Venus was civilized ... so the Universe thought! But

deep in its midnight caverns ... beyond light, beyond

the wildest imaginings of an ordered System ... dwelt Horror.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1940.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

They stood in the Orestes' tiny observation turret, Mallory's defiant arm still tight about the slim and lovely girl, just exactly as bull-voiced Captain Lane had found them. The shimmering reflection of the planet Venus, only a few thousand miles ahead, bathed the trim, hard-jawed man and the softly pretty girl in a gentle glow, but it failed to soothe the grizzled space ship skipper.

"What in hell does this mean?"

Mallory, remembering an old forgotten saying—something about a soft answer turning aside wrath—spoke rapidly. "Sorry if we gave you a shock, sir," he said. "But your daughter and I are engaged."

Few medical men would have guaranteed Space Captain Jonathan Lane a long life at that moment. His usually ruddy face was a violent mauve-scarlet, his eyes hot pin-points of anger, his lean, hard body was atremble with emotion.

"Engaged. Engaged!" He made a convulsive motion. "Did you say engaged? To this inane young fool. You're talking nonsense. Go to your cabin, girl."

Dorothy Lane sighed and looked hopefully up at Mallory.

Tim Mallory had forgotten his old and wise quotation.

"Why not engaged," he snapped. "What have you got against me?"

"What," growled Captain Lane. "He asks me what!"

He had a reason; one which he shared with all fond parents who have ever seen a beloved child slipping from their arms—jealousy. Jealousy and grief. Now his mind pounced on a substitute for the true reasons that he would not—could not—name.

"Well, for one thing," he said curtly, "you're not a spaceman. You're nothing but a blasted Earthlubber!"

Mallory grinned.

"You can hardly call me an Earthlubber, Captain. I spent two years on Luna, three on Mars; I'll be five or more on Venus—"

"Pah! Luna ... Mars ... Venus ... you're still a groundhog. I'll not see my girl married to a money-grubbing businessman, Mallory."

"Tim's not a businessman," broke in Dorothy Lane. "He's an engineer." And anyone seeing her young fury would have smiled to note how much alike she was to her bucko, space captain father.

"Engineer! Nonsense! Only an astrogation engineer deserves that title. He's a—a—What is it you do? Build ice-boxes?"

"I'm a calorimetrical engineer," Mallory answered stiffly. "My main job is the designing and installation of air-conditioning plants where they are needed. On airless Luna, the cold Martian deserts, here on Venus. The simple truth is—"

"The simple truth is," stated the skipper savagely, "that you're a groundhog and a damned poor son-in-law for a spaceman. You being what you are, and Dorothy being what she is, I say the hell with you, Mr. Mallory! Perhaps I can't prevent your marriage. But there's one thing I can do—and that is wash my hands of the two of you!"

He watched them, searching for signs of indecision in their eyes. He found, instead—and with a sense of sickening dread—only sorrow. Sorrow and pity and regret. And Tim Mallory said quietly, "I'm sorry, sir, that you feel that way about it."

Lane turned to his daughter.

"Dorothy?" he said hoarsely.

"I'm sorry, too." Her voice was gentle but determined. "Tim is right. We—" Then her eyes widened; sudden panic lighted them, and her hand flew to her lips in a gesture of fear. "Something's wrong! Venus! The ship—!"

Captain Lane did not need her warning. His space-trained body had recognized disaster a split-second before. His legs had felt the smooth flooring beneath him lurch and sway. His eyes had glimpsed, through the spaceport, the sudden looming of the silver disc toward which they had been gliding easily but now were plunging at headlong, breakneck speed. His ears howled with the clamor of monstrous winds that clutched with vibrant fingers the falling Orestes.

In a flash he spun and fought his way up a sharply tilting deck to the wall audio, thrust at its button, bawled a query. The mate's voice, shrill with terror, answered:

"The Dixie-rod, sir! It's jammed! We're trying to get it free, but it's locked! We're out of control—"

"Up rockets!" roared Lane. "Up rockets and blast!"

"They're cut, sir! The hypo's cold. We'll have to 'bandon ship—."

Abandon ship! Tim Mallory did not need Dorothy's sudden gasp to tell him what that meant to the trio caught in the observation turret. Earthlubber he might be, but he knew enough about the construction of space craft to realize that there were no auxiliary safety-sleds anchored to this section of the Orestes.

Venus was no longer a beaming platter of silver in the distance. They had burst through its eternal blanket of cloud, now; The world below was no longer a sphere, it was a huge saucer of green, swelling ominously with each flashing second. Tempests screamed about them, and the screaming was the triumphant cry of hungry death.

No ships. No time to seek escape. Life, which had but recently become a precious thing to Tim Mallory, was but a matter of minutes.

He saw the agony of indecision on Captain Jonathan Lane's face, heard, as in a dream, the skipper delivering the only possible order.

"Very well, Carter! 'Bandon ship!"

And the pilot's hectic query, "But where are you?"

"Never mind that. Cut loose, you fool!"

"No, Captain! You're below. I can't let you die. I'll keep trying—"

"'Bandon ship, Carter! It's an order!"

