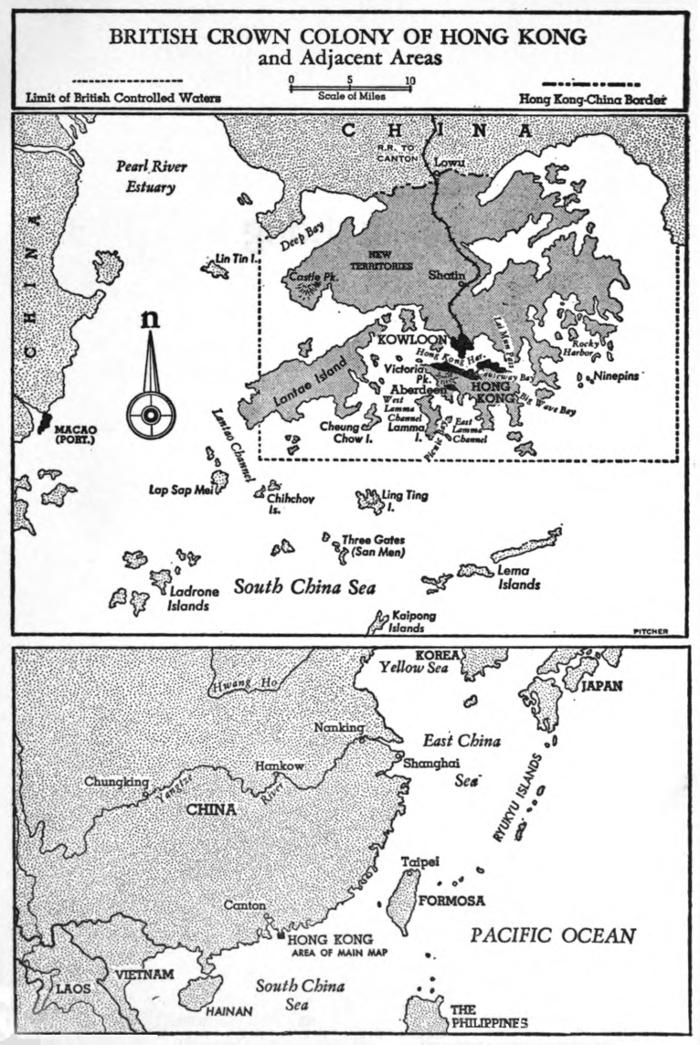

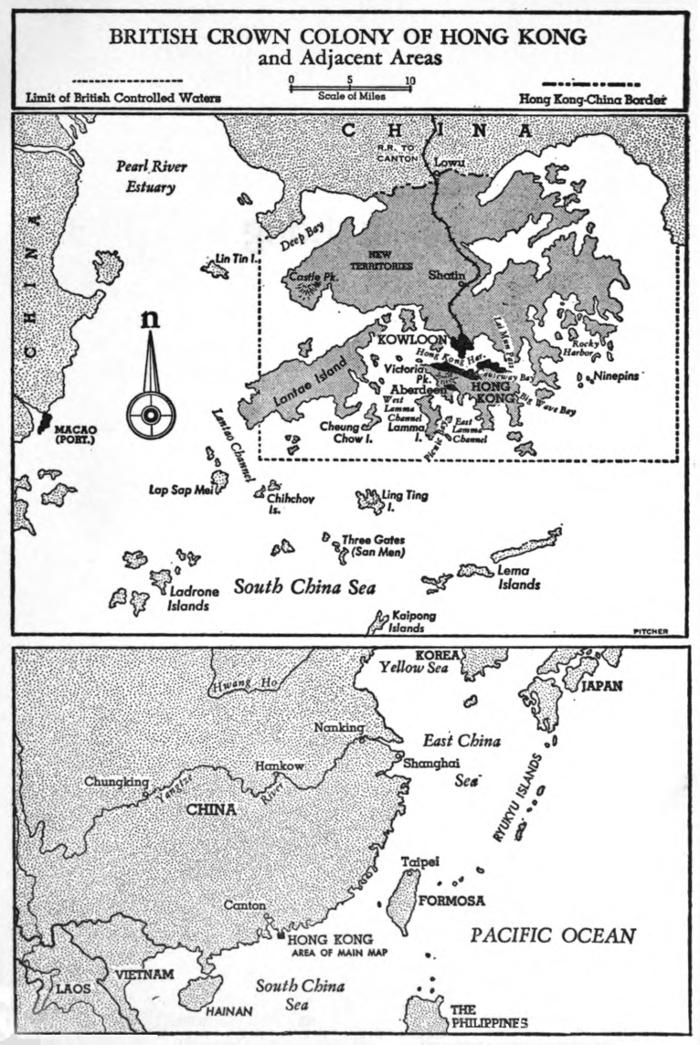

BRITISH CROWN COLONY OF HONG KONG

and Adjacent Areas

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Hong Kong

Author: Gene Gleason

Release Date: May 22, 2020 [eBook #62191]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HONG KONG***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through HathiTrust Digital Library. See https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015002199274 |

Hong Kong

Hong Kong

Gene Gleason

The John Day Company, New York

© 1963 by Gene Gleason

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission. Published by The John Day Company, 62 West 45th Street, New York 36, N.Y., and simultaneously in Canada by Longmans Canada Limited, Toronto.

Library of Congress Catalogue

Card Number: 63-7957

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To all who helped—

particularly, Pat

| Introduction | 11 | |

| 1. | Up from British Barbarism | 15 |

| 2. | An Avalanche from the North | 47 |

| 3. | Conflict and Coexistence with Two Chinas | 85 |

| 4. | Industrial Growth and Growing Pains | 113 |

| 5. | High Land, Low Water | 155 |

| 6. | A New Day for Farms and Fisheries | 175 |

| 7. | Crime, Power and Corruption | 201 |

| 8. | Two Worlds in One House | 227 |

| 9. | Rambling around the Colony | 259 |

| 10. | Shopping before Dinner | 289 |

| Index | 309 |

Sixteen pages of illustrations will be found following page 160.

BRITISH CROWN COLONY OF HONG KONG

and Adjacent Areas

Hong Kong is a high point on the skyline of the Free World. As a free port operating on a free-world basis, it is too valuable to lose.

—Sir Robert Brown Black, Governor of the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong, 1962

Except for Portugal’s tiny overseas province of Macao, Hong Kong is the last Western outpost on the mainland of China. It is the Berlin of East Asia, poised in perilous balance between two ideologies and two civilizations.

The government and people of Hong Kong have performed a matter-of-fact miracle by saving the lives of more than a million refugees from Red China. Without appealing for foreign aid or emergency subsidies from the home country, the colony’s rulers have provided jobs, homes and freedom for the destitute. Private charitable organizations overseas and outright gifts from the governments of Great Britain and the United States have achieved miracles on their own in[12] feeding, clothing and educating the poor of Hong Kong, but the main burden is too great to be borne by any agency except the full public power of the royal crown colony.

Most of Hong Kong’s people are too poor to afford what an American would consider minimum comforts. They came to Hong Kong with nothing, yet every day they send thousands of food packages back to Red China, hoping to save their relatives from starvation.

These are only the workaday miracles of Hong Kong; the greatest miracle is that it exists at all. It has never had enough of the good things—land, water, health, security or money—but always a surplus of the bad ones—wars, typhoons, epidemics, opium, heroin, crime and corruption.

It is one of the most contradictory and baffling places in the contemporary world—a magnificent port and a teeming slum; a bargain-hunter’s paradise and a nest of swindlers; a place of marginal farmland and superlative farmers, efficient and orderly, sly and corrupt. It has outlived a thousand prophecies of its imminent doom. Its people dwell between the claws of a tiger, fully aware of the spot they’re on, but not at all dismayed.

Tourists and sailors come to Hong Kong by the hundreds of thousands every year, half-expecting to discover inscrutable Orientals, or to be followed down a dark alley by a soft-shod killer with a hatchet in his hand. The Orientals turn out to be the noisiest, most gregarious people the Westerner has ever seen. No one follows him down a pitch-black alley at midnight, unless it’s a stray cat looking for a handout, or a shoeshine boy working late.

The real magic of Hong Kong is that none of it is exactly what you expected. You prowl around for handicraft shops and find them next to an automated textile mill. You’ve been[13] told to keep your eye open for the sprawling settlements of squatter shacks, and you find them slowly being swallowed up by multi-story concrete resettlement estates. You turn on the faucet in your hotel at noon and it issues a dry, asthmatic sigh; you try it again at six and it spits at you like an angry camel, splashing all over your suit.

