The Project Gutenberg EBook of Cave-Dwellers of Saturn, by John Wiggin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Cave-Dwellers of Saturn Author: John Wiggin Release Date: April 5, 2020 [EBook #61759] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CAVE-DWELLERS OF SATURN *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Across Earth's radiant civilization lay the

death-shot shadows of the hideous globe-headed

dwarfs from Mars. One lone Earth-ship dared

the treachery blockade, risking the planetoid

peril to find Earth's life element on

mysterious Saturn of the ten terrible rings.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1939.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It was a crisp, clear morning in the city of Copia. A cold winter's sun glinted on the myriad roof tops of the vast spreading metropolis. To the north, snow-covered hills gleamed whitely, but the streets of Copia were dry and clean. There were not many people stirring at such an early hour. The dozen broad avenues which converged like the spokes of a great wheel on Government City in the center of Copia were quite deserted. There was little apparent activity around and about the majestic Government buildings, but the four mammoth gates were open, indicating that Government City was open for business.

At the north gate the sentry, sitting behind his black panel with its clusters of little lights, switches, and push-buttons, glanced upward. There was a faint humming and a man was circling downward about a hundred feet above him. The rays of the early sun flashed off a helmet and the sentry knew that this man was a soldier. The newcomer dropped rapidly, the stubbed wings on his back a gray blur. Then the humming ceased as the soldier switched off his oscillator and landed lightly on the ground before the sentry.

The sentry's swift glance took in the immensely tall, broad-shouldered figure, covered to the ankles in the green cloak. He took in also the pink, smiling face and merry blue eyes, and the lock of bright red hair which showed as the soldier pushed his helmet backward off his forehead.

"Your business?" asked the sentry.

"I have orders to report to the Commander-in-Chief," said the soldier, with a pleasant smile.

"Let's see," said the sentry, glancing at the insignia on the helmet, "you're a decurion of the Eightieth Division. And the name?"

"Dynamon," said the soldier.

"Oh, yes," said the sentry, with a recollective smile, "I remember you as an athlete. Didn't I see you in the Regional Games two years ago?"

"Yes," said the soldier, with pleased surprise. "I was on the team from North Central 4B."

"I thought so," the sentry chuckled. "As I remember you walked away with practically everything but the stadium. Hold on a minute now and I'll clear the channels for you."

The sentry bent over the panels, punched some buttons, threw a switch, and recited a few words in a monotone. He listened for a moment, then threw the switch back and looked up.

"It seems you're expected," he said, "third building to the right and they'll take care of you there."

Ten minutes later Dynamon stood in the doorway of a large, beautiful room and saluted. The salute was answered by a grizzled, dark-skinned man sitting behind an enormous desk. This man was Argallum, Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the World. He rose and beckoned to the young soldier.

"This way, Dynamon," said he, opening a small door. "What we have to talk about requires platinum walls."

Dynamon's face was a mask as he followed the Commander-in-Chief into the little room, but his heart was pounding and his mind working fast. The platinum room! That meant that he was about to learn a secret of the most vital importance to the world. He remembered now, that there was a delegation of Martians in Copia. They had arrived about a week before, ostensibly to carry on negotiations in an effort to avert the ugly crisis that was developing between Earth and Mars. But the conviction was growing among the citizens of Copia that the chief object of the Martian delegation was to spy. It was a well-known fact that the grotesque little men from the red planet had a superhuman sense of hearing that seemed to enable them to tune in on spoken conversations miles away, much as human beings tuned radio sets. They could hear through walls of brick, stone or steel; the one substance they could not hear through was platinum. Hence the little room off the Commander-in-Chief's office which was entirely sheathed in this precious metal.

Argallum sat down heavily behind a little desk and gestured Dynamon to be seated opposite him.

"On the basis of your fine record," said Argallum, "I have selected you, Dynamon, to lead a dangerous expedition. You may refuse the assignment after you hear about it, and no blame will attach to you if you do. It is dangerous, and your chances of returning from it are unknown. But here it is, anyway.

"The situation with Mars is growing worse each month. They are making demands on us which, if we accepted them, would destroy the sovereign independence of the World-State. We would become a mere political satellite of Mars. But if we don't accept their demands, we are liable to a sudden attack from them which we could not withstand. They have got us in a military way and they know it. We might be able to stand them off for a while with our fine air force, but if they ever got a foothold with their land forces, then it's good-bye. They have a new weapon called the Photo-Atomic Ray against which we have absolutely no defense. It's a secret lethal ray which far outranges our voltage-bombs and which penetrates any armor or insulation we've got."

"Now, of course, our Council of Scientists has been working on the problem of a defense against the Ray. But the only thing they've come up with is a vague idea. They believe that there is a substance which they call 'tridium,' which would absorb or neutralize the Photo-Atomic Ray. They don't know what tridium looks like, but by spectro-analysis they know that it exists on the planet Saturn. So I am sending you with an expedition to Saturn to find, if you can, the substance known as 'tridium,' and bring some of it back if possible."

"Saturn!" gasped the decurion.

"I said it would be dangerous," Argallum said, bleakly. "No human being has ever set foot on the planet, and very little is known about it. But that's where you'll find tridium, if we're to believe Saturn's spectrum. You will have the latest, fastest Cosmos Carrier. You will have a completely equipped expedition. You will have for assistants the best young men we can find. As head of the expedition, you will be promoted to the rank of centurion. Do you accept the assignment?"

"Yes, sir," said Dynamon, unhesitatingly, "I accept the assignment."

Dynamon walked thoughtfully out of Government city by the North Gate. The sentry noticed that his helmet was now adorned with the badge of centurion, and came to a smart salute. Dynamon went past him without seeing him, and the sentry glared after the new centurion disapprovingly. Lost in thought, Dynamon kept on walking until he came to with a start, and found himself in the middle of the shopping district.

The sun was getting uncomfortably warm and Dynamon switched off the electric current that heated his long cloak and looked around him. A sign in a shop window said, "Only fourteen more shopping days before the Twenty-fifth of December." Dynamon sighed. He wouldn't be around on this Twenty-fifth and it was going to be a very gay one. It was to be the nine hundredth anniversary of the Great Armistice—from which had come the unification of all the peoples of the Earth. Dynamon sighed again.

The long peace was threatened.

The Earth, in this year of grace 3057, was a wonderful place to live in, and Copia was the political and cultural center of the Earth. For nine hundred years now, the peoples of the Earth had lived at peace with one another as members of a single integrated community. The World-State had grown into something which that war-torn handful of people back in 1957 could scarcely have imagined. No longer did region war against region, or group against group, or class against class. Humanity had finally united to fight the common enemies—death, disease, old age, starvation.

And on this nine hundredth anniversary of the Great Armistice, the people of the World would have a great deal to celebrate. Disease was now unknown, as was starvation. Arduous physical labor was abolished, for now, the heaviest and the slightest tasks were performed by machines. Pain had been reduced, both physical and mental. Helpless senility was a thing of the past. Death alone remained. But even death had been postponed. Human beings now lived to be almost three hundred years old.

All in all, Dynamon mused, as he strolled along the broad avenue, the human race had evolved a pretty satisfactory civilization. More was the pity, then, that human restlessness and vaulting ambition should have led to the construction of the great Cosmos Carriers. If Man had been content to stay on his own little planet, then communication would never have been established with the jealous little men of Mars, and this beautiful civilization would not now be threatened by a visitation of the terrible Martians and their frightful Photo-Atomic Ray. Dynamon's deep chest swelled a little with pride at the thought that he had been selected by the Commander-in-Chief to take an important part in the coming conflict.

He turned the corner and found himself standing before an imposing building. Across the top of the facade in block letters was the legend, "State Theater of Comedy." A few minutes later he stood in front of a doorway at the side of the great theater building. The door opened and a tall, lovely girl appeared.

"Dynamon!" she exclaimed, "I didn't expect to see you for another ten days." She stepped out of the doorway, and reached her arms up impulsively, kissing Dynamon.

The tall young soldier gripped her shoulders hard for a minute, and then stepped back and looked down into her soft brown eyes.

"Yes, I know, Keltry," he said soberly. "I had to report on short notice."

"Oh!" said the girl called Keltry, "are you here on duty?"

