| Title: | Short Stories |

| Early October, 1923 |

Transcriber's Notes:

Two-columns text has been converted to a single column.

Blank pages have been eliminated.

Variations in spelling and hyphenation have been left as in the

original.

A few typographical errors have been corrected.

The cover page was created by the transcriber and can be considered public domain.

Have you ever heard of one? If you have a gramophone you should have done, for this music pen is the super gramophone needle—its proper name being Tone Pen, and it is a tiny hollow pen of specially tempered metal. The reason why the Tone Pen is hollow is important. The solid needle dulls the tone, and after a while wears out the record.

The hollowness of the Tone Pen enables it to translate the most exquisite and delicate tones. By fixing the Tone Pen point outwards you get the greatest volume of sound, by turning it sideways you get a softer, mellower tone.

And, above all, you can play from 80 to 100 records with one Tone Pen. You can keep the gramophone going the whole evening without bothering to change the needle. You have to change the ordinary needle with every record. That means constant jumping up and down and fiddling with the gramophone. The Tone Pen saves you, saves your gramophone, gets the very best out of the records, and makes the words of songs beautifully clear, which are often unintelligible with other needles.

THREE TONE PENS ARE EQUAL TO THREE HUNDRED ORDINARY NEEDLES, AND ONLY COST ONE SHILLING THE CARD OF THREE

Postage 1-1/2d.

J. H. NICHOLSON, 26-28 Audrey House, Ely Place, Holborn, London, E.C.1.

If you are interested in wireless, or have a wireless set of your own, or want to try a set and are not sure how to start about it, get

RADIO BROADCAST

the Wireless Magazine

1/- MONTHLY

Specimen copy 3d. stamps

The World's Work, 20, Bedford St., W.C.2

RADIO FOR AMATEURS

By A. HYATT VERRILL.

Cr. 8vo. 7s. 6d.

With about 200 illustrations and diagrams

An up-to-date, concise, simply written book covering every phase of radio communication, with particular attention devoted to radio or wireless telephony.

THE RADIO PATHFINDER

By RICHARD H. RANGER.

Cr. 8vo. 7s. 6d. With numerous illustrations.

The book is written in simple, non-technical language that has the rare quality of being scientifically accurate yet intriguingly interesting. The illustrations are exceptionally good.

HEINEMANN LONDON

| THE IRON CHALICE | 3 |

| HAPSBURG LIEBE | |

| THE NORTH WIND'S MESSAGE (Verse) | 77 |

| DANFORD G. BRITTON | |

| IN MEMORY OF HENRY CLAY MANLEY | 78 |

| THOMAS McMORROW | |

| FIRES OF FATE | 90 |

| W. C. TUTTLE | |

| MAKE GOLD WHILE THE WATER RUNS | 112 |

| ROBERT RUSSELL STRANG | |

| THE ROAD TO MONTEREY (Part II) | 124 |

| GEORGE WASHINGTON OGDEN | |

| THE PACKET ADMIRAL | 144 |

| W. E. CARLETON | |

| HENRY HORNBONE'S ONE-MAN WAR | 151 |

| HELEN TOPPING MILLER | |

| FROM ONE TO ANOTHER | 159 |

| EARL C. McCAIN | |

| DESERT DRIFT | 167 |

| JOHN BRIGGS | |

| THE STORY-TELLER'S CIRCLE | 174 |

Readers of "Short Stories" are probably aware that "Short Stories" is only one of a family of magazines. The demand for specimen copies in answer to our advertisements of our other magazines, shows that our readers are eager to read the magazines published by the same House that publishes "Short Stories."

The other magazines are "The World's Work," 1/- monthly, "Radio-Broadcast," 1/- monthly, "The Health Builder," 1/- monthly, and "The Garden Magazine," 1/- monthly, and I think a short description will be much more useful and interesting to our readers than any number of advertisements.

To many thousands of readers "The World's Work" is an old friend, and we receive many letters of appreciation from readers all over the world, who have subscribed for years, and would not be without their "World's Work" for anything. If a number goes astray, we get no peace until they get their copy.

"The World's Work" seems to appeal strongly to people who live in the lonely parts of the world. It seems to keep them in touch with the world—with England. No story magazine can have the same link, but a magazine like "The World's Work" tells people what is going on everywhere.

Last year the famous Walter H. Page's Letters were published in "The World's Work," and caused an immense sensation. The exciting series of big-game hunting in Central Africa by Carl Akeley, the famous explorer, was also hugely appreciated. This year we started with the inner history of the Irish Rebellion, by Darrell Figgis, who knows, if any man does, the secret workings of the campaign, and who was closely associated with Michael Collins and Arthur Griffiths in the guerilla warfare against the British Government.

"The World's Work" deals with every kind of work and every kind of worker: with science, industry, agriculture, adventure, travel, politics, motoring—in fact it is a live wire between the world and the reader. It is written for the thinking man and woman, but not for the high-brow; it does not use too technical language, but, on the other hand, it goes far deeper than the information of the cheap, popular magazine.

THE WORLD'S WORK

1/- monthly

Specimen copy 3d. from

The World's Work (1913) Ltd., 20 Bedford St., London, W.C. 2

By HAPSBURG LIEBE

Author of "The Clan Call," "Alias Arizona Red," etc.

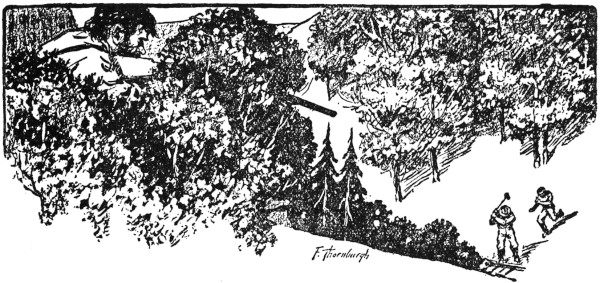

A STORY OF THE TENNESSEE MOUNTAINS THAT TAKES YOU INTO THE HEARTS AND LIVES OF BIG-HEARTED, QUICK-TEMPERED CLANSMEN; INTO A BITTER FEUD, AND INTO THE WAR THAT STARTED WHEN LITTLE BUCK WOLFE BROUGHT HIS LOGGING RAILROAD INTO WOLFE'S BASIN

The county's prisoners were passing the gate where Alice Fair and Arnold Mason were standing. They were going jailward, their hands and faces sweat-stained and begrimed from long hours at hard labor. The rattle of picks and shovels and irons drowned out entirely the sounds their weary feet made on the pavement. Arnold Mason saw only the pitiful lack of spirit in their downcast eyes. It touched deeply the sympathetic heart of this man who was of mountain blood, but to whom the Masons had given a city home. He had that tender and magnificent understanding of human sorrows that is so rare except in those who themselves have suffered.

But there was one of the passers-by who walked with his head proudly erect. He was very tall, rawboned and sunburned, and in his dead-black eyes shone the light of an anguish deep and sullen. His great right hand gripped the handle of the pick he carried over his shoulder as though it would crush the wood. He turned his pale, hard face toward the pair of lovers at the gate. Arnold Mason and the girl he hoped to marry saw that three parallel lines, three bow-shaded scars, stood out on his right cheek like streaks of white paint.

They were the marks of a wildcat's claws, put there years before. And it was by those marks, chiefly, that young Mason recognized the man as his own mother's son and her first born.

"Oliver!" he exclaimed.

The big mountaineer centered his gaze upon his youngest brother. To him, also, recognition had dawned. A queer smile parted his beard and mustaches and showed a flash of strong, white teeth.

"Hello thar, Little Buck Wolfe!" he cried sharply. "Leadin' a high life now, hain't ye?"

Mason stood there, as silent and as motionless as a stone, and watched the clanking line of prisoners until friendly trees along the street blotted out the sight. When he faced Alice Fair, he noted a decided change in her manner.

"He called you 'Little Buck Wolfe,'" she observed coldly. "Was that your other name?"

"Yes."

"I think it's horrid. Who was that?"

He told her. She winced, but he con[4]tinued, "My father's given name was Buck. He was a giant of a man, and he was my boyhood's ideal of what a man should be—naturally. I wanted to be named for him; I went without a name until I was nine. So they called me 'Little Buck.'"

"You told me that your people——"

"Were upright and honorable in their way," Mason cut in gloomily. "As I knew them, they were, certainly. I've never been back there. I had to study almost day and night, because I started to school so late. I—I guess I was so much interested in myself that I forgot them."

"And you didn't know until just now," pointedly, "that you had a brother in jail?"

"I've been out of town for three weeks, Alice, you'll remember," he muttered. "I came home only yesterday."

"Well," frowning, "what's the good of going over it? You can't expect me to marry you when you've got a brother in jail, here under our very noses. Honestly, can you?"

She held out to him the diamond ring he had given her an hour before. He accepted it mechanically, and mechanically put it into his pocket. Without another word, she went rapidly toward the house.

Arnold Mason, Little Buck Wolfe that was, walked slowly, with no clear thought as to direction, up the shadowy street. If there is anything that can change the gold of goodness in the mountain heart to iron, it is—this.

