The Project Gutenberg EBook of Puck's Broom, by E. Gordon Browne

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

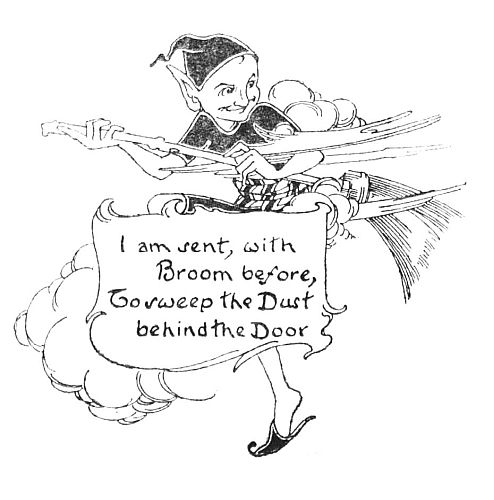

Title: Puck's Broom

The wonderful adventures of George Henry & his dog Alexander

who went to seek their fortunes in the Once upon a time land

Author: E. Gordon Browne

Illustrator: Kathleen I. Nixon

Release Date: December 11, 2020 [EBook #64012]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUCK'S BROOM ***

Produced by Tim Lindell, Jane Robins, George A. Smathers

Libraries (University of Florida) and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's note

Corrected various punctuation.

The wonderful adventures

of George Henry & his dog Alexander

who went to seek their fortunes in

the ONCE UPON A TIME Land....

By

E. Gordon Browne

Illustrated by

Kathleen I. Nixon

New York

Moffat Yard & Company

1923

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY THE RIVERSIDE PRESS LIMITED EDINBURGH

PAGE

GEORGE ARRIVES 17

How George Henry came into the world, and what Puck and the fairies thought about it. Some wise words about nurses and parents. Alexander the Greatest appears for the first time. Why George did not believe in the fairies.

GEORGE GROWS UP 29

All about the birthday party. A particularly jolly tea with special games and fireworks. All about the other fireworks, which were quite a surprise. How the fairies meant to invite George to their party, and what the old frog said.

MIDSUMMER EVE 41

The fairy invitation arrives. George's first pair of trousers. Midsummer Eve and the preparations for the fairy party. Puck's anger, and the nasty things that the old frog said. What happened at the party in the wood.

DREAM-MUSIC 53

George is ill and very cross. His wonderful dream. What was it all about? What the doctor said to him about the fairies. "Perhaps there is and perhaps there isn't." The fairies listen to a story. "To-night!" George hears the dream-music.

THE LAND OF DREAMS 65

George and Alexander set out in search of adventure. The dream-music calls to him again. Can dogs talk? "Wish as hard as ever you can!" Just like a bit of a story-book! The little green gate. The delightful little house in the wood, and the tea waiting there for George and Alexander. The Land of Dreams.

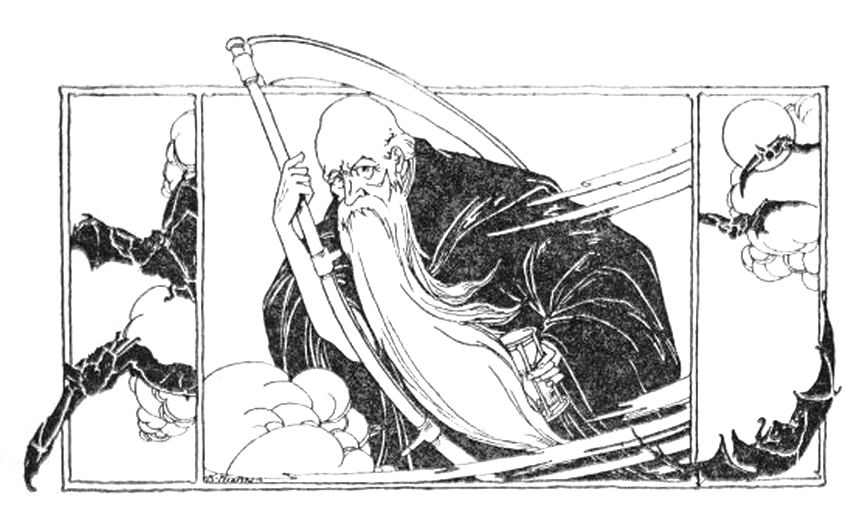

FATHER TIME 77

George's house. The twisty-curly paths which led to the sea. The old man sitting on the seashore. The hour-glass. "Are you Father Time, please?" "A stitch in time saves nine." "Follow your fortune, little George!" And it was Puck after all!

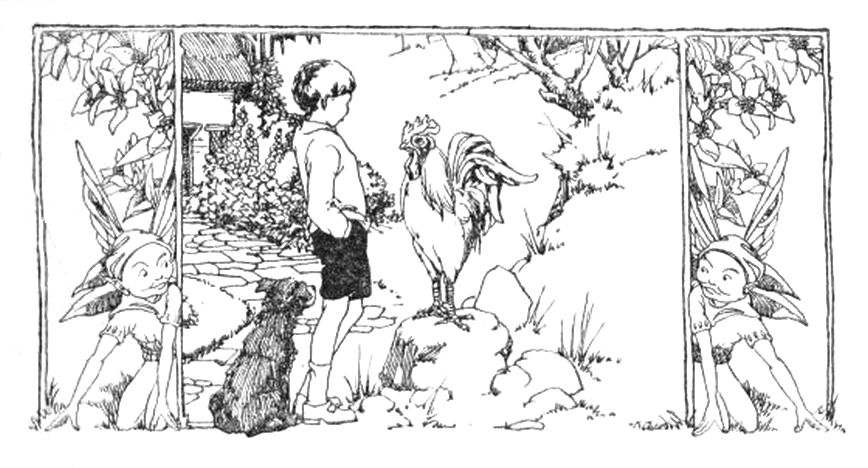

MORE ADVENTURES 89

Alexander could really talk, for barking is talking. George learns more about the little house. The golden weathercock guides them on their way. Everything and everybody can talk. This way to Once-upon-a-Time!

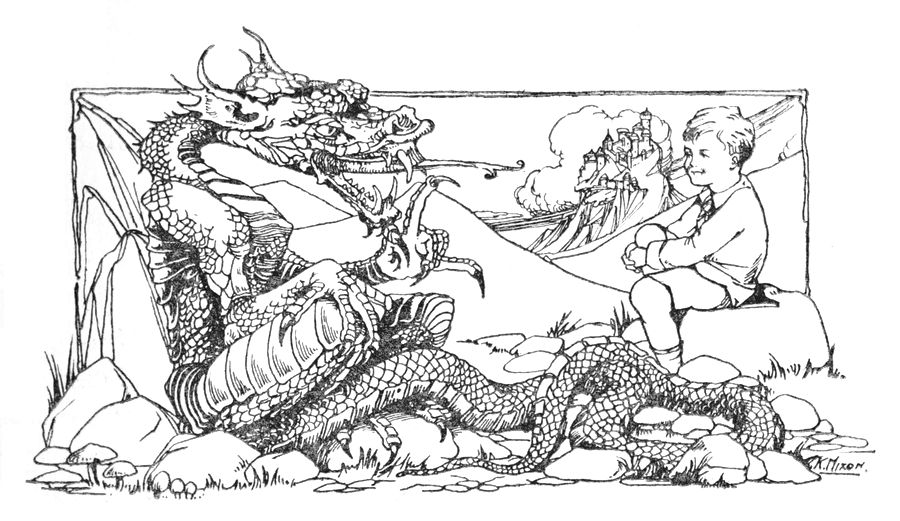

A NICE DRAGON 99

All about the wonders in this strange country. "She lives not far from here." Oh, it was ever so much bigger than one expected! A game at 'catch-my-tail.' The dragon who went to look for his fortune. George is told that he is not real. A ride on the dragon's back.

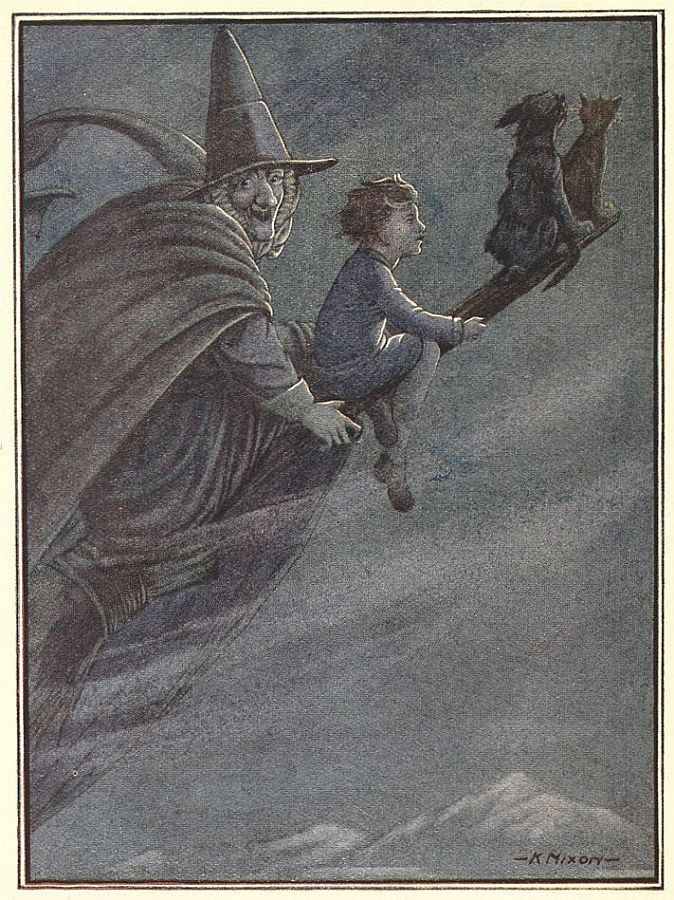

THE WITCH 113

The witch's kitchen. What a witch really looks like. Her curious smile. Wonders will never cease! What happened when the kettle boiled. "Will you ride on your catoplane?" George guesses again. It is all very puzzling.

THE HIGH MOUNTAINS 121

The tower which came to life. "Who's 'Him,' please?" How witches can read your thoughts. Why the giant was so sad. They fly toward the glowing mountains, and George sings a song.

TOM TIDDLER'S GROUND 129

The funny little man who told George all about it. "Ask for what you want." The wonderful meal. Picking up gold and silver. Tom Tiddler's sack. Alexander is George's best friend after all. George's fortune grows heavier and heavier, then lighter and lighter. The story of the golden sausage.

