The Project Gutenberg eBook of Essay on the Principles of Translation, by Alexander Fraser Tytler

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Essay on the Principles of Translation

Author: Alexander Fraser Tytler

Release Date: March 20, 2021 [eBook #64890]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

Produced by: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ESSAY ON THE PRINCIPLES OF TRANSLATION ***

[i]

EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY

EDITED BY ERNEST RHYS

ESSAYS

ESSAY ON THE PRINCIPLES

OF TRANSLATION

[ii]

THE PUBLISHERS OF EVERYMAN’S

LIBRARY WILL BE PLEASED TO SEND

FREELY TO ALL APPLICANTS A LIST

OF THE PUBLISHED AND PROJECTED

VOLUMES TO BE COMPRISED UNDER

THE FOLLOWING TWELVE HEADINGS:

TRAVEL ❦ SCIENCE ❦ FICTION

THEOLOGY & PHILOSOPHY

HISTORY ❦ CLASSICAL

FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

ESSAYS ❦ ORATORY

POETRY & DRAMA

BIOGRAPHY

ROMANCE

IN TWO STYLES OF BINDING, CLOTH,

FLAT BACK, COLOURED TOP, AND

LEATHER, ROUND CORNERS, GILT TOP.

London: J. M. DENT & CO.

New York: E. P. DUTTON & CO.

[iii]

[iv]

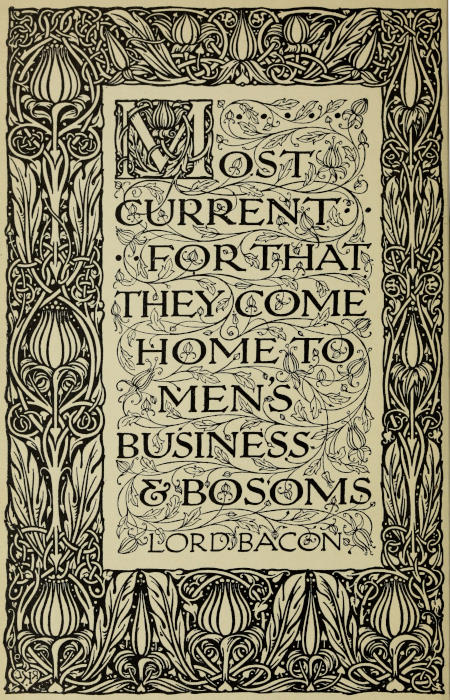

Most current for that they come

home to men’s business & bosoms

LORD BACON

[v]

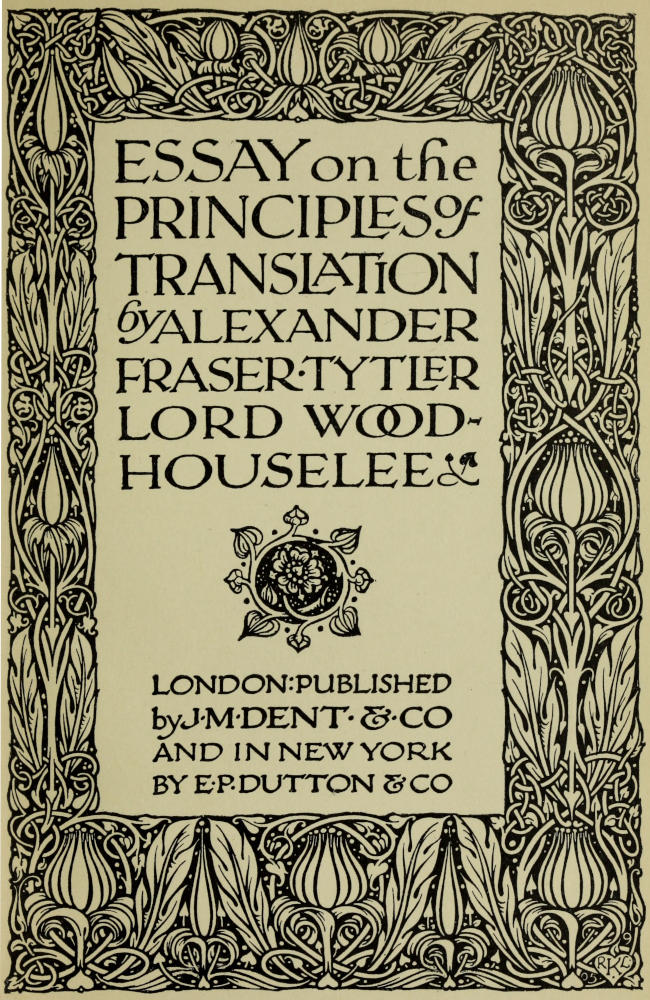

ESSAY on the

PRINCIPLES of

TRANSLATION

by ALEXANDER

FRASER·TYTLER

LORD WOODHOUSELEE

LONDON: PUBLISHED

by J·M·DENT·&·CO

AND IN NEW YORK

BY E·P·DUTTON & CO

[vi]

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

BREAD STREET HILL, E.C., AND

BUNGAY SUFFOLK.

Alexander Fraser Tytler, Lord Woodhouselee,

author of the present essay on Translation, and of various

works on Universal and on Local History, was one of that

Edinburgh circle which was revolving when Sir Walter

Scott was a young probationer. Tytler was born at Edinburgh,

October 15, 1747, went to the High School there,

and after two years at Kensington, under Elphinston—Dr.

Johnson’s Elphinston—entered Edinburgh University

(where he afterwards became Professor of Universal

History). He seems to have been Elphinston’s favourite

pupil, and to have particularly gratified his master, “the

celebrated Dr. Jortin” too, by his Latin verse.

In 1770 he was called to the bar; in 1776 married a

wife; in 1790 was appointed Judge-Advocate of Scotland;

in 1792 became the master of Woodhouselee on the death

of his father. Ten years later he was raised to the bench

of the court of session, with his father’s title—Lord Woodhouselee.

But the law was only the professional background

to his other avocation—of literature. Like his

father, something of a personage at the Royal Society of

Edinburgh, it was before its members that he read the

papers which were afterwards cast into the present work.

In them we have all that is still valid of his very considerable

literary labours. Before it appeared, his effect on

his younger contemporaries in Edinburgh had already

been very marked—if we may judge by Lockhart. His

encouragement undoubtedly helped to speed Scott on his

way, especially into that German romantic region out of

which a new Gothic breath was breathed on the Scottish

thistle.

It was in 1790 that Tytler read in the Royal Society[viii]

his papers on Translation, and they were soon after

published, without his name. Hardly had the work seen

the light, than it led to a critical correspondence with

Dr. Campbell, then Principal of Marischal College,

Aberdeen. Dr. Campbell had at some time previous

to this published his Translations of the Gospels, to

which he had prefixed some observations upon the

principles of translation. When Tytler’s anonymous work

appeared he was led to express some suspicion that the

author might have borrowed from his Dissertation, without

acknowledging the obligation. Thereupon Tytler

instantly wrote to Dr. Campbell, acknowledging himself

to be the author, and assuring him that the coincidence,

such as it was, “was purely accidental, and that the name

of Dr. Campbell’s work had never reached him until his

own had been composed.... There seems to me no

wonder,” he continued, “that two persons, moderately

conversant in critical occupations, sitting down professedly

to investigate the principles of this art, should hit upon

the same principles, when in fact there are none other to

hit upon, and the truth of these is acknowledged at their

first enunciation. But in truth, the merit of this little

essay (if it has any) does not, in my opinion, lie in these

particulars. It lies in the establishment of those various

subordinate rules and precepts which apply to the nicer

parts and difficulties of the art of translation; in deducing

those rules and precepts which carry not their own

authority in gremio, from the general principles which

are of acknowledged truth, and in proving and illustrating

them by examples.”

Tytler has here put his finger on one of the critical

good services rendered by his book. But it has a further

value now, and one that he could not quite foresee it was

going to have. The essay is an admirably typical dissertation

on the classic art of poetic translation, and of literary

style, as the eighteenth century understood it; and even

where it accepts Pope’s Homer or Melmoth’s Cicero in a[ix]

way that is impossible to us now, the test that is applied,

and the difference between that test and our own, will

be found, if not convincing, extremely suggestive. In

fact, Tytler, while not a great critic, was a charming

dilettante, and a man of exceeding taste; and something

of that grace which he is said to have had personally

is to be found lingering in these pages. Reading them,

one learns as much by dissenting from some of his

judgments as by subscribing to others. Woodhouselee,

Lord Cockburn said, was not a Tusculum, but it was

a country-house with a fine tradition of culture, and its

quondam master was a delightful host, with whom it was

a memorable experience to spend an evening discussing

the Don Quixote of Motteux and of Smollett, or how to

capture the aroma of Virgil in an English medium, in

the era before the Scottish prose Homer had changed the

literary perspective north of the Tweed. It is sometimes

said that the real art of poetic translation is still to seek;

yet one of its most effective demonstrators was certainly

Alexander Fraser Tytler, who died in 1814.

