This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: A Fool in Spots

Author: Hallie Erminie Rives

Release Date: April 7, 2021 [eBook #65018]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A FOOL IN SPOTS***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/foolinspots00riveiala |

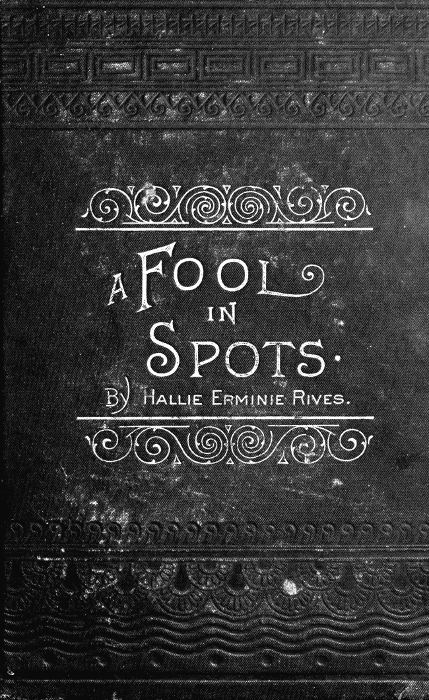

“‘She is beautiful!’ he exclaimed.” Page 77.

BY

HALLIE ERMINIE RIVES.

————

ILLUSTRATED.

————

PUBLISHED BY

Woodward & Tiernan Printing Co.

St. Louis.

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1894, by

Woodward & Tiernan Printing Company,

st. louis, mo.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

| Page | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| Two Artists | 7 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| Dreams and Schemes | 20 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| An Honest Man’s Honest Love | 31 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| In the Social Realm | 37 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| The Image of Beautiful Sin | 44 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| White Roses | 52 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| The Call of a Soul | 57 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| Life’s Night Watch | 62 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| A Kentucky Stock Farm | 68 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| The Birth Mark | 75 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| Hearts Laid Bare | 87 | |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| Sunlight | 97 | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| The Picturesque Sport | 103 | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| Wedded | 108 | |

| CHAPTER XV. | ||

| Chloral | 113 | |

| [Pg 6]CHAPTER XVI. | ||

| A Bold Intruder | 120 | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | ||

| An Errand of Mystery | 130 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | ||

| A Timely Warning | 140 | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | ||

| A Plaint of Pain | 146 | |

| CHAPTER XX. | ||

| A Crop of Kisses | 151 | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | ||

| A Hope of Change | 156 | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | ||

| The Home in the South | 160 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | ||

| A Strange Departure | 172 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | ||

| Of the World, Unworldly | 183 | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | ||

| Tempted | 193 | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | ||

| Lost Faith | 197 | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | ||

| The Cup of Wrath and Trembling | 203 | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | ||

| A Drop of Poison | 207 | |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | ||

| Robert’s Triumph | 211 | |

| CHAPTER XXX. | ||

| Shadowing Her | 216 | |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | ||

| Gone | 219 | |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | ||

| Storming the Lion’s Den | 222 | |

| Conclusion | 232 | |

They were seated tete-a-tete at a dinner table.

“Tell me why you have never married, Milburn,” and the steel eyes in Willard Frost’s face searched through his glasses.

Robert Milburn’s answer was a shrug, and a long cloud of smoke blown back at the glowing end of his cigar.

“Tell me why,” persisted the keen-eyed Frost.

“Because it is too expensive a luxury; besides, a man who has affianced a career like mine must take that for his bride,” was Robert’s answer.

“Admitting there is warmth and color in some of your artistic creations, old fellow, I should think you would find these scarcely available of winter nights, eh?”

Robert laughed; his laugh was short, though, and bitter. He had taken keen pleasure in the cynical[Pg 8] worldly wisdom and unsentimental judgment of this man.

“If you can’t afford the wife, then let the wife afford you,” began Frost’s logical reasoning. “You have brain, muscle and youth. Marry them to that necessary adjunct which you do not possess, and which the government refuses to supply. This is perfectly practical. The whole question of marriage is too much a matter of sentiment; too little a matter of judgment. Now, the son of a millionaire without an idea above his raiment and his club, devoid of morals and of brains, marries the daughter of a silver king. What is the result? A race of vulgar imbeciles.”

Here Frost, more wickedly practical, continued: “Now, you are of gentle blood, being fitted out by nature with the most unfortunate combination of attributes. Nature has given you much more than your share of intelligence and manly beauty, together with most refined and sympathetic sensibilities and luxurious tastes, and then has placed you in an orbit representing intelligence, aristocracy and wealth. Here she has left you to revolve with the greater and lesser luminaries, and that with the slenderest of incomes, which is not as yet greatly increased by your profession. You doubtless find that it requires considerable [Pg 9]financiering to do these things deemed necessary to maintain your position in the constellation.”

“It is rather annoying to be poor,” Robert answered in a carefully repressed voice. A hard sigh followed, and there flashed through him the hot consciousness of the bitter truth. For that special reason no word had ever crossed his lips that could, by any means, be twisted into serious suit with the fair sex. It was generally accepted that he was not a “marrying” man.

They were, both of them, men who would at first sight interest a stranger. The younger of the two you might have seen before if you frequented the ultra-fashionable dinner parties, luncheons, etc., of polite New York. Anywhere, everywhere, was Robert Milburn a special guest and a general favorite.

He was medium-sized, delicately featured, with a look of half-lazy enthusiasm. You would set him down at once as an artistic character; at the same time, there was in his make-up and bearing, that which bespeaks an ambitious nature. His companion, who appeared older, was a man of statelier stamp, tall and sufficiently athletic. His face was well finished and had a certain air of self-possession, which not a few name self-conceit, and resent accordingly.

“Ah! Robert, you have entirely too much sentiment, my boy. Do not waste yourself. I will cite you a girl—there’s Frances Baxter. True, she is not good looking, in fact, I presume quite a few consider her extraordinarily plain. But that excessive income is worth your while to aspire to—such a name as Milburn is certainly worth something.”