And the faint, thin answer, "Aye, sir!" Silence.

Tim turned to Dorothy, and from somewhere summoned the ghost of a smile. His arms went out to her, and as one in a dream she moved toward him. There was, at least, this. They could die together.

And then Captain Lane was between them, bellowing, commanding, pushing them apart.

"Avast, you two! This is no time for play-acting. Mallory, jerk down those hammocks. Tumble in and strap yourselves tight! It's a chance in a billion, but—"

Tim swung into motion. The old man was right. It was a slim chance, but—a chance! To strap themselves into the pneumatic hammocks used by passengers at times of acceleration, hope that by some miracle the Orestes would not be crushed into a metal pancake when they crashed, pray that it might land on a slope, or some yielding substance.

It was a breathless moment and a mad one. Frenzied winds and the groan of scorching metal, the thick panting of Captain Lane as he strapped himself into a hammock between Tim and Dorothy, Dorothy's voice, "Tim, dear—" And his own reply, "Hold tight, youngster!"

Then heat increasing, heat like a massive fist upon his breast, hot beads of sweat, salt-tasting on his lips, an ear-splitting tumult of sound from somewhere.... A swift, terrifying glimpse of solid earth rushing up to meet them.... The last, wrenching shudder of the Orestes as it plunged giddily groundward. Heat ... pain ... flame ... suffocation....

Then darkness.

Out of the darkness, light. Out of the sultriness, a thin, cool finger of breeze. Out of the silence of death, life!

Tim Mallory opened his eyes. And a thick, wordless cry of thanksgiving burst from his lips as he stared about him. The impossible had happened!

The ship had crashed. Its control-room was a fused and twisted heap of wreckage smoldering in the giant crater it had plowed. But somehow the observation turret, offset in a streamlined vane of the Orestes, had escaped destruction.

Great rents gaped where once girders had welded together sturdy permalloy sheets, purposeless shards lay strewn about, even the hammocks had been wrenched from their strong moorings, but he and his companions still lived!

Even as Tim fought to loose the straps that circled him, Captain Lane groaned, stirred, opened his eyes. Dully, then with wakening recollection. And his first word—

"Dorothy?"

"Safe," said Mallory. "She's safe. We're all safe. I don't know how. We must bear charmed lives." He bent over the girl, loosened her straps, chafed her wrists gently. Her eyes opened, and the image of that last moment of panic was still mirrored in their depths. "Tim!" she cried. "Are we—Where's Daddy?"

"Easy, sugar!" soothed Tim. "He's here. It's all over. We pulled through. It was a miracle."

He said it gratefully. But Captain Lane corrected him. The safety of his daughter assured, the old spacedog's next thought had been for his ship. He had walked forward, studied the crumpled ruin of the control-room. Now he said, "Not a miracle, Mallory. A sacrifice. It was Carter. He didn't bail out with the others. He must have stayed on in the control-room, fighting that jammed Dixie-rod. It must have come clean at the last moment, slowing the ship, or we wouldn't be here. But it was too late, then, for him to get away—"

His voice was sad, but there was a sort of pride in it, too. Dorothy began to cry softly. Captain Lane's hand came to his forehead in brief, farewell salute to a gallant man. Then he rejoined the others. "It was the first time," he said, "he ever disobeyed my orders."

Tim said nothing. There was nothing he could say. But for the first time he realized why Captain Lane, why all spacemen, felt as they did about their calling. Because the men who wore space-blues were of this breed.

For a long moment there was silence. Then the old man stirred brusquely.

"Well, we'd better get going."

"Going?" Tim stared about him. It was a far from reassuring scene that met his eyes. They had landed in the midst of wild and desolate country, on a plateau midway between sprawling marshlands below and craggy, cloud-created hills above. The shock of the crash must have stunned into silence all wild-life temporarily, for upon awakening, Tim had been dimly conscious of a vast, reverberant quietude.

But now the small, secret things were creeping back to gaze on the smoking monster that had died in their midst; small squeals and snarls and chirrupings bespoke an infinitude of watchers. The hour was just before dawn; the eastward horizon was tinged with pearl. "Going?" Tim repeated. "But where are we?"

Captain Jonathan looked at him somberly. "In the Badlands," he said. "And the term is not a loose one; they are bad lands, Mallory." He pointed the hour hand of his wrist-watch at the pale mist of rising sunlight. "I don't know exactly where we are, or how far from civilization, but it's far enough."

Tim said determinedly, "Then we'd better pack up, eh? Hit the trail?"

The skipper laughed scornfully. "What trail? We'd be committing suicide by heading into those marshes, those hills, or those jungles. Our only chance of survival is to stay close to the Orestes. Five of the sailors bailed out, you'll remember. In safety-sleds. We've got to hope one or more of them will reach Venus City, start a rescue party out after us."

"But you said 'get going'?"

"To work, I meant. We're going to need protection from the sun." Again Captain Lane glanced at the sky, this time a little anxiously. "I know this country. After that sun gets up, it will be a bake-oven. A seething cauldron of heat. Damp, muggy heat. Steam from the marshes below, the raw, blinding heat blazing down from the rocks above. This is Venus, Mallory—" He laughed shortly; but there was no mirth in his laughter. "This isn't an air-conditioned home on Earth. Come along!"