The following is his list of works:

Piscatory Eclogues, with other Poetical Miscellanies of

Phinehas Fletcher, illustrated with notes, critical and explanatory,

1771; The Decisions of the Court of Sessions, from

its first Institution to the present Time, etc. (supplementary

volume to Lord Kames’s “Dictionary of Decisions”), 1778; Plan

and Outline of a Course of Lectures on Universal History,

Ancient and Modern (delivered at Edinburgh), 1782; Elements

of General History, Ancient and Modern (with table of

Chronology and a comparative view of Ancient and Modern

Geography), 2 vols., 1801. A third volume was added by

E. Nares, being a continuation to death of George III., 1822;

further editions continued to be issued with continuations, and

the work was finally brought down to the present time, and

edited by G. Bell, 1875; separate editions have appeared of the

ancient and modern parts, and an abridged edition in 1809 by[x]

T. D. Hincks. To Vols. I. and II. (1788, 1790) of the Transactions

of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Tytler contributed

History of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Life of Lord-President

Dundas, and An Account of some Extraordinary

Structures on the Tops of Hills in the Highlands, etc.; to

Vol. V., Remarks on a Mixed Species of Evidence in Matters of

History, 1805; A Life of Sir John Gregory, prefixed to an

edition of the latter’s works, 1788; Essay on the Principles of

Translations, 1791, 1797; Third Edition, with additions and

alterations, 1813; Translation of Schiller’s “The Robbers,” 1792;

A Critical Examination of Mr. Whitaker’s Course of Hannibal

over the Alps, 1798; A Dissertation on Final Causes, with a

Life of Dr. Derham, in edition of the latter’s works, 1798;

Ireland Profiting by Example, or the Question Considered

whether Scotland has Gained or Lost by the Union, 1799;

Essay on Military Law and the Practice of Courts-Martial, 1800;

Remarks on the Writings and Genius of Ramsay (preface to

edition of works), 1800, 1851, 1866; Memoirs of the Life and

Writings of the Hon. Henry Horne, Lord Kames, 1807, 1814;

Essay on the Life and Character of Petrarch, with Translation

of Seven Sonnets, 1784; An Historical and Critical Essay on

the Life and Character of Petrarch, with a Translation of a few

of his Sonnets (including the above pamphlet and the dissertation

mentioned above in Vol. V. of Trans. Roy. Soc. Edin.), 1812;

Consideration of the Present Political State of India, etc., 1815,

1816. Tytler contributed to the “Mirror,” 1779-80, and to the

“Lounger,” 1785-6.

Life of Tytler, by Rev. Archibald Alison, Trans. Roy. Soc.

Edin.

|

PAGE |

| Introduction |

1 |

| CHAPTER I |

| Description of a good Translation—General Rules

flowing from that description |

7 |

| CHAPTER II |

| First General Rule: A Translation should give a

complete transcript of the ideas of the original

work—Knowledge of the language of the original,

and acquaintance with the subject—Examples of

imperfect transfusion of the sense of the original—What

ought to be the conduct of a Translator

where the sense is ambiguous |

10 |

| CHAPTER III |

| Whether it is allowable for a Translator to add to

or retrench the ideas of the original—Examples

of the use and abuse of this liberty |

22 |

| CHAPTER IV |

| Of the freedom allowed in poetical Translation—Progress

of poetical Translation in England—B.

Jonson, Holiday, May, Sandys, Fanshaw,

Dryden—Roscommon’s Essay on Translated

Verse—Pope’s Homer |

35[xii] |

| CHAPTER V |

| Second general Rule: The style and manner of

writing in a Translation should be of the same

character with that of the Original—Translations

of the Scriptures—Of Homer, &c.—A just

Taste requisite for the discernment of the

Characters of Style and Manner—Examples of

failure in this particular; The grave exchanged

for the formal; the elevated for the bombast;

the lively for the petulant; the simple for the

childish—Hobbes, L’Estrange, Echard, &c. |

63 |

| CHAPTER VI |

| Examples of a good Taste in poetical Translation—Bourne’s

Translations from Mallet and from

Prior—The Duke de Nivernois, from Horace—Dr.

Jortin, from Simonides—Imitation of the

same by the Archbishop of York—Mr. Webb,

from the Anthologia—Hughes, from Claudian—Fragments

of the Greek Dramatists by Mr.

Cumberland |

80 |

| CHAPTER VII |

| Limitation of the rule regarding the Imitation of

Style—This Imitation must be regulated by the

Genius of Languages—The Latin admits of a

greater brevity of Expression than the English;

as does the French—The Latin and Greek allow

of greater Inversions than the English, and admit

more freely of Ellipsis |

96 |

| CHAPTER VIII |

| Whether a Poem can be well Translated into

Prose? |

107[xiii] |

| CHAPTER IX |

| Third general Rule: A Translation should have

all the ease of original composition—Extreme

difficulty in the observance of this rule—Contrasted

instances of success and failure—Of the

necessity of sacrificing one rule to another |

112 |

| CHAPTER X |

| It is less difficult to attain the ease of original

composition in poetical, than in Prose Translation—Lyric

Poetry admits of the greatest

liberty of Translation—Examples distinguishing

Paraphrase from Translation, from Dryden,

Lowth, Fontenelle, Prior, Anguillara, Hughes |

123 |

| CHAPTER XI |

| Of the Translation of Idiomatic Phrases—Examples

from Cotton, Echard, Sterne—Injudicious use of

Idioms in the Translation, which do not correspond

with the age or country of the Original—Idiomatic

Phrases sometimes incapable of

Translation |

135 |

| CHAPTER XII |

| Difficulty of translating Don Quixote, from its

Idiomatic Phraseology—Of the best Translations

of that Romance—Comparison of the Translation

by Motteux with that by Smollett |

150 |

| CHAPTER XIII |

| Other Characteristics of Composition which render

Translation difficult—Antiquated Terms—New

Terms—Verba Ardentia—Simplicity of Thought

and Expression—In Prose—In Poetry—Naiveté[xiv]

in the latter—Chaulieu—Parnelle—La Fontaine—Series

of Minute Distinctions marked by

characteristic Terms—Strada—Florid Style, and

vague expression—Pliny’s Natural History |

176 |

| CHAPTER XIV |

| Of Burlesque Translation—Travesty and Parody—Scarron’s

Virgile Travesti—Another species of

Ludicrous Translation |

197 |

| CHAPTER XV |

| The genius of the Translator should be akin to that

of the original author—The best Translators

have shone in original composition of the same

species with that which they have translated—Of

Voltaire’s Translations from Shakespeare—Of

the peculiar character of the wit of Voltaire—His

Translation from Hudibras—Excellent

anonymous French Translation of Hudibras—Translation

of Rabelais by Urquhart and

Motteux |

204 |

| Appendix |

225 |

| Index |

231 |

[1]

ESSAY ON THE

PRINCIPLES OF TRANSLATION

INTRODUCTION

There is perhaps no department of literature

which has been less the object of cultivation,

than the Art of Translating. Even among the

ancients, who seem to have had a very just idea

of its importance, and who have accordingly

ranked it among the most useful branches of

literary education, we meet with no attempt to

unfold the principles of this art, or to reduce it to

rules. In the works of Quinctilian, of Cicero,

and of the Younger Pliny, we find many passages

which prove that these authors had made translation

their peculiar study; and, conscious themselves

of its utility, they have strongly recommended

the practice of it, as essential towards

the formation both of a good writer and an

accomplished orator.[1] But it is much to be[2]

regretted, that they who were so eminently well

qualified to furnish instruction in the art itself,

have contributed little more to its advancement

than by some general recommendations of its

importance. If indeed time had spared to us any

complete or finished specimens of translation

from the hand of those great masters, it had been

some compensation for the want of actual precepts,

to have been able to have deduced them

ourselves from those exquisite models. But of

ancient translations the fragments that remain

are so inconsiderable, and so much mutilated,

that we can scarcely derive from them any

advantage.[2]

To the moderns the art of translation is of

greater importance than it was to the ancients, in

the same proportion that the great mass of

ancient and of modern literature, accumulated up

to the present times, bears to the general stock

of learning in the most enlightened periods of

antiquity. But it is a singular consideration,

that under the daily experience of the advantages

of good translations, in opening to us all the[3]

stores of ancient knowledge, and creating a free

intercourse of science and of literature between

all modern nations, there should have been so

little done towards the improvement of the art

itself, by investigating its laws, or unfolding its

principles. Unless a very short essay, published

by M. D’Alembert, in his Mélanges de Litterature,

d’Histoire, &c. as introductory to his translations

of some pieces of Tacitus, and some remarks on

translation by the Abbé Batteux, in his Principes

de la Litterature, I have met with nothing that

has been written professedly upon the subject.[3][4]

The observations of M. D’Alembert, though

extremely judicious, are too general to be considered

as rules, or even principles of the art;

and the remarks of the Abbé Batteux are employed

chiefly on what may be termed the

Philosophy of Grammar, and seem to have for

their principal object the ascertainment of the

analogy that one language bears to another, or

the pointing out of those circumstances of construction

and arrangement in which languages

either agree with, or differ from each other.[4]

While such has been our ignorance of the

principles of this art, it is not at all wonderful,

that amidst the numberless translations which

every day appear, both of the works of the

ancients and moderns, there should be so few

that are possessed of real merit. The utility of[5]

translations is universally felt, and therefore

there is a continual demand for them. But this

very circumstance has thrown the practice of

translation into mean and mercenary hands. It

is a profession which, it is generally believed,

may be exercised with a very small portion of

genius or abilities.[5] “It seems to me,” says

Dryden, “that the true reason why we have so

few versions that are tolerable, is, because there

are so few who have all the talents requisite for

translation, and that there is so little praise and

small encouragement for so considerable a part

of learning” (Pref. to Ovid’s Epistles).

