The Three Brains of Taval had spoken! Kenley

must die! The cheerful youth from an earlier

time-strata must enter Death-in-Life. Nothing less

than a cosmic revolt could postpone his decreed fate.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Summer 1940.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The warm, night air whipped Bob Winslow's face as he crossed the open space before Kerla Research, Inc., to the car where Jim Kenley, his roommate and lifelong friend was waiting. A storm was roaring in from the west, revealing the city's skyline at frequent intervals silhouetted against a background of sheet lightning. Bob should have been elated to the point of near explosion, over the news he could give Jim. Bob was to be promoted for his achievements in polarization of the newly discovered Decka light stream, and for his development of the electronoscope that had given astronomy a new universe to explore.

Instead, Bob had a sixth sense of actual fear, as if something invisible—invincible, was trailing him. Recently this feeling had come, sometimes at night, arousing him abruptly, as if actually touched. All today, and now tonight, the feeling grew that a Presence was at hand. Small matter if he was to be director of Kerla Research, Inc., at the age of twenty-six. Bob wondered if his nerves were shot. Maybe, but he felt steady enough.

The car was at the curb and Jim, as far removed from a world of scientific research as one could imagine, swung open the door. "Mean storm coming," he called. "Must be hail in it. Let's scram for home. We can listen in to that night ball game."

Water splashed Bob's face. He was thinking, as he crossed the pavement, that Jim lived as much in the world of sports as he in the field of scientific investigation. Jim Kenley worked hard as an auditor in the daytime. Off duty, it might be football, horse racing, tennis or baseball. He liked all of them, and could hardly wait for the score, or result of a standout event. Perhaps that was why Bob liked Jim so well.

Bob was at the car as the first wave of rain and wind, broken into needle point mist, obscured lights and broke over them. He saw that, and then more. He saw Jim catapulted from the car as if pushed by invisible hands. Then Bob felt himself gripped, and felt, not chill rain, but absolute zero. It surely took no more time than the fraction of a second, before he plunged into a white world—a world without motion, without sound. But in that flicker of time fading so swiftly, Bob saw men in strange raiment, at first opaque, then solidifying. He saw, too, an elongated, golden red craft without wheels; and from it emerged a tall man with a silver skull cap. After that—absolute zero. It couldn't have been a point above. That was Bob's last thought—absolute zero.

A tired sleeper arouses slowly, hovering between consciousness and dreamland because the mind dreads taking over mastership of the body. Such was the way Bob Winslow experienced his awakening. It was so comfortable, to rouse slightly, then plunge back into soft, warm slumber. At last voices disturbed his brain, and light beat against closed lids. With a sigh Bob opened his eyes.

After one startled look Bob closed them briefly. He wasn't in his room. He was in a strange place, a room with tinted, translucent walls and concealed lights. The bed, sheet, everything about it, were odd. Bob started to get up. Sharp pains streaked along arms and legs. They passed and he tried it again. There was so much to take in: the squat chairs of semi-transparent material, the room with a screen at the farther end, flanked with metallic disks. The room itself, while rectangular, had curved corners.

There was a peculiar scent in the room, pungent, yet not unpleasant. It had an exhilarating effect. And Bob thought suddenly of Jim Kenley. He had to laugh then, for Jim bounced up beside him, eyes wide. "Huh," he said. "Tornado hit us? What sort of hospital is this?"

It came back to Bob—his departure from the laboratory building, to the car as the storm bore down. Then the figures—and the machine! That wasn't a dream. For Bob knew he was wide awake now, and this place was real enough. "Maybe," he answered Jim. "I suppose it is a sort of hospital. But where?"

"I'm hungry," Jim announced, yawning. "Ouch! Damned funny. Pains all over. Like I'd been running ten miles. Sa-a-ay! Bob, I got hit out of the car, and somebody piled ice on me. Hey—where the hell's my clothes. Let's get out of this dump. Are there any nurses anywhere."

The disks across the room began to whir, without noise. Before either could speak again, the screen began to send out a soft glow. Then a figure materialized, that of a man, full sized, in a sort of garment fitting like waist jacket and tight trousers, but in a single piece. The man wore a helmet, chromium bright, and looked no more than forty. Bob and Jim waited, the former fully aware that a tremendous change, somehow, had come into their lives. As for Jim Kenley, he merely grunted. "Movies. Gimme Mickey Mouse, or Popeye. T'hell with Flash Gordon."

Then the figure on the screen spoke. His words didn't come from a speaker. As certain as he believed his own eyes and ears, Bob realized the man was actually talking to them, from this screen. "I perceive the actinic frequency treatment has revived you," he said, rather amiably. "Good. Did either of you experience muscular pains yet?"

"Say," Jim Kenley exclaimed, "what t'hell's it all about. Yeah, I got pains. And why? Somebody slugged me, that's why.

"And if we're okay now, how about sending our clothes around, and no bill. I didn't start it. And where are we anyway?"

The man on the screen frowned. "You are not Winslow. No?"

"I'm Jim Kenley. That's Bob. Say—any of you folks phone Bob's outfit he got hurt or something?"

"No." The figure came nearer, growing in perspective. "I believe it is time to inform you it would be somewhat difficult to notify anyone in your period of time what happened. You are now existing in the year 3300."

The pit of Bob's stomach grew chill. Somehow, he had felt from the moment of awakening, that he had left either his space, or his time zone. It fit too well with that presentment, and the brief glimpse of their kidnapers. And as his alert mind began to grasp their situation, Bob went through panic. There were so many things he wanted to complete, to eat, to see. There was a girl, not disturbing him yet, but nevertheless in the background. There was his whole world, the one he knew, and that was the world in which he wanted to live, and die. Bob's curiosity wasn't to explore space. He wanted to better fellow men, and gain information for them. He wondered if Jim could get the staggering impact of this calm announcement of their fate.