Silently, Tim followed him. They picked their way through the tangled wreckage of the Orestes, stopping from time to time to salvage such bits of equipment as Lane felt might be of use. Flashlights, side-arms, vacuteens of clear, cold water, packets of emergency rations. Through chamber after shattered chamber they moved, Captain Lane leading the way. Tim and Dorothy following mutely behind. Everywhere it was the same. Broken walls, bent and twisted girders, great rents in what had once been a sturdy spacecraft.

And finally Lane gave up.

"It's no use," he said. "There's no protection in this battered hulk. Shading ourselves in one of these open cells would be like taking refuge in a broiler."

"Then what can we do, Daddy?"

"There's only one thing to do. Break out bulgers. They're thermostatically controlled. We'll keep cooler in space-suits than anything else. Mallory, you remember where they were?"

"Yes, sir!" Tim went after the space-suits, grateful for a chance to contribute in some way to their common good. The storeroom in which the bulgers had been locked was no longer burglar-proof; one wall had been sheared away in the crash as if cleft with a gigantic ax. He clambered into the compartment, broke out three bulgers, gathered up spare oxytainers for each of them.

He had just finished lugging the equipment out of the storeroom, sweating from the exertion of lifting three heavy space-suits beneath a sun which was now glowing brazenly in an ochre, misted sky, when a sharp cry startled him.

"Daddy! Behind you!" It was Dorothy who screamed the warning. And then, "Tim! Tim!"

"Coming!" roared Mallory. He was scarcely conscious of the weight of the bulgers now. In a flash he was plunging toward the source of the cry, tugging at the needle-gun in his belt. But before he had taken a dozen steps—

"Never mind, Mallory!" roared Captain Lane. "Stay where you are! Back, you filthy—!" There came the sharp, characteristic hiss of a flashing needle-gun, the plowp! of some unguessable, fleshy thing exploding into atoms. "Stay where you are! We'll come to you. Quick, Dorothy!"

Then their footsteps pounding toward him, Dorothy rounding a bend of the ship, white-faced and flying, Captain Lane on her heels, covering their retreat with his gun. As Mallory sprang to join them Lane flashed him a swift glance and tossed curt words of explanation.

"Proto-balls! Giant, filthy amoebae. Pure proteid matter. Aaah! Scorched that one! Damned needle-guns won't stop 'em, though. Just slows 'em down. Only thing'll kill 'em is an acid-spray. We've got to get out of here!"

"But where, Daddy?"

"Got those bulgers, Mallory? Climb into 'em. And hurry. Saw caves in the mountainside up there. They won't enter caves. Need sunlight. Look out!"

Again that sharp, explosive hiss. Mallory leaped back, feeling the brief, furtive brush of something foreign across the toe of his boot. The attacking proto-balls were of all sizes; they ranged from huge, oily-glistening, foul-odored spheres to tiny globules the size of a baseball. One of the latter size had rolled swiftly toward him; for a second, before Captain Lane's gun splashed flame upon it, it had come in contact with Mallory's foot. Where it had touched was now a patch of crumbling gray that had been leather!

"Eat anything!" rasped Lane. "Didn't touch you, eh, Mallory? Good. Start backing away. And get into the bulgers. Move!"

Mallory climbed swiftly into his space-suit. Its weight disappeared as he touched the grav control button; the heat which had begun to oppress him fled, too, when he closed the face-port. He touched Lane's shoulder, thrust the remaining bulger at him.

"I'll hold them while you get into it!"

And he did. It was an unequal battle, though. The proto-balls were the next thing to imperishable. The needle-gun could not destroy them, it only slowed them down. An occasional perfect bull's-eye shot, striking a vulnerable spot, would burst a proto-ball into a thousand pieces—but when that happened, each of the pieces, amoeba-like, curled instantly into a tiny daughter proto-ball and surged forward again.

Yet there must have been some elementary nervous-system in these creatures, for while it could not kill them, still they seemed to fear the flaming ray of the needle-gun. And it was to this fear that the trio of Earthlings owed their existence during those next hectic minutes while they stumbled, ever backward and upward, giving ground steadily, toward the cave-mouth Captain Lane had pointed out on the hillside.

Tim did not even know the cave was near. Shoulder to shoulder with the old space-captain, he maintained a rear-guard defense against the proto-balls, gun flaming without cessation, his eyes aching from the strain of constant watchfulness against an unexpected flank attack. And then—

And then, suddenly, incredibly, a shadow fell under his stumbling feet; at that line of division between glowing sun and somber shade the proto-balls stopped, quivering and oozing viscous droplets of slime, hesitated, and turned away.

Lane's roar was gleeful. "Good work, young fellow! We made it!"

They were safe in the black harbor of the cave.

When he turned to stare into the depths beyond him, at first he could see nothing but a great orange ball, which was his photo-image of the dazzling sunlight whence they had fled. Then tortured nerves surrendered to the soothing dark and he could see that they stood at the mouth of not a cave but a great, many-corridored cavern that stretched—for all Mallory could tell—clear down into the murky bowels of Venus.

