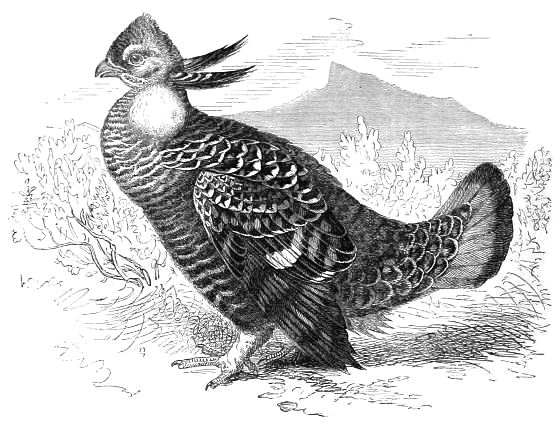

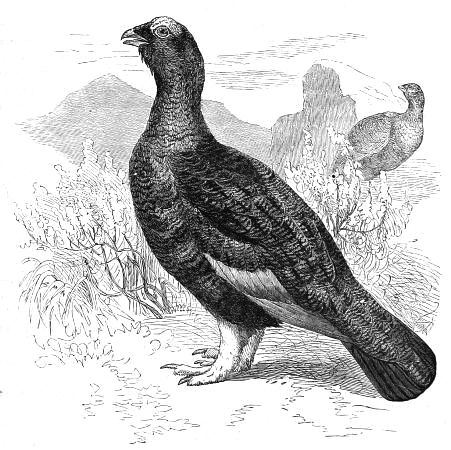

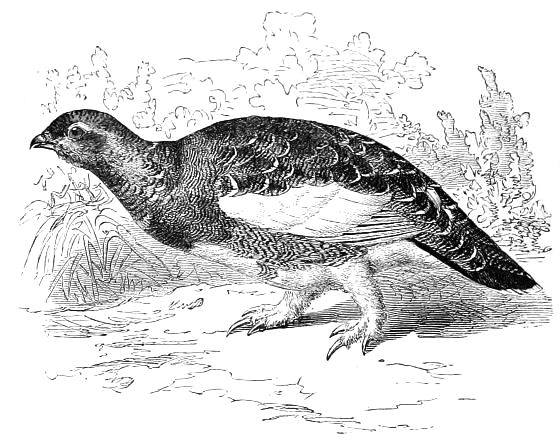

TRUE GALLINACEOUS BIRDS. The SAND GROUSE (Pteroclæ):—The Ganga, or Large Sand Grouse—The Large Pin-tailed Grouse, or Khata—The Common Sand Grouse—The Striped Sand Grouse—Pallas's Sand Grouse. The GROUSE TRIBE (Tetraonidæ). The GROUSE PROPER (Tetraones):—The Capercali. The HEATH COCKS (Lyrurus):—The Black Cock—The Hybrid Grouse—The Hazel Grouse—The Prairie Hen, or Pinnated Grouse 172-195

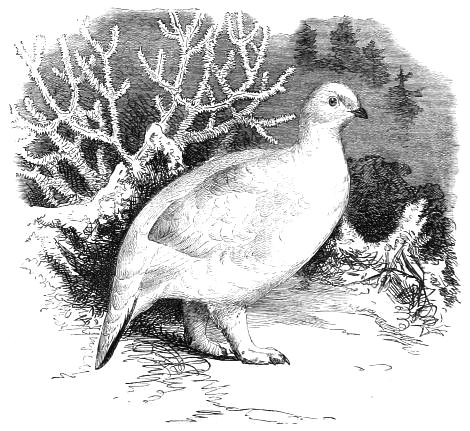

THE PTARMIGANS (Lagopus):—The Willow Ptarmigan—The Alpine or Grey Ptarmigan—The Red Grouse, Brown Ptarmigan, or Gar Cock 195–202

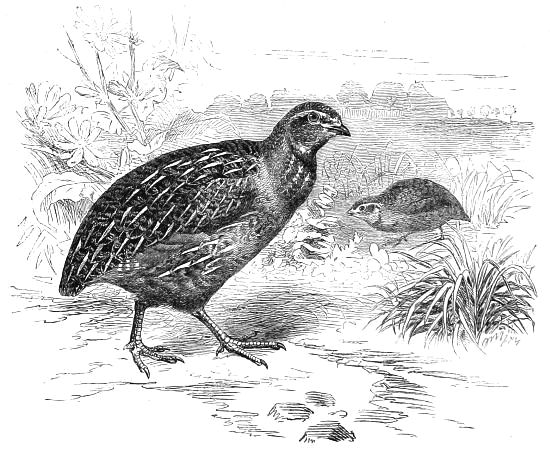

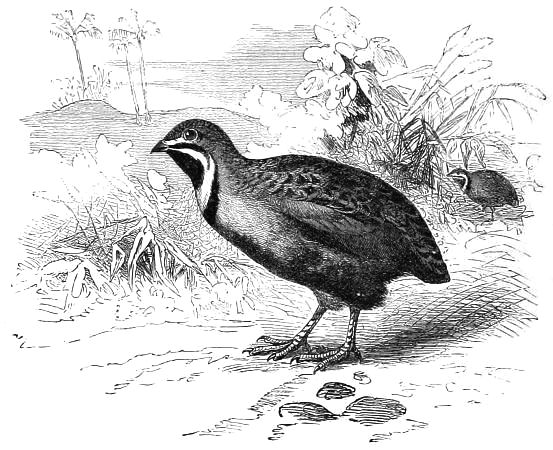

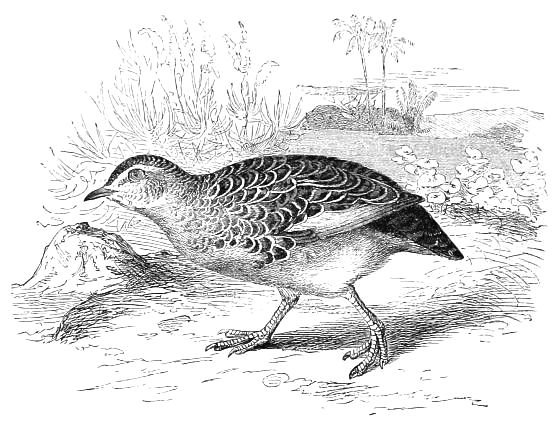

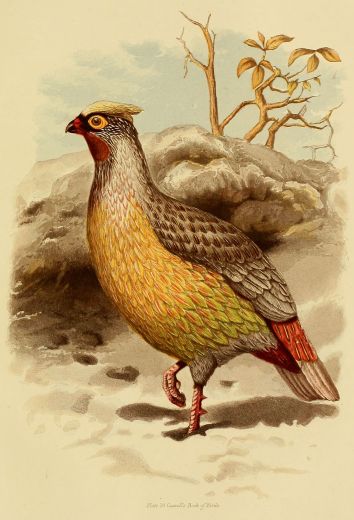

THE PARTRIDGES (Perdices). The SNOW PARTRIDGES (Tetraogallus):—The Caspian Snow Partridge—The Himalayan Snow Cock, or Snow Pheasant. The RED-LEGGED PARTRIDGES (Caccabis):—The Greek Partridge—The Chuckore—The Red-legged Partridge—The Barbary Partridge—The Common Partridge. The FRANCOLINS (Francolinus):—The Black Partridge. The BARE-NECKED PHEASANTS (Pternistes):—The Red-necked Pheasants. The AMERICAN PARTRIDGES (Odontophori):—The Capueira Partridge—The Virginian or American Partridge. The CALIFORNIAN PARTRIDGE (Lophortyx Californianus) and GAMBEL'S PARTRIDGE (Lophortyx Gambelii):—The Californian Partridge—Gambel's Partridge. The QUAILS (Coturnices):—The Common Quail. The DWARF QUAILS (Excalfactoria):—The Chinese Quail. The BUSH QUAIL (Turnices):—The Black-breasted Bustard Quail—The African Bush Quail—The Collared Plain-wanderer 202–228

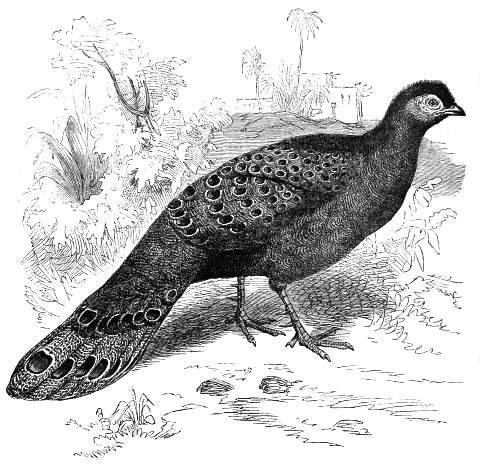

THE PHASIANIDÆ. The TUFTED PHEASANTS (Lophophori):—The Monaul or Impeyan Pheasant—Lhuys' Pheasant. The TRAGOPANS, or HORNED PHEASANTS (Ceriornis):—The Sikkim Horned Pheasant—The Jewar, or Western Horned Pheasant. The JUNGLE FOWLS (Galli):—Kasintu, or Red Jungle Fowl—The Jungle Fowl of Ceylon—The Javanese Jungle Fowl—The Sonnerat Jungle Fowl, or Katakoli. The MACARTNEY PHEASANTS (Euplocamus):—The Siamese Fireback—The Sikkim Kaleege, or Black Pheasant—The Kelitsch, or White-crested Kaleege Pheasant—The Silver Pheasant. The PHEASANTS PROPER (Phasiani):—The Common Pheasant—The Chinese Ring-necked Pheasant—The Japanese Pheasant—Soemmerring's Pheasant—Reeves' Pheasant. The GOLDEN PHEASANTS (Thaumalea):—The Golden Pheasant—Lady Amherst's Pheasant. The EARED PHEASANTS (Crossoptilon):—The Chinese Eared Pheasant—The Argus Pheasant, or Kuau. The PEACOCK PHEASANTS (Polyplectron):—The Chinquis, or Assam Peacock Pheasant. The PEACOCKS (Pavones):—The Common Peacock—The Black-winged Peacock—The Japan Peacock. The GUINEA FOWLS (Numidæ). The ROYAL GUINEA FOWLS (Acryllium):—The Vulturine Royal Guinea Fowl 228–257

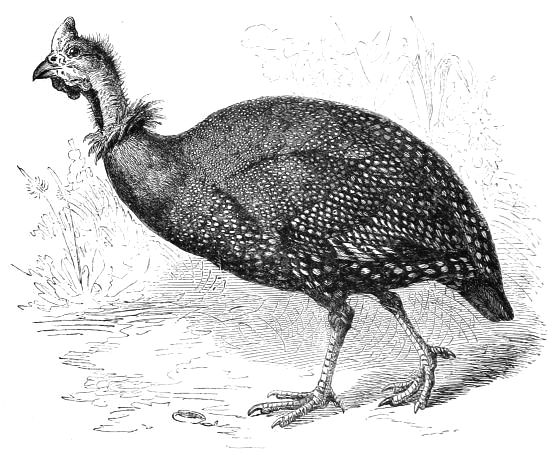

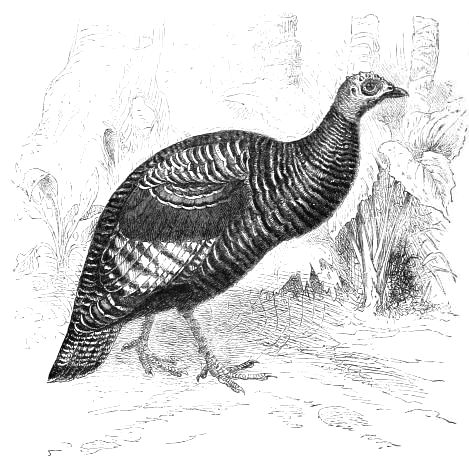

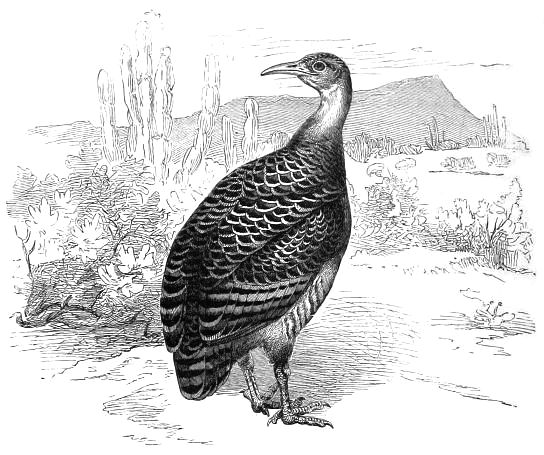

THE TUFTED GUINEA FOWLS (Guttera):—Pucheran's Tufted Guinea Fowl. The GUINEA FOWLS (Numida):—The Common Guinea Fowl—The Mitred Pintado—The Tuft-beaked Pintado. The TURKEYS (Meleagrides):—The Puter, or Wild Turkey. The AUSTRALIAN JUNGLE FOWLS (Megapodinæ). The TALLEGALLI (Tallegalli). The BRUSH TURKEYS (Catheturus):—The Brush Turkey, or Wattled Tallegallus—The Maleo—The Ocellated Leipoa. The MEGAPODES (Megapodii):—The Australian Megapode 256–275

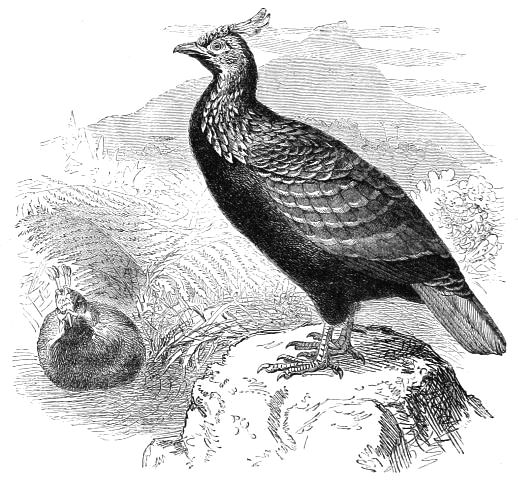

THE CURASSOWS, or HOCCOS (Cracidæ). The TRUE CURASSOWS, or HOCCOS (Craces):—The Common or Crested Curassow—The Wattled Curassow—The Red Curassow—The Galeated Curassow—The Mountain Curassow, or Lord Derby's Guan. The GUANS (Penelopæ):—The Supercilious Guan—The Pigmy, or Piping Guan—The Aracuan—The Hoactzin, or Stink Bird. The TINAMOUS (Crypturidæ):—The Tataupa—The Inambu 275–285

THE AMERICAN QUAILS (Nothura):—The Lesser Mexican Quail—The Macuca. The SPUR-FOWLS (Galloperdices):—The Painted Spur-fowl 285–286

