The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of England, by J. Franck Bright

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: A History of England

Period I, Mediaeval Monarchy

Author: J. Franck Bright

Release Date: February 9, 2020 [EBook #61358]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF ENGLAND ***

Produced by Jane Robins, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

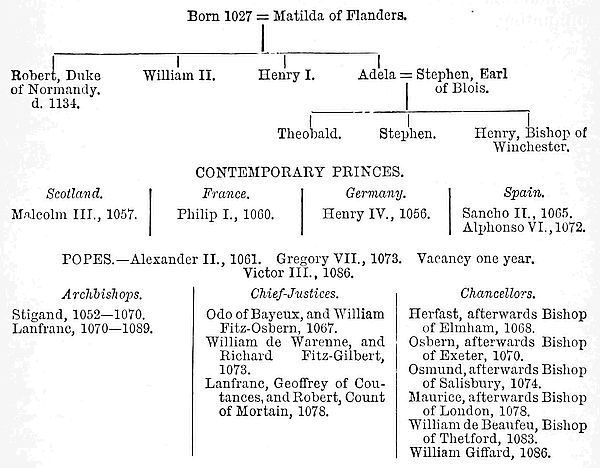

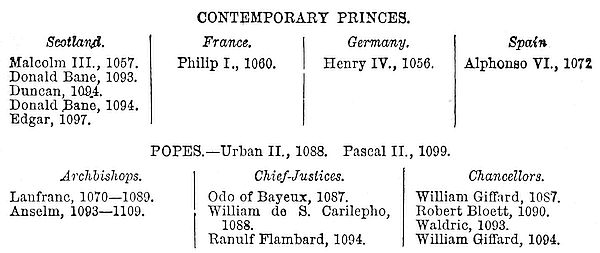

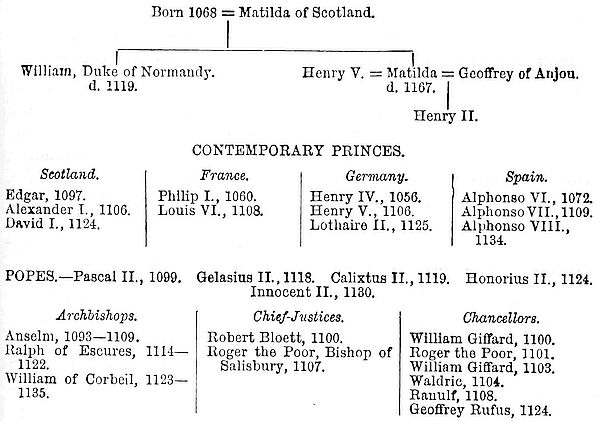

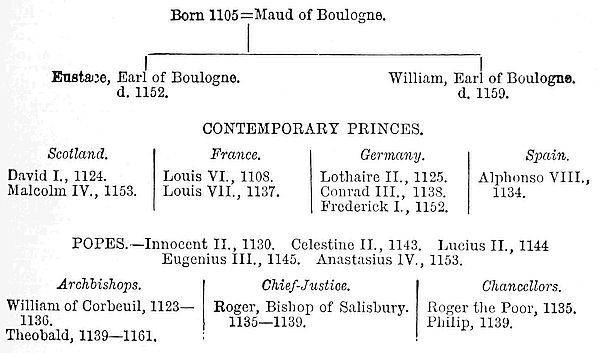

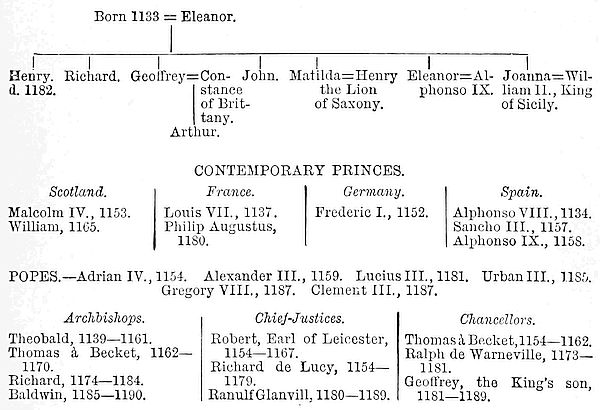

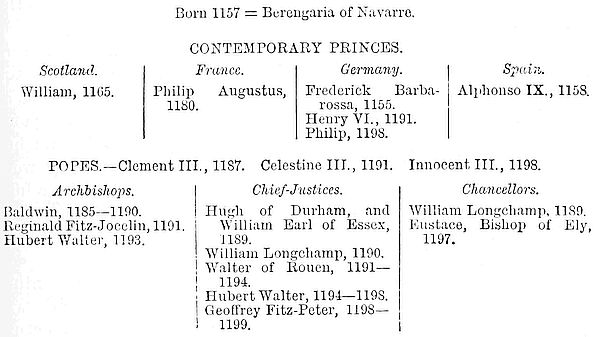

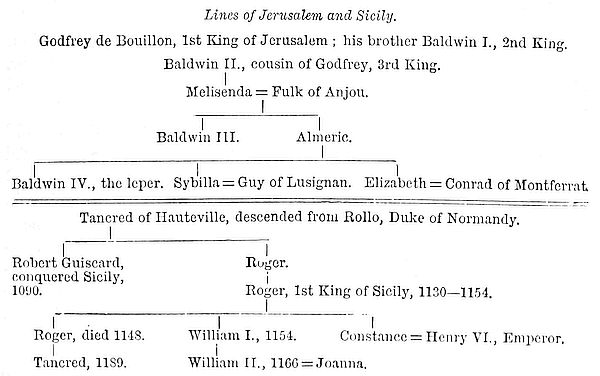

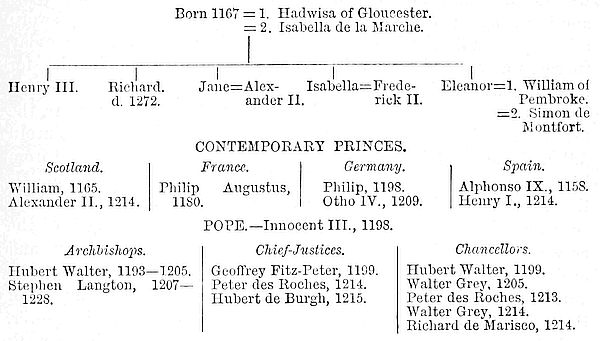

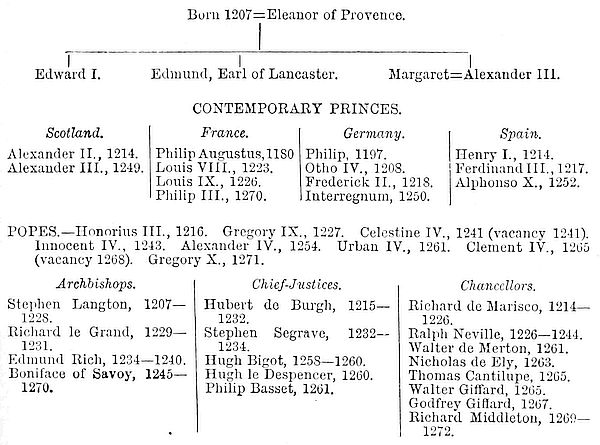

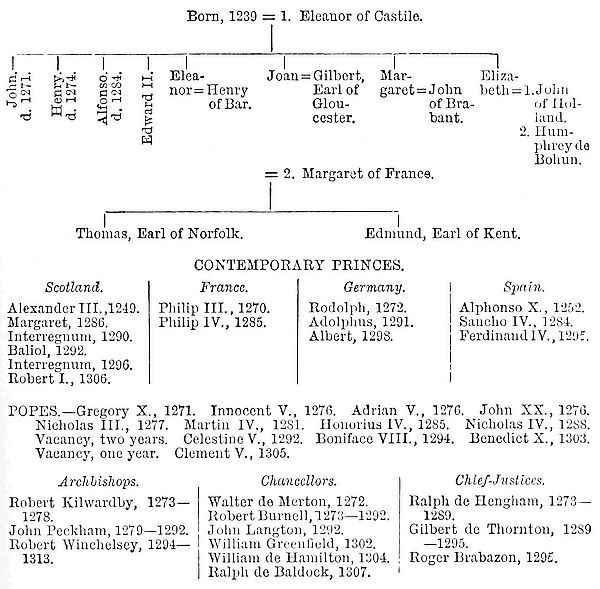

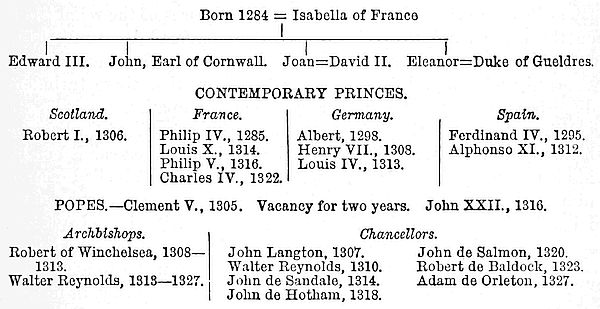

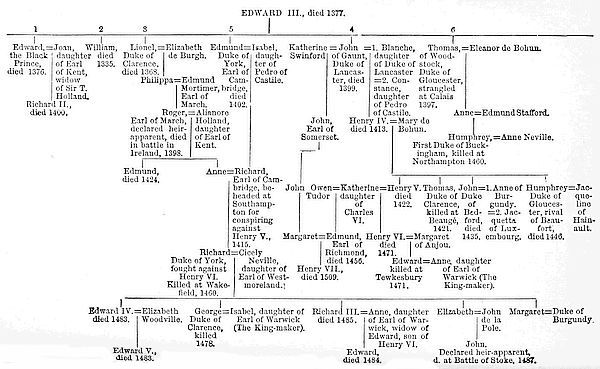

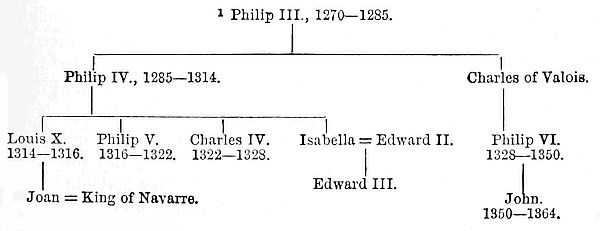

The genealogical tables and the many sidenotes in some paragraphs are best viewed using a smaller-size font.

The genealogical tables are displayed in image form only on handheld devices, but are available in searchable text format in the .txt and .htm versions of this ebook.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

A HISTORY OF ENGLAND.

By the Rev. J. Franck Bright, M.A., Fellow of University College, and Historical Lecturer in Balliol, New, and University Colleges, Oxford; late Master of the Modern School in Marlborough College.

With numerous Maps and Plans. Crown 8vo.

This work is divided into three Periods of convenient and handy size, especially adapted for use in Schools, as well as for Students reading special portions of History for local and other Examinations.

Period I.—Mediæval Monarchy: The Departure of the Romans, to Richard III. From A.D. 449 to A.D. 1485. 4s. 6d.

Period II.—Personal Monarchy: Henry VII. to James II. From A.D. 1485 to A.D. 1688. 5s.

Period III.—Constitutional Monarchy: William and Mary to the Present Time. From A.D. 1689 to A.D. 1837. 7s. 6d.

[All rights reserved.]

A

History of England

BY THE REV.

J. FRANCK BRIGHT, M.A.

FELLOW OF UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, AND HISTORICAL LECTURER IN BALLIOL, NEW, AND UNIVERSITY COLLEGES, OXFORD; LATE MASTER OF THE MODERN SCHOOL IN MARLBOROUGH COLLEGE

PERIOD I.

MEDIÆVAL MONARCHY

From the Departure of the Romans to Richard III.

449–1485

With Maps and Plans

RIVINGTONS

WATERLOO PLACE, LONDON

Oxford, and Cambridge

MDCCCLXXVII

[Second Edition, Revised]

The object of this book is expressed in the title. It is intended to be a useful book for school teaching, and advances no higher pretensions. Some years ago, at a meeting of Public School Masters, the want of such a book was spoken of, and at the suggestion of his friends, the Author determined to attempt to supply this want. The objections raised to the school histories ordinarily used were—first, the absence of historical perspective, produced by the unconnected manner in which the facts were narrated, and the inadequate mention of the foreign relations of the country; secondly, the omission of many important points of constitutional history; thirdly, the limitation of the history to the political relations of the nation, to the exclusion of its social growth. It was at first intended to approach the history almost entirely on the social and constitutional side; but a very short trial proved that this method required a too constant employment of allusions, and presupposed too much knowledge in the reader, to be suitable for a book intended primarily for schools. It was therefore resolved to limit the description of the growth of society to a few comprehensive chapters and passages, and to follow the general course of history in such a way as to bring out as clearly as possible the connection of the[vi] events, and their relative importance in the general national growth. This decision, though taken against his inclinations, the Author can no longer regret, as the social side of our history has been so adequately treated by Mr. Green in his History of the English People, of the approaching publication of which he was at the time quite ignorant. On the same grounds of practical utility, it has been thought better to retain the old and well-known divisions into reigns, rather than to disturb the knowledge boys have already gained by the introduction of a new though more scientific division.