OVER THE HILLS AND FAR AWAY 143

The path which was like the letter S. At the top of the mountain. "Where does that music come from?" The little weathercock again. Home once more. What George found in his sack. Never throw your fortune away!

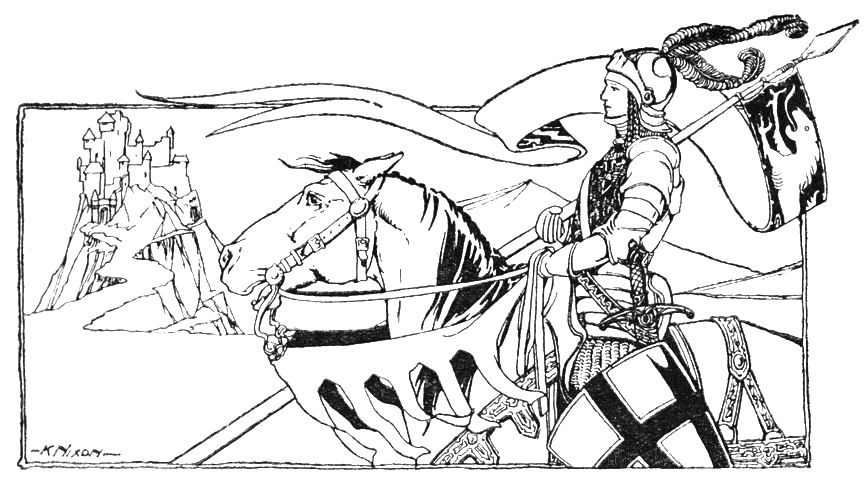

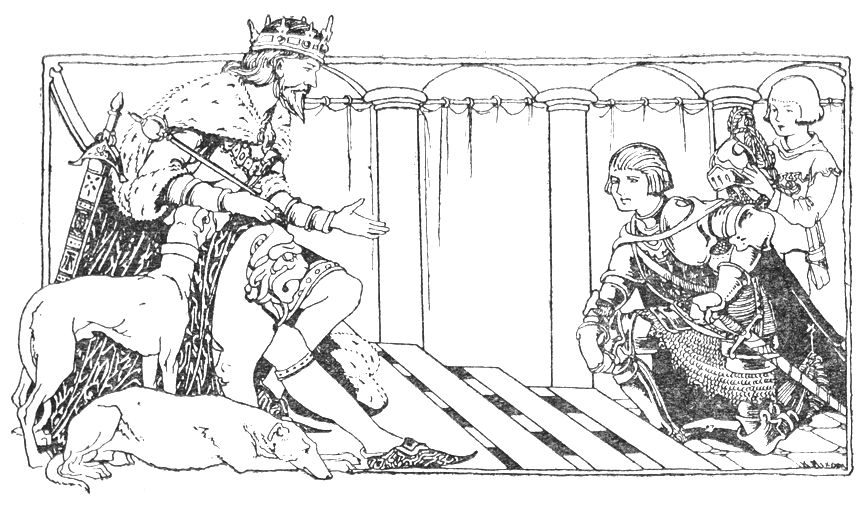

SIR TRISTRAM 153

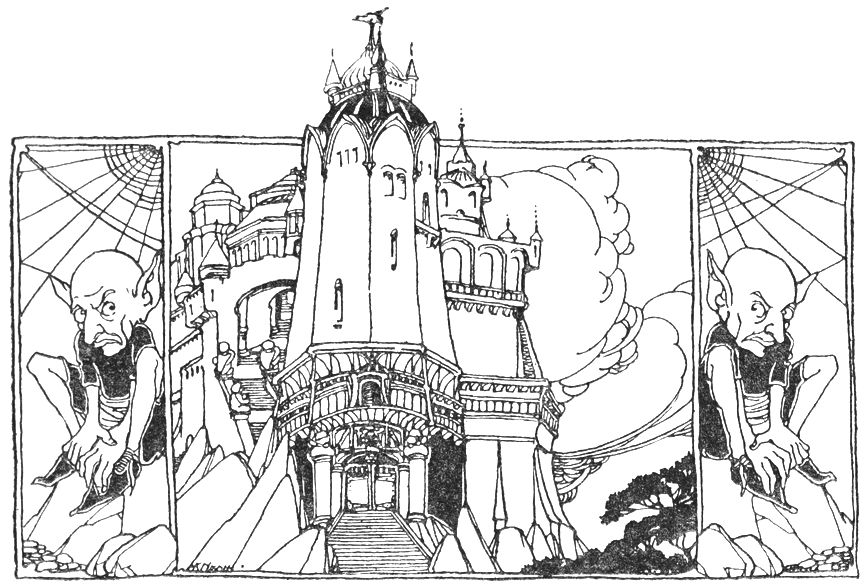

Topsy-turvy thoughts. Fancy a giant with an umbrella! George finds a new suit, and Alexander disappears. To the Castle of the Thousand Towers. The knight who was bound on a quest. They arrive at the castle.

AT COURT 163

About the wonders they saw in the castle. "The King bids you welcome." George becomes a squire. They see the King. Why he was so lonely and sad. What happened to the beautiful Princess Fortunata.

THE QUEST BEGINS 173

The quest to free the enchanted princess. "The weathercock knows the way." They lose their way in the great forest. The mysterious voices in the air, and how George heard about the magician's castle. The greatest adventure of all.

THE GIANT AGAIN 181

On the shores of the black lake. The giant appears again. How they came safely across the lake. The giant begins another story. The prince and his bicycle.

THE ARRIVAL AT THE CASTLE 189

The castle on the glass hill. 'Whizz' once more! "Don't forget to ask for what you want!" The terrible guardians of the gate and how they were utterly vanquished. "Don't forget the password!"

WHAT THE WEATHERCOCK SAID 195

How George learned the password which was a magic charm. "Nobody but you may hear it." How Sir Tristram and the dragon fought, but it was not anything to bother about. George fares on his quest alone.

PRINCESS FORTUNATA 203

What happened to George in the magician's castle. A story which is like a patchwork counterpane. How difficult it was to remember the charm! Alexander barks just in time. The Chinese box-trick. The Princess Fortunata! "The magician is coming!"

ANOTHER PARTY 211

What had become of everybody? The dream-music again. The little house changes. "George is home at last!" The party and supper which George had never heard about before. How each of the guests gave him a present, and the beautiful Queen gave him the best of all. "Of course, you've guessed it, too!"

BACK TO THE WORLD 223

Alexander's bark again. How George and the doctor talked about Fairyland. What they all said about George's adventures. How Mother has a little house in the wood, too, and why she goes there. How George began to understand why his fortune lay right under his very nose.

WHAT THE FAIRIES THOUGHT 235

How the old frog actually laughed! Why George Henry was a wonder-child after all, and why Puck was delighted.