The high, barred window of Oliver Wolfe's cell opened to the east. At that window, his bearded face pressed against the bars, his eyes longingly watching the dim shape of Buffalo Mountain fade into the night, stood Oliver Wolfe. He did this every evening now, watched Buffalo Mountain, which was hardly more than a foothill, fade into the night.

Came the sound of footfalls in the corridor, and he turned his head. Just beyond the iron-latticed door, he saw the shapes of two tall men. A key grated in the lock, and he heard a voice.

"I'd like to be alone with him, Sheriff Starnes."

"Certainly, Mr. Mason," the officer answered courteously. "Call me when you want to go out."

The door opened and closed, the key grated in the lock again, and Oliver Wolfe stood face to face with his brother.

"Why did they put you here, Oliver?"

"For a-provin' I was the best man in town, surlily."

"I see. Assault and battery."

"With attemp' to kill," the prisoner added with a certain pride. "'Leven months and twenty-nine days, and eight o' the days done gone."

He put a hand on his brother's shoulder and shook him roughly.

"Nobody sent fo' you to come here," he said hotly. "Hain't ye afeard ye'll dirty them fine clo'es o' yore'n? You mis'able town dude, whyn't ye be a man, like I am?"

Arnold Mason said nothing to that. A moment of silence passed. Oliver Wolfe's black eyes ceased to stare contempt; perhaps some tender memory of their boyhood days together was at work in his brain.

"But mebbe you ain't as rotten as I thought ye was, Little Buck," he went on. "I thought you was pow'ful stuck-up, y' see. I'm a-goin' to tell ye somethin', and you listen:

"You know pap he used to be the law and its enfo'cement out at home. You know he used to deal out jestice wi' his fists when anybody done wrong, and you know he was allus square. He was king o' the section then. But he hain't no more. He's only the leader o' the Wolfe clan now, Little Buck. He—"

"The Wolfe clan!" Mason exclaimed surprisedly.

"The Wolfe clan," Oliver repeated impatiently. "Well, them Singletons, 'at lives at the upper end o' the basin, has been a-fightin' us fo' a long time. Tuck he's dead, and Biddle, and Simon, and Cousin Lije's Buster, and Aunt Jinny's Simmerly—every one of 'em buried wi' Singleton bullets in 'em. When I left home, pap he was a-layin' on the flat o' his back wi' a bullet in his shoulder. But le' me tell ye this right now—the Wolfe's they hain't a-goin' to quit fightin' ontel they hain't able to crook a trigger-finger no more!"

Oliver Wolfe clicked his teeth together savagely, clenched his fists, and began to pace the cell floor. After a minute spent thus, he went back to Mason and pursued.

"I was a dang fool. I slipped down to town here to buy some ca'tridges, got in a rucus, and got arrested—but it took three good men to do it, and don't ye fo'git that—and them a-needin' every Wolfe by name out thar to fight Singletons! The's a good many more Singletons an' the' is Wolfes,[5] y'see, and the' hain't but dang few Singleton's 'at cain't cut down a hangin' hosshair with a bullet. And so I'll come to the p'int at last.

"Little Buck Wolfe, yore people needs you. You quit these here fool ways o' yore'n, and git ye a rifle, and go out thar and fight wi' yore own flesh and blood!"

Mason straightened as though he had been struck. Just then a lamp was lighted in the corridor, and its rays showed the face of Oliver Wolfe to be jerking under stress of emotion.

"Well," Oliver demanded, "are you a-goin' to wear the boots of a man?"

The other turned toward the iron-latticed door, and called to the sheriff to come and let him out.

"Is yore name, dahlin' brother," sneered the jailbird, "Wolfe, or is it Mason?"

"Wolfe," answered the stalwart young man at the door. "Wolfe. Now and forever."

The bottom of Wolfe's Basin is two miles in length, one mile in breadth, and as level as a prairie. The rockbound and majestic Big Blackfern Mountain makes the eastern wall; the western wall is formed by great Lost Trail Mountain, which lifts high toward the heavens a bald peak called Pickett's Dome. A crystal-clear creek gushes from under a rugged gray cliff at the junction of the Big Blackfern and the Lost Trail, splits the basin's bottom in the centre, and flows out through a dizzily-portaled pass, the same being known as Devil's Gate.

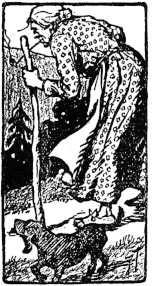

Old Alex Singleton and his people lived in twenty-two low and rambling log cabins near the south end of the basin. Old Buck Wolfe and his people occupied eighteen cabins of the same kind near the basin's north end, near the pass. Old Buck's mother lived alone save for a little black dog named Wag. She was sixty-nine, white-headed, as wrinkled as parchment, very sharp of feature and of tongue; she was called wise in her understanding of the curative properties of herbs, and she was a firm believer in supernatural tokens.

Granny Wolfe rose early on this fine summer morning. She slipped her bent old body into a dark-figured calico dress, tied a pair of coarse shoes on her rheumatic feet, wound a red bandana about her white head, bathed her face and hands and dried them on a hempen towel. She filled her clay pipe with homegrown tobacco, lighted it with a coal from the yawning stone fireplace, and took up a long sourwood staff. Another moment saw her entering the crooked, grass-lined path her feet had worn to the home of her favorite son.

A sharp yowl caused her to stop, face about, and bring her staff down hard.

"Durn ye, Wag, ye little devil," she muttered, "I left ye shet up inside! But it's bad luck to turn back, and I jest hain't a-goin' to do it. So yap as much as ye please, ye little devil!"

Now Old Buck Wolfe was a fiddler as well as a fighter, and when his mother had reached a point some seventy yards from his primitive house she was startled by hearing Buffalo Gals fiddled as she had rarely or never heard it fiddled before. Thereupon Granny Wolfe's seamed countenance showed signs of a great chagrin, and she began to talk to herself:

"I'll—be—durned! Ef the durned fool hain't got out o' bed and went to fiddlin'! Wisht I may drap dead in my tracks, ef he hain't! And he'll be a-fightin' them 'ar Singletons afore night, as shore as the Old Scratch hain't a grashopper! Well, I kep' him in bed as long as I could. The bullethole it's done healed over. Now, I shore do wonder what makes menfolks be allus a-wantin' to kill each other? The Lord ha' mussy on us!"

The fiddler sat in a crude, homemade chair in the cabin's front doorway. He was a huge man, and gaunt, and his long black hair and beard were not without threads of silver. His mother halted a few feet from him, and leaned heavily on her staff; she stared at him quite as though she had never seen him before.

"Reckon ye'd know my hide in a tan-yard?" laughed Old Buck Wolfe, dropping the instrument to his knee.

"Hain't you a purty thing, now—jest hain't you!" cried the old woman, with her own particular brand of scorn.

Her son's keen black eyes twinkled. "What's got the matter o' you?"

"You git back in bed!" snapped Granny Wolfe.

Old Buck narrowed his eyes. "When I'm able to fiddle," he said, "I'm able to[6] fight. Stick that in yore pipe and smoke it, mother. Hey?"

"I'll be durned!" shrilled Granny Wolfe. "You wildcat, ye're a fixin' to go fightin' ag'in! Sech a durned fool! And when is it ye're a-goin' to commencet a-fightin,' Buck Wolfe?"

"Us Wolfes," soberly, "is to meet here at dinner-time, and start fo' t'other end o' the basin. It'll be the last fight; d'ye onderstand that?"

The old hillwoman's voice was soft when she spoke again.

"Don't do it, honey," she pleaded, almost pitifully. "Don't. I wisht I may drap dead in my tracks ef I didn't see a star fall over this here house last night, honey; and that 'ar is a shore sign o' death. And I dreamp' o' seein' muddy water, and that's a bad sign, too. Don't do it honey!"

The giant in the doorway laughed outright. He didn't believe in the supernatural.

"My nose itches," he said, winking; "what's that a sign of?"

"Heh? Why, Buck Wolfe, it's a sign somebody is a-comin' hongry! Jest wait and see ef it don't come true. But them 'ar Singletons, don't tackle 'em ag'in!"

"I'd give a mule ef Oliver was here," her son muttered. He turned to address a meek little woman who had come up behind his chair. "Sary, that 'ar damned old blue-tailed hen's a-scratchin' up yore merrygolds ag'in."

Then he rose, kicked his chair over, and threw fiddle and bow to a nearby bed. He stepped to the ground, took his mother by her lean shoulders, and shook her slightly. His whole countenance was terrible.

"The Wolfes settled here fust!" he roared. "When I thrashed old Alex Singleton fo' a-sellin' me a jug o' cawn whisky wi' a leaf o' burley tobacker in it, he needed it. Ha! you fo'got pore little Tuck, brother Brian's boy, and the rest of 'em, a-layin' up thar in the old Blackfern's breast wi' hunks and hunks o' Singleton lead in 'em? Mother, ha' you fo'got?"