With an earnestness of tone and manner which the gossipy nature of the talk hardly seemed to call for, Robert nervously threw aside his crumpled napkin and looked sharply at his companion, saying:

“Surely, then, I may do something better with it than sell it.”

“There, we will not argue, I am too wise to oppose a man who is laboring under the temporary insanity of a love affair. I had feared that you were not so level-headed as is your wont. Come, who is the woman? Is it the Southern girl at the Stanhope’s?”

“Of whom do you speak?” asked Robert, looking pale and annoyed.

“Of Miss Bell—Cherokee Bell—to be sure.”

“You honor me with superior judgment to so accuse, whether it be true or not,” and upon Milburn’s face there was that expression which tells of what is beyond.

The other smiled meaningly, and raised his brows.

“Ah, my dear boy,” he mutely commented, “I am sorry my supposition is true, but it leaves me wiser, and no transparent scheming goes.”

“Tell me your opinion of her, Milburn, I am interested deeply.”

“Well, I have always said she was positively refreshing,” began Robert. “She came upon us to recall a bright world. She came as a revelation to some, a reminiscence to others, and caused our social Sahara to blossom with a suddenly enriched oasis.”

“Yes, she has that indescribable lissomeness and grace which she doubtless inherits with her Southern blood. I was attracted, too, by the delicacy of her hands and feet, of which she is pardonably proud. But that scar or something disfigures one hand.”

Robert spoke up quickly: “That is a birth-mark, I think it is a fern leaf.”

“A birth-mark! Oh hopelessly plebeian, don’t you think?”

“Your Miss Baxter has a very vivid one upon her neck.”

“I beg pardon, then, birthmarks are just the thing.”

Frost had commenced in a bantering mood, but now and again his voice would take a more serious tone.

“Joking apart, Miss Bell is charming. She is, thanks to God, a being out of the ordinary. She has a style unstinted and all her own. I have upon several occasions made myself agreeable, partly for my own gratification and partly because I saw in her eyes that she admired me.”

Frost leaned back in intended mock conceit, no small portion of which appeared genuine.

Robert gave way to laughter, in which just a tinge of annoyance might have been detected.

“She is quite accustomed to these attentions, for all her life adoration has been her daily bread.”

“I should like to know how you are so well posted?” asked Frost, with a dark flash in his grey eyes.

Robert Milburn lifted his head proudly, and answered quietly: “I have known her since she was a little slip of a lass.”

“And how did the meeting come about? you were brought up in Maryland, I believe.”

“True, but in the early ’80s I spent one spring and summer South. I was at ‘Ashland.’ You know that is the old home of Henry Clay. It is about in the center of the region of blue grass,[Pg 13] down in Kentucky. Clay’s great grandson, by marriage, Major McDowell, owns this historic place. He is a well-mannered and distinguished host, and allowed me to fancy myself an artist then, and I made some sketches of his horses—he is a celebrated stock breeder.”

“How I should enjoy seeing a good stock farm; that is one pleasure I am still on this side of,” put in Willard. “Go on, I meant not to interrupt you.”

“The Major often saddled two of his fine steppers and invited me to ride over the country with him. It was upon one of these jaunts that I met the girl. It happened in this way: We were in the blue grass valley just this side of the mountainous region. A turn-row, running through a field of broken sod was our route, to avoid a dangerous creek ford. With heartsome calls and chirruping, six plowmen went up and down the long rows. The light earth, creaming away from the bright plowshare, heaped upon their bare feet. I thought, ‘What is so delicious as the feel of it—yielding, cool, electrical, fresh.’ We stopped to watch them. They tramped sturdily behind the mules, one hand upon the plow-handle, the other wrapped about with the line that ran to the beast’s head. Presently, they all fell to singing a song—a relic, it must have been, from the[Pg 14] old care-free days. Over and over they chanted the rude lilt, and their voices were mildly sweet. We stopped to listen, for their song was like no other melodies under the sun.”

“But where does the girl come in? I expected to hear something of her,” interrupted Willard, with an impatient gesture.

“Oh, yes! She is just down a trifle farther in the pasture lands with an ‘ole Auntie.’ The Major addressed the negress as ‘Aunt Judy.’ They were welcoming the new comer—a calf. The Auntie wore a bandana and a coarse cotton print, over which was a thin, diamond-shaped shawl. Her subdued face was brown—the brown of tobacco—and her weary eyes stole quick, wondering glances at us, and instinctively she took the child’s hand, as if to be sure she was safe.

“Now I come to Cherokee—let me try to describe her to you. In coloring, delicacy, freshness, she was a flower. Her hair was combed straight back, but it was perversely curly; and the short hairs around her forehead had a fashion of falling loosely about, which was very pretty. She was slim, her drooping-lashed eyes wore a soft seriousness. She at once chained my vagrant fancy and I promised myself that would not be the only time I should look upon her. On the homeward way the Major[Pg 15] told me she was the only child of Darwin Bell, an excellent man. A man of good blood, good sense and piety, ‘but the best of all,’ continued the Major, ‘he was a gallant Confederate captain.’

“Then he happened to recall the fact that I was of the other side and said: ‘I beg your pardon young man, but Darwin and I were army mates, and that eulogy was but a heart-throb.’

“He had quite a little to tell of the negress. She was Cherokee’s ‘black mammy,’ and her faithfulness was a striking illustration of the devotion of the slaves. It seems to me that the most callous man or woman could not fail to appreciate little touches, here and there, of the sweet kindly feeling that nestles close to the core of honest human hearts. I went home that night in a softer mood.”

“Softer in more senses than one, I judge, also poorer,” Frost returned, amusedly.

“You mean I had lost my heart?” the other asked in an odd tone.

“To be sure, but tell me more of Miss Bell, she is very like a serial story, and I want awfully to read the next chapters.”

“Then you must learn the sequel from her.”