You look for a historic hill in Kowloon, and there is what’s left of it—a stumpy mound, shaved down by a bulldozer, with the rest of it already dumped into the sea to form the foundation of a new industrial city. You look for the romantic hallmark of Hong Kong, a Chinese junk with bat-wing sails, and it putt-putts past on a Diesel engine without a scrap of canvas on the masts.

You fear for your life as you stand on the crowded sidewalk, plucking up the courage to bull your way through a fantastic tangle of autos, motor-scooters, double-deck trams, rickshaws, massed pedestrians and laborers carting bulky loads on bamboo shoulder-slings, but the white-sleeved patrolman in the traffic pagoda parts the torrent with a gesture like Moses dividing the Red Sea and you cross without a scratch.

A small, slender Chinese beauty in a closely fitted Cheongsam strolls by with a skirt slit to the mid-thighs, and you begin to perceive the reason for the thousands of Caucasian-Chinese intermarriages in the colony. Such unions go so well they hardly merit comment in today’s Hong Kong gossip; a generation ago, they would have overturned a hornet’s nest of angry relatives in both racial groups.

Hong Kong is like the Chinese beauties in their Cheongsams; no matter how often you turn away, your next view will be completely different and equally rewarding.

The common disposition of the English barbarians is ferocious, and what they trust in are the strength of their ships and the effectiveness of their guns.

—Governor Lu K’u of Canton, 1834

In 1841, the British crown colony of Hong Kong attached itself like a small barnacle to the southeast coast of the Celestial Empire. The single offshore island that constituted the whole of the original colony was a spiny ridge of half-drowned mountains forming the seaward rampart of a deep-water harbor. Before the British came, it had no geographic identity. They gave it the Chinese name “Hong Kong,” usually translated as “fragrant harbor,” which distinguished the one appealing feature of its forbidding terrain.

Sparsely inhabited from primitive times, Hong Kong, the more than two hundred rocky islands scattered outside its harbor, and the barren seacoast opposite them lay far out in the[16] boondocks of China. Its innumerable, deeply indented coves and mountain-ringed harbors made it a favorite lurking place for coastal pirates.

For centuries, fleets of pirate junks had apportioned their rapacity between pouncing on coastwise ships and pillaging isolated farms and fishing settlements. The Manchu emperors, lacking the unified navy necessary to sink these cut-throats, attempted to bolster the thin defenses along the pirate-infested coast of Kwangtung Province by offering tax-free land to any of their subjects who would settle there. Even so, there was no wild scramble to accept the gift.

Less troublesome than pirates but hardly more welcome to the rulers of China were the European traders who had been plying the Chinese coast since the beginning of the sixteenth century. In the middle of that century, Portuguese merchant-sailors overcame part of this hostility by employing their well-armed ships to help the Chinese emperor crush a pirate fleet. They were rewarded with imperial permission to establish a small trading outpost at Macao, forty miles west of Hong Kong Island.

Traders from Spain, Holland, England, France and America soon began to operate out of Macao, and the British East India Co. opened a trade base at Canton in 1681 to supply a lively English market with Chinese tea and silk. Canton, the only Chinese port open to world trade, stood due north of Macao and ninety-one miles northwest of the future colony at Hong Kong.

Throughout a century and a half of dealings at Canton, European traders enjoyed the same degree of liberty: they were all free to pay whatever prices or imposts the Chinese Hong merchants and customs officials chose to demand. The Chinese wanted neither foreign goods nor foreign traders,[17] but if the latter persisted in buying and selling at Canton, they were expected to submit to strict Chinese regulations or get out.

There were rules forbidding any foreigner to live in Canton except during the six-month trading season, rules denying foreign women the right to enter the city, rules against possessing firearms and an absolute ban against bringing foreign warships past the Boca Tigris (Tiger’s Mouth), the fortified strait on the Canton River estuary leading to the city.

In practice, the rules were a kind of game; few were consistently enforced unless the Western traders raised a howl over Chinese customs duties or bumptiously insisted on dealing directly with the officials of the Celestial Empire instead of its merchants. Then the reins were yanked up tight, and the commercial interlopers had to obey every restriction to the letter.

Foreigners at Canton remained in a weak bargaining position until a few European traders, particularly the English, discovered one product that the Chinese passionately desired. It was compact, easy to ship, extremely valuable, and it brought full payment in hard cash upon delivery. It could be brought from British India in prodigious quantities, and because it contained great value in a small package, it could slip through Chinese customs without the disagreeable formality of paying import duties. This was opium—the most convincing Western proof of the validity of the profit motive since the opening of the China trade.

The Chinese appetite for opium became almost insatiable, spreading upward to the Emperor’s official family and draining away most of the foreign exchange gained by exporting tea and silk. The alarmed Emperor issued a denunciation of this “vile dirt of foreign countries” in 1796, and followed it[18] with a long series of edicts and laws intended to stop the opium traffic.

The East India Co., worried by repeated threats of imperial punishment, relinquished its control of the opium trade and dropped the drug from its official list of imports. Private traders with less to lose immediately took up the slack, and after opium was barred from Canton, simply discharged their cargoes of dope into a fleet of hulks anchored off the entrance of the Canton River estuary. From the hulks it was transshipped to the mainland by hundreds of Chinese junks and sampans. Chinese port officials, well-greased with graft, never raised a squeak of protest.

The Emperor himself seethed with rage, vainly condemning the sale of opium as morally indefensible and ruinous to the health and property of his people. Meanwhile, the trade rose from $6,122,100 in 1821 to $15,338,160 in 1832. The British government took a strong official line against the traffic and denied its protection to British traders caught smuggling, but left the enforcement of anti-opium laws in Chinese hands. A joint Sino-British enforcement campaign was out of the question, since the Chinese had not granted diplomatic recognition to the British Empire.

This insuperable obstacle to combined action was the natural child of Chinese xenophobia. When Lord Napier broached the subject of establishing diplomatic relations between Britain and China in 1834, the Emperor’s representatives stilled his overtures with the contemptuous question, “How can the officers of the Celestial Empire hold official correspondence with barbarians?”

The glories of a mercantile civilization made no impression on a people who regarded themselves as the sole heirs of the oldest surviving culture on earth. To the lords of the Manchu[19] empire, English traders were crude, money-grubbing upstarts who had neither the knowledge nor the capacity to appreciate the traditions and philosophy of China. What could these cubs of the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution contribute to a civilization of such time-tested wisdom? They could contribute to its collapse, as the Chinese were to learn when their medieval war-machine collided with the striking power and nineteenth-century technology of the British Navy.

After the East India Co. lost its monopoly on the China trade in 1833, the British government sent its own representatives to settle a fast-growing dispute between English and Chinese merchants. Once again the Chinese snubbed these envoys and emphasized their unwillingness to compromise by appointing a new Imperial Commissioner to suppress the opium trade.

For a time, the British merchants comforted themselves with the delusion that Lin Tse-hsu, the Imperial Commissioner, could be bought off or mollified. He dashed these hopes by blockading the Boca Tigris, surrounding the foreign warehouses at Canton with guards and demanding that all foreign merchants surrender their stock of opium. He further insisted that they sign a pledge to import no more opium or face the death penalty.

Threats and vehement protests by the traders only drove Lin to stiffer counter-measures, and the British were at last forced to surrender more than 20,000 chests of opium worth $6,000,000. Commissioner Lin destroyed the opium immediately. British merchants and their government envoys withdrew from Canton by ship, ultimately anchoring off Hong Kong Island. None of them lived ashore; the island looked too bleak for English habitation, though it had already been considered as a possible offshore port of foreign trade.

With the British out of the opium trade, a legion of freelance[20] desperadoes flocked in to take it over, leaving both the British and Chinese governments shorn of their revenue. Further negotiation between Lin and Captain Charles Elliot, the British Superintendent of Trade in China, reached an impasse when Lin declined to treat Elliot as a diplomat of equal rank and advised him to carry on his negotiations with the Chinese merchants.

Having wasted their time in a profitless exchange of unpleasantries, both sides huffily retired; the Chinese to reinforce their shore batteries and assemble a fleet of twenty-nine war junks and fire rafts, and Captain Elliot to organize a striking force of warships, iron-hulled steamers and troop transports.

The junk fleet and two British men-of-war clashed at Chuenpee, on the Canton River estuary, in the first battle between British and Chinese armed forces. It was a pushover for the British; Chinese naval guns were centuries behind theirs in firepower, and the gun crews on the junks were pitifully inaccurate in comparison with the scientific precision of the British. Within a few minutes the junks had been sunk, dismasted or driven back in panicky disorder. The British on the Hyacinth and Volage suffered almost no damage or casualties.