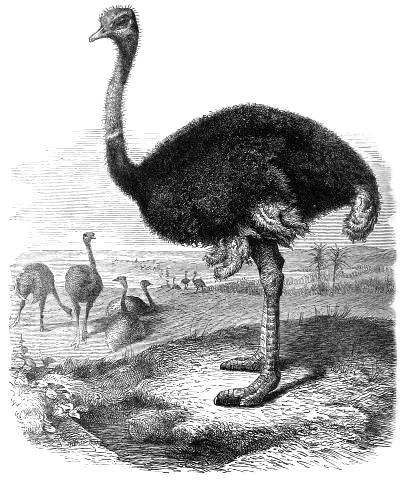

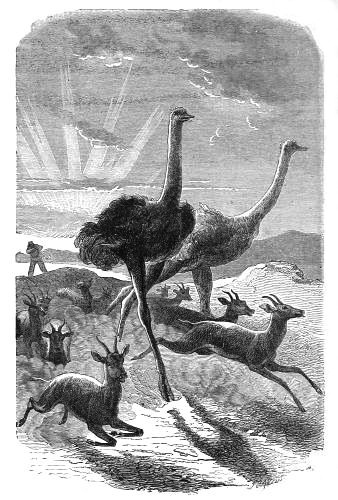

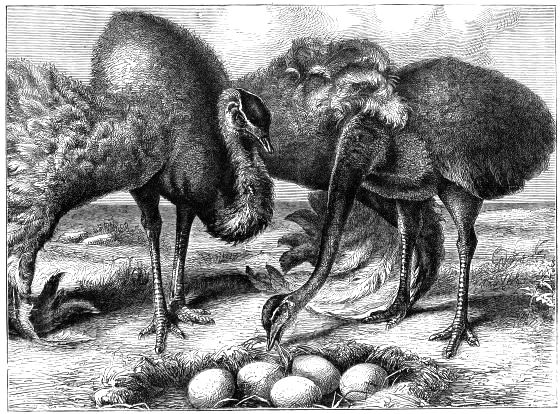

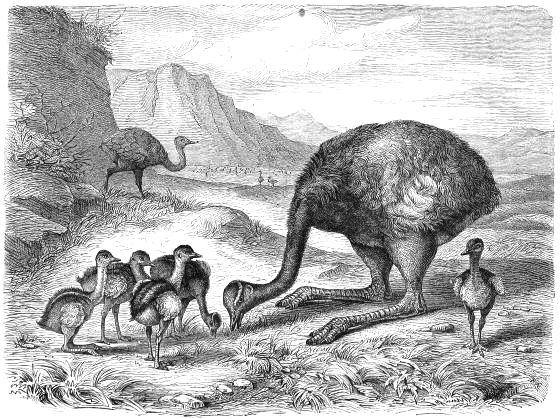

THE OSTRICH (Struthio camelus). The NANDUS (Rhea):—The Nandu, or American Ostrich—The Long-billed Nandu—The Dwarf Nandu 287–299

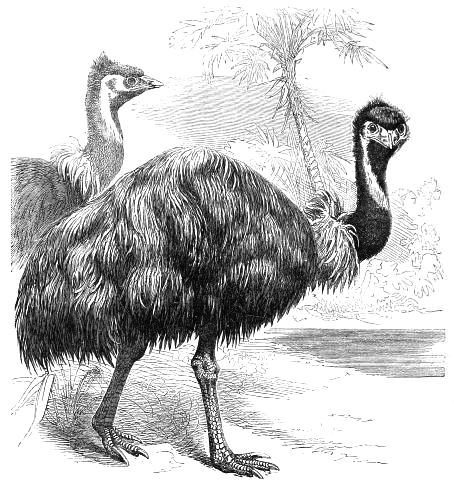

THE EMUS (Dromæus):—The Emu—The Spotted Emu 300–302

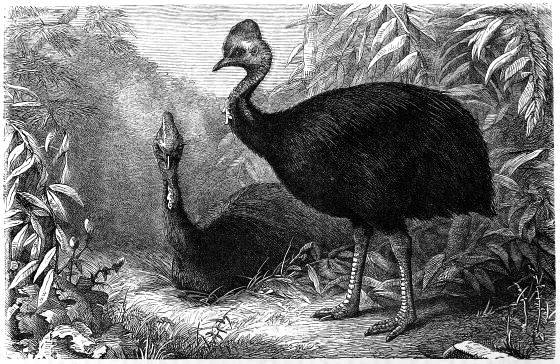

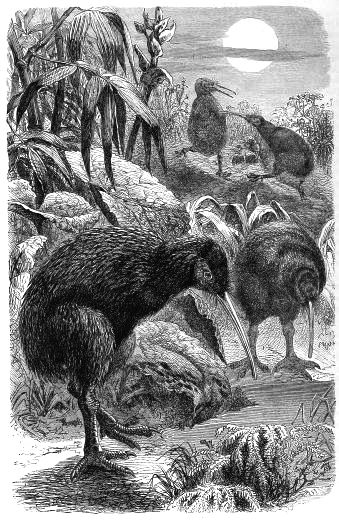

THE CASSOWARIES (Casuarii):—The Helmeted Cassowary—The Mooruk—The Australian Cassowary. The KIVIS (Apteryges):—The Kivi-Kivi—Mantell's Apteryx—Owen's Apteryx 302–312

——♦——

| PLATE | XXI.—THE BLUE GRANDALA. |

| " | XXII.—THE WHISKERED FANTAIL. |

| " | XXIII.—THE CRIMSON TOPAZ. |

| " | XXIV.—THE EUROPEAN BEE-EATER. |

| " | XXV.—THE BEAUTIFUL TROGON. |

| " | XXVI.—THE TOUCAN. |

| " | XXVII.—THE ROCK PIGEON. |

| " | XXVIII.—THE PTARMIGAN. |

| " | XXIX.—THE SANGUINE FRANCOLIN. |

| " | XXX.—THE HASTINGS TRAGOPAN. |

| FIG. | PAGE | |

| 1. | The Sai, or Blue Caereba (Cæreba cyanea) | 3 |

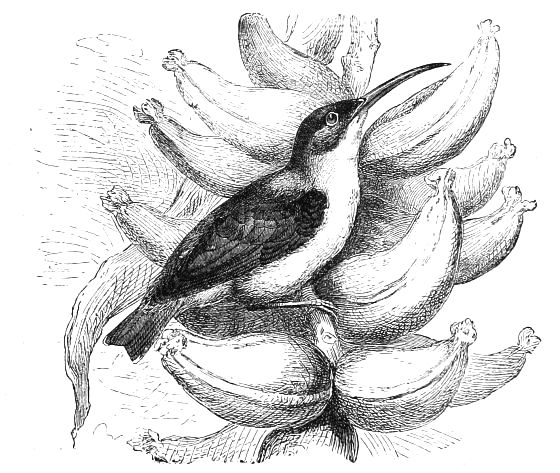

| 2. | The Banana Quit (Certhiola flaveola) | 4 |

| 3. | The Abu-Risch (Hedydipna metallica) | 5 |

| 4. | The Hanging Bird (Arachnocestra longirostris) | 9 |

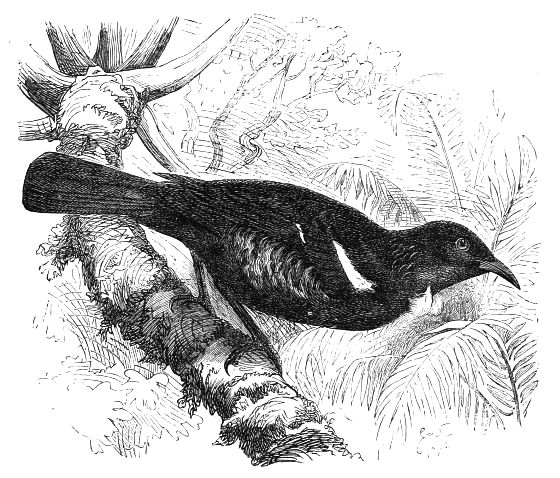

| 5. | The Poe, or Tui (Prosthemadera circinata) | 13 |

| 6. | The Hoopoe (Upupa epops) | 16 |

| 7. | The Red Oven Bird (Furnarius rufus) | 17 |

| 8. | The Hairy-cheeked Stair-beak (Xenops genibarbis) | 20 |

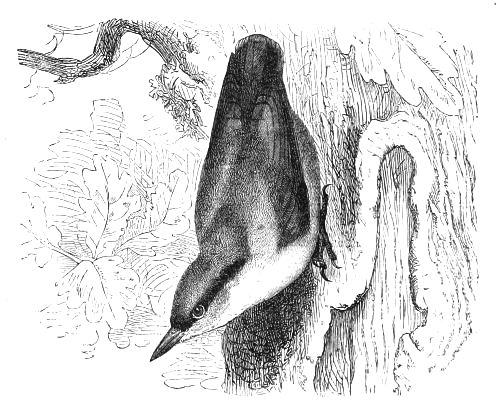

| 9. | The Common Nuthatch (Sitta cæsia) | 21 |

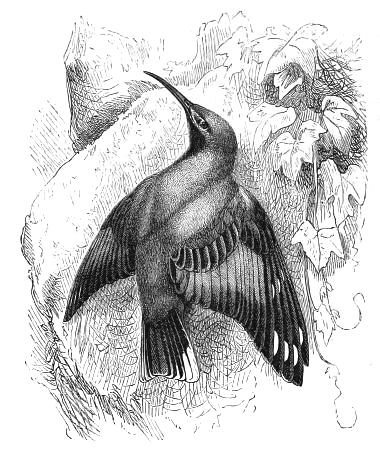

| 10. | The Alpine Wall-creeper (Tichodroma muraria) | 24 |

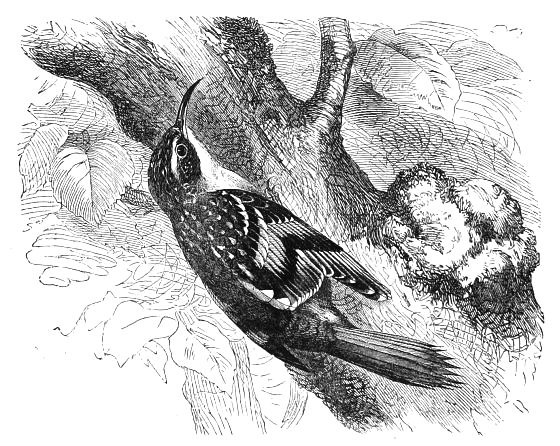

| 11. | The Common Tree-creeper (Certhia familiaris) | 25 |

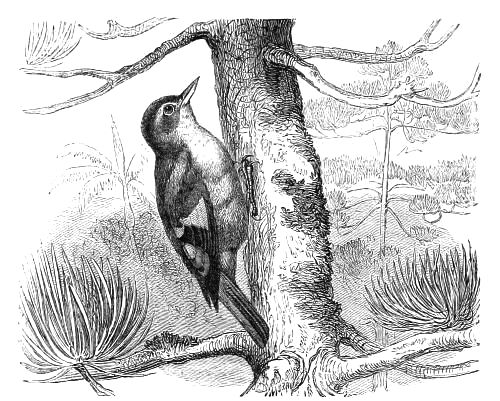

| 12. | The Woodpecker Tree-chopper, (Dendraplex picus) | 28 |

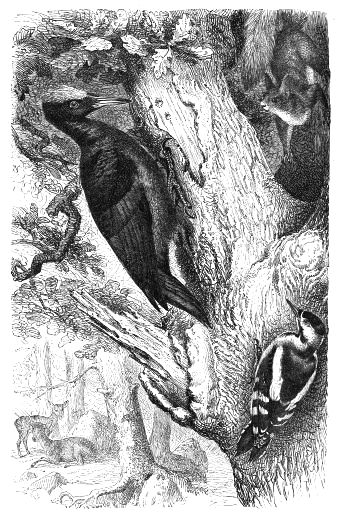

| 13. | The European Black Woodpecker (Dryocopus martius) | 29 |

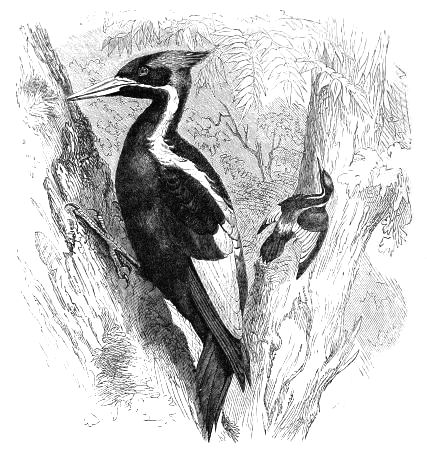

| 14. | The Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) | 32 |

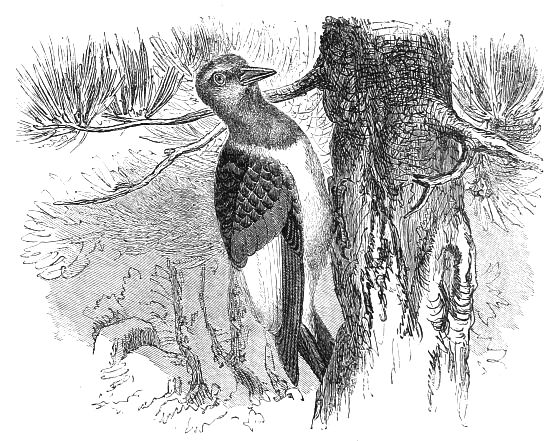

| 15. | The Red-headed Black Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) | 33 |