PAGE

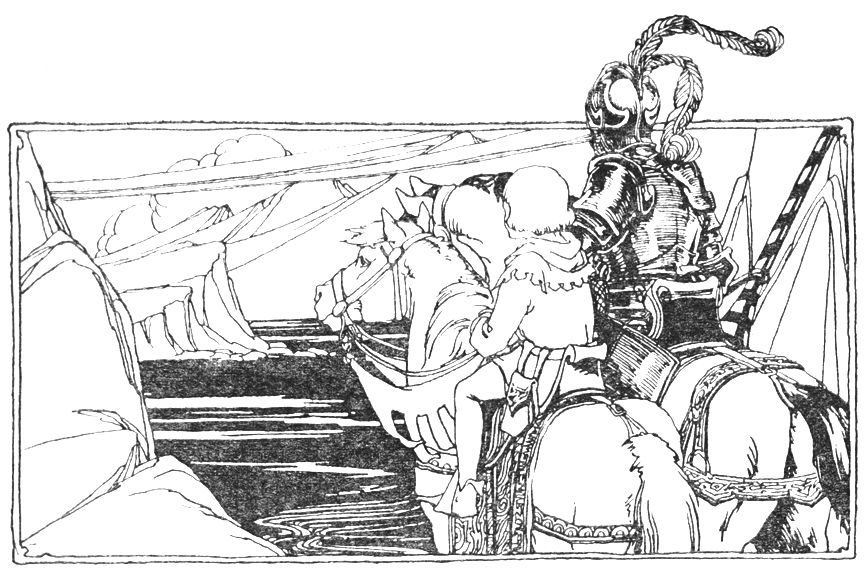

"LOOK, THERE'S THE CASTLE!" SAID THE KNIGHT,

POINTING STRAIGHT IN FRONT OF HIM Frontispiece

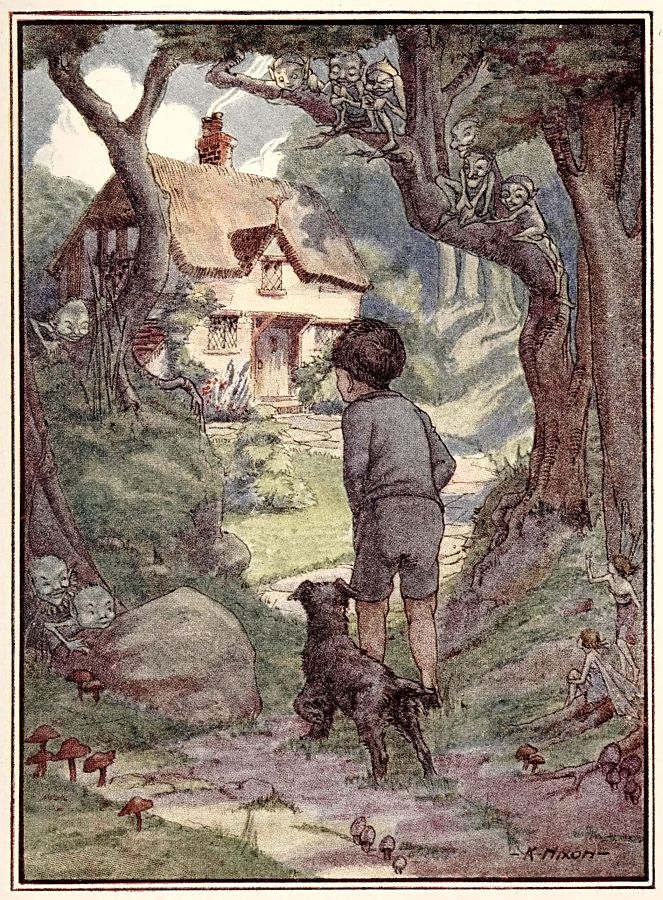

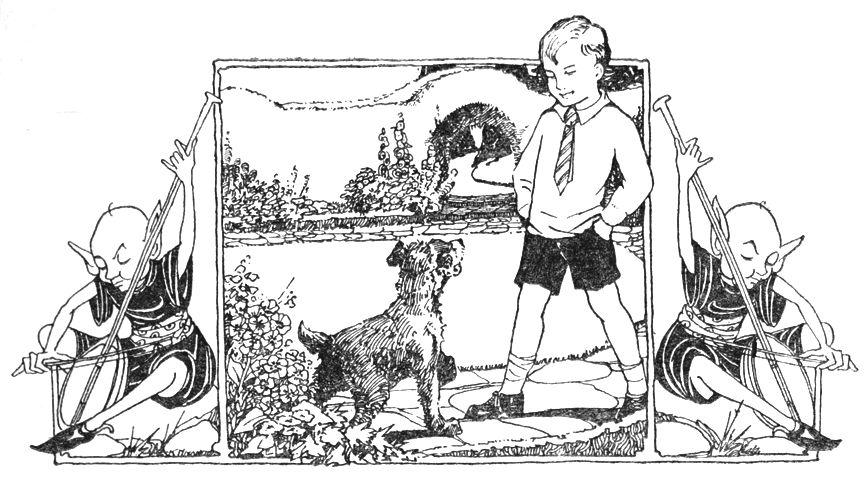

THERE STOOD A DELIGHTFUL LITTLE HOUSE WITH

SMOKE CURLING UP FROM ITS CHIMNEYS 70

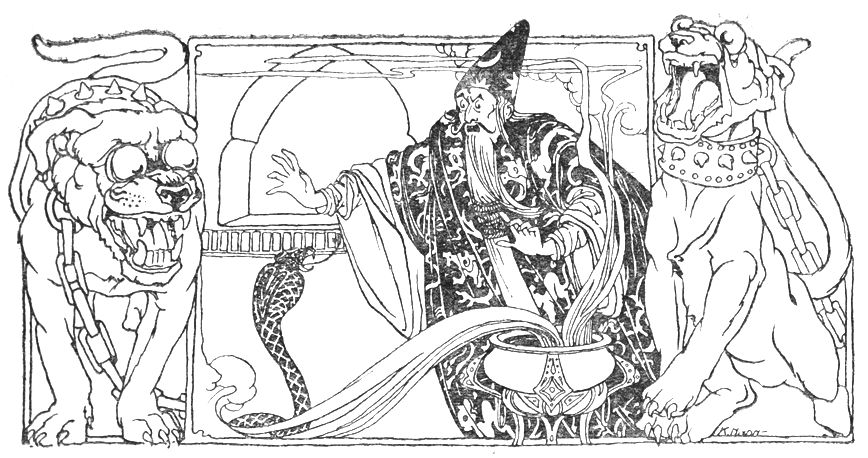

THE LIGHT GREW BRIGHTER AND BRIGHTER 122

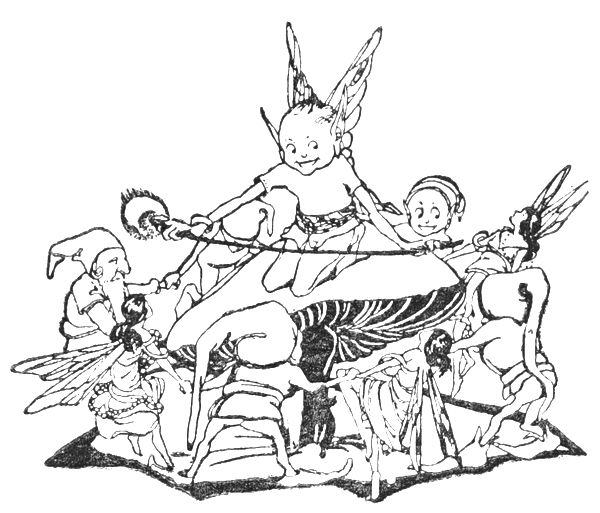

AROUND HIM WERE HUNDREDS AND HUNDREDS OF TINY FIGURES 220

THIS is a true story.

It all happened through George Henry not believing in the fairies, just as some boys but very few girls would do.

Boys believe in Red Indians and pirates, and think fairies are all stuff and nonsense; but they are quite wrong, for Puck can turn himself into anybody or anything he chooses. So if one day when you are ploughing the foaming main you sight a pirate ship flying the skull and crossbones at the masthead, it may not be a pirate at all, but only Puck himself.

Beware! If he catches you he will make you walk the fairy plank, and you will fall off it[Pg 16] splash! right into Fairyland, and find yourself turned into a cross old frog or something quite as disagreeable.

This story should be read aloud. You should seat yourselves in a ring—that will please the fairies—and look happy, even if you aren't as happy as you might be. Sour looks curdle cream and stories as well.

"What!" you say. "Dragons and witches and giants! Do you expect us to believe in them?"

Well, why not? Do you only believe in what you have seen? All the best books are full of wonders like these, and everything wonderful must be true.

So, once again, this is a true story.

Now turn to the next page and begin!

George Arrives

GEORGE HENRY was born under a lucky star, which means that a star laughed when he came into the world. This happens to very, very few of us; perhaps it is because we are born naughty and ready to be stood in the corner at once.

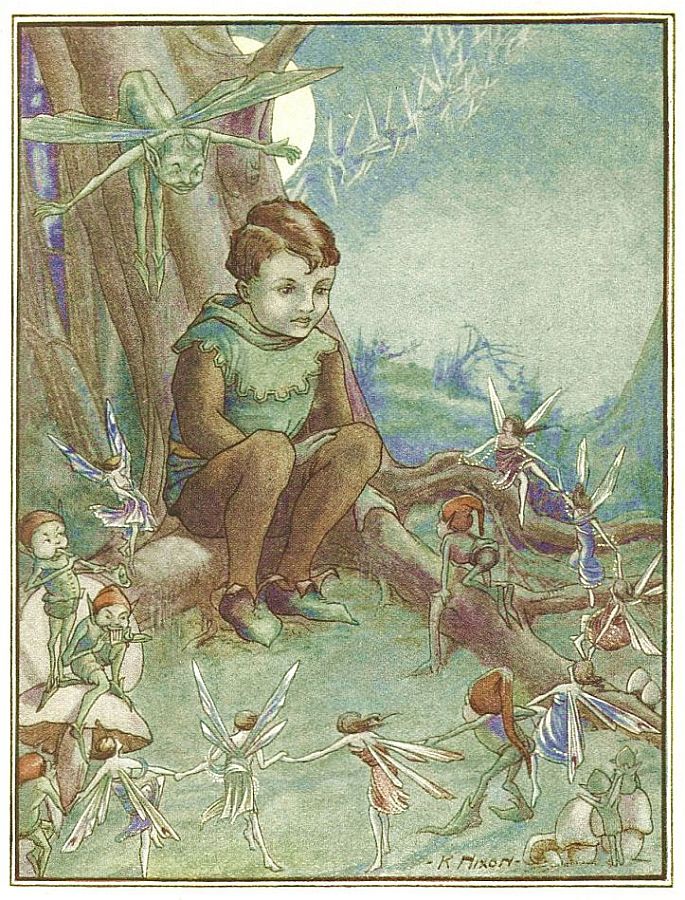

The fairies knew all about George Henry, however, and were delighted, for he was a darling boy. Puck brought them the news wrapped up in a leaf and packed inside a nutshell in order to keep it dry.

Of course you have heard of Puck. He is the little fairy who often plays mischievous tricks upon people; but if children behave nicely he is always ready to be their friend.

Santa Claus often pays him a visit about Christmas-time in order to find out if any children have not been as good as gold during the past year. Then the naughty children find their stockings empty on Christmas morning, and wish and wish—too late—that they had thought in time of what Father and Mother had told them.

Well, the fairies danced that night in the greenwood to the music of the cricket, the grasshopper, and the frog. Puck told them all about George Henry and what a very fine boy he was going to be.

George's father and mother thought so too, and Nurse said that he was the finest child she had ever seen. Nurses always know.

The birds and animals soon heard the news too, and there was such a chattering, jabbering, twittering, squeaking, and I really don't know how to tell you what other curious noises in the wood that night.

This 'wonder-child,' as the fairies called him, was named George Henry—'George' after his grandfather, who gave him a large silver drinking-mug as a christening present, and 'Henry' after his father. His mother would have liked to add 'Alexander' as a third name,[Pg 19] but it was given, after all, to a new black, woolly puppy which came into the house about this time; so that was all right. It is a great pity to waste fine names like Alexander.

George Henry and Alexander grew up together and were great friends. Alexander learned to walk long before his little playmate, who used to toddle along holding on to the dog's tail, and very often falling over on top of him when his legs grew tired.

As soon as he got past his toddle-days he loved to walk about everywhere and see everything.

The world was full of the most wonderful things; there was a pigsty in which lived a family of little pigs with curly tails. They used to squeak "Good-morning" to him every time he passed by.

He loved their curly tails, and often tried to make Alexander's tail like theirs, but it was of no use. It either stood straight up on end or else disappeared between his legs.

It was fine, too, to see the geese marching along like soldiers with the old gander at their head; to watch the old hen fussing and clucking after her little fluffy chicks, who would never come home when they were told—"Like[Pg 20] naughty little boys, you know," said Nurse.

It would take hours to tell you all the things Alexander and he saw together—the animals, the birds, the trees, the flowers; and they all loved him. But he never saw the fairies—though they often waved their little hands to him; and Puck sometimes rode on Alexander's back through the woods and led them to all the prettiest spots—but George never knew.

By and by, when they had grown up a little more, and George was in sailor trousers, while Alexander had a great big bark which quite made you jump the first time you heard it, Father and Mother began to wonder what George would be when he became a man.

He loved playing at soldiers, and had boxes and boxes full of them which Grandfather and Grandmother, uncles and aunts, and other kind people gave him from time to time. He played with them on the nursery floor, up and down stairs until the housemaid, Anne, fell over them, on his bed when he ought to have been asleep, until Father said: "Ah, the boy will be a general and win great battles when he grows up!"

"No!" answered Mother. "George is born for something better than that."

He knew all about everything in the shop windows, better than even the people to whom the shops belonged.

"He will be a great merchant!" said his grandfather.

"Pooh!" answered Mother. "Buying and selling? My little George was not born for that."

He began to use paper and pencil, and then a paint-box.

"Ah!" said the aunt who had given him all these things. "George will be a great artist who will draw and paint most wonderful pictures."

"Rubbish!" replied Mother. "George was born to do something great. He can always draw pictures to amuse himself."

Then he learned to write, and wrote the most wonderful stories which no one except himself could understand.