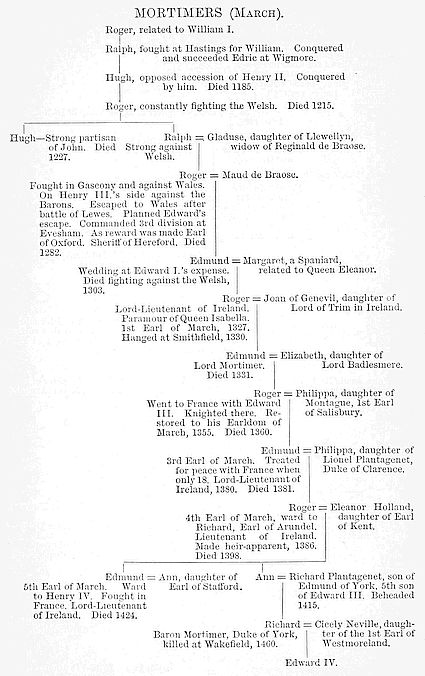

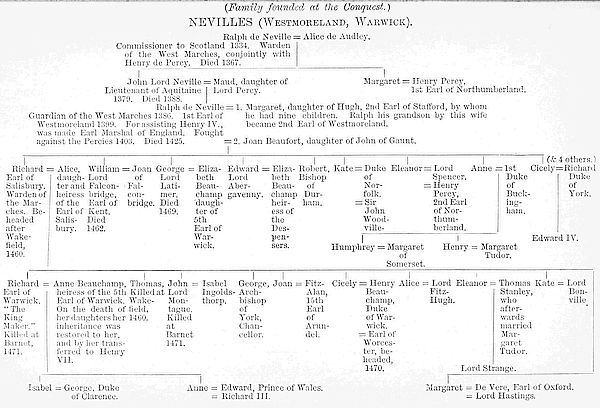

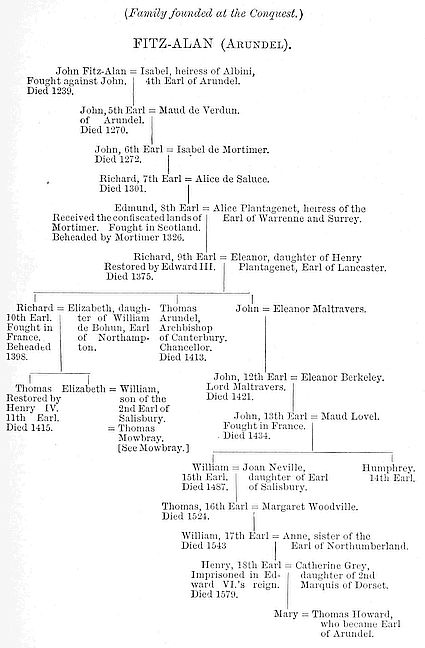

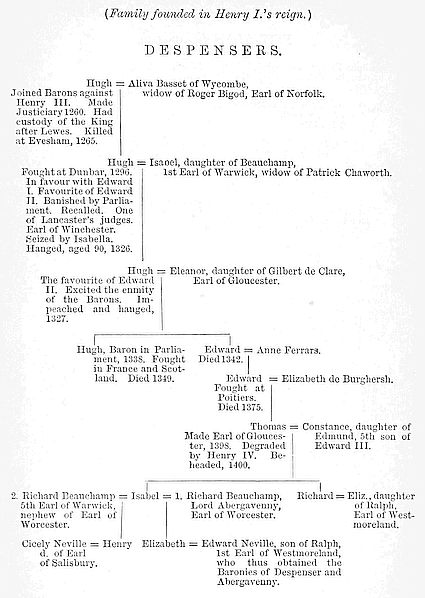

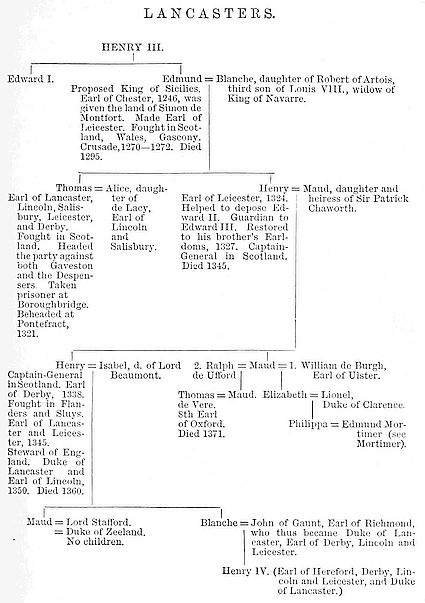

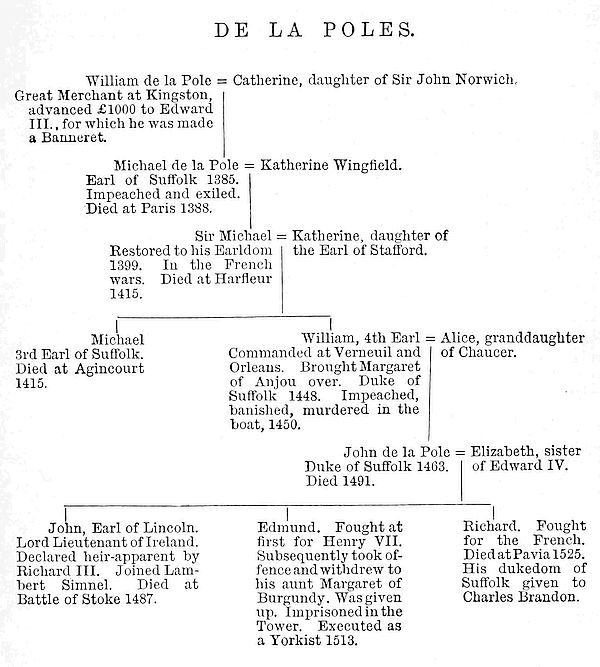

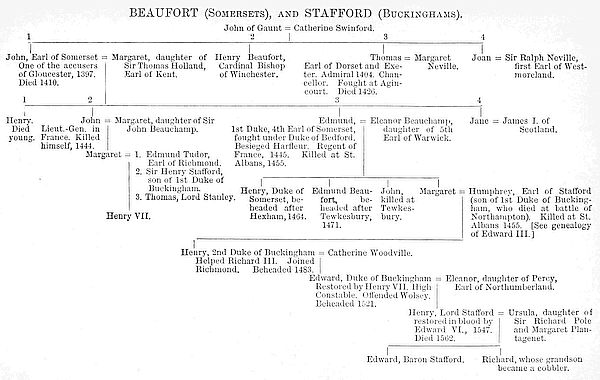

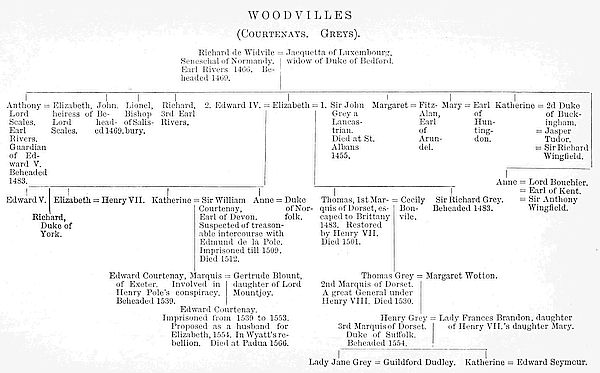

The Author has not scrupled to avail himself of the works of modern authors, though, in most cases, he has verified their views by reference to original authorities. In the earlier period the works of Professor Stubbs, Mr. Freeman, and Dr. Pauli; in the Tudor and Stuart period those of Froude, Ranke, and Macaulay; in the later period the histories of Miss Martineau and Lord Stanhope have been of the greatest assistance. Greater stress has been laid upon the later than the earlier periods, as is indeed obvious from the divisions of the work. With regard to the starting-point chosen, it may be well to explain that the English invasion was fixed upon, because it so thoroughly obliterated all remnants of the Roman rule, that they have exerted little or no influence upon the development of the nation—the real point of interest in a national history. It is hoped that the genealogies of the great families will assist in the comprehension of mediæval times in the history of which they played so large a part, and that the maps supplied will suffice to enable the reader to follow pretty accurately,[vii] without reference to another atlas, the military and political events mentioned. A brief and rapid summary for the use of beginners was originally projected to preface the work, but the brevity required by a book of this description rendered such an addition impossible without injury to the more important part. An attempt has been made to replace it by a very full analysis, which, in the hands of a careful teacher, has been proved by experience a useful method of teaching the main facts of history.

Oxford, 1875.

BEFORE THE CONQUEST.

General Histories.

Lappenberg’s England under the Anglo-Saxon Kings. Lingard’s History of England. Sharon Turner’s History of the Anglo-Saxons. Freeman and Palgrave have each published short books for the young on the period.

Constitutional.

All that is necessary to be known is to be found in Stubbs’ Constitutional History. Treated more at length in Kemble’s Saxons in England, and Sir F. Palgrave’s History of the English Commonwealth. An excellent sketch in Freeman’s Norman Conquest. All the ancient laws are collected in Thorpe’s Ancient Laws; sufficient extracts to be found in Stubbs’ Illustrative Documents. The whole history, including literature and society, is given in Green’s History of the English People in a brief and very interesting form.

General Authorities.

Bæda’s Ecclesiastical History, for a century and a half after the landing of Augustin. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which becomes very important after the time of Alfred. Milman’s Latin Christianity.

The English Conquest.

Gildas, and the earlier part of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Establishment of the Church.

Kemble’s Saxons. Stubbs’ Constitutional History.

Alfred.

Asser’s Life. Dr. Pauli’s Life.

Dunstan.

Stubbs’ Preface to Life of Dunstan (Master of the Rolls’ series). E. W. Robertson’s Essay on Dunstan.

Eadward the Confessor and Family of Godwine.

Lives of Eadward, edited by Luard (Rolls’ series). Freeman’s Norman Conquest, vol. ii.

Normandy.

Palgrave’s History of Normandy and England. Freeman’s Norman Conquest. William de Jumièges. Orderic Vitalis. William of Poitiers.

NORMAN AND PLANTAGENET KINGS.

General Histories.

Lingard. Lappenberg. Pearson’s Early and Middle Ages of England. Hook’s Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury. Campbell’s Lives of the Chancellors. Foss’s Judges of England.

Constitutional.

Stubbs’ Constitutional History and Illustrative Documents.

General Authorities.

Orderic Vitalis. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

William I.

Eadmer’s Historia Novorum. Domesday-Book with Ellis’ Introduction.

William II.

Palgrave’s William Rufus. Eadmer’s Life of Anselm. Church’s Life of Anselm.

Henry I.

William of Malmesbury. Henry of Huntingdon (Surtees Society).

Stephen.

Gesta Stephani (Surtees Society).

Henry II. and Becket.

Dr. Giles’ Collection of the Letters of Becket, Foliot, and John of Salisbury. Gervais of Canterbury till 1200 (Twisden’s Decem Scriptores). Benedict of Peterborough, 1169-1192, and Roger of Hoveden to 1201, with Stubbs’ Prefaces in the Rolls’ series. William of Newbury, to 1198 (English Historical Society). Lord Lyttleton’s Life of Henry II.

Ireland.

Geraldus Cambrensis’ Conquest of Ireland (Rolls’ series, translated in Bohn).

Richard I.

Itinerarium Regis Ricardi (Rolls’ series). Richard of Devizes (English Historical Society). Ralph of Diceto, 1200 (Twisden). Several chronicles are translated in Bohn as Chronicles of the Crusades.

John and the Great Charter.

Roger of Wendover, who was continued by Matthew of Paris, and William Rishanger (Rolls’ series). Chronicles of various abbeys, such as Waverley and Dunstable. For the English reader, Stubbs’ Illustrative Documents.

Henry III.

Matthew of Paris. Rishanger. The Royal Letters (edited by Shirley in the Rolls’ series). The Rhyming Chronicle of Robert of Gloucester to 1270. Blaauw’s Barons’ War. Wright’s Political Songs (Camden Society). Brewer’s Monumenta Franciscana (Rolls’ series).

LATER PLANTAGENETS.

General Histories.