Jim's reaction was typical. "Baloney. You gotta damned good act, brother. And I don't know why you're rehearsing on us." Jim sprang out of bed. "Come on, Bob. Let's get out of this booby hatch." In tight fitting pajamas of strange fabric, he started around his bed. He struck an object, bounded back. Whatever it was, Bob couldn't see it. As for Jim, swearing, fists doubled, he charged. This time he went back and struck the floor, turning a complete somersault.

The man on the screen chuckled. "Some take it easy. Some don't. Winslow, I perceive you understand more readily, till you get a more complete explanation. Good. Rest assured you shall get it. Now, if you and your companion walk directly to this screen, I promise you entry to your future quarters. Go there, put on clothing you will find, and wait your summons to food."

Bob nodded. "May I ask a question?"

"Of course."

"Granted this is the year 3300, give me a reason to believe you. A fundamental one. I live in the Twentieth Century, in the year 1940. We recognize the theory that time and space are relative, that the past can still exist. But the future—"

The man's head nodded approvingly. "A sound question, Winslow. For that request, I introduce myself. I am Vasper, assigned to instruct you. Believe me when I say you actually are in the year 3300 and upon the North American continent, in a region once known as Arkansas. So much for that. You grasp the falseness of past time, balanced against space. You understand dimly, I am certain—for it was shortly after 1940 that the Palonian theory of the spiral universe was developed from previous ideas. Well, we know now that the same rule applied to time and space without beginning, has no final boundary. Thus, if there is no beginning, there is no end. If past time and space zones exist, then so must future time and space zones exist. We have proved that very definitely, in your case. I must go now," Vasper added quickly. He smiled, eyes flicking to the dazed Jim Kenley struggling to his feet. "The barrier is gone now. We put it up, for unbelievers. Walk into the screen. I shall visit you there, within the hour."

The disks ceased whirling. The screen faded to flat white, and Jim Kenley leaned against his bed, mumbling. "A nut," he said. "A goof, with the baseball season coming on—and the Belmont Stakes—and—everything. And my job—a bonus if I finished by the first of the month!"

Bob went across to his friend. He felt sick, shaky. The impact of Vasper's revelation was sufficient to daze any man, Bob felt. Now he patted Jim's shoulder. "Then we're two nuts, Jim.

"We're in something, too big to grasp all at once. I'll stick by you, Jim. Come on, let's do what—what Vasper said."

Jim looked long and searchingly at Bob. He gripped his hand. "I'm dumb," he said slowly. "Yeah, I saw men, and a funny looking thing like a gold tank—before they jumped us."

"I saw it, too, Jim."

"Then—then we're really somewhere else." Jim shuddered, then straightened his body. "Okay Bob. I'll try and take it, if I don't go nuts. We walk into the screen, huh? Boy—if that isn't hot. Walking into screens over a thousand years ahead of your time—or is it after."

Still bewildered, the two walked slowly to the screen, kept on as the disks sprang into life again. Bob flinched involuntarily, but he felt no obstacle. They just walked through the screen as if it were a shadow, and they were in a smaller room, with beds similar to the ones they had vacated. There was a screen, much smaller, and chairs of translucent, blue substance. The ceiling was low and glowed faintly, as if reflecting daylight. But there were no windows. Jim walked to a door, and it swung open of itself. "Huh. Kind of an electric eye. Hey, look. Monkey suits."

There was clothing, and the metal helmets like Vasper wore. Bob rubbed his chin. "Well, we might as well try 'em on."

"Yeah," Jim agreed. "But if anybody else I know sees me, I'll be ribbed for life. Say, that's the funniest stuff. Soft as velvet, but thick. Oh well—"

They got into everything but the helmets. "Now what," Jim wondered, handling the headpiece. "Lighter'n aluminum. And it's got earphones, or something. See."

"Put them on," a voice suggested behind them. Turning, they saw Vasper as he stepped casually through the screen. He was a six footer, built like a halfback, with ruddy hair and blue eyes. "We must all wear them in Taval."

"Why?" Jim demanded bluntly.

"Why? For instructions from The Three, of course. They are our leaders and no man may be out of their reach."

At a nod from Bob, Jim slipped on the featherweight headgear. Bob found it didn't interfere with ordinary conversation. Vasper regarded them, smiling. "I know how you feel," he said. "My special task covers your century. That's why I speak your language so well. All Taval speaks English, with variations, for we are descendants of North American peoples. But first, you are to go with me to the Twentieth Century dining-room." He led the way to the screen. By now Bob wasn't surprised at entering a room with a familiar look. It was a restaurant, with a white coated waiter, and the smell of steaming foods. "Boy," Jim cried. "I could eat a four-inch steak smothered with onions. And coffee—smell it Bob. Just smell."

Bob felt like an animal, was conscious of a hunger he had never possessed before. Obviously Jim was in the same mood, for he fairly yanked a bowl of soup from the waiter's grasp. And there was steak, juicy and appetizing. There was bread, coffee, vegetables and even pie. And as they ate, Vasper sat there, smiling as if very much pleased. At last both men knew they were filled. Jim sighed, reached dreamily for a cigarette. "Anyway," he reflected, "it's worth this namby pamby business—a feed like that. Okay, Vasper—let's hear details."

Vasper got up. "I've warned you sufficiently," he said. "I think perhaps I had better take you outside. To see Taval."

"That the name of your city?" Jim inquired, winking at Bob. "How far is it from our home?"

"A few hundred miles," Vasper answered. "And more than a thousand years, this way—"

They walked into the inevitable screen Vasper indicated, and at once found themselves in a green world, almost jungle-like in appearance, with what appeared to be a mist overhead concealing the sun. There were buildings, all domed and apparently resting upon queer looking cushions. There were paths through trees, palms, hardwood, all sorts of flowers and shrubs, but no streets. Through the foliage people were moving leisurely, but not in profusion.