It must be owned, at the same time, that there

have been, and that there are men of genius

among the moderns who have vindicated the

dignity of this art so ill-appreciated, and who

have furnished us with excellent translations,

both of the ancient classics, and of the productions

of foreign writers of our own and of

former ages. These works lay open a great field

of useful criticism; and from them it is certainly

possible to draw the principles of that art which

has never yet been methodised, and to establish[6]

its rules and precepts. Towards this purpose,

even the worst translations would have their

utility, as in such a critical exercise, it would be

equally necessary to illustrate defects as to

exemplify perfections.

An attempt of this kind forms the subject of

the following Essay, in which the Author solicits

indulgence, both for the imperfections of his

treatise, and perhaps for some errors of opinion.

His apology for the first, is, that he does not

pretend to exhaust the subject, or to treat it in

all its amplitude, but only to point out the

general principles of the art; and for the last,

that in matters where the ultimate appeal is to

Taste, it is almost impossible to be secure of the

solidity of our opinions, when the criterion of

their truth is so very uncertain.

[7]

CHAPTER I

DESCRIPTION OF A GOOD TRANSLATION—GENERAL

RULES FLOWING FROM THAT

DESCRIPTION

If it were possible accurately to define, or,

perhaps more properly, to describe what is

meant by a good Translation, it is evident that

a considerable progress would be made towards

establishing the Rules of the Art; for these

Rules would flow naturally from that definition

or description. But there is no subject of

criticism where there has been so much difference

of opinion. If the genius and character of

all languages were the same, it would be an easy

task to translate from one into another; nor

would anything more be requisite on the part of

the translator, than fidelity and attention. But

as the genius and character of languages is

confessedly very different, it has hence become

a common opinion, that it is the duty of a

translator to attend only to the sense and spirit

of his original, to make himself perfectly master

of his author’s ideas, and to communicate them

in those expressions which he judges to be best

suited to convey them. It has, on the other

hand, been maintained, that, in order to constitute

a perfect translation, it is not only[8]

requisite that the ideas and sentiments of the

original author should be conveyed, but likewise

his style and manner of writing, which, it is

supposed, cannot be done without a strict

attention to the arrangement of his sentences,

and even to their order and construction.[6]

According to the former idea of translation,

it is allowable to improve and to embellish;

according to the latter, it is necessary to preserve

even blemishes and defects; and to these must,

likewise be superadded the harshness that must

attend every copy in which the artist scrupulously

studies to imitate the minutest lines or traces of

his original.

As these two opinions form opposite extremes,

it is not improbable that the point of perfection

should be found between the two. I would

therefore describe a good translation to be, That,

in which the merit of the original work is so

completely transfused into another language, as

to be as distinctly apprehended, and as strongly[9]

felt, by a native of the country to which that

language belongs, as it is by those who speak the

language of the original work.

Now, supposing this description to be a just

one, which I think it is, let us examine what are

the laws of translation which may be deduced

from it.

It will follow,

I. That the Translation should give a complete

transcript of the ideas of the original work.

II. That the style and manner of writing

should be of the same character with that of the

original.

III. That the Translation should have all the

ease of original composition.

Under each of these general laws of translation,

are comprehended a variety of subordinate

precepts, which I shall notice in their order, and

which, as well as the general laws, I shall

endeavour to prove, and to illustrate by

examples.

[10]

CHAPTER II

FIRST GENERAL RULE—A TRANSLATION

SHOULD GIVE A COMPLETE TRANSCRIPT

OF THE IDEAS OF THE ORIGINAL WORK—KNOWLEDGE

OF THE LANGUAGE OF THE

ORIGINAL, AND ACQUAINTANCE WITH THE

SUBJECT—EXAMPLES OF IMPERFECT TRANSFUSION

OF THE SENSE OF THE ORIGINAL—WHAT

OUGHT TO BE THE CONDUCT OF

A TRANSLATOR WHERE THE SENSE IS

AMBIGUOUS

In order that a translator may be enabled to

give a complete transcript of the ideas of the

original work, it is indispensably necessary,

that he should have a perfect knowledge of the

language of the original, and a competent

acquaintance with the subject of which it treats.

If he is deficient in either of these requisites, he

can never be certain of thoroughly comprehending

the sense of his author. M. Folard is allowed

to have been a great master of the art of war.

He undertook to translate Polybius, and to

give a commentary illustrating the ancient

Tactic, and the practice of the Greeks and

Romans in the attack and defence of fortified

places. In this commentary, he endeavours to[11]

shew, from the words of his author, and of other

ancient writers, that the Greek and Roman

engineers knew and practised almost every

operation known to the moderns; and that, in

particular, the mode of approach by parallels

and trenches, was perfectly familiar to them,

and in continual use. Unfortunately M. Folard

had but a very slender knowledge of the Greek

language, and was obliged to study his author

through the medium of a translation, executed

by a Benedictine monk,[7] who was entirely

ignorant of the art of war. M. Guischardt, a

great military genius, and a thorough master of

the Greek language, has shewn, that the work

of Folard contains many capital misrepresentations

of the sense of his author, in his account of

the most important battles and sieges, and has

demonstrated, that the complicated system

formed by this writer of the ancient art of war,

has no support from any of the ancient authors

fairly interpreted.[8]

The extreme difficulty of translating from the

works of the ancients, is most discernible to

those who are best acquainted with the ancient

languages. It is but a small part of the genius

and powers of a language which is to be learnt

from dictionaries and grammars. There are

innumerable niceties, not only of construction

and of idiom, but even in the signification of[12]

words, which are discovered only by much

reading, and critical attention.

A very learned author, and acute critic,[9] has,

in treating “of the causes of the differences in

languages,” remarked, that a principal difficulty

in the art of translating arises from this circumstance,

“that there are certain words in every

language which but imperfectly correspond to

any of the words of other languages.” Of this

kind, he observes, are most of the terms relating

to morals, to the passions, to matters of sentiment,

or to the objects of the reflex and internal

senses. Thus the Greek words αρετη, σωφροσυνη,

ελεος, have not their sense precisely and perfectly

conveyed by the Latin words virtus, temperantia,

misericordia, and still less by the English words,

virtue, temperance, mercy. The Latin word virtus

is frequently synonymous to valour, a sense

which it never bears in English. Temperantia,

in Latin, implies moderation in every desire,

and is defined by Cicero, Moderatio cupiditatum

rationi obediens.[10] The English word temperance,

in its ordinary use, is limited to moderation in

eating and drinking.

Observe

The rule of not too much, by Temperance taught,

In what thou eat’st and drink’st.

[13]

It is true, that Spenser has used the term in its

more extensive signification.

He calm’d his wrath with goodly temperance.

But no modern prose-writer authorises such

extension of its meaning.

The following passage is quoted by the

ingenious writer above mentioned, to shew, in

the strongest manner, the extreme difficulty of

apprehending the precise import of words of

this order in dead languages: “Ægritudo est

opinio recens mali præsentis, in quo demitti contrahique

animo rectum esse videatur. Ægritudini

subjiciuntur angor, mœror, dolor, luctus, ærumna,

afflictatio: angor est ægritudo premens, mœror

ægritudo flebilis, ærumna ægritudo laboriosa,

dolor ægritudo crucians, afflictatio ægritudo cum

vexatione corporis, luctus ægritudo ex ejus qui

carus fuerat, interitu acerbo.”[11]—“Let any one,”

says D’Alembert, “examine this passage with

attention, and say honestly, whether, if he had

not known of it, he would have had any idea of

those nice shades of signification here marked,

and whether he would not have been much

embarrassed, had he been writing a dictionary,

to distinguish, with accuracy, the words ægritudo,

mœror, dolor, angor, luctus, ærumna, afflictatio.”