Jonathan Lane was loudly exuberant.

"This is fine!" he declared. "We owe those grease-balls a vote of thanks. This is an ideal refuge. Shady and cool and safe—and look! We can even see the ship from the heights, here! If anyone—I mean, when they come to rescue us, we can signal them."

Mallory hoped the slip had passed unnoticed by Dorothy. "If anyone—" the skipper had started to say. Which meant that he, too, had misgivings as to the likelihood of rescue. But that was a question Mallory would not press. He hurdled the awkward moment with a swift response.

"We'll have to have something to signal with, sir. Our bulger audios won't operate that far, will they? We'll have to build a fire, or at least have one ready to be kindled when they arrive."

"Right," agreed the skipper. "But we can't gather wood until those protos have gone away. We'll take care of that later. Meanwhile—" He glanced into the jetty depths beyond them. "It will be some hours before we can expect to get relief. Time to waste. Why not amuse ourselves by exploring this cave?"

"Explo—" began Tim. It was a childish idea. One so ridiculous, in fact, that it was on the tip of Mallory's tongue to make caustic rejoinder to Lane's suggestion. But even as the comment trembled on his lips, his eyes met those of the captain—and in Lane's shrewd, pleading glance, Tim found a reason and an answer for this subterfuge.

Lane feared that very thing which he, himself, had dreaded. This cave might be their refuge for a long, long time!

There might be no rescue party. If so, and since a trek across the Badlands was suicidal, their only chance for ultimate salvation was to find a place where they could live. This cave was such a place. If it had water, and if it were undenizened by wild beasts; if in it, or near it, they could find food....

He hoped his voice was not too suspiciously hearty.

"Great idea!" he agreed. "Splendid. It should be a lot of fun. What do you say, Dorothy?"

Dorothy looked from her lover to her father, back to her lover again. And her voice was grave and fearless.

"I say," she said quietly, "you are the two finest men who ever lived. But you're not fooling me for a moment. I know very well why we must explore this cave. And I say, let's start!" There came swift lightness and heart-warming humor to her tone. "After all, if a gal has to keep house in a place like this, she ought to know how many rooms it has!"

Tim looked at her long and gravely. And then,

"You," he said, "are swell. Once I called you wonderful. I didn't really know—then."

"Wonderful?" snorted Captain Lane. "Of course she is! She's my daughter, isn't she? Well, come along!"

Grinning, Tim fell in behind him. And into Stygian darkness, preceded by a yellow circle from the flashlight of the Orestes' skipper, moved the marooned trio.

The main cave opened out as they picked their path forward; the walls pressed back, the ceiling lofted, until they were standing in a huge, arched chamber almost two hundred feet wide and half as high. This amphitheater debouched into a half dozen or more smaller corridors or openings; for a moment Captain Lane stood considering these silently, then he nodded toward that on their extreme left.

"Might as well go at it in orderly fashion. We'll try that one first. No, wait a minute!" He halted Tim, who had pressed obediently toward the corridor-mouth. "Try not to be a groundhog all your life, Mallory! You should know better than to stroll aimlessly around a place like this. A confounded labyrinth, that's what it is! If we got lost down here, we might spend the rest of our natural lives trying to find a way out."

He slipped his needle-gun from his bulger belt, let its scorching ray play for an instant on the rocky floor of the cavern. Hot rock bubbled, and a fresh, new groove shone sharply in the shape of an arrow.

"Every time we make a turn we'll do this. Then we can retrace our steps." Lane smiled sarcastically. "But a hot-and-cold engineer wouldn't think of a thing like that, I suppose?"

Tim made no reply. But he reproached himself secretly for not having considered this necessity; it did not make him feel much better that Dorothy, standing beside him, pressed his arm in mute encouragement.

The corridor was a short one, opening into another cavern like that which they had just quitted. Similar, but not quite the same. For as Lane played his light about the walls of this inner, deeper, chamber, all three adventurers gasped with the impact of sudden, breathtaking beauty. The ebon walls, warmed by the light, flashed into a glittering, scintilliscent miracle of loveliness; a galaxy of twinkling stars seemed to appear from nowhere and hang in dark space burning and gleaming.

"It—it's magnificent!" breathed the girl. "What is it, Daddy? Jewels? It looks like the fabulous caves of Ali Baba."

It was Tim who supplied the answer. "They're not jewels. Just nitre crystals protruding through a coating of black oxide of manganese. I've seen the same thing on Earth—in the Mammoth Cave of Kentucky."

And they moved on. Deeper and yet deeper into the Lethean depths, pausing from time to time to char a signpost for their retreat. Miracles without wonder they saw. Domes huge enough to house a spaceship, stalactites lowering like great, rough fangs from ceilings lost in dizzy heights, twin growths springing, oftimes without apparent reason, from the cavern floor—stalactites formed by centuries of slow lime dripping from the roof. And gigantic columns, hoariest monsters of all, columns of strange, iridescent beauty.