"Very secret duty," said Dynamon with a meaning look. He twiddled an imaginary radio-dial in his ear and looked around mysteriously.

The smile died on Keltry's smooth brown face, to be replaced by an expression of concern.

"You mean—them?" she whispered.

Dynamon nodded. "Yes, I am being transferred to a new post," he said slowly, "and I thought, if you had no objections, I would ask to have you transferred along with me."

"Do you need to ask a question like that?" said Keltry. "You know perfectly well I'd have a lot of objections if you didn't ask for my transfer."

"There may be some danger," he said, giving her an eloquent look.

"All the more reason why I should be with you," Keltry said quietly.

Four days later, a conference was breaking up in the platinum room behind the Commander-in-Chief's office. Argallum stood up behind his desk and carefully folded a number of big charts. He laid one on top of another, making a neat stack on the desk, then he looked keenly at the four young men standing before him.

"Once more, gentlemen," Argallum said, "for the sake of emphasis, I repeat—Dynamon has complete authority over the expedition. You, Mortoch"—looking at a lean, hawk-nosed man in a soldier's helmet—"are in command of the soldiers. And you, Thamon"—turning to a studious, stoop-shouldered man—"are in charge of civilian activities. And Borion"—glancing at a stocky, broad-shouldered figure—"you are responsible for the Carrier. But in the last analysis, you are all under Dynamon's orders. This is a desperate venture you're going on and there can be no division of authority."

There was a moment of silence. Argallum seemed satisfied with the set, determined expressions on the four men in the room with him. "Are there any further questions?" he said.

Dynamon shifted his feet uneasily. "Is the decision—on Keltry, final?" he said huskily.

"I'm afraid it is, Dynamon," said Argallum, gently. "I had the director of the theater over here for half an hour trying to talk him around, but it was no good. He said he would under no circumstances spare Keltry. He said she was the most promising young actress in Copia, and that he would forbid her to go on any dangerous trip. Inasmuch as Keltry is still an apprentice, the Director has full authority over her. I can do nothing."

Dynamon drew himself up to his full height and squared his shoulders. "Yes, sir," he said briefly.

"Very well then," said Argallum, "I won't see you again. You will take off from Vanadium Field promptly at four o'clock tomorrow morning. Every one of the one hundred and twenty-nine people on the expedition has his secret orders to be there at three. Dynamon, you have a hand-picked personnel and every possible resource that our scientists could think of to help you. May you succeed in your mission."

"Thank you, sir," they chorused.

Argallum shook hands separately with each of the four men, after which they filed out of the platinum room.

Outside the War Building, Mortoch, the decurion, and Borion, the Navigator, took their leave of Dynamon and strolled away toward the West Gate. But Thamon, the scientist, fell in stride with Dynamon.

"For your sake, I'm sorry," said the stoop-shouldered scientist shyly, "I mean—about Keltry."

"Thanks, Thamon," said the centurion. "It was a nasty blow. I don't know how I'm going to get along without her. I guess I'll just have to."

"Well—I just wanted you to know," said Thamon, "that I sympathized."

In the middle of Vanadium Field a great gray shape, like a vast slumbering whale, could be indistinctly seen in the soft half-light of the false dawn. No lights showed on the field and no sound was heard. But scores of people clustered around the sides of the Cosmos Carrier, dwarfed to ant-like proportions by its great size. Inside the Carrier, standing near the thick double doors in the Carrier's belly, was Dynamon, near him his three chief lieutenants, Mortoch, Thamon, and Borion. The members of the little expeditionary force filed past the youthful Commander, each one halting before him for a brief inspection. One hundred brawny soldiers, divided into squads of ten, stepped through the double doors, each squad led by its decurion. Dynamon ran a practiced eye over the equipment of each man and then for good measure turned him over to the scrutiny of the Chief Decurion, Mortoch. Then came twenty-five civilians, including ten engineers, four dieticians, five administrators, and six scientists. But for a cruel prank of fate, Dynamon reflected, his own dear Keltry would be a member of the expedition.

But there was no time for regretting that which could not be. Dynamon turned and walked toward Borion.

"Are you satisfied?" he asked the navigator. Borion nodded, and Mortoch and Thamon likewise nodded in answer to Dynamon's unspoken question.

"All right," said the young centurion. "Stations!"

A moment later the great outer door of the Cosmos Carrier swung silently shut, after which the thick inner door was secured and the great ship hermetically sealed. Dynamon followed the navigator into the control room.

"This is a gorgeous ship!" said Borion. "It's absolutely the last word. There's a cluster of magnets underneath our feet that are brutes and yet they can be so finely controlled, I'll guarantee you won't feel a bump at any time. Dynamon, these magnets are so strong that this ship will go at least ten times faster than anything that has yet been built. Once we get up out of the stratosphere, beyond the danger of friction, we can go almost twenty miles a second. You ready for the take-off? If you want to use the loud speaker system just throw that switch."

Dynamon nodded; a moment later his voice was heard in every compartment of the Cosmos Carrier.

"Men, we are taking off. Hold your stations for five minutes, after which you may take your ease until further commands."

"Come and watch the altimeter," Borion said after Dynamon closed the loud speaker switch. "You won't believe we're off the ground, these controls are so smooth." The centurion watched the needle creep gently upward a few feet at a time. But he could feel no trace of motion.

"I'm going to take her up vertically to two thousand feet," said Borion. "Then we'll be clear of all obstacles and can pick up our course horizontally—"

"Yes, good," Dynamon broke in quickly, "but don't tell me your course until we are out of the stratosphere."

"Aye, aye, sir," said Borion with a wink, "little pitchers have big ears, don't they?"

"How soon will we get out of the stratosphere?" Dynamon asked.

"Well, I'm lifting her very slowly," answered the navigator, "I don't want to take any chances on friction. I would say in about three hours from now we will be ready to go."

"I will be with you then," said Dynamon, and walked out the door.

The young centurion had in mind to make a thorough inspection of the entire ship, but he had scarcely been ten minutes away from the control room when the loud-speaker system boomed forth.

"Centurion Dynamon is requested to come to the control room." Dynamon hurried up a metal staircase and then through a companionway. As he threw open the door to the control room, Borion turned quickly and laid a finger on his lips. Then the navigator gestured Dynamon toward a series of glass panels. There were six of these panels, each about a foot square, and ranged in two vertical rows of three each. One word, "periscopes," was stenciled at the top, and beside each mirror were other labels, "port bow," "port beam," "port quarter." The other three panels were labeled in the same way, designating their location on the starboard side. Borion flicked the switch beside the "starboard quarter" panel and it become dimly illuminated. Dynamon threw a swift glance at the altimeter, and saw that it said two thousand feet. Then he bent over and peered into the periscope panel. A wide panorama of twinkling lights spread out before him, the street lights of Copia. But the pale blue of approaching dawn was creeping fast over the city, shedding just enough light to reveal a dark shape a mile behind the Cosmos Carrier, and perhaps a thousand feet below. As Dynamon stared into the periscope screen, he thought he could detect a faint glow of red in the following shape. He turned questioningly to Borion. The navigator was writing rapidly on a piece of paper. A second later he handed the paper to Dynamon. It said:

"I queried Headquarters and was told that the conference with the Martian delegation is still officially going on. But that Carrier following us is bright red, the color of the Martian Carriers."

Dynamon held the piece of paper in his hand for a minute and gazed doubtfully into the periscope screen. Then he took the pencil from Borion and, bending over, wrote the following:

"I don't like the looks of this. Can we out-run them once we get out of the atmosphere?"

Borion nodded slowly.

"As far as I know, we can," he said, "unless—" he reached for the paper in Dynamon's hand and wrote "—unless they have developed a new wrinkle in their Carriers that we don't know anything about."

"Well," said Dynamon, "we won't waste time worrying about things over which we have no control. Proceed as usual."

There followed some anxious hours, which Dynamon spent with his eyes glued to the periscope mirror. In a short time the early golden rays of the sun appeared, and the Martian Carrier followed behind inexorably, glowed an ugly menacing crimson. Once Dynamon instructed his communications officer to speak to the Martian ship.

"Lovely morning, Mars. Where are you bound for?" was the casual message.

There came back a terse answer, "Test flight, and you?"

"We're testing, too," Dynamon's communications officer said. "We'll show you some tricks up beyond the stratosphere."