Sharon Turner’s Middle Ages. Lingard. Dr. Pauli’s Geschichte von England. Hook’s Archbishops. Campbell’s Chancellors.

Constitutional.

Stubbs. Hallam.

General Authorities.

Rymer’s Fœdera. Public Documents published chiefly by the Record Commission. Various Rolls, especially Rolls of Parliament, Statutes of the Realm, Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council. Walter of Hemingburgh, to 1346. Thomas of Walsingham, a compilation from the Annals of St. Albans Abbey (Rolls’ series).

For Scotch History.

Hill Burton’s History of Scotland.

For French History.

Martin or Sismondi’s History.

Edward I.

Trivet (English Historical Society). Rishanger. Palgrave’s Documents and Records illustrating History of Scotland. Freeman’s Essay on Edward I. Modus tenendi Parliamentum (Stubbs’ Documents). Rotuli Scotiæ (Record Commission).

Towns.

Ordinances of the English Guilds (Early English Text Society), with Brentano’s Preface.

Edward II.

Trokelowe, to 1323 (Rolls’ series). Anonymous Monk of Malmesbury, to 1327. Thomas de la Moor (Camden Society). Adam of Murimuth (English Historical Society).

Edward III.

Froissart. John le Bel. Robert of Avesbury, to 1356 (Hearne). Knyghton (Twisden’s Decem Scriptores). Longman’s History of Edward III.

Wicliffe.

Shirley’s Preface to Fasciculi Zizaniorum. Vaughan’s Life of Wicliffe.

Black Death.

Seebohm’s Essays in the Fortnightly Review for 1865.

Condition of the People.

Rogers’ History of Prices.

Richard II.

Walsingham. Annales Ricardi Secundi et Henrici Quinti (Rolls’ series). Chronique de la Traison et Mort de Richard (English Historical Society). M. Wallon’s Richard II. is said to be the best modern book on the subject. Wright’s Political Songs (Rolls’ series).

HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK.

General Histories.

As before, with Brougham’s History of England under the House of Lancaster.

Old Histories.

Fabyan, died 1512 (edited by Sir Henry Ellis). Hall, Henry IV. to Henry VIII. Polydore Vergil (Camden Society). Stowe, published 1592. Ellis’ Collection of Original Letters illustrative of English History.

Henry IV.

Walsingham (Rolls’ series). Knyghton. Royal Historical Letters (Rolls’ series).

Henry V.

Walsingham. Memorials of Henry V. (Rolls’ series). Titus Livius Vita Henrici Quinti (copied in part in the Gesta). Gesta Henrici Quinti (Historical Society). Monstrelet.

Henry VI.

William of Worcester to 1491 (completed by his son). English Chronicle (Richard II. to 1471) (Camden Society). Continuator of Croyland, 1459-1485. John of Westhampstead (Hearne). Paston Letters, 1434-1485 (E. D. Gairdner). Memoir of John Carpenter. Wars of the English in France (Rolls’ series). Procès de Jeanne d’Arc (Historical Society of France).

Edward IV.

Arrival of Edward IV. (Camden Society). Warkworth, 1461-1474.

Edward V.

Life, by Sir Thomas More.

Richard III.

History, by Sir Thomas More. Miss Halsted’s Life. Letters of Richard III. and Henry VII. (Gairdner, Rolls’ series).

| ENGLAND BEFORE THE CONQUEST. 449-1066. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Departure of the Romans, | 1 | |

| Settlement of the various English tribes, | 1 | |

| 449 | The Jutes, | 1 |

| 477 | The Saxons, | 2 |

| 520 | The Angles, | 2 |

| 597 | Conversion to Christianity, | 3 |

| Struggle for supremacy among the Saxon kingdoms, | 3 | |

| Supremacy of Northumbria, | 3 | |

| 716-819 Supremacy of Mercia, | 4 | |

| 800 | Ecgberht, | 5 |

| Supremacy of the West Saxons, | 5 | |

| Period of Danish Invasion, | 5 | |

| 836 | Æthelwulf, | 6 |

| 858 | Æthelbald, | 6 |

| 860 | Æthelberht, | 6 |

| 866 | Æthelred, | 6 |

| 870 | Danish Conquest of East Anglia, | 7 |

| 871 | Alfred, | 7 |

| Appreciation of Alfred’s character, | 8 | |

| Continued superiority of Wessex, | 10 | |

| 901 | Eadward the Elder, | 10 |

| 925 | Æthelstan, | 11 |

| 940 | Eadmund, | 11 |

| 946 | Eadred, | 11 |

| Rise of Dunstan, | 12 | |

| 955 | Edwy, | 13 |

| 957 | Eadgar, | 13 |

| Dunstan’s government, | 13 | |

| Division of Northumbria, | 14 | |

| 975 | Eadward the Martyr, | 15 |

| Fall of Dunstan, | 15 | |

| 979 | Æthelred the Unready, | 15 |

| [xiv] Third Period of Danish Invasion, | 15 | |

| 991 | Battle of Maldon, | 16 |

| 994 | First Danegelt, | 16 |

| Æthelred’s Marriage with Emma, | 17 | |

| 1002 | Massacre of St. Brice, | 17 |

| Pernicious influence of Eadric Streona, | 17 | |

| 1008 | Thurkill’s invasion, | 17 |

| 1013 | Swegen’s Great Invasion, | 18 |

| England submits to Swegen, | 18 | |

| 1014 | Restoration of Æthelred, | 18 |

| 1016 | Edmund Ironside, | 19 |

| Five great battles, | 19 | |

| Division of the Kingdom, | 19 | |

| 1017 | Cnut King of all England, | 19 |

| His patriotic government, | 20 | |

| Disputed succession, | 21 | |

| Importance of Earl Godwine, | 21 | |

| 1037 | Harold, | 21 |

| 1040 | Harthacnut, | 21 |

| Restoration of the English Line, | 21 | |

| 1042 | Eadward the Confessor, | 21 |

| Rivalry of Godwine and the French Party, | 22 | |

| 1051 | Godwine banished, | 22 |

| 1052 | His return and death, | 23 |

| 1053 | Harold succeeds to his influence, | 23 |

| He subdues Wales, | 24 | |

| 1066 | Harold made King, | 24 |

| Claims of his rivals, Tostig and William of Normandy, | 24 | |

| William’s preparations, | 25 | |

| Tostig’s invasion, | 26 | |

| William lands, | 26 | |

| Battle of Hastings or Senlac, | 26 | |

| Death of Harold, | 27 | |

| —————————— | ||

| State of Society at the Conquest. | ||

| —————————— | ||

| THE CONQUEST. | ||

| WILLIAM I. 1066-1087. | ||

| 1066 | Intended resistance of the English, | 40 |

| Election of Eadgar, | 41 | |

| William marches to London, | 41 | |

| [xv] William is crowned, | 41 | |

| His position as King, | 42 | |

| Transfer of Property, | 43 | |

| The form of Law retained, | 43 | |

| Castles built, | 43 | |

| Appointment of Earls, | 43 | |

| 1067 | William revisits Normandy, | 44 |

| Misgovernment by his Viceroys, | 44 | |

| Consequent rebellion, | 44 | |

| Insurrections call him home, | 44 | |

| 1068 | His position in the North and West, | 45 |

| 1096 | His devastations in Yorkshire, | 47 |

| 1070 | Complete subjugation of the North, | 47 |

| William’s legislation, | 48 | |

| His reform of the Church, | 48 | |

| Appointment of foreign Bishops, | 48 | |

| Stigand deposed, | 48 | |

| Lanfranc Archbishop, | 49 | |

| His Legislation, | 49 | |

| He connects the Church with Rome, | 49 | |

| But William still Head of the Church, | 49 | |

| 1071 | Final Struggle of the English under Hereward, | 50 |

| Wales held in check by the Counts Palatine, | 51 | |

| Savage invasions from Scotland, | 51 | |

| 1072 | Malcolm swears fealty, | 52 |

| 1075 | Troubles in Normandy, | 52 |

| 1076 | Conspiracy of Norman nobles suppressed, | 52 |

| Waltheof executed, | 53 | |

| Quarrel between William and his Sons, | 53 | |

| 1079 | Reconciliation at Gerberoi, | 54 |

| Odo’s oppressive government, | 54 | |

| 1084 | Cnut’s threatened invasion, | 54 |

| 1085 | The Domesday Book, | 55 |

| 1087 | William’s death and burial, | 55 |

| CONQUEST OF NORMANDY AND ORGANIZATION OF ENGLAND. | ||

| WILLIAM II. 1087-1100. | ||

| 1087 | William crowned by Lanfranc, | 56 |

| Appeases the English, | 56 | |

| Checks Norman opposition, | 57 | |

| 1089 | Lanfranc dies, | 57 |

| Flambard succeeds him, | 57 | |

| 1090 | [xvi] William’s quarrels with his Brothers, | 57 |

| 1091 | War with Scotland, | 58 |

| 1094 | Continued War with Wales, | 59 |

| Troubles in Normandy, | 59 | |

| 1095 | Conspiracy of Mowbray, | 59 |

| 1100 | Size of his Dominions at his death, | 60 |

| Causes of his inferiority to his Father, | 60 | |

| 1089 | Disputes with the Church, | 61 |

| Bishoprics left vacant, | 61 | |

| 1093 | Anselm made Archbishop, | 61 |

| William opposes his reforms, | 62 | |

| HENRY I. 1100-1135. | ||

| 1100 | Henry secures the crown, | 63 |

| Conciliates all classes, | 63 | |

| His policy, | 64 | |

| His opponents, | 65 | |

| 1101 | Robert seeks the crown, | 65 |

| Withdraws without bloodshed, | 65 | |

| Henry attacks his partisans, | 65 | |

| 1102 | Defeat of Belesme and Norman Barons, | 66 |

| Establishment of royal power, | 66 | |

| Belesme received in Normandy, | 66 | |

| 1105 | Consequent invasion of the Duchy, | 66 |

| 1106 | Battle of Tenchebray, defeat of Robert, | 66 |

| 1107 | War with France, | 67 |

| Louis supports William Clito, | 67 | |

| End of the War, | 67 | |

| 1113 | Treaty of Gisors, | 67 |

| Prince William acknowledged heir, | 68 | |

| 1115 | Renewed War with France and Anjou, | 68 |

| 1119 | Battle of Brenneville, | 68 |

| Complete prosperity, | 68 | |

| 1120 | Death of Prince William, and its consequences, | 68 |

| 1124 | War with Anjou, | 69 |

| 1128 | Death of William Clito, | 69 |

| Attempt to secure the succession to Matilda, | 69 | |

| 1135 | Death of Henry, | 70 |

| Wales held in check by colonies of Flemings, | 70 | |

| Constant insurrections, | 70 | |

| Henry’s Church policy, | 70 | |

| 1100 | Anselm refuses fealty, | 71 |

| He has to leave England, | 71 | |

| 1106 | [xvii] Unsupported by the Pope, | 71 |

| Makes a compromise at Bec, | 71 | |

| 1102 | Synod of Westminster, | 71 |

| Frequent bad Church appointments, | 72 | |

| Henry corrects them when possible, | 72 | |

| Wretched condition of the People, | 72 | |

| Their chief complaints, | 73 | |

| Baronial tyranny, | 73 | |

| Heavy taxation, | 73 | |

| Henry cures what evils he can, | 74 | |

| His strict Police, | 74 | |

| Administrative machinery, | 74 | |

| Local Courts, | 75 | |

| Curia Regis, | 75 | |

| Its political effect, | 76 | |

| The National Assembly, | 76 | |

| FEUDAL OUTBREAK. | ||

| STEPHEN. 1135-1154. | ||

| 1135 | Strange character of the Reign, | 77 |

| Great power of the Church, | 78 | |

| Stephen’s Charter, | 78 | |

| Affairs in Wales, | 78 | |

| Early signs of disturbance, | 79 | |

| 1137 | War with Scotland, | 79 |

| Last national effort of the English, | 79 | |

| 1138 | Battle of the Standard, | 80 |

| Growth of Anarchy in England, | 80 | |

| Creation of Earldoms and castles, | 80 | |

| Robert of Gloucester renounces his fealty, | 81 | |

| Stephen’s mercenaries, | 81 | |

| Jealousy between the old and new Administrations, | 81 | |

| Stephen’s quarrel with the Church, | 82 | |

| 1139 | Consequent arrival of Matilda, | 82 |

| Civil War, | 82 | |

| Continued quarrel with the Church, | 82 | |

| 1141 | Robert of Gloucester, to bring matters to a crisis, fights the Battle of Lincoln, | 83 |