No formal state of war existed, however, so Captain Elliot broke off the one-sided engagement before the enemy had been annihilated. He pulled back to wait until orders came from Lord Palmerston, British Foreign Secretary, directing him to demand repayment for the $6,000,000 worth of opium handed over to Lin. At the same time, Elliot was told to obtain firm Chinese assurance of future security for traders in China, or the cession of an island off the China coast as a base for foreign trade unhampered by the merchants and officials of the Celestial Empire. Palmerston, maintaining the calm detachment of a statesman 10,000 miles distant from the[21] scene of battle, thought it would be best for Elliot to win these concessions without war.

Elliot, mustering the full strength of his land and sea forces, blockaded the Canton and Yangtze Rivers, occupied several strategic islands and put Palmerston’s demands into the hands of Emperor Tao-kuang. Humiliated by the irresistible advance of the despised foreigners, the Emperor angrily dismissed Commissioner Lin. His replacement, Commissioner Keeshen, began by agreeing to pay the indemnity demanded by Lord Palmerston and to hand over Hong Kong Island, then deliberately dragged his feet to postpone the fulfillment of his promises. Elliot, fed to the teeth with temporizing, ended it by throwing his whole fleet at the Chinese. His naval guns pounded their shore batteries into silence, and he landed marines and sailors to capture the forts guarding Canton.

The Chinese land defenders were as poorly equipped as the sailors of their war junks; when they lighted their ancient matchlocks to fire them, scores of soldiers were burned to death by accidentally igniting the gunpowder spilled on their clothing.

In a naval action at Anson’s Bay, the flat-bottomed iron steamer Nemesis, drawing only six feet of water, surprised a squadron of junks by pushing its way into their shallow-water refuge. A single Congreve rocket from the Nemesis struck the magazine of a large war junk, blowing it up in a shower of flying spars and seamen. Eleven junks were destroyed, two were driven aground and hundreds of Chinese sailors were killed within a few hours. Admiral Kwan, commander of the shattered fleet, had the red cap-button emblematic of his rank shot off by the British and was later relieved of the rank by his unsympathetic Emperor.

Keeshen hastened to notify Elliot that he stood ready to[22] hand over Hong Kong and the $6,000,000 indemnity. But even the shock of defeat had not flushed the Emperor from his dream world of superiority; he repudiated Keeshen’s agreement and ordered him to rally the troops for “an awful display of Celestial vengeance.” Well aware of the hopelessness of his situation, Keeshen tried to hold out by postponing his meetings with Elliot. Elliot, not to be put off this time, countered by opening a general assault along the Canton River. Within a month, his combined land and sea offensive had reduced every fort on the water route to Canton and his ships rode at anchor in front of the city.

British preparations to storm the city were well advanced when a fresh truce was arranged. The entire British force sailed back to Hong Kong, having retreated from almost certain victory. Elliot, however, felt no disappointment; he had never wanted to use more force than necessary to restore stable trade conditions. He feared that full-scale war would bring down the Chinese government, plunging the country into revolution and chaos.

Hong Kong had become de facto British territory on January 26, 1841, when the Union Jack was raised at Possession Point and the island claimed for Queen Victoria. Its 4,500 inhabitants, who had never heard of the Queen, became her unprotesting subjects.

The acquisition of the island produced ignominy enough for both sides; Keeshen was exiled to Tartary for giving it up and Elliot was dismissed by Palmerston for accepting “a barren island with hardly a house upon it,” instead of obeying the Foreign Secretary’s orders and driving a much harder bargain.

A succession of disasters swept over the colony in its first year of existence. “Hong Kong Fever,” a form of malaria thought to have been caused by digging up the earth for new[23] roads and buildings, killed hundreds of settlers. Two violent typhoons unroofed practically every temporary building on the rocky slopes and drowned a tenth of the boat population. The wreckage of the ships and buildings had scarcely been cleared away when a fire broke out among the flimsy, closely packed mat sheds. In a few hours, it burned down most of the Chinese huts on the island.

The flavor of disaster became a regular part of Hong Kong history. Its own four horsemen—piracy, typhoons, epidemics and fires—raced through the colony at frequent but unpredictable intervals, filling its hills and harbor with debris and death. There is still no reason to assume that they will not return, either singly or as a team, whenever the whim moves them.

Even imagining Hong Kong as an island bearing no more than a minimum burden of natural hazards, it is difficult to understand how it became settled at all. The London Times scorned it editorially in 1844 with the comment that “The place has nothing to recommend it, if we except the excellent harbor.”

The original colony and the much larger territory added to it in the next 120 years have no natural resources of value, except fish, building stone and a limited supply of minerals. Only one-seventh of its total area is arable land; at best, it can grow enough rice, vegetables and livestock to feed the present population for about three months of a year. There is no local source of coal, oil or water power. Fresh water was scarce in 1841, and in 1960, after the colony had constructed an elaborate system of fourteen reservoirs, the carefully rationed supply had to be supplemented with additional water bought and pumped in from Red China.

Hong Kong has an annual rainfall of 85 inches—twice that[24] of New York City—but three-fourths of it falls between May and September. At the end of the rainy season, ten billion gallons may be stored in the reservoirs but by the following May, every reservoir may be empty. Water use, especially during the dry winter, has been restricted to certain hours throughout the colony’s history. Running water, to the majority of Hong Kong’s poor, means that one grabs a kerosene tin and runs for the nearest public standpipe. Those lucky enough to reach the head of the line before the water is cut off may carry home enough to supply a household for one full day.

The industries of the colony, which expanded at a spectacular rate after World War II, could never have survived on sales to the local market. Most of its residents have always been too poor to buy anything more than the simplest necessities of food, clothing and shelter. No tariff wall protects its products from the competition of imported goods, but resentment against the low-wage industries of the colony continually puts up new barriers against Hong Kong products in foreign countries, including the United States.

From its thinly populated beginnings, Hong Kong has been transformed into one of the most dangerously overcrowded places on earth, with 1,800 to 2,800 persons jamming every acre of its urban sections. Eighty percent of its population is wedged into an area the size of Rochester, N.Y.—thirty-six square miles. About 325,000 people have no regular housing. They sleep on the sidewalks, or live in firetrap shacks perched on the hillsides or rooftop huts. A soaring birth rate and illegal infiltration of refugees from Red China add nearly 150,000 people a year.

Fire is the best-fed menace of contemporary Hong Kong. In the 1950-55 period, flash fires drove 150,000 shack and tenement dwellers out of their homes, racing through congested[25] settlements with the swiftness and savagery of a forest in flames. Tuberculosis attacked the slum-dwellers at the same ruinous pace. No one dares to predict what would happen if one of the colony’s older, dormant scourges—plague or typhus—were to break out again. But the colony found cause for relief and pride when a 1961 cholera scare was halted by free, universal inoculations.

More than a century of turmoil and privation has taught the colonists to accept their liabilities and deal with their problems, yet they prefer to dwell on the assets and virtues which have enabled them to endure, and in many cases, to prosper tremendously.

Hong Kong harbor has always been the colony’s greatest asset. Of all the world’s harbors, only Rio de Janeiro equals its spacious, magnificent beauty, with its tall green mountains sloping down to deep blue water. Perhaps Rio has a richer contrast of tropical green and blue, but the surface of Hong Kong harbor is so irrepressibly alive with criss-crossing ferry lines, ocean freighters riding in the stream, and tattered junk sails passing freely through the orderly swarm that it never looks the same from one minute to the next and is incapable of monotony.

An oceanic lagoon of seventeen square miles, the harbor lies sheltered between mountain ranges to the north and south and is shielded from the open sea by narrow entrances at its east and west ends. Vessels drawing up to thirty-six feet of water can enter through Lei Yue Mun pass at the eastern end of the harbor. Through the same pass, jet airliners approach Kai Tak Airport, roaring between the mountains like rim-rock flyers as they glide down to the long airstrip built on reclaimed land in Kowloon Bay, on the northern side of the harbor.

The intangible ramparts of the colony are as solid as its peaks: the sea power of the British and American navies, and the stability of British rule. At their worst, the colony’s overlords have been autocratic, stiff-necked and chilly toward their Chinese subjects.

The same British administrators who nobly refused to hand over native criminals for the interrogation-by-torture of the Chinese courts could flog and brand Chinese prisoners with a fierce conviction of their own rectitude. Nevertheless, they brought to China something never seen there before; respect for the law as an abstraction, an objective code of justice that had to be followed even when it embarrassed and discommoded the rulers.