Once they passed a pit so deep, so dark, that even the skipper's probing beam could not penetrate its majestic depths. From somewhere far below came the whispering surge of churned water; in the light of the flash there seemed to hover above the rim of this chasm a faint, white, wraithly film. Lane frowned, unscrewed his face-port for an instant, sniffed, and hastily ducked back into the bulger.

"Ammonia," he said. "I thought as much. Keep your bulger-ports closed. Venus caves aren't Earth caves. Queer things here. No telling what we'll bump into."

He didn't mention the all-too-obvious fact that so far they had not "bumped into" that thing which they sought. A fuel supply, a water supply, signs of an underground grotto wherein might be found food. Nor had their winding way at any time moved them toward the surface, toward a possible second exit from the caverns. Their movement was ever down, deeper into the bowels of this weird, faery wonderland.

Once, for a heart-stopping moment, they thought they had found their desire. Rounding a bend, they came upon a cavern alive with color; towering vines and trees laden with great clusters of grapes; bushes aflower with myriads of gorgeous buds. Dorothy sprang forward with a cry of joy—but when she touched one of the mock roses it shattered to fine, white, powdery snow; upon investigation the trees, the vines and "grapes" turned out to be of the same, perishable nature.

And Tim remembered their name. "Oulopholites," he said. "Sulphate of magnesia and gypsum. Mother Nature does repeat herself, you see. She uses the same forms, but these are lifeless mimicry." And he looked at his watch. "Guess we'd better turn back, eh, skipper? We've been two hours on the prowl, and there doesn't seem to be anything in this direction. Shall we go back and try another corridor?"

Lane nodded slowly.

"I suppose so. But—Oh, while we're this far, we might as well peek into that next cavern. Won't take but a minute. And if there's nothing there—"

The words died on his lips. As he spoke them, they had moved through a short archway; the yellow circle of his flashlight had swung about a cavern larger than any in which they had yet stood. The floor of this cavern sloped sharply downward, narrowing into a funnel. And at the end of that funnel....

"Great gods of space!" whispered Captain Lane, awestruck. "Am I crazy? Do you see what I see?"

For that upon which his lightbeam had ended, the incredible structure from which its glow was now reflecting in shimmering clarity, was—a massive door of bronze! Golden in sheen, strong and secure, obviously the work of intelligent craftsmen, it met their wondering stares with bland imperturbability.

And Tim gave a great shout.

"A door! Venusians! We're all right now. Food and rest ... they'll tell us how to get back to civilization...."

And then—

"Quiet!" rasped Captain Lane. His flashlight beam faded abruptly, darkness closed in about them like a shroud. But only for an instant. Because a new effulgence lit the scene. The massive door was slowly swinging open—and from its widening groove came a pallid, greenish glow. Like some monstrous, hungry mouth the door opened wider and yet wider. Dim shapes were shadows behind it, vague at first, dark and sinister....

And then, out of the ghoulish semi-gloom, suddenly two figures stood limned in stark relief. But they were not the figures of Earthmen, neither were they fat, friendly shapes of Venusians. They were tall, lean creatures, thin-faced and hungry-fanged, garbed with what appeared to be huge mantles covering them from their shoulder-blades to the tips of their long, prehensile fingers!

Two wobbling, awkward steps they took from the now completely opened door; for an instant Tim heard the shrill, piping chatter of their speech—then their "mantles" spread and became huge, jointed wings on which they soared straight across the cavern toward the spellbound trio!

Captain Lane's cry was thick with horror.

"Good God, Mallory! Shoot, and shoot quick! We've found the gates of hell. They're the bat-men—the Vampires of Venus!"

Even as he spoke, he was tugging his own needle-gun from its holster; now its fiery beam lanced squarely at the foremost of the two attackers. Nor was Tim Mallory slow in heeding. His weapon was out in one swift movement; its beam slashed a hole in the gloom as it sought one of the silently winging creatures above.

But they might as well have taken aim at a will-o'-the-wisp. The dim glow from beyond the open door illumined only a portion of the cavern; the heights above were a well of jet, against which the crepuscular creatures were all but invisible. Again and again the two heat-beams stabbed black shadows, once Tim thought he heard a brief, whimpering cry, but no winged creature, charred in death, hurtled from the eyrie point of vantage. Only the sound of great wings beating persisted—and once an ebon shape flung itself from an ebon shadow to rake sharp claws gratingly across Tim's bulger helmet. It had glided away again, mockingly, before he could spin to flame a shot after it.

Then Lane's free arm was thrusting at him. Lane's voice was sharp, incisive.

"Out of here! Dorothy first! Maybe there are just two of these devils—Ooow! Damn your rotten hide!"

He had turned to speak over his shoulder. In that moment of inattention, one of the bat-men had rocketed down upon him, slashed viciously at his gun-arm with clawed hands. Metal clattered on rock; Captain Lane went swiftly after the lost gun, groping for it blindly, down on his knees.

Tim had taken a backward step; now he moved forward again to cover the frenzied fumbling of the older man. His eyes were suddenly dazzled as Lane, desperate, used his flash to search for the weapon. And the skipper groaned.