"What's this, a park?" Jim asked.

"Taval," Vasper answered. It was then Bob, drawn by curiosity, began to study the sky. It wasn't blue, but ashy gray. Then he exclaimed, peering more closely. "Why—we're under a great dome—a mile-high one," he cried.

Vasper nodded, smiling. "That's right. Taval—one of the domed cities. There are others—many. All of the Brotherhood."

Jim found a bench nearby, sat down. "One story houses on cushions. With funny round tops. No streets. Everything under glass, or something. My good gosh, and encore. Why did I ever leave home, or did I?"

Bob joined him. He was excited, and yet strongly moved. His keen, scientific mind told him thousands of problems had been solved here in Taval, that Vasper surely was right about the time element. It would take time to grasp all this. And it was too soon to puzzle why he and Jim had been brought here. Now he forced a smile. "Suppose," he said, "you tell us, in a general way, what it's all about."

Vasper sat down between them, while Jim fumbled for another cigarette. "Who'll win the World Series?" he muttered. "The Yanks, of course. But—and there's Placer in the Belmont, smacking 'em over in the Derby the other day. Placer against Agate Second! What a race. And Tennessee and Southern Cal—and Texas A & M. Will they be out in front this fall? Goshamighty. It happened a thousand odd years ago, all this. And I dunno how it came out. I—" Jim's mouth opened. He slapped his knee. "Great day, Bob. Suppose I could check up on all the Derbies, and World Series, and Bowl games for ten years, and got back. Wouldn't I rake in the dough. Say, that's an idea?"

"There is no money in Taval," Vasper said quietly. "You do your task and you are cared for." He turned to Bob. "We are Americans in Taval. At least," he added, "the descendants of your stock. The machine age you created with the United States as the driving force, eventually brought chaos. That and natural disasters. We had few survivors in the world, by comparison. And then there came Taval, for whom this city is named. He discovered the key that divorced time and space—"

"He did," Bob broke in excitedly. "How? We were working on the theory of overtaking time—by spiraling our speed."

Vasper nodded. "Yes, that resulted, of course, in the two adventures to our satellite you called the moon. They were disastrous because you were ignorant of ether frequencies at the upper end of the cosmic ray band. But you cannot overtake space by the spiral theory. Always there would be fractional time, and, therefore, you're always bound by ordinary dimensions."

"One million—two million—ten million, as Amos would say," Jim Kenley put in. "How clear you are, Grandma."

"Shut up," Bob told him. "Then how did Taval work his theory, Vasper? That screen—is it a kind of fourth-dimensional business?"

"It is. But that was worked out later, by a group of his pupils. We use the same base idea of Taval's, as he perfected it back in 2800. Discarding time to overtake, or unwind space as you might define it, he chose to search for a physical way of stopping motion—"

"I've got it," Bob cried, leaping to his feet. "It came to me—the night—the night of the storm—absolute zero! That's it! Absolute zero to stop motion, and therefore, eliminate time and space!"

"Sit down," Jim advised. "I'm Napoleon and you're Little Caesar. Remember? And tomorrow's Mayday.... Absolute zero, huh? Well, I said I felt like I was in a chunk of ice that night."

"But this screen affair," Bob put in. "It—it's different."

"Our method of transportation entirely," Vasper affirmed. "Yes, we need no streets. No walks, save for exercise. Throughout Taval there are outdoor screens, for convenience. Winslow, I said Taval's idea is unchanged. It is, although refined. You were right about your absolute zero. We came to you that way. In the only machine we employ today, save for the manufacture of the skydome, and our laboratory equipment. With absolute zero stopping motion, there is neither time nor space. You know that. Well, the first contact, creating new motion, brings one to the time in which he is revived."

"Freezing like that would kill anybody," Jim protested. "It breaks up tissue."

"You and Winslow suffered all stoppage of motion in approximately one-two millionth of a second, my skeptical friend. We brought you to the portable laboratory, kept you in suspended animation for ten days, then revived you in another fraction as short as the means we took possession of your bodies."

"How long did the process last?" Bob asked.

"It was exactly thirty days since you reached Taval."

Jim whistled. "No wonder I was hungry. Thirty days."

"We injected fluids," Vasper told him. "You see, Kenley, we assimilate food here now chiefly in liquid form. Now the screen—we have reduced a margin of absolute zero between the walls of the screen, to a width that your obsolete measuring system cannot cover. The screen itself is not a physical wall. It is—well, unspatial. That is too advanced for either of you to grasp now. It is sufficient to explain that you touch the absolute zero wall, and are revived, all so instantaneously, that you are not conscious of the change. And in that transition, you reach any destination you head for."

"Simple," Jim groaned. "So very, very simple. Okay, and I thought Aladdin—or whoever he was, just happened to be a myth." Jim studied Vasper thoughtfully. "And now, my good friend, why are we here?"

"You," Vasper announced, "are here because of your friend Winslow. We are few, and we need brains, and fit bodies. Winslow has both. We search the back centuries constantly for men—and women. Men with brains to keep our race, and our world existing. We placed the skydome over all our cities because the sun will cool for a thousand years. We have learned that and must start now, to keep our plant and animal life from perishing, till the cycle ends and the earth grows hot again. You, Jim Kenley, were brought along because you are Winslow's friend, and your company will be of advantage while he adjusts himself to what must be an amazing change in his career."

"A master work of understatement," Bob observed. "Maybe I was serving my time to better purpose. It was all I wanted to do. Do you think I'm ever to be happy here?"

"What sort of ball clubs do you have?" Jim fired at Vasper. "I'll bet there's not even a golf club."