Almost from its inception, the colony attracted refugees from China. Many brought capital and technical skills with them, others were brigands and murderers fleeing Chinese executioners.

Banking, shipping and insurance services of the colony quickly became the most reliable in Southeast Asia. Macao, in spite of its three-century lead on Hong Kong, was so badly handicapped by its shallow harbor, critical land shortage, and unenterprising government that it sank into a state of suspended antiquity. Hong Kong merchants, eager for new business, kept in close touch with world markets. Labor was cheap and abundant, still it was more liberally paid than in most of the Asiatic countries. Labor unions numbered in the hundreds, but they were split into so many quarreling political factions that they could rarely hope to win a showdown fight against the colony’s business-dominated government, although the Seamen’s Union did obtain many concessions after a long strike in 1922.

Notwithstanding the social gulfs between the British,[27] Portuguese, Indian and other national elements in the colony, all of them march arm-in-arm through one great field of endeavor; the desire and the capacity to make money. Hong Kong lives to turn a profit, and its deepest fraternal bond is the Fellowship of Greater Solvency.

Motivated by this common purpose, the British and Chinese dwelt together in peaceful contempt during the first fifteen years of the colony’s history, sharing the returns of a fast-growing world trade. The opium traffic resumed as though there had never been a war over it. The only enemy that worried the merchants became the Chinese pirates who preyed on their ships.

From Fukien to Canton, pirate fleets prowled the China coast. Two of their favorite hangouts were Bias Bay and Mirs Bay, within easy striking range of Hong Kong. With the arrival of the British, they began looting foreign merchant-ships with the same unsparing greed they had previously inflicted on Chinese ships and villages.

British warships, superior to the pirate craft in all but numbers and elusiveness, hunted them down with task forces. In four expeditions between 1849 and 1858, the Queen’s Navy sank or captured nearly 200 pirate junks. Thousands of prisoners were taken, and a fair share of them were hanged. British landing forces, storming up the beaches from the warships, leveled every pirate settlement they could find.

The land-and-sea offensive had a temporarily restraining effect, but new-born pirate fleets sprang up like dragon’s teeth to turn to the practice of seaborne larceny. A fifth column of suppliers, informers, and receivers of stolen goods within the colony obligingly assisted the pirates in plucking their neighbors clean. Hong Kong’s oldest industry has retained its franchise down to present times; in 1948, airborne pirates attempted[28] to high-jack a Macao-Hong Kong plane in flight. The plane crashed, killing all but one person who was detained and questioned, then released for lack of jurisdiction and sent back to China.

Piracy was the fuse that touched off a second Sino-British war in 1856, when the Chinese government charged that a Chinese ship manned by a British skipper was, in fact, a pirate vessel. While the skipper was absent from the Chinese lorcha, the Arrow, his entire crew was taken prisoner and accused of piracy by China.

The incident landed in the lap of Sir John Bowring, a former Member of Parliament and one of the most curiously contradictory of all colony governors. Philosophically a liberal and a pacifist, he was markedly sympathetic toward the Chinese. A prolific author, economist and hymn-writer, he had a brilliant gift for linguistics and was credited with a working knowledge of 100 languages, among them Chinese. He initiated wise and far-reaching improvements, including the first forestry program, which were enacted into law by later governors. With all these gifts, his five-year term (1854-1859) was marred by a series of hot and futile wrangles with his subordinates.

This mercurial man reacted to the capture of the Arrow’s crew by demanding an apology and their release. When the apology was not immediately dispatched, he assembled a military force and set out to capture Canton. War in India delayed the arrival of British reinforcements, and Canton withstood the assault. Meanwhile, Chinese collaborators in Hong Kong poisoned the bread supplied to Europeans; Bowring’s wife was one of scores of persons who suffered serious illness by eating the bread.

Shortly afterward the French joined forces with the English.[29] Canton and Tientsin were captured, and the Chinese government was forced to agree to add more trading ports to the five provided by the 1842 Nanking Treaty.

The ensuing short-term armistice was broken by sporadic Chinese attacks on British supply lines and a general resumption of hostilities, ending in the occupation of the Chinese capital at Peking.

The Kowloon Peninsula, jutting from the Chinese mainland to a point one mile north of Hong Kong Island, became involved in the war when its residents rioted against British troops encamped there. The British had considered the annexation of Kowloon for several years, realizing that if the Chinese decided to fortify it their guns would command Hong Kong harbor. Treating the riot as a compelling reason for taking possession, the British obtained an outright cession of the peninsula and Stonecutters Island, a little body of land about one mile west of Kowloon, under the terms of the 1860 Convention of Peking.

Bowring, meanwhile, had created a public Botanic Garden—still a beautiful hillside haven at the heart of the colony—laid down new roads and erected a number of public buildings. But his daily relations with other colony officials had degenerated into a battle-royal of insults and counter-accusations. The home government, appalled at Bowring’s un-British disregard for good form, rushed in a new minister to direct negotiations with China and replaced Bowring as governor with Sir Hercules Robinson, an unusually able colonial administrator. Bowring left the colony with his reputation at low ebb, snubbed by its English residents. The Chinese of Hong Kong, inured to snobbery but grateful for Bowring’s attempts to help them, saw him off with parting gifts.

Sir Hercules began his administration with a piece of good[30] fortune; practically all the contentious subordinates who had made Bowring’s tenure a long nightmare resigned or retired. The colony’s military leaders kept the pot simmering by demanding most of Kowloon for their own use, although Robinson wanted to preserve it for public buildings and recreational grounds.

In England, where the brimstone smell of the Bowring affair lingered for many months, the London Times was moved to describe the China outpost as a “noisy, bustling, quarrelsome, discontented and insalubrious little island” whose name was “always connected with some fatal pestilence, some doubtful war, or some discreditable internal squabble.” Robinson’s skirmish with the military attracted no more attention than a stray pistol-shot after a thundering cannonade.

Between wars and internal bickering, the colony was growing up. The California gold rush of 1849, followed by a major gold strike in Australia two years later, created a surge of prosperity as goods and Chinese laborers funneled through the port on their way to the goldfields. Japan was opened to world trade in 1853, and American whalers and seal hunters had begun to call at Hong Kong. Total shipping tonnage cleared through the port rose 1,000 percent in the fifteen years after 1848. With skilled labor and well-equipped dockyards at hand, the building, refitting and supplying of ships became the colony’s most important industry.

Overseas shipment of Chinese laborers from mainland China to perform work contracts in Central America, Australia, and the islands of the Indian Ocean created grave human problems.

Chinese were being kidnaped, abused like slaves and packed into the airless, filthy holds of sailing ships where they died at an alarming rate. From 1855 on, the colony imposed tighter and tighter restrictions on the trade, prescribing better[31] living conditions aboard ship and prosecuting kidnapers of labor. But the labor suppliers evaded the laws of the colony by taking on provisions at Hong Kong and calling at other ports along the China coast to shanghai contract workers.

The first of many waves of refugees to seek asylum in Britain’s “barbarian” enclave arrived with the outbreak of the Tai Ping Rebellion in 1850. Led by Hung Siu Tsuen, a Christian student, the rebels attacked the ruling Manchu Dynasty and fomented wild disorder in Canton. Thousands of apprehensive Chinese fled to Hong Kong, throwing themselves on the mercy of the foreign devils.

Governor Robinson and the land-hungry generals eventually compromised their conflicting claims to Kowloon real estate, but the colony government spent years of patient effort in straightening out the fuzzy, inexact and spurious titles to individual land-holdings on the peninsula. On the whole, British courts achieved a fair adjudication of claims.

Sir Hercules did not permit his administrative successes to alter the colony’s reputation for day-to-day blundering. He housed prisoners in a hulk off Stonecutters Island where it was accidentally swamped by an adjoining boat with a loss of thirty-eight lives. On a kindly impulse, he belatedly moved the hulk closer to shore, and a group of convicts ran down the gangplank to dry land and freedom.

Such oversights were exceptional; when Sir Hercules ended his term in 1865, he could look back on an administration which had put the unpopular colony on its feet by reforming its courts and modernizing and expanding its public works. This was no fluke, for he went on to similar successes in Ceylon, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa before being elevated to the peerage.

During its formative period, the colony was predominantly[32] a society of adult males. Its merchants and workers came from China to earn a living and to send their savings back to their wives and children; when they grew too old to work, they returned to their native cities and villages. But there was always a number of families among the population, and after the refugees began pouring in, the percentage of children rose. In 1865, children numbered 22,301 in a total population of 125,504. Only 14,000 of these were of school age, and less than 2,000 of them attended school.