“That is not quite fair of you, but I have a mind to; in fact, I know I cannot resist cultivating your blonde amaryllis, if you don’t object?”

Willard Frost smiled half—chaffingly, and quite enjoyed the expression of surprise and anxiety upon his companion’s face.

“That is a matter of the utmost indifference to me,” was the icy answer. The speaker’s hand, as it lay on the table, opened and shut in a quick nervous fashion, which showed that he was more annoyed than he looked, whereupon Frost waxed more eloquent and earnest.

“I mean to enter, though well I know, when love is a game of three, one heart can win but pain.”

“But that would surely be mine, for what chance has a poor devil of an artist like me with the invincible Frost?”

“I come under the same heading,” returned Willard, “I am an artist too.”

“Yes, but it would keep me in a desperate rush to run ahead of you—you the prince of the swagger set, a member of half a dozen clubs, owner of the smartest of four-in-hands, a capital dinner-giver, and a first-rate host, and, accompanying these, a plethoric purse to make all hospitalities easy.”

As Robert spoke, Frost poured out the last of the second bottle of champagne and looked carelessly at the bill for it, which the waiter had presented to the other.

“Suppose you find you a champion to do your battle—a John Alden?”

“He might do as Alden did, and keep the prize. My chum, Latham, is the only one I dare trust to win and divide spoils, and he is abroad now, you know.”

“Right glad I am, for Marrion Latham is a marvellous success with womankind. Still, I want some one to oppose me, for no game is worth a rap for a rational man to play unless he has competition”—this with decided emphasis.

“What’s the matter with Fred Stanhope? I think he will make it interesting for you.”

“Oh, I want a man, not a sissy. He is just the son of Mr. Stanhope. He hasn’t enough sense to grease gimlets. He is a rich-born freak, and I think he has set out to make a condign idiot of himself, in the briefest, directest manner, and he will doubtless succeed. I prefer you for a rival.”

“But Frost, I would be powerless, quite powerless, with you in the field.”

“Ah, you idealize me, make me too great a hero,” answered Frost, quite pleased within himself.

“Not a hero,” spoke Robert slowly, “but a smooth calculating man of the period, just the manner of man to take with that type of woman.[Pg 18] She, this charming, intense creature, is so innocent, so ‘un-woke-up’, I might say.”

“I am a holy terror at awakening one, and if there is any money with it I shall exert myself to arouse her.”

There was an awkward silence. Frost paused and lighted a cigarette.

“Has she any plantations, stock farms, and the like? You seem so well up in her history.”

“No, with the exception of a thousand dollars or so, she is absolutely without means.”

“That settles it,” said Frost, flippantly. “You and your John Alden may open negotiations for her beauty and innocence, but they are too tame for me.”

“You are a fisherman, Frost, and if you can’t catch a whale you catch a trout, and if you can’t catch a trout you would whip in the shallows for the poor little minnows.”

“Minnows have their use as bait,” returned the other, with a meaning smile.

“But not to catch whales with, and you direct the training of my harpoon toward a big haul, yet you can stop to fish where you get but a nibble? What a peculiar adviser—rather inconsistent, don’t you think?” observed Robert, with a cynical sense of amusement. “I shall keep an eye on you.”

“And I shall keep an eye on that fact,” muttered Frost to himself when he had left his friend. “It is not much, but it would answer the small demands of an honest girl. I will see about that thousand dollars.”

Willard Frost’s observations rang in Robert Milburn’s ear, not without effect, as he walked to his room that evening, albeit, his conscience refuted the arguments. He whiled away an hour or more piecing together the broken threads of their discussion. Frost had said, and in truth, that Miss Baxter was the richest prize of the season. She had turned all heads with her fabulous wealth. He had said, “A union of wealth and genius is as it should be.” That speech had a mild influence over Robert. There was something very soothing and agreeable to be called a rising genius, and, then, the thought that other men would be gnashing their teeth was a stimulant to his vanity.

Miss Baxter was a sharp girl, and she had an exquisite figure which she dressed with the best of taste. What if her nose was a trifle snub, and her mouth verging on the coarse, she had a large capital to contribute to a copartnership.

But when love, or whatever else by a less pretty name we may call the emotion which stirs within[Pg 21] us, responsive to the glance or touch of a woman, sweeps man’s nature as the harpist the strings of his harp, all thoughts pass under the dominion of the master passion; even the thought of self, with all its impudent assertiveness, changes its accustomed force, and sinks to a secondary place.

Love is a disturber and routs philosophy, and as for matrimony, Robert rather agreed with the philosopher who said, “You will regret it whether you marry or not.” An old painter had once told him that in bringing too much comfort and luxury into the home of the artist, it frightened inspiration.

“Art,” he said, “needs either solitude, poverty or passion; too warm an atmosphere suffocates it. It is a mountain wind-flower that blooms fairest in a sterile soil.”

From the scene-house of Robert’s memory came visions strangely sweet; they came like the lapse of fading lesson days, gemmed here and there with joys, and crimsoned all over with the silken suppleness of youth and its delights.

Again the glamour of gold and green lay over the warm South earth. New leaves danced out in the early sunshine, dripping sweet odors upon all below. Robins in full song made vocal the budding hedgerows from under which peeped the hasty gold of the crocus flower. By fence and field peach trees[Pg 22] up-flushed in rosy growth, and the wild plum’s scented snowing made all the days afaint and fair. And again the woods were brave in summer greenery; hawthorn—dogwood, stood bridal all in white.

Matted honeysuckle, that opened as if by magic in the dewless, stirless night, arched above a garden gate, wherefrom, with hasty thrift, tall lilacs framed a girl in wreathen bloom.

From the moment the gleam of that sweet face of hers touched him, the world, he felt, would lose its luster if Cherokee did not smile on him, and him alone, of all the world of men.

All the wealth, fashion and talent of the rest of women in their totality, were of no more meaning to him than the floating of motes in the great sunbeam of his love for this girl. This fact made all other resolutions impossible—glaringly impossible.