"But Tuck he'd killed one o' the Singletons, which was the very fust killin' of it all, too," Granny Wolfe returned sharply. "Asides, the Wolfes has put as many Singletons in the Lost Trail as the Singletons has put Wolfes in the Blackfern, and rickollect 'at! You'd shorely better let it lay right whar it's at, Buck Wolfe."

He glowered down upon her. "The Singleton had called Tuck a liar, mother, and you know it!" he snorted. "Now save yore breath, is my advice. The fight is to be, and it will be."

The old woman limped into the cabin, where she tried to comfort Sarah Wolfe, mother of Little Buck, the Arnold Mason that was.

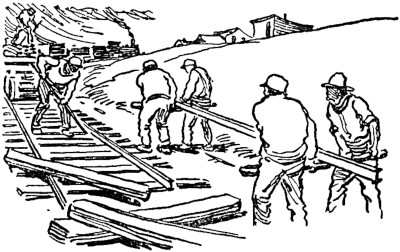

Noontime came, and twenty Winchester rifles were brought and stacked against a cedar in the narrow yard. Twenty men, some of them barely grown, sat here and there, on the doorstep, on the woodpile, on the ground; they were waiting for their leader to finish his mid-day meal, and Old Buck was showing his contempt for danger by eating more than usual.

When the Wolfes started toward the south end of the basin, the Singletons moved toward the north end. Like the Wolfe chief, Alex Singleton—a big-boned, broad-bodied man with deep, dark eyes and straggling, sunburned black hair and beard—was not without some of the qualities of a general and strategist. A Singleton sentinel on the side of Pickett's Dome gave the alarm by waving a red bandana, then raced down to join his kinsmen. A woman followed each of the sets of fighters. One of them was old Granny Wolfe. The other was the Singleton leader's only daughter.

The Wolfes' one-man advance guard ran back with the intelligence that the enemy was just ahead. Old Buck rushed his little force to the left, meaning to make a surprise attack on the Singleton's flank. Oddly enough, Alex Singleton gave the same order at the same time, with the result that the two sides lost each other, and spent hours in maneuvering more or less blindly; not a shot was fired, and the silence in the basin was the silence of the tomb.

Buck Wolfe's anxious mother saw that the shadow of bald Pickett's Dome was reaching for the fringe of jackpines that grew on the jagged crest of the Big Blackfern, and she knew it was almost four o'clock. Then, there broke out ahead of her the keen, sharp thunder of rifles—the two factions had met where there was no cover save for puny bushes, and it would probably be a battle of extermination. She forgot her rheumatism, dropped her long staff, and ran toward it.

Two others reached the midway point before Granny Wolfe reached it. One of[7] the two was a slender, barefooted young woman with deep blue eyes, copper-colored hair that hung down her back in a single thick plait, and a face that was quite finely handsome in spite of its tear-stains. The other sat astride a rearing, plunging black horse; he was young and stalwart, and an officer's shield gleamed over his heart.

"What's the big idea?" he was shouting. "What's the big idea, anyway?"

The daredevil personality of the newcomer awed the fighters. Even if they might have counted him out, there would have been no possibility of going on with the battle without danger to the two women. And to continue the fighting there in the open, where they had met by accident—well, the hillman is no coward, but he wants cover when he fights.

The two little clans acted wisely. As though by a common agreement, they crept off homeward without a word.

The old woman caught the rein of the now quiet horse.

"And who might you be, stranger," she cackled, "'at comes a-ridin' in here like a angel o' the Lord?"

He smiled very pleasantly. "Don't you know me?"

"Not from Adam's off ox, nor a side o' sole-leather!" declared Granny Wolfe.

"I know who it is," said the other of the three left upon the scene. "Granny, it's Little Buck!"

"La, la, la! You don't tell me it's Little Buck. I be consarned ef I'll believe it!" She shook her white head.

"And I know you, too," Wolfe said to the young woman. "Your name is Louisiana Theodosia Singleton, but they call you 'Tot.' You—er, you were my sweetheart when I was a boy. Don't you remember, Tot? Surely, you haven't forgotten the time when I thrashed Cat-Eye Mayfield and threw him into the creek—there at the sand-bar under the willow—for sticking pine-resin chewing gum into your hair! Don't you remember, Tot? Afterward, when we'd disposed of the villain," and here Wolfe's dark eyes twinkled engagingly, "you kissed me as a reward for my—er, gallantry!"

Louisiana Theodosia Singleton blushed and said nothing. Little Buck's grandmother was now convinced.

"Well ef it ain't you, shore enough," she cried. "Now didn't I tell yore contrary old pap 'at somebody was a-comin' hongry? But who'd ever ha' dreamp' you'd grow from the pesky boy you used to be into the fine-lookin' man ye are! You shore do 'mind me o' yore pore grandpap when he used to come to see me afore we was married. Look at him, Tot Singleton; don't you reelly think he's jest grand-lookin'?"

"You—you're a-doin' the talkin' now, Granny," said Tot Singleton, visibly embarrassed.

Wolfe smiled. But only for a moment. There came from somewhere near the foot of Lost Trail Mountain an old and broken voice that seemed a part of the peacefulness of the eternal hills; an old and broken voice that was filled with the holiness of a benediction:

"'And, lo, the star, which they saw in the East, went before them——'"

"That was pore Grandpap Bill Singleton 'at hollered," explained the old woman, putting her right hand up to meet that of her kinsman. "We calls him the 'Prophet', Little Buck."

She emitted a tiny shriek at his grip; he had forgotten her rheumatism. He apologized quickly, and held his hand down toward the young woman who had been his boyhood sweetheart. Tot Singleton glanced straight into his eyes, seemed suddenly afraid of him, and ran swiftly homeward. Wolfe faced his garrulous grandmother again and opened his lips to speak, but she cut him off short.

"Now don't that beat the devil? She acted like as ef she was afeared ye'd bite her head off, didn't she? Atwixt me and you, Little Buck, wimmen is sawt o' strange critturs. Say, dad-burn it, you jest wait here ontel I step back yander to the aidge o' the basin and git my stick, which same I draped—it lays at that 'ar slim poplar thar—and me and you we'll go to yore pap's house."

Her grandson rode to the foot of the Lost Trail, recovered the sourwood staff and brought it to her. He dismounted[8] then, and the two walked toward the settlement of the Wolfes, the horse following at the end of its rein.

"And so you're a real, shore-enough officer o' the United States law!" proudly observed Granny Wolfe as they picked their way through a thin copse of sumach.

"A deputy-sheriff, made that at the special request of the new Unaka Lumber Company, of which I am general manager," said Wolfe. He went on, "It was done in order that I might better protect the company's interests in the mountains. What lucky fellow got Tot Singleton, Granny?"

"Lumber was Colonel Mason's line; I might ha' knowed it'd be yore line, too," muttered the old woman. "Hey? Now hain't Tot purty! She hain't a bit like the rest o' the Singletons. Bless yore soul, Tot hain't never married nobody! And her mighty nigh it as old as you, Little Buck. Some says one thing about that, and some another; but me, I say it's acause she han't never seed nobody 'at was quite as good as the boy who beat the devil out o' Cat-Eye Mayfield and throwed him in the creek for a-stickin' pine rawzum chewin' gum in her hair! Ye see, honey, a mountain gyurl at sixteen is mighty nigh it a woman—why, I was married at sixteen—whilst a boy at the same age is gen'ally a durned fool. Hey?"

Wolfe laughed. "And what became of Cat-Eye Mayfield?"

"Him? Huh!" She turned up her thin old nose. "He still lives with his pap up whar the two mountains j'ines at. And he still pesters Tot half to death a-tryin' to git her to marry him. Tot she hates him wuss'n the Old Scratch. And she's been a-havin' a sight o' trouble wi' her heatherns, the same as I have wi' mine. She jest cain't stand the idee o' her people a-fightin' like they does. Some says it was Grandpap Bill Singleton 'at put it into her head; but me, I say it's jest natchelly the goodness of her, Little Buck.

"I know you've come back to he'p yore people, Little Buck," Granny Wolfe ran on. "You seed whar at yore duty laid. Well, we've got me and you, and Tot and her grandpap, on the right side o' the fence. But we'll have a awful time of it, shore. Yore pap he's turrible, turrible! It's allus him who begins the fightin' atwixt us and the Singletons. Them Singletons, 'cept Tot and her grandpap, the Prophet, is as quick to fight as a wildcat; but they don't never take the fust step at it, never."

Twilight, soft and peaceful, had set in when the pair arrived at Old Buck's low and rambling log cabin. Standing or sitting here and there in the yard, all of them grave and silent, was a score of men of the name Wolfe—one of their unwritten laws was that when an outsider married a Wolfe he lost his surname and took that of his wife; it was like that with the Singletons, too, that other wild, princely clan. The house was packed with women and children; and they, also, were grave and silent, save for one babe in arms that whimpered softly because its mother wouldn't give it the clock for a plaything.

The returned son of the Wolfe chief threw his horse's rein over one of the rotting gateposts, and entered the yard with his grandmother limping close behind him.

"I'll bet ye cain't guess who this here feller is!" the old woman chuckled—and told them in the same breath. "It's Little Buck!"