All so elaborately casual, Dynamon thought grimly. It was fairly evident that the Martian ship intended to follow the Earth Carrier to find out where it was going. Those inhuman devils! Why did the Earth's people ever have to come in contact with them?

Dynamon's thoughts went back to his childhood, to that terrible time when the men of Mars had abruptly declared war and descended suddenly onto the Earth in thousands of Cosmos Carriers. Only the timely invention of that remarkable substance, Geistfactor, had saved Earth then. It was a creamy liquid, which spread over any surface, rendered the object invisible. The principle underlying Geistfactor was simplicity itself, being merely an application of ultra high-frequency color waves. But it saved the day for Earth. The World Armies, cloaked in their new-found invisibility, struck in a dozen places at the ravaging hordes from Mars. The invaders, in spite of their prodigious intellectual powers, could not defend themselves against an unseen enemy, and had been forced to withdraw the remnants of their army and sue for peace.

But the unremitting jealousy and hatred of the little men with the giant heads for Earth's creatures was leading to new trouble. It enraged the Martians to think that human beings, whom they despised as inferior creatures, should have first thought of spanning the yawning distances between the planets of the solar system. It was doubly humiliating to the Martians that when they, too, followed suit and went in for interplanetary travel, they could do no better than to copy faithfully the human invention of the Cosmos Carrier. It was only too evident that Mars was gathering its strength for another lightning thrust at the Earth. This time, with the Photo-Atomic Ray, there was no doubt that they intended to destroy or subjugate Earth's peoples for good. And to that end the Martians had been inventing new bones of contention and had been contriving new crises. A peace-minded World Government had been trying to stave off the inevitable conflict with conference after conference. But to those on the inside it was only too evident that the Martians could invent pretexts for war faster than Earth could evade them.

Dynamon, watching the blood-red Carrier in the periscope mirror, felt a surging bitterness at the Martians. If they could only be reasonable, he reflected, if only they could be human, then he, Dynamon, would not now be floating away on a dangerous mission far from the Earth and the woman he loved. He tried to imagine what Keltry was doing at that moment. In his mind's eye he could see her on the stage of the Theater of Comedy, enthralling audiences with her youthful charm as she played a part in the latest witty comedy, or sang a gay ballad in a new revue.

He broke out of his reverie and tossed a glance at the altimeter. The needle was moving much faster now, climbing steadily toward seventy thousand feet.

"It's about time to go now, isn't it?" he asked Borion.

The navigator nodded. "Just about," he said, and put his hand on a lever marked "gravity repellor."

As the navigator pushed the lever smoothly forward, Dynamon turned back to the periscope mirror and saw the red ship behind suddenly dwindle in size. The new Cosmos Carrier was beginning to show its speed.

Apparently, the Martians were momentarily caught off guard. The red Carrier diminished to a tiny speck against the dark background of the Earth. But then it began to grow in size again as the Martians unleashed the power in their great magnets.

"Borion, how about friction?" Dynamon asked.

"We don't have to worry about that yet," was the answer, "we're not going fast enough. And the temperature outside is about sixty-five below."

Dynamon nodded and glanced again at the altimeter. The needle was steadily climbing, a mile every ten seconds. Once again he looked into the screen of the periscope. The Earth was now far enough away so that the young centurion could begin to make out the broad arc which was a part of the curving circumference of the globe. Silently he said a final good-bye to Keltry and turned to speak to Borion. At that moment the door of the control room burst open and an engineer stepped in and saluted the navigator.

"Stowaway, sir," the engineer said. "Just found her in the munitions compartment."

Dynamon stared out through the open door at the woman who stood out there between two soldiers.

It was Keltry.

It was a harried and heartsick centurion who, a few minutes later, called a conference in his own quarters. Borion and Thamon sat regarding him gravely, while Mortoch, the second in command, lounged against the wall, a faint, derisive smile on his lean face.

"We are faced with a situation," Dynamon said heavily. "I would like to hear some opinions."

"Flagrant case of indiscipline," Mortoch said promptly; "that is, if we can regard this impersonally."

"Personalities," said Dynamon sharply, "will have no influence on my final decision."

"In that case," said Mortoch harshly, "it seems to me, you are bound to put back to Earth and hand the woman over to the right people for corrective action."

"Good heavens!" cried Borion, "I hope we don't have to do that. We already have a problem on our hands in the shape of that Martian Carrier."

"What do you say, Thamon?" the centurion asked after a significant pause.

"Well," said the scientist quietly, "you can't altogether regard the situation without considering personalities. Keltry stowed away for a very personal reason, and one which it is hard to condemn entirely. I think we are over-emphasizing the official breach of discipline. I, personally, can't see that it makes so much difference. After all, we on this expedition are on our own and are likely to remain so for some time to come. I am in favor of going along about our business and forgetting how Keltry came aboard."

"Spoken like a civilian," said Mortoch sourly, "and I hold to my opinion. Just because Dynamon was promoted over my head, I see no reason for trying to curry favor with him."

There was an awkward silence during which Dynamon's face grew very pink and his blue eyes grew cold.

"I'm going to forget what you just said, Mortoch," he said. "You are a valued member of this expedition, and you are much too good a soldier to overlook the danger that lies in that kind of talk. Without my participation, you are out-voted two to one. We will not turn back."

He stood up with a gesture of dismissal and the three lieutenants filed out of the door. He paced the floor of his quarters for a few minutes, then walked to the door and gave orders for the prisoner to be sent in.

"Ah, Keltry darling," he said after the guard had left the two of them alone, "you have put me in an impossible position."

"I don't see why it should be that bad," Keltry answered. "It was an inhuman thing to do to separate us and I just wasn't going to permit it."

"Yes, but don't you see?" said Dynamon, "I will be accused of playing favorites because I don't turn around and take you back to Earth."

"I'm not asking favors," Keltry retorted calmly, "I just want to be a member of this expedition."

Whatever Dynamon was going to answer to that, it was interrupted by the loud-speaker booming:

"Centurion Dynamon is requested at the control room."

Dynamon leapt to his feet, crushed Keltry to him in a swift brief embrace and then opened the door.

"Escort the prisoner to the scientist's quarters," he ordered, "and release her."

Dynamon walked into the control room and saw that Borion's face was gray. The navigator was standing in front of the periscope screens looking from one to another. The centurion walked over and stood beside him.

"The Martians are showing their hand finally," said Borion. "They have decided that we're headed for another planet, and I don't think that they want to let us carry out our intention. See, here and here?" Dynamon peered into the port and starboard bow panels. He could see dozens of little red specks rapidly growing larger.

"They will try and surround us," Borion said, "and blanket our magnets with their own."

"That's not so good, is it?" Dynamon murmured. "What is our altitude from Earth?"

"Forty miles," was the reply, "and I think they still may be able to overhear our conversation."

"Let them," said Dynamon quietly, "We have no secrets from them and they may as well know that we're going to out-run them. Full speed, Borion!"

The Navigator advanced the "repellor" lever as far as it would go. There was a slight jerk under foot. Then he adjusted a needle on a large dial and moved the "attractor" lever to its full distance. There was another jerk as the great Carrier lunged forward through space. Borion smiled.

"I put the attractor beam on the moon," he said, "and we'll be hitting it up close to nineteen miles a second in a few minutes. We should walk away from those drops of blood, over there."

"Are we pointing away from them enough?" Dynamon asked. "What's to prevent them from changing their course and cutting over to intercept us? See, that's what they appear to be doing now."

The navigator peered critically at the forward periscope screens. "It may be a close shave at that," he admitted. "But please trust me, Dynamon, I'll make it past them."

The tiny red specks in the periscope screens were growing shockingly fast, indicating the frightful speed at which the Earth-Carrier was traveling. Bigger and bigger they grew under Dynamon's fascinated gaze. The centurion darted a glance at Borion. In this fantastic encounter, every second counted. Could the navigator elude the pursuing red Carriers? Borion haunched tensely over the control levers, his eyes glued to the screens. The Martian ships were as big as cigars now and tripling their size with every heartbeat. Dynamon clenched his fist involuntarily and fought down an impulse to shout a warning. That would be worse than useless now—the fate of the expedition was entirely in the hands of Borion.