"He will be a great writer and write stories which everybody will read," said his grandmother.

"I never heard such nonsense!" cried his mother, quite vexed. "Don't I tell you that he[Pg 22] is going to do great things? Anybody can write stories; besides, he might sit up late at night and catch colds and I don't know what else if he began writing stories!"

Puck was delighted to hear them all guessing in this way, and laughed until he fell off the top of a big sunflower on which he was sitting.

"Oh, dear!" he cried. "How funny these big people are!" And he flew away into the wood to tell the fairies all about it.

They laughed and laughed for days and days, and were never tired of hearing Puck talk like Grandfather, Father, Mother, and Aunt.

Even the old bull-frog in the large pond, right in the middle of the darkest part of the wood, croaked "Ker-ek!" which was his way of laughing. He always had a cold, poor fellow, because his feet were never, never dry, and nobody ever thinks of giving frogs medicine. Perhaps they have neither nurses nor aunts.

And so the days and months went by, and presently George was big enough to go to school. It was quite a nice school, so Puck said, for he went there when he had time. Puck liked to listen to the fairy stories best of all,[Pg 23] and often sat on the teacher's shoulder and whispered in her ear. You would have been surprised and delighted to hear what splendid stories she told the children on those days, and she could never imagine how they came into her head.

Now, it is a very sad thing to have to tell you, but Puck soon found out that George did not believe that there were any fairies, nor—worse still—that there ever had been any.

One day he actually fell asleep when the very best story of all was being told! Puck didn't know what was to be done, and the fairies couldn't help him, for they had never heard of a boy like this before. "Dear me!" they said. "If there were no fairies how could there be any fairy stories? How stupid of little George not to believe in us! We believe in him, and he is only a boy and not a fairy at all."

So Puck set to work to think what to do, and went wandering through the woods, asking all the birds, all the beasts, and even the insects if they knew what to do with a boy called George who didn't believe in the fairies. None of them were able to help him. An old horned beetle[Pg 24] said, "I should pinch him!" but Puck didn't think that pinching was of much use.

When George went to bed, Puck used to sit on his pillow and tell him the most beautiful dreams, but George forgot all about them when he woke up. What can one do with a boy like that?

Nurse, however, just nodded her head wisely and said: "Wait and see!" There are thousands of nurses saying the same thing all over the world. They just know what will happen later on, and that is all. They never tell anyone else. If they do they are not real nurses, and should be given a month's notice.

George's nurse was what people called a 'comfortable' person. She was big and round, and her shoes creaked just now and again—quite a lady-like creak. She did not often smile, but when she did you felt sure the sun was shining and that the world was a jolly place to live in. Nurses—real nurses—know everything; very likely they have been taught by the fairies, but if you asked your nurse this question she would never tell you. Oh no!

Nurse always spoke of Alexander as "that black imp," but he knew how to coax a piece of biscuit from her whenever he wished. He[Pg 25] used to sit down on the nursery hearth-rug with his head on one side, thump gently with his tail on the floor, and bark very gently, "Wuff! Wuff!" without stopping, for ever so long.

It must be a grand thing to be a dog like Alexander whenever one wants a biscuit.

George was very busy just now, for he had made up his mind to be an aviator. An aviator is a man who flies up in the air on a machine which looks something like a large bird, and makes a noise like ever so many cats quarrelling. It flies straight up, and then before you can say "Knife!" it is out of sight. There are no tunnels or stations, no tickets such as you have on the railway. You just go straight ahead until you get there.

No wonder George didn't think about the fairies when his head was full of such wonderful things.

But Father said: "Time enough to fly when you are grown up."

Mother said: "An aviator? No, George, darling! You can come for a ride in the carriage with me this afternoon."

And Nurse said—of course, the same as before.

And so the months and the years went by;[Pg 26] George grew bigger, Alexander grew fatter, Nurse grew more and more comfortable, and Puck grew crosser and crosser. At last, one day, everybody woke up and said: "George Henry is eight years old to-morrow!"

George Grows Up

IT was not long before everybody knew all about it. George was going to have a party! Not an ordinary party, but a splendid one. There were invitations for all George's friends, both boys and girls; for Grandfather, Grandmother, uncles, aunts, and all kinds of grown-ups who could help to hand round the tea and cakes and let off fireworks when it grew dark.

George was quite ready to have the fireworks first thing in the morning as soon as he woke up; but Father said, "No!" Mother said,[Pg 30] "No!" and Nurse said nothing, but just looked. Nurses don't like fireworks, though they sometimes pretend they do.

Everybody—except Alexander—must have been getting ready for this birthday for weeks and weeks, for when George woke up a little earlier than usual on the great day there was quite a stir and bustle in the house. The postman could hardly carry his bag along the path up to the front door. It was packed full of presents.

Alexander had a big red silk bow fastened round his neck, and nearly fell all the way downstairs through twisting his head round to try and bite it off. Even Nurse, for once, almost ran, she was in such a hurry.

It is a wonderful thing to have a birthday if you have enough kind uncles and aunts to help. Uncles must be strong enough to carry you on their shoulders like a never-tiring horse, then to change into bears which you can shoot at, and, almost before they have finished dying under the sofa, they must be ready to change into anything else you may want.

Aunts are best when they smile all the time and bring out sweets and chocolates from some hidden part of their dresses, like conjurers, just[Pg 31] when you are tired and want to rest for a minute. Alexander liked aunts, and was always ready to beg for biscuits even when he met one of them in the middle of the street or in a shop. Uncles were all right, but rather tiring. Dogs don't always want to play games.

Well, the number of presents was perfectly delightful, and everybody had sent exactly what George wanted. But in the middle of breakfast he looked up suddenly and said: "It's Alexander's birthday too. Hasn't he got any presents?"

"What?" said Father, turning quite red in the face and forgetting that he was holding a piece of bacon on the end of his fork.

"Dear me!" said Mother, looking as if she were going to cry. "Oh, where's Nurse?"

Nurse appeared in the room at once, and when she heard that it was Alexander's birthday, do you think that she said "What?" or "Dear me?" Not at all.

She just went to the door and called: "Alex—ander!"

Alexander arrived with a rush and a bang, looking as if nothing in the world would ever surprise him.

"Alexander," said Father solemnly, "I have great pleasure in telling you that this is your[Pg 32] birthday. I wish you many happy returns of the day!"

"Wuff!" replied Alexander, wagging his tail, and looking at Father as much as to say: "Don't keep me waiting any longer. You know how hungry I am!"

Father smiled, and suddenly in his hand he held a most beautiful silver collar, on which was written Alexander's name. He took off the red bow and put the collar round Alexander's neck. Alexander said nothing, but sat and waited.

Mother wished him 'many happy returns' too, and then—where had she hidden it?—there was a pretty tin of sugary biscuits with 'A' printed on the top.

"Wu—uff!" said Alexander, and wagged his tail so hard that he nearly fell over.

George looked quite pleased. "I'm so glad he wasn't forgotten," he said; "it didn't seem fair for me to get such lots of things, and Alexander nothing at all."

It was soon four o'clock, and the guests began to arrive, first in ones and twos and then in threes and fours.

It was a lovely summer day, and after games in the garden there was a Punch and Judy[Pg 33] which everybody liked, especially Father and the uncles. Alexander sat quite still until Punch's dog appeared, and then he had to be led indoors and shut up, for he grew quite fierce, and was just getting ready to bite Punch's nose off.

Punch without a nose wouldn't be a Punch at all, and then the man who keeps him would never be able to go to parties again. But Alexander never thought about that.

By this time everybody was ready for tea, which was served in a large tent in the garden. On the middle of the table stood a very large cake stuffed full of plums. Nurse had made this with her own hands, and there were no cakes like hers. One could eat two and even three large-sized slices and scarcely feel a little bit uncomfortable afterward.

No one could eat any of this cake, however, until most of the white and brown bread and butter—you were allowed to have jam spread on it—scones, tea cakes, cream cakes, ice cakes, jam puffs, tartlets, and oh! heaps of other things had disappeared. Then Father stood up with a large knife in his right hand, and made a little speech. Everybody clapped their hands and laughed—even the uncles and aunts who had had no tea at all.

George sat in a high chair looking as proud as a king. Kings always look proud, and queens, their wives, look proud too, but in quite a nice way. If you have ever seen them riding by in a carriage drawn by six white horses in gold harness you will understand exactly why you cannot really look proud in a cab with one horse, or in a taxi-cab which flies along with a fizz and a bang. You only just have time to get the eighteenpence ready for the driver. If you were a king you wouldn't ever have to do that.

After the speech George cut the cake and Father helped, so that everybody, grown-ups and all, had a slice.

Then George had to speak. "Thank you very much," he said. "I hope you've enjoyed the party. I know I have, and so has Alexander. Now we're going to have the fireworks!"

It was not dark yet, so there were games and races, followed by a little rest, during which Mother told them stories. Then Uncle William, the funny man of the party, gave an imitation of all the animals in a farmyard, which was even better than the real thing, of a railway train coming out of a tunnel, and, last of all, of Father getting up in the morning.

Father laughed so much at this that Mother[Pg 35] had to pat him very hard on the back for several minutes. Uncle William was not allowed to tell the story of the two cats on the wall, because Alexander did not like cats—even cats which weren't real.

At last it was time for the fireworks, and all the children seated themselves at one end of the garden and waited patiently. Suddenly bang! up went a red star, then a green one; then showers and showers of little green ones. Then bang! bing! bang! fizz! crack! jumped the crackers. Rrrrrrr! whirled the Catherine wheels, slowly at first, then fast, faster, and so fast that they made your eyes quite sore watching them.

Hiss! Whizz! Bang! went a rocket with a tail as long as from here to the end of the next street. Higher and higher it flew, until, all of a sudden, just as you thought it was quite out of sight, it burst, and—ah!—hundreds of little stars lit up the sky and made it look lighter than even the lightest day.

But there was something better to come still. At the end of the shrubbery a light shone faintly and then went out. Then shone more and more lights, until you could see that great big letters as tall as yourself were growing up. And then—all[Pg 36] of a sudden—in a blaze of light there was spelt out for all to see, GEORGE.

Such crackings and bangings, such shouts and cheers from all over the garden you never heard, nor anyone else either.

That was a real surprise.

Just as people were getting ready to put on their coats and say "Thank you very much for your delightful party," another light shone out over the high tree near the garden gate.

"Hullo!" said Father. "Hullo, what's this? A surprise from Uncle William, I expect," and he stood still and watched.