Vasper laughed. "You're due for some surprises, Kenley."

For Bob Winslow, there followed hours that intrigued him. Only here and there did he meet Taval residents. Vasper explained that by going directly from point to point, that there was no traffic, that all duty hours were staggered because Taval at night, was as well illuminated as by day. The chief plants were operated by robot workers, who could reproduce their kind in other factories. "Taval, like our other cities, now needs only brains," Vasper went on. "We maintain sports here to keep our bodies fit." As he spoke, Vasper undid a tiny container hanging to one shoulder, extracted a handful of tiny pellets and swallowed them. At Bob's look of curiosity he smiled. "Energy," he said. "But we use more fluid food than these. Come, while I take you to The Three, your companion is at liberty to go across there to the stadium of sports."

"I'd like to see that too," Bob said. Vasper nodded. He pointed to an outside screen. They entered it and found themselves in a great open air arena. Upon the grass-mantled field a game was in progress, not unlike basketball. Farther away, a group of young women, the first Bob had seen, clad in trunks like any miss of the Twentieth Century, engaged in a game, somewhat like tennis, save that the ball was larger and a dozen took part in each court. Youths were jogging along a circular track, and in the distance was a narrow, but rather long swimming pool. The arena itself, was double the size of any Bob had ever seen before. "I think," Vasper observed, "that should interest Kenley. And now, if you have been listening carefully, there comes an order for us."

Bob heard it now, a voice speaking slowly, some of the words not recognizable. The speaker had no accent. Vasper was watching Bob. "The language has changed," he explained. "That was Fator, the senior of Taval's Three. He must examine you, assign you your future duties."

"Future duties!"

"Of course. Why else did The Three send for you out of time? Your brain is needed, if we prepare to save the world in the centuries to come. There are others we are summoning, if we had more apparatus. Unfortunately, certain elements are scarce, and we have but one—the one in which they brought you here." So speaking, Vasper led the way to another screen.

Somehow, Bob had expected to find an aged, bearded man. Instead, Fator, senior of The Three looked no more than sixty, was clean shaven and his hair was hardly gray. He was at a desk, in a room minus windows, and very similar to the other interiors Bob had already seen here. Fator had his hands upon an inclosed cylinder which gave forth a whirring sound. He wore a look of deep concentration, and Vasper motioned for silence till the cylinder ceased whirring. Then Fator rose, walked across the room and held out a hand.

"I bid you welcome to Taval, Winslow," he spoke slowly, in his stilted manner. "You will find more—more sympathy here, than in your time. More than you had in your own research laboratory."

"Why—you know about that?"

Fator nodded, cold gray eyes flicking over Bob's body. "I notice you are well kept. Splendid. You shall have the same food as you are accustomed to, sir. Your duties are to be with an advanced group—charting our universe—as we reach the Peltior Dark."

Bob stared. "The Peltior Dark," Fator explained, "is as visible now as the so-called—Oh yes, the Milky Way was in your century. We are going to strike it in three hundred and twenty nine years."

"We charted the dark regions with the iconoscope," Bob put in eagerly. "Till then, our astronomers, working with glass scopes, had only a vague idea."

"Still," Fator told him, "our speed toward the first of these abysmal regions accelerated in the last two centuries. Our sun first will expand, then contract. Now you see what we are preparing for."

Bob smiled. "But we'll be gone sir, before this happens."

Fator's smile was enigmatic. "Perhaps—not. For some of us. I trust you are reconciled, Winslow. You cannot go back. Otherwise, you are as free as any resident of Taval. You must remain inside the dome, unless it is directed otherwise. Our sun is two degrees colder today, and ice covers the northern hemisphere outside. You could not escape, but I hardly have to warn you. There are plenty of matters to interest you in our midst. You are that type. As for your companion—"

"Kenley's a sensible chap," Bob cut in. "True, he lives for sports. But he is an excellent auditor—I mean," he floundered, "good at calculation and all that."

"We have machines for that, in our cities," Fator replied. And the way he said it, made Bob feel a tiny cold shudder.

Fator closed the interview with the word that he—Bob Winslow, would be answerable to the Senior of Taval's ruling Three. He further said that Vasper would continue as his instructor for the present. Then, with a nod, he turned back to his cylinder. It was whirring as Bob and Vasper stepped into the screen.

They emerged within the sports arena again, and Bob noted Jim, watching the games. Then he thought of Fator's cylinder. "That?" Vasper replied in answer to a question. "He was dictating. We use a system—phonetic. The fingers of both hands control Taval rays and thereby, the phonetic words. Fator is writing a story of Taval, or rather, bringing the history up to date, with a plan for his successor to carry on. That is," Vasper added, "if he doesn't carry on himself."

"What do you mean?" Bob demanded. "You haven't discovered immortality!"

Vasper shook his head. "Unfortunately, no. But—well, there are whispers. It would be death to mention it openly, what I have heard. Do not ask me. But in time, listen to the whispers."

Jim Kenley trotted across the great field, looking more cheerful. "Say, I told 'em about baseball and they're willing to take a crack at it. And that tennis business the gals have is red hot. Some swell looking kids around here. Hey Vasper—they ever marry in Taval?"

"If The Three decrees, yes. Otherwise, no."

Jim's face dropped. "Heck, just as I had a redhead squinting at me in that way. Oh well, when I wake up she'll be gone, and I'll probably find I'm fired for this spree. Where to now, friend Vasper."

For days they examined Taval, learned that it took in far more territory than they had imagined. They visited the vat farms, where giant plants grew, blossomed and produced heat in the matter of days, fed by chemicals directly to the roots.