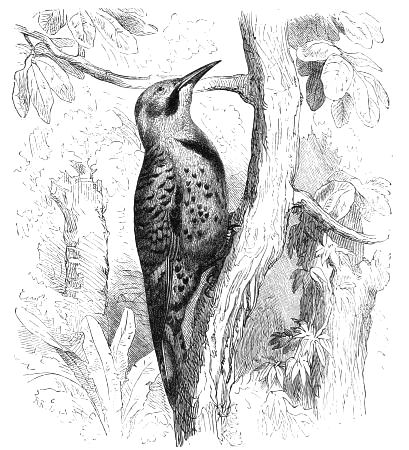

| 16. | The Green Woodpecker (Gecinus viridis) | 40 |

| 17. | The Golden-winged Woodpecker (Colaptes auratus) | 41 |

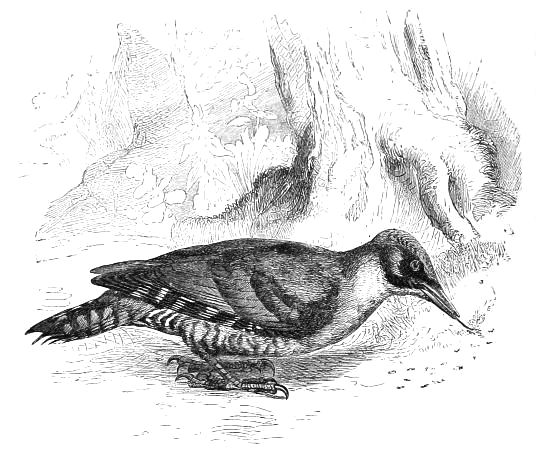

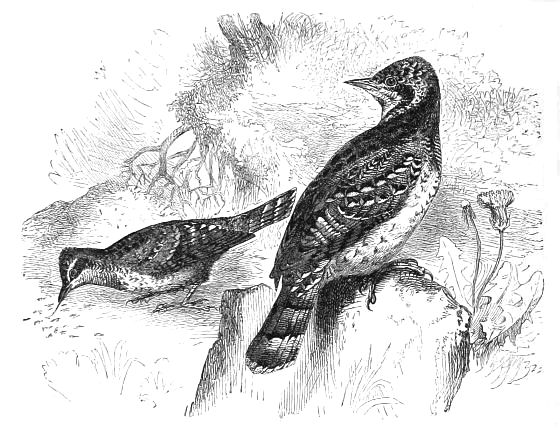

| 18. | The Wry-neck (Yunx torquilla) | 44 |

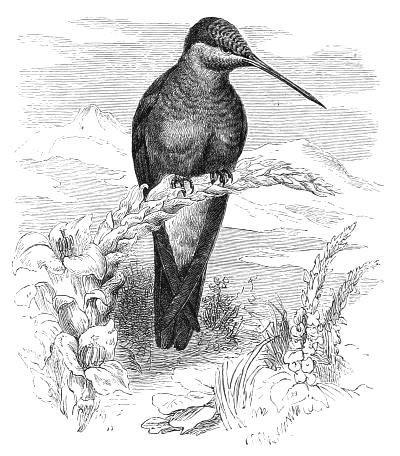

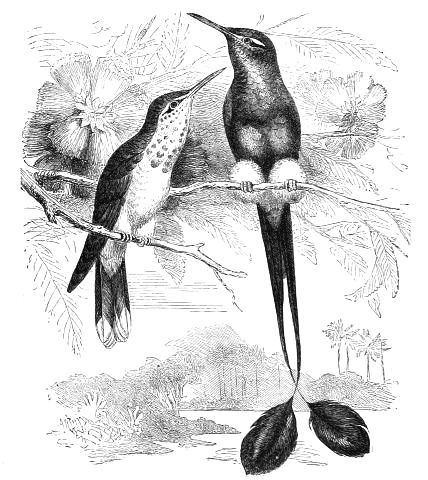

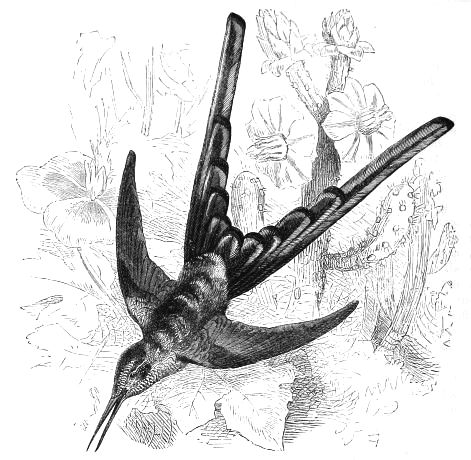

| 19. | The Giant Humming Bird (Patagona gigas) | 48 |

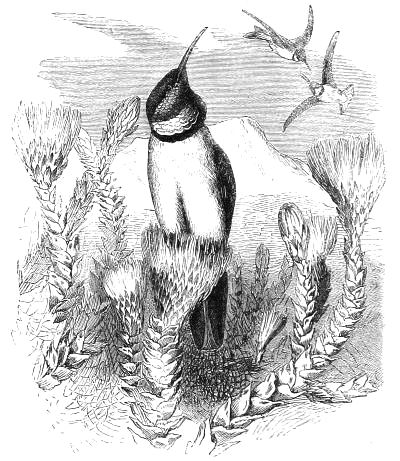

| 20. | The Sword-bill Humming Bird (Docimastes ensifer) | 49 |

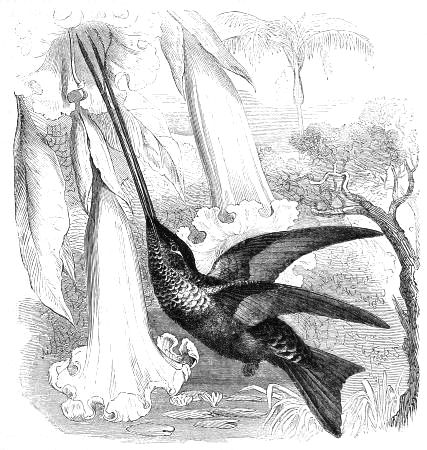

| 21. | The Sickle-billed Humming Bird (Eutoxeres aquila) | 52 |

| 22. | The Chimborazian Hill-star (Oreotrochilus Chimborazo) | 53 |

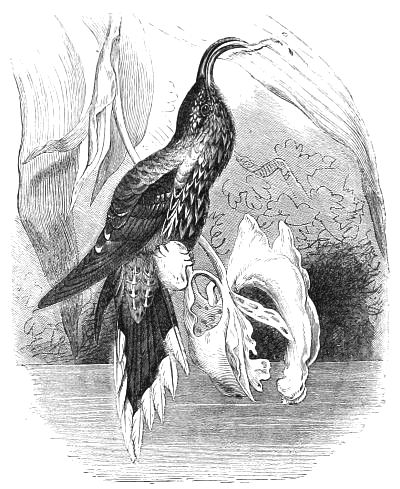

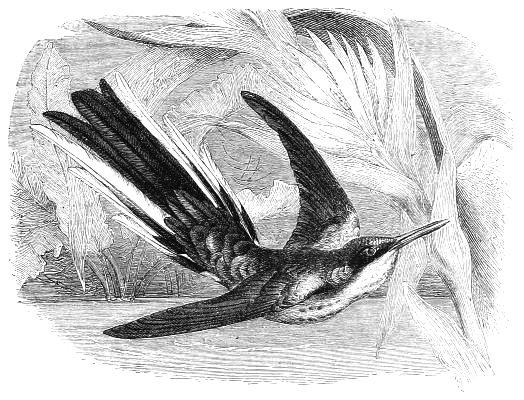

| 23. | The Crimson Topaz Humming Bird (Topaza pella) | 56 |

| 24. | The Brazilian Fairy (Heliothrix auriculata) | 61 |

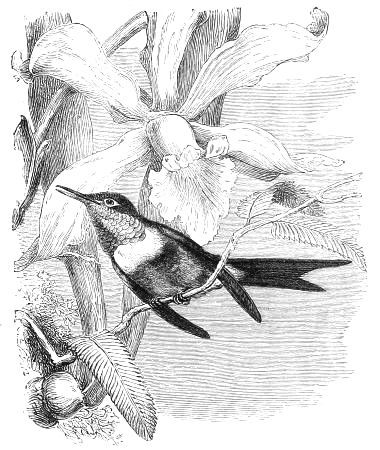

| 25. | The Amethyst Humming Bird (Calliphlox amethystina) | 65 |

| 26. | The Splendid Coquette (Lophornis ornata) | 67 |

| 27. | The Horned Sun-gem (Heliactinus cornutus) | 68 |

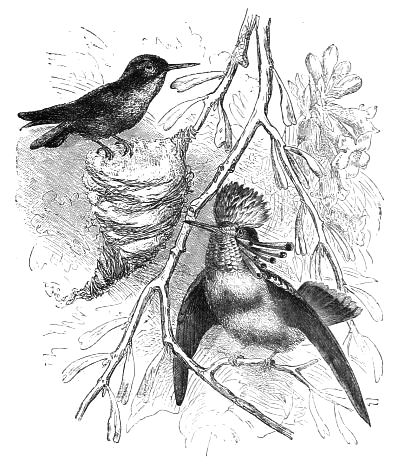

| 28. | The White-footed Racket-tail (Steganurus Underwoodii) | 69 |

| 29. | The Sappho Comet (Sparganura Sappho) | 72 |

| 30. | Humming Birds | 73 |

| 31. | The Bee-wolf (Melittotheres nubicus) | 77 |

| 32. | The Australian Bee-eater (Cosmäerops ornatus) | 80 |

| 33. | The Blue Roller (Coracias garrulus) | 81 |

| 34. | The Mot-mot (Prionites momota) | 84 |

| 35. | The Java Broad-throat (Eurylaimus Javanicus) | 85 |

| 36. | The European Kingfisher (Alcedo ispida) | 88 |

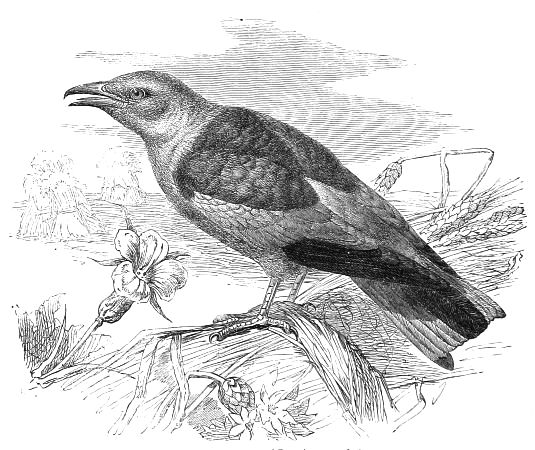

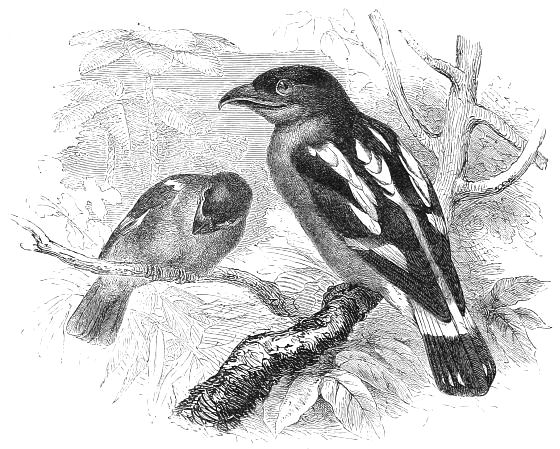

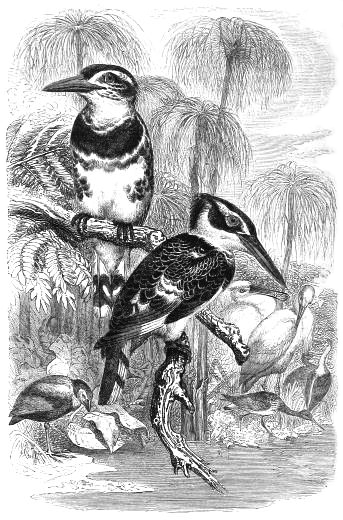

| 37. | Grey Kingfishers (Ceryle rudis) | 92 |

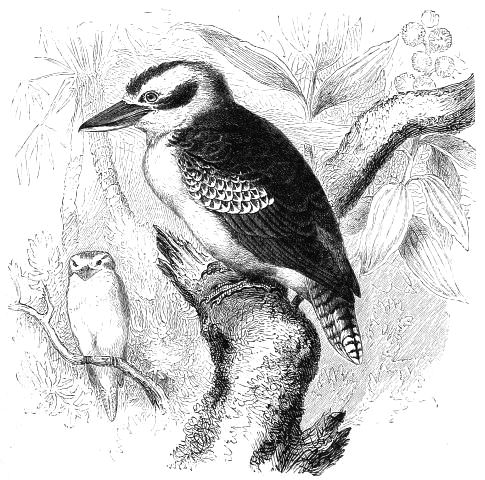

| 38. | The Laughing Jackass (Paralcyon gigas, or Dacelo gigantea) | 93 |

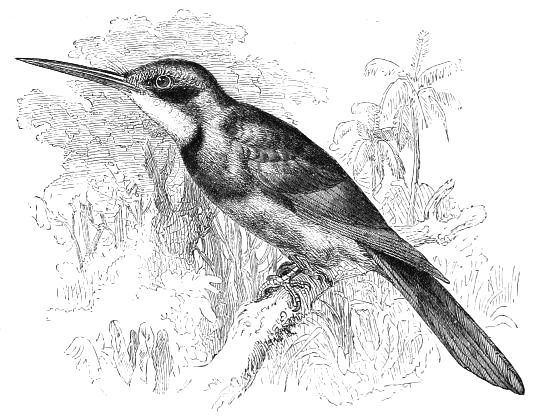

| 39. | The Green Jacamar (Galbula viridis) | 97 |

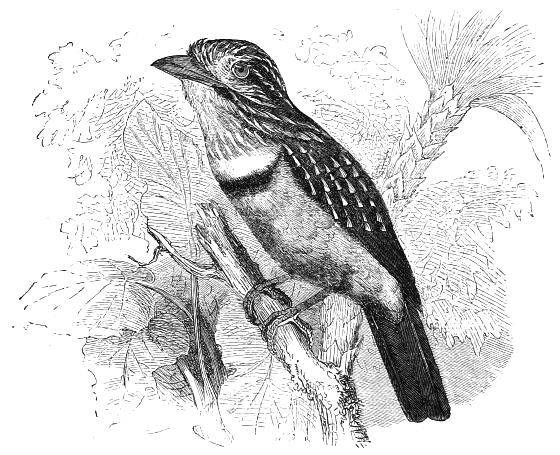

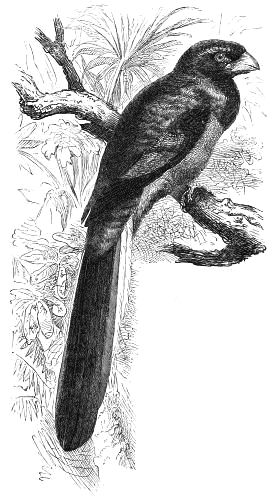

| 40. | The Dusky Trappist, or Bearded Cuckoo (Monasta fusca) | 99 |

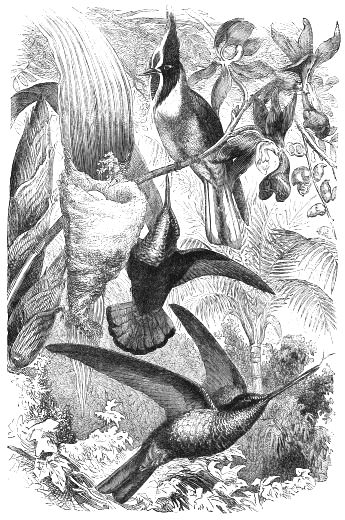

| 41. | The Narina (Hapaloderma narina) | 101 |

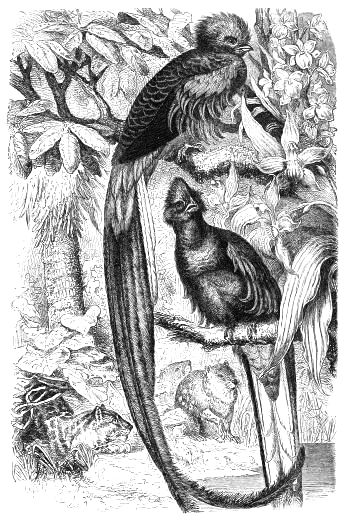

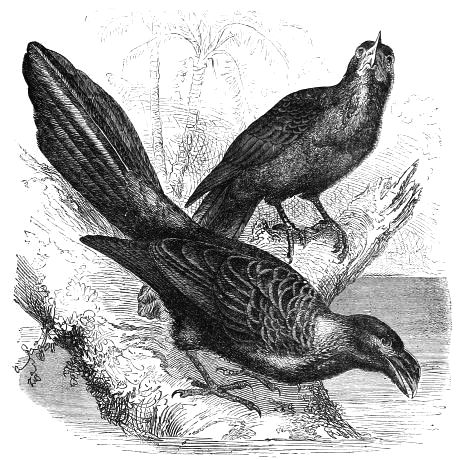

| 42. | Quesals, or Resplendent Trogons (Calurus paradiseus, or C. resplendens) | 104 |