With this honest conviction in his manly breast he went to bed, and the blessed visitor of peace placed fingers upon his eyelids to keep watch until the morrow.

* * * * * *

Two ladies, in loose but becoming morning gowns, sat, at the fashionable hour of eleven, breakfasting in a dainty boudoir in an extension to a fine [Pg 23]residence on Fifth Avenue. The table, a low square table covered with whitest linen, was set before a great open fireplace, where gas gave forth flashes of lurid lights which were refracted by the highly polished surface of the silver tray, teapot, sugar and creamer.

The elder lady had the morning paper in her lap and she sat sipping her tea. She scarcely looked her four and forty. Youth was past, but the charm of gracious maturity lay in her clear glance and about the soft smiling mouth. The girl had turned her easy chair away from the table, perching her pretty feet on the brass rail of the fender. Her aristocratic brown-blonde head was bending over the Herald.

“Here is another puff about Willard Frost, the portrait painter,” she said complacently. “He has become the rage; I suppose the fact that he is a romantic figure of an unconventional type is one reason as well as his artistic qualities.”

“‘He has become the rage.’” Page 23.

“And, too, because he is unmarried,” said the elderly lady. “Society is strange, and when the gods marry they lose caste. If he should bring home one day a beautiful wife, I fancy few women would care about sitting for portraits then.”

“I cannot understand that; why is it?” inquired the girl, innocently.

“Because women declare against women. I wouldn’t be surprised if they were already angry with you.”

“Why?”

“I have thought that he fancied you and showed you preference.”

“He has been quite nice, but I thought it was generally understood that he would make love to Miss Baxter.”

“I may be wrong, but I sometimes imagine you like him, and I do not blame you either, my dear; many a girl has married less attractive men than your artist.”

“Oh, he is handsome, has a magnificent build, and that voice—” murmured the girl, clasping her hands over her knee and looking into the fire.

The other watched her intently and said slowly: “I had hoped to save you for my boy—he is our best gift from God, and you—come next.”

The girl smiled softly, “Oh, Fred doesn’t care for me; he says I remind him of hay fields and yielding clover. I take it that he means I am too ‘fresh,’” observed the girl, half seriously.

“Not at all; what is purer and sweeter than to be forest-bred? Why, after all these long years, I tire of my city fostering and long for the South country where your mother and I grew into [Pg 25]womanhood. And while Fred chaffs you about being a country girl, he is really proud of you. He often talks to me: ‘Why, mother,’ he tells me, ‘I never saw anything like it; as soon as she appeared she shone; a sudden brightness fills the place wherever she goes; a softened splendor comes around.’ And dear, I am not blind, I see you are besieged by smiles and light whispered loves—you hold all hearts in that sweet thrall; you are the bright flame in which many moths burn.”

“You are both very, very, kind—Fred and you”—Here she was interrupted by a maid entering with a card.

“Mr. Willard Frost.”

“Ah, Cherokee, what did I tell you? He has even taken the liberty of calling at unconventional hours.”

As Frost waited below he nervously moved about; there was a sort of sub-conscious discomfort, as of one whose clothes are a misfit. The least sound added to his uneasy feeling.

“Am I actually in love with her?” he asked, “or does her maidenly and becoming coyness excite my surfeited passion? Is it something that will burn off at a touch, like a lighted sedge-field,” he reflected. “Would I marry her if I could? Well, what’s the difference? The part I have undertaken[Pg 26] is a good one; I will see it through and risk the winning.”

When Cherokee appeared he thought her lovelier than ever. He looked hungrily at her fair, high-bred face, her enigmatical smile that might mean so much or so little. She gave him her hand in kindly welcome.

“You will pardon my stupidity to-day, for I shouldn’t have come feeling so badly, and I should not have come at all had I not wanted a kind word of sympathy,” he said, when the first salutations were received.

“You did quite right,” she answered, “burdens shared are easier carried. What is your trouble?”

“I would not confide in many, but somehow I have always felt we were vastly more than common friends. Do you feel that way about it?” he asked, in weighing tones.

“I take great delight in your companionship,” she told him, frankly.

“And it is these subtle, intelligent sympathies which make you most dangerously charming. Now, I have a question; do not answer me if you think it wrong of me to ask, but did you ever like a man so well that you fancied yourself married to him?”

She laughed a care-free, girlish laugh.

“Why no, now that you ask, I’m sure I never did.”

Then there was a long, uncomfortable pause, broken by saying: “Ah, well, there’s time enough, only be sure that you know your heart, if you have any; have you?”

She laughed again her gay little laugh. “I’ll tell him that if he ever comes.”

He had a far-away look, and breathed long and deeply. Suddenly he spoke up.

“Dearest love,” taking both her hands and looking with gravity into her face, “I did not mean to say it yet, but I must. I love you—I love you—and I would show it in a thousand ways. Be my wife.”

She listened to each word intently, her face neither flushed nor paled. She spoke very deliberately: “I—your wife, Mr. Frost? No. You interest me, but if I care for you, there is something that mars its fullness. Forgive me for saying it plainly, but I do not love you.”

“But, little woman, you cannot but awaken to it sometime. It is a heart of stone that will not warm to the touch of such love as mine. Love is dependent upon contact; we are only the wires through which the current throbs—lifeless before they are touched, and listless when sundered.”

He attempted to take her in his arms, but she slipped from his embrace, and naively replied, “If[Pg 28] that’s your theory, there’s one remedy: I’ll break your circuit.”

“Was there ever such a tangle of weakness and strength in woman?” he asked himself. He bit his lips and marvelled; he had again been thwarted. Pretty soon he leaned heavily on the table, and looked the embodiment of despair.

“What makes you so gloomy?” asked Cherokee, sweetly.

“Because I am a lost and ruined man. I never felt quite so alone and friendless.”

“Why friendless? Tell me what it is that makes you so downhearted?” Her tones were well calculated to reassure him.

“I am suffering from the inevitable misery which, as a ghost, follows the erring,” he said, and his voice was hard.