They visited factories, where food was prepared as concentrates, where plastics from elements and vegetable tissue were compounded, all by other machines, not at all like Bob's conception of robots. Indeed, a lot of machines were operated by tiny mechanisms, all lens and coils, capable of being carried around by hand. The Taval ray, Bob learned, was a development starting with the so-called electric eye of the Twentieth Century. And it didn't take him long to recognize many fundamentals created by earlier Americans. Then it was he who came to recognize others, brought into Taval as he. Vasper showed him a stout, slow-moving person called Miller, who had ridden on Fulton's Clermont. Miller was a chemist. And there was a slight figure out of the Twenty Second Century, Gregg by name. He was worrying about the First World Confederacy threatened with breakup when he was removed to Taval. Gregg, Vasper explained, had one of the finest of new minds, and was engaged in sinking shafts into the earth's core, to obtain heat for Taval. As for Jim, he had taken up with a group of young fellows, all of athletic build, and all, strangely enough, imported in recent months. Jim mentioned a boxer, who fought in England while Jackson was President; of a runner who broke the mile record in 1995, and of an Olympic star winning his awards at the turn of the Twenty First century. It amused Bob that Jim appeared to fit in so quickly. Already, by one means or other, Jim actually had organized a baseball team, and was considering bowling. "Too bad they ain't got race horses," he complained to his friend. "They tell me there's one section, south of Taval, that's clean given over to cows and hogs and horses. Funny."

"Heard anything about your duties?" Bob inquired.

"Nope. Got hauled up before your friend Fator the other day. He just asked me if I enjoyed my meals, and minded taking part in the sports. Asked if I'd ever been sick, or had any ailments, and they typed my blood, and a lot of other things."

At Bob's look, Jim laughed, shrugged his shoulders. "Oh, they're doing the same thing to the other fellows. And say, Bob. Soon as I get acclimated, Vasper says, they want me to live at the stadium, with the other beef eaters."

Bob didn't know why, but he had a premonition then, of some menace directed at Jim and his friends. But he was about to be taken to his group, and Bob felt a growing excitement at the prospect. He couldn't help that, for Taval, scientifically speaking, was a treasure house for any man of Bob's type. Vasper told him he should feel proud, in that he was the only newcomer, other than an actual native of Taval, to join this advanced group.

The day Bob heard Fator's voice over the headphones, summoning him to face the screen, Bob's pulse was racing. Fator did him the honor of standing before his desk as he spoke. "I am addressing the other members of the advanced group," he said. "Winslow is to join you now. Instruct him faithfully, and remember he has so much to study, before he can be of value to you, and Taval. Come forward, Winslow, and join your group."

As Fator vanished, Bob turned, gripped Vasper's hand. The latter looked sad. "Now I must go back—for another," he whispered. "Good luck—Bob."

He was due for a surprise, to find the advanced group atop the great dome, living in translucent quarters, a mile above Taval. There he met Kalen and Forg, the two scientists in charge. He was shown the rayscopes, that literally crawled along light waves, to annihilate time and bring before the human eye universes a billion light years away. There too, he studied the black wastes of Peltior Dark, and saw the spectograms that revealed the choking gas areas through which they must pass.

There was so much to learn, so much already learned, that Bob Winslow forgot ordinary hours. The phonetic language wasn't difficult. He spent his allotted hours in the library, and both Forg and Kalen, men high in years, yet with agile minds were patient in revealing discoveries some of them already centuries old. They told him that the entire universe would suffer, and they were gambling upon a chance to survive such intense cold passing through Peltior Dark, that the atmosphere would thaw inside five centuries. After that, they had concluded, provided there were no changes in the solar system, the sun would resume its natural sphere.

"Is there a way of traveling ahead as I have come," Bob asked. "So that we might learn our fate?"

Forg looked at Bob thoughtfully. "We have been afraid—of utter destruction," he said finally. "In that case, we could not return. But if someone bold enough to make the venture tried it—" He broke off. Bob knew Forg was thinking of him. All right, he concluded. And even then, the germ of an idea was born in his mind.

At the end of the first month, Fator summoned him again. He was pleased with Bob's progress. It was even more than they had expected. He asked about Bob's health, then smiled. "I believe a rest period would benefit you," he said. "You may find your friend Kenley and spend five days—as you wish."

"Could Vasper share the rest period with me?" Bob inquired.

"Yes. I shall advise him. He has been back to your century. He delayed, for your benefit. You shall learn, upon seeing him."

Vasper had brought back two more young men. Likewise, he had some magazines and newspapers. He delivered these in Jim's presence and the latter grabbed for the sports pages. Bob picked up his choice paper. There was a headline, and pictures.

THREE DEAD, 47 HURT IN TORNADO

Bob saw pictures of twisted buildings, wreckage, littering streets. The entire downtown section of his home city had suffered. Kerla Research structures had been particularly hard hit. And there, at the bottom of the page, was his own photograph.

YOUNG DIRECTOR OF KERLA RESEARCH LOST, read the caption.

Many bodies were still buried in debris, Bob read, and it was assumed Bob had met such a fate. Jim interrupted. "Sa-a-ay. The Cincy Reds are coming right back. Can you tie that? And the Cards—sa-a-ay. The Nationals will be all tied up again this year. And—" Jim crushed the paper, tossed it away. He got up, face pale.

Bob laid his paper aside, walked over and patted Jim's shoulder. "They said it was a tornado, just as we got kidnaped, Jim. I'm supposed to be killed. And maybe you. We'll have to forget it, Jim."

"I wish to hell Vasper hadn't stopped on his way back. Or—that's the particular hell of it. Vasper going back. And coming just like coming home on the bus. And look at us. Look at us. Now I want to get back. Back home. To hell with this—all of it."

"Hush Jim. Shut up." Vasper looked sorry. He shook his head. "I thought I was doing you a favor," he apologized. "To tell the truth, I had never seen such a storm, and I wanted to know how—how intense it was myself. We—we almost gave up taking you back because of the disturbance."