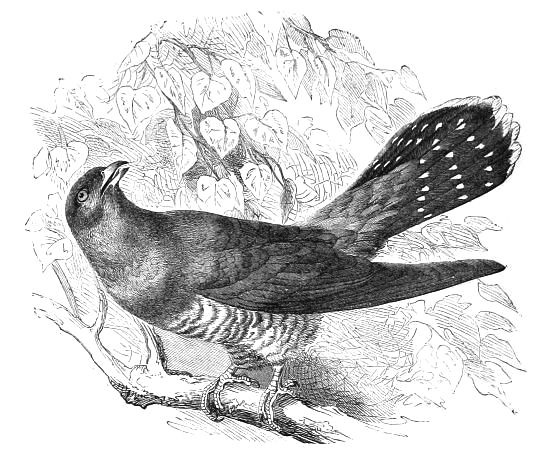

| 43. | The Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) | 108 |

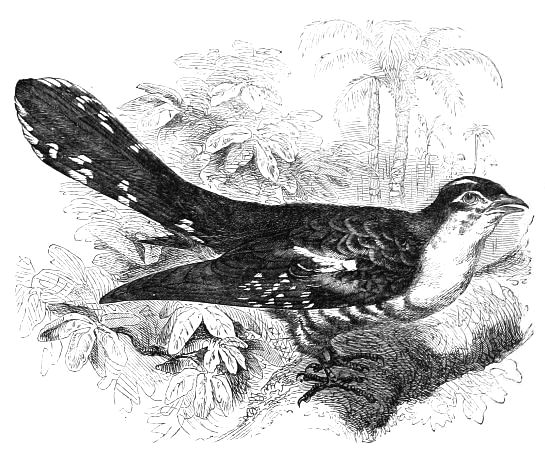

| 44. | The Jay Cuckoo (Coccystes glandarius) | 109[viii] |

| 45. | The Didrik, or Golden Cuckoo (Chrysococcyx auratus) | 112 |

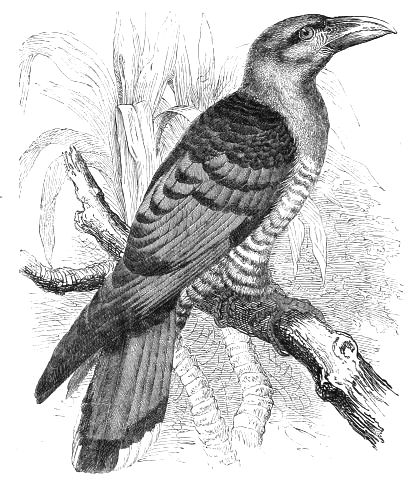

| 46. | The Giant Cuckoo, or Channel-bill (Scythrops Novæ-Hollandiæ) | 113 |

| 47. | The Kokil, or Large Green-billed Malkoha (Zanclostomus tristis) | 115 |

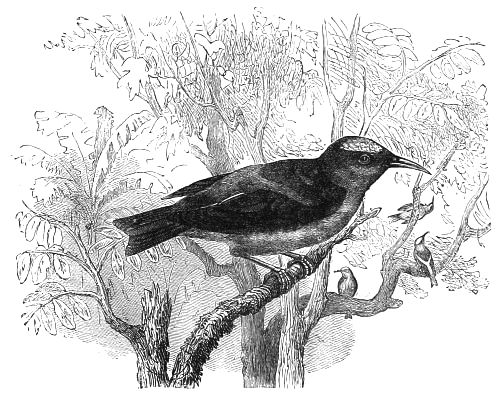

| 48. | The Ani, or Savanna Blackbird (Crotophaga ani) | 120 |

| 49. | The Wrinkled-beaked Tick-eater (Crotophaga rugirostris) | 121 |

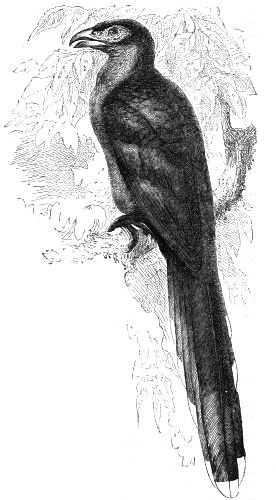

| 50. | The Pheasant Coucal (Polophilus phasianus) | 124 |

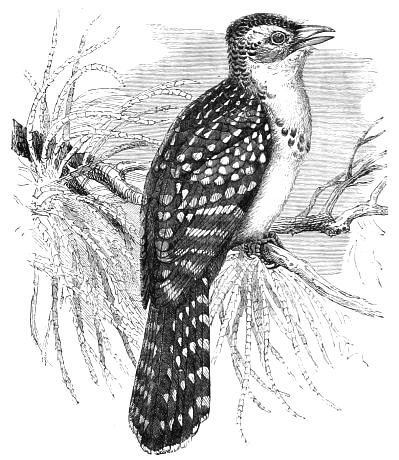

| 51. | The Pearl Bird (Trachyphonus margaritatus) | 125 |

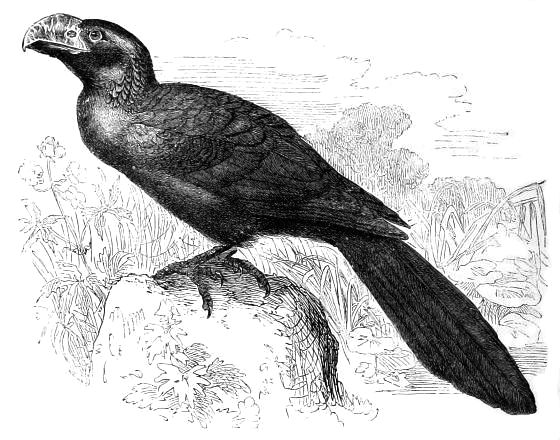

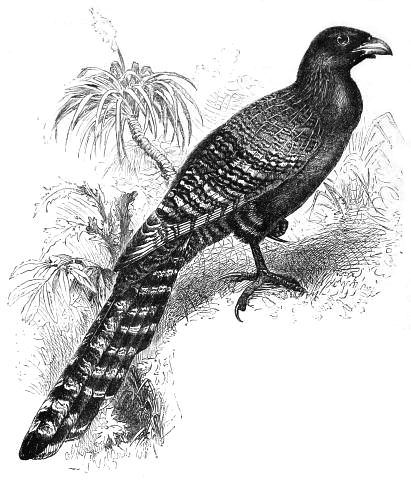

| 52. | The Arassari (Pteroglossus aracari) | 128 |

| 53. | The Toco Toucan (Ramphastus toco) | 129 |

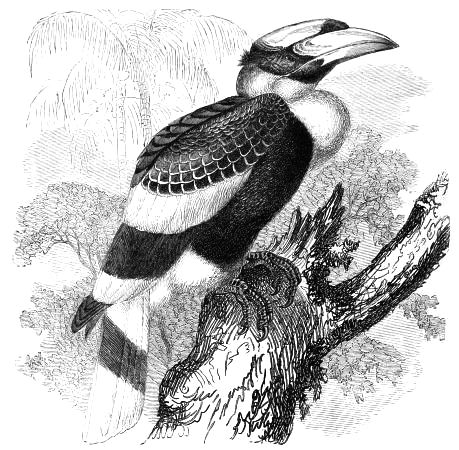

| 54. | The Tok (Rhynchaceros erythrorhynchus) | 133 |

| 55. | The Homray (Dichoceros bicornis) | 136 |

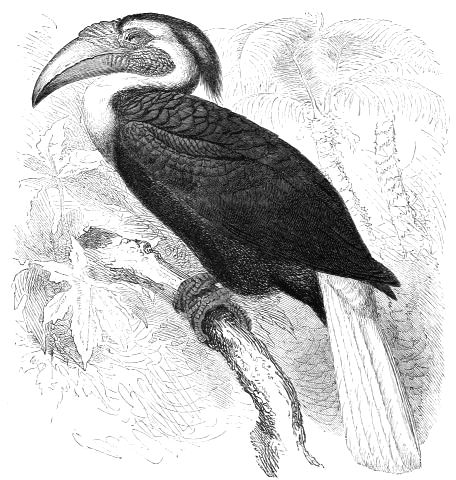

| 56. | The Djolan, or Year Bird (Rhyticeros plicatus) | 137 |

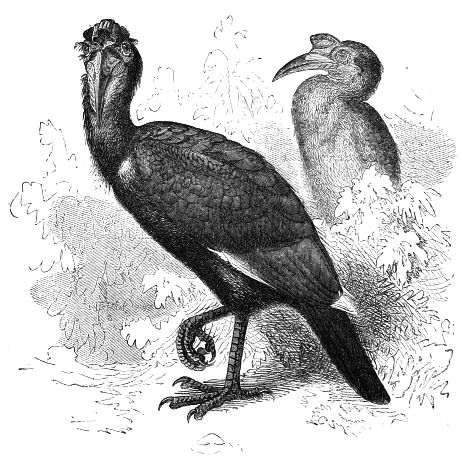

| 57. | The Abbagamba, or Abyssinian Hornbill (Bucorax Abyssinicus) | 139 |

| 58. | Nestlings of The Abbagamba | 140 |

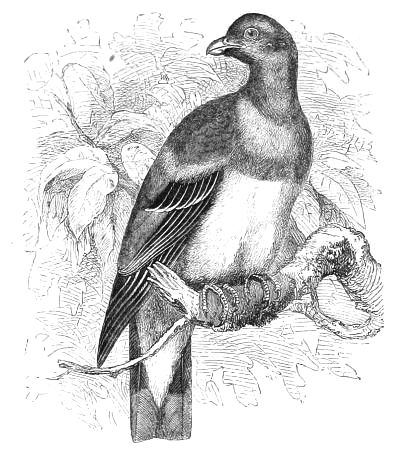

| 59. | The Parrot Pigeon (Phalacroteron Abyssinica) | 144 |

| 60. | The Ring-dove, or Wood Pigeon (Palumbus torquatus) | 145 |

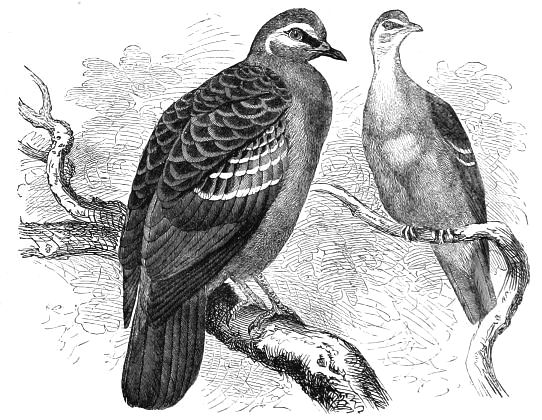

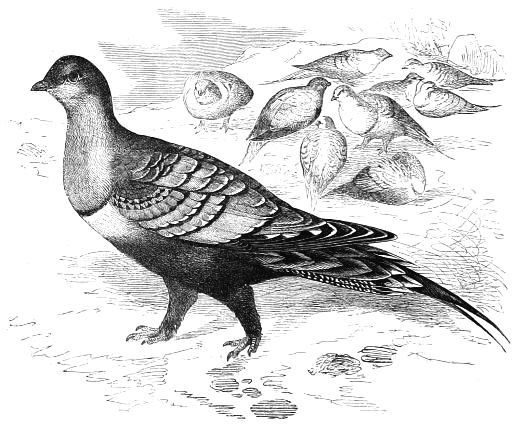

| 61. | The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) | 148 |

| 62. | Turtle Doves | 156 |

| 63. | Dwarf Pigeon (Chalcopeleia Afra) | 157 |

| 64. | The Kukuli (Melopeleia meloda) | 160 |

| 161. | The Striped Sparrow-hawk Pigeon (Geopeleia striata) | 161 |

| 66. | The Crested Bronze-wing (Ocyphaps lophotes) | 164 |

| 67. | The Bronze-winged Pigeon (Phaps chalcoptera) | 165 |

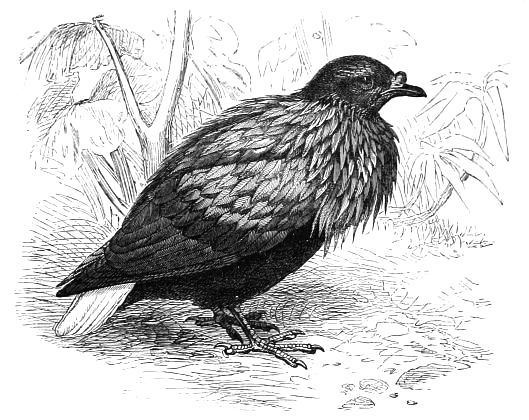

| 68. | The Hackled Ground Pigeon (Callœnas Nicobarica) | 168 |

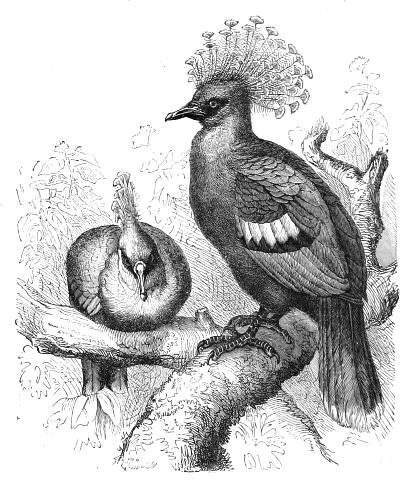

| 69. | The Victoria Crowned Pigeon (Goura Victoria) | 169 |

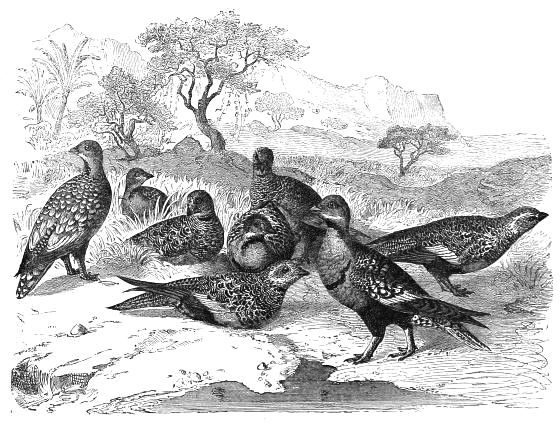

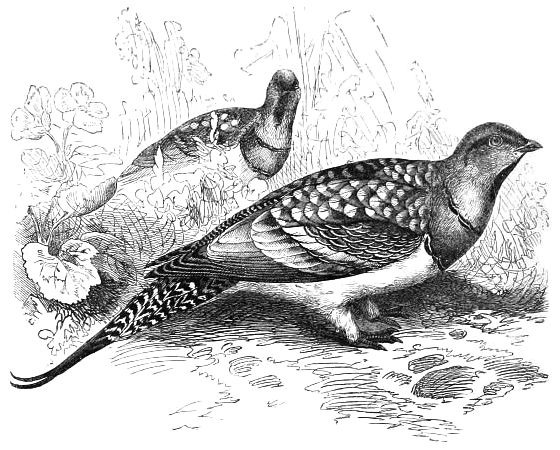

| 70. | Sand Grouse | 173 |

| 71. | The Khata (Pterocles alchata) | 176 |

| 72. | The Common Sand Grouse (Pterocles exustus) | 177 |

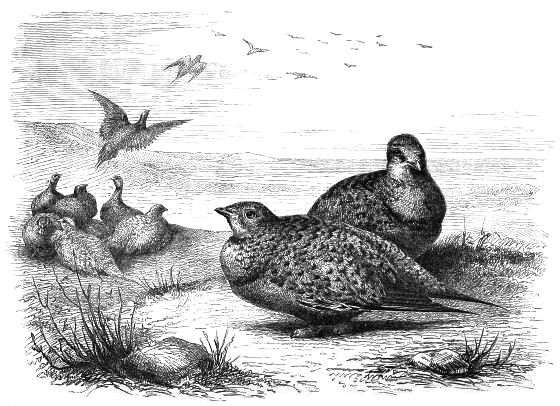

| 73. | Pallas's Sand Grouse, or Sand Grouse of The Steppes | 180 |

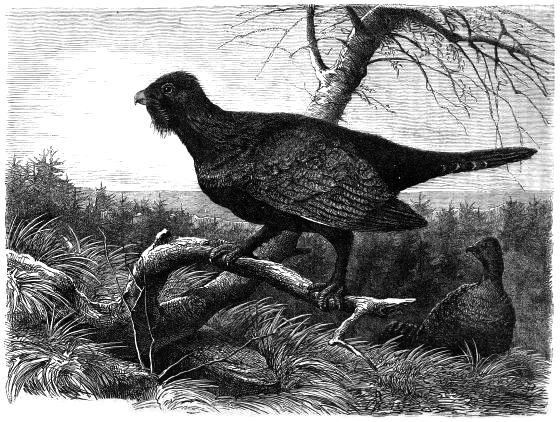

| 74. | The Capercali (Tetrao urogallus) | 184 |

| 75. | The Black Cock (Lyrurus tetrix) | 185 |

| 76. | Hybrid Grouse (Tetrao medius) | 188 |

| 77. | Hazel Grouse (Bonasia sylvestris) | 189 |

| 78. | The Prairie Hen (Cupidonia Americana) | 192 |

| 79. | The Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopus albus) | 197 |