| Matilda seeks help from the Church and becomes Queen, | 83 | |

| Importance of the Londoners, | 83 | |

| Matilda offends both Church and Londoners, | 84 | |

| Consequent revolution of affairs, | 84 | |

| 1142 | [xviii] Gloucester taken prisoner and exchanged for Stephen, | 84 |

| 1146 | Renewal of the old anarchy, | 84 |

| 1147 | Appearance of Prince Henry, | 84 |

| 1148 | Death of Robert of Gloucester, | 85 |

| 1152 | Henry’s marriage and increased power, | 85 |

| The Church sides with him, | 85 | |

| 1153 | Meeting of the armies at Wallingford, | 85 |

| The Church mediates a Compromise, | 86 | |

| 1154 | Death of Stephen, | 86 |

| Quotations from Chroniclers showing the miseries of the Reign, | 86 | |

| RECONSTITUTION OF THE MONARCHY—FORMATION OF THE NATION. | ||

| HENRY II. 1154-1189. | ||

| 1154 | Main Objects of Henry’s Reign, | 89 |

| He restores order in the State, | 90 | |

| Friendship with Adrian IV., | 90 | |

| 1157 | Master of England, Henry attacks Wales, | 91 |

| Rise of Thomas à Becket, | 92 | |

| 1158 | He is employed in foreign negotiations, | 92 |

| 1159 | Nevertheless there is war with France, | 92 |

| Interesting points in it, | 92 | |

| The Scotch King serves Henry, | 93 | |

| Introduction of Scutage, | 93 | |

| Having reduced the State to order, Henry turns to the Church, | 93 | |

| General friendship of England and France with the Pope, | 94 | |

| 1161 | Election of Becket to Archbishopric, | 95 |

| He upholds the Encroachments of the Church, | 95 | |

| 1164 | Quarrel with Becket, and Constitutions of Clarendon, | 95 |

| Becket refuses them, | 96 | |

| Lukewarmness of Alexander III., | 96 | |

| The quarrel takes a legal form, | 97 | |

| Comes before the Council, | 97 | |

| Henry presses him with charges, | 97 | |

| Becket leaves the Court before judgment is given, | 98 | |

| 1165 | He is received by the Pope, | 98 |

| But Henry refuses to oppose Alexander, | 99 | |

| 1166 | Meanwhile he attacks Wales, and secures Brittany, | 99 |

| Becket excommunicates his enemies, | 99 | |

| 1167 | The Pope temporizes, | 99 |

| Critical position of Henry, | 100 | |

| 1170 | [xix] Coronation of young Henry, | 100 |

| Finding this step unpopular, | 101 | |

| Henry submits, | 101 | |

| Becket ventures to return to England, | 101 | |

| Becket’s death, | 101 | |

| Henry retires to the Invasion of Ireland, | 102 | |

| Condition of Ireland, | 102 | |

| 1169 | Invasion by Strongbow, | 102 |

| 1171 | Henry himself invades Ireland, | 102 |

| Irish Church adopts Romish discipline, | 102 | |

| Henry’s reconciliation with Rome, | 103 | |

| 1174 | Great Insurrection, | 103 |

| Crisis of the danger, | 104 | |

| Henry’s penance at Canterbury, | 104 | |

| Capture of the Scotch King at Alnwick, | 104 | |

| Henry’s complete success, | 105 | |

| Small diminution of Henry’s power, either temporal or ecclesiastical, | 105 | |

| Henry’s Judicial and Constitutional changes, | 106 | |

| The Curia Regis, | 106 | |

| Itinerant Justices, | 106 | |

| Origin of the Jury, | 108 | |

| Assize of Arms, Scutage, | 109 | |

| Closing troubles with his Sons and with France, | 109 | |

| The causes of these troubles, | 109 | |

| 1183 | First War, against Young Henry, | 110 |

| 1184 | Second War, against Richard, | 111 |

| 1187 | Third War, | 111 |

| 1188 | Saladin Tax, | 111 |

| 1189 | Last War, with Richard and Philip, | 112 |

| Henry’s ill success, | 112 | |

| Disastrous Peace and Death, | 112 | |

| Importance of the Reign, | 113 | |

| RICHARD I. 1189-1199. | ||

| 1189 | Persecution of the Jews, | 115 |

| All Offices put up for sale, | 116 | |

| 1190 | Richard starts for the Crusade, | 110 |

| Leaving England to Longchamp, | 116 | |

| Richard quarrels with Philip in Sicily, | 117 | |

| 1191 | He conquers Cyprus, | 118 |

| Miserable condition of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, | 119 | |