"It's gone! It fell down that fissure! Mallory—quick! Do you have another gun? They're closing in—"

Beads of cold sweat had suddenly sprung out on Tim Mallory's forehead. Not only did he not have another gun—but the one he now held was about to become useless! A dim shape wheeled above him; he pressed the trigger, but no red flame leaped from the muzzle. Just a spluttering, ochre ray that simmered into nothingness a few feet above his head!

The gun's charge was practically exhausted. Battle with the proto-balls ... the constant drainage of raying their route-turns ... these had done it! There were fresh capsules in his ammunition kit, but in the length of time required to recharge the gun....

"A minute!" he cried. "Fight 'em off a minute! I have to—"

And he reached for a new capsule. But the skipper, misunderstanding, impatient, turned peril into disaster with his next, impetuous move.

"Don't stand there like an idiot, you Earthlubber!" he howled. "Here—give that to me!"

And he jerked the useless weapon from Tim's hand!

For a stark instant, Tim was wrenched in a vise of indecision. To fight the winged demons without a weapon was madness. Wisdom lay in hurrying back to the ship, equipping themselves with new guns. But—but Lane had said these bat-men were vampires. The Vampires of Venus, he had said. And Tim had heard stories ... the word "vampire" meant the same in any language, on any planet.

But there was Dorothy to consider, too. He groaned aloud. His instinct bade him plunge forward, weaponless or not; common sense advised the other course.

And then, in a split-second, the decision became no longer his to make. For as if the victory of the first two bat-men had determined the action of the entire clan, out of the bronze gateway flooded a veritable host of the sickening winged creatures!

Then a battering-ram smashed him crushingly and he choked, gasped, felt the weakness of oblivion well over him like a turgid, engulfing cloud. He was conscious of raking talons that gripped his armpits, of sudden, swift and dizzy flight ... of a vast, aching chaos that rocked with hungry, inhuman mirth.

Captain Lane's voice was an aeon away, but it came closer. It said, "—be all right now. You must have been in a hell of a fight, boy!"

And Dorothy was beside him, too. There were tears in her eyes, but she shook them away and tried to smile as Tim pushed himself up on one elbow. Tim's head was one big ache, and his body was bruised and sore from the buffeting of the bat-men's hard wings. He looked about him dazedly.

"Wh-here are we?"

The room was a low-ceilinged, square one. It had but one door, a bronze one similar in design, but smaller, than the gateway that had led to the city of the Vampires. Elsewhere the walls were hewn from solid rock.

"Where are we?" he repeated. He started to unscrew his face port, but the skipper stayed his hand.

"Don't, Mallory! We tried that. It's impossible. The air's so ammoniated it would kill you. From that."

He pointed to a trough-like depression in the room. A curious arrangement. Probably for purposes of sanitation. Liquid ammonia, or something akin, entered the trough from a gushing tube set low in one wall, transversed the room, and exited through a second circular duct. These were the only openings in the chamber, save for—Tim glanced up, noticed several round holes. He studied these curiously. Lane answered his unspoken query.

"Yes, that's right. Ventilation. These devils may be inhuman in form but they're clever. They've built this underground city, equipped it with heat, light, ventilated it to maintain circulation—"

There was something wrong there. Tim frowned.

"Ventilation? Yet you say that stream is ammoniated enough to kill a man. Then how do they live?"

"They're not men," replied Lane bitterly. "They're vampires. Heaven knows how they can breathe this atmosphere, but they can. The ingenious, murdering..."

He didn't complete the sentence. For at that instant there came the scrape of movement outside their dungeon door. The door swung open. A bat-man entered. His hooked claw signalled them to come forth. Tim glanced at the older man. Lane shrugged resignedly.

"There's nothing else to do. Maybe we can strike a bargain with them. Our freedom for something they want."

But there was no hope in his voice. Tim threw an arm about Dorothy's shoulders. They followed their guide out of the room. There a cordon of other bat-creatures circled them, and Tim, for the first time, got an opportunity to see his captors at close range.

They weren't much to look at. They were such stuff as nightmares are made of. Tall, angular, covered from head to toe with a stiff, glossy pelt of fur. Their faces were lean and hard and predatory; their teeth sharp and protruding. Their wings were definitely chiropteric; the wing-membranes spanned from their shoulders to their claws, falling loosely away when not in use, and were anchored to stiff, horny knobs at clavicle and heel.

They walked now, guarding their captives, but it was apparent that flight was their usual method of locomotion. Anything else would be awkward, for their knees bent backward as did the knees of their diminutive Earthly prototype.

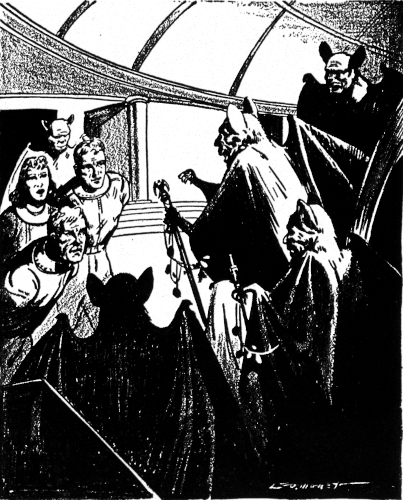

They turned, at last, into a huge chamber. And before them, perched obscenely on a platform elaborately laid with jewels and tapestries, was the overlord of the Harpies.