“Tell me all about it, Mr. Frost, that I may be in sympathy with you.”

“Then I will tell you all,” raising a face that looked worn and worried. “There is nothing of sentiment in my misfortune; as rascally old Panurge used to put it, ‘I am troubled with a disease known as a plentiful lack of money.’”

“Why, Mr. Frost, I thought you were rich; the world takes it that way.”

“I did possess a fair competency until two weeks[Pg 29] ago, but an unfortunate investment in Reading swept it away like thistledown in the wind. The friends to whom I could apply for aid are in the same boat. For one of them, I, very like the fool Antonio, have gone security for a thousand dollars. To-morrow that must be paid else I lose my pound of flesh, which, taken literally, means my studio, pictures, and, worst of all, my reputation.”

“And you call yourself a fool for helping a friend; I am surprised at that.”

“You are right. I shouldn’t feel that way, for he is noble beyond the common; his faults, such as they are, have been more hurtful to himself than to others.” Frost spoke magnanimously.

“Who is the friend?” she asked, so impulsively that it bore no trace of impertinence.

“Pardon me, but I would not mention his name; however, you know him quite well.”

Cherokee turned her face full upon him and asked bravely: “Will you let me help you both?”

He appeared startled: “You little woman, you! What on earth could you do but be grieved at a friend’s misfortune?” She little knew that all this was but to abuse that intense, fond, clinging sympathy.

“I have fourteen hundred in my own name, will you use part of that?”

“Great heavens, no. I would become a beggar first!”

“But if I insist, and it will save you and—him?”

Willard Frost sat for a time without speaking; apparently he was weighing some profound subject. At last he looked up and gathered Cherokee’s hands in his.

“I appreciate the spirit that prompts you to make this heroic offer to me. When will you need this money?”

“Not for two months yet, I expect to spend the winter in ‘Frisco’ with Mr. and Mrs. Stanhope.”

“Are you absolutely in earnest about our using it?”

“Never was more in earnest in my lifetime,” she answered, solemnly.

“Then I will take it, though I feel humbled to the very dust to think of these little hands saving me.”

He bent and kissed them as reverently as though she had been his patron saint. As she gave him the check for one thousand dollars, Cherokee thought his trembling hands told, but too well, of humbled pride.

“That was a stroke of genius—a decided stroke of genius,” he said to himself, as he passed into the club house that day.

It was far into twilight when Robert Milburn rang the bell at the Stanhopes. He had called to escort them to the closing ball of the Manhattan season.

“I have not seen you for more than a week, Robert. I fear you have been worrying or working too hard,” said Cherokee, looking at him searchingly and anxiously.

“Ah, not working any more than I should, yet there has been a terrible weight on my mind—a crushing weight.”

“Then, let us remain at home to-night; I prefer it.”

“You must have read my mind, I wanted so much to stay, but the fear of cheating you of pleasure kept me from suggesting it.”

So it was agreed upon that they would not go to the ball.

“Now tell me what makes you overtax your strength?” said Cherokee, sweetly and solicitously.

“I must get on in my profession, so that one day you will be proud of me.” His enthusiasm inspired her.

“I am that already, and shall never cease to hope for you and be proud of your many successes. A great future is waiting to claim you, Mr. Milburn.”

“Not unless that future’s arm can hold both of us, Cherokee, for you are still all I really want praise from—all I fear in the blaming. But, sweetheart, you have dropped me as a child throws away a toy when it is weary. When Frost told me he had been here it started afresh some thoughts that I find lurking about my mind so often of late.”

Did her bowed head mean an effort to hide a face that told too much?

“I believe you are sorry he is not with you here now.”

She laid her hand in playful reproach upon his lips. “Sorry, you foolish boy! I am glad you are here, isn’t that enough?”

“I hope so; forgive me, Cherokee, but you do not know the world. It is deeper, darker, wider, than you have ever dreamed, and there are some very queer people in it. I shall keep my eyes open, and if I can help it, you shall never know it as I do.”

“Why, what harm can come to me? What could the world have against me?” and her innocent face looked hurt.

“Nothing, except your beauty and purity, and either is a dangerous charge. I wish you could[Pg 33] have always lived among the bees and bloomings, with the South country folk.”

“Why, do you find it annoying to have me near?”

“No, but very annoying to have you near others I know. I cannot quite understand some men—for instance, Willard Frost.”

“I think he is a very warm friend of yours.”

“Probably so, probably so. But, Cherokee, tell me, in truth, do you love him?”

“I do not,” she answered, promptly, and there was nothing in her eyes but truth.

“My God,” Robert cried within him, “you have been merciful. Cherokee, listen to me—I know you already understand what I am about to say: You have known from the first that you are the greatest of what there is in my life. There is no joy through all the day but that it brings with it a desire to share it with you. I often awake with your half-spoken name on my lips, as though, when I slipped through the portals of unconsciousness into the world of reality, I came only to find you, as a frightened child awakes and calls feebly for its mother. I look to your love for the sweetness of home. I need you; can you say ‘We need each other?’”

The adoration he expressed for her filled her with innocent wonder and gratitude. His overpowering[Pg 34] love and worship for her startled her by its force into a sweet shame, a hesitating fear. She was looking at him with her eyes softly opening and closing, like the eyes of a startled doe, as though the wonder and delight were too great to be taken in at once.

At length she made answer, hesitatingly, “And—this—beautiful—love—is—for—me?”

“It is all for you,” he said, tenderly.

“Robert, there is a feeling for you which I think is a part of my soul, but I do not know that it is love. It came to me—this feeling—so long ago that I believe that it has a seven-years’ claim. It was far back yonder, when I played at “camping out” under the broad white tents that the dogwoods pitched in the forest. I spent hours and hours in my play making clover chains to reach from my heart to yours—”

Here he interrupted her. “And it did reach me, finding fertile soil in which to grow. Tell me you have kept your part alive.”