Brighter and brighter grew the light, longer and longer, until it looked like a great tongue of fire. Then it swept along over the trees, under the trees, in and out and round about, until it looked as if thousands of little lanterns were shining everywhere.

"It sounds as if there were music somewhere, quite far off," said Mother. "Well, I don't know what it can be."

Uncle William, who was supposed to know all about it, said that he hadn't done it, but nobody believed him.

Little by little the lights died out, and then it was time to go home to bed.

George was quite sleepy, and was very glad to find his head resting on a soft pillow. After he had said his prayers and said "Good-night," he called out to Nurse: "Do you know who made those jolly little lights, right at the end of the fireworks?"

Nurse stood silent for a moment: "Perhaps I do; perhaps I don't," she replied.

"Oh," said George, "tell me, then!"

"Good-night, Master George." Out went the light, and if George hadn't been so sleepy and tired he might have found out all about it then and there; but that would have meant that all kinds of things which were just going to happen wouldn't have happened at all, which would have been a pity.

Puck sat cross-legged on an old toadstool, and the fairies danced all round him in their magic ring.

"It was a jolly party!" he said to the old frog. "You ought to have been there."

"Ker-ek!" replied the frog. "My throat was rather sore to-night, so of course I could not go. I hear there were fireworks."

All the fairies stopped dancing and burst out laughing when they heard him say this.

"What are you laughing at?" he croaked.

Puck jumped off his stool and turned head over heels.

"Tell him! Tell him!" they all cried out.

"Well," said Puck, "we were all there. The fairy music band played; the fire-flies and glow-worms made beautiful fireworks, more beautiful than the grown-ups had bought—and no one knows who did it. What fun!"

"Ugh!" said the frog. "I don't see anything to laugh at."

"Don't you?" said Puck. "Well, wait until we have our party and invite George."

"He won't come," croaked the frog.

"Won't he?" replied Puck. "Won't he?"

Midsummer Eve

IN a few days' time it would be Midsummer Eve, and then the little fairies have a dance and supper all to themselves. Very few people have ever been there, and even fewer know anything at all about it. Only the very best people receive invitations, and, of course, there are never very many of the best people in the world.

It is very hard indeed to be good, but—oh dear!—to be best! Why, it means being good, and going on being good, until you are so good that Mother thinks something must be the matter with you and sends for the doctor.

Anyway, the fairies sent George an invitation, but he didn't understand what it meant, for it was written on an oak leaf which Puck blew in through the bedroom window. George thought it was only a common leaf and never picked it up.

"Well, has George answered his invitation yet?" said the old frog to Puck a few days before the dance.

"No," replied Puck, "he hasn't, but he's coming."

"Coming, indeed!" croaked the frog, who had just caught a worse cold than ever. "Well, I'll believe it when I see him, and not before."

"All right," said Puck. "You'd better go home, or else you won't be able to come to the party with that cold of yours."

There was such a bustling, a running about, a flying here and a flying there in the wood all day and all night getting ready for Midsummer Eve. Such a brushing and combing, such a sewing and darning, polishing and scrubbing, and I don't know what else! Such a baking and brewing, cooking, stewing, and such nice smells! Puck carried bits of these away in his pocket, and George had the most delightful[Pg 43] dreams of all the things he liked best to eat and drink.

Nurse smiled when he told her, and Alexander listened with his head a little on one side, hoping to hear the word 'biscuit' or 'bone.' His idea of a really good party was a pile of bones and biscuits, with leave to eat them on the drawing-room carpet. This is just as good fun as waiting outside on the stairs for the jellies and creams when there is a dinner-party at your house.

George had already forgotten about aeroplanes, and was very proud of being in trousers. When he first wore them he could not help looking down almost every minute to see if they were still there. The worst of wearing trousers is that you have to be so careful. Dogs like Alexander will jump and bump against them, leaving dirty paw-marks, just when you are not looking. Directly one begins to grow up there are really such a number of things one must think about.

George used to stand with his legs wide apart and his hands in his pockets like Father, until Nurse sewed the pockets up tight one night when he was fast asleep. Trousers without pockets are like jam tarts without jam.

George said nothing when he found it out, but[Pg 44] in the garden after breakfast he remarked to Alexander: "When I grow up—really grow up—I am going to have pockets all over me, just as many as ever you can imagine. There will be so many that no one will ever be able to sew them up again."

Alexander nodded. After all, he might be able to keep his bones in a suit with as many pockets as that!

Midsummer Eve came at last. Everything was ready in the wood; even the old frog's cold was better, though he was still rather hoarse. The fairy ring was as smooth as velvet, and the fairy band had learned quite a number of new tunes.

Puck was as busy as he could be, and whenever there was a moment to spare he brought another piece of moss for the seat which he had been making for George. It was right in the middle of the wood in a little open space with high trees all round it. Whenever the wind came the trees rustled softly, and it sounded just as if they were putting their heads together and whispering secrets. Most of these trees were very old; so old that they had grown quite bent, and their long, twisted boughs hung down almost to the ground.

On Midsummer Eve the moon always shines brightly, and lights up the fairy ring with a soft, silvery light. No one knows whether Puck asks her to do it, but if you will look out of your window—if you can wake up at the right moment—you will see for yourself that it is quite true, for so many of the best things always happen while we are fast asleep in bed.

George went to bed as usual. Alexander flopped down on the mat outside the door and curled himself up. One by one the lights in the house went out, and soon everybody was fast asleep. It was as still as still can be.

Far, far off sounded the first notes of the fairy music. Alexander pricked up one ear for a second, then sighed and fell fast asleep again.

George turned over in his bed and began to snore. Puck flew in through the half-open window and rested for a moment on his pillow.

"It's all ready, George," he whispered. "We're only waiting for you!"

George snored a little louder.

"George!" cried Puck, "George, come along! Don't be late!"

George was dreaming. He was dreaming that he was in school saying the multiplication table, twice times, three times, and some of four[Pg 46] times. He actually wasn't thinking about the fairies at all!

Puck sat for a moment thinking what he should do; then he flew out through the window and back to the wood.

The multiplication table, indeed! No one ever thinks of such things on Midsummer Eve. It is a time to dream of dancing, music, light, laughter, the wind in the trees, the tinkle, tinkle of water in the little brooks, the song of birds—they are all awake then—of almost anything else, but not twice times two.

The fairies were just beginning to dance when Puck flew into the middle of the ring, and he looked so angry that they all stopped, wondering what could have happened.

He could say nothing at first but "twice times four is ten," which is nonsense, but he had never learned his tables and never wanted to. He said this over and over again, just as if it were a rhyme, and they all listened, though they did not understand a bit what it meant.

"Oh, ho!" said the old frog, who was sitting there puffing himself out as if he were trying to turn himself into a toy balloon. "Oh, ho! I see what it is. George won't come after all. I told you so. Oh, ho! Oh, ho!"

"For shame!" all the fairies cried out. "For shame! Nasty old thing! You're quite glad he isn't coming."

Puck sat with his head in his hands, thinking and whispering to himself, "Three times four are seven," which was worse than ever.

The fairies felt so sorry for him. They all came and sat round him in a ring with their little heads in their hands. They did not know why he was doing this, but they did it to cheer him up. The old frog sat puffing, just as if some one had wound him up like a clockwork toy and he wasn't able to stop.

After a long time Puck looked up and said: "Well, it's no use waiting. He won't come to-night."

The old frog was so pleased when he heard this that he opened his mouth to say "I told you so," but he had puffed himself out to such a size that he fell over backward suddenly into a pool with a great splash, and never spoke another word for the rest of the evening.

"No, he won't come," said Puck, "it's no use waiting. I always thought he would learn to believe in us after a time, but he won't, he won't!" And he spun himself round on one[Pg 48] leg like lightning a hundred times without stopping. He was really angry!

The fairies all spun themselves round on one leg too, but this made them so dizzy that they fell over one another in heaps, and for a few minutes they really didn't know whether they were on their heads or their heels. At last they were all right side up again, wondering what it was all about.

"Let's go on with the dance now!" cried Puck. "I'll tell you all about it to-morrow."

The fairy music began again; the fairies danced round the ring, and all the animals in the wood came out to watch them. The moon looked on with a smile; she was always very fond of the fairies, and never minded shining a little longer than usual if the fairies wanted to go on dancing.

At midnight they were ready for supper. First of all they had—but wait a bit!—it is not time to tell you about that yet, with George snoring away in bed, and saying his tables over and over to himself.

After supper they danced again, and acted a little play in which they pretended to be grown-up people at a party.

One fairy pretended to be Alexander, and barked "Wuff! Wuff!" so like him that all the rabbits ran back into their holes in a fright. It was delightful to hear the tinkle of the fairy laughter.

If you strike a glass very, very softly with a spoon several times, that sounds something like a fairy laughing—but not quite.

Puck had forgotten about George now, and was enjoying himself as much as the rest of them. He pretended that he was an aeroplane, and flew round and round until he looked as if he would fly away for good.

Then he turned head over heels ever so many times until you could hardly see him. Then he pretended to be the old frog, "Oh, ho! Oh, ho!" and puffed himself out and coughed until the fairies nearly died of laughing.

By and by the moon began to disappear behind a cloud. This was her polite way of saying that it was time for her to go to bed, because the sun was just getting up.

The party was at an end; and soon over the top of the hill peeped the sun, very red in the face, ready to begin his day's work.

Dream-Music

WHETHER it was the cakes or the fireworks, no one ever knew. Father said that it must have been the cakes. Nurse thought it was the fireworks. The doctor, who came in a little motor-car with just room for himself inside, shook his head and looked very solemn.

George was not well and was kept in bed. The doctor sent a large bottle of medicine, and Nurse shook the bottle very hard before giving George two large tablespoonfuls. Alexander sat at the end of the bed and looked on. Perhaps he thought he ought to[Pg 54] have some medicine too, for he was always ready to taste anything, and even a tin of boot polish didn't seem to disagree with him. There were very few things that he hadn't tasted.

The doctor came every morning for four days, and every morning his little motor puff-puffed outside the garden gate whilst he went upstairs into the bedroom where George was, and said: "Well, and how are we this morning? A little better, eh?"

But George always said that he felt a little worse, and wanted to get up and go out for a walk with Alexander. He was cross with everybody, and at last Mother thought he must be really ill.

She sat by his bed and read stories to him; sometimes he listened, and sometimes he just kicked his legs about in bed and said: "Oh, do let me get up. I hate being in bed."

"You must be good, George dear," said Mother, "or else you will never get well."

It was no good. George wouldn't even listen to Nurse now, so it was not a bit of use talking.