Little Buck had been recognized already. The clan favored him with one quick, sharp glance. There was no other demonstration just then.

Young Wolfe stopped before the doorstep, on which his huge, gaunt father sat as still as a stone image. Old Buck's elbows rested on his knees; his bearded chin was almost hidden in his great, knotty hands. The son who had been named for him saw that a tiny streak of dried blood ran from a wound somewhere under his left shirtsleeve straight to the point of his left little finger.

Then the man of the officer's shield put out his hand and said cordially, "How are you, father?"

The clan leader seemed not to have heard. The silence became oppressive. Little Buck Wolfe's lips quivered, and he saw his father dimly. Granny Wolfe made a choking sound in her leathery throat, and raised her sourwood staff threateningly.

"Buck Wolfe, you old fool," clipped her quick tongue, "you git right up from thar and shake hands wi' yore own flesh and blood, him 'at is a credit to you and me and[9] every other Wolfe 'at ever slapped the face o' the earth wi' a shoe-bottom."

The stern old mountaineer did not even change his stare.

"How are you, father?" again.

Wolfe the elder suddenly leaped to his feet, seized Little Buck's hand and wrung it savagely, and growled, "I'm all right, damn it; how're you?"

"All right," very quietly. Little Buck's face had brightened.

His mother, who never dared to speak ahead of her iron-hearted husband, came out to meet him then. He kissed her reverently on the forehead, and it brought to her mind an avalanche of memories of happier days; she stole hurriedly back into the cabin, in order that the menfolk might not see signs of the weakness that had come over her. Her son began a round of handshaking with his kinsmen. The ice was broken.

"Nath," bellowed the old clan leader, "you bring him a chair out here! The' hain't no room in the house; the wommen and young'uns is as thick in thar as fiddlers in Tophet. Set the chair so's he can lean back ag'in the wall and rest hisself, Nath. And bring me that 'ar jug o' yaller cawn licker out o' the cubb'ard, too, Nath—the visitor licker. Boy," to Little Buck, "ye'll have to look over my cussfired onperliteness, I reckon. I've been so cussfired mad all day 'at my dang breath would wilt fullgrown pizen-vine."

He dropped back to the doorstep. A few seconds later Little Buck accepted the chair his big and bearded brother Nathan brought for him. Old Buck then drew the corncob stopper from a one-gallon jug with his teeth, and held the jug toward his fifth son. The latter refused it courteously, and it was not pressed upon him. He saw Nathan smile good humoredly.

"Mebbe you're sawt o' like me," said Nathan, as he passed the jug to his Cousin John Ike. "I got on a rip-roarin' big dido last summer—I was so loaded I wouldn't ha' knowed a lightnin'rod agent from a beauty doctor. Whilst I was in that glorious fix, I drunk a bottle o' hawg cholery medicine by mistake, and so I jest hain't had no hankerin' 'atter licker sence."

This elicited a low rumble of laughter. The earthenware receptacle went around, and was returned to Old Buck almost empty. Old Buck raised it to a level with his eyes, looked toward Little Buck, and drawled the only toast he knew.

"'Here's to you, as good as you are, and to me, as bad as I am; and as bad as I am, and as good as you are, I'm as good as you are, as bad as I am!'"

Young Wolfe only smiled. Nathan responded for him, "Drink hearty."

Old Buck went on. "When a feller can say that 'ar toast straight, he natchelly hain't loaded. I don't never 'low none o' my people to git loaded. I tests 'em by that toast; and ef they cain't say it straight, I thrashes 'em. I thrashed Nath atter he'd got over his dido and his mistake last summer. Ax him, ef ye don't believe it."

Nathan pulled at his silky black beard, grinned, and changed the subject, "What'n Tophet brung ye back, Little Buck?" he asked.

The man addressed swept the half-circle before him with his eyes. They were all smiling upon him now, and he was glad indeed to note that they were disposed to be so friendly. He moistened his lips and began.

"I decided some little time ago to come back. I had heard, through Oliver, about——"

"How's Oliver?" broke in his father.

"Oliver's all right. I had heard, through Oliver, about the fighting, and I wanted to see——"

"You say Oliver he's all right?" interrupted his mother, who now stood in the doorway.

"Absolutely. The fighting didn't seem worth while to me, and I wanted——"

"I'm shore glad pore Oliver he's all right," said Oliver Wolfe's wife.

"——To see if I could do anything to stop it," Little Buck pursued doggedly. "When I was ready to start out here, I learned that the Thorntons, some of whom have owned the basin land since the days of the old North Carolina land grant, were about to sell out to some cattlemen, who wanted the basin for grazing purposes. I investigated, and found out that the cattlemen hadn't offered a very good price because of the trouble they expected to have with the Wolfes and Singletons——"

"Them cattlemen," his father cut in grimly, "had right good hoss sense."

"Well, I knew the basin better than any of them, and I knew the coves of the inner sides of the two mountains were filled with virgin white oak and yellow poplar, timber without a peer in the world. I organized a company—lumber was Colonel[10] Mason's line, you know, and it's mine, also—and we bought both timber and land from mountain's crest to mountain's crest at a very reasonable figure. Then we ordered machinery for a big sawmill, a geared locomotive and cars, and enough light steel rails to run a narrow-gauge road over the six miles that lie between this point and the new C. C. & O. Railway. Everything is in our favor. The logging is all either down grade or on a level; there never was a finer location for a mill and yards than can be had here in the basin; and the little railroad can follow the creek all the way down to the C. C. & O."

A number of the faces before him had hardened. He rose; it was like him to meet the adverse on his feet.

"But I haven't told you the best of it," he went on convincingly. "I have an agreement with the other members of the company by which I am to have any of the land that I may want, when the sawing is done, at two dollars an acre, and I'm willing to pass it on to you at the same price; also, I am willing to give you all work at good wages. I say I'm willing; I mean that I'm anxious. It's for you, my own people, that I'm doing—what I'm doing.

"I want to see every Wolfe by name living in his own comfortable cottage home, on his own little farm, here in Wolfe's Basin. I want us to have a school for the children, a little church, and a post office. I want us to have an ideal community here in this, one of the finest spots on the Almighty's earth. If you'll all stick to me, we'll have it. Now, men, I want to know who's going to stick?"

The eyes of all were turned upon Old Buck Wolfe. When he spoke, he would speak for the others. He sat with his shaggy head bent, a huge and actionless figure in the deepening dusk.

"Ef we don't fall in wi' yore idee, then what?" he asked, without raising his head.

"It's like this," Little Buck told him in a very businesslike voice: "my foster-parents, the Masons, sold every dollars' worth of property they had—except their home, and they even mortgaged that as heavily as it would stand—to get money enough to back me up, such was their faith in me. I've given them my promise that they shan't lose a single penny. If I don't get your help, I—I'll have to develop the timber interest without it. But I want your help!"

"Son," and the stern old mountaineer sat up straight, "onless the' happens to be somethin' ahind of it that I cain't yit see, we're all with ye, lock, stock, ramrod, barrel, and sights!"

"And I say God bless ye, Buck Wolfe!" cried a creaking, but happy old voice from behind him. "Nath, run to my house and let my little dawg out; he's been shet up all day, pore little devil."

Before he went in to super, the Arnold Mason that was exacted an ironclad promise from his father. Old Buck gave his word that, no matter what might happen, the Wolfes would nevermore take the first step in a fight with the Singletons.

The young general manager of the newly organized Unaka Lumber Company refused the visitor-bed that night, and crept up to his boyhood bed in the loft. His dreams were filled with dazzlingly pretty women who kept giving him back diamond rings.

Shortly after daybreak on the following morning, Little Buck Wolfe woke, sat up, reached for his clothing—and thought of Tot Singleton. He kept thinking of her. He caught himself saying aloud as he drew on his boots that she would never have turned him down because he had a brother in the county's chain-gang. Why, Tot would have clung to him but the closer on that account!

He meant to spend the morning in looking over the central part of the basin, where the big sawmill was to be built. After breakfast was over, he talked with his father for an hour; then he set out up the creek, on foot and alone.

When he came in sight of the gnarled old willow that shaded the sand-bar, he halted very suddenly. Sitting at the base of the tree was Tot! Her head was bent low, and there was an indescribable air of loneliness about her. He stood there and watched her thoughtfully for a full minute. She did not move even a finger.

He had reached a point behind a clump of blooming laurel a dozen paces from her[11] when she lifted her head. But she didn't look toward him. She went to dreaming again, and he was saddened by the signs of unhappiness he saw on her countenance.

Just when he was about to make his presence known to her, an angular, slouching figure stepped before her from the bushes beyond. The newcomer was dressed in run-over cowhide boots, blue denim trousers baggy at the knees and held in place by a pair of homemade suspenders, a striped cotton shirt without buttons, and a worn black hat with its rim pinned up desperado fashion in front. His black eyes were lustreless, opaque, and uncanny. His thin lips were twisted in a smile that was decidedly unpleasant.