“I cannot tell yet, I am going to test it. I believe I will imagine you feeling the morning kiss of Miss Baxter, and watching her good-night smile, and see if I would care.”

“Please do, but tell me why you said Miss Baxter? Why not any other lady of my acquaintance?”

“I suppose it is because I often hear that you are awfully fond of her.”

“That is not true, my dearest. I like her for the reason she thinks worlds of Marrion Latham, the dramatist. By the way, I had such a good letter from him to-day, so full of wonderful sympathy and friendship. I have often told him of you. I love that fellow. He knew I loved you before you did, I guess. You know, men in their friendships are trustful, they impose great confidences in each other, and are frank and outspoken. Even the solid, practical outside world recognizes the bonds of such faith, and looks with contempt upon the man who, having parted with his friend, reveals secrets which have been told him under the sacred profession of friendship.”

“Why is it, Robert, that women cannot be true, or a man and woman cannot form a lasting, loyal friendship?”

“The first case, jealousy or envy breaks; the second generally ends in one falling in love with the other, and that spoils it,” he explained.

She looked up archly: “Which will be the most enduring, your friendship for Marrion, or your love for me?”

“Please God that both shall last always,” he answered, with reverence.

“How good it seems to hear you say that.” Then she impulsively held out her hands saying: “I do care.”

Robert, trembling from head to foot at the mad audacity of his act, bent down to taste from the calyx of that flower-face the sweet intoxication of the first kiss. The worried look had gone out of his face.

“The sweet intoxication of the first kiss.” Page 36.

“So you will wait for me until I have made a name that will grace you! How brave of you to make me that promise. Cherokee are you all mine? Then there are only two more things required in this—the sanction of the State, and the blessing of God. May He keep a watch over both our lives.”

“I pray that your wish be granted,” she murmured, with a tender voice.

“Now, my little woman, be very careful of the people you meet. Unfortunately, one forgets sometimes when one is in danger. You are a woman, sweet, passionate and kind; just the favorite prey.”

She looked at him intently, as if endeavoring to divine his underlying thoughts.

“What do you mean, sweetheart?”

He knew by the tremor in her voice she was hurt.

“I mean, dear, that lions are admitted into the fold because they are tame lions—look out for them.”

The next moment he was gone.

Carriages, formed in double ranks by the police, lined the pavement of several blocks on —— street, and from them alighted, as each carriage made a brief stop at the entrance, men and women of fashion, enveloped in heavy wraps, for the night was cold. Beneath the heavy opera coats, sealskins, etc., ball dresses were visible, and feet encased in fur-lined boots caught the eyes of those who stood watching the guests of the —— ball as they entered the building.

Music filled the vast dance-hall. High up in the galleries musicians were stationed, who toiled away at their instruments, furnishing enlivening strains of waltzes or polkas for the dancers. To the right, adown corridors of arched gold, the reception rooms were filled with metropolitan butterflies.

The scene was an interesting study. Foremost of all could be noticed the voluptuous freedom of manner, though the picturesque grace of the leading lights was never wholly lost. They were [Pg 38]dissolute, but not coarse; bold, but not vulgar. They took their pleasure in a delicately wanton way, which was infinitely more dangerous in its influence than would have been gross mirth or broad jesting. Rude licentiousness has its escape-valve in disgust, but the soft sensualism of a cultured aristocrat is a moral poison, the effects of which are so insidious as to be scarcely felt until all the native nobility is almost withered.

It is but justice to them to say, there was nothing repulsive in the mischievous merriment of these revelers; their witticisms were brilliant and pointed, but never indelicate. Some of the dancers, foot-weary, lounged gracefully about, and the attendant slaves were often called upon to refill the wine glasses.

In every social gathering, as in a garden, or in the heavens, there is invariably one particular and acknowledged flower, or star. Here all eyes followed the beautiful, spirited, inspiring girl, who was under the chaperonage of Mrs. Stanhope. This fresh, beaming girl, unspoiled by flattery, remained naive, affectionate and guileless.

During the changing of groups and pairs, this girl heard the sweet, languid voice of Willard Frost. Through the clatter of other men it came like the silver stroke of a bell in a storm at sea. She[Pg 39] flushed radiantly as he and Miss Baxter joined her party.

“Ah, my dear Miss Bell, you are looking charming,” he exclaimed, effusively. He took her hand, a little soft pink one, that looked like a shell uncurled.

“Come, honor Miss Baxter and me by taking just one glass of sherry,” and he called a passing waiter.

Cherokee looked at him with startled surprise. “How often, Mr. Frost, will I have a chance to decline your offers like this? I tell you again, I have never taken wine, and I congratulate myself.”

“Are you to be congratulated or condoled with?” There was irony in Miss Baxter’s tone, though her laugh was good natured, as she continued, “I see you are yet a beautiful alien, for a glass of good wine, or an occasional cigarette is never out of place with us. All of these nervous fads are city equipments.”

“Then, if not to smoke and not to drink are country virtues, pray introduce them into city life,” was Cherokee’s answer.

“Ah, no indeed, I would never take the liberty of reversing the order of things, for they just suit me,” and Miss Baxter’s bright eyes twinkled under drooping lashes. As she smiled she raised[Pg 40] a glass of wine to her lips, kissed the brim, and gave it to Willard Frost with an indescribably graceful swaying gesture of her whole form.

“Here’s to your pastoral sweetheart, the sorceress, sovereign of the South.”

“‘Here’s to your pastoral sweetheart, the sorceress, sovereign of the South.’” Page 40.

He seized the glass eagerly, drank, and returned it with a profound salutation.

The consummate worldlings were surprised to hear Miss Bell answer:

“Thank you, but how much more appropriate would be, ‘Here’s to a Fool in Spots!’”

Willard replied, with a shake of the head:

“Ah, no, you have too much ‘snap’ to be called a fool in any sense, besides, you only need being disciplined—you’ll be enjoying life by and by. When I first met our friend Milburn he was saying the same thing, but where is he now?——”

Here Miss Baxter laid her pretty jeweled hand warningly upon his arm.