| 80. | The Alpine Ptarmigan (Lagopus Alpinus), in Summer plumage | 200 |

| 81. | The Alpine Ptarmigan (Lagopus Alpinus), in Winter plumage | 201 |

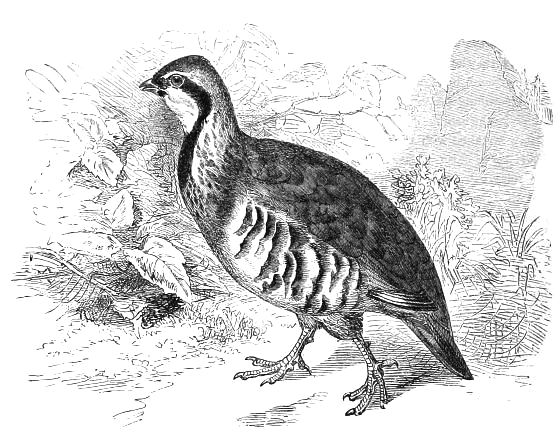

| 82. | The Red-legged Partridge (Caccabis rubra) | 208 |

| 83. | The Common Partridge (Perdix cinerea, or Starna cinerea) | 209 |

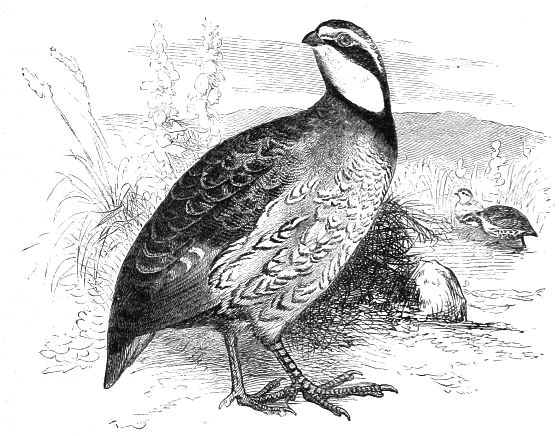

| 84. | The Virginian Partridge (Ortyx Virginianus) | 217 |

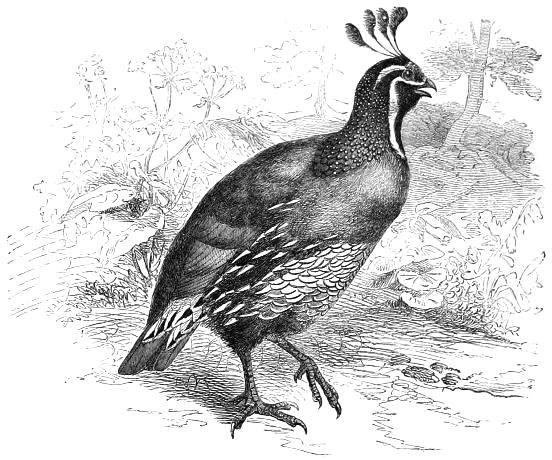

| 85. | The Californian Partridge (Lophortyx Californianus) | 220 |

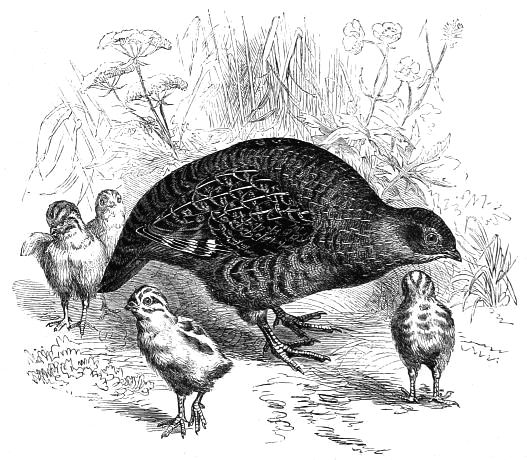

| 86. | The Common Quail (Coturnix communis) | 221 |

| 87. | The Chinese Quail (Excalfactoria Chinensis) | 224 |

| 88. | The African Bush Quail (Turnix Africanus, or T. Gibraltariensis) | 228 |

| 89. | The Monaul, or Impeyan Pheasant (Lophophorus resplendens, refulgens, or Impeyanus) | 229 |

| 90. | The Sikkim Horned Pheasant (Ceriornis Satyra) | 233 |

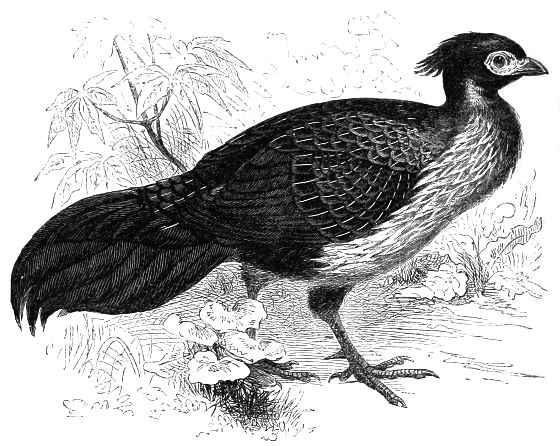

| 91. | The Kaleege, or Black Pheasant (Euplocamus-Gallophasis-melanotus) | 240 |

| 92. | The Silver Pheasant (Nycthemerus argentatus, or Euplocamus nycthemerus) | 241 |

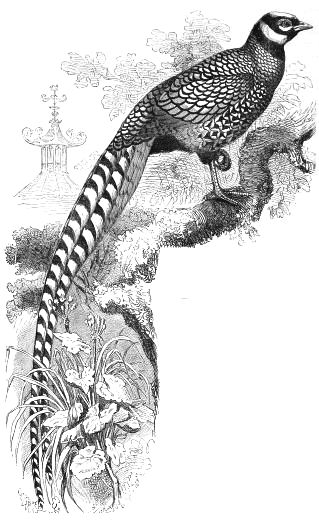

| 93. | Reeves' Pheasant (Phasianus Reevesii, or P. veneratus) | 244 |

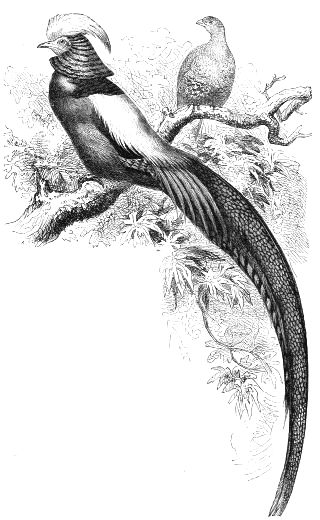

| 94. | The Golden Pheasant (Thaumalea picta) | 245 |

| 95. | The Chinese Eared Pheasant (Crossoptilon auritum) | 248 |

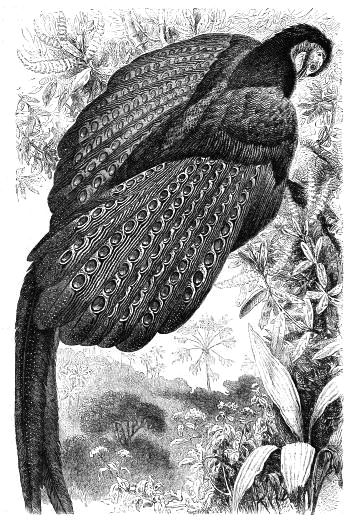

| 96. | The Argus Pheasant, or Kuau (Argus giganteus) | 249 |

| 97. | The Chinquis, or Assam Peacock Pheasant (Polyplectron chinquis) | 252 |

| 98. | The Common Guinea Fowl (Numida meleagris) | 257 |

| 99. | The Ocellated Turkey (Meleagris ocellata) | 260 |

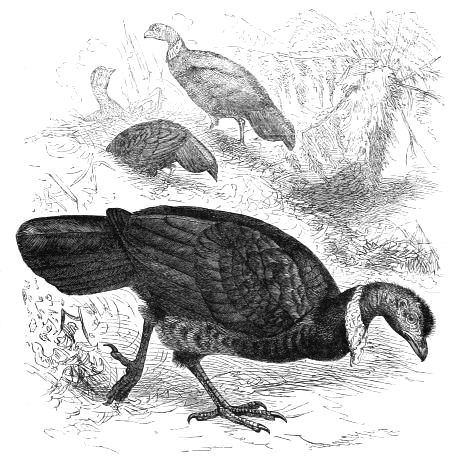

| 100. | The Brush Turkey (Catheturus Lathami) | 265 |

| 101. | The Maleo (Megacephalon Maleo) | 269 |

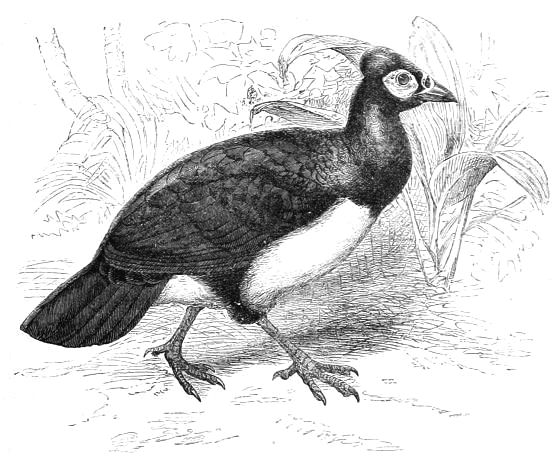

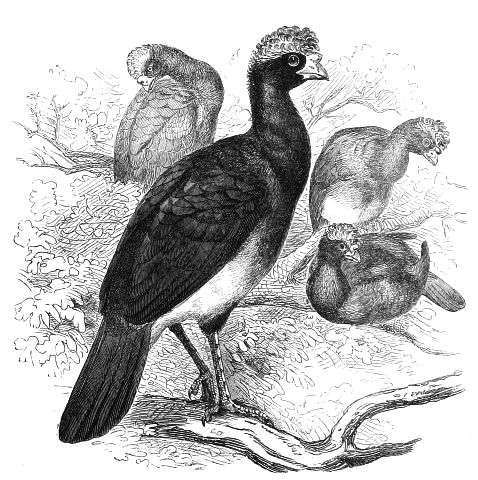

| 102. | The Crested Curassow (Crax alector) | 277 |

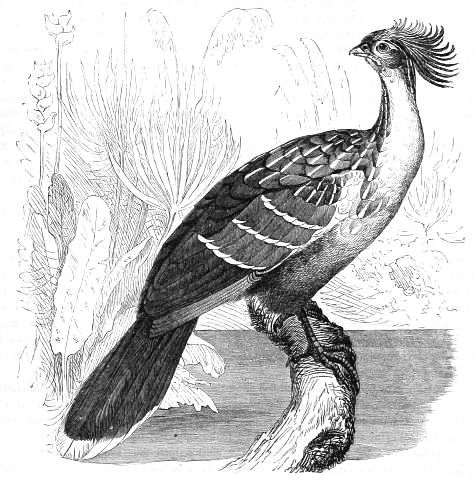

| 103. | The Hoactzin, or Stink Bird (Opisthocomus cristatus) | 281 |

| 104. | The Inambu (Rhynchotus rufescens) | 284 |

| 105. | The Ostrich (Struthio camelus) | 288 |

| 106. | An Ostrich Hunt | 292 |

| 107. | Nandus (Rhea Americana), with Nest and Eggs | 293 |

| 108. | The Nandu, or American Ostrich (Rhea Americana) | 297 |

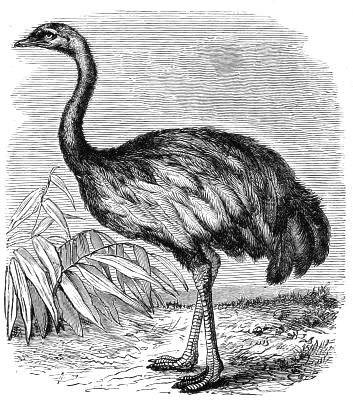

| 109. | The Emu (Dromæus Novæ-Hollandiæ) | 300 |

| 110. | Cassowary (Casuarius galeatus) | 304 |

| 111. | The Kivi-Kivi (Apteryx Australis) | 308 |

| 112. | The Nandu, or Rhea | 312 |

—♦—

The families which, according to natural arrangement, seem to constitute a third division of the great class of birds are principally characterised by the conditions under which they procure their food, viz., by searching for it in situations where it can only be obtained by diligent investigation or laborious exertion. Their diet is usually of a very mixed description, consisting partly of insects and partly of materials derived from the vegetable creation. Many of them were at one time considered to subsist entirely upon the honeyed juices of the fruits and blossoms, among which they spend the greater part of their lives; and, although it is now generally admitted that the insects which abound in the nectared chalices whence they draw their supplies constitute a principal article of their nutriment, they are not the less on that account to be regarded as riflers of the saccharine stores laid up for their use in many a beautiful cup temptingly held forth for their enjoyment. Such are the Honeysuckers and the gorgeously decorated Humming Birds, whose sumptuous garb would seem literally intended to "gild refined gold and paint the lily." A second important group, constituted likewise for the purpose of preying upon insects, has been specially adapted to climb the trunks of trees in search of the innumerable hosts of destroyers that lurk beneath the bark, or in the crevices of wood in progress of decay. These constitute an extensive family, well exemplified by the Woodpeckers; while others, furnished with beaks and feet of very diverse structure, search everywhere for the particular kind of nourishment upon which they are destined to subsist.

The name we have selected for this extensive division of the feathered creation was first employed by Reichenbach, although not exactly in the same sense as that in which we are going to apply the term, neither can we hit upon any single character whereby all the species included under this denomination can be easily designated; nevertheless, however they may differ among themselves, there is a certain conformity in their structure, and a general resemblance in their habits, which will probably be appreciated when we have put the reader in possession of the details contained in the following pages.

We shall, therefore, at once commence their history, by describing them under the following headings.

The CLIMBING BIRDS (Scansor) are for the most part recognisable by their slender though powerful body, short neck, and large head. The long or medium-sized beak is either strong and[2] conical, or weak and of a curved form; the feet are short, and the long toes either arranged in pairs or placed together in the usual manner, and armed with long, hooked, and sharp claws. The moderate-sized wing, which is usually rounded at its extremity, and occasionally of great breadth, is never slender or pointed; the formation of the tail is very various. Anything like a general description of the plumage possessed by the different groups of this order would be impossible; some, glittering with gay and even resplendent colours, dart through the air like living gems, whilst others are clad in such dull and sombre livery as to be scarcely distinguishable from the earth or trees upon which they are formed to live. The various representatives of the Scansor may be said to occupy almost every region of our earth; some groups are migratory, and leave their native lands annually with the utmost regularity, whilst others remain throughout the entire year within a certain limited district. Woods and forests are the localities principally occupied by these birds, though they are by no means incapable of ascending rocks, or seeking for their food upon the ground, over the surface of which they run with considerable facility. Their flight is good, but it is upon the trees alone that the Scansor exhibit the full beauty and ease of their movements. All the members of this order consume insects, and many devour fruit, berries, seeds, honey, and the pollen of plants. As regards their powers of song they are by no means gifted; indeed, the most highly endowed amongst them rarely rise above the utterance of a few pleasing notes during the breeding season. The construction of the nests of the Scansor varies so considerably that we shall confine ourselves to speaking of them in their appropriate places.