Missionaries began to run schools for Chinese and European children almost from the time the colony was established, but the scale of their undertakings was modest. The Chinese organized native schools, and like the missionary ventures, floundered along with ill-trained teachers, inadequate buildings and loose supervision. Government schools, low in quality and enrollment, freed themselves of religious control in 1866. A private school with advanced ideas instructed Chinese girls in English, only to discover that its pupils were accepting postgraduate work as the mistresses of European colonists.

Five Irish governors, starting with Sir Hercules Robinson in 1859, ruled Hong Kong in succession, and three of them ranked among the ablest executives in its history. Each one was in his separate way a strong-minded, individualistic, and occasionally rambunctious chief. After the Hibernian Era came to an end in 1885, no later governors emulated their mildly defiant gestures toward the home government.

Sir Richard Graves Macdonnell, second of the Irish governors, was a tough and seasoned colonial administrator who tackled the unsolved problems of crime and piracy with perception and vigor. He saw that naval action against the pirate fleets would bring no lasting results while the sea-raiders had[33] the assistance of suppliers, informers and receivers of stolen goods within the colony. He put all ship movements in Hong Kong waters under close supervision, and assigned police to ferret out every colonist working with the pirates. To a greater degree than any of his predecessors, he succeeded in checking piracy, but no governor has ever stamped it out.

Macdonnell also intensified the campaign against robbery, burglary and assault. Commercial interests applauded his increased severity in the treatment of prisoners and his frequent reliance on flogging, branding and deportation of offenders. Macdonnell himself saw no contradiction between such rough-shod methods and, on the other hand, his generosity in donating crown land for a Chinese hospital where the destitute and dying could be cared for in a decent manner. Previously, relatives of ailing, elderly paupers had deposited them in empty buildings with a coffin and drinking water, leaving them to suffer and die alone.

Sir Arthur Kennedy, who followed Macdonnell, was one of the colony’s most popular governors. He knew his job thoroughly and he combined this knowledge with sound judgment, a lively sense of humor, and a rare talent for pleasing the traders and the Colonial Office. He initiated the Tai Tam water-supply system and continued Macdonnell’s relentless fight against crime.

Kennedy threw his more orthodox colleagues into a dither by entertaining Chinese merchants at official receptions in Government House, his executive residence. He went so far as to invite these Chinese to suggest improvements in the laws of the colony, and they promptly asked for a law to punish adulterous Chinese women. Knowing that each of the petitioners had several wives and concubines, Sir Arthur realized[34] that his volunteer legal advisers were actually looking for government sanction to hobble their restless bedmates. He tabled the petition with tact.

External changes produced surprising mutations in the progress of the colony. Its isolation diminished with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the completion in the next year of direct overland telegraph connection with England. No longer was a governor left to his own devices for days and weeks, improvising policy at the peril of his job until orders arrived from home.

The hazards of life on the South China coast remained. In 1874, the colony was devastated by the worst typhoon since 1841. Flying rooftops filled the skies above the island, and 2,000 Chinese fishermen and their families drowned in the ruins of their floating villages.

Sir Arthur’s departure to become the Governor of Queensland was a melancholy time for the colony’s Chinese. They were openly devoted to him—the first governor who had treated them more or less as equals. Even the English liked him, and he became the first and only governor to have a statue erected to his memory in the colony’s Botanic Garden. The statue disappeared during the Japanese Occupation of World War II.

Kennedy’s successor, Sir John Pope Hennessy, not only preserved this solicitude for the Chinese but provoked a storm of protest from European residents by practicing leniency toward Chinese prisoners. When murders and burglaries increased, his humanitarian policies were blamed. Hennessy, a resourceful debater who was at his best in defending his own policies, was not intimidated. The weak side of his administration showed in a quite different area—his habitual neglect of essential paper work.

Hennessy’s friendliness toward the Chinese unexpectedly involved him in controversy with the Chinese themselves. For centuries, wealthy Chinese families had “adopted” little female domestic slaves by purchasing them from their parents or relatives. In the households of the rich, these Mui Tsai could be identified at once by their shabby clothing and their general appearance of neglect.

Even families of limited means purchased Mui Tsai, so that the mother of the family could take a job outside her home while the juvenile slavey cared for the children and contended with the simpler household drudgery. For the poorest families, sale of a daughter as a Mui Tsai was the natural solution to an economic crisis. But the institution, unacceptable to Western eyes from any aspect, had become the vehicle for gross abuses—the kidnaping and sale of women as prostitutes in Hong Kong or for transportation overseas. Kidnapings had become so numerous and flagrant by 1880 that Governor Hennessy and Sir John Smale, the colony’s Chief Justice, condemned the Mui Tsai system as contrary to British law.

The Chinese protested that Mui Tsai was not slavery; it was an ancient, respectable adjunct of family life. Indeed, it was quite humane, for it saved the daughters of many impoverished families from being drowned. The English didn’t want that, did they? The Chinese offered no defense of kidnaping and forced prostitution arising from the institution of Mui Tsai.

Under pressure of the colony government, influential Chinese set up the Po Leung Kuk, or Society for the Protection of Virtue, to rescue women and girls from flesh peddlers, provide a home for them in a section of the Chinese-operated Tung Wah Hospital, and train them for respectable occupations.

Hennessy, like Governor Bowring, entangled himself in a[36] series of acrimonious disputes with other colony officials, antagonizing them in groups by lashing out at the school system, prison maladministration and the harsh treatment of convicts. His most combative foe was another Irishman, General Donovan, head of the colony’s armed forces. Their verbal Donnybrook erupted over the perennially thorny question of how much Kowloon land the military was entitled to.

General Donovan hit back at Hennessy with a sneak attack; he complained to the home government about the outrageous sanitary conditions in the colony—the lack of proper drainage, the polluted seafront, and the verminous tenements where entire Chinese families shared one room with their pigs and other domestic animals. All these conditions had existed in Hong Kong since 1841, but no one had called them to the home government’s attention with the holy indignation of Donovan.

Osbert Chadwick was sent from England to investigate and he found sanitary conditions every bit as bad as Donovan had described them. Chadwick’s report became the basis, after long postponement and inaction, for the creation of a Sanitary Board and fundamental sanitary reforms.

Hennessy left the colony in 1882 to become Governor of Mauritius and to lock horns with a new team of associates. Four administrators and two governors passed through the colony’s top executive position in the next decade, but none effected any substantial improvements in sanitation. Every attempt to clean up pesthole tenements was balked by cries of persecution and government interference from the landlords; they would consent to no improvements unless the government paid their full cost.

In other directions the colony advanced steadily. It completed[37] a new reservoir system and central market and rebuilt the sewage and drainage system. Ambitious land-reclamation projects were pushed ahead at Causeway Bay and Yau Ma Tei to meet the unabating demand for level sites in the crowded, mountainous colony. Kowloon, a wasteland of undulating red rock, in the 1880s began cutting down its ridges and using the spoil to extend its shoreline—a process that continues at an amazingly accelerated rate today.

Hong Kong has never known an age of serenity; its brief interludes of comparative calm have always been followed by cataclysmic upheavals. In the spring of 1894, the colony was invaded by plague, long endemic on the South China coast. Within a few months, 2,485 persons had died of pneumonic, septicemic and bubonic plague, and Western medicine had no more power to check it than had Chinese herb treatments.

The onset of plague was so terrifying that long-deferred sanitary reforms were rushed through and rigidly enforced. Deaf to the protests of all residents, British military units began regular inspections of Chinese homes. Sanitary teams condemned 350 houses as plague spots and evicted 7,000 persons from infected dwellings. Resenting foreign invasion of their privacy and mistrustful of Western medicine, the Chinese retaliated by posting placards openly in Canton and furtively inside the colony accusing British doctors of stealing the eyes of new-born babies to treat plague victims.

Business came to a stop and ships avoided the plague-stricken port. The plague abated for a year, then returned in 1896 to take another 1,204 lives. The Chinese kept up a rear-guard action against sanitary measures with strikes and evasions, hiding their dead and dying or dumping their bodies in the streets and harbor. Sometimes they exposed their dying[38] relatives on bamboo frames stretched across the narrow streets, hoping that the departing soul would haunt the street instead of its former house.

The benighted traditionalism of the colony’s Chinese awoke the British administration to one of its most serious weaknesses; a half-century of British rule had failed to give to 99 percent of the colony’s residents any clear idea of the civilization they were expected to work and live under. The tardy lesson eventually took effect, and the British embarked on a long and intensive program of improving and enlarging their school system. In the Tung Wah Hospital, English and Chinese doctors learned to their surprise that therapies unlike their own were not necessarily sheer quackery, and that they could work together for the benefit of their patients.