"Hi thar, Tot!" he sneered. "Waitin' here fo' that 'ar town smarty, like ye used to, I reckon; hain't ye?"

Wolfe's strong, smooth face lost a part of its healthy color. Tot made no reply; it seemed almost that she did not know that Mayfield, her tormentor, was there.

"He throwed me in the creek oncet," Mayfield went on, "but he cain't do it now. I was jest a boy then. I'm a man now. I wisht he'd come along and try it ag'in!"

At last the young woman gave him her attention.

"Little Buck was a boy then, too," she said; "and he wasn't no bigger'n you was, neither. And he's a man now, too—you bet."

"I jest wisht he'd happen along——"

Wolfe had stepped from behind the clump of laurel, and Cat-Eye Mayfield had seen him.

"Well, Cat-Eye," Little Buck said evenly, "you've got your wish."

Mayfield's manner became one of defiance, bitterness, and desperation. He took from a pocket in his blue denim trousers a lump of sticky pine resin wrapped in a green poplar leaf; he threw the leaf aside, and in one quick movement deliberately pressed the resin deep into Tot Singleton's copper-colored hair!

And Tot, her blue eyes glowing and triumphant, had not lifted a hand to prevent it.

The mountain blood leaped madly in the heart of Little Buck Wolfe. He rushed at Mayfield like an enraged panther. His blows, the blows of a primitive man, fell upon Mayfield's sallow face like the pounding of a riveting-hammer, completely stunning him. Then he gathered the angular body up in his arms, bore it across the bar of sand, and hurled it into the water—just as he had done on that red-letter day of his boyhood.

Mayfield crawled sullenly out on the other side, gave the man who had whipped him a look of poisonous black hate, and slouched off up the creek's bank. Wolfe watched him until he was a good hundred yards away to see that he did not find a repeating rifle somewhere in the bushes; then he turned toward Tot.

In another moment he was standing face to face with her—smiling, blushing, finely handsome, barefooted Tot Singleton. He realized that the entire repetition of the little drama of his youth lacked but the climax—a kiss from Tot as a reward for his gallantry. She was looking straight into his eyes. Her slender, sunburned hands crept slowly to his shoulders. She stood on her toes, lifted her lips, and offered him his reward.

For she had no way of knowing that he had outgrown their juvenile affair; that he was for the present heart-broken because of the shallowness of another woman. He had fought for her, and he never could have made a stronger declaration that he still cared for her—it is a law of the cave. Besides, if he hadn't come there to meet her, as of old, why had he come?

Wolfe was not without chivalry. He could not strike down, like an assassin, the glory of her beautiful eyes; it was a glory that awed him, that could have come into being only after the longing, and the faith, and the waiting of years. He bent his head, and kissed her.

But he knew it was unfair, and he blamed himself heavily. He caught her hands as they were about to clasp at the back of his neck, and put them gently from him. She stepped backward, wondering, somehow pitiful. A disc of yellow sunlight fell through the branches of the willow, and burnished the copper of her hair.

"What made you do that, Little Buck?" she asked in the tiniest of voices.

He led her to the base of the tree, and they sat down together on the pure white sand. It seemed better to tell her the whole truth, and he told her the whole truth. Of every momentous thing that had occurred to him since his going away with the Masons to be their son, he told her; and he saw on her now slightly pale face more sympathy for him than disappointment for herself. Some there are who are built for sacrifice, but more there are who are not. Tot Singleton was.

When he had finished, he took from his pocket the ring that Alice Fair had given[12] back to him, and showed it to her. She merely glanced at it; she knew nothing whatever of the value, intrinsic or sentimental, of diamonds.

"Ef—ef I had that fool woman here," she said, her words fairly throbbing, "I—I'd whip her!"

To Wolfe the ring was in a manner sacred because of the memories associated with it; but it was a link that bound him to something that was lost and gone, and he decided that he had best do away with that link. Perhaps his inborn pride, the pride of the hillpeople, had its influence in the matter—he smiled a mirthless little smile, and flung the ring into the centre of the pool before him, the pool that used to be eight feet in depth and now was only two.

"And now I'll have to tell you good-by," he said, going to his feet. "I start back to Johnsville at noon, and I've a good deal of looking around to do here before I go."

Tot rose, said good-by to him, and went homeward.

A few rods down the creek, Wolfe came abruptly upon his father. The iron-hearted old hillman's face was ashen under his beard, and his black eyes were like two points of flame. He had followed his son. He had seen the kiss, from his little distance, though he had heard none of that which they said.

Old Buck waited until Tot Singleton was well out of hearing before he spoke.

"Mr. Mason," he announced, "listen to me. I said we was all with ye ef the' wasn't somethin' ahind of it 'at I couldn't see. The' is somethin' ahind of it 'at I couldn't see—mixin' up wi' that lowdown Singleton set. I promised I wouldn't start a fight with 'em no more, I know, and I won't. The feud it's dead, as dead as hell. And so are you. To me, you're dead. Acause I seed you kiss a lowdown Singleton."

"But——"

"Now le' me tell ye this here: you cain't never darken the door of a Wolfe no more, and you cain't bring no railroad nor no sawmill into this here basin ontel atter you've killed me. You've got my word fo' that, and it's the word of a Wolfe!"

The younger man shook his head dejectedly. "Dad," he began, "you don't know what you're talking about. I——"

"Hack it off right whar you're at!" Old Buck blazed. "I don't never want to hear the sound o' yore voice no more as long as the breath o' life's in me. You're dead, so far's I'm consarned."

The son tried hard to reason, tried harder to explain, all to no avail. The unlettered giant would listen to nothing. It angered Little Buck in spite of himself.

"I've given my word, just as you've given yours," he said spiritedly; "and, as I'm a Wolfe, just as well as you are, I'll keep my word if I live. The lumber track and the mill are coming, and it doesn't greatly matter who likes it or who doesn't."

Old Buck stalked off. His son then regretted that he had lost his temper.

Tot Singleton didn't go home just then. There was nothing she could do at home. Her mother was a very strong, stout woman who didn't want any "dreamin' gyurls a-piddlin'" in her household affairs; who sometimes worked in the woods with an ax, or hoed corn, or helped to make a run of whisky; and who lightened her daily burdens by the constant whistling of old-fashioned hymns.

The young woman absentmindedly destroyed a hundred or so of black-eyed mountain daisies by pulling off their defenseless heads between her bare toes; then she went back to her shrine—it was just that to this unspoiled creature who had been half child and half woman at sixteen and was very nearly the same today.

She stood leaning against the body of the willow, and thought over all that had happened there; looked at the marks Little Buck Wolfe's high-laced boots had made in the sand, at the marks of the struggle that had been so short and so one-sided. Soon she went to the edge of the creek, and peered into the crystal water. He hadn't known about the pool's being so shallow now, when he had thrown the ring into it.

She gathered up her calico skirts in one hand, waded in, found the ring, and hastened back to the sand-bar.

Tot looked at it closely now. It spar[13]kled so in the same yellow disc of sunlight that had burnished the copper of her hair a little while before; almost it hurt her eyes! Wonderment and something very different from wonderment wrote their signs alternately on her countenance. She pressed the ring on her engagement finger, and tried to imagine that it was her own engagement ring; but the iron truth wouldn't be forgotten even for a moment, and a wee smile of intense hurt came to the lips that the sweetheart of those happy other days had so recently kissed in so chivalrous a manner.

When she tried to get the ring off, it wouldn't come! Perhaps she didn't try very hard. Anyway, she laughed a little to herself, and her blue eyes were as bright as stars.

Tot Singleton went slowly up the bank of the creek, going homeward by instinct rather than by design. And she had not covered half of the mile when she met her father and the slouching young man they called Cat-Eye, both of whom were armed with rifles.

With a little gasp, she stopped suddenly and hid her left hand behind her. Her father was very angry, angrier than she had ever seen him before; she knew it the moment she saw his bearded face. It was all plain to her immediately. Mayfield had told her father that she had met one of the hated Wolfes halfway for the purpose of making love. Her face whitened with scorn.

"Well?" she asked.

"Le's see what ye've got on that 'ar third finger o' yore left hand, Louisiany," demanded Alex Singleton, slipping the butt of his repeater to the ground.

Tot remembered that she had been watching the changing colors of the stone when they came upon her. She stared silently and defiantly, and made no move toward obedience.

"It's his'n, that 'ar ring," frowned Mayfield. "He——"

"You shet yore snaky mouth!" Tot interrupted desperately.

"Le's see it, Louisiany!" Old Singleton's voice trembled now.

Still no move whatever from the young woman. The Singleton chief stepped to her, caught her left forearm in his big and sinewy hand, and brought the shining stone up near his eyes by force. The clear, pure beauty of the diamond held his attention for a few seconds; then he threw his daughter's arm from him roughly, as though the bare touch of it were a contamination.

"Take it off!" he blared.

"I—I cain't git it off!" cried Tot, a pink splotch in either of her cheeks.

"Then cut yore finger off!"

Cat-Eye Mayfield chuckled, and it maddened Tot Singleton.

"I don't want it off!" she declared.