It is usual among systematic writers to associate many of the birds which we have included in the present order as slender-billed forms of one or other of the preceding divisions, more especially those usually denominated TENUIROSTRES, and perhaps we shall be harshly judged for our departure from the usual custom; be that as it may, the resemblance between some of the Climbing Birds and some Singing Birds is undeniable, and it is upon that ground that we treat of them in this place.

The TENUIROSTRAL species are distinguishable from all others by the slenderness of their beak, which is usually more or less curved, and by the feebleness of their feet, the toes of which are not arranged in pairs. They may be grouped as follows:—

The FLOWER BIRDS (Certhiola) constitute a small group of South American species, remarkable for the great beauty of their plumage. All possess a slender body, moderate-sized wing, containing nine primaries (of which the second, third, and fourth are the longest), and a somewhat soft-feathered tail, of medium length. The beak is also of moderate size, much arched at its base, and curved slightly inwards at its margins. The tongue is long, divided, and thread-like at its tip, but not protrusible; the foot is short and powerful. The sexes are readily distinguishable by the diversity of their coloration, the plumage of the male being blue, and that of the female usually green. All the members of this group closely resemble our singing birds in their habits and mode of life; they subsist upon insects, seeds, corn, and berries, in pursuit of which they hop from branch to branch, with ever restless activity. According to the Prince von Wied, they regard fruit of various kinds, particularly oranges, with especial favour, and, when these are ripe, constantly venture into the gardens, even close to dwelling-houses, with all the fearlessness of the Domestic Sparrow; at other seasons they prefer to keep within the shelter of well-wooded thickets. Their song, we believe, consists of but a single note.

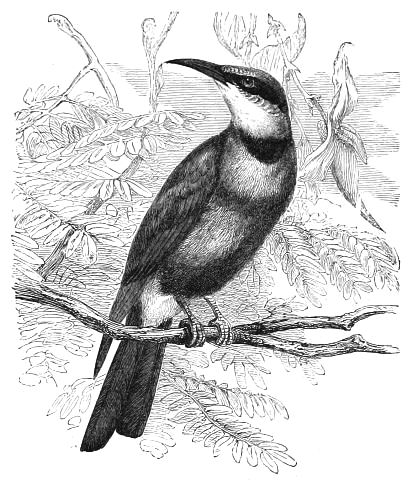

The BLUE BIRDS (Cæreba) are at once recognisable by their long, thin beak, which is compressed at its sides, and slightly notched near its very sharp tip; the wing is long and pointed, its[3] second and third quills, which are of equal size, exceeding the rest in length. The moderate-sized tail is straight at its extremity; the legs are weak, and the tongue, which is tolerably long, composed of two lobes, terminating in fringed margins.

THE SAI, OR BLUE CAEREBA.

The SAI, or BLUE CAEREBA (Cæreba cyanea). The prevailing colour of this beautiful species is a brilliant light blue, shading towards the top of the head into resplendent blueish green; the upper part of the back, wings, and tail, as well as a stripe surrounding the eye, are black, and the inner margins of the wings yellow. The eye is greyish brown, the beak and foot bright orange-red. The plumage of the female is siskin-green on the upper parts of the body, and pale green beneath; the throat is whitish. The length of this species is four inches and two-thirds, the wing measures two inches and a quarter, and the tail one inch and a quarter.

THE SAI, OR BLUE CAEREBA (Cæreba cyanea).

These beautiful birds are met with throughout the greater part of South America, and are especially numerous about Espirito Santo. The Prince von Wied found them in large numbers inhabiting the forests near the coast, and tells us, that except during the breeding season, they live in small parties of six or eight, which disport themselves among the topmost branches of the trees, frequently associating with Tangaras, and such other of the feathered inhabitants of their leafy retreats as are about their own size. Fruit, seeds, and insects constitute their principal means of subsistence, and in pursuit of these they display an agility and dexterity fully equalling that of our own Titmouse. The voice of the Sai is only capable of producing a gentle twitter. Schomburghk mentions that large numbers of a very similar species are destroyed by the natives, who employ the gay and glossy feathers as personal ornaments.

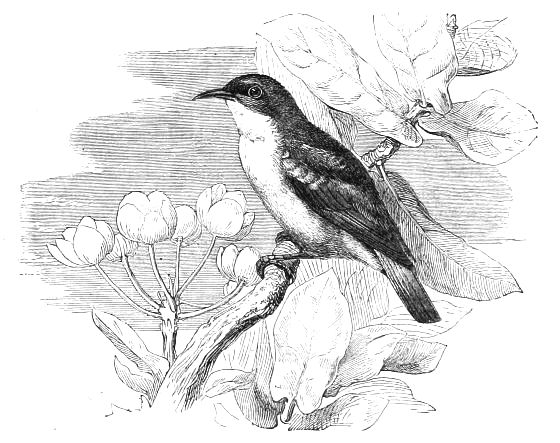

The PITPITS (Certhiola) have a high slender beak, which curves gently towards its sharp tip; their wings are long, their tail short, and their tongue divided into two parts, each of which terminates in a brush of thread-like fibres.

THE BANANA QUIT, OR BLACK AND YELLOW CREEPER.

The BANANA QUIT, or BLACK AND YELLOW CREEPER (Certhiola flaveola), is blackish brown on the upper parts of the body, and of a beautiful bright yellow on the under side and rump; a line that passes above the eyes, the anterior borders of the primary quills, the tips of the tail, and its two outer feathers are white; the throat is ash-grey, the eye greyish brown, the back is black, and the foot brown. The female is blackish olive on the back, and pale yellow on the under side; in other respects her plumage resembles that of her mate. The length of this species is three inches and five-sixths; the wing measures two inches and one-sixth, and the tail one inch.

THE BANANA QUIT (Certhiola flaveola).

"Scarcely larger than the average size of Humming Birds," writes Mr. Gosse, "this little Creeper is often seen in company with them, probing the same flowers, and for the same purpose, but in a very different manner. Instead of hovering in front of each blossom, a task to which his short wings would be utterly incompetent, the Quit alights on the tree, and proceeds in most business-like manner to peep into the flowers, hopping actively from twig to twig, and throwing his body into all positions, often clinging by his feet with his head downwards, the better to reach the blossoms with his curved beak and pencilled tongue; the minute insects which are concealed in the flowers are always the objects of his search. Unsuspectingly familiar, these birds resort much to the blossoming shrubs of enclosed gardens. The soft, sibilant note of the Quit is often uttered while the bird peeps about for food. The nest is frequently built in those low trees and bushes from whose twigs depend the[5] paper nests of the brown wasps, and in close contiguity with them. On the 4th of May, as I was riding to Savannah-le-Mar, I observed a Banana Quit with a bit of silk cotton in her beak, and, on searching, found a nest just commenced in a sage bush (Lautana camara). The structure, though incomplete, was evidently about to be a dome, and so far was entirely constructed of silk-cotton. A nest now before me is in the form of a globe, with a small opening in the side. The walls are very thick, composed of dry grass, intermixed irregularly with the down of Asclepias. This nest I found between the twigs of a branch of Bauhinia that projected over the high road, near Content, in St. Elizabeth's. The two eggs were greenish white, thickly but indefinitely dashed with red at the broad end."

THE ABU-RISCH (Hedydipna metallica).

In the Eastern Hemisphere the Flower Birds are represented by—

The HONEYSUCKERS (Nectarinia). These are small and delicately-constructed birds, adorned with plumage of the most brilliant hues; their body is compact, their beak thin, slightly curved, and sharply pointed. The moderately long wing contains ten primary quills. The formation of the tail is very varied, being either straight, rounded, or wedge-shaped at its extremity; its two centre feathers occasionally extend considerably beyond the rest. The tongue is long, very protrusible, and divided at its tip; the feet are high, and the toes slender. The coloration of the plumage varies not only in the two sexes, but also at different seasons; the feathers are moulted twice in the year, and only exhibit their gay tints during the period of incubation; towards the end of the season the males are clad in the same sombre hues that belong to the females and young. The Honeysuckers inhabit the whole of Africa, Asia, and Oceania, the first-mentioned continent being especially rich in species. Everywhere their glowing colours entitle them to be regarded as the[6] most striking ornaments of the woods, groves, or gardens they inhabit, whilst their intelligence renders the study of their habits extremely interesting. During the greatest part of the year they live in pairs, which occasionally associate into small parties during the breeding season. The nests of the Honeysuckers are constructed with great skill, and are usually suspended from thin branches or twigs. The eggs, which are few in number, are of a pure white.

THE ABU-RISCH.

The ABU-RISCH (Hedydipna metallica) represents a group recognisable by their slightly-curved beak, scarcely equalling the head in length; their comparatively short wings, in which the second, third, fourth, and fifth quills are of equal length; and their wedge-shaped tail, the two centre feathers of which are usually considerably prolonged. The male is of a metallic green on the head, throat, back, and shoulder-covers; the under side is bright yellow, a line upon the breast and the rump have a violet sheen; the quills and tail-feathers are blackish blue, the eye brown, and the beak and feet black. The back of the female is of a light olive-brown, and her under side sulphur-yellow; her quills and tail-feathers have light edges. The young resemble the mother, but are of a paler hue. The length of this species is six inches, of which three and a half belong to the centre tail-feathers, the rest do not exceed thirteen and a quarter; the wings measure two inches and one-sixth. The Abu-Risch is met with in all such parts of Africa as afford it the shelter of its favourite mimosa-trees, upon and around which it may literally be said to spend its whole existence. Early in the morning, and towards the close of the day, it usually perches quietly among the branches, and only displays its full vivacity during the noontide heat, when it flutters rapidly from blossom to blossom, in search of food, singing and chirping briskly as it flies in cheerful companionship with its almost inseparable mate. The song of the male is pleasing, and accompanied by a great variety of gesticulations and attitudes, calculated to exhibit his crest and plumage in all their varied beauty to the admiring gaze of the female, who usually endeavours to imitate her partner, but, owing to the comparative dullness of her colours, with a far less imposing result. In Southern Nubia the breeding season commences in March or April. The nest, which is variously formed, is neatly and skilfully woven with cotton-wool and similar materials, and lined with hair or spiders' webs. This pretty little structure is usually suspended from the end of a branch, at no great height from the ground, and is entered by an aperture at the side, frequently so situated that the leaves of the branch overhang and shade the entrance hole. Both parents work busily in constructing this snug apartment for their young, and have seldom completed their labours in less than a fortnight's time. The eggs, which are oval in shape, and white, are incubated by the female alone.

The FIRE HONEYSUCKERS (Æthopyga), the Indian representatives of the above group, are recognisable by the comparative thinness of their short but distinctly curved beak. In their wings the fourth quill exceeds the rest in length; the tail is wedge-shaped at its sides, and furnished with two long and slender feathers in its centre. The plumage of the male is enlivened by brightly-tinted stripes on the cheeks, while that of the female is sombre, and almost of uniform tint.

THE CADET.

The CADET (Æthopyga miles), one of the most beautiful members of this family, is blood-red on the back; the throat and upper part of the breast are of a somewhat paler crimson; the top of the head is violet, with a bright, metallic, green lustre. The nape is deep olive-yellow, and the belly pale greenish yellow; a steel-blue line, that becomes gradually broader, passes from the corners of the mouth to the sides of the neck; the quills are brown, edged with olive; the two centre tail-feathers[7] are glossy violet-green, and those of the exterior brown, with a purple sheen on the outer web. The eye is dark brown, the upper mandible black, the lower one brown, and the foot greyish black. The female is olive-green on the back, and yellowish green on the under side. The wing measures two inches and three-eighths, and the tail three inches.

The Cadet inhabits the northern and eastern parts of India, and is often met with in the Himalayas at an altitude of 2,500 feet above the level of the sea.

The BENT-BEAKS (Cyrtostomus) are distinguishable by their very decidedly curved beak, which equals the head in length, is blunt at its margins, and slightly incised towards its very sharp tip; the tarsus is comparatively high, the tail short and rounded, and the wings, in which the fourth and fifth quills are the longest, of moderate size. The plumage is of an olive-green on the upper parts of the body, and brightly coloured in the region of the throat.

THE AUSTRALIAN BLOSSOM RIFLER.

The AUSTRALIAN BLOSSOM RIFLER (Cyrtostomus Australis) is olive-green on the back, and of a beautiful bright yellow on the under side; the throat and upper breast are steel-blue. A short yellow streak passes over the eyes, and beneath this runs a long line of deeper shade; the eye is chestnut-brown, and the beak and feet black. The female is of an uniform yellow on the under side. According to Gould, the body of this species measures four inches and three-quarters, the wing two inches and one-eighth, and the tail two inches and a half.

"This pretty bird," says Macgillivray, as quoted by Gould, "appears to be distributed along the whole coast of Australia, the adjacent islands, and the whole of the islands in Jones's Straits. Although thus generally distributed, it is nowhere numerous, seldom more than a pair being seen together. Its habits resemble those of the Ptilotes, with which it often associates, but still more closely those of the Myzomela azura; like those birds, it resorts to the flowering trees, to feed upon the insects which frequent the blossoms, especially those of a species of Sciodophyllum. This singular tree, whose range on the north-eastern coast and that of the Australian Sun Bird appears to be the same, is furnished with enormous spike-like racemes of small scarlet flowers, which attract numbers of insects, and thus furnish an abundant supply of appropriate food. The Blossom Rifler is of a pugnacious disposition, as I have more than once seen; it drives away and pursues any visitor to the same tree. Perhaps this disposition is only exhibited during the breeding season. The nests we found at Cape York were pensile, and attached to the twig of a prickly bush; one, measuring seven inches in length, was of an elongated shape, with a rather large opening on one side, close to the top; it was composed of shreds of Melaleuca bark, a few leaves, various fibrous substances, rejectamenta of caterpillars, &c., and lined with the silky cotton of the Bombyx Australis. The eggs were pear-shaped, mottled with dirty brown, on a greenish grey ground. Another nest, found at Mount Ernest, Jones's Straits, differs from those seen in Cape York, in having over the entrance a projecting fringe-like hood, composed of the panicles of a delicate grass-like plant. It contained two young birds, and I saw the mother visit them twice in an interval of ten minutes. She glanced past like an arrow, perched at once on the nest, clinging to the lower side of the entrance, and looked round very watchfully for a few seconds before feeding the young, after which she disappeared as suddenly as she arrived."

The SPIDER-EATERS (Arachnothera) are short, compactly-built birds, with extraordinarily long and often strangely-formed beaks, which in most species are very decidedly curved and delicately incised at the margins. The nostrils are covered with a skin, and only open inferiorly,[8] where they terminate in a horizontal slit-shaped aperture. The thread-like tongue, which is very long, and greatly resembles that of a butterfly, consists of two fine tubes, which run side by side, and are closely connected along their under surface; a longitudinal groove is interposed between them above. The arrangement of the bones at the base of the tongue, whereby the lingual apparatus is capable of considerable protrusion, is very similar to that observable in the Woodpecker. The feet are powerful, but of medium length, and the wings (in which the fourth quill is the longest) are of moderate size. The sexes are very similar in the coloration of their plumage, in which brownish green, and more or less lively yellow, grey, or green, predominate.