The fragments of Varro, de Lingua Latina, the

treatises of Festus and of Nonius, the Origines

of Isidorus Hispalensis, the work of Ausonius[14]

Popma, de Differentiis Verborum, the Synonymes

of the Abbé Girard, and a short essay by Dr.

Hill[12] on “the utility of defining synonymous

terms,” will furnish numberless instances of those

very delicate shades of distinction in the signification

of words, which nothing but the most

intimate acquaintance with a language can teach;

but without the knowledge of which distinctions

in the original, and an equal power of discrimination

of the corresponding terms of his own

language, no translator can be said to possess

the primary requisites for the task he undertakes.

But a translator, thoroughly master of the

language, and competently acquainted with the

subject, may yet fail to give a complete transcript

of the ideas of his original author.

M. D’Alembert has favoured the public with

some admirable translations from Tacitus; and

it must be acknowledged, that he possessed every

qualification requisite for the task he undertook.

If, in the course of the following observations, I

may have occasion to criticise any part of his

writings, or those of other authors of equal

celebrity, I avail myself of the just sentiment of

M. Duclos, “On peut toujours relever les défauts

des grands hommes, et peut-être sont ils les seuls

qui en soient dignes, et dont la critique soit utile”

(Duclos, Pref. de l’Hist. de Louis XI.).

Tacitus, in describing the conduct of Piso

upon the death of Germanicus, says: Pisonem[15]

interim apud Coum insulam nuncius adsequitur,

excessisse Germanicum (Tacit. An. lib. 2, c. 75).

This passage is thus translated by M. D’Alembert,

“Pison apprend, dans l’isle de Cos, la mort

de Germanicus.” In translating this passage, it

is evident that M. D’Alembert has not given the

complete sense of the original. The sense of

Tacitus is, that Piso was overtaken on his voyage

homeward, at the Isle of Cos, by a messenger,

who informed him that Germanicus was dead.

According to the French translator, we understand

simply, that when Piso arrived at the Isle of

Cos, he was informed that Germanicus was dead.

We do not learn from this, that a messenger had

followed him on his voyage to bring him this

intelligence. The fact was, that Piso purposely

lingered on his voyage homeward, expecting this

very messenger who here overtook him. But,

by M. D’Alembert’s version it might be understood,

that Germanicus had died in the island of

Cos, and that Piso was informed of his death by

the islanders immediately on his arrival. The

passage is thus translated, with perfect precision,

by D’Ablancourt: “Cependant Pison apprend

la nouvelle de cette mort par un courier exprès,

qui l’atteignit en l’isle de Cos.”

After Piso had received intelligence of the

death of Germanicus, he deliberated whether to

proceed on his voyage to Rome, or to return

immediately to Syria, and there put himself at

the head of the legions. His son advised the[16]

former measure; but his friend Domitius Celer

argued warmly for his return to the province,

and urged, that all difficulties would give way to

him, if he had once the command of the army,

and had increased his force by new levies. At

si teneat exercitum, augeat vires, multa quæ provideri

non possunt in melius casura (An. l. 2, c.

77). This M. D’Alembert has translated, “Mais

que s’il savoit se rendre redoutable à la tête des

troupes, le hazard ameneroit des circonstances

heureuses et imprévues.” In the original passage,

Domitius advises Piso to adopt two distinct

measures; the first, to obtain the command of

the army, and the second, to increase his force by

new levies. These two distinct measures are

confounded together by the translator, nor is the

sense of either of them accurately given; for

from the expression, “se rendre redoutable à la

tête des troupes,” we may understand, that Piso

already had the command of the troops, and that

all that was requisite, was to render himself

formidable in that station, which he might do in

various other ways than by increasing the levies.

Tacitus, speaking of the means by which

Augustus obtained an absolute ascendency over

all ranks in the state, says, Cùm cæteri nobilium,

quanto quis servitio promptior, opibus et honoribus

extollerentur (An. l. 1, c. 2). This D’Alembert

has translated, “Le reste des nobles trouvoit

dans les richesses et dans les honneurs la récompense

de l’esclavage.” Here the translator has[17]

but half expressed the meaning of his author,

which is, that “the rest of the nobility were

exalted to riches and honours, in proportion as

Augustus found in them an aptitude and disposition

to servitude:” or, as it is well translated

by Mr. Murphy, “The leading men were

raised to wealth and honours, in proportion

to the alacrity with which they courted the

yoke.”[13]

Cicero, in a letter to the Proconsul Philippus

says, Quod si Romæ te vidissem, coramque gratias

egissem, quod tibi L. Egnatius familiarissimus

meus absens, L. Oppius præsens curæ fuisset.

This passage is thus translated by Mr. Melmoth:

“If I were in Rome, I should have waited upon

you for this purpose in person, and in order likewise

to make my acknowledgements to you for

your favours to my friends Egnatius and Oppius.”

Here the sense is not completely rendered, as

there is an omission of the meaning of the words

absens and præsens.

Where the sense of an author is doubtful, and

where more than one meaning can be given to

the same passage or expression, (which, by the

way, is always a defect in composition), the

translator is called upon to exercise his judgement,

and to select that meaning which is most

consonant to the train of thought in the whole[18]

passage, or to the author’s usual mode of thinking,

and of expressing himself. To imitate the

obscurity or ambiguity of the original, is a fault;

and it is still a greater, to give more than one

meaning, as D’Alembert has done in the beginning

of the Preface of Tacitus. The original runs

thus: Urbem Romam a principio Reges habuere.

Libertatem et consulatum L. Brutus instituit.

Dictaturæ ad tempus sumebantur: neque Decemviralis

potestas ultra biennium, neque Tribunorum

militum consulare jus diu valuit. The ambiguous

sentence is, Dictaturæ ad tempus sumebantur;

which may signify either “Dictators were chosen

for a limited time,” or “Dictators were chosen

on particular occasions or emergencies.” D’Alembert

saw this ambiguity; but how did he

remove the difficulty? Not by exercising his

judgement in determining between the two

different meanings, but by giving them both in

his translation. “On créoit au besoin des dictateurs

passagers.” Now, this double sense it was

impossible that Tacitus should ever have intended

to convey by the words ad tempus: and

between the two meanings of which the words

are susceptible, a very little critical judgement

was requisite to decide. I know not that ad

tempus is ever used in the sense of “for the

occasion, or emergency.” If this had been the

author’s meaning, he would probably have used

either the words ad occasionem, or pro re nata.

But even allowing the phrase to be susceptible[19]

of this meaning,[14] it is not the meaning which

Tacitus chose to give it in this passage. That

the author meant that the Dictator was created

for a limited time, is, I think, evident from the sentence

immediately following, which is connected

by the copulative neque with the preceding:

Dictaturæ ad tempus sumebantur: neque Decemviralis

potestas ultra biennium valuit: “The

office of Dictator was instituted for a limited

time: nor did the power of the Decemvirs subsist

beyond two years.”

M. D’Alembert’s translation of the concluding

sentence of this chapter is censurable on the

same account. Tacitus says, Sed veteris populi

Romani prospera vel adversa, claris scriptoribus

memorata sunt; temporibusque Augusti dicendis

non defuere decora ingenia, donec gliscente adulatione

deterrerentur. Tiberii, Caiique, et Claudii,

ac Neronis res, florentibus ipsis, ob metum falsæ:

postquam occiderant, recentibus odiis compositæ

sunt. Inde consilium mihi pauca de Augusto, et

extrema tradere: mox Tiberii principatum, et

cetera, sine ira et studio, quorum causas procul

habeo. Thus translated by D’Alembert: “Des

auteurs illustres ont fait connoitre la gloire et les

malheurs de l’ancienne république; l’histoire[20]

même d’Auguste a été écrite par de grands génies,

jusqu’aux tems ou la necessité de flatter les condamna

au silence. La crainte ménagea tant

qu’ils vécurent, Tibere, Caius, Claude, et Néron;

des qu’ils ne furent plus, la haine toute récente

les déchira. J’écrirai donc en peu de mots la fin

du regne d’Auguste, puis celui de Tibere, et les

suivans; sans fiel et sans bassesse: mon caractere

m’en éloigne, et les tems m’en dispensent.” In

the last part of this passage, the translator has

given two different meanings to the same clause,

sine ira et studio, quorum causas procul habeo, to

which the author certainly meant to annex only

one meaning; and that, as I think, a different

one from either of those expressed by the translator.