Dynamon held his breath as a flash of red flicked across the port bow periscope screen. The Carrier heaved under his feet for a second then quickly settled to an even keel again. The sweat stood out in little drops on Borion's forehead.

"Too close for comfort," muttered the navigator. His eyes widened as another huge red shape loomed up in the starboard bow screen. Borion's hands flicked over a dial spinning a needle around. Then he hung desperately back on the repellor. There was a momentary shock. The Carrier seemed to bounce off something. Borion staggered and Dynamon hurled forward and crashed into the forward bulkhead of the control room.

Then Borion shouted, "We're through!"

Dynamon picked himself up off the floor with a rueful smile. "I thought we were all through for a minute," he observed.

"Well! That was a bad minute there!" said Borion excitedly. "I thought that one fellow was going to get us, but I kicked him off by throwing the beam on him and giving him the repellor. But you can see for yourself, they are far behind now, and they'll never in the world be able to catch up."

Dynamon peered into the port and starboard quarter screens and saw a group of rapidly diminishing red specks. He looked up with a sigh of relief.

"Good work, Borion," he said, and the navigator grinned.

"I don't think we will have to worry any more about the Martian ships from now on, if we're careful," Borion said. "I'm going to run for the shadow of the moon and from there I'll plot a course straight for Jupiter, avoiding Mars entirely."

The door to the control room opened, and a smiling, spectacled face peered in. It was Thamon, the scientist.

"That was quite a bump," Thamon observed. "Were we trying to knock down an asteroid?"

Dynamon gave a short laugh. "No, that was merely some of our friends from Mars trying to head us off. But they're far behind now and we don't anticipate any trouble for a good many days."

"Ah, round one to the Earth people," Thamon observed. "In that case, Dynamon, have you decided how you are going to conduct affairs within the Carrier in the immediate future?"

"Not quite," Dynamon replied. "Suppose we discuss that, in my quarters?"

Thamon nodded. "I'm at your disposal, Centurion."

Dynamon led the way down the little stair and into the compartment that served as his office. Once there, he threw off his long military cloak and sat down at a little table, his great bronzed shoulders gleaming in the soft artificial light.

"I suppose the first question," said Thamon, sitting down opposite the centurion, "is whether to institute suspended animation on board?"

"I think we'd better, don't you?" said Dynamon.

"It would save a lot of food and oxygen," the scientist replied. "You see, even at our tremendous rate of speed now, it will take two hundred and twenty-six days to reach the outer layer of Saturn's atmosphere. Until we actually land the ship, there is no conceivable emergency that couldn't be handled by a skeleton crew."

"Quite right," said Dynamon. "I'll have Mortoch take charge of the arrangements, if you will stand by to supervise the technical side."

"It's as good as done," said Thamon. "We have the newest type of refrigeration system in the main saloon. I can drop the temperature one hundred and fifty degrees in one-fifth of a second. By the way, I was a little worried by that outburst of Mortoch's when we were talking about Keltry."

"Oh, well," said Dynamon, "Mortoch is only human. He was a Senior Decurion and I was passed over him for this job. He couldn't help but be a little jealous. But he will be all right, he's a soldier, after all."

"I hope so," said Thamon, doubtfully.

"Why certainly," Dynamon affirmed. "As a matter of fact, I wish he had been given the command in the first place. Between you and me, I'm not too keen about this expedition to a comparatively unknown planet. Thamon, why on earth weren't human beings content to stay at home? Why did they have to go to such endless pains to construct these Cosmos Carriers? Before these things were invented, the inhabitants of Earth and the inhabitants of Mars didn't know that each other existed, and they were perfectly happy about it. But when they both began spinning around through space between the planets, all of a sudden the Solar System was not big enough to hold both Peoples."

"It's some fatal restlessness in the make-up of human beings," Thamon replied. "Do you realize how far back Man has been trying to reach out to other planets?"

"Well, the first successful trip in a Cosmos Carrier was made seventy-eight years ago," said Dynamon.

Thamon chuckled.

"As far as we know, that was the first successful trip," the scientist corrected. "As a matter of fact, the first Cosmos Carrier was anticipated hundreds of years ago. Just the other day in the library, I found a very interesting account of an archaeological discovery made up in North Central 3A—the island that the ancients called Britain. A complete set of drawings and building plans was found in an admirable state of preservation. The date on the plans was 1956, and as you will remember from your school history, all of North Central by that time had been terribly ravaged by the wars. The inventor, whose name was Leonard Bolton, called his contrivance a 'space ship.' Wonderful, those old names, aren't they? But the most remarkable thing of all, is, that the designs for that 'space ship' were very practical. If the man ever had a chance to build one, which he probably didn't, it might very well have been a successful vehicle."

"That's very interesting," said Dynamon. "Were there any clues as to what happened to Leonard Bolton?"

"None at all," the scientist replied. "All we know about him is that he designed the 'space ship' and then was presumably blotted out by the savage weapons used in the warfare of those days. But, as I say, the remarkable thing is that when we got around to building a Cosmos Carrier eighty years ago, we were able to use several of Leonard Bolton's ideas. Which all goes to show, I suppose, there's nothing new under the sun."

"I'm not so sure about that," said Dynamon with a smile. "I've an idea that we're going to bump into several things new to us on the planet Saturn."

"As to that," Thamon nodded, "I shouldn't be surprised if you are right. Now I suppose I'd better go and make arrangements for the refrigeration job. Will Mortoch be responsible for providing each individual with a hypodermic and return-to-life tablets?"

"That will be taken care of," said Dynamon. "I'll see you later."

Dynamon stood beside Borion in the control room, staring fascinatedly at the periscope screens. The images that were reflected in the six panels made up a composite scene that was awe-inspiring and fearsome. The great Cosmos Carrier was finally arriving at the end of its seven months' journey. In front of the Earthcraft, a vast, barren expanse, uniformly dark gray in color spread for thousands of miles. To one side of the Carrier a wide belt of mist and shimmering particles stretched upward from the planet out toward space. Dynamon realized that this was a small section of the great ring encircling Saturn, that could be seen in the powerful telescopes from Earth. Glancing at the stern vision screens, Dynamon saw the sun twinkling. So far away it was now, that it was hardly bigger than a large star and gave off not much more light. Even though they were coming to Saturn in the middle of a Saturnian day, there was no more than a gloomy half-light to illumine their way.

"Saturn revolves on its axis with such speed," observed Borion, "that I should imagine there will be tremendous prevailing winds on the surface. I think I can see a range of steep mountains down there; it might not be a bad idea if we landed in the lee of them."

"Yes," agreed Dynamon, "I think that would be a good idea. As a matter of fact, we may have to dig below the surface entirely to prevent being blown away. How is the gravitation pull?"

"It's a curious thing," Borion replied. "It should be tremendous but the centrifugal force is so strong that it counterbalances to a certain extent. The ship is handling very easily."

"How soon do you think we'll make the surface?" said Dynamon.

"I should estimate somewhere around six hours from now," the navigator answered. "I could make it sooner but I'm feeling my way."

"That suits me," said Dynamon. "That will give us just time to turn off the refrigeration and bring our people back to life. Lucky devils to be able to sleep through this trip—have you ever been so bored in your life?"

"Never," agreed Borion. "But I am not bored now."

Dynamon walked across the control room and threw a large switch in the wall panel.

"Decurion Mortoch and Scientist Thamon," he said into the loud-speaker system. "Proceed at once to remove the suspension-of-life condition in the main saloon. As soon as everyone is revived, stand by to take landing stations."

As the centurion closed the switch and turned away, Borion called him over again to the periscope screens.

"That is a range of mountains," said the navigator. "I can see it more clearly now. I think I'll slow up our descent a little bit so that by the time we're ready to land it will be midday again. As you probably know, Saturn makes a complete revolution in only a little more than ten hours."

"That sounds sensible," said Dynamon. "We'll need all the light we can get to make a safe landing."

Borion nodded and reached toward the repellor lever. He pushed it gently forward and then looked at his altimeter. He seemed to be dissatisfied with the altimeter reading and pushed forward the repellor lever a little more. Then he looked again at the altimeter, and an expression of bewilderment came over his face. With a muttered exclamation he jammed the repellor lever as far ahead as it would go, at the same time watching the altimeter. Dynamon sensed that something was wrong as he watched the color drain out of the navigator's face.