He wouldn't take his medicine; he wouldn't lie quiet. He did everything he ought not to do. Even Alexander looked as if he would[Pg 55] like to cry, and never once wagged his tail. This showed how sorry he felt for himself and for everybody else.

At last George was so tired that, as it was growing dark, he fell asleep. Nurse sat by the side of his bed with a large pair of spectacles on, knitting a pair of stockings.

As fast as she knitted stockings for George he wore them out, but she didn't seem to mind. What the boys do who haven't got nurses it is difficult to say. Think of all the stockings there must be in the world with holes in their heels and toes and knees! It was quite quiet. Nurse sat as still as still could be; if her fingers hadn't been moving all the time you would have thought she was fast asleep.

It grew darker and darker, until at last the moon came out from behind a cloud and shone through the window. It was just the kind of night on which the fairies love to be dancing in the wood. Perhaps they were.

"What a splendid sleep you've had, darling," said Mother, as she kissed George next morning.

George sat up in bed and rubbed his eyes. "I've had such a dream!" he began.

"Won't you tell me all about it?" asked Mother.

George thought for a long time, then shook his head. "It's all gone again," he said. "I can only just remember that I went for a long walk with Alexander, and we came to such a wonderful place. I think I met Nurse there, but she looked quite different ... and yet she was just the same."

Nurse smiled.

"Were you really there?" asked George.

"Perhaps," she replied. "Now it's time for your medicine."

By the time he had finished his medicine George had forgotten about the dream, but he kept remembering it in bits all day long.

Alexander looked delighted when George was allowed to get up and come into the garden. Perhaps he knew all about the dream, for he would often stop when he was digging up a bone, and look as if he were trying to remember something.

Dogs have splendid dreams sometimes. When they give short little barks in their sleep they must be chasing cats. But what do cats dream about?

The doctor did not look at all solemn to-day.[Pg 57] He sat in the garden and talked to George about motor-cars and aeroplanes. But George was all the time trying to remember his dream, and told the doctor little bits of it whenever he remembered.

"Do you believe in fairies?" George asked the doctor suddenly.

"Fairies?" said the doctor. "Well, you believe in them, don't you?"

"I don't know," replied George. "I think my dream last night was about fairies, but they weren't very like the fairies in the books I read. Is there a real Fairyland?"

"Well, you see," replied the doctor, looking very solemn again, "you really ought to go there and find out."

"But how can I find out," asked George, "if I don't know whether there is a Fairyland or not? How can I find the way there?"

The doctor scratched his head. "Well, I expect Nurse or Mother will tell you all about it," he said.

"Nurse always answers, 'Perhaps there is and perhaps there isn't.' I don't believe any of you really know at all," cried George.

The doctor shook his head, looked as if he were going to say something, then smiled and[Pg 58] said: "Perhaps!—that's just what we've all got to find out about a great many things, George. If you really want to find the way there, I expect you will. Only you must wish hard, as hard as ever you can!" and with a laugh he went down the garden path, stepped into his motor, and puff-puffed away.

"I don't believe there are any fairies," said George, with a stamp of his foot. "It's just silly nonsense, and they only say that there are fairies to tease me."

Puck was sitting on a toadstool watching the little fairies, who were having a flying race. They flew round and round and up and down, and the colours of their little wings were as beautiful as the most beautiful rainbow. Maybe the rainbow is made out of fairies' wings.

When they were tired they all fluttered down to the ground again and sat down on the grass in a ring. They love to sit like this, because most of the good games are played when one sits round in a ring. The fairies are never tired of playing games. Even their work is play to them, and so they never need to go to school.

No one ever heard of a fairy schoolmaster or[Pg 59] schoolmistress. If there were such people, they would be playing all the time, and so they couldn't possibly be teachers.

They had forgotten all about George, for they really believed by now that there was not a boy of that name at all. When grown-up people forget about the fairies, is it because they are getting old and thinking about what they should eat and drink, and what clothes they should wear? The fairies know that grown-ups do these silly things, and don't mind, but children ought to know better. The fairies were not playing a game just then. They were listening to Puck, who was telling them a story. It is hard to guess what the story was about, for the fairies do not have fairy stories. What seems so wonderful to us is only what happens to them every day, and so whoever tells a story in Fairyland must think of something quite different.

They enjoyed the story very much, for they laughed and clapped their hands, and even the old frog forgot his cold.

"To-night! To-night!" they all cried when Puck had finished, and then they all danced round and round so fast that it would have hurt your eyes to look at them.

The moon shone more brightly than ever that night. The sky was covered with bright, twinkling stars, and a soft, warm breeze rustled through the tops of the trees in the wood.

George would have loved to go for a walk, but he was tucked up safely in bed, and Alexander was lying on the mat outside his door. Nurse had left him alone for some time, and he couldn't get to sleep. He wanted to dream again and go back to that wonderful country of which he remembered so little.

He tossed about on his pillow, wishing that he were outside in the garden or anywhere except in bed. He could hear the old clock outside on the landing, tick, tock, tick, tock, and now and again Alexander gave a little bark which showed that he was fast asleep and dreaming.

Suddenly he heard another sound. It seemed to be far off, but little by little it sounded nearer and nearer.

"It's just as if somebody were blowing little trumpets," thought George to himself. "I wonder where it can be?"

The sound of the music floated in the air, died away, and then, more sweetly than ever, echoed and echoed until it seemed as if it might indeed be fairy music.

"I must get up and see what it is," said George. "It might be soldiers, though they don't seem to have a drum."

He jumped quickly out of bed and went to the window. There was nothing to be seen, not even a shadow on the lawn.

"That's very queer," thought George. "I wonder that Alexander hasn't heard it."

After waiting for a few minutes he got back into bed, and scarcely had he laid his head on the pillow when far, far away sounded the fairy music.

"Lovely! Lovely!" murmured George. "It must come from that country I dreamed about last night."

The Land of Dreams

IT was still, so still in the wood that you could have heard a pin drop. One doesn't usually drop pins in a wood, but on the floor, or on a chair, or somewhere else where they are sure to run into you just when you are not expecting anything of the kind.

There was not a breath of wind; the trees, standing in rows like giant sentinels, seemed to be waiting for somebody. Who could it be?

A lovely path of soft green moss ran through this wood from one end of it to the other. Far away one could see a little patch of blue. This was the sky. The trees were so high[Pg 66] that they formed a roof overhead and shut out nearly all the light.

By and by there was a joyful bark, and dashing through the wood came a black dog with his tail waving behind him. It was Alexander! He was enjoying himself.

George came hurrying along after him. Though he had been running for quite a long time he didn't seem to be a little bit tired. His cheeks were rosy, his eyes were bright, and he sang aloud for joy. He was so glad to be out with Alexander once more.

"Wait for me, Alexander!" he cried. "Wait for me. Don't be in such a hurry!"

Alexander came bounding toward him, and after chasing one another in and out of among the trees they threw themselves down on the soft moss to rest for a moment.

"I think I should like to lie here all day," said George. "I don't remember coming to this part of the wood before. I wonder how we got here. Do you know, Alexander?"

"I brought you here, little George," said Alexander—at least, it sounded as if he had said that, and for a moment George thought he had really spoken.

"That would be fun," he thought to himself[Pg 67] as he lay back with his head against the trunk of a tree. "What would they say if I went home and said that Alexander had been talking to me?"

Suddenly, far, far off he heard the music again. It seemed to be calling, calling to him: "Come, little boy, come and dance and play! The sun is shining; the soft wind is blowing. Come and play with us!"

"What nonsense!" said George aloud. "I must be dreaming again. I wonder if the doctor gave me that medicine to make me dream. What was it he said to me about Fairyland?"

"Wish as hard as ever you can!" said Alexander.

George was so startled when he heard Alexander speak for the second time that he fell down backward. Then he sat up slowly and looked at him. The dear black dog was sitting up, looking at George with—yes!—a smile on his face, and wagging his tail gently to and fro.

"Now am I dreaming or not?" said George.

Alexander still smiled and wagged his tail, but he said never a word this time.

"Come on!" cried George, and he ran down the path as hard as ever he could.

He ran and ran until suddenly he found himself right out of the wood and in the midst of a most beautiful meadow. A little stream of clear blue water flowed gently along past banks carpeted with flowers. There must have been hundreds of them, and every one a different colour.

The sun was shining as he had never seen it shine before, and yet he did not feel a bit too hot.

He looked around him, but there was no one to be seen. The only sound was the soft gurgle, gurgle of the stream flowing over the stones. He lay down by the side of it, and hollowing his hands to make a cup, dipped them in the water; then, raising them to his mouth, took a deep, delicious drink.

George drank again and yet again; then, lying face downward, gazed into the stream. It was full of little fishes; golden, silver—there were so many that he could not even count them, and each was more beautiful than the other.

"This is jolly!" he thought. "It's just like a piece out of a story, only better."

He rose to his feet and stood for a moment thinking. "I know; I want to cross the stream," he said, when—lo and behold!—just in front of him there was a little bridge, exactly wide enough for one person at a time. He crossed it with Alexander at his heels; then, turning round to look back, found that the bridge had vanished!

This was a curious thing to happen, but George hadn't time to wait. He wanted to go on and on and find out where the wonderful music came from.

"Wu-uff!" barked Alexander, and it sounded for all the world as if he were saying: "What fun, George! What fun!"

On they dashed, first George in front and then his dog. Right across the meadow they went, and suddenly found themselves on a broad white road which went winding and winding along as far as ever you could see.

"This is like 'Over the hills and far away,'" laughed George. "Come on, old boy!" And on they ran again, so fast that the road looked as if it were unwinding itself quickly like a ball of ribbon.

"I expect we shall soon get there now," said[Pg 70] George. "We must be miles and miles away from home."

The road grew narrower and narrower until it became quite a little path, and this path led them up to a little green gate, which appeared suddenly in front of them as if it had popped up out of the ground.

"This must lead to just where I want to go," said George. He was quite accustomed to talking aloud now. Somehow his voice sounded different, and he felt as if he must talk, for it seemed as if some one—he didn't know who—was listening to him all the time.

Across the top of the gate was written in shining letters "Please open me."

George pushed it open and walked through; then he saw that on the other side was "Please shut me." He shut it carefully behind him and walked on.

Once more, in front of him, sounded the music, but clearer and louder, as if it were only round the corner—but there was no corner.

THERE STOOD A DELIGHTFUL LITTLE HOUSE

He found himself in a narrow, shady glade. The trees, the grass, everything was a cool, delicious green. It was like looking down a long tunnel lighted by a soft green light. The little path went straight down-hill as[Pg 71] far as one could see, and never seemed to end.