To be clearly understood, I must give my

own version of the whole passage. “The history

of the ancient republic of Rome, both in its

prosperous and in its adverse days, has been

recorded by eminent authors: Even the reign of

Augustus has been happily delineated, down to

those times when the prevailing spirit of adulation

put to silence every ingenuous writer. The

annals of Tiberius, of Caligula, of Claudius, and

of Nero, written while they were alive, were

falsified from terror; as were those histories

composed after their death, from hatred to their

recent memories. For this reason, I have resolved

to attempt a short delineation of the latter

part of the reign of Augustus; and afterwards

that of Tiberius, and of the succeeding princes;[21]

conscious of perfect impartiality, as, from the

remoteness of the events, I have no motive,

either of odium or adulation.” In the last clause

of this sentence, I believe I have given the true

version of sine ira et studio, quorum causas procul

habeo: But if this be the true meaning of the

author, M. D’Alembert has given two different

meanings to the same sentence, and neither of

them the true one: “sans fiel et sans bassesse:

mon caractere m’en éloigne, et les tems m’en

dispensent.” According to the French translator,

the historian pays a compliment first to his own

character, and secondly, to the character of the

times; both of which he makes the pledges of

his impartiality: but it is perfectly clear that

Tacitus neither meant the one compliment nor

the other; but intended simply to say, that the

remoteness of the events which he proposed to

record, precluded every motive either of unfavourable

prejudice or of adulation.

[22]

CHAPTER III

WHETHER IT IS ALLOWABLE FOR A TRANSLATOR

TO ADD TO OR RETRENCH THE IDEAS

OF THE ORIGINAL.—EXAMPLES OF THE USE

AND ABUSE OF THIS LIBERTY

If it is necessary that a translator should give

a complete transcript of the ideas of the original

work, it becomes a question, whether it is allowable

in any case to add to the ideas of the

original what may appear to give greater force

or illustration; or to take from them what may

seem to weaken them from redundancy. To

give a general answer to this question, I would

say, that this liberty may be used, but with

the greatest caution. It must be further observed,

that the superadded idea shall have the

most necessary connection with the original

thought, and actually increase its force. And,

on the other hand, that whenever an idea is cut

off by the translator, it must be only such as is

an accessory, and not a principal in the clause

or sentence. It must likewise be confessedly

redundant, so that its retrenchment shall not

impair or weaken the original thought. Under

these limitations, a translator may exercise his

judgement, and assume to himself, in so far,

the character of an original writer.

[23]

It will be allowed, that in the following instance

the translator, the elegant Vincent Bourne,

has added a very beautiful idea, which, while it

has a most natural connection with the original

thought, greatly heightens its energy and tenderness.

The two following stanzas are a part

of the fine ballad of Colin and Lucy, by Tickell.

To-morrow in the church to wed,

Impatient both prepare;

But know, fond maid, and know, false man,

That Lucy will be there.

There bear my corse, ye comrades, bear,

The bridegroom blithe to meet,

He in his wedding-trim so gay,

I in my winding-sheet.

Thus translated by Bourne:

Jungere cras dextræ dextram properatis uterque,

Et tardè interea creditis ire diem.

Credula quin virgo, juvenis quin perfide, uterque

Scite, quod et pacti Lucia testis erit.

Exangue, oh! illuc, comites, deferte cadaver,

Qua semel, oh! iterum congrediamur, ait;

Vestibus ornatus sponsalibus ille, caputque

Ipsa sepulchrali vincta, pedesque stolâ.

In this translation, which is altogether excellent,

it is evident, that there is one most

beautiful idea superadded by Bourne, in the line

Qua semel, oh! &c.; which wonderfully improves

upon the original thought. In the original, the[24]

speaker, deeply impressed with the sense of her

wrongs, has no other idea than to overwhelm

her perjured lover with remorse at the moment

of his approaching nuptials. In the translation,

amidst this prevalent idea, the speaker all at

once gives way to an involuntary burst of tenderness

and affection, “Oh, let us meet once

more, and for the last time!” Semel, oh! iterum

congrediamur, ait.—It was only a man of exquisite

feeling, who was capable of thus improving

on so fine an original.[15]

Achilles (in the first book of the Iliad), won

by the persuasion of Minerva, resolves, though

indignantly, to give up Briseis, and Patroclus is

commanded to deliver her to the heralds of

Agamemnon:

Ως φατο· Πατροκλος δε φιλω επεπεἰθεθ’ εταιρω·

Εκ δ’ ἄγαγε κλισιης Βρισηιδα καλλιπαρηον,

Δῶκε δ’ αγειν· τω δ’ αυτις ιτην παρα νηας Αχαιων·

Ἡ δ’ αεκουσ’ ἁμα τοισι γυνὴ κιεν.

“Thus he spoke. But Patroclus was obedient to

his dear friend. He brought out the beautiful

Briseis from the tent, and gave her to be carried

away. They returned to the ships of the

Greeks; but she unwillingly went, along with

her attendants.”

[25]

Patroclus now th’ unwilling Beauty brought;

She in soft sorrows, and in pensive thought,

Past silent, as the heralds held her hand,

And oft look’d back, slow moving o’er the strand.

The ideas contained in the three last lines are

not indeed expressed in the original, but they

are implied in the word αεκουσα; for she who

goes unwillingly, will move slowly, and oft look

back. The amplification highly improves the

effect of the picture. It may be incidentally

remarked, that the pause in the third line, Past

silent, is admirably characteristic of the slow and

hesitating motion which it describes.

In the poetical version of the 137th Psalm, by

Arthur Johnston, a composition of classical

elegance, there are several examples of ideas

superadded by the translator, intimately connected

with the original thoughts, and greatly

heightening their energy and beauty.

Urbe procul Solymæ, fusi Babylonis ad undas

Flevimus, et lachrymæ fluminis instar erant:

Sacra Sion toties animo totiesque recursans,

Materiem lachrymis præbuit usque novis.

Desuetas saliceta lyras, et muta ferebant

Nablia, servili non temeranda manu.

Qui patria exegit, patriam qui subruit, hostis

Pendula captivos sumere plectra jubet:

Imperat et lætos, mediis in fletibus, hymnos,

Quosque Sion cecinit, nunc taciturna! modos.

Ergone pacta Deo peregrinæ barbita genti

Fas erit, et sacras prostituisse lyras?

[26]

Ante meo, Solyme, quam tu de pectore cedas,

Nesciat Hebræam tangere dextra chelyn.

Te nisi tollat ovans unam super omnia, lingua

Faucibus hærescat sidere tacta meis.

Ne tibi noxa recens, scelerum Deus ultor! Idumes

Excidat, et Solymis perniciosa dies:

Vertite, clamabant, fundo jam vertite templum,

Tectaque montanis jam habitanda feris.

Te quoque pœna manet, Babylon! quibus astra lacessis

Culmina mox fient, quod premis, æqua solo:

Felicem, qui clade pari data damna rependet,

Et feret ultrices in tua tecta faces!

Felicem, quisquis scopulis illidet acutis

Dulcia materno pignora rapta sinu!

I pass over the superadded idea in the second

line, lachrymæ fluminis instar erant, because,

bordering on the hyperbole, it derogates, in some

degree, from the chaste simplicity of the original.

To the simple fact, “We hanged our harps on

the willows in the midst thereof,” which is most

poetically conveyed by Desuetas saliceta lyras, et

muta ferebant nablia, is superadded all the

force of sentiment in that beautiful expression,

which so strongly paints the mixed emotions of

a proud mind under the influence of poignant

grief, heightened by shame, servili non temeranda

manu. So likewise in the following stanza there

is the noblest improvement of the sense of the

original.

Imperat et lætos, mediis in fletibus, hymnos,

Quosque Sion cecinit, nunc taciturna! modos.

The reflection on the melancholy silence that[27]

now reigned on that sacred hill, “once vocal

with their songs,” is an additional thought, the

force of which is better felt than it can be

conveyed by words.

An ordinary translator sinks under the energy

of his original: the man of genius frequently

rises above it. Horace, arraigning the abuse of

riches, makes the plain and honest Ofellus thus remonstrate

with a wealthy Epicure (Sat. 2, b. 2).

Cur eget indignus quisquam te divite?

A question to the energy of which it was not

easy to add, but which has received the most

spirited improvement from Mr. Pope:

How dar’st thou let one worthy man be poor?

An improvement is sometimes very happily

made, by substituting figure and metaphor to

simple sentiment; as in the following example,

from Mr. Mason’s excellent translation of Du

Fresnoy’s Art of Painting. In the original,

the poet, treating of the merits of the antique

statues, says:

queis posterior nil protulit ætas

Condignum, et non inferius longè, arte modoque.

This is a simple fact, in the perusal of which

the reader is struck with nothing else but the

truth of the assertion. Mark how in the translation

the same truth is conveyed in one of the

finest figures of poetry:

[28]

with reluctant gaze

To these the genius of succeeding days

Looks dazzled up, and, as their glories spread,

Hides in his mantle his diminish’d head.