The old mountaineer shot upward two inches. "You—you say you don't want it off?" he roared. "You say you don't want it off? By the Etarnal, you shain't never take that 'ar thing into no house o' mine as long as ye live! You're the only gyrul I got, but I'd ruther bury ye, 'an to see ye wi' that 'ar damned thing on yore finger!"

Being her father's daughter, Tot also straightened. She, too, could be obstinate. She pushed the ring a little farther up. Her voice was low and pinched.

"Ef you had ha' come to me and said, 'Louisiany, honey, I'd ruther ye wouldn't wear that,' I'd shorely ha' took it off don't matter how much trouble it was to me. But you a-sayin' what ye said, and the way ye said it, with Cat-Eye thar all a-grinnin' and a-gloatin'—well, pap, I shorely wouldn't be no kin to you ef I was to take it off now."

"All right. You cain't never darken the door o' none o' yore people no more," decreed Alex Singleton, shaking with a great rage. "Any o' yore kin 'at harbors ye will shore haf to reckon wi' me, and I'm a hard man to reckon with—you know that."

"I hain't a-goin' to take it off."

"All right!"

Old Singleton turned upon his heel with almost military precision, jerked his rifle into the hollow of his arm and strode away.

When he had gone, Cat-Eye Mayfield smirked and gave an exhibition of miserably poor judgment by trying to take Tot's hand. Tot struck him across the cheek so hard that her fingers left purplish red bars under the sunburn of his skin. For it was because of him that she was cast out, homeless, without a place to lay her head.

[14] "You'd better take yoreself away from here!" She clenched her hands and stamped one little foot. "You shorely better had! I'm done wi' you a-taggin' atter me, you—you sneakin' old rattlesnake of a tattle-teller! I wouldn't marry you to save yore life and mine, too. And this is the last time I'm a-goin' to take the trouble o' tellin' ye, Cat-Eye. Git."

Mayfield quailed before the fire of her finely glittering eyes. He took a few steps backward, watching her as though he feared she would spring upon him and rend his loosely knit body to pieces; then he turned and went straight toward the foot of Lost Trail Mountain. After he had gone a hundred yards, Tot saw him make a careful examination of his rifle.

Now one doesn't examine a gun like that when he means to shoot squirrels, not when he knows already that the gun is loaded and in order. Tot Singleton fell upon the idea that Cat-Eye Mayfield meant to watch the gate for Little Buck Wolfe, and shoot him from ambush. Mayfield was as unscrupulous a man as ever drew life's breath, and this was just the thing for him to do under the circumstances, she knew.

And Little Buck would start for Johnsville at noon!

After having searched the central part of the basin in vain, she decided that to protect him from the danger would be more sensible than to try to warn him of it. Of course, she couldn't go to the Wolfes' settlement. Besides, there was a strong chance of his being killed while trying to protect himself. In another moment she was running hard toward the nearest cabin, which was Grandpap Singleton's, and which, she thanked whatever gods there were, was not more than a quarter of a mile away; and she kept well to cover, in order that her irate father might not see her.

When she burst into the poor little house, the white-headed, white-bearded old hillman was poking the embers in the wide stone fireplace for a baked potato; he, like Granny Wolfe, lived alone and did for himself because he didn't want to be in the way. He looked around and slowly straightened his lean figure, and the fire-blackened hickory stick fell clattering from his unsteady hand.

"Tot Singleton," he demanded anxiously, "what in the name o' Fiddlin' Bob Taylor is the matter o' you?"

"I want yore old rifle, Grandpap," panted Tot.

"Now jest what're you a-plannin' to shoot wi' my old rifle, I'd like to know?"

"A rattlesnake—mebbe."

"A rattlesnake—mebbe! Heh! Take the rifle out o' the rack up thar over the mantel." He motioned toward it. "My pore old arms is so stiff and screaky wi' the rheumatiz 'at I cain't hardly reach up far enough fo' to scratch my pore old head no more."

His granddaughter stood on her bare toes and took down the long-barreled Lancaster muzzle-loader. She ignored the powderhorn and leathern bullet-pouch the Prophet had taken from a peg in the log wall and was holding out to her. The one load that was in the rifle would be enough. Tot, like the rest of the Singletons, didn't miss.

But as she turned toward the door, her grandfather caught her by an arm and held her firmly. His suspicions were at work.

"Wait, Tot, honey," he said. "You've got to tell me about it fust. It hain't no common rattler you're a-goin' to shoot—mebbe!"

She had been afraid to let him know, because of his strict religiousness. The earnest pleading, the deep love for her in his old eyes, now urged her to confide in him. She told it in a few words, for there was precious little time to be wasted.

"And so he's come back here to save his people, Little Buck has." Grandpap Singleton seemed very much affected. "I tell ye, Tot, honey, they needs him, as shorely as you're a foot high. Well, we'll he'p him ef we can. Shorely, a man ort to believe in a-fightin' fo' the right as well as prayin' for it. Heh?"

The Prophet certainly was not in one of his wandering fits now. He caught up a worn felt hat and pulled it low on his white head, and took the rifle masterfully from Tot's hands.

"Come wi' me," he ordered, almost with the snap of youth.

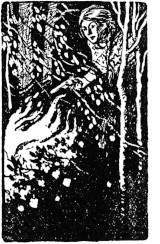

The pair of them hurried across the little vegetable plot, and were soon swallowed up by the trees and laurels of the mountainside.

"Ef the's any killin' to be done," muttered the aged mountaineer, "I'll do it myself. You're young, Tot, honey, whilst I'm as old, mighty nigh it, as Methusalem's house cat. But I can yit see how to shoot[15] purty tol'able straight. Heh! Do ye know what they used to call me fo' a nickname when I was a young man? 'Cracker,' that's what. Acause I was a crack shot. It was said I was the man who invented shootin' squirrels in the middle o' the eye!"

Considering that he had long been a sufferer from rheumatism, that scourge of the aged, the pace that Grandpap Singleton set and kept was truly surprising.

When they drew up stealthily behind a scrubby oak and peered down the Lost Trail's side of Devil's Gate, they saw just what they had expected to see. Crouched above a stone the size of a barrel, on which lay his repeating rifle on its side, was Cat-Eye Mayfield, motionless, waiting in a diabolical patience.

"We've got to ketch him mighty nigh in the act itself," whispered Grandpap Singleton, "so's the'll be enough real proof to send him to jail. We hain't got no real proof as yit, ye know, Tot. We'll jest wait here ontel he picks up his rifle, which same he'll do when Little Buck comes in sight, and 'en we'll make him put up his hands and call Little Buck up to arrest him. Heh? Shorely. He's a-plannin' to let Little Buck have it when he slows his hoss to ford the creek down thar."

Tot kept a watch on the trail below, which lay in plain view before her for several hundred yards. A few silent minutes went by; then she motioned to her kinsman to get ready.

She saw him kneel, lay the long barrel across a moss-covered stone, rest one shoulder against the scrubby oak's body, and bend his head until his right cheek touched the rifle's stock. After he had trained the old weapon properly, he raised his white head and turned his eyes upward without spoiling his aim; and Tot heard him speak in the lowest of undertones:

"Lord, ef I haf to do it, You'll onderstand, won't Ye? And ef I am in the wrong, which I'm purty shore I hain't, I ax Ye to fo'give me. Aymen."

The young woman wiped a dimness from her blue eyes, and looked toward the trail again. She bent and whispered nervously:

"He's a-comin' fast. He hain't more'n a hundred steps from the Gate. Now you watch Cat-Eye Mayfield, Grandpap Singleton, and don't you let him k-k-kill Little Buck!"

"You leave it to me!"

Mayfield picked up his rifle, drew the hammer back, and began to settle himself like a cat settling for a spring.

"Drap that 'ar gun, Cat-Eye!" cried Grandpap Singleton.

Tot pulled aside a laurel branch, in order that the would-be assassin might see the frowning muzzle that bore upon him. Mayfield was in no haste to turn his sallow face toward them; he looked at them only long enough to see who they were, and did not drop his rifle. Perhaps it was because he did not believe the religious old man would shoot; perhaps it was because his thirst for revenge was so great at that moment that his narrow mind had in it no room for any other thought.

"Drap that rifle, Cat-Eye!" Grandpap Singleton cried again.

Still Mayfield did not obey. The horseman was now almost to the ford, and reining in. Mayfield's round head seemed to sink halfway into his shoulders—he began to look along the sights.

"Shoot!" Tot urged frantically.

The old Lancaster cracked like a giant's whip. Cat-Eye Mayfield dropped his rifle now. He turned a dumfounded, ashen face toward the two Singletons, and babbled something unintelligible. Then—although the bullet had only passed through the upper part of his right arm, thanks either to Providence or to a dimness in the old mountaineer's eyes—Mayfield sank to the stones. The sight of his own blood had made him limp.

The Prophet rose unsteadily. The strain on his feeble mind was telling. He stretched wide his lean arms, and the bright sun threw his shadow down the incline in the form of an inverted cross.

He called to the man in the Gate, "Come up here, Little Buck Wolfe," thickly, "and arrest me fo' mudder!"