"The Saints preserve us!" the navigator cried hoarsly. "Something has gone terribly wrong—the repellor isn't working! We're dropping at a frightful rate of speed—!"

Borion leapt to the loud-speaker system and issued rapid orders to the navigating engineers.

"What's going to happen to us?" Dynamon demanded.

"I don't know," Borion said, his face ashen. "I think it is just a simple mechanical failure in the controls from the repellor lever down to the magnets. I don't know how soon my workers can discover the trouble and repair it. In the mean time—"

"In the mean time," Dynamon broke in gloomily, "we may all be spattered all over that gray landscape."

"Either that," Borion gritted, "or we burn to a crisp from the atmospheric friction. I can feel it getting warmer in here already."

Dynamon fought down the sickening sensation of panic that was starting to creep over him.

"How long do you think we have got?" he said with an effort.

"At the most," said Borion staring, white lipped, at the altimeter, "at the most, I should say a half an hour."

The door to the control room burst open and Thamon rushed in closely followed by Keltry.

"I heard you talking to your engineers, Borion," the scientist said rapidly. "Are we in trouble?"

"We are," said Borion, "and it may be the last trouble any of us ever have. Our repellor has gone out for some reason. And we're heading for the surface of Saturn like a meteorite."

"Can't anything be done?" said Thamon.

"My engineers are doing all they can to find the source of the trouble," Borion replied. "But until they do, I can't slow the ship up."

Keltry's great brown eyes were enormous as she moved over beside Dynamon and took his right hand in hers.

"As long as I'm with you, Dynamon," she said in a low voice, "I'm not afraid to die. But I hate to see your expedition fail. Perhaps the fate of the Earth depends on us here in this Carrier."

"I know," said Dynamon, squeezing her hand. His eyes followed Borion as the navigator went to the loud-speaker system again. But apparently the news from below was not encouraging, and Borion's shoulders sagged as he turned to face the other three people in the control room.

"They haven't found the source of the trouble yet," he said dully, "and there's not a thing to be done until they do. I'm sorry that, as navigator of this Carrier, I am plunging you all to your death. But it's a case of a simple mechanical failure which I couldn't foresee."

Keltry stepped forward impulsively and laid her hand on the navigator's wrist.

"Nobody could blame you, Borion," she said gently. "It isn't your fault if the attractor or the repellor lever, whichever it is, gets broken. You are already—"

"Wait a minute!" Borion shouted, eyes darting out of his head. "The attractor! In my excitement I forgot!"

The navigator leapt to the control levers, spun the dial and put his hand on the attractor lever.

"If—I'm only—on time!" he muttered agonizedly. "It's just possible—the counter-attraction of Jupiter—Lord it's hot!"

The control room was silent as death as the navigator eased the attractor lever carefully forward. Dynamon whipped a glance at the periscope screens. The ground was rushing up at a terrific rate, and out behind the Carrier, a dense cloud of black smoke was forming. The veins were standing out in Borion's forehead as he inched the attractor lever forward. The girl and the two men watched him with bated breath as he slowly raised his eyes to the altimeter. A wild incredulous expression appearing on the navigator's face.

"It's—it's working!" Borion muttered hoarsly, "the attractor beam from Jupiter is slowing us up!"

Dynamon's heart leapt and he sprang back to the periscope screens. The column of smoke behind them was still there but it seemed to be thinning out. But the surface of Saturn seemed to be rushing upward just as fast as ever. Dynamon twisted his head around to look at Borion. A feverish smile was lighting up the navigator's face as he pressed forward on the attractor lever.

"We may just make it!" he breathed, and Dynamon said a little prayer.

In the screen a range of dark gray mountains stood out in bold relief and seemed to reach claw-like peaks toward the speeding Carrier. But the smoke had ceased to whip past, and only a small black cloud far behind served to remind Dynamon of the fearful friction that the surface of the ship had been subjected to. At the same time Dynamon felt an invisible force dragging him toward the front bulkhead of the control room, and he knew that the Carrier was slowing up its forward speed. Through the bow periscopes the jagged range of mountains seemed so close that Dynamon almost felt he could reach out and touch them. Miraculously, they rose up to one side of the ship. A moment later a voice sounded in the loud-speaker system.

"The magnet room calling the navigator. A break in the control shaft has been discovered and repaired. Throw the repellor lever into neutral and then advance it."

Borion gave a little sob, flicked back the repellor and then pushed it forward again. The floor of the control room heaved for a minute and then settled on an even keel, Dynamon stared unbelievingly at the starboard midship's periscope screens and saw that the great Carrier was resting immobile not more than twenty feet above the gray soil of Saturn.

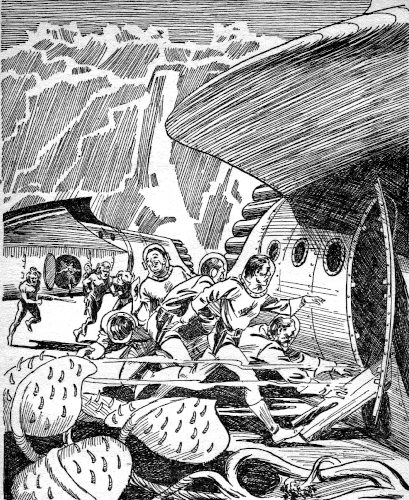

"Saved!" cried Borion hysterically, "and it was Keltry who did it! In my excitement I would have let all of us plunge to our death, if Keltry hadn't reminded me that there was such a thing as an attractor lever! Dynamon, Thamon, we should get down on our knees and thank our stars that Keltry was in here!"

The door of the control room opened and Mortoch stepped in.

"Do you have to toss us around like that?" the lean decurion said. "I had a near-panic on my hands with some of those people just coming out of their suspended animation. Oh!—" Mortoch smiled ironically—"I begin to see why we had such a rough passage. If beautiful stowaways are given the run of the control room, I should imagine it would be hard for the navigator to keep his mind on his work."

Borion started forward with a snarl but Dynamon's voice cracked like a whip.

"Attention! Both of you! Try and remember that you are modern, civilized men, not twentieth century brutes."

Borion's hands fell to his sides, and he began to laugh.

"You're absolutely right, Dynamon," he said, "I don't know why I should let myself be annoyed by this crude soldier. After all, the cream of the joke is that Mortoch would never have been able to come in here and make sarcastic remarks about Keltry, if Keltry hadn't been here for the past half hour."

"What do you mean by that?" said Mortoch suspiciously.

"I mean," said Borion, "that if Keltry had not been in here, you and everybody else aboard this Carrier would now be dead."

"Now!" said Dynamon. "I think we have had enough of personalities. Suppose we get a little work done. Mortoch, prepare the First Decuria for reconnaissance duty. Each man should be equipped with cloak, oxygen mask, counter-gravity helmets, and a supply of voltage bombs, and each man's radio should be set at eighty-one thousand meters. Have them ready at the main door in fifteen minutes. I will lead them on a short tour of exploration and Thamon will accompany me. In the mean time, Mortoch, you will remain in charge of the Carrier until I get back."

Dynamon's heart was pounding with excitement as he and Thamon walked through the main saloon toward the group of cloaked figures standing by the big round door. As far as he knew he was going to be the first human being ever to step foot on the planet Saturn. He mentally checked over his own equipment and made sure that it was all in place, including the hard rubber box slung over his shoulder on a strap. That box contained his supply of voltage bombs—little glass spheroids, smaller than golf balls, which, when hurled at an enemy, burst releasing a tremendous electric charge. There was little likelihood that these bombs would be needed, because the periscope screens had shown no sign of life anywhere in the gray, arid valley in which the Cosmos Carrier was lying. However, Dynamon was taking no chances. He glanced briefly at Thamon beside him. The scientist was unarmed, carrying the light metal staff which was the badge of his profession.

Dynamon stepped forward and ran his eyes quickly over the masked, muffled figures of the First Decuria. Then he signed to an engineer who quickly unfastened the great door. Dynamon then stepped through and his party followed him crowding into the air lock between the inner and outer doors. Thamon stepped forward, maneuvered a lever, the outer door swung open and Saturn lay waiting for the touch of Dynamon's foot.