George was beginning to wonder where he was going to, and if he had not wanted to find out about the music he would have turned back, for it felt like tea-time. He could not remember at what hour he had started out; nor how he had got into the wood; nor did he know how he was going to find his way back. But he knew that it was close upon tea-time, which is quite a different feeling from breakfast and lunch-time, as you all know.

"I wish there was a house here," he thought. "I should like tea with plenty of jam and cake."

There was really no end to the surprises of this most wonderful day. The path went straight—as if it had been told—into a wide open space, and there stood a delightful little house with smoke curling up from its chimneys.

George stood still for a moment and looked at it with eyes wide open in surprise. Alexander rushed forward, barking joyfully, and jumped against the door.

George followed him, and then stood still[Pg 72] again, for painted on the door in tiny letters was GEORGE'S HOUSE.

"How funny!" he thought. "There must be another George living here. I hope he will be kind and give me tea."

He lifted the latch and walked inside. There was no one there, but in the middle of the most comfortable little room stood a table with the cloth laid; tea, bread and butter, cake, jam (two kinds)—quite a birthday tea, in fact.

Alexander was already seated in one of the chairs as if he were in the nursery at home and eager to begin.

"Well!" said George, "this is nice!" And before you could count 'two' he had seated himself at the table, poured out a cup of tea, and was spreading strawberry jam on to a large piece of fresh bread and butter. How they both enjoyed themselves! There never was such a tea!

When they had eaten all they could there was still plenty left on the table. It almost looked as if some one had been cutting bread and butter and cake for them all the time.

George remembered to say his grace, and then, all of a sudden, he felt very sleepy.

"It's not nearly bed-time yet, but I wonder if there's a bedroom. I should like to lie down just for a minute or two," he said. Alexander yawned and stretched himself.

George looked round, and there in the corner he saw a stair, so up he went and found himself in a little bedroom. The bed looked so comfortable that he lay down on it, while Alexander curled himself up at the foot with a sigh of content.

The wind blew gently in through the window, bringing with it the scent of sweet flowers. Really it was just like asking George to go to sleep.

He closed his eyes, and in a moment was far away in the Land of Dreams.

Once more was heard the strain of music, sweet and clear, and with it, wafted on the wings of the wind, came the sound of hundreds of tiny little voices laughing.

Father Time

GEORGE dreamed that night as he had never dreamed before. It was a curious dream, full of dragons, giants, fairies, aeroplanes, motor-cars, all mixed up together. But all the time he half remembered where he was and kept thinking: "I am in bed in the little house that belongs to George, and it must be a dream-house. If it is, then I am dreaming inside a dream."

Every time he thought this he woke up—or seemed to wake up—and then fell asleep again. Alexander dreamed about large bones and crackly biscuits. That was the kind of dream he liked best.

Morning came—but perhaps there had never been any night—and George really awoke, sat up, and rubbed his eyes. The sun was shining through the window, and Alexander had gone.

He washed his face and hands and went downstairs. The table was laid for breakfast with porridge and cream—a jug full!—eggs and bacon, toast, rolls hot from the oven, fresh butter, jam, and marmalade.

The Mr George who lived in this house was a nice person to know. George felt that he would like to stay here for quite a long time if he could only send a message to Mother and let her know where he was.

He sat down feeling quite delighted at having breakfast all by himself, and just as he was drinking his second cup of tea the door opened and in came Alexander.

"Oh, where have you been?" cried George. "Don't you want any breakfast?"

"Wuff! Wuff!" replied Alexander, which meant: "Don't ask me silly questions like that, but give me something to eat."

He ate a good breakfast and drank a whole saucerful of milk, which he hardly ever got at home.

After breakfast George thought it was time[Pg 79] to start again. He had quite forgotten about going home now. It seemed quite the right thing to put on his cap and set off again to—where, goodness only knows!

Alexander stood waiting by the door, and George said aloud: "Thank you, Mr George, for your kindness," just to show that he hadn't forgotten his manners; then they went out into the bright sunshine.

George's House stood in a lovely little spot. Birds called to one another from the branches of the high trees; rabbits scuttled in and out of their holes, played hide-and-seek, and even flopped just under Alexander's nose.

George took a deep breath: "Oh, I am enjoying myself," he cried. "Aren't you, Alexander?"

"Ra-ther!" barked Alexander, and ran round and round chasing his tail while all the rabbits sat and watched him. It certainly did seem as if he had spoken that time—but no!—it wasn't possible!

Off they went again. There were sure to be more adventures if one only kept on and on to the end of the wood. Little paths ran in all directions, and each one looked greener and nicer than the other.

"I expect they all go to the same place in the end," said George, and so, without waiting for a moment, he ran as hard as he could down the nearest at hand. It twisted and turned in all directions; sometimes it seemed as if it were turning round and coming all the way back again. At last it gave quite a little jump and went straight ahead.

They walked and ran, and ran and walked by turns; it grew lighter and lighter until they could see the sun shining on the—yes, it was!—the sea.

Now, if there is one place which is jollier than all the others it is the seashore on a sunny day. There is always paddling, bathing, digging, making castles and lakes; besides, the fun of getting caught by a splashy wave is worth while getting wet twice over.

Hurrah for the sea! You could almost hear it calling, for in the summer-time all the little boy-waves love to play with their friends the human boys. Dogs are welcome too if they will swim in after sticks.

In another moment George and Alexander were out of the wood and on the seashore. Such miles of hard yellow sand as far as one[Pg 81] could see, and a sea as blue, or even bluer than the sky.

Off came George's clothes, and in he splashed with Alexander after him. The water was as warm as toast, and made him feel like having five minutes more every time he thought of coming out.

George dried himself in the sun and put on his clothes, while Alexander rolled about in the sand and shook himself until he looked like a great mop with all its hair on end. But after a bathe there are usually biscuits, and there were certainly none here.

"I expect we shall find some," said George. "If we don't, we must go back to George's House and have dinner."

He turned to walk up the beach toward the long sand-hills which ran in a line along the shore, and there, sitting not far off him, he saw an old man. This old man had white hair, not very much of it, and a long beard which flowed down to his knees. He was holding something in his hand; George could not see what it was.

"Perhaps he's lost his way. Come on, Alexander; we'll go and ask him," said George.

He was quite a nice old man, and smiled[Pg 82] such a kind smile when George took off his cap politely and said: "Good-morning."

"Good-morning, little George," he answered.

"I say, do you know my name?" asked George in surprise. "Oh, are you the Mr George who lives in that little house in the wood, because I slept there. This is Alexander, my dog; he was there with me. He's a very well-behaved dog unless he sees a cat or a rabbit, and then it's an awful bother to get him back. Have you got a dog? And what is that thing you have in your hand? Oh, I forgot I was never to ask more than one question at a time. I am very sorry I was rude."

The old man smiled again. "No, my name is not George. The little house belongs to—well, you will find that out by and by. I haven't a dog of my own, but I know all about dogs. This is an hour-glass. It tells the time. You see the sand trickling down from one glass into the other. When all the sand has trickled through I turn the glass over, and it begins all over again."

"Oh, I say, how jolly!" cried George. "May I look? I've seen an hour-glass in a picture-book I have at home, but this is a real one, isn't it?"

"Quite real," answered the old man; "as real as you are, little George."

George gazed at the hour-glass for some time; then suddenly he remembered something. "Why, I know who is holding the hour-glass in the picture," he said. "It's Father Time.... Oh, you look just like him! Are you Father Time, please?"

"Well, that is what people call me," said Father Time, stroking his long beard and looking at George with a queer look, as if he were trying to see right inside him.

"Then you can really fly?" asked George. "Nurse always says that 'Time flies.' I don't see your wings ... but perhaps you don't need any," he added politely.

Father Time smiled very kindly, and spoke in a very soft, gentle voice: "Yes, I fly, and I have wings, though you cannot see them. The young people think that I fly far too slowly, and when they are grown up they think I fly too quickly.... But the sand in my hour-glass is always falling, falling, never quickly, never slowly."

"And do you have to look after all the clocks in the world?" asked George. "There are ever so many. We've got six in our house,[Pg 84] and Father and Mother have got watches as well."

"Yes," replied Father Time. "It gives me a great deal of work, but if it were not for me you wouldn't have any clocks and watches."

"Oh, that would be queer!" exclaimed George. "We should never know if it was time to go to bed or time to get up. Nurse wouldn't like that, for she loves everything to be 'on the tick,' she says. 'A stitch in time saves nine' is what she is always telling me."

"A great many people say that," answered Father Time. "If everybody remembered it, my old cloak wouldn't be as ragged as it is," and he showed George a number of holes and tears which certainly looked as if they needed mending.

Alexander whined and then barked: "Come on, don't talk so much, please!"

"Down, Alexander!" cried George. "We're going in a minute. Oh, please, can you tell me the way to——" And then he stopped, for he really didn't know where he wanted to go to.

"You had better go up the road over there," said Father Time, pointing. "You will find a finger-post which will show you the way. You can't miss it; it is quite easy to find. Good-bye!"

"Oh, wait a minute!" cried George, for old Time was already some way off. He turned and waved his hand.

"Time waits for no man!" he said. "Follow your fortune, little George!"

"He is a funny old man," thought George. "Follow my fortune? Whatever does he mean?"

Far, far off, he heard the sweet music once again. It sounded more inviting than ever. "It's like the story of Dick Whittington, only he had a cat and not a dog. I believe the music is saying: 'Follow your fortune, your fortune, oh, follow!' Come and look for the finger-post, Alexander!" And he ran up the sands toward the road.

Puck flew into the wood. "He's here!" he cried.

The fairies danced round him in delight. "Hurrah!" they cried. "Hurrah!" sounds different altogether and much nicer in their language. "Tell us all about it!"

So Puck sat down and told them all about George's adventures right from the beginning. If you have not remembered everything you must turn back and read it all again for yourself.

"Ker-ek!" croaked the old frog. "But what's all this about Father Time? How do you know he met Time. I don't believe it!" and then he nearly fell backward in surprise, for there stood the old man in front of him.

"Now do you believe?" said Puck's voice, and the fairies burst out laughing, for it was Puck himself all the time!

When the old frog had stopped coughing Father Time had disappeared, and Puck sat there smiling.

"What a clever Puck I am!" he cried, turning head over heels.

More Adventures

IT really was a delightful country to live in. There was no need to ask your way to anywhere—you just went. Almost before he knew where he was George found himself back in front of the little house.

Smoke was still curling up from the chimneys, so somebody must have been putting more coal on the fire—at least, it would seem so.