"I wish it had blown you to the year 50,000," Jim said bitterly. "Now I'm thinking of Yanks and Reds and Cubs, and football and racing, and—of everything."

Vasper removed his headgear as Jim sauntered into another room. He motioned for Bob to do the same thing. In wonder, Bob obeyed. Watching the screen constantly, Vasper drew nearer. "Did you hear—whispers?" he asked anxiously. Bob shook his head.

Vasper hesitated. Then, "I like your friend Jim. Many young men do. But he is doomed."

"What!"

"Not so loud," Vasper said in lower tones. "Jim Kenley is doomed, unless some way is found. The young men are afraid, as more like Jim—with strong bodies and no great brains, are being brought here."

"Go on," Bob answered. "I betray no secrets. What do you mean?"

"Bodies are plentiful, but brains are not. Bodies can die, but brains must survive. The Three have decided that."

Ice raked across Bob's heart. "So what?"

"At last they know—how to transfer the mind from body to body. Now, do you understand?" Quickly Vasper slipped on his headgear. Bob imitated his action mechanically. They were not a moment too soon, for a figure passed across the screen, bearing an apparatus resembling a miniature camera. It vanished. Vasper nodded. "Room inspector. He records everything as he goes across the screen." And now Jim returned. Vasper suggested going outside. Bob remained in the room. He wanted to think.

Vasper had taken a real chance to get this information to him. Now he understood why Jim was removed to the stadium barracks. Taval's rulers had stumbled upon something, more important probably than all other findings. Brain transference! Old men gaining immortality! Young men doomed, to premature senility, then death! And Jim among them. Bob felt sick now.

There must be a way out. Bob felt his debt to Vasper, for undoubtedly the latter knew more than he had revealed. Now a chance remark of Forg's made recently bobbed up in Bob Winslow's mind. "We won't have to worry about leaving our work undone." That was what Forg had said. It tied in with another comment by one of the advance group, who vouchsafed the information to Bob that there would be few additions to their division.

Jim returned at that moment. He started talking about organizing two baseball nines. "Calling 'em the Yanks and Cubs," he laughed. "Say Vasper—where you going?"

Vasper had been listening intently, obviously to a message over his headphone. He whirled, raced toward the screen and vanished. "Can you tie that," Jim exclaimed. "He's a funny duck. But a good scout, Bob. I mean, like us. He—"

Two men materialized on the screen. They stepped into the room. Addressing Jim, one, a swarthy, wide-shouldered man spoke. "You are to come with us."

"Me? I'm suppose to be on leave."

"I had permission for him to join me," Bob put in.

The swarthy one looked at Bob. "I have orders," he said slowly.

Jim swore, looked thoughtful, then shrugged his shoulders. "In this place, they don't fool with you," he mused. "Okay. See you later, Bob."

Panic gripped Bob. Vasper hadn't skipped out because of his own orders. Somebody had tipped him off. "Wait a minute," he addressed the men. "Maybe I can straighten this out. Fator—"

"We are under Fator's orders."

Jim looked pale. "Keep a stiff upper lip, Bob. I know more than you thought. See you later—if you won't recognize me—"

For quite a while Bob Winslow paced the room like a caged animal. Jim did know something. Maybe Vasper had told him, too. Maybe a lot of young men in Taval were whispering the dread news around, helpless yet, hoping for some sort of break to check this menace. It was some time later when Vasper entered the room, caught Bob's eyes with a motion for silence, beckoning him at the same time. Curious, Bob came to him. Vasper held out his hand, pointing to the screen.

They entered a small room, not well lighted. It had no occupants. That is, not till Vasper removed his headgear, as did Bob. The room had a false front, painted to resemble walls and furnishings. Two young men were in the semi darkness behind the false wall.

"Godi and Lelan," Vasper whispered. "They have arranged this room, once a guard room and forgotten. They have knowledge."

"About what? Why they came for Jim?"

"Yes," said the one known as Godi. "Lelan and I are sons of men near The Three. We know Fator has learned brain transference and plans to experiment, first with Forg, of your own group."

"When?"

"Within the hour. That is why he sent for Jim Kenley."

Bob looked at the three, all sober faced, rebellious. "You like Jim," he suggested.

"He is—swell," Godi put in. "That is his word for things he likes. Fator has no right to take any of our bodies, for housing brains of old men."

"But we are helpless," Lelan sighed. "Godi and I, like others born of Taval families, are safe. But the Jim Kenleys brought out of time—they must suffer. It is not right. When I am old I am ready to die."

Vasper nodded. "I do not want to go back, and take men of my age, for such purposes. It's murder, no less. We do not believe in murder, here in Taval."

Fator! He had appeared so benevolent. He was a brilliant man. Bob could understand in a way. Fator was ambitious for his period of stewardship, to reach all the goals he had set. And he could live himself, through his brain, till he had gained those objectives. And Forg! Jim's body and Forg's brain, toiling at his own side in the years to come. Bob shuddered. But what to do? If the experiment was so nearly at hand—

Yes, there was a chance. It came to Bob in a wave of inspiration. It was a chance that had about as long odds as his own at returning to 1940. The single, time-space transfer machine! If it could be called a machine. Vasper should know of it. He had made so many trips. Now he met his Taval friend's troubled eyes. "The machine," he whispered.

Vasper looked scared. "No. One dies attempting to even touch it, except at Fator's orders. It is a sacred trust of a hundred men. To try and reach it means you would be exploded, into sheer gas."

"But if Fator gave an order," Bob went on, "what then?"

Vasper shrugged his shoulders. "Obedience, of course. But Fator will not give such an order."