At the sound of the shot, Wolfe looked up quickly. He saw the gaunt old man go tottering to his feet, saw Tot standing with her hands[16] clutching at her calico dress below her throat; but because of the creek's dashing he did not hear the Prophet's agonized cry. Wolfe dismounted, fastened his horse's reins to a sapling, and hurried up the rocky steep.

The young woman and her grandparent had come down to where Mayfield lay groaning.

"He hain't dead," said Tot. "He's jest bad hurt. And you'd shore better take him along to town with ye, Little Buck, and jail him, ef ye don't want to be ambushed some other time."

Poor old Grandpap Singleton fell to his knees beside the man he had shot. "He hain't dead!" he rejoiced. "He hain't dead!" His hands were clasped against his hollow breast. His joy was even more pathetic than his grief had been before it.

Wolfe understood fully. He touched the now quiet figure on the ground with the toe of his boot.

"Get up!" he ordered.

Mayfield rose, his right arm hanging limp at his side. Wolfe ripped the shirtsleeve from the injured member, folded one of his own white handkerchiefs and placed it over the wound, and used the torn-out sleeve for a bandage. Mayfield, who was fast recovering from his fit of weakness, watched every move of the deft, strong fingers with old hatred in his lusterless, uncanny eyes.

The first-aid work was barely finished when the high-pitched voice of Granny Wolfe came from a point a few rods above:

"La, la, la! And so ye got him, durn him, did ye, Grandpap Bill Singleton!"

She limped down to them, her little dog, Wag, happy at her heels.

"Ye needn't to mind a-tellin' me about it, Bill Singleton," she chattered, "a-cause I already know, me a-bein' a good guesser. And so the rawzum-chawin' devil's pup—was a goin' to layway Little Buck, was he? You, Cat-Eye Mayfield, quit that a-lookin' at me like as ef ye could bite my whole head off."

She turned toward her grandson, who greeted her gravely.

"I tried to find you before I left," he said, and then told her of his father's change of heart.

"Consarn his old fool hide!" the old woman exploded.

Wolfe picked up Mayfield's rifle, threw the loaded cartridge out of the chamber, and let the hammer down carefully. Then he held the weapon out toward Tot Singleton.

"Take that home with you," he requested. "Mayfield can get it when he comes back."

Tot didn't take the rifle. Her lower lip began to quiver, and she looked away. "But I cain't never go home no more, Little Buck," she murmured.

"You can't go home!" he exclaimed in amazement.

She told him haltingly why. A very little smile curled Wolfe's mouth at the corners.

"So you, too, are an outcast," he said, half-sympathetically, half-resentfully. "But don't feel so badly about it! We always have our compensations, little girl. I wonder if—will you go along with me, Tot?"

She answered simply, "I'd go anywhar with you."

Grandpap Singleton took the rifle. Granny Wolfe addressed her kinsman:

"Ef you're a-goin' to town, you'd shore better start. I seed yore pap's old blue-tailed hen a-settin' on the fence a-pickin' her feathers this mornin', and I've heerd two treefrogs a-hollerin', and them's all good signs o' rain."

Wolfe shook hands with the two old people, and escorted his prisoner and her who had been his boyhood sweetheart down to the Gate trail, where his horse stood pawing the black earth impatiently.

"Get in the saddle, Cat-Eye," he said. "You're not able to walk."

"I hain't a-goin' to Johnsville—" Mayfield began, when Wolfe tapped his deputy's badge with a forefinger and cut in, "Get in the saddle!"

He pushed his coat back far enough to reveal the butt of a revolver that the high sheriff had found for him and urged him to wear. Mayfield obeyed awkwardly and ungraciously. With Tot Singleton walking trustfully beside him, Wolfe led the horse down the winding Gate trail, which soon entered a dark green tunnel formed[17] of laurel, giant ferns, and hemlock branches.

When they had put three miles behind them, Wolfe said to his companion, "I suppose you've guessed where I'm taking you."

"Yes," with a sidewise glance of admiration at his clearcut profile. "You're a-takin' me to them folks who 'dopted you, over in town. And ef they can make me over into the same sawt they made you into, I—I'll swaller all o' my feelin's ag'inst bein' a charity objeck, and he'p 'em all I can."

"That's the spirit!" he said with a good deal of enthusiasm. "You stick to that!"

Wolfe hired a light vehicle at the first farmhouse, and they reached quiet, lazy Johnsville an hour after the fall of darkness. It was a fine, starry night; contrary to Granny Wolfe's prediction, it hadn't rained. They went straight to the big, old-fashioned white house of the Masons, which lifted its gables so proudly above its setting of maples that one was inclined to wonder whether it wasn't scoffing at the heavy mortgage that was upon it!

The colonel and his wife were sitting on the unlighted veranda. He was tall, straight, gallant, courteous. She was rather little, gentle, sweet, a born mother who had never had any children. They were of the old South.

"Father," said the adopted son, as the trio reached the foot of the veranda steps, "here's a man with a pretty bad arm. Call Doctor Rice, won't you?"

Colonel Mason didn't wait to ask questions. He ran toward the phone, switching on the veranda lights as he passed through the hallway. The trio walked up the steps. Tot Singleton blinked in the strange white glow that shone from two frosted globes on the veranda ceiling. Cat-Eye Mayfield glared like an animal in a corner. Wolfe approached Mrs. Mason, who was at the same time approaching him.

"This is Miss Singleton, mother," he said. "I—I thought you wouldn't mind caring for her a little while as you cared for me for so long."

The colonel's little wife turned to Alex Singleton's daughter, took her hands, bent forward and kissed her on the brow. Tot stared; then a tear traced a crooked line down the road-dust of either cheek. No other woman had ever kissed her, not even her own stout, whistling mother, that she remembered. In that instant her whole weary, fiery mountain heart gave itself in everlasting love and devotion to Mrs. Mason.

"Let's go into the house, dear," softly said the older woman.

They went in. The colonel hastened back to the veranda.

"Rice is coming," he announced. To Mayfield, "Please sit down, sir."

The three of them sat down. The colonel slyly studied the wounded man's face, and he found it interesting. Soon the doctor arrived.

Rice dressed the hillman's arm in record time, and was paid on the spot for his services—by the young fellow he had always known as Arnold Mason. Wolfe then went with Mayfield into the dining room, where they had supper. Immediately after they had finished the meal, Mayfield was shown to a bedroom upstairs and in the back half of the house.

"Don't bother to run away," and Wolfe smiled a very pleasant smile. "You may go home tomorrow. I won't give you any trouble over trying to pot me; you see, I understand fully just how hard a prison term is for any mountain man! You won't try to do me harm in the future, will you? I want you to promise me that."

"Shore," Mayfield nodded. "I promise. You're a good feller, Little Buck, a dang good feller."

Mayfield had expected anything but mercy. But he was not too bewildered to grind his teeth and fling a vile, whispered curse at the door when Wolfe closed it behind him.

When Wolfe went back to the veranda, the lights had been cut off to keep away a swarm of annoying summer beetles. He saw that the colonel and a slender figure in white sat in rockers near the front steps.

"Miss Singleton—who wants me to call her Tot, like everybody else does—" began Colonel Mason, "has told me about the difficulties you had and—er, expect to have. It looks bad, Arnold; there's no denying it. You can't arrest and imprison your own people, of course. Frankly, I don't quite see how you're going to manage it, son."

[18] Wolfe stepped to the veranda post and put his back to it.

"You've always believed in me," he said earnestly. "I want you to continue to believe in me. I'm not to the barrier yet. There are six miles of narrow-gauge road to be built before the barrier is reached—the Devil's Gate, you know. No use worrying over things in the distance, father, eh? This is what I've got to do—when I get to the barrier, I'll cross it, or go under it, around it, or through it. I don't know how. I know only that it must be done."

"By George, sir!" The colonel brought a hand down on his knee for emphasis. "Of course, I'll keep faith in you! That pass—the Devil's Gate—was beautifully named, wasn't it? But there's one thing, Arnold, I must ask you to remember. That your life is of more value to us, infinitely, than our money. Don't forget it, son."

There followed a few minutes of silence save for the night song of a mocking bird somewhere in the maples. Then Tot Singleton, who now wore shoes and stockings and a white dress that Mrs. Mason had found for her, sat up straight in her chair and addressed the dimly-shining officer's shield.

"Let me tell you, Little Buck," she said, "you'll shorely wish you'd put Cat-Eye Mayfield in jail the minute you got to town. I'd bet my life ag'in a safety-pin 'at Cat-Eye Mayfield ain't in the house right now. As long as he can go whar he pleases, yore life ain't wo'th nothin'. I tell you, after you've done what you've done tonight fo' him, he'd foller you to the bottomest hole in Tophet to git to shoot you in the back. Hate you? Why, he's hated you ever sence he can rickollect. It's all the' is to him, that hate fo' you. As Grandpap Singleton says, the sourest vinegar in the world is made out o' molasses—a-meanin', o' course, hate made out o' l-love. Cat-Eye thinks he l-loves me, y' know——"

If the lights had been on, they would have seen that she was blushing terribly; she had made a bad mess, she thought, of telling them how it was.