With the population of the colony exceeding 160,000 in the early 1880s, military and commercial leaders turned to the possibility of acquiring more land on the Chinese mainland. They pressed the British Foreign Office to seek the territory running north from the Kowloon Peninsula to the Sham Chun River, about 15 miles away. The suggestions were rejected as prejudicial to Sino-British relations until other foreign powers started to thrust into Chinese territory for commercial concessions and spheres of political influence.

France, Russia and Japan were the spearheads of this infiltration of the Celestial Empire, which had been weakened by internal rebellion. Japan defeated China in the 1894-95 war and exerted ever-stronger commercial control over the mainland. Russia made its bid by advancing through Manchuria and occupying Port Arthur. Germany hastened to join the commercial invaders. Hacked at from four directions, the Chinese people attempted to close ranks in defense of their homeland.

The United States, with no apparent desire to annex Chinese territory, nevertheless heightened both British and Chinese apprehension by launching its naval attack on Manila from Mirs Bay in May, 1898. The Chinese feared another land grab, and the British felt they could best protect Hong Kong if they were able to deal with a strong, unified China.

Despite its earlier reluctance to disturb the status quo, Great Britain was now convinced that it had to acquire the territory between Kowloon and the Sham Chun River as a protective buffer for Hong Kong. On July 1, 1898, Britain obtained a 99-year lease to this mainland territory and 235 adjacent islands with a total land area of 365½ square miles.

Chinese guerrilla forces in the New Territories—as this leased area is still called—opposed the British occupation but were defeated and driven out by British troops in a ten-day campaign. That was the easiest part of it. It took four years of wrangling with the uncooperative Chinese residents to establish valid titles to private plots of land in the New Territories. Kowloon City, an eight-acre patch on the border of Kowloon and the New Territories, became a kind of orphan in the transaction, with the British firmly insisting it was part of the lease and the Chinese arguing somewhat inconclusively that it was not. Nationalist China claimed it as recently as 1948, but Red China has not so far pushed a similar claim. Britain regarded it as hers in 1960, and sent in her police to clean out the robbers and murderers who had long used it as a hiding place.

A general deterioration of Sino-British relations followed the leasing of the New Territories. The two empires were at odds over the maintenance of Chinese customs stations in the New Territories, the presence of Chinese warships in Kowloon Bay and the treatment of Chinese prisoners in Hong Kong[40] jails. Moreover, each disagreement was intensified by the patriotic fervor which led to the Boxer Rebellion.

At the opening of the twentieth century, the Chinese Empire had been driven into a hopeless position. Bound and crippled like the feet of her women, she had neither the weapons nor the industrial capacity to repel the encroaching armies of Europe and Japan. By any reasonable standard, she was beaten before she started to fight back.

Out of China’s desperation grew a super-patriotic secret society, The Fist of Righteous Harmony, or Boxers, who claimed that magical powers sustained their cause, making them invulnerable to the superior weapons of foreigners. Occult arts and a rigorous program of physical training, the Boxers professed, would carry them to victory. It was a crusade of absurdity; foolish and foredoomed, but plainly preferable to unresisting surrender.

The Boxers opened their offensive by murdering missionaries and Chinese Christians, causing a new rush of refugees to Hong Kong. They burned foreign legations in Peking and sent the surviving Chinese Christians and foreigners fleeing to the British legation for safety. An international army, composed of French, German, Russian, American and Japanese units, lifted the siege of the legation on August 14, 1900, and remained in Peking until peace was signed eleven months later.

Recurrences of plague killed 7,962 persons in the colony at the turn of the century, but the discovery that plague was borne by rats prompted a war to exterminate them. Rewards of a few cents were paid for their carcasses, and profit-hungry Chinese were suspected of importing rats from Canton to claim the bounty. The threat of plague gradually decreased,[41] but malaria, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and cholera remained to ravage the refugee-jammed colony.

On September 18, 1906, a two-hour-long typhoon hit the colony without warning, drowning fifteen Europeans and from 5,000 to 10,000 Chinese. No one could accurately estimate the deaths, which were concentrated among the fishermen and boat people, but nearly 2,500 Chinese boats of all types were hammered into kindling wood or sunk without trace. Fifty-nine European ships were badly damaged and a French destroyer broke in two. Piers and sea walls were breached and undermined, and 190 houses were blown down or rendered uninhabitable. Roads and telephone lines were washed out, farm crops and tree plantations were laid low by the power of the worst storm in local history. Damage estimates ranged far into the millions.

In the aftermath of the typhoon, all elements of the population cooperated to raise a relief fund. The money collected was used to repair wrecked boats, recover and bury the dead, feed and house the homeless and provide for the widows and orphans of storm victims. (The horror of this catastrophe was reenacted on September 2, 1937, when a typhoon and tidal wave engulfed a New Territories fishing village, drowning thousands.)

The dawn of the twentieth century marked the final collapse of the Celestial Empire. Dr. Sun Yat Sen, who had been banished from Hong Kong in 1896 for plotting against the Chinese government, steadily intensified his revolutionary activities until, in 1911, he led the revolution which overthrew the tottering monarchy and replaced it with the Republic of China. The unrest that accompanied this violent change-over caused more than 50,000 refugees to cross the Chinese border into British territory.

The transition from empire to republic did not end China’s internal turmoil, and for many years afterward its political disturbances were felt in Hong Kong. Piracy flourished in the waters around the colony; one band of corsairs set fire to a steamship, causing the deaths of 300 passengers. Brigands and warlords preyed on southern China, sometimes making forays across the colony’s border to pounce on villages in the New Territories. China was torn by political struggles during the 1920s, and these provoked strikes within the colony and Chinese boycotts of Hong Kong goods. All through this period, refugees poured across the border in unending lines.

The worldwide depression of the 1930s brought a sharp drop in colony trade, but the government created jobs for thousands with road-building and other public works.

Japan opened its war against China in 1937, and within a year Hong Kong was bursting with the addition of 600,000 refugees. Poverty and overcrowded housing offered ideal conditions for epidemics of smallpox and beriberi which killed 4,500 persons in 1938. Still, the total population climbed to 1,600,000. Government refugee camps housed about 5,000 people; another 27,000 regularly slept in the streets.

Emboldened by victories in China and an alliance with Nazi Germany, the Japanese militarists launched their “Greater Far Eastern Co-Prosperity Sphere” by attacking Hong Kong, Pearl Harbor and the Philippines on December 7-8, 1941. Crossing the Chinese border at Lo Wu in the New Territories, two Japanese divisions supported by overwhelming air power invaded and conquered the colony within three weeks. They proceeded without pause to loot its warehouses and strip its factories of machinery for shipment to Japan.

The Japanese imprisoned the remaining British residents and raped and pillaged at will. By torture, starvation, and main[43] force they drove a million Chinese residents from the colony and maintained a merciless control over the survivors by propaganda, intimidation, imprisonment and the use of Chinese fifth-columnists.

With their smashing victories in the Philippines, East Indies and at Singapore, the Japanese should have found it comparatively easy to unite Asiatics against the whites who had once lorded it over them. But they suffered from the same compulsion as the Germans; at a time when they had a chance to win allies among the people they had conquered, they botched it by senseless cruelties. When their firecracker-like string of victories had burned out, they had gained no friends, but instead had earned millions of new enemies.

Nearly four years passed before the Japanese were beaten into unconditional surrender and the British rulers returned to Hong Kong. Their return had a kind of spectral quality as the British Pacific Fleet, commanded by Rear Admiral C. H. J. Harcourt, steamed through Lei Yue Mun pass, gliding under the silent muzzles of Japanese guns emplaced along the mountainsides with their crews standing at attention beside them.

This was on August 30, 1945. The British went ashore to find thousands of their countrymen and other Allied prisoners gaunt and starving in prison camps. Many had been crippled and deformed by torture. Others had been killed in Allied bombing raids on Hong Kong. Seven large and seventy-two small ships had been sunk in the harbor, 27,000 homes had been destroyed. The fishing fleet was in ruins and the fishermen were in rags. Nine-tenths of the surviving residents were dead broke, while a few collaborators and black-marketers had accumulated fortunes. Livestock had virtually disappeared. Millions of carefully cultivated trees, planted to[44] check erosion and retain the run-off of tropical rainfall for drainage into the reservoirs, had been chopped down to provide firewood. Schools were almost entirely suspended. Railroads and ferry lines were in an advanced stage of disrepair. Disease and crime had reached their highest rates in many years.