In the two following lines, Horace inculcates

a striking moral truth; but the figure in which

it is conveyed has nothing of dignity:

Pallida mors æquo pulsat pede pauperum tabernas

Regumque turres.

Malherbe has given to the same sentiment a

high portion of tenderness, and even sublimity:

Le pauvre en sa cabane, où le chaume le couvre,

Est sujet à ses loix;

Et la garde qui veille aux barrieres du Louvre,

N’en défend pas nos rois.

[16]

Cicero writes thus to Trebatius, Ep. ad fam.

lib. 7, ep. 17: Tanquam enim syngrapham ad

Imperatorem, non epistolam attulisses, sic pecuniâ

ablatâ domum redire properabas: nec tibi in

mentem veniebat, eos ipsos qui cum syngraphis

venissent Alexandriam, nullum adhuc nummum

auferre potuisse. The passage is thus translated

by Melmoth, b. 2, l. 12: “One would have

imagined indeed, you had carried a bill of

exchange upon Cæsar, instead of a letter of

recommendation: As you seemed to think you[29]

had nothing more to do, than to receive your

money, and to hasten home again. But money,

my friend, is not so easily acquired; and I

could name some of our acquaintance, who have

been obliged to travel as far as Alexandria in

pursuit of it, without having yet been able to

obtain even their just demands.” The expressions,

“money, my friend, is not so easily

acquired,” and “I could name some of our

acquaintance,” are not to be found in the

original; but they have an obvious connection

with the ideas of the original: they increase

their force, while, at the same time, they give

ease and spirit to the whole passage.

I question much if a licence so unbounded

as the following is justifiable, on the principle

of giving either ease or spirit to the original.

In Lucian’s Dialogue Timon, Gnathonides,

after being beaten by Timon, says to him,

Αει φιλοσκῴμμων συ γε· αλλα ποῦ το συμποσιον;

ὡς καινον τι σοι ασμα των νεοδιδακτων διθυραμβων ἥκω

κομιζων.

“You were always fond of a joke—but where

is the banquet? for I have brought you a new

dithyrambic song, which I have lately learned.”

In Dryden’s Lucian, “translated by several

eminent hands,” this passage is thus translated:

“Ah! Lord, Sir, I see you keep up your old

merry humour still; you love dearly to rally

and break a jest. Well, but have you got a[30]

noble supper for us, and plenty of delicious

inspiring claret? Hark ye, Timon, I’ve got a

virgin-song for ye, just new composed, and

smells of the gamut: ’Twill make your heart

dance within you, old boy. A very pretty she-player,

I vow to Gad, that I have an interest in,

taught it me this morning.”

There is both ease and spirit in this translation;

but the licence which the translator has

assumed, of superadding to the ideas of the

original, is beyond all bounds.

An equal degree of judgement is requisite

when the translator assumes the liberty of

retrenching the ideas of the original.

After the fatal horse had been admitted within

the walls of Troy, Virgil thus describes the

coming on of that night which was to witness

the destruction of the city:

Vertitur interea cœlum, et ruit oceano nox,

Involvens umbrâ magnâ terramque polumque,

Myrmidonumque dolos.

The principal effect attributed to the night

in this description, and certainly the most

interesting, is its concealment of the treachery

of the Greeks. Add to this, the beauty which

the picture acquires from this association of

natural with moral effects. How inexcusable

then must Mr. Dryden appear, who, in his

translation, has suppressed the Myrmidonumque

dolos altogether?

[31]

Mean time the rapid heav’ns roll’d down the light,

And on the shaded ocean rush’d the night:

Our men secure, &c.

Ogilby, with less of the spirit of poetry, has

done more justice to the original:

Meanwhile night rose from sea, whose spreading shade

Hides heaven and earth, and plots the Grecians laid.

Mr. Pope, in his translation of the Iliad, has,

in the parting scene between Hector and Andromache

(vi. 466), omitted a particular respecting

the dress of the nurse, which he thought an

impropriety in the picture. Homer says,

Αψ δ’ ὁ παϊς προς κολπον ἐϋζωνοιο τιθηνης

Εκλινθη ἰαχων.

“The boy crying, threw himself back into the

arms of his nurse, whose waist was elegantly

girt.” Mr. Pope, who has suppressed the

epithet descriptive of the waist, has incurred on

that account the censure of Mr. Melmoth, who

says, “He has not touched the picture with that

delicacy of pencil which graces the original, as

he has entirely lost the beauty of one of the

figures.—Though the hero and his son were designed

to draw our principal attention, Homer

intended likewise that we should cast a glance

towards the nurse” (Fitzosborne’s Letters, l. 43).

If this was Homer’s intention, he has, in my

opinion, shewn less good taste in this instance[32]

than his translator, who has, I think with much

propriety, left out the compliment to the nurse’s

waist altogether. And this liberty of the translator

was perfectly allowable; for Homer’s

epithets are often nothing more than mere

expletives, or additional designations of his persons.

They are always, it is true, significant of

some principal attribute of the person; but they

are often applied by the poet in circumstances

where the mention of that attribute is quite

preposterous. It would shew very little judgement

in a translator, who should honour Patroclus

with the epithet of godlike, while he is

blowing the fire to roast an ox; or bestow on

Agamemnon the designation of King of many

nations, while he is helping Ajax to a large

piece of the chine.

It were to be wished that Mr. Melmoth, who

is certainly one of the best of the English

translators, had always been equally scrupulous

in retrenching the ideas of his author. Cicero

thus superscribes one of his letters: M. T. C.

Terentiæ, et Pater suavissimæ filiæ Tulliolæ,

Cicero matri et sorori S. D. (Ep. Fam. l. 14, ep.

18). And another in this manner: Tullius

Terentiæ, et Pater Tulliolæ, duabus animis suis,

et Cicero Matri optimæ, suavissimæ sorori (lib.

14, ep. 14). Why are these addresses entirely

sunk in the translation, and a naked title poorly

substituted for them, “To Terentia and Tullia,”

and “To the same”? The addresses to these[33]

letters give them their highest value, as they

mark the warmth of the author’s heart, and the

strength of his conjugal and paternal affections.

In one of Pliny’s Epistles, speaking of Regulus,

he says, Ut ipse mihi dixerit quum consuleret,

quam citò sestertium sexcenties impleturus esset,

invenisse se exta duplicata, quibus portendi millies

et ducenties habiturum (Plin. Ep. l. 2, ep. 20).

Thus translated by Melmoth, “That he once

told me, upon consulting the omens, to know

how soon he should be worth sixty millions of

sesterces, he found them so favourable to him

as to portend that he should possess double

that sum.” Here a material part of the original

idea is omitted; no less than that very circumstance

upon which the omen turned, viz.,

that the entrails of the victim were double.

Analogous to this liberty of adding to or

retrenching from the ideas of the original, is the

liberty which a translator may take of correcting

what appears to him a careless or inaccurate

expression of the original, where that inaccuracy

seems materially to affect the sense. Tacitus

says, when Tiberius was entreated to take upon

him the government of the empire, Ille variè

disserebat, de magnitudine imperii, suâ modestiâ

(An. l. 1, c. 11). Here the word modestiâ is

improperly applied. The author could not

mean to say, that Tiberius discoursed to the

people about his own modesty. He wished

that his discourse should seem to proceed from[34]

modesty; but he did not talk to them about his

modesty. D’Alembert saw this impropriety,

and he has therefore well translated the passage:

“Il répondit par des discours généraux sur son

peu de talent, et sur la grandeur de l’empire.”

A similar impropriety, not indeed affecting

the sense, but offending against the dignity of

the narrative, occurs in that passage where

Tacitus relates, that Augustus, in the decline

of life, after the death of Drusus, appointed his

son Germanicus to the command of eight legions

on the Rhine, At, hercule, Germanicum Druso

ortum octo apud Rhenum legionibus imposuit

(An. l. 1, c. 3). There was no occasion here for

the historian swearing; and though, to render

the passage with strict fidelity, an English

translator must have said, “Augustus, Egad,

gave Germanicus the son of Drusus the command

of eight legions on the Rhine,” we cannot

hesitate to say, that the simple fact is better

announced without such embellishment.

[35]

CHAPTER IV

OF THE FREEDOM ALLOWED IN POETICAL

TRANSLATION.—PROGRESS OF POETICAL

TRANSLATION IN ENGLAND.—B. JONSON,

HOLIDAY, SANDYS, FANSHAW, DRYDEN.—ROSCOMMON’S

ESSAY ON TRANSLATED

VERSE.—POPE’S HOMER.