The last word had barely left her lips when there came from the velvety darkness of the lawn the voice of an eavesdropper, a snake, Mayfield himself, who had stolen out by way of the back stairs:

"Ef ever she told the truth in all o' her borned days, Little Buck Wolfe, she told it then. Ye might as well make yore fun'ral 'rangements afore ye come into the hills ag'in, acause I'll certainly git you!"

Wolfe ran down the steps and disappeared in the blackness. Colonel Mason flashed on the veranda lights, and brought out a shotgun. But Mayfield and the night were too closely akin, and they failed to catch even a glimpse of him.

"I have always held out," muttered the colonel, when they had again gathered on the veranda, "that there was no man without a little that was good somewhere in his make-up. I admit now that I was mistaken."

Little Mrs. Mason came out then. She put a hand on Tot's arm.

"I've got a room ready for you upstairs," she said. "Would you like to go to bed now? You must be pretty tired."

"Yes'm," Tot replied absentmindedly.

She displayed no interest whatever in the beautiful blue-and-white bedroom that the good woman at her side told her to consider her own. She barely noticed the dainty night-dress that Mrs. Mason took from a drawer and hung across the back of a chair for her. Wondering at her sudden abstraction, the colonel's wife smiled a gentle, "Good night, my dear!" and left her to herself.

Tot Singleton was thinking of Mayfield. She had long ago given up trying to stop hating him; he wouldn't let her stop hating him. For years he had dogged her like a shadow; she hadn't been able to go anywhere, it seemed, without his following her. A thousand times he had profaned the sacred spot under the whispering willow—with his feet, with his voice, with his opaque and uncanny eyes, with his thoughts. Over and over she had tried to insult him, in order that she might be rid of him; but there was, apparently, nothing about him that could be insulted. No, he wouldn't let her leave off hating him!

And now Mayfield was free again; free to wait in the laurels beside the trail, or behind a stone above it, with his coward's soul red with the spirit of murder, and a rifle in his hands.

Little Buck Wolfe would go to the mountains in the morning to bring Mayfield back; he would be shot from ambush; the cost of his kindliness and his fearlessness would be his life. She was absolutely[19] sure of it, and her conclusion was certainly not far-fetched. Well, she would save Wolfe again. She was one of the very few persons in the world who could approach Cat-Eye Mayfield, now that he knew the hand of the law was against him, without great danger of being killed. She herself would arrest Cat-Eye. If he didn't submit to arrest, she would—but he would submit. It would be easy enough to find him. The mountains and their dense forests were as an open book to her; no man of the Wolfes Basin country knew them better.

To the outsider, the decision of this unlettered, but strong-souled young daughter of the hills is perhaps rather startling. But to Tot there was nothing so very extraordinary about it. To her, duty was duty, and nothing more—or less.

When Mrs. Mason rapped lightly at the door of the blue-and-white bedroom on the following morning, she received no response. She opened the door and went in, and found the bed not only empty, but undisturbed. Shortly afterward, the colonel's wife found that Tot's calico dress was gone; and in its place lay the white garments and the shoes and stockings that Tot had worn the evening before.

Mrs. Mason hurried downstairs and met Wolfe in the hallway. He seemed anxious.

"Mother," his voice troubled, "when I woke this morning, my revolver was gone from my holster, and the deputy shield from my coat. What do you suppose became of them? Do you think Mayfield——?"

"I believe I can explain, Arnold," she interrupted breathlessly. "The girl, too, is gone!"

"After Mayfield!" he cried.

"I have no doubt of it, Arnold. She probably thinks your officer badge gives her plenty of authority!"

There was a heavy step on the veranda. A big and poorly-dressed man, wearing a sunburned black beard and carrying a rifle by its muzzle, appeared on the threshold.

"Whar's my little gyurl?" he asked jerkily.

The colonel's wife looked with instant pity upon him. There was something very forlorn about Alex Singleton, the repentant. His gaunt and haggard face, his ragged clothing, his run-over cowhide boots, all were covered with the dust of travel. Just under his eyes, which were wide and hungry-looking, his cheeks were mottled faintly, and it was chiefly by this pathetic little token that Mrs. Mason read the story of his remorseful sorrow. He stared straight at her; he appeared to be wholly unaware of the presence beside her of old Buck Wolfe's son.

"Whar is she at?" he asked again, this time almost in a whisper.

"She went back to the hills last night," Mrs. Mason answered kindly.

"I'd ort to be shot fo' a-runnin' her off," muttered Alex Singleton. In louder tones, "Might I ax ye fo' a big drink o' whisky, mis'?"

Mrs. Mason's eyes twinkled. "I think we have some. Sit down and wait, and I'll go for it."

It was then that she noticed that his left shirtsleeve had been ripped open to the shoulder; that a rawhide thong did service as a tourniquet just above his left elbow; and that his left forearm, wrist and hand were swollen and discolored.

"Copperhead bit me as I was a-creepin' through a fence jest outside o' town," the mountaineer explained apologetically. "Got me afore I knowed it was anywhar nigh me. That's what I wanted with a big drink o' whisky, mis', it a-bein' good fo' snakebite."

"Oh, you must have Doctor Rice!" the little woman cried frightenedly. Already she was fairly pushing him toward a veranda chair that Wolfe had hurriedly provided; he sat down as obediently as a child would have done. "Arnold, phone Doctor Rice——"

"But there's no time to be lost in waiting for Rice, mother," said Wolfe. "Look at that arm! I can treat snakebite; I've got some potassium permanganate that I bought to take to the hills with me——"

He ran to his bedroom and returned with a small bottle. Alex Singleton rose angrily.

"I hain't a-goin' to let you do it!" he declared.

"You'll have to," replied Wolfe. "You don't want to die, do you?"

"But thar's whisky——"

"Whisky," old Buck Wolfe's son interrupted, "is as bad as it is good. It stimulates the heart action, but it spreads the poison through the system rapidly. This[20] permanganate—we just cut right through the marks of the fangs with a knife; then we draw out as much poison as will come; then we fill the wounds with this stuff, and pretty soon you'll be as good as new. You see, you evidently got the tourniquet on quick, which is a big thing."

"Me, a Singleton, and you, a Wolfe?" The mountain man was suffering much. He was a stranger in a strange land, dazed and bewildered, and heart-broken because of his treatment of his only daughter. He weakened.

"You'd do that fo' me, a Singleton? Ef you would, I hain't a-goin' to be lowdown enough to keep ye from it. Yank out yore knife and cut the whole danged arm off, Little Buck, ef ye want to!"

He held out the swollen, discolored hand. Wolfe took a sharp knife from his pocket, and with it split the fang-marks two ways. With his mouth he succeeded in drawing out some of the virulent yellow poison. After that he filled the wounds with permanganate crystals. The colonel came up and tried to help.

"We'll loosen your thong at intervals," smiled Wolfe. "There's some poison in that arm that the permanganate won't reach, but it won't hurt much if we let it into the circulation a little at a time. It's the shock of the whole dose, you know, that kills."

Some hours later, the leader of the Singletons put out his good right hand.

"Boy," he said with a great deal of feeling, "you've got one friend, anyhow, which no time, nor no change, nor no thing on earth can ever take away from ye. I want ye to shake wi' me, Little Buck."

They shook.

"Now will ye please tell me, ef ye know," Singleton went on, "how come it Louisiany left here in the night?"

Wolfe told him briefly.

"Cat-Eye Mayfield!" growled the big hillman. "Well, I reckon I'm a-goin' to haf to kill Cat-Eye sometime. Goodness knows I hates to do it, but fo' pore little Louisiany I will, as shore as green apples. Le' me tell ye this here, folks—thar's the lowdownest man 'at ever stuck a boot-track on the face o' the world."

After two more hours, the rawhide thong was removed entirely. Singleton's constitution was like iron. He rose, and took up his rifle and hat.

"I guess I'll be a-movin' toward home," he drawled softly. "I feel good enough to thrash my weight in wildcats now. I shore won't fo'git this."

"Better wait until tomorrow," advised the always hospitable colonel.

"I'll go with you," said Wolfe. "Tot may need help, you know. We'll separate at the Gate, in order that my people——"

"No!" old Alex broke in stoutly. "You cain't go to the mountains now. Mayfield would be plumb shore to snipe ye off, plum' shore. You must stay here fo' three days, at least. I tell you, I knows jest edzactly what I'm a-talkin' about, Little Buck."

"But he wouldn't have got away, if I hadn't been such a boob!" frowned Wolfe. "It's up to me, as the saying is, to bring him back."

Singleton shook his head. "Oh, no! Ef I'm a-goin' to be yore friend, you must le' me have my way about it. Don't be a-skeered but what Louisiany can take blamed good keer o' herself. Cat-Eye, he wouldn't hurt her, anyhow. He knows me too dang well to hurt her. And so good-by to ye all!"

Half a minute later, he had left the house and was hurrying toward the great, dim-blue ranges.