“Come, you would not be guilty of divulging such a delicious secret, would you?”

He treated the matter mostly as a joke, and returned with a tantalizing touch in his speech:

“Robert didn’t mean to do it. We must forgive.”

Cherokee looked puzzled as she caught the exchange of significant smiles. She spoke, as always, in her own soft, syllabled tongue.

“What do you mean, may I ask?”

Willard Frost coughed, and took her fan with affectionate solicitude.

“It may not be just fair to answer your question. I am sorry.”

“Mr. Milburn is a friend of mine, and if anything has happened to him why shouldn’t I know it?” she inquired, somewhat tremulously.

No combination of letters can hope to convey an idea of the music of her rare utterance of her sweetheart’s name.

“But you wouldn’t like him better for the knowing,” he interrupted. “Besides, he will come out all right if he follows my instructions implicitly.”

She stared blankly at him, vainly trying to comprehend what he meant. Then there came an anxious look on her face, such a look as people wear when they wish to ask something of great moment, but dare not begin. At last she summoned up courage.

“Mr. Frost,” she said, in a weak, low voice, “he—Robert—hasn’t done anything wrong?”

“Wrong, what do you call wrong?” was the laconic question, “but I trust the matter is not so serious as it appears.”

“Ah, I am so foolish,” and she smiled gently.

“No, it is well enough to have a friend’s interest at heart, and you won’t cut him off if you hear it—you are not that sort. I know you are clever and thoughtful, and all that, but you possess the forgiving spirit. Now, unlike some men, I judge people gently, don’t come down on other men’s failings. Who are we, any of us, that we should be hard on others?”

“Judge gently,” she replied.

“I hope I always do that.”

“If I only dared tell her now,” said Frost to himself, “but it’s not my affair.”

He saw the feminine droop of her head, and the dainty curve of her beautiful arm.

“She is about to weep,” he muttered.

Miss Baxter, who had been amusing herself with other revelers, turned to interrupt: “Mr. Frost, you haven’t given him dead away?”

This, so recklessly spoken, only added to Cherokee’s discomfort. A flush rose to her cheek. She asked, with partial scorn:

“Do you think he should have aroused my interest without satisfying it?”

“Please forgive him, he didn’t intend to be so rude; besides, he would have told you had I not interrupted. It was thoughtless of you to make mention of it,” she said, reproachfully, to the artist.

The while he seemed oddly enjoying the girl’s strange dry-eyed sorrow.

Just here, Fred Stanhope came up to tell them the evening pleasures were done. Cherokee could have told him that sometime before.

Willard Frost looked remarkably bright and handsome as he walked away with Miss Baxter leaning upon his arm.

“What made you punish that poor girl so? What pleasure was there in giving Mr. Milburn away, especially since you were the entire cause of it?” she went on earnestly, and a trifle dramatically. “A man has no right to give another away—no right—he should——”

“But Frances,” remonstrated Frost, lightly, and apparently unimpressed by her theory, “I was just dying to tell her that Milburn was as drunk as a duchess.”

In his fashionable apartments, Willard Frost walked back and forth in his loose dressing-gown. Rustling about the room, his softly slippered feet making no noise on the floor, he moved like a refined tiger—looked like “some enchanted marquis of the impenitently wicked sort, in story, whose periodical change into tiger from man was either just going off or just coming on.”

A good opportunity for consideration, surrounded by the advantages of solitude. He moved from end to end of his voluptuous room, looking now and again at a picture which hung just above a Persian couch, covered with a half dozen embroidered pillows.

What unmanageable thoughts ran riot in his head, as he surveyed the superb image and thought that only one thing was wanting—the breath of life—for which he had waited through all these months.

For two heavy hours he walked and thought; now he would heave a long, low sigh, then hold his breath again.

When at last he dropped down upon his soft bed, he lay and wondered if the world would go his way—the way of his love for a woman.

* * * * * *

Cherokee met Willard Frost on Broadway the next morning—he had started to see her.

“Let me go back with you and we will lunch together—what do you say?” he proposed.

“Very well, for I am positively worn out to begin with the day, and a rest with you will refresh me,” she said sweetly.

They took the first car down town and went to a café for lunch. Willard laughed mischievously as he glanced down the wine list on the menu card.

“What will you have to-day?”

“What I usually take,” she answered, in the same playful mood.

“I received that perplexing note of yours, but don’t quite interpret it,” he began, taking it from his pocket and reading:

‘Dear Mr. Frost:

I am anxious to sit for the picture at once. Of course you will never speak of it. Don’t let anyone know it.

Yours, in confidence,

Cherokee.’

“It is very plain,” she pouted. “Don’t you remember I had told you I was going to have my portrait made for Mrs. Stanhope on her birthday. That doesn’t come just yet, in fact it is three months off, but you know we are going to ‘Frisco’ for the winter, and there isn’t much time to lose; I have been busy two months making preparations.”

“What! Are you going, too? I was thinking a foolish thought,” he sighed. “I was thinking maybe you would remain here while they were away.”

“Not for anything; I have been planning and looking forward to this trip a whole year.” She seemed perfectly elated at the thought.

“There is nothing to induce you to remain?”

“Nothing,” she answered, with emphasis.

“I have an aunt with whom you could stay, and we could learn much of each other. Do stay,” he insisted.

“I must go, though I shall not forget you in the ‘winter of our content.’”

“That’s very kind, I am sure, but I have set my heart on seeing you during the entire season, for Milburn, poor boy, is so hard at work he will not intrude upon my time often. Besides, he is getting careless of late—doesn’t want society. The fact is, I believe he is profoundly discouraged. This work of art is a slow and tedious one. But he keeps on[Pg 47] at it, except when he has been drinking too heavily.”

“Drinking! Mr. Frost, you surely are misinformed; Robert never drinks.”

Her manner was dignified, though she did not seem affected, for she was too certain there was some mistake.

“I hope I have been,” he said, simply.