In the preceding chapter, in treating of the

liberty assumed by translators, of adding to, or

retrenching from the ideas of the original, several

examples have been given, where that liberty

has been assumed with propriety both in prose

composition and in poetry. In the latter, it is

more peculiarly allowable. “I conceive it,” says

Sir John Denham, “a vulgar error in translating

poets, to affect being fidus interpres. Let that

care be with them who deal in matters of fact or

matters of faith; but whosoever aims at it in

poetry, as he attempts what is not required, so

shall he never perform what he attempts; for it is

not his business alone to translate language into

language, but poesie into poesie; and poesie is of

so subtle a spirit, that in pouring out of one

language into another, it will all evaporate; and

if a new spirit is not added in the transfusion,

there will remain nothing but a caput mortuum”

(Denham’s Preface to the second book of Virgil’s

Æneid).

[36]

In poetical translation, the English writers of

the 16th, and the greatest part of the 17th

century, seem to have had no other care than

(in Denham’s phrase) to translate language into

language, and to have placed their whole merit

in presenting a literal and servile transcript of

their original.

Ben Jonson, in his translation of Horace’s

Art of Poetry, has paid no attention to the

judicious precept of the very poem he was

translating:

Nec verbum verbo curabis reddere, fidus

Interpres.

Witness the following specimens, which will

strongly illustrate Denham’s judicious observations.

Mortalia facta peribunt;

Nedum sermonum stet honos et gratia vivax.

Multa renascentur quæ jam cecidere, cadentque

Quæ nunc sunt in honore vocabula, si volet usus,

Quem penes arbitrium est et jus et norma loquendi.

All mortal deeds

Shall perish; so far off it is the state

Or grace of speech should hope a lasting date.

Much phrase that now is dead shall be reviv’d,

And much shall die that now is nobly liv’d,

If custom please, at whose disposing will

The power and rule of speaking resteth still.

[37]

Interdum tamen et vocem Comœdia tollit,

Iratusque Chremes tumido delitigat ore,

Et Tragicus plerumque dolet sermone pedestri.

Telephus et Peleus, cùm pauper et exul uterque,

Projicit ampullas et sesquipedalia verba,

Si curat cor spectantis tetigisse querela.

Yet sometime doth the Comedy excite,

Her voice, and angry Chremes chafes outright,

With swelling throat, and oft the tragic wight

Complains in humble phrase. Both Telephus

And Peleus, if they seek to heart-strike us,

That are spectators, with their misery,

When they are poor and banish’d must throw by

Their bombard-phrase, and foot-and-half-foot words.

So, in B. Jonson’s translations from the Odes

and Epodes of Horace, besides the most servile

adherence to the words, even the measure of the

original is imitated.

Non me Lucrina juverint conchylia,

Magisve rhombus, aut scari,

Si quos Eois intonata fluctibus

Hyems ad hoc vertat mare:

Non Afra avis descendat in ventrem meum,

Non attagen Ionicus

Jucundior, quam lecta de pinguissimis

Oliva ramis arborum;

Aut herba lapathi prata amantis, et gravi

Malvæ salubres corpori.

Not Lucrine oysters I could then more prize,

Nor turbot, nor bright golden eyes;

[38]

If with east floods the winter troubled much

Into our seas send any such:

The Ionian god-wit, nor the ginny-hen

Could not go down my belly then

More sweet than olives that new-gathered be,

From fattest branches of the tree,

Or the herb sorrel that loves meadows still,

Or mallows loosing bodies ill.

Of the same character for rigid fidelity, is the

translation of Juvenal by Holiday, a writer of

great learning, and even of critical acuteness, as

the excellent commentary on his author fully

shews.

Omnibus in terris quæ sunt a Gadibus usque

Auroram et Gangem, pauci dignoscere possunt

Vera bona, atque illis multum diversa, remotâ

Erroris nebulâ. Quid enim ratione timemus,

Aut cupimus? quid tam dextro pede concipis, ut te

Conatûs non pœniteat, votique peracti.

Evertêre domos totas optantibus ipsis

Dii faciles.

In all the world which between Cadiz lies

And eastern Ganges, few there are so wise

To know true good from feign’d, without all mist

Of Error. For by Reason’s rule what is’t

We fear or wish? What is’t we e’er begun

With foot so right, but we dislik’d it done?

Whole houses th’ easie gods have overthrown

At their fond prayers that did the houses own.

There were, however, even in that age, some

writers who manifested a better taste in poetical[39]

translation. May, in his translation of Lucan’s

Pharsalia, and Sandys, in his Metamorphoses of

Ovid, while they strictly adhered to the sense of

their authors, and generally rendered line for line,

have given to their versions both an ease of

expression and a harmony of numbers, which

approach them very near to original composition.

The reason is, they have disdained to confine

themselves to a literal interpretation, but have

everywhere adapted their expression to the

idiom of the language in which they wrote.

The following passage will give no unfavourable

idea of the style and manner of May. In

the ninth book of the Pharsalia, Cæsar, when in

Asia, is led from curiosity to visit the plain of

Troy:

Here fruitless trees, old oaks with putrefy’d

And sapless roots, the Trojan houses hide,

And temples of their Gods: all Troy’s o’erspread

With bushes thick, her ruines ruined.

He sees the bridall grove Anchises lodg’d;

Hesione’s rock; the cave where Paris judg’d;

Where nymph Oenone play’d; the place so fam’d

For Ganymedes’ rape; each stone is nam’d.

A little gliding stream, which Xanthus was,

Unknown he past, and in the lofty grass

Securely trode; a Phrygian straight forbid

Him tread on Hector’s dust! (with ruins hid,

The stone retain’d no sacred memory.)

Respect you not great Hector’s tomb, quoth he!

—O great and sacred work of poesy,

That free’st from fate, and giv’st eternity

To mortal wights! But, Cæsar, envy not

Their living names, if Roman Muses aught

[40]

May promise thee, while Homer’s honoured

By future times, shall thou, and I, be read:

No age shall us with darke oblivion staine,

But our Pharsalia ever shall remain.

Jam silvæ steriles, et putres robore trunci

Assaraci pressere domos, et templa deorum

Jam lassa radice tenent; ac tota teguntur

Pergama dumetis; etiam periere ruinæ.

Aspicit Hesiones scopulos, silvasque latentes

Anchisæ thalamos; quo judex sederit antro;

Unde puer raptus cœlo; quo vertice Nais

Luserit Oenone: nullum est sine nomine saxum.

Inscius in sicco serpentem pulvere rivum

Transierat, qui Xanthus erat; securus in alto

Gramine ponebat gressus: Phryx incola manes

Hectoreos calcare vetat: discussa jacebant

Saxa, nec ullius faciem servantia sacri:

Hectoreas, monstrator ait, non respicis aras?

O sacer, et magnus vatum labor; omnia fato

Eripis, et populis donas mortalibus ævum!

Invidia sacræ, Cæsar, ne tangere famæ:

Nam siquid Latiis fas est promittere Musis,

Quantum Smyrnei durabunt vatis honores,

Venturi me teque legent: Pharsalia nostra

Vivet, et a nullo tenebris damnabitur ævo.

Independently of the excellence of the above

translation, in completely conveying the sense,

the force, and spirit of the original, it possesses

one beauty which the more modern English

poets have entirely neglected, or rather purposely

banished from their versification in rhyme; I

mean the varied harmony of the measure, which

arises from changing the place of the pauses.[41]

In the modern heroic rhyme, the pause is almost

invariably found at the end of a couplet. In the

older poetry, the sense is continued from one

couplet to another, and closes in various parts

of the line, according to the poet’s choice, and

the completion of his meaning:

A little gliding stream, which Xanthus was,

Unknown he past—and in the lofty grass

Securely trode—a Phrygian straight forbid

Him tread on Hector’s dust—with ruins hid,

The stone retain’d no sacred memory.

He must be greatly deficient in a musical ear,

who does not prefer the varied harmony of the

above lines to the uniform return of sound, and

chiming measure of the following:

Here all that does of Xanthus stream remain,

Creeps a small brook along the dusty plain.

While careless and securely on they pass,

The Phrygian guide forbids to press the grass;

This place, he said, for ever sacred keep,

For here the sacred bones of Hector sleep:

Then warns him to observe, where rudely cast,

Disjointed stones lay broken and defac’d.

Yet the Pharsalia by Rowe is, on the whole,

one of the best of the modern translations of the

classics. Though sometimes diffuse and paraphrastical,

it is in general faithful to the sense of

the original; the language is animated, the verse

correct and melodious; and when we consider

the extent of the work, it is not unjustly[42]

characterised by Dr. Johnson, as “one of the

greatest productions of English poetry.”