It was not an especially inviting prospect. A blast of unbelievably cold air swirled through the open door, carrying with it particles of fine, gray sand. In the dim, murky twilight, tall gray mountains loomed ominously across the valley floor. Dynamon shivered and turned up the heat in his electric cloak. Then with one hand on the knob of his counter-gravity helmet he stepped gingerly out on to the ground.

Instantly he sank to his knees in gray sand that was as light and powdery as fresh snow. With a quick twist of the knob on his helmet he kicked his feet free and stood lightly on the surface again.

"Attention, First Decuria!" he said into the transmitter of his radio phone. "Adjust counter-gravitation to approximately plus ten pounds."

Stepping backward, he turned and watched the masked figures of his command leave the Carrier one by one. Thamon came out first, followed by the Decurion, and after him the soldiers. Mechanically, Dynamon counted them. As the tenth soldier stepped out on the gray soil, Dynamon started to turn away when to his astonishment an eleventh cloaked figure came out of the door of the Carrier.

"Decurion!" Dynamon said sharply into his transmitter, "since when have you had eleven men in your command?"

"Never," came back the prompt answer in Dynamon's ears. As the decurion faced about to count his men, one of them moved over beside Dynamon.

"Forgive me, Dynamon," came a soft feminine voice, "but I had to come with you. It's Keltry. Please don't send me back, I promise not to be any trouble."

Dynamon hesitated, then reluctantly agreed to allow her to come along.

"Stay close to Thamon," he warned, and started off down the valley, the rest of the party following him.

Lightened as they were to keep from sinking deep into the treacherous powdery sand, the humans made fast progress, accelerated by the strong breeze that blew at their backs down the valley. At that, Dynamon realized that the lofty mountains on either side provided protection against immeasurably stronger winds higher up. From the saw-toothed peaks on the left, dark streamers of sand stood out for yards, indicating constant winds of gale proportions up there.

The valley itself, as far as Dynamon could see in the dim half-light, was barren of any kind of life. There was no sign of a creeping, crawling, or flying creature; nor was there any vegetation, trees or grass. Dynamon led his column nearly a mile down the unchanging gray of the valley and then called a halt.

"Thamon," he said, beckoning the scientist to him, "can you see any possibility of human habitation in this valley?"

"Off-hand, I don't, not on the surface," the scientist replied. "I would have to test the atmosphere for oxygen, but I doubt if there is a large enough proportion. My guess is that there is nothing but nitrogen in this air. That won't support human life, or any other kind of life except possibly certain kinds of plants."

"What about tridium?" said Dynamon. "How do you go about looking for it?"

"Electrophysiological tests of all kinds," said Thamon. "I must say this valley doesn't look very encouraging. It looks like burned out volcanic ash. Say! What's that up the valley?"

Dynamon gazed back in the direction of the Cosmos Carrier, and felt an uneasy prickling along his spine. The desert valley floor behind them seemed suddenly to have sprouted some tall bushes. There were possibly a dozen of them standing at intervals of twenty yards. They were too far away—perhaps one eighth of a mile—for Dynamon to see them very well, but they appeared to consist of a score of leafless branches radiating outward in all directions from a small core. It was as if a basket ball was bristling with ten-foot javelins.

"Where did they come from?" Dynamon gasped. "I didn't see them when we walked over that ground a few minutes ago."

"Nor I," agreed Thamon. "I can't imagine where they came from."

Just then one of the bushes apparently moved a few feet as if blown by the wind.

"Good Lord!" exclaimed Thamon. "Did you see that? One of those things rolled forward!"

Then another of the fantastic bushes started to roll, and another, and another. In a moment all twelve of the extraordinary apparitions were rolling rapidly down the wind toward the humans. Dynamon felt the hair on the back of his neck stiffen, and he sprang into action, commanding his soldiers to converge around him.

"Thamon, what are those things!" Dynamon cried.

"I don't know," the scientist replied. "I don't think they can be animals. But they might be rootless nitrogen-feeding plants of some kind. Look! Those branches are covered with long thorns!"

The fantastic creatures were rolling swiftly down on the little group of humans, and Dynamon could see the sharp thorns around the end of each branch. He reached into the box at his hip.

"Decuria, ready with voltage bombs," he commanded, and looking around saw that each man held one of the little glass bombs in his hand. The bushes were only fifty feet away now, rolling lightly over the gray sand on their spindly branches.

"Ready?" warned Dynamon, "throw!"

A shower of glistening glass balls flew through the air into the midst of the menacing apparitions. There was a series of blinding flashes and loud reports. Some jagged white lines appeared among the black branches of the monsters, but they kept right on rolling downwind. Dynamon felt a surge of dismay. Those voltage bombs had been, for years, Man's best weapon.

"They're plants all right!" came Thamon's voice. "You can't kill them with electricity any more than you can kill a tree!"

Dynamon looked at the men huddled about him and thought quickly.

"All we can do, men, is to try and dodge them," he announced. "Spread out and as soon as one of those things passes you run upwind! Keltry! Thamon! Stay close to me."

The line of rolling bushes was almost upon them as the soldiers deployed in all directions. Seizing Keltry by the hand, Dynamon leapt to one side dragging her out of the path of one of the spiney monsters. Thamon gasped a warning, and Dynamon, turning his head, felt a thrill of horror as he saw another of the creatures almost on top of them. Acting instinctively, Dynamon snatched the metal staff from Thamon's hands and flailed frantically at the black, thorny branches. To his amazement, they shivered and snapped under the metal rod like matchwood. Hardly daring to believe his eyes, Dynamon struck again and again at the horrible creature, until in a few minutes it was nothing but a pile of scattered, broken faggots on the gray sand.

But cries for help and screams of anguish sounded in Dynamon's ear phones, and he saw that five of the soldiers were on the ground impaled on the cruel thorns of others of the monsters. He ran toward them and beat them to pieces with the rod but too late to save the lives of the men. They lay pierced in a dozen places by long, black thorns. The rest of the Decuria had managed to dodge the whirling branches of the other bushes and now stood safely up wind of them. Dynamon summoned the survivors around him.

"What do you think, Thamon?" he asked. "In your opinion are there likely to be more of these horrible things around?"

"There may easily be," the scientist replied promptly. "But since the only defense against them is this one metal rod, I recommend that we leave our unfortunate comrades here and head immediately for the mountains over there. Those poor fellows are beyond our help and we should be able to find better protection from these blood-thirsty thorn-bushes among the foot hills. When we get there we can work upwind until we're opposite the Carrier again."

"That sounds like good advice," said Dynamon. "And we'll act on it. It's getting so dark now that we couldn't see to protect ourselves if any more of those creatures came rolling down the wind. Everyone join hands and follow me."

After a nerve-racking march of about twenty-five minutes through the gathering darkness, the party of nine humans felt the ground rising beneath their feet. Dynamon halted and hurled a voltage bomb forward and upward. As the bomb exploded, the momentary flash revealed to the party that they were at the foot of a steep, rock-strewn declivity. Dynamon led the party upward, feeling his way over the great boulders. After a few minutes of climbing, he called another halt and again threw a voltage bomb.

"We'll stay here for a few hours," the centurion announced, "until it gets light enough to see our way. We will be safe in the lee of these big rocks, so make yourselves comfortable."

Nine dim figures spread out on the sloping ground. Then one of them drifted apart from the rest, up hill.

"Who is that?" Dynamon demanded.

"Keltry," came the answer. "I am just going up hill a little distance. When you exploded that last bomb I thought I saw something that looked like the edge of a volcanic crater."

"You can't see anything in this darkness," said Dynamon. "Wait till it gets light again before you do any exploring."

"Oh, I won't go far," said Keltry. "Really, I won't."

"Well, be sure that you don't," Dynamon smiled into his transmitter. Then he said, "Thamon, where are you?"

"Right here," and a figure moved over beside the centurion.

Dynamon's question was casual.

"Did you see anything that looked like a volcanic crater?"

"Come to think of it," the scientist replied, "I think I did. It's just up here a few yards."

"Shall we go along and have a look at it too, then?" said Dynamon, getting up on his feet. Just then, he stood rooted with horror as a piercing scream rang in his ear phone.

"Dynamon! Dynamon, I'm falling!"

"Keltry!" the centurion exclaimed. "What's the matter? Has something happened to your helmet?"