No man, by the wildest stretch of the imagination, could have considered any of the vampires attractive. But of all they had seen, this monster was the most repugnant. It was not only that his frame was tauter, skinnier, than that of his fellows; it was not that his furry body was raw and chafed, as if from ancient, unhealed sores; it was not only that his pendulous nose-leaf perpetually snuffled, pulsed, above a red-lipped, vicious mouth. It was the unclean aura of evil about him that made Tim feel dirty. As though by merely looking on this thing he had profaned himself in some strange, inexplicable fashion.

Dorothy felt it, too. She choked once, turned her face away. And Captain Lane growled a disgusted curse.

"Lord, what a filthy beast! Mallory, I wouldn't mind dying if I could get one shot at that pot-bellied horror first!"

He did not expect—none of them could have expected—that which happened then. There came a high, simpering parody of laughter from the thing on the dais before them. And the words in their own tongue—

"But you cannot, Man! For here I am the Master!"

Lane's jaw dropped; his eyes widened. Tim Mallory felt the small hairs at the nape of his neck tighten coldly. The bat-thing could speak! Was speaking again, its cruel little mouth pulled into a grimace remotely resembling a grin.

"You are surprised that I speak your language? Ah, that is amusing. But you are just the first of many who will soon discover how foolish it was to underestimate the intellect of our ancient race.

"With fire and flame you forced us to the caverns, Man-thing. But we are old and wise. We built our cities here, warmed them against the dreadful damp and cold. Soon we shall burst forth in all our might. And when we do—"

He stopped abruptly; the tensing of his claws told the rest more eloquently than words. He rapped a command to one of the guards.

"Take off their garments! I would see what prizes have stumbled into our refuge!"

Obediently, the bat-creature shambled forward; his talons fumbled at Captain Lane's face-port. Tim cried out, "No! Don't let him! The atmosphere—"

The vampire overlord grinned at him cunningly.

"Fear not, Earthman. The air in this chamber will not harm you. We have other plans—" His wet, red tongue licked his lips.

Then Lane's headpiece was removed, and his bulger was stripped from him. A dazed expression swept across his forehead. He said, "Mallory—it—it's hot in here! And the air is breatheable!"

But by that time, Tim, too, had been removed of his space-suit; he, too, had felt the sultry, oppressive heat of the cavern. It was incredible but true. The vampires had found a way to make their underground city warm as the surface from which men had hunted them. That then—it came to Tim with sudden, startling clarity—that was why—

The overlord was speaking again. His tone was one of gratification.

"The men will do. We shall feast well tonight—very well! The woman—" He gazed at Dorothy speculatively. "I wonder?" he mused in a half whisper. "I wonder if there is not a better way of undermining Earthmen than just crushing them? A new race to people Venus? A race combining our ancient, noble blood and that of these pale creatures?" His eyes fastened on Dorothy's suddenly flaming loveliness. "That is a matter I must consider.

"That will do!" He motioned to his followers even as Tim, white of lip and riotous with rage, took a forward step. "Allow them to don their clumsy air-suits again; take them back to their dungeon. We shall bring them forth again when the time is ripe."

Strong claws clutched Mallory, staying him. Short minutes later, surrounded by their guards, they were once more on their way to the nether prison.

It was a grim-faced Captain Lane who paced the floor of their dungeon. There was anger in his eyes, and outrage, too. But beneath those surface emotions was a deeper one—fear! The dreadful, haunting fear of a powerless man, caught in a trap beyond his utmost devising.

"If there were only something we could do!" he raged savagely. "But we're weaponless—helpless—we can't even die fighting, like strong men. I'd rather we had all died in the Orestes than that this should happen. You and I, Mallory, a feast for such foul things. Dorothy—"

He stopped, shaken, sickened. Dorothy's face was pale, but her voice was even.

"There is one thing he overlooked, Daddy. We still have the privilege of dying cleanly. Together. We can take off our suits. Here. Before they come for us."

Lane nodded. He knew what death by asphyxiation meant; he had seen men die in Earth's lethal chambers. But anything, even that, was better than meek surrender to the overlord's mad, lustful plan.

"Yes, Dorothy. That is the only way left to us." He thought for a moment. "There is no use delaying. But before we—we go, there is one thing I must say—" And he looked at his daughter and her lover in turn. "I was wrong in forbidding your marriage. You're a man, Mallory. It's too bad I had to learn that under such circumstances. But I want you to know—at the end—that if things had turned out differently, I—I'd change my mind."

Tim said quietly, "Thank you, sir." But his thoughts were only half upon the older man's admission. There was a tiny something scratching at the back of his mind. Something that had occurred to him, dimly, in the hot chamber above. He couldn't quite place his finger on it, but—

"I still find it in me to wish," said Captain Lane, "that you had been a spaceman. But there's no use talking about that now. What might have been is past. There remains only time to acknowledge past faults, and then—and then—"

He faltered. And Dorothy took up the weighty burden of speech.