Godi plucked Bob's arm. "I think I understand," he spoke quietly. "If such an order was given. In Fator's place, I mean. Then one would die, but perhaps you could gain the machine."

"True, Godi. But the only little item lacking, is how to give that order, and then keep Fator from canceling it."

"I think I could attend to that," Lelan put in. "My duties are in the rooms of The Three. I know that the other two are sick old men, and Fator alone directs us. I know his directing room, from where all his orders originate. In fact, I go in and out at will, because I am responsible for all equipment."

Bob looked at Vasper. "Where would this experiment be held—Forg's, and Jim—"

"I do not know, unless it be in Fator's rooms. Again, it might be somewhere else. Fator has a secret workroom."

Bob sank to a stool, mind going over the picture. Presently he looked up at Lelan. "If we left here at precisely the same moment, you to the directing room, Vasper and I to where I could be near the time-space transfer machine, I'm willing to, well, make a try and get in the machine. But Vasper, or someone must tell me what to do."

"That is impossible," Vasper told him. "However I can operate everything. Winslow, I wish to go with you and Jim. Back to your 1940."

"But they'd come and get us—I mean you in particular."

Vasper smiled. "There is one way, my friend, they cannot reach us. We keep the machine. But before that, we take Fator along, to drop into another time. Then there will be no brains transferred, and there will be no new machine, for many, many years. I know. This one took fifty years of construction."

"We might fail," Bob muttered. He looked at Godi and Lelan. Godi spoke up. "I have heard whispers of Fator's secret workroom. Maybe I can find it, if you fail otherwise. I leave now." He turned, pressed Lelan's hand. "We do this for Jim Kenley, one—one swell sportsman," he said, then hurried around the false wall.

They stood there for minutes, the remaining three, whispering final details, Bob felt alternate hot and cold chills now, as he realized his own end, should they fail. Or Lelan fail. Lelan assured them he would not fail. "You shall have the orders before the count of ten," he swore. "The guard will fall back and admit you."

They walked around the false wall, toward the screen. Then the trio stiffened. A room inspector, his tiny apparatus turned their way, was visible. Now he entered boldly. "What's this," he demanded. "This place—you three—unauthorized here!" He pressed the side of his apparatus and a pale light flickered. Vasper and Lelan leaped together, struck the room inspector, all three crashing to the floor. Vasper got up first. He snatched a plastic chair, brought it down on the man's head. Lelan was jumping up and down. "The alarm's given. We've got seconds, at the most. Now—now—we've got a chance—"

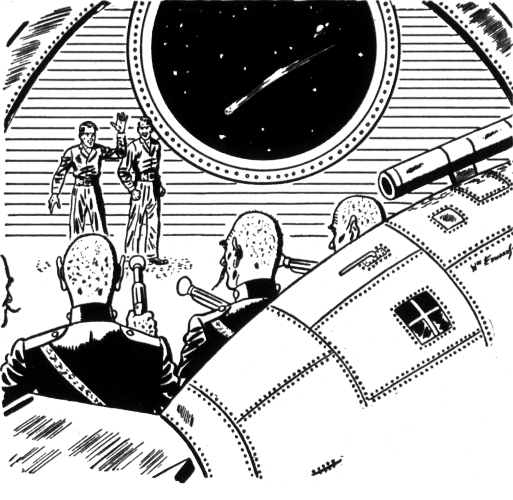

Lelan went through the screen first. Then Vasper grasped Bob's hand. "Just go with me," he cried. "Don't think where you're headed." They came into a large, domed structure, and Bob saw it—the golden hued, snubnosed machine, looking more like a submarine than anything else. Guards were tumbling out of screens. They bore slender, black wands. But already Bob knew those wands could blast any known substance, at almost any distance. The men formed a circle about the machine, and wands were leveled at the pair. "If Lelan fails—we're gone," Vasper cried. "They have orders to kill—anyone. Unless the word comes."

They were a hundred feet from the machine, before the largest screen. It was hopeless to rush the men. For even if Vasper could get inside the machine, they would be gas instead of humans before sprinting twenty feet. It was tempting to wheel and dash back through the screen. And yet the alarm surely was out now, and it wouldn't take long to identify the guilty. Then it was that Vasper cried out. "Look. They've made no move. They have the order from Lelan."

Not a guard moved, true, but the wands were still leveled. And now Vasper strode forward. Bob's knees felt weak, but he followed. Panic was upon him, so much that he felt an almost overwhelming urge to dash for the machine. As for Vasper, he spoke no word. It was evident the guards were dumbfounded, still suspicious, but powerless for the moment to halt them. And Vasper reached up, moved a hand and a door slid open. The pair entered.

Already the men outside were in motion. As one a half hundred rushed toward the door. But Vasper had it closed. "Lelan's in trouble," he called, running forward to a turret. "Hang on. We're going to Fator's quarters—to his entrance hall."

The domed ceiling melted. In one continuous motion they seemed to blend into another building, beneath another dome, more brightly lighted. There were men, guards, but Vasper groaned. "Fator is not here," he shouted.

Bob was conscious of a voice sounding in his earphone. It was high pitched, insistent. "Tell Vasper—my legs are gone. Fator—Stadium—underneath—" Lelan's voice died in a great sigh. Bob pictured the onrush of guards, blasting their friend's body bit by bit into gas. Bob shouted the words to Vasper, who nodded. They made the arena field first, and there was Godi, racing toward them and pointing toward the tower overlooking the stadium entrance. Then Godi reached the tower, pointed downward.

Even as Godi pointed vigorously into the earth, he seemed to swell, to grow abruptly, into a white cloud that became mist. Guards were coming across the field. Vasper circled the machine above the dissolving mist. Then, with an air of decision, he pointed the machine earthward.

This was no sudden transition by means of fourth-dimensional powers. The machine struck, and they became the center of an exploding mass of soil and masonry. And as quickly, they dived into a great, underground chamber.