The British, who are inclined to procrastinate in the solution of small crises, can be indomitable in the face of major emergencies. Within six months after reoccupying the colony they had restored its government and society to working order. Six years after the British return, the colony was more prosperous, more congested, and more progressive than it had ever been before.

Nationalist China was driven from the mainland in 1949, and a new Communist state took its place. Britain promptly recognized Red China as the ruling power on the mainland, but relations between the Chinese Reds and Hong Kong were strained by Communist-caused disturbances in the colony and shooting “incidents” at sea and in the air. There was no apparent danger of war, however. In 1951, the colony’s trade amounted to $1,550,000,000, the highest point it had ever reached.

If there were signs of complacency in Hong Kong, they were erased by the outbreak of the Korean war. The United Nations clamped immediate restrictions on the colony’s trade with Red China, and Red China slashed its imports from Hong Kong. Trade volume declined still further when Hong Kong voluntarily halted its exports to Korea and the sending of strategic materials to Red China. The United States at first included Hong Kong in its embargo of all trade with Red China, but the colony prevailed upon America to ease the ban. America agreed to accept goods from Hong Kong, provided[45] that they were accompanied by a Certificate of Origin attesting that they were made in Hong Kong and had not simply been transshipped from Communist China through the colony.

With the China market gone, as well as Hong Kong’s traditional role as a transshipper to and from China, the colony executed its most spectacular economic somersault since 1841; it switched from trading to manufacturing. In six years, the great entrepôt became an important industrial producer. By 1962, over 70 percent of the goods it exported were made in the colony, and about half its workers were employed in industry.

Having performed this overnight flip-flop without suffering an economic set-back, Hong Kong has become more prosperous than ever. Except that it has too many people, hasn’t enough land to stand on, can’t raise enough food or store enough water, is incessantly harried by rising tariffs and shipping costs, and has no idea what its testy, gigantic neighbor to the north will do next, Hong Kong would appear not to have a worry in the world.

“When one reads of 1,000,000 homeless exiles all human compassion baulks and the great sum of human tragedy becomes a matter of statistical examination.”

—“A Problem of People,” Hong Kong Annual Report, 1956

From the end of World War II until the fall of 1949 the mainland of China rumbled with the clash of contending armies. Thousands of Chinese, uprooted and dispossessed by the Nationalist-Communist struggle, streamed southward across the Hong Kong border in a steady procession.

The orderly nature of the exodus ended when Mao Tse-tung, having beaten and dispersed the Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek, turned his guns on all people suspected of thinking or acting against the People’s Republic of China. What had been a slow withdrawal became a headlong flight for life.

For six months after the Reds took over the mainland,[48] Hong Kong clung to its free-immigration policy. Then it reluctantly adopted a formula of “one in, one out”—accepting one immigrant if another person returned to China. But the refugee flow continued at a reduced rate in spite of land and sea patrols on both sides of the international boundary.

In 1956, the British relaxed immigration rules for seven months, hoping the refugees would go home. Instead, 56,000 new refugees arrived from China, and the colony reimposed its restrictions.

The Chinese side of the frontier unexpectedly opened in May, 1962, and 70,000 refugees dashed for Hong Kong. The colony, alarmed and already desperately overcrowded, strengthened and extended its boundary fence and returned all but 10,000 of the new arrivals to China.

This race for freedom aroused the Free World’s tardy compassion. The United States moved to admit 6,000 Hong Kong refugees, including some who had applied for admission as long ago as 1954. Taiwan, Brazil, and Canada also expressed willingness to accept a limited number. Until this change of heart, Taiwan had taken only 15,000 colony refugees, and the United States only 105 a year. None of these offers will materially reduce the number of Hong Kong refugees, whose total is officially estimated at 1,000,000. Unofficial estimates set the total around 1,500,000.

Whatever the total within this range, it stuns the imagination. The well-intentioned observer who has come to sympathize finds himself backing away from this amorphous mass, unable to isolate or grasp its human content of individual misery, privation and heartache. He wants to help, as he would do if he saw a child struck down in the road, but when the whole landscape is a panorama of tragedy, he hardly knows where to begin.

There are a dozen landscapes like that in Hong Kong; the hills of Upper Kowloon with thousands of flimsy shacks perched uncertainly on their steep granite faces; the heights above Causeway Bay where squatter settlements flow down the mountainside like a glacier of rubbish; the rooftops of Wanchai, maggoty with close-packed sheds; the rotting tenements of the Central District strewn in terraces of misery across the lower slopes of Victoria Peak; the sink-hole of the old Walled City in Kowloon with its open sewers and such dark, narrow alleys that its inhabitants seem to be groping around in a cave with a few holes punched through the roof.

Yet there are people in the colony who have chosen to cut their way through this thick tangle of indiscriminate suffering. Going beyond that first fragile desire to help and the secondary conclusion that no one person can do anything effective against a problem of such vast dimensions, they have learned to stand in the path of an avalanche and direct traffic. They have opened a way to solve the refugee problem by the simple process of starting somewhere. Ultimate solutions, in the sense of housing and feeding all the refugees by giving them productive jobs in a free economy, lie many years and millions of dollars away. Meanwhile, people of courage and resolution, dealing with individual human needs instead of wallowing in statistics, have achieved wonders in improving the lot of Hong Kong’s refugees. Who they are and what they have done offer the real key to Hong Kong’s problem of people.

Sister Annie Margareth Skau, a Norwegian missionary nurse of towering physical and spiritual stature, began her work among Hong Kong’s refugees with invaluable postgraduate training. She herself was a refugee from China, driven out by the Reds.

Born in Oslo, she studied nursing at its City Hospital and decided to become a “personal Christian,” dedicating her life to labor as a missionary nurse of the Covenanters, or Mission Covenant Church of Norway. The work was certain to be arduous, for the Covenanters sent their workers to such remote corners of the world as Lapland, the Congo or the interior of China. Annie, who has an almost mystical intensity of religious faith, had no qualms about her probable assignments. Besides, she looked about as large and indestructible as Michelangelo’s Moses, and possessed a temperament of ebullient good nature.

After serving successfully in several other missions, she was sent to China in the late 1930s. Establishing herself at a mission in Shensi, northeastern China, she was the only Western-trained medical worker among the 2,000,000 residents of this agricultural region. In all likelihood, she was the largest woman ever seen by the Chinese children under her care—over six feet, four inches tall, with a Valkyrie’s frame—but so gentle that none of the children were awed by her presence. Her appearance anywhere was a signal for laughter and games; she never seemed too tired to play with children and teach them little songs.

Invading Japanese armies passed within two miles of her mission and clinic in 1938, but none of the villagers ever betrayed the foreigner’s presence. She had a quick, retentive mind, and learned to speak Mandarin Chinese almost as well as she knew her own language. On the rare occasions when an English-speaking visitor reached the out-of-the-way settlement, he was surprised to find Sister Annie speaking his language quite capably. Throughout the war and into the postwar era, she continued to bring Christianity and expert medical care to her adopted people.

When the Communists seized control of China, however, the Christian missionaries were doomed. The Christian God became a hateful image in a shrine reserved for Lenin, Stalin and Mao Tse-tung, and a beloved missionary nurse in a farming village was transformed into an enemy of the people. The commissars and their lackeys began by hedging Annie about with arbitrary regulations, then they confiscated medical supplies intended for her patients.

None of these measures succeeded in halting her work. Exasperated at their failure, the local party leaders finally dragged her before a kangaroo-style People’s Court. The word had been passed that any villager who arose to denounce her for crimes against the state would be handsomely rewarded. Not a single accuser appeared. Having lost face before the entire village, the Reds were more determined than ever to punish her.

If no one who knew Sister Annie could be lured into a denunciation of her, the obvious solution was to haul her off to a distant village where no one knew her. Having done this, the Reds threw her into jail as an object-lesson to anyone who befriended Christians. An old woman, knowing nothing of Annie but remembering the humane work of other missionary nurses in the village, begged the Communists to put her in jail with the foreign prisoner so that she could comfort her.

“Even the guards were kind to me,” Annie recalls. “The village people didn’t jeer at me or try to hurt me; they kept trying to pass food to me. They were loyal to the last minute!”

Under the relentless persecution and mistreatment, Annie’s strong body broke down, and in the summer of 1951, she was close to death from pneumonia and malaria. The Reds, who refused to let her leave the country when she was well, hurried[52] to get rid of the ailing woman. Exhausted and gravely ill, she left China and returned to Norway for a long rest and the slow regaining of her normal health.