"Yes!" Keltry's voice was fainter. "I've lost it! It was unfastened, and when I stumbled, it rolled off!" Fainter and fainter grew the voice. "I'm falling down a black hole a mile a minute!" With a muttered sob, Dynamon scrambled up the slope. A moment later, his foot stepped out on empty space. He started to fall into nothingness.

"Keltry!" he cried into his transmitter. "Where are you? Answer me!"

Straining his ears Dynamon heard a tiny voice far away saying, "I'm still falling."

"I'm coming after you, Keltry!" the centurion yelled, and reaching up to the knob on his helmet, twisted frantically. By doing that, he multiplied the gravitational pull of the planet and was now falling much more swiftly than Keltry. How deep this black pit was, Dynamon had no idea, but he prayed it would be deep enough so that he could catch up with Keltry before she hit the bottom. It was a desperate chance but Dynamon was willing to take it.

"Keltry!" he shouted into the transmitter. "Can you hear me? I'm coming for you."

"Yes, I hear you, Dynamon," came the answer, and Dynamon's heart leapt as it seemed to him that the voice sounded a little stronger.

"Keep your courage up, Keltry," he said, trying to sound calm. "I'm falling faster than you are. There doesn't seem to be any bottom to this pit so I'm bound to catch up with you."

"Oh, Dynamon! You shouldn't have jumped after me. There's—there's only—one chance in a million that we don't crash."

Keltry was bravely trying to hide the despair and terror in her voice, but most important of all to Dynamon was the fact that she sounded—still nearer! He resolutely put out of his mind the frightful probability that at any second, first Keltry and then he, would be dashed to pieces at the bottom of the pit. It seemed to him that he had been falling for miles, and he thought that there was beginning to be more air resistance now. He bent his head and peered downward, trying to pierce the inky blackness with his eyes, but he could see nothing. It was a fantastic sensation or, better still, a lack of all sensation. He seemed to be resting immobile in a black nothingness, with only the rushing air tearing at his cloak to indicate that he was falling.

"Keep talking, Keltry," he cried.

"Oh, you sound so much nearer!" There was a note of incredulous hope in Keltry's voice.

"I told you I'd catch up with you!" Dynamon exulted.

Suddenly, his heart gave a great bound. He was still peering downward and it seemed to him that far away he could see a tiny pin point of light.

"Keltry!" he cried, "am I seeing things? Or is there something that looks like a star; way down there?"

"Oh, I think I see it!" Keltry answered breathlessly. "Dynamon, what could that mean?"

"I don't know," said Dynamon, "but it seems to be growing larger, and I'm getting much nearer to you."

Under his fascinated eyes, the star grew bigger and brighter by the second. In a few moments Dynamon, hardly daring to believe his eyes, thought he could make out the outlines of a flying figure between him and the light.

"Keltry!" he shouted. "I've almost caught up with you! Hold your hands up over your head."

"Oh Dynamon! I think I can see you."

The point of light which Dynamon thought was a star, was growing into a larger, brighter disk. Keltry's body was sharply outlined against it now, and she seemed to be scarcely ten feet away. Dynamon bent himself into a jack-knife dive and kicked his feet up behind him. The air pressure was tremendous now, and Dynamon began to realize that it was no star, or sun, or planet down below but the bottom of the pit. Rays of light spread upward, illuminating the smooth, shiny sides of the shaft. A few more agonizing seconds went past and Dynamon's hands grazed the tips of Keltry's upraised fingers. Dynamon dared not estimate how far above the bottom of the pit they were, but concentrated on gaining the few inches he needed to get a grip on one of Keltry's wrists.

"We've—almost—made it!" he panted. "Here—grab my right arm and hang on for dear life!"

An involuntary shout of relief came from Dynamon's lips as he felt Keltry's strong fingers close over his arm.

"Hang on!" he shouted, and his left hand flew up to his helmet and carefully turned the counter-gravitation knob. At the same time, he twisted his back around and fought his feet downward. A moment later, he gripped Keltry's torso under the arms with his knees. Frantically, he tried to estimate how far above the bottom of the pit they were. They might be five thousand feet—or five hundred feet. Slowly he turned the dial on his helmet, resisting the almost insuperable impulse to twist the knob too fast. If he tried to stop their fall too quickly it would tear their bodies apart.

Slowly, ever slowly, the air-rush diminished. By now, they were well down into the area illuminated from the bottom of the pit. And they could see that they were falling through a round shaft perhaps one hundred feet in diameter. Dynamon judged that they were less than one hundred feet off the bottom.

"Look out, Keltry," he said. "I've got to put on the brakes hard."

He gritted his teeth, and flicked the knob on his helmet. He stifled a groan as invisible ropes attached to his feet and hands seemed to be trying to pull him apart. But gradually the terrific pressure released. He moved the knob a shade, and released the grip of his knees on Keltry.

"There!" he grunted as they both landed lightly on solid ground. "There wasn't two seconds to spare."

Keltry drew a shuddering sigh and put a hand on Dynamon's arm for support.

"Oh, Dynamon!" she whispered, "if I weren't such a well brought-up girl I would break down and cry from sheer relief."

"I don't blame you," said Dynamon in a voice that shook a little. "That was quite an experience, but we came out of it all right. Now, where do you suppose we are? How do you suppose this pit was ever formed?"

The two Earth-people stared around them curiously. They were bathed in a bright light, and yet there was no apparent source of illumination. It began to dawn on them that the rocks which formed the side walls at the base of the shaft, were themselves luminous, glowing with a curious greenish light. Dynamon tilted his head back and stared up into the darkening shaft. Suddenly, he uttered an exclamation and, seizing Keltry by the wrist dragged her to one side. A few seconds later, a round object dropped out of the shaft and bounced on the ground. It was Keltry's counter-gravity helmet.

Dynamon reached down and picked it up. "It's a good thing that these things are well built," he remarked with a smile, "or this would be smashed to bits. The knob is still set for plus ten pounds, and that was quite a fall. I wonder whether it still works."

He twisted the knob experimentally and the helmet started to sail upward.

"Say!" Dynamon cried. "It works, all right! Here, put it on Keltry."

Keltry accepted the helmet with a laugh, put it on her head and was buckling it under her chin when her blood suddenly congealed in her veins. A loud shout rang echoingly through the shaft. Dynamon whirled around and beheld a curious figure standing in front of a rock not sixty feet away. It stood upright on two legs, and cradled a sort of club in its arms. Its head was covered with long, yellow hair that fell down on to its shoulders, and the lower half of its face was covered with coarse, yellow hair. Blue eyes glinted from under shaggy brows in a menacing glare at the two Earth-people.

"It looks quite human, doesn't it?" whispered Keltry.

Dynamon nodded and slid his ear phone off his right ear as he saw the stranger's hairy mouth opening and closing. Keltry followed his example in time to hear the stranger's rumbling voice.

"Whoo-yoo?"

Dynamon touched Keltry's hand. "That sounded like 'who are you' didn't it?" he said wonderingly.

"It certainly did," Keltry answered. "I think that's some kind of human."

"If it's a human," Dynamon said, "then there must be some sort of breathable atmosphere down here. You notice he's not wearing any oxygen mask."

"Whoo-yoo?" the stranger repeated, "an whey cum fum?"

"He's speaking a kind of English!" said Keltry excitedly. "He said, 'who are you' and 'where do you come from'!"

"By Jupiter!" cried Dynamon. "I think you're right. If he can breathe without a mask, so can we. I'll have a little talk with him."

A moment later the centurion stood bare-headed, helmet and oxygen mask in hand.

"We're humans from Earth," he told the stranger, pronouncing each word carefully. "Who are you?"

The stranger's eyes and mouth flew open in astonishment and the rod sagged in his hands.

"Humes! Fum Earth!" he cried hoarsely, then turned his head, and gave an ear-splitting yell.

A moment later, a dozen or more short, hairy-faced creatures closely resembling the first stranger came tumbling through a passageway behind him and stood rooted with astonishment at the sight of Dynamon and Keltry. Their bodies were completely covered, the torsoes, with loose, gray tunics, and the legs with ugly, baggy tubes. They advanced cautiously on the two people from Earth.

"Take off your helmet and mask," Dynamon directed Keltry, "the air is perfectly good. We'll try and find out the mystery of how these humans ever got here."