Of similar character to the versification of

May, though sometimes more harsh in its

structure, is the poetry of Sandys:

There’s no Alcyone! none, none! she died

Together with her Ceÿx. Silent be

All sounds of comfort. These, these eyes did see

My shipwrack’t Lord. I knew him; and my hands

Thrust forth t’ have held him: but no mortal bands

Could force his stay. A ghost! yet manifest,

My husband’s ghost: which, Oh, but ill express’d

His forme and beautie, late divinely rare!

Now pale and naked, with yet dropping haire:

Here stood the miserable! in this place:

Here, here! (and sought his aërie steps to trace).

Nulla est Alcyone, nulla est, ait: occidit una

Cum Ceyce suo; solantia tollite verba:

Naufragus interiit; vidi agnovique, manusque

Ad discedentem, cupiens retinere, tetendi.

Umbra fuit: sed et umbra tamen manifesta, virique

Vera mei: non ille quidem, si quæris, habebat

Assuetos vultus, nec quo prius ore nitebat.

Pallentem, nudumque, et adhuc humente capillo,

Infelix vidi: stetit hoc miserabilis ipso

Ecce loco: (et quærit vestigia siqua supersint).

In the above example, the solantia tollite

verba is translated with peculiar felicity, “Silent

be all sounds of comfort;” as are these words,

Nec quo prius ore nitebat, “Which, oh! but ill

express’d his forme and beautie.” “No mortal

bands could force his stay,” has no strictly corresponding[43]

sentiment in the original. It is a

happy amplification; which shews that Sandys

knew what freedom was allowed to a poetical

translator, and could avail himself of it.

From the time of Sandys, who published his

translation of the Metamorphoses of Ovid in

1626, there does not appear to have been much

improvement in the art of translating poetry till

the age of Dryden:[17] for though Sir John Denham

has thought proper to pay a high compliment

to Fanshaw on his translation of the

Pastor Fido, terming him the inventor of “a

new and nobler way”[18] of translation, we find

nothing in that performance which should intitle

it to more praise than the Metamorphoses by

Sandys, and the Pharsalia by May.[19]

[44]

But it was to Dryden that poetical translation

owed a complete emancipation from her fetters;

and exulting in her new liberty, the danger now

was, that she should run into the extreme of

licentiousness. The followers of Dryden saw[45]

nothing so much to be emulated in his translations

as the ease of his poetry: Fidelity was but

a secondary object, and translation for a while

was considered as synonymous with paraphrase.

A judicious spirit of criticism was now wanting

to prescribe bounds to this increasing licence,

and to determine to what precise degree a

poetical translator might assume to himself the

character of an original writer. In that design,

Roscommon wrote his Essay on Translated

Verse; in which, in general, he has shewn

great critical judgement; but proceeding, as all

reformers, with rigour, he has, amidst many

excellent precepts on the subject, laid down one

rule, which every true poet (and such only

should attempt to translate a poet) must consider

as a very prejudicial restraint. After

judiciously recommending to the translator, first

to possess himself of the sense and meaning of

his author, and then to imitate his manner and

style, he thus prescribes a general rule,

Your author always will the best advise;

Fall when he falls, and when he rises, rise.

Far from adopting the former part of this

maxim, I conceive it to be the duty of a poetical

translator, never to suffer his original to fall.

He must maintain with him a perpetual contest

of genius; he must attend him in his highest

flights, and soar, if he can, beyond him: and

when he perceives, at any time, a diminution of[46]

his powers, when he sees a drooping wing, he

must raise him on his own pinions.[20] Homer

has been judged by the best critics to fall at

times beneath himself, and to offend, by introducing

low images and puerile allusions. Yet

how admirably is this defect veiled over, or

altogether removed, by his translator Pope. In

the beginning of the eighth book of the Iliad,

Jupiter is introduced in great majesty, calling a

council of the gods, and giving them a solemn

charge to observe a strict neutrality between the

Greeks and Trojans:

Ἠὼς μεν κροκόπεπλος ἐκιδνατο πᾶσαν ἐπ’ αίαν·

Ζευς δε θεῶν ἀγορην ποιησατο τερπικέραυνος,

Ἀκροτάτη κορυφη πολυδειραδος Οὐλυμποιο·

Αὐτὸς δέ σφ’ ἀγόρευε, θεοὶ δ’ ἅμα πάντες ἄκουον·

“Aurora with her saffron robe had spread returning[47]

light upon the world, when Jove delighting-in-thunder

summoned a council of the gods

upon the highest point of the many-headed

Olympus; and while he thus harangued, all the

immortals listened with deep attention.” This

is a very solemn opening; but the expectation of

the reader is miserably disappointed by the

harangue itself, of which I shall give a literal

translation.

Κέκλυτέ μευ, πάντες τε θεοὶ, πᾶσαὶ τε θέαιναι,

Ὄφρ’ εἴπω, τά με θυμὸς ἐνὶ στήθεσσι κελεύει·

Μήτε τις οὖν θήλεια θεὸς τόγε, μήτε τις ἄρσην

Πειράτω διακέρσαι ἐμὸν ἔπος· ἀλλ’ ἅμα πάντες

Αἰνεῖτ’, ὄφρα τάχιστα τελευτήσω τάδε ἔργα.

Ον δ’ ἂν ἐγὼν ἀπάνευθε θεῶν ἐθέλοντα νοήσω

Ἐλθόντ, ἢ Τρώεσσιν ἀρηγέμεν, ἢ Δαναοῖσι,

Πληγεὶς οὐ κατα κόσμον ἐλευσεται Οὔλυμπόνδε·

Η μιν ἑλὼν ῥίψω ἐς Τάρταρον ἠερόεντα,

Τῆλε μάλ’, ἦχι βάθιστον ὑπο χθονός ἐστι βέρεθρον,

Ἔνθα σιδήρειαί τε πύλαι καὶ χάλκεος οὐδὸς,

Τόσσον ἔνερθ’ Ἀΐδεω, ὅσον οὐρανός ἐστ’ ἀπὸ γαίης·

Γνώσετ’ ἔπειθ’, ὅσον εἰμὶ θεῶν κάρτιστος ἁπάντων.

Εἴ δ’ ἄγε, πειρήσασθε θεοὶ, ἵνα εἴδετε πάντες,

Σειρην χρυσείην ἐξ οὐρανόθεν κρεμάσαντες·

Πάντες δ’ ἐξάπτεσθε θεοὶ, πᾶσαί τε θέαιναι·

Ἀλλ’ οὐκ ἂν ἐρύσαιτ’ ἐξ οὐρανόθεν πεδίονδε

Ζῆν’ ὕπατον μήστωρ’ οὐδ’ εἰ μάλα πολλὰ κάμοιτε.

Ἀλλ’ ὅτε δὴ καὶ ἐγὼ πρόφρων ἐθέλοιμι ἐρύσσαι,

Αὐτῆ κεν γάιῃ ἐρύσαιμ’, αὐτῆ τε θαλάσσῃ·

Σειρην μέν κεν ἔπειτα περὶ ῥίον Οὐλύμποιο

Δησαίμην· τὰ δέ κ’ αὖτε μετήορα πάντα γένοιτο·

Τόσσον ἐγώ περί τ’ εἰμὶ θεῶν, περί τ’ εἴμ’ ἀνθρώπων.

“Hear me, all ye gods and goddesses, whilst I

declare to you the dictates of my inmost heart.[48]

Let neither male nor female of the gods attempt

to controvert what I shall say; but let all submissively

assent, that I may speedily accomplish

my undertakings: for whoever of you shall be

found withdrawing to give aid either to the

Trojans or Greeks, shall return to Olympus

marked with dishonourable wounds; or else I

will seize him and hurl him down to gloomy

Tartarus, where there is a deep dungeon under

the earth, with gates of iron, and a threshold

of brass, as far below hell, as the earth is below

the heavens. Then he will know how

much stronger I am than all the other gods.

But come now, and make trial, that ye may all

be convinced. Suspend a golden chain from

heaven, and hang all by one end of it, with your

whole weight, gods and goddesses together:

you will never pull down from the heaven to the

earth, Jupiter, the supreme counsellor, though

you should strain with your utmost force. But

when I chuse to pull, I will raise you all, with

the earth and sea together, and fastening the

chain to the top of Olympus, will keep you all

suspended at it. So much am I superior both

to gods and men.”

It must be owned, that this speech is far

beneath the dignity of the Thunderer; that

the braggart vaunting in the beginning of it

is nauseous; and that a mean and ludicrous

picture is presented, by the whole group of

gods and goddesses pulling at one end of[49]

a chain, and Jupiter at the other. To veil

these defects in a translation was difficult;[21] but

to give any degree of dignity to this speech

required certainly most uncommon powers.

Yet I am much mistaken, if Mr. Pope has

not done so. I shall take the passage from

the beginning:

Aurora now, fair daughter of the dawn,

Sprinkled with rosy light the dewy lawn,