| 1187 | Jerusalem taken by Saladin, | 119 |

| 1189 | [xx] Acre besieged, | 119 |

| 1191 | Arrival of the Crusaders, | 119 |

| Richard saves Acre, | 120 | |

| Philip goes home, | 120 | |

| Richard quarrels with Austria, | 120 | |

| 1192 | Truce with Saladin, | 121 |

| 1191 | John’s Behaviour in England, | 121 |

| Return of Philip, | 122 | |

| Need of Richard’s return, | 122 | |

| 1192 | His imprisonment in Germany, | 122 |

| John and Philip combine against him, | 122 | |

| England ransoms him, | 123 | |

| 1194 | Richard’s return, John’s defeat, | 123 |

| War with France, | 123 | |

| 1199 | Richard’s death at Chaluz, | 124 |

| Development of the Administrative System, | 124 | |

| STRUGGLE BETWEEN THE CROWN AND THE NATION. | ||

| JOHN. 1199-1216. | ||

| 1199 | John secures the crown, | 126 |

| His strong position, | 127 | |

| 1200 | His danger from France, | 127 |

| Peace with Philip, and marriage treaty, | 127 | |

| Marriage with Isabella de la Marche, | 128 | |

| 1201 | Homage of Scotland, | 128 |

| Outbreak in Poitou, | 128 | |

| 1202 | John’s French Provinces forfeited, | 128 |

| 1203 | Death of Arthur, | 129 |

| 1205 | Loss of Normandy, | 129 |

| 1206 | Peace with Philip, | 129 |

| 1205 | Election of the Archbishop of Canterbury, | 130 |

| Stephen Langton, | 131 | |

| 1207 | Consecration at Viterbo, and John’s violence, | 131 |

| 1208 | Interdict and flight of Bishops, | 131 |

| 1209 | Excommunication, | 131 |

| 1210 | Attack on Scotland, Ireland and Wales, | 132 |

| Disaffection of the Northern Barons, | 133 | |

| The King’s rapacity, | 133 | |

| 1211 | European crisis, | 133 |

| League with Northern Princes, | 133 | |

| 1213 | John’s deposition, | 133 |

| Surrender of the Crown to the Pope, | 134 | |

| [xxi] John’s improved position, | 134 | |

| 1214 | Renewed difficulties with Stephen Langton, | 135 |

| 1215 | John hopes to secure his position by victory in France, | 135 |

| 1214 | Battle of Bouvines, | 136 |

| 1215 | Insurrection in England on his return, | 136 |

| Meeting at Brackley, | 136 | |

| Capture of London, | 137 | |

| Runnymede, | 137 | |

| Political position of England, | 137 | |

| Terms of Magna Charta, | 138 | |

| John attempts to break loose from it, | 139 | |

| 1216 | Louis is summoned, | 139 |

| John’s death, | 140 | |

| HENRY III. 1216-1272. | ||

| 1216 | Henry’s authority gradually established, | 141 |

| Difficulties at his accession, | 142 | |

| Pembroke’s measures of conciliation, | 142 | |

| 1217 | Fair of Lincoln, | 112 |

| Louis leaves England, | 142 | |

| Renewal of the Charter, | 142 | |

| 1218 | Papal attempt to govern by Legates, | 143 |

| Pandulf’s government, | 143 | |

| 1221 | His fall, | 143 |

| Triumph of national party under Hubert de Burgh, | 143 | |

| Parties in England, | 144 | |

| 1223 | Opposition Barons at Leicester, | 144 |

| Resumption of royal castles, | 145 | |

| 1224 | Destruction of Faukes de Breauté, | 145 |

| Danger from France, | 145 | |

| 1223 | Death of Philip, | 145 |

| 1226 | Death of Louis VIII., | 145 |

| English neglect this opportunity, | 146 | |

| Poitou remains French, | 146 | |

| 1227 | Hubert’s continued power, | 146 |

| Langton supports his policy, | 146 | |

| Change of Popes—increased exactions, | 147 | |

| 1228 | Death of Langton, | 147 |

| Quarrel of Henry and De Burgh, | 147 | |

| 1229 | Henry’s false foreign policy, | 147 |

| 1231 | Return of Des Roches, | 148 |

| 1232 | Twenge’s riots, | 148 |

| [xxii] Fall of De Burgh, | 148 | |

| 1233 | Revolution under Des Roches, | 149 |

| Earl of Pembroke upholds De Burgh, | 149 | |

| 1234 | Edmund of Canterbury causes Des Roches’ fall, | 150 |

| 1235 | Henry becomes his own minister, | 151 |

| 1236 | Henry’s marriage, | 151 |

| 1237 | Influence of the Queen’s uncles, | 151 |

| 1238 | Formation of a national party under Simon de Montfort, | 152 |

| Revival in the Church, | 152 | |

| Grostête, | 153 | |

| 1243 | Loss of Poitou, | 153 |

| Prince Richard joins the foreign party, | 154 | |

| 1244 | Exactions in Church and State, | 154 |

| 1247 | Inroad of Poitevin favourites, | 155 |

| 1248 | Discontent of the Barons, | 155 |

| Continued misgovernment, | 155 | |

| 1249 | Tallages on the cities, | 155 |

| 1250 | Diversion of the Crusade, | 156 |

| De Montfort’s government of Gascony, | 156 | |

| His quarrel with the King, | 156 | |

| 1253 | By his aid Gascony is saved, | 156 |

| The King’s money difficulties, | 157 | |

| 1254 | The Pope offers Edmund the Kingdom of Sicily, | 157 |

| Henry accepts it on ruinous terms, | 157 | |

| 1256 | Consequent exactions, | 158 |

| 1257 | Terrible famine, | 158 |

| Parliament at length roused to resistance, | 158 | |

| Parliament at Westminster, | 158 | |

| 1258 | The “Mad Parliament,” | 159 |

| Provisions of Oxford, | 159 | |

| Opposition to the surrender of Castles, | 160 | |

| Exile of aliens, | 160 | |

| Proclamation of the Provisions, | 160 | |

| Government of the Barons, | 160 | |

| 1259 | Final treaty with France, | 161 |

| Henry thinks of breaking the Provisions, | 161 | |

| 1261 | The Pope’s absolution arrives, | 161 |

| Quarrel between De Clare and De Montfort, | 161 | |

| 1262 | Return of De Montfort, | 162 |

| 1263 | Outbreak of hostilities, | 162 |

| 1264 | The Award of Amiens fails, | 163 |

| War—Battle of Lewes, | 163 | |

| The Mise of Lewes, | 163 | |

| Appointment of revolutionary government, | 163 | |

| The exiles assemble at Damme, | 164 | |

| [xxiii] De Montfort desires final settlement, | 164 | |

| Royalist movements on the Welsh Marches, | 164 | |

| 1265 | Parliament assembles, | 165 |

| Conditions of Prince Edward’s liberation, | 165 | |

| De Clare forsakes the Barons, | 166 | |

| He joins the Marchers, | 166 | |

| Escape of Edward, | 166 | |

| Leicester opposes Edward in Wales, | 166 | |

| Defeat at Kenilworth, | 166 | |

| Battle of Evesham, | 167 | |

| 1266 | Dictum of Kenilworth, | 168 |

| 1267 | De Clare compels more moderate government, | 168 |

| Constitutional end of the reign, | 168 | |

| Views of the people on the war, | 168 | |

| SETTLEMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION. | ||

| EDWARD I. 1272-1307. | ||

| 1272 | Edward’s accession and character, | 171 |

| The first English King, | 172 | |

| His political views, | 173 | |

| His legal mind, | 173 | |

| His success, | 173 | |

| His enforced concessions, | 174 | |

| 1275 | His first Parliament, | 174 |

| Statute of Westminster, | 174 | |

| Establishment of Customs, | 174 | |

| 1278 | Edward’s restorative measures, | 174 |

| New coinage, | 175 | |

| 1279 | Statute of Mortmain, | 175 |

| Affairs in Wales, | 175 | |

| 1275 | Llewellyn’s suspicious conduct, | 175 |

| 1277 | War breaks out, | 176 |

| Llewellyn submits, and is mercifully treated, | 176 | |

| 1282 | Second rising in Wales, | 176 |

| Death of Llewellyn, | 176 | |

| 1288 | Execution of David, | 176 |

| 1284 | Statute of Wales, | 177 |

| Annexation of Wales, | 177 | |

| 1282 | Foreign affairs call Edward abroad, | 177 |

| 1284 | The Sicilian Vespers, | 177 |

| 1286 | Edward acts as mediator between France and Aragon, | 178 |

| 1288 | [xxiv] His award is repudiated, | 178 |

| 1289 | Disturbances in England during his absence, | 178 |

| He returns, punishes corrupt judges, banishes the Jews, | 179 | |

| Second period of the reign, | 179 | |

| Relations with Scotland, | 180 | |

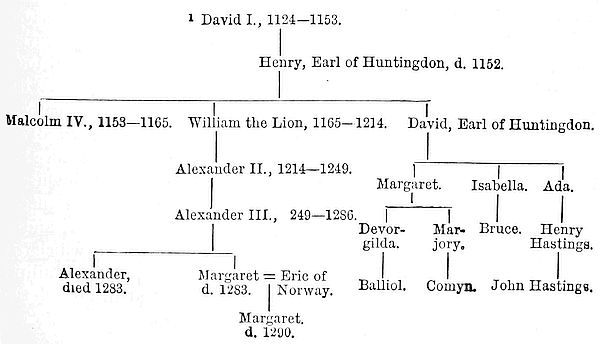

| 1290 | Extinction of the Scotch royal family, | 181 |

| Proposed marriage of the Maid and Prince Edward, | 181 | |

| Invitation to Edward to settle the Succession, | 182 | |

| Death of the Maid, | 182 | |

| 1291 | Meeting at Norham, | 182 |

| Edward’s supremacy allowed, | 182 | |

| The claimants to the Scotch throne, | 182 | |

| 1292 | Edward gives a just verdict, | 183 |

| Balliol accepts the throne as a vassal, | 183 | |

| 1293 | Scotland appeals therefore to the English Courts, | 183 |

| The appeals not pressed to extremities, | 184 | |

| Quarrel with France, | 184 | |

| Edward is outwitted, Gascony occupied, | 184 | |

| Balliol in alliance with France, | 184 | |

| 1295 | First True Parliament, | 183 |

| 1296 | Edward marches into Scotland, | 185 |

| Defeat of the Scotch at Dunbar, | 185 | |

| Submission of Balliol and Scotland, | 186 | |

| Constitutional opposition of Clergy and Barons, | 186 | |

| 1296 | Refusal of the Clergy to grant subsidies, | 186 |

| 1297 | The Clergy outlawed, | 187 |

| The Barons refuse to assist Edward, | 187 | |

| Compromise with the Clergy, | 187 | |

| Edward secures an illegal grant, | 187 | |

| The Earls demand the confirmation of the Charters, | 188 | |

| They are granted with reservations, | 188 | |

| Scotch insurrection under Wallace, | 189 | |

| 1299 | English Treaty with France, | 189 |

| Edward invades Scotland, | 190 | |

| Defeats Wallace at Falkirk, | 190 | |

| Comyn’s Regency, | 190 | |

| 1301 | Parliament of Lincoln, | 190 |

| The Pope’s claims rejected, | 191 | |

| 1303 | Third invasion and conquest of Scotland, | 191 |

| 1306 | Bruce murders Comyn and rebels, | 192 |

| Preparations for a fourth invasion, | 192 | |

| 1307 | Edward’s death near Carlisle, | 192 |

| Constitutional importance of the reign, | 193 | |

| RENEWAL OF THE STRUGGLE OF THE NATION AGAINST THE CROWN. | ||

| EDWARD II. 1307-1327. | ||

| 1307 | Edward’s friendship for Gaveston, | 198 |

| 1308 | The Barons demand his dismissal, | 198 |

| 1309 | Gaveston’s return, | 199 |

| General discontent, | 199 | |

| Statute of Stamford, | 200 | |

| 1310 | Appointment of the Lords Ordainers, | 200 |

| 1311 | Useless assault on Scotland, | 200 |

| The Ordinances published, | 201 | |

| Policy of the Opposition, | 201 | |

| Gaveston banished, | 201 | |

| 1312 | He reappears with the King, | 202 |

| He is beheaded at Warwick, | 202 | |

| 1314 | Renewal of the War with Scotland, | 203 |

| Battle of Bannockburn, | 203 | |

| Edward refuses to treat, | 204 | |

| Consequent disasters, | 204 | |

| 1315 | Wars in Wales and Ireland, | 204 |

| Bruce’s invasion of Ireland, | 204 | |

| 1316 | He is crowned King, | 205 |

| 1318 | He is killed at Dundalk, | 205 |

| 1316 | Distress in England, | 205 |

| Lancaster temporary Minister, | 205 | |

| Power of the Despensers, | 205 | |

| 1318 | Temporary reconciliation, | 206 |

| 1320 | Truce with Scotland, | 206 |

| The Welsh Marchers quarrel with the Despensers, | 206 | |

| Edward supports his favourites, | 206 | |

| 1321 | Hereford and Lancaster combine, | 206 |

| The Despensers are banished, | 206 | |

| An insult to the Queen rouses the King to energy, | 207 | |

| Edward recalls the Despensers, | 207 | |

| 1322 | Pacifies the Marches, | 207 |

| Attacks Lancaster, | 207 | |

| Battle of Boroughbridge, | 207 | |

| Lancaster worshipped as a Saint, | 207 | |

| Triumph of the Despensers, | 208 | |

| Renewal of war with Scotland, | 208 | |

| 1323 | Peace for thirteen years with Scotland, | 208 |

| Dangers surrounding the King, | 208 | |

| 1324 | Difficulties with France, | 209 |

| 1325 | [xxvi] The Queen and Prince in France, | 209 |

| 1326 | She lands in England, | 210 |

| Her party gathers strength, | 210 | |

| The King is taken, | 210 | |

| 1327 | The Prince of Wales made King, | 210 |

| Murder of Edward, | 211 | |

| BEGINNING OF HUNDRED YEARS’ WAR, AND CONSTITUTIONAL PROGRESS. | ||

| EDWARD III. 1327-1377. | ||

| 1327 | Measures of reform, | 214 |

| Mortimer’s misgovernment, | 214 | |

| Fruitless campaign against Scotland, | 214 | |

| Opposition to Mortimer, | 214 | |

| 1330 | Conspiracy and death of Kent, | 215 |

| Edward overthrows Mortimer, | 215 | |

| Edward’s healing measures, | 216 | |

| 1332 | Balliol invades Scotland, | 216 |

| Edward supports him, | 216 | |

| Siege of Berwick, | 217 | |

| 1333 | Battle of Halidon Hill, | 217 |

| 1334 | Temporary Submission of Scotland, | 217 |

| Edward’s claims on France, | 218 | |

| The Scotch, with Philip’s help, renew the War, | 218 | |

| 1337 | Edward therefore produces his claims, | 218 |

| Edward attacks France, | 218 | |

| 1338 | His alliances on the North-east, | 219 |

| He is made Imperial Vicar, | 219 | |

| Great taxation, | 219 | |

| He lands in Flanders, | 220 | |

| 1339 | Deserted by his allies, he returns home, | 220 |

| 1340 | Returns, and wins the Battle of Sluys, | 220 |

| Fruitless expedition to Tournay, | 220 | |

| Sudden visit to England, | 221 | |

| Displacement of the Ministry, | 221 | |

| 1341 | His dispute with Stratford, | 221 |

| Edward yields, | 221 | |

| 1342 | Loss of all his allies, | 222 |

| New opening in Brittany, | 222 | |

| 1343 | Mediation of the Pope offered, | 223 |

| Decay of Papal influence, | 223 | |

| 1344 | [xxvii] His mediation accepted conditionally, it fails, | 224 |

| Edward’s commercial difficulties, | 224 | |

| 1345 | War breaks out again, | 224 |

| Derby hard pressed in Guienne, | 224 | |

| 1346 | Edward, to relieve him, lands in Normandy, | 225 |

| Marches towards Calais, | 225 | |

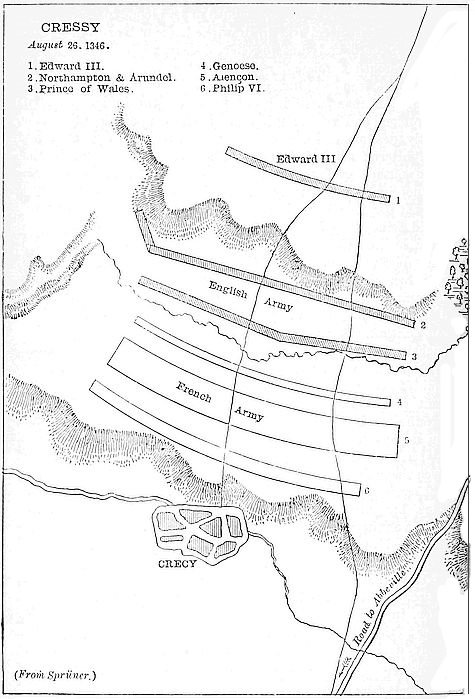

| Battle of Cressy, | 227 | |

| Battle of Neville’s Cross, | 228 | |

| 1347 | Siege of Calais, | 228 |

| Truce, | 229 | |

| 1349 | The Black Death, | 229 |

| 1355 | Renewal of the War, | 229 |

| Destructive March of the Black Prince southwards, | 229 | |

| The “Burnt Candlemas,” | 231 | |

| 1356 | The Black Prince’s expedition northwards, | 231 |

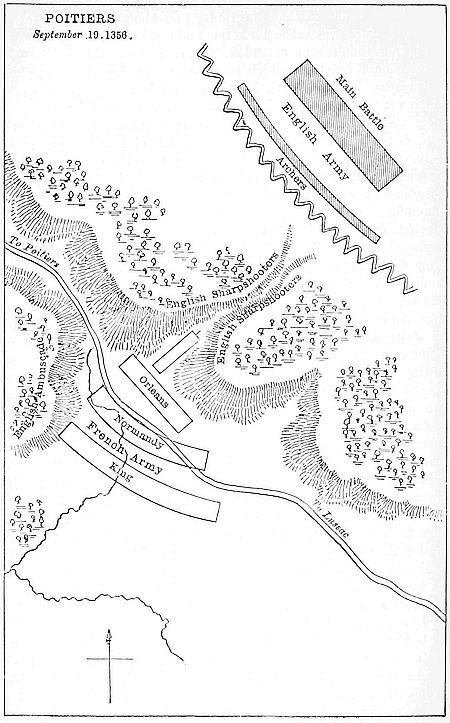

| Battle of Poitiers, | 231 | |

| Release of King David, | 232 | |

| 1357 | Peace with Scotland, | 232 |

| Terrible condition of France, | 232 | |

| 1359 | Reviving power of the Dauphin, | 232 |

| Edward again invades France, | 233 | |

| 1360 | Want of permanent results induce Edward to make The Peace of Brétigny, | 233 |

| The Treaty is not carried out, | 234 | |

| 1364 | The War in Brittany continues, | 234 |

| 1365 | Affairs of Castile, | 234 |

| 1366 | France and England support the rival claimants, | 234 |

| 1367 | Battle of Navarette, | 235 |

| 1368 | Taxation in Aquitaine, | 235 |

| The Barons appeal to Charles, | 235 | |

| 1369 | Renewal of French War, | 235 |

| Gradual Defeat of the English, | 236 | |

| 1370 | The Black Prince takes Limoges, | 236 |

| His final return to England, | 236 | |

| 1374 | Loss of Aquitaine, | 236 |

| 1372 | Naval victory of the Spaniards, | 236 |

| 1375 | Discontent in England, | 236 |

| Politics of the Time, | 237 | |

| 1376 | The Good Parliament, | 239 |

| Death of the Black Prince, | 240 | |

| Lancaster regains power, | 240 | |

| 1377 | The Lancastrian Parliament, | 240 |

| Trial of Wicliffe, | 240 | |

| Uproar in London, | 240 | |

| Death of the King, | 240 | |

| BEGINNING OF THE FACTION FIGHT AMONG THE NOBILITY. | ||

| RICHARD II. 1377-1399. | ||

| 1377 | Difficulties of the new reign, | 242 |

| Regency and administration of Lancaster, | 242 | |

| Patriotic government, | 243 | |

| 1380 | Money wanted for the War in Brittany, | 243 |

| The Poll Tax, | 243 | |

| 1381 | Insurrection of the Villeins, | 244 |

| Death of Wat Tyler, | 244 | |

| The insurrection suppressed, | 245 | |

| Parliament rejects the Villeins’ claims, | 245 | |

| 1383 | Suspicions of Lancaster’s objects, | 245 |

| He deserts Wicliffe, | 245 | |

| He is charged with the failure in Flanders, | 246 | |

| 1385 | Jealousy of him thwarts the Scotch invasion, | 246 |

| He is glad of the excuse to leave England to support his claims in Castile, | 246 | |