He turned and addressed the first stranger, again enunciating slowly and carefully. Immediately the whole crowd burst into excited jabbering. Here and there Dynamon thought he recognized a word. Finally, one man taller than the rest stepped forward.

"Yoo cum thus," he declared.

"Certainly," Dynamon nodded with a smile, and reached out a hand to Keltry. The crowd, with wondering eyes, opened up a line and the two young people from Earth followed their self-appointed guide through it. A short narrow passageway led off at a sharp angle through the rocky wall of the pit, and presently Dynamon and Keltry found themselves on what appeared to be a hill top. Both of them gave little gasps as a vast and magnificent panorama spread out before their astonished eyes. It was as if they had stepped into a new world.

A gently undulating plain stretched away in three directions as far as their eyes could see. It was predominantly gray in color, but here and there, were scattered long, narrow strips of green. These green strips all had shimmering, silvery borders, and Dynamon couldn't help recalling to mind some arid spots back on the Earth that were criss-crossed with irrigation ditches. There were no trees on this vast plain, but strewn around in a haphazard way, were a quantity of great boulders. And these rocks, like the rocks at the base of the pit, glowed luminously. However, the landscape was clearly illuminated by some other source than those scattered rocks. Dynamon lifted his eyes upward and saw that above them, and stretching as far as the eye could reach, there was a softly luminous ceiling. There was no way of telling how high up this ceiling was. It might be twenty feet or twenty miles. The effect was like that of certain days on the Earth, when wide-spread clouds blanket the sky and diffuse the sun's rays.

The plain was by no means deserted. Here and there along the green strips four-legged creatures moved slowly, creatures that, on Earth Dynamon would have said were cows. Nearer at hand, a flock of small white creatures milled around aimlessly, and Dynamon could have sworn he heard the cackle of hens. Dynamon glanced over his shoulder and saw that the little hairy-faced men were filing out of the passageway to the pit. The guide tugged at his sleeve.

"This oo-ay," he said and pointed to his right.

Still holding Keltry's hand, Dynamon turned and followed the man, and the others fell in behind them. Their way eventually led toward a tall set of cliffs at the base of which a score or so of cave-like openings could be seen.

"These are humans, aren't they, Dynamon?" Keltry whispered.

"They certainly look like it," Dynamon answered, "although obviously they're very primitive."

"Then how and when did they come to Saturn?" Keltry persisted.

"I haven't the faintest idea," Dynamon shrugged. "Perhaps we'll find out."

Other strange humans came running up the hill and joined the crowd behind them. Apparently they were not all men, for some of them had no hair on their faces and wore long robes over their bodies. The guide led them straight to one of the openings in the cliff, then halted and faced the two adventurers impressively.

"The koo-een!" he announced in a loud tone.

Dynamon and Keltry looked wonderingly at each other and then back to the guide. At that moment a woman appeared at the mouth of the cave. She was small and delicately formed and strikingly beautiful. She had the bluest of eyes and golden hair that fell away on either side of a marble brow. A long-sleeved white garment gathered at the waist covered her from neck to toe, but its shapeless folds could scarcely conceal the delicious curves of her little body.

"Humes!" the guide shouted proudly, "fum Earth!"

The woman's blue eyes widened as she stared solemnly at Dynamon and Keltry.

"Are you from Earth?" she said in slow musical tones. "So strange! So wonderful! How did you come?"

Dynamon grinned. "We came in a Cosmos Carrier," he said easily. "And to us, it seems even more strange and more wonderful that we find humans already on Saturn."

A shy answering smile came over the woman's beautiful face.

"We have been here hundreds of years," she replied in the same slow accents. "But come inside the Palace and we will talk."

She turned with an inviting look and the two adventurers from Earth followed her through a passageway lined with the, by now, familiar luminous rocks. They came out in a fairly large, high-ceilinged room, in the center of which was a sort of table made out of a long, trimmed slab of rock. At one end of this table was a high-back chair made of woven reeds. The woman walked over to the chair and sitting down in it, indicated stools on either side of her.

"Sit down," she said, "and tell me more about yourselves."

"Thank you," Dynamon answered, and turning to his companion said, "It's warm in here, I think we might take off these cloaks."

Keltry nodded, and putting her hand to the throat fastening, zipped it downward. Dynamon did likewise and the two stepped out of their cloaks. There was a sudden scream from the beautiful little woman, and her hands flew up in front of her eyes.

"What are you doing?" she squealed. "Why you're—you're practically naked! You're positively immodest!"

Keltry threw a startled glance at Dynamon's long, brown legs.

"Why, not at all," she said quietly. "We are dressed like everyone else on Earth at the present time. Modesty with us, nowadays, is something much more important than lengths of cloth."

The little woman kept her hands before her eyes and shook her head vigorously. "It's immodest," she insisted, "and you must put on your clothes at once. Don't you realize that I'm the queen?"

Reluctantly, Keltry and Dynamon stepped back into their heavy cloaks and zipped them up the front.

"Well! that's better," said the little queen primly. "My goodness," she said with a slight glance, "is everybody on Earth as big and brown as you two?"

"We're about average, I should say," Keltry answered with a smile. "And seriously, we didn't mean to offend you in the matter of clothes."

"Well we, on Saturn," said the little queen, "don't believe in indecent exposure. Now, you say you came in some kind of a carrier?"

"Yes," said Dynamon. "It's up on the surface. We were exploring in the darkness and fell down the long shaft."

"Why weren't you killed?" said the queen, blue eyes wide. Dynamon explained the counter-gravity helmets. It took considerable explanation, because the queen was inclined to disbelieve the whole story. She finally accepted it, however, and then launched into a long series of questions about the Cosmos Carrier and about the state of the Earth. Eventually Dynamon found an opening and started asking questions on his part.

"We're anxious to know about you and your people on Saturn," he suggested. "Have you a name or are you addressed only as Queen?"

"I am Queen Diana," the little woman stated. "The last of my line. I am a Bolton, and the Boltons have been rulers of Saturn ever since we came here."

"Bolton!" Dynamon shouted. "Are you a descendant of Leonard Bolton?"

"Yes!" replied the queen, with a delighted smile. "Do they still remember Leonard Bolton on Earth?"

"We know that he designed a contrivance called a 'space ship', but that's all. Did he actually build such a ship, and is that how you come to be here so many thousands of miles from Earth?"

"Yes," said Queen Diana, proudly. "It's all down in some books which I will show you. Leonard Bolton built a space ship which was big enough to hold ten families and their belongings. There was a terrible war going on and he thought the only place to find safety was another planet. So the 'space ship' left the Earth by means of a thing called a 'rocket,' whatever that is. And they wandered around for years in space till they finally came into Saturn's orbit, and the tremendous gravity pulled the ship right through the light outer crust into this Nether World. I don't know how many years ago that was, but we have been here ever since."

"Well that is an amazing story," said Dynamon. "And I would like to see those books you mentioned. How incredibly fortunate that the 'space ship' broke through into this Nether World, where there is an atmosphere that will support life. And it is pretty miraculous too, that the 'space ship' didn't break up from the force of hitting the outer crust."

"Well, the books say that it was broken up somewhat," the queen answered, "but nobody was hurt. And after they unloaded the ship, they took it apart so that they could use the metal in it for other things."

She was eyeing him admiringly.

"And the colony has survived over a thousand years," Dynamon mused. He could not help thinking how, in comparison with the people on Earth, the survivors of Bolton's expedition were a rather poor lot. They had made no progress at all in the thousand years, mentally or culturally; from all evidences they had, on the contrary, retrogressed at least to a degree. Then across his mind flitted a picture of the hardships these brave souls had to endure in establishing themselves on the new planet. At no time could they have even hoped to return to Earth.

With their limited equipment they had set out to make the most of their new world. The great caves offered natural shelter so it was small wonder that they made their homes in them.

Dynamon, although a soldier to his finger tips, had none of the haughtiness and cruelty which are so often found in the warriors of today. Quickly his pity for the colonists turned into admiration, and he turned gently to face Queen Diana again.

"Tell me," he asked, "Are we the first strangers you have seen? You haven't, by any chance, been visited by Martians, have you?"

"Martians," said the queen. "What are they?"

"At present, they are just about the worst enemies of human beings," Dynamon replied tersely.