The Spider-eaters usually frequent the most shady retreats in their favourite woods, and but rarely ascend the branches to more than fifteen or twenty feet from the ground. In the Sunda Islands they are principally met with in the coffee plantations, the brushwood that skirts the mountains, or in the thickets of trees and shrubs that surround the villages. In all these situations they are numerous, and are constantly to be seen as they flit from flower to flower in search of the insects and honey upon which they subsist. Small spiders are said to be eagerly devoured by all the members of this family, hence their name of Arachnothera. The flight of the Spider-eaters, which is extremely rapid, and in many respects like that of the Woodpecker, is observed by the natives with a superstitious attention, fully equalling the reverence paid by the Romans to the predictions drawn by their augurs from a similar source.

The HALF-BILLS (Hemignathus) are a group of Spider-eaters that are easily recognisable by the strange formation of their beak; the upper mandible terminates in a sharp point, and is always much longer than the under portion of the bill, sometimes twice its length. The toes, also, are comparatively long, and the foot short. The plumage is usually green upon the back, and of a yellowish tint beneath. All the members of this group inhabit Oceania.

THE BRILLIANT HALF-BILL.

The BRILLIANT HALF-BILL (Hemignathus lucidus), one of the most beautiful members of this group, is olive-green upon the entire mantle, shading into grass-green on the top of the head and at the edges of the wings. A stripe over the eyes, and the sides of the head and throat are orange-red; the breast is bright yellow, the belly of a paler shade, and its lower portion greenish grey. In young birds the back and region of the eye are olive-green, the under side light greenish grey, and the belly pale yellow. This species is six inches long, but of this measurement one inch and three-quarters belong to the tail, and one inch and a quarter to the beak; the lower mandible does not exceed eight lines in length. We are without particulars as to the life of this bird, except that it inhabits the Pisang plantations.

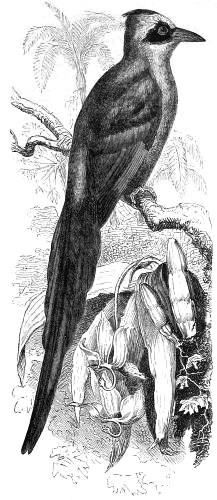

The HANGING BIRDS (Arachnocestra) are recognised by the great length of their slightly-curved beak, the base of which is as broad as it is high; the upper mandible is delicately incised, and the entire bill of almost equal thickness, only tapering gently towards the extremity; the legs are slender, the toes long, and the wings (in which the fourth, fifth, and sixth quills exceed the rest in length) of moderate size; the tail is short and rounded.

THE TRUE HANGING BIRDS.

The TRUE HANGING BIRDS (Arachnocestra longirostris) are olive-green on the back, and sulphur-yellow on the under side; the throat and upper breast are white, the quills and tail-feathers deep brown, the former edged with olive, and the three outer tail-feathers tipped with white; the beak and[9] feet are blackish grey. This species is six inches and a half long, the wing measures two inches and two-thirds, and the tail one inch and three-quarters.

THE HANGING BIRD (Arachnocestra longirostris).

These birds frequent banana plantations, and usually betray their presence by their shrill chirping cry. Were it not for the constant repetition of their note they would rarely be observed, as the hues of their plumage render it almost impossible to detect them among the foliage. We learn from Bernstein that their manner of building is very remarkable. The oval-shaped nest, some six or seven inches long, and three or four inches broad, is attached by threads to a large leaf, in such a manner that the latter forms the fourth side. Fine grass and fibres are employed for the interior, and half-decayed leaves, of which little more than the fibrous portion remains, are used for the outer wall, so that, when completed, the curious structure has rather the appearance of a substantial spider's web than of a bird's nest. The entrance is at one end. The eggs, two in number, are pure white, spotted with reddish brown at the broad extremity.

The HONEY-EATERS (Meliphaga) have a long, slender, slightly-curved beak, the upper mandible of which extends considerably beyond the lower portion. The feet are strong but moderate-sized, and furnished with powerful hinder toes; the wing, also moderate, is rounded, its fourth quill being the longest; the tail varies in its dimensions, but is usually rounded at its extremity; the nostrils are concealed by a cartilaginous skin; the gape is narrow, and the tongue provided with a tuft of delicate fibrous bristles at its tip. The stomach is very small, and but slightly muscular. The plumage, which differs little in the two sexes, varies considerably in different species. In some it is thick, variegated, and much developed in the region of the ear, in others smooth, compact, and of almost uniform colour.

All the Honey-eaters are of a lively and restless disposition, and exhibit the utmost activity both when running upon the ground or climbing amongst the branches; in the latter case, especially, their movements are extremely agile. They are constantly to be seen hanging head downwards from the twigs, whilst engaged in busily searching under the leaves for insects, and in extracting honey from the flowers. Some species fly well, and disport themselves freely in the realms of air, whilst others are incapable of continuing their undulatory flight for more than a short distance. The voice of all is rich and varied, indeed, some members of the group may be regarded as really good singers. Few species are social in their habits; they keep together only in pairs, even when of necessity compelled to take up their abode near each other. Towards man they show the utmost confidence, and come freely down into streets and dwellings; indeed, they exhibit no timidity even towards the more formidable of the feathered kind. Instances have been frequently recorded in which they have boldly opposed Crows, Falcons, and other large birds. Their nests are variously constructed, and the number of eggs is always small.

The TRUE HONEY-EATERS (Myzomela) are small birds, with delicate, much curved beaks, powerful feet, and moderate-sized wings and tail. The latter is either straight or slightly incised at its extremity. The plumage is remarkable for its brilliancy.

THE RED-HEADED HONEY-EATER.

The RED-HEADED HONEY-EATER (Myzomela erythrocephala) is a beautiful species, bright scarlet upon the head, throat, and rump; the tail and a band upon the breast are chocolate-brown; the lower breast and belly are brownish yellow, the eye is reddish brown, the beak olive-brown, and the foot olive-grey. The female is brown above, and light fawn-colour on the under side. The length of this species is four inches and a half. The wing measures two inches and a quarter, and the tail one inch and three-quarters.

This magnificent little bird frequents the groves and groups of almond-trees that abound in the northern parts of Australia, and enlivens its favourite haunts as much by the briskness and activity of its movements as by the brightness of its plumage. Its voice is sharp and twittering. We are entirely without particulars of the manner in which incubation is carried on.

The TUFTED HONEY-EATERS (Ptilotis) are remarkable for the unusual development of the feathers in the region of the ear. Their body is elongate, their wings short, and tail long. The strong, slightly-curved beak is short, and the foot of moderate size.

THE YELLOW-THROATED TUFTED HONEY-EATER.

The YELLOW-THROATED TUFTED HONEY-EATER (Ptilotis flavigula) is yellowish green on the back, wings, and tail. The dark grey under side glistens with a silver sheen; the belly and sides are pale olive, the top of the head dark grey, and the throat bright yellow. The feathers that compose the ear-tufts are tipped with yellow, and the outer web of the quills is deep brown. The eye is brown, the beak black, and the foot lead-grey; the gullet and tongue are of a brilliant orange-red. The length of this bird is eight inches; the wing measures four inches and a half, and the tail four inches and a quarter.

"This fine and conspicuous species," says Gould, "is abundant in all the ravines around Hobart Town, and is very generally spread over the whole of Van Dieman's Land, to which island I believe it to be exclusively confined. It is very animated and sprightly, extremely quick in its actions, elegant in its form, and graceful in all its movements; but as its colouring assimilates in a remarkable[11] degree with that of the foliage it frequents, it is somewhat difficult of detection. When engaged in searching for food, it frequently expands its wings and tail, creeps and climbs among the branches in a variety of beautiful attitudes, and often suspends itself to the extreme ends of the outermost twigs. It occasionally perches on the branches of trees, but is mostly to be met with in dense thickets. It flies in an undulating manner, like a Woodpecker, but this power is rarely exercised. Its note is a full, loud, powerful, and melodious call. The stomach is muscular, but of very small size, and the food consists of bees, wasps, and other hymenoptera, also of coleoptera of various kinds, and the pollen of flowers. It is a very early breeder, as is proved by my finding a nest containing two young birds covered with down, and about two days old, on the 27th of September. The nest, which is generally placed in a low bush, differs considerably from those of all other Honey-eaters with which I am acquainted, particularly in the character of the material forming the lining. It is the largest and warmest of all, and is usually formed of ribbons of stringy bark, mixed with grass, and the cocoons of spiders; towards the cavity it is more neatly built, and is lined internally with opossum's or kangaroo's fur. In some instances the hair-like material from the base of the large leaf-stalks of the tree-fern is employed for the lining, and in others there is merely a flooring of wiry grasses or fine twigs. The eggs, which are either two or three in number, are of the most delicate fleshy buff, rather strongly but sparsely spotted with small prominent roundish dots of chestnut-red, intermingled with which are a few indistinct spots of purplish grey. The average length of the egg is eleven lines, and the breadth eight lines."

The BRUSH WATTLE BIRDS (Melichæra) are recognisable by their powerful body, strong and slightly curved beak, comparatively short foot, short rounded wing, and long, wedge-shaped, tapering tail.

THE TRUE BRUSH WATTLE BIRD.

The TRUE BRUSH WATTLE BIRD (Melichæra mellivora) is deep brownish grey on the back, each feather having a white stripe in the centre. The feathers on the throat and breast are brown, tipped with white; the rest of the under side appears lighter than the back, owing to the greater size of the white shaft-stripe. The upper quills are chestnut-brown on the inner web, and the rest brown tipped with white, as are the tail-feathers. The eye is grey, the beak black, and the foot brown. This species is about eleven inches long; the wing measures four inches and a quarter, and the tail five inches and one-sixth.

These birds inhabit all such parts of Tasmania, New South Wales, and South Australia as offer them the shelter of their favourite Banksias. Everywhere they are numerous, and display the utmost confidence and fearlessness towards man. In disposition they are lively, active, and so pugnacious as to live in a state of constant warfare with all their feathered companions. "The Brush Wattle Bird," says Gould, "is a bold and spirited species, evincing a considerable degree of pugnacity, fearlessly attacking and driving away all other birds from the part of the tree on which it is feeding, and there are few of the Honey-eaters whose actions are more sprightly and animated. During the months of spring the male perches on some elevated branch, and screams forth its harsh and peculiar notes, which have not unaptly been said to resemble a person in the act of vomiting; whence the Australian name of 'Goo-gwar-ruck,' in which the natives have endeavoured to imitate these very singular sounds. While thus employed, it frequently jerks up its tail, throws up its head, and distends its throat, as if great exertion were required to force out these harsh and guttural sounds. The Banksias are in blossom during the greater portion of the year, and the early flower, as it expands, is diligently examined by the Wattle Bird, which inserts its long feathery tongue into the interstices of[12] every part, extracting the pollen and insects, in searching for which it clings to and hangs about the blossoms in every variety of position. The breeding season commences in September, and lasts for three months. The very small nest is round in shape, open at the top, and formed of delicate twigs and fibres. This pretty little structure is usually placed in the fork of a branch, at the height of a few feet from the ground. The two or three eggs are bright red, spotted slightly with dark brown; these markings are most numerous at the broad end."

THE POE, OR TUI.

The POE, or TUI (Prosthemadera circinata), is readily distinguished by the two remarkable tufts of feathers that decorate each side of the throat; in other respects its formation closely resembles that of its congeners. The coloration of the plumage is principally of a deep metallic green, which appears black in some lights, and in others shines like bronze. The back is umber-brown, but glistens with the same varying shades. A white line passes over the shoulders, and the long feathers on the nape are enlivened by white streaks upon the shafts. The strange tufts on the sides of the throat to which we have alluded are pure white, and form a dazzling contrast to the dark plumage by which they are surrounded. The belly is deep umber-brown; the quills and tail-feathers black, very glossy and resplendent above, and quite lustreless on the lower side. This species is twelve inches long. The wing measures five inches and a half, and the tail four inches and a half. Layard tells us that of all the feathered inhabitants of the New Zealand forests the Poe is most certain to attract the notice of the traveller, as it flutters noisily from branch to branch, or sails in airy circles over the tree tops. It is not uncommon to see eight or ten of these birds at a time turning somersaults as they circle after each other, or rise and sink with outspread wings and tail, until at last they return to seek repose after their gambols under the sheltering branches of the trees. The Poe has been frequently described as the most wonderful of songsters, and some writers have gone so far as to declare that its performance far exceeds that of the Nightingale, both in beauty of tone and clearness of execution. Such accounts as these are, in our opinion, much exaggerated, though we admit that it certainly ranks with the finest songsters inhabiting Australia. The food of the Poe, we are told, consists of insects, in search of which it exhibits a very restless activity. It also devours berries and earthworms. This species possesses a most wonderful talent for imitating the notes of all the feathered inhabitants of the woods; hence it is sometimes called the Mocking Bird. In confinement it also learns to mimic other sounds, such as the noises of dogs, cats, or poultry, and readily pronounces long sentences with great correctness.

The FRIAR BIRDS (Tropidorhyncus) are recognisable from all their congeners by a knob at the base of the upper mandible, a bare place on the head and throat, and the long feathers that adorn the nape or breast. The tongue is provided at its extremity with a double brush-like appendage.

THE "LEATHERHEAD."

The "LEATHERHEAD" (Tropidorhyncus corniculatus) is greyish brown on the back and brownish grey upon the under side, a long lancet-shaped feather on the breast, and the chin-feathers, are of a pure glossy white, delicately spotted with brown; the tail is tipped with white. The eye is red, but turns brown after death; the beak, and some bare places on the head, are of silky blackness, and the feet lead-grey. The female is smaller than her mate, and the young are distinguishable from the adult birds by the inferior size of the knob on the beak and of the breast-feathers; the bare places on the head are also smaller. This species is about twelve inches long, the wing measures five inches and three-quarters, and the tail four inches and two-thirds.

Gould tells us that in New South Wales these birds are very common during the summer, and are especially numerous in the thick brushwood near the coast. Their undulatory flight is strong, and their movements amongst the branches nimble and adroit; it is by no means uncommon to see them hanging head downwards from a branch to which they attach themselves solely by one of their powerful claws; such formidable use, indeed, do they make of these sharp weapons, that he who unwarily seizes a wounded bird is sure to receive a series of deep and really painful wounds in repayment of his temerity.

THE POE, OR TUI (Prosthemadera circinata).

The strange cry of this species has been supposed to resemble the words, "Poor soldier," "Pimlico," and "Four o'clock," while the bare places on its head have procured for it the names of "Monk," "Friar," and "Leatherhead." Figs, berries, insects, and the pollen from the gum-tree blossoms constitute its favourite and principal means of existence. At the approach of the breeding season, which commences about November, the males become more than usually active and bold, chasing and doing battle with even the most formidable of their feathered brethren should they intrude upon the privacy of the brooding female. The comparatively large and cup-shaped nest is roughly formed of bark, twigs, and wool; the interior lined with more delicate materials. This structure is generally suspended from an upright branch of a gum or apple tree (Angophora), and is often found at but a few feet from the ground. In the well-wooded plains of Aberdeen and Yarrund, on the upper part of the Hunter, this species breeds in such numbers that the nests may almost be[14] described as forming settlements. The eggs, usually three in number, are pale red, delicately spotted with a deeper shade.