| Gloucester takes Lancaster’s place, | 246 | |

| The King’s Favourites, | 247 | |

| 1386 | Gloucester heads an opposition, | 247 |

| Change of Ministry demanded, | 247 | |

| Impeachment of Suffolk, | 247 | |

| Commission of Government, | 247 | |

| 1387 | The King prepares a counterblow, | 248 |

| The Five Lords Appellant, | 248 | |

| They impeach the King’s friends, | 248 | |

| Affair of Radcot, | 248 | |

| 1388 | The Wonderful Parliament, | 248 |

| 1389 | Gloucester’s unimportant Government, | 249 |

| Richard assumes authority, | 249 | |

| 1393 | Final Statute of Provisors, | 250 |

| 1394 | Expedition to Ireland, | 250 |

| 1397 | Marriage with Isabella of France, | 251 |

| Richard’s vengeance after seven years’ peace, | 251 | |

| 1398 | Hereford and Norfolk banished, | 252 |

| His arbitrary rule alienates the people, | 253 | |

| 1399 | During his absence in Ireland, | 253 |

| Hereford returns and is triumphantly received, | 253 | |

| He captures Richard, | 254 | |

| Makes him resign the Kingdom, | 254 | |

| ——————— | ||

| State of Society. | ||

| ——————— | ||

| MONARCHY BY PARLIAMENTARY TITLE. | ||

| HENRY IV. 1399-1413. | ||

| 1399 | Henry’s position in English History, | 275 |

| Reversal of the Acts of the late King, | 276 | |

| Tumultuous scene in the First Parliament, | 276 | |

| The King’s insecure position for nine years, | 276 | |

| 1400 | Insurrection of the late Lords Appellant, | 277 |

| Imprisonment and secret death of Richard, | 277 | |

| Hostile attitude of France and Scotland, | 278 | |

| Useless and impolitic march into Scotland, | 278 | |

| 1401 | Insurrection Wales, | 278 |

| Owen Glendower, | 278 | |

| 1402 | Quarrel with the Percies, | 278 |

| The pretended Richard, | 279 | |

| Causes of the quarrel with Northumberland, | 279 | |

| 1403 | The Percies combine with Glendower, | 279 |

| Battle of Shrewsbury, | 280 | |

| 1404 | Submission of Northumberland, | 280 |

| Widespread Conspiracy, | 280 | |

| 1405 | Flight of the young Earl of March, | 280 |

| Renewed activity of Northumberland, Scrope and Mowbray, | 281 | |

| Events which secured Henry’s triumph, | 281 | |

| Capture of James of Scotland, | 281 | |

| 1407 | Murder of Orleans, | 282 |

| 1408 | Final defeat and death of Northumberland, | 282 |

| Henry’s improved position, | 282 | |

| His enforced respect for the Commons, | 282 | |

| Climax of their power, | 283 | |

| Explained by the King’s failing health, | 283 | |

| 1412 | Renewed vigour at the end of his reign, | 283 |

| Henry’s foreign policy, | 283 | |

| His alliance with the Church, | 284 | |

| His persecuting Statute, | 285 | |

| Views of the nation with regard to the Church, | 285 | |

| Henry’s jealousy of the Prince of Wales, | 285 | |

| RENEWAL OF THE HUNDRED YEARS’ WAR. | ||

| HENRY V. 1413-1422. | ||

| 1413 | Fortunate opening of his reign, | 287 |

| General amnesty and release of prisoners, | 288 | |

| 1414 | [xxx] Signs of slumbering discontent, | 288 |

| The Lollards, | 288 | |

| Henry’s reason for the impolitic French War, | 289 | |

| State of France, | 290 | |

| Expulsion of the Burgundians from Paris, | 290 | |

| Attempt at national government, | 290 | |

| Henry’s double diplomacy and outrageous claims, | 291 | |

| His preparations, | 291 | |

| 1415 | He lands in France, | 292 |

| Conspiracy of Cambridge, | 292 | |

| Capture of Harfleur, | 292 | |

| Henry compelled to retire upon Calais, | 293 | |

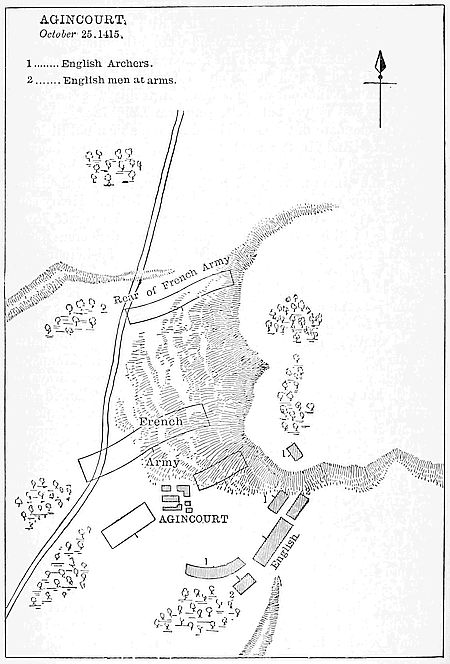

| Battle of Agincourt, | 295 | |

| The French Government falls into the hands of the Armagnacs, | 296 | |

| 1416 | Visit of Sigismund, | 297 |

| His position in Europe, | 297 | |

| His close union with Henry, | 297 | |

| Failure of his mediation, | 298 | |

| 1417 | Armagnac attacks Queen Isabella, | 298 |

| She allies herself with Burgundy, | 298 | |

| Henry’s second Invasion, | 298 | |

| 1418 | The Parisians, anxious for peace, admit the Burgundians, | 298 |

| 1419 | Fall of Rouen, | 299 |

| Negotiations for peace, | 300 | |

| Attempted reconciliation of the French parties, | 300 | |

| Murder of Burgundy, | 300 | |

| Young Burgundy joins England, | 300 | |

| 1420 | Treaty of Troyes, | 300 |

| 1421 | English defeat at Beaugé, | 301 |

| Henry hurries to Paris, | 301 | |

| 1422 | While re-establishing his affairs he dies, | 301 |

| Death of Charles VI., | 302 | |

| LOSS OF FRANCE AND DESTRUCTION OF THE BARONAGE. | ||

| HENRY VI. 1422-1461. | ||

| 1422 | Arrangements of the Kingdom, | 303 |

| Position of affairs in France, | 304 | |

| 1423 | Bedford’s marriage, | 304 |

| Release of the Scotch King, | 304 | |

| 1424 | Battle of Verneuil, | 305 |

| Consequent strength of the English position in France, | 305 | |

| [xxxi] It is disturbed by the consequences of Gloucester’s marriage, | 305 | |

| The first blow to the Burgundian alliance, | 305 | |

| 1425 | Rivalry of Beaufort and Gloucester, | 306 |

| 1426 | Gloucester’s marriage with Eleanor Cobham, | 307 |

| Bedford again secures Burgundy, | 307 | |

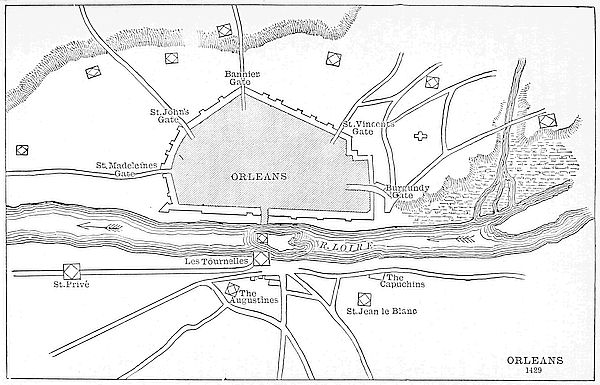

| 1428 | And attacks Orleans, | 307 |

| 1429 | Battle of the Herrings, | 308 |

| Danger of Orleans, | 308 | |

| Joan of Arc, | 308 | |

| Causes of her success, | 310 | |

| The siege is raised, | 310 | |

| March to Rheims to crown the Dauphin, | 310 | |

| Unsuccessful attack on Paris, | 311 | |

| 1430 | Capture of Joan of Arc, | 311 |

| Coronation of King Henry, | 311 | |

| 1431 | Joan’s death, | 311 |

| 1432 | Increasing difficulties of the English, | 312 |

| State of England, | 312 | |

| Conduct of Gloucester, | 312 | |

| Death of the Duchess of Bedford, | 312 | |

| Bedford re-marries. Second blow to the Burgundian alliance, | 312 | |

| 1433 | Efforts at peace, and | 313 |

| 1434 | Rise of a War party under Gloucester, | 313 |

| 1435 | Great Peace Congress at Arras, | 314 |

| Bedford’s death, | 314 | |

| Consequent defection of Burgundy, | 314 | |

| 1436 | Obstinacy of the War party, | 314 |

| Continued ill success, | 315 | |

| Danger from Scotland, | 315 | |

| 1437 | James’s death, | 315 |

| 1440 | Peace party procures the liberation of Orleans, | 316 |

| 1442 | Peace becomes necessary, | 316 |

| Rise of Suffolk, | 316 | |

| 1445 | Marriage of Henry with Margaret of Anjou, | 316 |

| 1446 | Pre-eminence of Suffolk, | 317 |

| 1447 | Gloucester’s death, | 317 |

| York takes his place, | 317 | |

| 1448 | Ministry of Suffolk, | 318 |

| His unpopularity, | 318 | |

| Renewal of the War, | 318 | |

| 1449 | Fall of Rouen, | 319 |

| Popular outbreak against Suffolk, | 319 | |

| 1450 | Murder of Suffolk, | 319 |

| Continued discontent, | 320 | |

| [xxxii] Jack Cade, | 320 | |

| 1452 | York’s appearance in arms; Civil War begins, | 320 |

| He is duped into submission, | 321 | |

| 1453 | Imbecility of the King, | 321 |

| 1454 | Prince of Wales born, | 321 |

| York’s First Protectorate, | 322 | |

| Recovery of the King, | 322 | |

| 1455 | York again appears in arms, | 322 |

| First Battle of St. Albans, | 322 | |

| Character of the two parties, | 323 | |

| 1456 | York’s Second Protectorate, | 324 |

| 1457 | With the Nevilles he retires from Court, | 324 |

| 1458 | Hollow reconciliation of parties, | 325 |

| 1459 | Renewed hostilities, | 325 |

| Battle of Blore Heath, | 325 | |

| Flight of the Yorkists from Ludlow, | 325 | |

| Lancastrian Parliament at Coventry, | 325 | |

| 1460 | Fresh attack of the Yorkists, | 325 |

| Battle of Northampton, | 326 | |

| Yorkist Parliament in London, | 326 | |

| York at last advances claims to the throne, | 326 | |

| The Lords agree on a compromise, | 326 | |

| York is defeated and killed at Wakefield, | 326 | |

| 1461 | The young Duke of York wins the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross, | 327 |