There, visible to the invaders, was Fator. There were two beds, side by side. One held Jim Kenley, bared to the waist. Forg was stretched upon the other. Fator had his hands upraised, and Vasper got down, ran to the exit and waved his hand. "You take Fator. I'll take care of Jim," he called. Bob was outside as quickly. He realized the chance they must take now. Let the screens pour in a horde of guards and the machine's security for them would vanish. Fator was fumbling for a wand. It had fallen to the floor. Now Fator was bent over, hand outstretched. Bob made a dive. He struck the director of Taval, sent him beyond reach.

Vasper was racing toward the machine with Jim's body. Forg made feeble efforts to raise as Bob, the death wand in his possession, grabbed Fator's arm. "Get up," he snarled. "You kill no buddy of mine, for his body. Get up, or I'll blow you out of Taval."

Fator wasn't calm now. He looked wolfish, screaming curses, clawing for the wand. He resisted, and Bob started dragging him. And now men did pour forth from screens, wands before them. "Blast him," Fator shouted. "Quick—"

Bob yanked Fator around, holding him as a screen. He held the wand before him. "Okay," he said. "Let's start."

It was a bluff. Vasper shouted encouragement. But Fator fought, and almost pulled away, while guards circled at a safe distance, hesitating to attack. They followed, till Bob was below the machine entrance. It was a three-foot climb, and Fator himself laughed. "When he turns to push me in, use the ray," he ordered.

Bob stood there. He was stymied. He heard Vasper talking. He must be talking to Jim. Then Bob felt a hand. "Jim's coming around," he said. "Hold tight when we pull." Hands slid under both shoulders. Fator let out a scream of sheer terror now, and both Jim and Vasper tugged. Guards ran toward them. Vasper calmly snatched Bob's wand. He made a quick flip and the room became a cloud of white mist. Then, as he and Jim pulled Bob and Fator inside, Vasper closed the door and jumped for the control turret. Fator was still struggling, but Bob and Jim held to him, as Vasper directed. Up through the earth they roared and the stadium field was in bold relief, for one brief moment. It was Bob's last glimpse of Taval. For the roaring increased, and the ports admitted a nightmare of flashing, ever-changing lights, coupled with deepest darkness. Then the roaring stopped. The lights slowed. Motion ceased; Vasper climbed down, stared at Fator thoughtfully. "Your brain can hunt a body—in the Sixth Century," he said.

Bob saw green fields, the ocean in the distance, blue and dotted with sails. They were atop a hill, and vineyards stretched downward, to a city at the water's edge. Fator stared, then nodded. "I was too ambitious," he sighed. "Too ambitious." He stepped down, without a backward look. Vasper closed the door, and when he reached the controls, the roaring, and the succession of shifting colored lights, like tinted lightning, recommenced. Bob had no idea how long it took them. Jim, looking pale, suddenly woke up fully. "Gosh," he shouted. "I wish we could go back, for a while," he called.

"Why?" Bob wanted to know.

"Why—right away my Yanks and Cubs were to tangle for a five-game series, and Lelan's to pitch for the Cubs."

Bob looked at Vasper, who smiled sadly, shook his head. Bob didn't explain what had happened to Lelan, who had given his life for this friend from the Twentieth Century. Then the machine jolted to earth. It was night outside. Vasper opened the door, extended his hand. "That glow is your home city," he said. "You have been away exactly sixty-one days, my friends. Perhaps you can explain that both were taken to hospitals out of the city during the excitement, after the great storm, and your identities were lost, due to great stress."

Bob nodded. "Yes, that can be explained. We'll arrange that, Vasper. But now, the problem is—well, you. Come and live with us. We'll make it up, for all this."

But Vasper shook his head. "No. I would be difficult to explain, perhaps. Or at least, my conveyance, eh?" He smiled.

"But you can't go back to Taval," Jim protested. "You've broken a half dozen laws, and swiped their precious machine."

"True. I doubt I could ever return," Vasper affirmed. He sighed. "I've been something I regret now. Very much. But life has its compensations, Bob and Jim. Perhaps I would have kept right on, kidnaping, as you say, to bolster up our civilization. But Fator's discovery—that made the difference. It is possible there might be a revolt in Taval. I can discover that, by visiting a later time than the year 3300. Meanwhile," he added, "there are some many periods of our history I want to investigate. From the beginning. Think of that. The stone age. The ice ages. When the world was young. I can go when and where I please, right on down the ages. What a story I could dictate, when I grow old."

"You make me want to join you," Bob muttered. But he already felt a curiosity about Kerla Research, and the rebuilding. He could think of a particular restaurant, and of shows, and people he wanted to talk with again. Jim put it into words. "Boy-oh-boy. Shows. Who won the Belmont. And they're thinking of the Series—and football. And all the gang—they'll want to know where I recovered, huh. And my folks—" Jim's voice broke. As for Vasper, he put an arm about Jim's shoulder. Then he came over, pressed Bob's hand. "Maybe," he smiled, "I might visit you, some time, and take you for—well a sort of leave. If you care."

"Care! I'll make it my vacation this same time next year. For a month. We'll go back—and forward too. And Jim—"

"You're wrong there," Jim said flatly. "I'll entertain Vasper here, in good old 1940, or 45. But I'm not leaving this place, unless," he added, "I can run up ahead six months some time, and get the series and Bowl game results. You know, just for luck."

And that was that. Vasper reentered the golden tinted machine. They could see him, silver headgear gleaming, through the turret plastic hood. He waved a hand. Then a roar, and the machine was gone.

Below, lights of a row of cars marked a highway. Bob and Jim, both silent, trudged down the hill, toward the highway. Once more they must live where time and space counted very much indeed.