"Shall we ... do it now?"

Her hands lifted to the pane of her helmet. For an instant they hesitated, then began to turn. And then—

"Stop!" cried Tim. He struck her hands away, spun swiftly to the older man. "Don't do it, Skipper! I've got it! Got it at last!"

Lane stared at him dazedly. "Wh-what do you mean?"

Tim's sudden laughter was almost hysterically triumphant. "I mean that this is one time a 'groundhog engineer' knows more than a spaceman. There's no time to explain now, but quick!—you have some gun-capsules, haven't you?"

"Y-yes, but—"

"Give them to me! All you have. And hurry!"

As he spoke, he was emptying his own capacious ammunition pouch. Capsule after capsule poured from it, until he had an overflowing double handful. With frenzied haste he broke the safety-tip off the first, tossed the cartridge into the stream that ran through their prison. As it struck, it hissed faintly; bubbles began to rise from the fluid, and a thin, steamy film of vapor rose whitely.

"Do that to all of them. Toss them in there! I'm right! I know I am. I have to be!"

Bewilderedly, Captain Lane and Dorothy began doing as he ordered. A dozen, a score, twoscore of the heat-gun cartridges were untipped, thrown into the coursing stream. The white film became a cloud, a fog, a thick, dense blanket about them, through which they could barely see each other. And still Tim's voice cried, "More! Faster! All of them!"

Then the last capsule had been tossed into the fluid, and their only contact with each other was by speech and the sense of touch. They were engulfed in rolling billows of white; vapor that frosted their view-panes, screened the world from view.

For half an hour they stood there waiting, turn with a thousand mingled doubts. Until, at last—

"I can't stand it any longer, Tim!" cried Dorothy. "What is it? What do we do? What is this wild plan?"

The vapor had thinned a trifle. And through gray mists, she saw a form loom before her. It was Tim's shape, and his hand stretched out to her. His voice was tense.

"Now—" he said. "Now we walk from our prison!"

And he flung open the door.

"Careful!" cried Captain Lane. "The guards, son! 'Ware the Harpy guards!"

But no guards sprang forward to bar their passage. There were guards, a dozen of them. But not a single one of them moved.

And Dorothy, wiping a sudden veil of hoar-frost from her view-pane, saw them and gasped.

"Dead!" she cried. "Tim—they're all dead!"

Tim shook his head.

"Not dead, darling. Just—sleeping! And now let's hurry. Before they waken again!"

When they had reached the uppermost corridor of the caverns, they paused for a moment's rest. It was then that Captain Lane found time for the question that had plagued him.

"You were right, Tim. They were sleeping. I could see that overlord's nose-leaf quivering with slow breath just before I shot him. But—but what caused it? Anesthetic? I don't understand."

"No," grinned Tim, "it was not an anesthetic. It was a simple matter of remembering a biological trait of bats, and applying a little technical knowledge. The knowledge—" He could not resist the dig. "The special knowledge of what you called a 'hot-and-cold' expert. Refrigeration!

"Bats are hibernating creatures. And hibernation is not merely a matter of custom, tradition, desire to sleep—it is a physical reflex which cannot be avoided when the conditions are made suitable.

"Bats, like many other hibernating mammals, are automatically forced into slumber when the temperature drops below 46°F. Knowing this, and realizing that was the reason the Harpies—bat-like in form and habit—kept their underground chambers superheated I applied an elemental principle of refrigeration to cool their city below that point!"

Dorothy said, "The—the ammonia—?"

"Exactly. The set-up was perfect. Our apparatus was, perforce, crude, but we had all the elements of a refrigerating unit. Ammoniated water, running in a constant stream, capsules of condensed and concentrated heat from our needle-guns—a small room which was connected, by ventilating ducts, with the rest of the underground city.

"The principle of the absorption process depends on the fact that vapors of low boiling point are readily absorbed in water and can be separated again by the application of heat. At 60°F, water will absorb about 760 times its own volume of ammonia vapor, and this produces evaporation, which, in turn, gives off vapor at a low temperature, thereby becoming a refrigerator abstracting heat from any surrounding body. In this case—the rooms above!

"It—" Tim grinned. "It's as simple as that!"

Captain Lane groaned.

"Simple!" he echoed weakly. "The man says 'simple'! I don't understand a word of it, but—it worked, son! And that's the pay-off."

"No, sir," said Tim promptly.

"What? What's that?"

"The pay-off," persisted Tim, "comes later. When we get back to civilization. You said something about removing your objections to our marriage, remember?"

Captain Jonathan growled and stood up. "Confound it, do you think of everything? Well—all right, then. I'm a man of my word. But when we get back to civilization may be a long time yet."

"I can wait," grinned Tim. "But I've got a feeling I won't have to wait long. Maybe I'm psychic all of a sudden. I don't know. But somehow I've got a hunch that when we get to the cave-mouth, we're going to find a rescue party waiting for us up there. I just feel that way."

"Humph!" snorted Lane. "You're a dreamer, lad! A blasted, wishful dreamer!"

But it was a good dream. For the hunch was right.