| The Queen, advancing to London, wins second Battle of St. Albans, | 327 | |

| Sudden rising of the Home Counties, | 327 | |

| Triumphant entry of Edward, | 327 | |

| HEREDITARY ROYALTY WITHOUT CONSTITUTIONAL CHECKS. | ||

| EDWARD IV. 1461-1483. | ||

| 1461 | Edward secures the crown, | 328 |

| Battle of Towton, | 328 | |

| Yorkist Parliament, | 328 | |

| 1462 | With French help Margaret keeps up the War, | 328 |

| 1464 | Battle of Hedgeley Moor, | 328 |

| Battle of Hexham, | 328 | |

| 1465 | Edward’s triumph and popular Government, | 329 |

| Apparent security of his Throne, | 330 | |

| Destroyed by his marriage, and the rise of the Woodvilles, | 330 | |

| 1466 | [xxxiii] Power of the Nevilles, | 331 |

| Their French policy, | 331 | |

| Edward’s Burgundian policy, | 331 | |

| 1467 | Defection of the Nevilles, | 332 |

| 1469 | Popular risings inspired by them, | 332 |

| Clarence’s weakness drives them to the Lancastrians, | 333 | |

| 1470 | Wells’ rebellion, | 333 |

| Flight of Warwick, | 333 | |

| He returns and re-crowns Henry, | 334 | |

| 1471 | Edward gets help from Burgundy, | 334 |

| Clarence joins him, | 335 | |

| Battle of Barnet, | 335 | |

| Margaret lands in England, | 335 | |

| Battle of Tewkesbury, | 335 | |

| Edward’s triumphant return to power, | 335 | |

| Murder of Henry, | 335 | |

| Clarence’s quarrels, | 336 | |

| 1476 | With Richard, | 336 |

| 1477 | With Edward, | 336 |

| 1478 | His trial and death, | 337 |

| 1475 | Edward joins Burgundy against France, | 337 |

| Failure of his expedition, | 337 | |

| Treaty of Pecquigni, | 338 | |

| Ambitious projects of marriage for his daughters, | 338 | |

| 1482 | Affairs in Scotland, | 338 |

| Edward supports Albany, | 339 | |

| He gains Berwick, | 339 | |

| 1483 | His death and character, | 339 |

| EDWARD V. 1483. | ||

| 1483 | State of parties at Edward IV.’s death, | 340 |

| Richard overthrows the Queen’s party, | 340 | |

| He is made Protector, | 340 | |

| He quarrels with the new nobles, | 340 | |

| Hastings’ death, and fall of his party, | 341 | |

| Richard, with Buckingham’s help, secures the crown, | 341 | |

| RICHARD III. 1483-1485. | ||

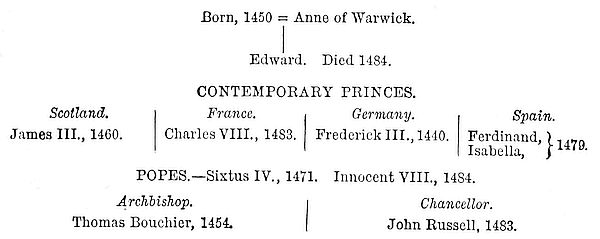

| 1483 | Richard’s position, and policy of conciliation, | 345 |

| His strong position, | 345 | |

| [xxxiv] Weak points in it, | 346 | |

| Disaffection in the South, | 346 | |

| Death of the Princes, | 346 | |

| Projected marriage of Elizabeth and Richmond, | 346 | |

| Defection of Buckingham, | 347 | |

| Richmond’s first Invasion, | 347 | |

| Death of Buckingham, | 347 | |

| Failure of the Conspiracy, | 347 | |

| 1484 | The great Act of Confiscation, | 347 |

| Richmond’s continued schemes, | 348 | |

| Richard’s efforts to oppose him, | 348 | |

| Attempts to win the Queen, | 348 | |

| Death of the Prince of Wales, | 348 | |

| Lincoln declared heir, | 348 | |

| 1485 | General uneasiness in England, | 348 |

| Richard has recourse to benevolences, | 349 | |

| Richmond lands at Milford, | 349 | |

| Conduct of the Stanleys, | 349 | |

| Battle of Bosworth, | 349 | |

| Richard’s character and laws, | 350 | |

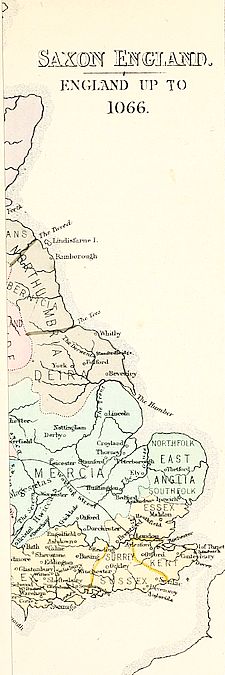

| 1. SAXON ENGLAND | At end of Book |

| 2. CRUSADES | ” ” |

| 3. FRANCE | ” ” |

| 4. ENGLISH POSSESSIONS IN FRANCE | ” ” |

| 5. NORTH OF FRANCE | ” ” |

| 6. ENGLAND AND WALES | ” ” |

The history of civilization can be traced in great lines which have more or less followed a similar direction throughout all Europe. The interest of a national history is to observe the course which these lines have followed in a particular instance; for, examined in detail, their course has never been identical. The period occupied by what we speak of as English history is that, speaking broadly, during which the great mediæval systems—feudalism and the Church—have by degrees given place to modern society, of which the moving-springs are freedom of the individual, government in accordance with the popular will, and freedom of thought. The object of a History of England is therefore to trace that change as it worked itself out amid all the various influences which affected it in our own nation. The peculiar circumstances of the Norman conquest prevented the complete development in England of either of the great Continental systems. Neither the feudal system nor the system of the Roman Church are to be found in their completeness in England. The separation of England from the Empire, the entire destruction of the Roman occupation by the German invaders, prevented that contact between German and Roman civilization from which Continental feudalism sprang. And though, if left to itself, the civilization of the early English would have ripened into some form of feudalism, it was caught by the Conquest before the process was completed. The Normans brought with them, indeed, the external apparatus of the completed system; but in the hands of their great leader, and grafted upon the existing institutions of the country, it assumed a new form. The power of the King was always maintained and the power of the barons suppressed, while room was left under the shadow of a strong monarchy for the growth of the lower classes of the nation. In the[xxxvi] same way, the Church was always kept from assuming a position of supremacy, and its subordinate relations to the State maintained. The establishment of this new form of government may be held to occupy the first period of our history since the Conquest, lasting till the reign of John. During that time the barons, who had more than once attempted to establish the same virtual independence as was enjoyed by their fellows abroad, were taught to recognize the power of the Crown. The legislation of Henry I. and Henry II., and the establishment under the latter of a new nobility dependent for their status upon their ministerial services, coupled with the incorporation of the national system of justice with the feudal system of the conquerors, united all classes of Englishmen and consolidated the nation, but in so doing raised to an alarming degree the power of the Crown. The miserable reign of John, and the tyrannical use he made of the power thus placed in his hands, called attention to the dangers which beset the administrative arrangements of his father. The total severance of England from France, which took place in his reign, and his rash quarrel with the Church, completed the work of national consolidation, but placed the united nation in antagonism to the throne. The nobility, which in other countries were the natural enemies of all classes below them, were thus forced to assume the lead of all who desired a reasonable amount of national freedom.

The struggle to harmonize the relations which should exist between the Crown and the subject occupies the second period of our history. It assumes several forms; sometimes the dislike of foreigners, sometimes a desire for self-taxation, sometimes it seems little more than an outbreak of an over-strong nobility. But whatever its form, the fruits of the struggle were lasting. The rival claims of King and nation, acknowledged and regulated by the wisdom of Edward I., gave rise to that balanced constitution which in its latest development still exists among us. But it would seem that this great advance in government had been somewhat premature. In other nations institutions resembling our Parliament sprang into existence, and faded away before the power of the Crown, an effect which can be traced chiefly to the strong line of division separating the commonalty from the nobles. Without support from the nobility, and in all its interests in direct antagonism to it, the commonalty, after supporting the Crown in the destruction of the baronage, found itself in presence of a power to which it was unable to offer any resistance. Several causes already mentioned had in England weakened the sharp definition of classes, but there was a great risk[xxxvii] even there of a similar failure of constitutional monarchy. It was as the leader of the nobility that Henry IV. first rose into importance in the reign of Richard II., and subsequently obtained the crown. The limitation of the franchise in the reign of Henry VI., and the consequent subserviency of Parliament, were steps towards the elevation of an aristocratical influence, which, had it grown till its suppression by the Crown was rendered necessary, would have reproduced in England the historical phenomena visible in France. Fortunately the nobility were not at one among themselves. The various sources from which they derived their origin, the close family connections, and personal interests, split them into factions, which, taking advantage of a disputed succession, brought their quarrel to the trial of the sword with such animosity that the nobility of England was virtually extinguished.

But while this faction fight, and the great French war which preceded it, attract the attention chiefly during the third period of the history, a quiet advance of great importance had been going on, sheltered by the more obvious movements of the time. The same spirit which had found its expression in the establishment of the Constitution, had indirectly, if not directly, influenced every class of the nation. The exclusive merchant guild had given place to the craftsman’s guild. The wars in France, the alienation of property fostered by the legislation of Edward I., the Black Death, which had robbed the country of at least a third of its labouring hands, had sealed the fate of serfdom, and established in England the great class of free wage labourers. The same alienation, the gradual increase and importance of trade, and the formation and introduction of capital, had formed a middle class of gentry, from which the successful merchant was not excluded. Nor had this political growth been unaccompanied by an advance of thought. The failure of the crusades, the last great exhibition of material religion; the Franciscan revival; the philosophy of Bacon and his successors; the bold declaration of independence on the part of Wicliffe, and the grasping and repellent character of the Roman Court, had shaken the Church to its foundations. The storm which had shaken the surface of English society had left its depths unmoved and undisturbed by the great work of extermination proceeding overhead; these processes of growth had been gradually continuing their course during the whole of the third period. Thus, then, when Edward IV. emerged from the troubles of the Wars of the Roses as King of England, his position, though it might[xxxviii] seem very similar to that of a king who had triumphed over his nobility, was yet considerably modified. The nobility were no doubt gone, but it was not the Crown which had crushed them. The Church, indeed, threw all its influence on the side of the Crown, but it was in the consciousness of the insecurity of its position in the hearts of the people that it did so. The King and his Commons stood face to face, with no intermediate class to check their mutual action, but the Commons were already free, and headed by a rapidly rising body of wealthy secondary landowners or merchants. Nevertheless, the immediate effect of the destruction of the nobility was completely to check constitutional growth, and to establish a government which was little short of arbitrary.

The Italian statecraft, which the influence of the Renaissance rendered paramount, for the moment increased the tendency to absolutism; and in the reign of Henry VIII., though a shadow of popular government yet remained, the will of the king was little short of absolute. What may be called the fourth period of our history is occupied by the establishment of this arbitrary power, and the gradual awakening of national life, under the influences of the Renaissance, and of the circumstances which accompanied the Reformation, which tended to modify it in the reign of Elizabeth. When Protestantism and the vigorous young thought of the reawakened nation became linked indissolubly with the fortunes of the sovereign in her national war against Spain, the mere necessity of the union tended much to put a practical limit to the arbitrary character of the new monarchy. It was the miscomprehension of the necessity of this union between king and people which produced the contests which occupy our history during the reign of the Stuarts.

Bred in the theory of monarchy by Divine right, the logical offspring of feudalism, when separated from the Empire and the Church, the Stuarts were willing to accept the arbitrary power of their predecessors, but would not acknowledge the necessity of harmonious action with the people, on which alone, as things then were, such arbitrary authority could rest. The middle class of gentry had been increasing in power and influence till they were now in a position to assume that leadership in the nation which the destruction of the nobles had left vacant. And behind them there was the bulk of the people, whose Protestantism, the religious character of the late national struggle, and the love of truth engendered by the Renaissance, had raised to enthusiastic Puritanism.[xxxix] The constitutional life, checked for a time by the Tudor monarchy, again sprang into existence. In the struggle which ensued it was the enthusiastic party which ultimately triumphed, and its leader, Cromwell, is seen mingling his conscientious efforts at the establishment of constitutional government with a religious fervour too great to be sustained.

But his rule, freed from those parts for which, as yet, the gentry at all events were unprepared, established, definitely and for ever, the necessity of recurring sooner or later to the constitutional principles of the fourteenth century. In the Revolution of 1688 those principles triumphed. But they triumphed in the hands no longer of a great enthusiastic leader, but of a party, which found its chief supporters in a limited number of noble houses, whose aristocratic pride was injured by the arbitrary power of the sovereign, and whose influence in the formation of Parliament promised them political superiority under the establishment of parliamentary government. From that time till the present the scene of the contest has been changed. A party struggle of some thirty years gave place to the unchecked predominance of parliamentary rule. And the last period of our history has been occupied by the efforts of the excluded nation to make their voice heard above that of a nominal representation, consisting in reality of the representatives of a dominant class, under the influence either of the great Whig families or of the Crown.

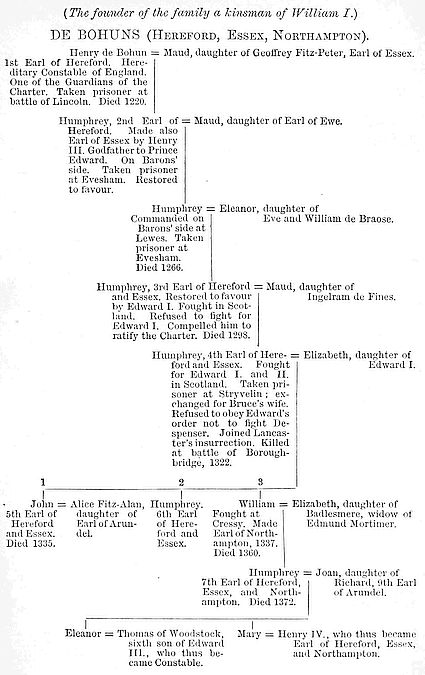

(The founder of the family a kinsman of William I.)

DE BOHUNS (Hereford, Essex, Northampton).