Eighteen months later she came back to Asia knowing that she would never be readmitted to a Communist China. But there was still work to be done, and she turned her efforts to a squalid shacktown in Hong Kong called Rennie’s Mill Camp.

Three years earlier the routed remnants of Chiang’s army, left behind on the mainland, had thrown together a cluster of shacks beside Junk Bay, a backwater of the British colony without roads, water, light or sanitation. Nearly 8,000 persons, wounded soldiers and their wives and children, camped haphazardly on the steep shores of the bay, ran up the Nationalist flag and claimed the forlorn site as their own.

When Annie reached the camp in March, 1953, traveling by sampan and clambering over the high hills like a lost Viking, she found it haunted by despair; a dirty, disease-ridden place, dragged down by the decline of the Nationalist cause. Another nurse had started a small clinic in a wooden hut, eight by ten feet in floor area, which treated 600 patients a day. Annie and the other nurse shared sleeping quarters in a cubicle attached to the hut.

Sometimes the cases were so numerous and critical that the two nurses put the worst cases in their own cramped beds and spent the night on their feet treating other patients. Their medical equipment consisted of one thermometer, a few antiseptics and dressings, and a rickety table that wobbled groggily on the half-decayed floorboards.

With the approach of Christmas, 1953, the fortunes of the clinic sank to a new low. Both nurses were quite broke, unable to buy the food and medical supplies their patients needed so critically. Acting more from faith than reason, Annie set[53] out to pick her way over the precipitous rocks to Lei Yue Mun pass and cross by sampan to Hong Kong Island, hoping to beg for help.

To her delighted surprise, the mission’s post-office box on the island produced a windfall—$200 in contributions from ten persons overseas. Charging into the shopping crowds, Annie spent every cent on food and medicine. She scarcely noticed the weight of her purchases as she trekked the hard route back to Rennie’s Mill. Until three o’clock Christmas morning, the two nurses were on their feet, handing out life-saving presents and exchanging holiday greetings in Mandarin and Cantonese.

“The money problems weren’t so bad after that,” Annie says. “Gifts came in from welfare organizations and individuals, and we were able to build a little stone clinic and a home for ourselves.”

At the same time, health problems grew worse at Rennie’s Mill. Drug addiction and tuberculosis spread through the camp as its inhabitants abandoned hope of an early return to China.

“Bad housing and poor food started the TB,” she explains. “But it got much worse when people gave up hope, or heard about their relatives being killed by the Communists. Chinese people are devoted to their parents, and to be separated from them, or learn they’ve been killed—it’s heartbreaking.

“That was when we realized we’d have to build a rest home for those patients,” Annie says. “We didn’t have any money; all we had was a mission to do the best we could. One day I boarded a sampan with a group of children and we rowed out into Junk Bay until we came to a little inlet. I saw a hill just above us, jutting right out to the shore. I knew right then we would build our chapel on that hill.”

Annie discusses the incident with the fervor and conviction of one who has received a private revelation.

“I saw the whole rest-center arranged around that chapel almost as if it were already completed, built around love. I had no idea where the money was coming from, not any kind of an architect’s plan, but it didn’t matter. I knew that Christ would find a way.”

A way began to appear when a nurse who had worked with Sister Annie visited the United States in 1954, telling children in Wisconsin schools about their work. The response was electrifying. One small boy stood up beside his desk to announce with utter seriousness, “I want to give my heart to Jesus.” The appeal spread like a prairie fire; by February, 1955, Wisconsin school children had sent more than $2,500 for the new rest home, which was called Haven of Hope Sanatorium. An anonymous contributor donated another $5,000 through the Church World Service, Hong Kong welfare agency of the National Council of Churches of Christ in America.

“Now our sanatorium had walls and a roof,” Annie says. “So we prayed for furniture and food for our patients—and for bedpans, too.

“It was a hand-to-mouth existence,” she remembers without a trace of self-pity. “Our staff had no resources—we were so short of staff that some of us worked for two years without a day off. We didn’t mind it at all; we worked with one mind and one spirit, as if that sanatorium and what it stood for was our one reason for living.”

In its early stages, the sanatorium was nothing more than a rest home. One day, almost as an afterthought on a busy round of duties, Annie asked a few of her patients to help her with some routine tasks. They pitched in at once and returned the following day to volunteer for more duties. They kept at[55] the work for several days, then called on Annie in a kind of delegation.

“Give us instructions, show us what to do,” they respectfully demanded. “We want to learn how to be real nurses.”

Annie agreed, taking care to see that none of the volunteers exerted themselves beyond the limits of their precarious health. After three months, they insisted on examinations to show what they had learned.

From modest and tentative beginnings, the courses multiplied and expanded into a full-scale nursing school, offering a two-and-a-half-year progression of classes in eleven different subjects, with stiff exams. Most of the pupils are girls between eighteen and twenty who specialize in TB nursing. The eleventh class was graduated in February, 1962, and the demand for new enrollments was so brisk that Annie, as Director of Nursing Services, could accept only five out of sixty eager applicants.

The sanatorium grew into a 206-bed institution of modern and spotless appearance, and a 40-bed rehabilitation center for chronic and infectious TB patients has been built nearby. Church World Service cut a road through to the isolated site and it was later paved by the colony government. Tuberculosis has been brought under control at Rennie’s Mill Camp, and the Haven of Hope is drawing many of its patients from outside. There is no danger of a shortage; TB strikes everywhere among Hong Kong’s poor.

Haven of Hope is administered by the Junk Bay Medical Council, which also operates a clinic at Rennie’s Mill. Four doctors comprise the sanatorium staff. Except for Annie and Miss Martha Boss, the assistant matron, from Cleveland, Ohio, all the nurses are Chinese. Miss Boss, trained in the same diligent tradition as Annie, spends three days a week at the[56] sanatorium, three days on church work and school duties in Rennie’s Mill, and the seventh day on an industrial medical project.

Rennie’s Mill Camp no longer looks like a shacktown. Catholic and Protestant mission schools have been established, and many residents are employed in handicraft shops. A new police post has been erected beside the camp, and a bus line carries camp residents to the business and shopping districts of Kowloon. Soon a reservoir is to be constructed with government aid on a hill above the camp, and a modern housing development will replace inadequate dwellings.

Taiwanese flags still fly in the breeze at many places in the camp, and Nationalist Chinese contribute to its support. But its main lease on life comes from the churches and the colony of Hong Kong.

Although the scope of Annie’s activities has become much wider, she has lost none of her personal and religious attitude. When she walks through the wards she is followed by the smiles of hundreds of children. At any moment, she will stop to lead a grinning group of little girls, perched on their beds like sparrows, in a song. With Annie joining in the gestures, the kids sing out in Cantonese “Jesus loves little children ... like me ... (pointing to themselves) ... like you ... (pointing at Annie or the girl in the nearest bed) ... like all the others” (with a big, wide-open sweep of the arms).

Annie hugs a lively, black-haired youngster and says quietly, “Her mother was seven months pregnant when she swam from China to Macao with this little one on her back. The girl’s been here two years, and she’s gradually getting better. Her mother went back to China, and has probably been liquidated by the Communists.”

Another girl reacts to Annie’s pat on the head with the wiggly cordiality of a puppy.

“This little one was scared to death of ‘imperialists’ when she came here,” Annie explains. “It took us a long time to persuade her that the Red propaganda wasn’t true.”

Her first two patients at Haven of Hope, a brother and sister, have now completely recovered. Both had seen their parents tortured and killed by the Reds.

“When the girl came to us, her face was like stone,” Annie says. “For two years I played with her, trying all kinds of funny things to bring her out of that frozen stupor, but she never smiled once.

“I wasn’t getting anywhere,” she continues. “Then I tried something different. On July 6, 1955, I put her in a sampan with eleven other kids, and took them all to see the wonderful new building we’d just finished. You know, the first time she got a look at it she broke into a big smile! It was the first time she looked happy. Now she’s fourteen, and her greatest ambition is to be a nurse.”

A magnificent chapel, built exactly where Annie had visualized it, was completed in time for Christmas services in 1961. A group of Norwegian seamen donated an illuminated cross to surmount its roof. At night, when their ships sail out from Hong Kong, they can see it glowing above a line of hills that cut back from the sea like the fiords of Norway.

To Annie, the chapel embodies the same spirit she expressed in naming the eleven wards at Haven of Hope Sanatorium: Love, Peace, Joy, Patience, Kindness, Goodness, Faithfulness, Neatness, Temperance, Hope and Courage.