The HOOPOES (Upupa) may be regarded as the most aberrant of the Tenuirostral group. They are moderately large, and slenderly formed; their beak is long, slender, higher than it is broad, and in some species much curved; the small, oval, and open nostrils are situated immediately beneath the feathers that cover the brow; the strength of the foot varies considerably; the wings (in which the fourth and fifth quills are the longest) are much rounded; the tail, formed of ten feathers, is either short and straight at its extremity or long and graduated. The compact and variegated plumage differs considerably as to its coloration, and but little variety is observable between the two sexes.

THE HOOPOE.

The COMMON HOOPOE (Upupa epops) is recognisable by its elongate body; long, slender, slightly curved, and pointed beak (which is much compressed at its sides); and short powerful foot armed with blunt claws. The wing is decidedly rounded; the tail of moderate size, composed of broad feathers, and straight at its extremity. The soft, lax plumage, which is prolonged into a crest on the top of the head, is much variegated, and almost alike in the various species with which we are acquainted. Reddish brown of a more or less lively hue usually predominates in its coloration, while the wings and tail are striped with white. In the Common Hoopoe the upper portion of the body is of reddish brown, variegated with black and yellowish white on the middle of the back, and on the shoulder and wings. The crest is of a deep reddish yellow, tipped with black; the under side is bright reddish yellow, spotted with black on the sides of the belly; the black tail is striped with white about its centre. All the colours in the plumage of the female are duller than in that of her mate. The young are recognisable by the comparative smallness of their crest. The eye is deep brown, the beak greyish black, and the foot lead-grey. The length of this species is about ten and its breadth eighteen inches. The wing measures five, and the tail four inches.

The greater portion of Europe, Northern Africa, and Central Asia are inhabited by these birds, which are specially numerous in the more southern portions of those regions, and instances are recorded of stragglers having been seen as far north as the Loffoden Isles. In some of the central provinces of Europe they appear about the end of March, and leave again in pairs, or small parties, at the commencement of autumn. Such as inhabit North-eastern Africa do not migrate, but merely wander at certain seasons over the surface of the country. In Southern Europe these birds frequent the vineyards, but in North-eastern Africa they prefer the immediate vicinity of towns and villages, and render great benefits to the inhabitants by assisting the Vultures, whose proceedings we have already described, in their revolting but most valuable labours.

Anything like sociability is unknown to this bird; each lives for its mate or its family alone, and carries on a constant warfare with all its neighbours. Strange to say, however, if taken young from the nest they soon become extraordinarily tame, and learn to obey and follow those who feed them with all the fidelity and devotion of a favourite dog. Carrion, beetles, larvæ, caterpillars, ants, and many other kinds of insects are devoured by the Common Hoopoe in large numbers, its long beak enabling it to search for its victims in any hole or crevice into which they may have crept. Large beetles are killed by repeated blows, and by crushing them against the ground until the wings and feet have been broken off. The morsel is then tossed aloft and dextrously caught and swallowed. The young birds are at first unable to perform this rather difficult feat, and, therefore, require to be fed by those who may wish to rear them. It would appear that but little care or fastidiousness is exhibited in selecting a spot suitable for building their nests: trees, fissures in walls, houses, or holes in the[15] ground are indiscriminately employed; and Pallas mentions having found a nest containing seven young in the thorax of a human skeleton. Dry grass, roots, and cow-dung are the materials employed in the construction of the nest. The brood consists of from four to seven small elongate eggs, with a dirty greenish white or yellowish grey shell, occasionally finely spotted with white. The female alone broods, and the young are hatched in a fortnight. Both parents assist in the task of feeding their charge, and tend them with much affection; this care, however, does not extend to clearing away such daily accumulations as are usually removed, and the consequence is that before the family are fully fledged the nest has become a mere mass of seething flies and maggots, giving forth a stench from which the birds themselves are only freed after having been exposed for many successive days to the pure winds of heaven.

The TREE HOOPOES (Irrisor) inhabit the forests of Africa, and are recognisable by their slender body, long beak, short foot and wing, and long tail. The slightly-curved beak has a ridge at its margin, and is compressed at its sides. The powerful tarsus is much shorter than the centre toe, which, like the rest, is armed with a strong hooked claw. The fourth and fifth quills of the rounded wing exceed the rest in length; and the broad tail is much graduated. Those species with which we are familiar inhabit the forests of Central and Southern Africa, and pass their lives exclusively upon trees.

THE RED-BEAKED TREE HOOPOE.

The RED-BEAKED TREE HOOPOE (Irrisor erythrorhyncus). The prevailing colour of this species is a beautiful metallic blue, shimmering with dark green and purple. The inner web of the first three quills is decorated by a single white spot, whilst the six next in order have two white spots. The three first tail-feathers are similarly adorned, and are also marked with white near the tip. The eye is brown, and the beak and foot bright red. The female is smaller, and her plumage less glossy. The young are deep green, nearly black, and almost lustreless. This species is from seventeen to eighteen inches long, and eighteen inches and a half broad. The wing measures six, and the tail nine inches.

According to our own observations these beautiful birds principally inhabit the forests of North-eastern Africa, and are usually met with hopping or climbing incessantly from tree to tree, or bough to bough, in parties of from four to ten. These parties exhibit extraordinary unanimity in their manner of proceeding, and in all their movements seem to be playing an active game of follow-my-leader. Should one member of the little society suspend itself from a branch, all the rest immediately do the same; and even when uttering their cry as they rise into the air, the sounds are often so simultaneous that it is almost impossible to distinguish the individual voices. Ants and, according to some authorities, various kinds of insects, constitute their principal food. Few birds exhibit such strong attachment to their companions as we have frequently observed amongst groups of Tree Hoopoes; it is not uncommon for them to remain close together as though for mutual defence until repeated shots from the hunter's gun have brought one of the party to the ground, when the rest come rushing down, flapping their wings and uttering loud cries as they settle on the branches depending over the spot on which the victim lies. Despite the shortness of their legs, they run over the ground with tolerable ease. Their flight alternates between a gentle gliding motion and a series of rapid strokes with the pinions. Le Vaillant tells us that the female deposits her bluish green eggs, from four to six in number, at the bottom of a hole in a tree, and is assisted in the labour of incubation by her mate.

The TREE-CLIMBERS (Anabata) constitute a family of South American birds, with slender bodies, short wings, and long tails. Their straight or but slightly curved beak is strong, and of the[16] same length as the head. The tarsi are of medium height; the toes small, armed with short and slightly-curved claws. The fourth quill of the wings is the longest. The very decidedly graduated tail is composed of twelve short feathers. All the members of this family inhabit forest or woodland districts, and but rarely venture forth into the open country. Insects form almost exclusively their means of subsistence; and in search of these they climb the branches with an agility fully equalling that of the Titmouse. Many species are remarkable for the peculiarity and loudness of their cry. Their nests, which are usually suspended from the trees, and closed above, are frequently very striking in appearance.

THE HOOPOE (Upupa epops).

The BUNDLE-NESTS (Phacellodomus) are recognisable by their short, almost straight beak, which is much compressed, and very slightly hooked towards its tip. The tarsi are high and strong; the wings rounded; and the broad tail formed of narrow, soft feathers.

THE RED-FRONTED BUNDLE-NEST, OR CLIMBING THRUSH.

The RED-FRONTED BUNDLE-NEST, or CLIMBING THRUSH (Phacellodomus rufifrons), is of a light brownish greenish grey on the upper parts of the body, and light brownish white on the under side. The quills are greyish brown, with a reddish gloss on the outer web; the brow is deep rust-red, and a stripe over the eyes pure white. The eye is grey, the upper mandible dark greyish brown, and the lower one whitish grey. The foot is pale blueish grey. This species measures six inches and a quarter, the wing two inches and a quarter, and the tail two inches and a half.

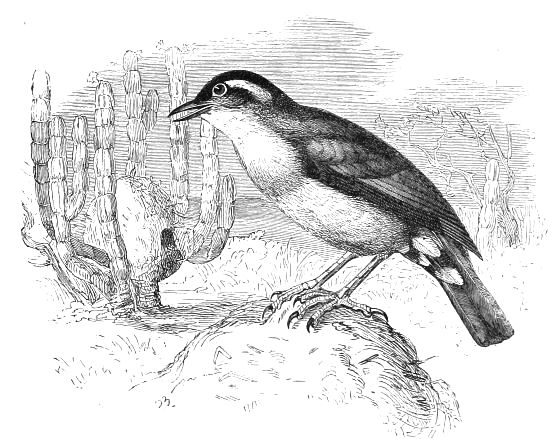

THE RED OVEN BIRD (Furnarius rufus).

The Prince von Wied tells us he only met with these elegant little birds upon the arid interior highland tracts of Geroes and Bahia, where they inhabited the open country, and passed their time in hopping or flying from one bush or tree to another. As regards its nidification, the Prince von Wied remarks, "I found the nests of the Phacellodomus rufifrons about February; they were usually suspended on the low, slender branches of high trees. Those I saw are best described as large oval bundles, often more than three feet long, and formed of thin twigs heaped together and interwoven with each other, or fastened together by a variety of materials. The interior was filled with small bundles of moss, hair, wool, or fibres interlaced, so as to form a warm and compact lining. The small round hole that serves as an entrance is situated at the bottom of this suspended mass, so that the birds ascend from below into their huge domicile. Year by year these nests are added to and enlarged until at last it is not uncommon to find that they have so increased in size as to render it a difficult task for a man to stir one of them. On opening a nest of this description a row of chambers is seen, under the one last made." These ancient apartments are, we believe, frequently employed as[18] retiring-rooms for the male parent. Swainson tells us that these strange and shapeless masses are very conspicuous features in the landscape. The brood usually consists of four eggs, which are round in shape, and generally of a pure white.

The OVEN BIRDS (Furnarius) possess a moderately strong beak, either quite straight or slightly curved, compressed at its sides, and almost equalling the head in length; the blunt wing is of medium size, its third quill is the longest, while its first is considerably, and its second slightly shortened; the short tail is composed of soft feathers; the tarsus is high, and the toes strong; the claws are somewhat hooked, but only the first is of any considerable size. These birds frequent both open woodlands and inhabited districts; they live for the most part on the ground, as their powers of flight and climbing are very limited. Their voice is loud, harsh, and peculiar. The strange nests built by the members of this group, and from which their name is derived, have been described by Azara, the Prince von Wied, Burmeister, Darwin, and other writers. "After passing over the lofty chain of mountains that separate the well-wooded coasts of Brazil from the Campos, travellers are astonished at beholding large, melon-shaped masses of clay standing erect upon the branches of the high trees surrounding the settlers' houses. Were it not for the regularity of their size and shape, a stranger would at once pronounce these masses of clay to be nests built by the termite ants. On closer inspection of one of these the eye detects an oval-shaped hole at the side, and a little patience is rewarded by a sight of the actual inhabitant of this most remarkable nest as he slips in and out of the entrance to his strange abode. This bird, known to us as the Furnarius rufus, is called the João de Barro, or Clay Jack, by the Brazilians." We learn from Darwin that these nests are also placed in such exposed situations as the top of a post, a bare rock, or on a cactus, and are composed of mud and bits of straw. The strong, thick walls in shape precisely resemble an oven, or a depressed bee-hive. The opening is large, and directly in front; within the nest there is a partition, which reaches nearly to the roof, thus forming a passage or antechamber to the true nest.

THE RED OVEN BIRD.

The RED OVEN BIRD (Furnarius rufus) is about seven inches long and ten and a half broad; the wing measures three inches and three-quarters, and the tail three inches. The plumage is principally of a reddish yellow; the top of the head brownish red, and the quills brown; the under side is of a lighter tint, and the throat pale white; a bright reddish yellow stripe passes from the eyes to the back of the head; the quills are grey, the primaries edged with pale yellow towards their base, and the tail-feathers yellowish red; the eyes are yellowish brown, the beak brown, except at the whitish base of the lower mandible; the foot is also brown.

These strange birds live in pairs, and but rarely associate, even in small parties. Their food consists of insects and various kinds of seeds, the former, according to Burmeister, being always obtained from the surface of the ground, over which they run and hop with great facility. Nor are their movements less adroit amongst the branches, from whence their most peculiar cry is constantly to be heard as they disport themselves from bough to bough. These birds are regarded with great respect by the Brazilians, on account of a very strange but prevalent idea that they never proceed with their building operations on the Sabbath, a superstitious fancy that we need hardly say has been frequently disproved, but has no doubt arisen from the unusually short time required by this species to complete its remarkable and elaborate home.

"The nest of the Red Oven Bird," says Burmeister, "is usually constructed upon the branch of a tree, and occasionally upon house-tops, steeples, or similar situations. Both male and female unite in the labour of building, and form their nests of round pellets of mud, working each pellet[19] firmly into place, intermixed with small portions of plants, until the foundation is some eight or nine inches high. On each end of this groundwork the birds proceed to erect a side wall of such a form and height as to give the entire mass the appearance of a half-crescent. When this foundation is quite dry a second wall of similar shape is erected within the first. This again is left to dry, and so the work proceeds until the mass has assumed the proper dome-like form, and is six or seven inches in height, eight or nine inches long, and some four or five inches deep. The interior of this remarkable structure (which sometimes weighs as much as nine pounds) is entered by an oval-shaped hole at the side, and is neatly and warmly lined with hay, cotton, wool, feathers, or similar materials. The eggs, from two to four in number, have a white shell, and are incubated by both parents. The first brood is produced early in September, and a second later in the season."

The GROUND WOODPECKERS (Geositta) are birds with slender bodies, long, pointed wings, and short incised tails; the slightly curved beak is triangular at its base, and nearly equals the head in length; the legs are of medium height, the outer toes short, and the claws small.

THE BURROWING GROUND WOODPECKER.

The BURROWING GROUND WOODPECKER (Geositta cunicularia) is of a deep brown on the upper portions of the body and wings; the under side is pale brown, the throat whitish, breast spotted and striped with black, and the belly rust-red. The region of the eye is pale red, the shoulder-feathers have light edges, and the exterior quills are bordered and tipped with blackish brown, and shaded with red upon the inner web. The eye is brown, the beak whitish at its base and black towards its tip; the feet are blackish brown. According to Kittlitz these birds inhabit the barren plains of Chili and Patagonia, and are met with on the Bolivian Cordilleras to a height of from 3,500 to 4,500 feet above the level of the sea. We learn from the same authority that in its general habits the Geositta cunicularia closely resembles the Common Lark.

"The Casaeita, as this bird is called by the natives," says Darwin, "builds its nest at the bottom of a narrow cylindrical hole, which is said to extend horizontally to nearly six feet under ground, in any low bank of sandy soil by the side of a wood or stream. Here, at Bahia Blanca, the walls of those I have seen are built of hardened mud. I noticed that a bank that enclosed the courtyard of the house where I lodged was penetrated by round holes in a score of places. On asking the owner the cause of this, he explained that they were made by the Casaeitas, several of which I afterwards saw at work. It is strange that though the birds were constantly flitting over the low wall they were evidently incapable of forming an idea as to its thickness, otherwise they would not have made so many vain attempts. I do not doubt that each bird as it came to daylight on the opposite side was greatly surprised at the marvellous fact."

Gray tells us that this species is extremely tame, and almost constantly in motion. The stomachs of such as he examined contained the remains of beetles; whilst Kittlitz mentions having only found seeds and small stones. At certain seasons the call is a shrill, tremulous note.