It was quite time for dinner; and, sure enough, dinner was ready. It doesn't matter what George had to eat—it would make you feel both hungry and cross if you knew.

When the meal was over George thought it was quite time to follow his fortune, but where and what was it?

"Oh, Alexander shall show me the way," he said, and he stepped outside into the garden, where that always hungry creature was cracking a large bone.

"Alexander, I mean to follow my fortune," he said, "but I don't know where it is. Can you help me?"

To his surprise, Alexander looked up, wagged his tail, and then said quite as plain as could be: "All right; let me finish this bone and then I'll come!"

George stared at him. "Can you really talk, Alexander?"

"Talk? Of course I can talk," he replied. "Who ever heard of a dog who couldn't talk? I've talked to you ever since I've known you, only I don't talk like a boy. I talk like a dog."

This was quite true, for he still had a 'doggy' voice, and there was a sound of "Wuff, wuff!" in everything he said.

"Good gracious!" cried George. "I never knew you were talking. I thought you were only barking."

"Well, barking is talking. What would be the use of my barking if it meant nothing?" replied Alexander rather crossly, for he hated to be interrupted in the middle of a meal.[Pg 91] "Sit down a minute and then I shall be ready."

George sat down and waited quietly. It was quite still everywhere; there was a soft little breeze which was just enough to set the flowers in the garden nodding their heads. It kissed George gently on the cheek, and then gave a puff which made the golden weathercock on the roof-top turn round and round until it must have become giddy.

"Now I'm ready," said Alexander, licking his lips and brushing his whiskers carefully, in case there might still be a fragment left of his meal.

"Alexander, can you tell me whose house this is?" George asked.

"Whose house?" said Alexander. "Why, you know. It's written on the door."

"Yes, I know that; but who is this Mr George?"

"You are, of course," laughed Alexander, and gave a jump of delight. "You are! Fancy not knowing that it was your own house! Ha, ha! What fun!" and he began running after his own tail, faster and faster, until he looked like a black Catherine wheel.

"Oh, I say!" cried George. "My house! Oh, I wish I could bring Father and Mother[Pg 92] to see it. Can't I send them an invitation to tea? But I don't see a letter-box anywhere, and I can't write a proper letter. Can you?"

"No!" replied Alexander. "I don't want to. I don't know why people want to write letters at all when they can go for walks and talk to one another—and have games and meals," he added.

"Oh, well, I must just tell them all about it when we get back again. Now we had better start for—you know, wherever my fortune is."

Alexander looked round him for a moment. "I think I know the way, but we may as well ask the weathercock, so as to be quite sure."

"Ask the weathercock? How can that help us?" George was becoming quite puzzled.

Alexander said nothing, but gave a short, sharp bark. There was a faint "Cock-a-doodle-doo!" from the roof in reply; then—could George believe his eyes?—the golden cock stepped off his little perch and fluttered down to their feet.

He was a smart little bird! All gold from the comb on his head to the spurs on his feet, and he twinkled and shone so in the sunshine that he was quite dazzling to look at. He flapped his wings, pecked Alexander playfully behind[Pg 93] the ear, and then crowed: "Cock-a-doodle-doo-oo-oo!" and it sounded for all the world as if he were saying: "How do you do-oo-oo?"

"George is going to follow his fortune," said Alexander. "Can you put us on the right road?"

"I'd better come with you for part of the way," replied the weathercock. "It's just along down there."

"How do you know the way so well, please?" asked George.

"I know the way to everywhere. A brother of mine stands on the roof of your home. Haven't you ever seen him point?"

"Yes, of course," said George; "I've often stood and watched him turning round and round."

"Well, you don't suppose he's doing that for fun, do you?" asked the cock, looking at him with a bright and shining red eye. "He's pointing out the way."

"I'm afraid I don't understand."

"Well, he's pointing out the way to there.... Every one wants to go there, some time or other. If you don't want to go, why did you ask me?"

"Come along!" said Alexander. "George will understand by and by. He's a stranger here, you know."

The weathercock strutted on ahead of them, and George and Alexander followed.

"He can talk too," said George. "Everybody seems able to talk here."

"Of course," replied Alexander. "Why shouldn't they? Everything and everybody talks in its own way if you only know how to listen. Why, the wind's talking all the time. Can't you hear it?"

George stood still and listened. "It does seem to be saying something. It sounds just like: 'Oh-oo! Oh-oo!'"

Alexander laughed—such a funny, wuffy laugh. "It's humming a tune to the trees. Can't you see them nodding their heads in time to the music? If the wind were angry they would be shivering and shaking with fright. Perhaps it will talk to us by and by."

"Come on!" cried the cock, looking round, "I have to get back to work or else the wind will be coming along and scolding me for wasting time."

They walked along down a winding path, up a little hill, down another, and there in front stood a post with a large finger pointing straight ahead.

"Here you are!" said the cock. "Go straight[Pg 95] on until you arrive there. The weather will be quite fine, and your fortune is waiting for you. If you want to get back ask any of my family you may meet and they will show you the way. Good-bye!" He flapped his wings, crowed "Cock-a-doodle-doo!" and disappeared.

George went up to the finger-post, and there, printed on it in large letters, was: "THIS WAY TO ONCE-UPON-A-TIME."

"Another adventure!" he cried. "Come on, Alexander!"—but Alexander was already scampering down the road, barking joyfully.

A Nice Dragon

IT was really very jolly in this Once-upon-a-Time Land, though nothing wonderful happened at first. There were beautiful green trees, scattered about everywhere in twos and threes as if they were keeping one another company; there were large fields full of flowers; little rivers bustling along as if they were in a great hurry to get somewhere, and then turning a corner and flowing quite slowly as if they had remembered that it didn't really matter after all; and far off in the distance, with snowy peaks glittering in the sunshine—mountains!

The road led them along up and down like a switchback. It was quite easy walking; in fact, the road almost seemed to walk by itself. Whenever they felt thirsty there was a spring of delicious cold water bubbling up by the roadside, and when they felt hungry there were apples, pears, blackberries, strawberries, and raspberries all growing and ready for anybody who would take the trouble to pick them.

"I think it's time we got somewhere," said George.

"We're nearly there," replied Alexander. "I know She lives not far from here."

"She? Who is She?" asked George.

"Why, Her, of course," and Alexander ran on ahead and round the corner before George could ask another question. Suddenly he heard a loud barking, and thinking that Alexander was chasing a rabbit, or perhaps a cat, he ran as hard as he could, turned the corner, and saw——

Well, I never! It was wonderful, and yet it was in Once-upon-a-Time Land, where things like this happen every day. It was just as one sees it in picture-books, only naturally it looked ever so much bigger than one expected.

"A dragon!" cried George. "I haven't got a sword or anything at all to fight with. If it begins to breathe fire it will burn me right up! And what is Alexander doing? Why, I do believe he's playing with it."

And so he was, and what was even funnier still, the dragon actually seemed to like it. Alexander ran down its long, long back, which rippled and shone in the sunshine like scales of golden flame, bit the end of its tail playfully, and barked right under its great nose. The dragon opened its great mouth, showing rows and rows of sharp, pointed teeth, and laughed a really jolly laugh.

"You seem to want a game," it said, in a great deep voice which sounded as if it came from somewhere half-way down its back. "Come on, little George; just wait until I uncurl myself."

It gave itself a shake and uncoiled all the twists in its back, which cracked like little pistols, bang! bang! then jumped once or twice in the air to stretch its legs.

"See if you can catch my tail!" it cried, and then began a regular game of 'Catch me who can!' The dragon didn't seem to run exactly, but moved along somewhat like a snake,[Pg 102] only ever so fast, with its tail hanging temptingly behind. Every time George put out his hand to catch hold of it, whisk!—away it went again! Alexander leapt this way and that way, and every time he came to the ground again found that the dragon was not where he expected it to be. Then the dragon began to make loops and curves of itself, as if it were writing all the letters of the alphabet with its long back.

At last all three lay down on the ground quite out of breath.

"I'm not so old as I thought I was," said the dragon. "I haven't had such a good game for a long time. Phew! I'm absolutely boiling hot!" and out came a long tongue like yards and yards of red flannel, and it smoothed its scales as far as it could reach.

"Alexander does just the same when he's washing himself," thought George.

"So you're going to look for your fortune?" said the dragon after a while.

"Yes," replied George, "I am. I hope Alexander will find his too."

"I hope so," smiled the dragon. "I like to see people who are looking for fortunes, though they don't always find them, even when they're[Pg 103] under their very noses. I knew a dragon once—it's not a long story—who went to look for his fortune."

"Was it in Once-upon-a-Time Land?" asked George.

"Of course," replied the dragon. "People don't understand dragons anywhere else. They tell the most stupid stories about us, as if we went about doing nothing but eat up people and breathe fire. You might as well say that dogs do nothing else but kill cats," he added, with a laugh.

Alexander looked very solemn, and as if butter would not melt in his mouth.

"Well, this dragon, as I was saying, went out to look for his fortune. He was quite a young dragon, and ought to have stayed at home as his mother told him. He had never been farther than the end of the valley where they lived, though of course he thought he knew all about everything.

"So his mother kissed him good-bye, told him to take care not to catch cold, and watched him disappear in the distance. It was a fine day, and the young dragon went along thinking of all the great things he was going to do, and bumping his head against[Pg 104] trees because he never looked where he was going.

"He met nobody and nothing for a long time. About midday he began to feel very hungry, and almost wished he were at home again. But at last, on the top of a hill, he saw a man standing by the door of a house; at least, he thought it must be a house, but he wasn't quite sure, for he had never seen one before. It was really a miller standing by his mill, whistling for the wind to come and turn the sails round.

"He was a friendly miller. He invited the dragon to rest for a while and have something to eat. After the dragon had eaten forty loaves and two hundred currant buns and drunk all the water out of the water-butt, he began to feel better, and told the miller what he was looking for.

"'Looking for your fortune, are you?' said the miller. 'Well, you've come to the right place, for the road to fortune starts from here and from nowhere else.'

"He saw that the dragon was quite young and rather vain, so he thought he would play a joke upon him.

"'Do you see those long fingers?' he said,[Pg 105] pointing to the sails of the mill. 'They are pointing out the way to your fortune.'

"'Oh!' replied the dragon. 'They are all pointing different ways. How can I tell in which direction to go? Does my fortune lie everywhere all around me?'

"'No, no,' said the miller. 'Just stand quietly here for a bit, and by and by you will learn all about it.' Then he went inside the mill and waited to see what would happen.

"Presently the breeze heard the miller whistling and came blowing along in answer to his call. The sails of the mill shook, and then, very slowly, commenced to turn.