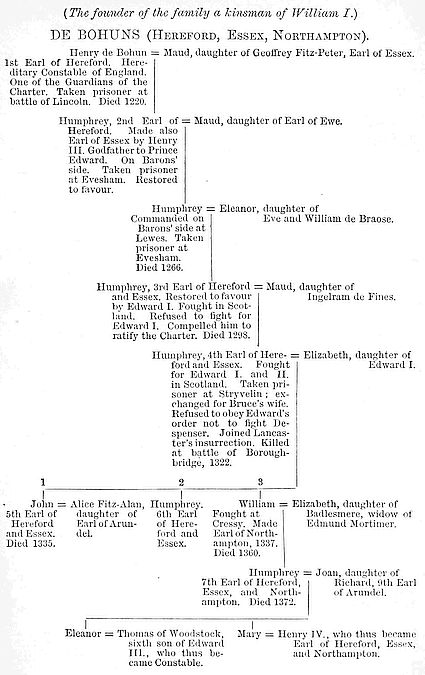

(Family founded at the Conquest.)

BEAUCHAMP

(Warwick).

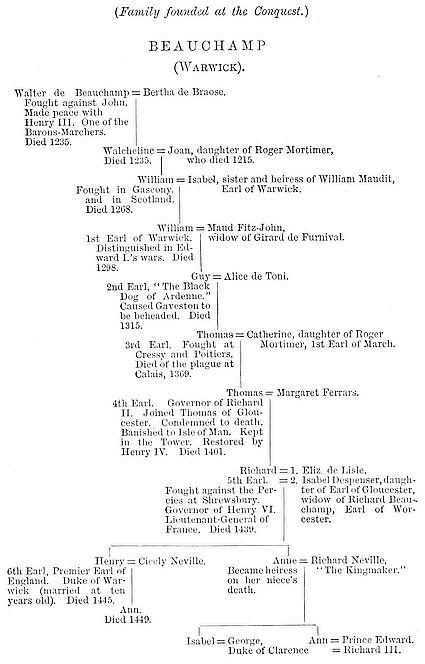

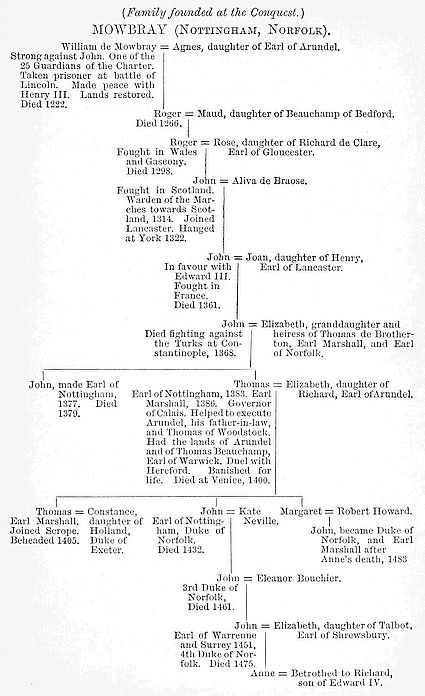

(Family founded at the Conquest.)

MOWBRAY (Nottingham, Norfolk).

MORTIMERS (March).

(Family founded at the Conquest.)

NEVILLES (Westmoreland, Warwick).

MARSHALLS AND BIGODS.

(Family founded at the Conquest.)

FITZ-ALAN (Arundel).

(Family founded in Henry I.’s reign.)

DESPENSERS.

LANCASTERS.

DE LA POLES.

BEAUFORT (Somersets), and STAFFORD (Buckinghams).

WOODVILLES

(Courtenays. Greys.)

The dominion of the Romans in Britain had been complete. The country, as far as the Frith of Forth, had been brought under Roman civilization. But in England, as elsewhere, the continuance of that form of civilization had produced weakness; and the unconquered Britons of the North, known by the name of Picts, broke into the Romanized districts, and pushed their incursions far into the centre of the country. On all sides, the nations outside the Empire were breaking through its limits and threatening its existence. The danger which threatened the very heart of the Empire, from the advance of the Goths into Italy, compelled the Romans in 411 to withdraw their legions from Britain, and leave the inhabitants of the island to fight their own battles with the Picts. When these enemies formed an alliance with the pirates of Ireland, known by the name of the Scots, and with the German pirates of the North Sea, known as English or Saxons, the civilized Britons were unable to make head against them, and found it necessary to seek for aid among the invaders themselves They therefore made an arrangement with two Jutish chiefs or Ealdormen, Hengist and Horsa, to come to their assistance. The German rovers consisted of three nations—the Saxons, the inhabitants of Holstein, who had advanced along the coast of Friesland; to the north of them the Angles or English, who inhabited Sleswig; and still further to the north, the Jutes, whose name is still perpetuated in the promontory of Jutland.

The first landing-place of the Jutish allies of the Britons was in the Isle of Thanet, separated at that time by a considerable inlet from the British mainland. Their aid enabled the Britons to drive back the Pictish invaders. But their success, and the settlement they had formed, enticed many[2] of their brethren to join them, and their numbers were constantly increasing. Increase of numbers implied increased demand in the way of payment and provisions. Quarrels arose between the new-comers and their British allies. War was determined on. The inlet which divided Thanet from the mainland was passed, and at Aylesford, on the Medway, a battle was fought, which, though it cost Horsa his life, put the conquering Barbarians into possession of much of the east of Kent. The victory was followed by the extermination of the inhabitants; against the clergy especially the anger of the conquerors was directed. The country was thus cleared of the inhabitants, and the new-comers settled down, bringing with them their goods and families and national institutions. This process was repeated at every stage of the conquest of the country, which thus became not only a conquest but a re-settlement. The Jutish conquest of Kent was followed, in 477, by an invasion of the Saxons, who, under Ella, overran the south of Sussex, and captured the fortress of Anderida near Pevensey; and in 495, by a fresh Saxon invasion under Cerdic and Cymric, who passed up the Southampton water and established the kingdom of the West Saxons. A momentary check was given to the advance of the conquerors, in 520, at the battle of Mount Badon. But almost immediately fresh hordes of Angles began conquering and settling the East of England, where they established the East Anglian kingdom, with its two great divisions of Northfolk and Southfolk. Between that time and 577, the date of a victory at Deorham, in Gloucestershire, the West Saxons had overrun what are now Hampshire and Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, and the valley of the Severn, reaching almost as far as Chester; while the Angles, entering the Humber and working up the rivers, established themselves on the Trent, where they were known as Mercians or Border men, and formed two Northern kingdoms, that of Deira in Yorkshire, and that of Bernicia, extending as far as the Forth. The capital of this last-named kingdom was Bamborough, founded by Ida, and called after his wife Bebba, Bebbanburgh, or Bamborough.

The junction of these two kingdoms under Æthelfrith, about 600, established the Kingdom of Northumbria; thus was begun the process of consolidating the several divided English kingdoms. This tendency to consolidation is marked by the title of Bretwalda, which is given to the chief of the nation dominant for the time being. The name had been applied to Ella of Sussex, to Ceawlin[3] of Wessex, and was held at the time of the establishment of the Northumbrian power by Æthelberht of Kent. There were thus two pre-eminent powers among the English—Northumbria, under its king Æthelfrith, claiming supremacy over the middle districts of England, including the Mercians and Middle English; and Kent, under Æthelberht, paramount over Middlesex, Essex, and East Anglia; while a third kingdom, that of Wessex, though large in extent and destined to become the dominant power, was as yet occupied chiefly in improving its position towards the west. Beyond these lay the district still in the possession of the Britons. The possessions of this people were now divided by the conquest of the English into three—West Wales, or Cornwall; North Wales, which we now call Wales; and Strathclyde, a district stretching from the Clyde along the west of the Pennine chain, and separated from Wales by Chester, in the hands of the Mercians, and a piece of Lancashire in the hands of the Northumbrians.

It was while the kingdoms of Northumbria and Kent were thus in the balance that the conversion of the English to the Christian faith began. Æthelberht of Kent had married Bercta, the daughter of the Frankish King of Paris. She was a Christian; and Gregory the Great at that time occupying the Roman See, which was rapidly rising to the position of supremacy in the Christian Church, took advantage of the opening thus afforded, and despatched a band of missionaries under a monk named Augustine to convert the people. In 597 they landed in Thanet. By the influence of the Queen they were well received, and established themselves at Canterbury, which has ever since retained its position as the seat of the Primacy. The Kings of Essex and East Anglia followed the example of their superior Lord, and became Christians. The Northern kingdom was still heathen. But Eadwine, who succeeded Æthelfrith on the Northumbrian throne, surpassed his predecessor in power. On Æthelberht’s death, he received the submission of the East Anglians and men of Essex, and conquered even the West Saxons. Kent alone remained independent, but was compelled to purchase security by a close alliance with Eadwine, who married a Kentish princess. With her went a priest, Paulinus; and priest and Queen together succeeded in converting Eadwine, and bringing the Northern kingdom to Christianity. Heathenism was however not extinct. It found a champion, Penda, King of the Mercians. In alliance with the Welsh king he attacked and defeated Eadwine, in 633, at the battle of Heathfield, and united under his power those[4] who were properly called Mercians and the other English tribes south of the Humber. He also conquered the West Saxon districts along the Severn, and thus established what is generally known as the Kingdom of Mercia. Paulinus had fled from York after the battle of Heathfield. But the contest between heathen and Christian was renewed by Oswald, Eadwine’s successor; for Paulinus’ place was taken by Bishop Aidan, a missionary from Columba’s Irish monastery in Iona, who had established an Episcopal See in the Island of Lindisfarne. From thence missionaries issued, who continued the work of conversion, to which Oswald chiefly devoted his life. Birinus, sent from Rome, with the support of Oswald, succeeded in converting even Wessex, and establishing a Christian church at Dorchester. Penda still continued in the centre of England to uphold the cause of heathendom. At the battle of Maserfield he conquered and slew Oswald, and re-established his religion for a time in Wessex. But at length, in 655, he succumbed to Oswi, Oswald’s successor, and with him fell the power of heathendom. It seemed as though Irish Christianity, and not Roman, would thus be the religion of England. But Rome did not suffer her conquests to slip from her hand. A struggle arose between the adherents of the two Churches. The matter was brought to an issue in 664 at a Council at Whitby. The Roman Church there proved predominant. And this victory was followed by the appointment of Theodore of Tarsus, an Eastern divine, to the See of Canterbury. Under him the English Church was organized. Fresh sees were added to the old ones, which had usually followed the limits of the old English kingdoms. Canterbury was established as the centre of Church authority. Theodore’s ecclesiastical work tended much both to the growth of national unity and to the close connection of Church and State which existed during the Saxon period. The unity of the people was expressed in the single archiepiscopal See of Canterbury and in the Synods; while the arrangement of bishoprics and parishes according to existing territorial divisions connected them closely with the State.

The contest for supremacy between Mercia and Northumbria still continued. After the fall of Penda, the supremacy of the Northern kingdom was for some time unquestioned. But sixty years later, during the reign of three Christian kings, Ethelbald, Offa, and Cenwulf (716-819), Mercia again rose to great power. Offa indeed came nearer to consolidating an empire than any of the preceding kings, although he is not mentioned[5] among the Bretwaldas. It is said that he corresponded on terms of something like equality with Charlemagne; and the great dyke between the Severn and the Wye which bears his name is supposed to mark the limits of his conquests over the Britons.

With these princes the supremacy of Mercia closed, for a great king had in the year 800 ascended the throne of Wessex. Ecgberht had lived as an exile in his youth at the court of Charlemagne, and there probably imbibed imperial notions. During his reign of thirty-six years he gradually brought under his power all the kingdoms of the English, whether Anglian or Saxon. In 823, at the great battle of Ellandune, he defeated the Mercians so completely that their subject kingdoms passed into his power. Four years later Mercia owned his overlordship, and Northumbria immediately after yielded without a struggle. These great kingdoms retained their own line of sovereigns as subordinate kings. Ecgberht continued the hereditary struggle against the British populations, with the West Welsh or Cornish, and the North Welsh or Welsh, and in each instance succeeded in establishing his supremacy over them. North of the Dee, however, his power over the British population did not spread. Thus the kingdom of the West Saxons absorbed all its rivals, and established a permanent superiority in England.

Already, however, a new enemy, before which the rising kingdom was finally to succumb, had made its appearance; a year before his death, Ecgberht was called upon to defend his country from the Danes. This people, issuing from the Scandinavian kingdoms in the North of Europe, had begun to land in England, to harry the country, and to carry off their spoil. At first as robbers, then as settlers, and finally as conquerors, for two centuries they occupy English history. Their first appearance in this reign was at Charmouth in Dorsetshire. Subsequently, in junction with the British, they advanced westward from Cornwall. This led to the great battle of Hengestesdun, or Hengston, where the invaders were defeated (835). It seems not unnatural to trace the appearance of the Northern rovers in England to the state of the Continent. Driven from their own country by want of room, obliged to seek new settlements, they found themselves checked by the organized power of Charlemagne’s empire. They were thus compelled to find their new home in countries they had not yet visited. The reign closed with the capture of Chester, the capital of Gwynedd, the British kingdom of North Wales.