He saw at once that she would not believe him. For love to her meant perfect trust; faith in the beloved against all earth or heaven. Whoever dared to traduce him would be consumed in the lightning of her luminous scorn, yet win for him, her lover, a tenderer devotion.

“So you are going to ‘Frisco,’ and I cannot see you for three long months? Well, I must explain something,” he began. “It is rather serious, it didn’t start out so, but is getting very serious. I got your note about the money more than a week ago—” His voice trembled, broke down, then mastering himself, he went on, “I could not meet the demand. Ah, if I could only get the model I wanted, I could paint a picture whose loveliness none but the blind could dispute—a picture that would bring more than three times the amount I owe you.”

He watched the girl eagerly, the while soft sensations and vague desires thrilled him.

Wasn’t it a wonder that something did not tell him, “It is monstrous, inhuman to thus prey upon the credulity of an impulsive, over sensitive nature.” Not when it is learned that whatever of heart, conscience, manliness, courage, reverence, charity, nature had endowed him at his birth, had been swallowed up in that one quality—selfishness.

“I wish I could help you,” Cherokee said timidly, “for I need the money. All I had has gone for my winter wardrobe.”

“Then I will tell you how to help us both. The model I want is yourself.” He spoke bravely now.

“Me?”

“Yes, if you will let me, I can do us both justice, and you will be counted the dream of all New York.”

She listened to his speech like the bird that flutters around the dazzling serpent; she was fascinated by this dangerous man, and neither able nor honestly willing to escape.

“Besides, I will make your portrait for Mrs. Stanhope free of charge,” was the artist’s afterthought.

“I could not accept so much from you,” she answered, promptly.

“I offered it by way of rewarding your own generosity, but come, say you will pose for me anyhow.”

She regarded him frankly and without embarrassment.

“I will if it is perfectly proper for me to do so. Surely, though, you would not ask me to do it if it were wrong.”

“Not for the world,” he replied magnanimously. “It is entirely proper, many a lady comes there alone. ‘In art there is no sex, you know.’”

“But I am not prepared now, how should I be dressed?”

“In a drapery, and I have all that is necessary. Say you will go,” he pleaded.

She hesitated a moment.

“Well, I will,” was the unfortunate answer.

Within an hour, master and model entered the studio.

“Now, first of all,” observed the master, “you must lay aside all reserve or foolish timidity, remembering the purity of art, and have but one thought—the completion of it. In that room to your right you will find everything that is needed, and over the couch is a study by which you may be guided in draping yourself.”

As the door closed behind Cherokee, Willard Frost caught a glimpse of a beautiful figure, “The Nymph of the Stream.” He listened for a couple of minutes or more, expecting or fearing she would[Pg 50] be shocked at first, but as there was no such evidence he had no further misgivings. A thousand beautiful visions floated voluptuously through the thirsting silence. They flushed him as in the wakening strength of wine. And his body, like the sapless bough of some long-wintered tree, suddenly felt all pulses thrilling.

His hot lips murmured, “Victory is mine. Aye, life is beautiful, and earth is fair.”

Then the door opened and the model entered. She did not speak but stood straight and silent, her hands hanging at her side with her palms loosely open—the very abandonment of pathetic helplessness.

The master drew nearer and put out his hands. “Cherokee,” he said.

But he was suddenly awed by a firm “Stop there! I have always tried to be pure-minded, high-souled, sinless, but all this did not shield me from insult,” she cried, with a look of self-pitying horror.

“But he was suddenly awed by a firm ‘Stop there!’” Page 50.

He drew back, and his temper mounted to white heat, but he managed to preserve his suave composure.

“My dear girl, you misunderstand me; art makes its own plea for pardon. You are not angry, are you?”

She looked straight at him, her bosom rose and fell with her quick breathing, and there was such an eloquent scorn in her face that he winced under it, as though struck by a scourge.

“You are not worth my anger; one must have something to be angry with, and you are nothing—neither man, nor beast, for men are brave and beasts tell no lies. Out of my way, coward!”

And she stood waiting for him to obey, her whole frame vibrating with indignation like a harp struck too roughly. The air of absolute authority with which she spoke, stung him even through his hypocrisy and arrogance. He bit his lips and attempted to speak again, but she was gone from the studio.

Every step of her way she saw a serpent crawl back and forth across her hurried path, and she mused to herself: “Let him keep the money, my virtue is worth more to me than all that glitters or is gold.”

Robert Milburn, bent at his desk, his fair head in his hands, was bewildered, angry, in despair.

“Can this be true?” he asked himself. “Is there a possibility of truth in it?”

The air of the gray room grew close, oppressive to the spirit, and at the darkening window he arose from the desk. He put on his long rain-coat, and with a hollow, ominous sound, the door closed behind him and he left the house.

As along he went, Robert caught sight of the bony face of an American millionaire and a beautiful woman in furs, behind the rain-streaked panes of a flashing carriage. On the other side he observed a gigantic iron building from which streams of shop-people poured down every street homeward; these ghastly weary human machines made a pale concourse through the sleet.

Further on his way a girl stood waiting for some one on the curb. He looked at her, dark hair curled on her white neck, her attire poor and common; but she was pretty, with her dark eyes. A[Pg 53] reckless, plebeian little piece of earth, shivering, her hands bare and rough, the sleet whipping her face, on the side of which was a discoloration—the result of a blow, perchance. Then he turned his eyes from her who had drawn them.

The arc light above him hung like a dreadful white-bellied insect hovering on two long black wings, and he saw a woman in sleet-soaked rags, bent almost double under a load of sticks collected for firewood. Her hair hung thin and gray in elf-locks, her red eyelids had lost their lashes so that the eyes appeared as those of a bird of prey. The wizened hands clutching the cord which bound the sticks seemed like talons. She importuned a passer-by for help, and, being denied, she cursed him; and Robert watched the wretched creature crawl away homeward—back to the slums.

These were manifestations of the life of thousands in metropolitan history. Robert shook himself, shuddering, as though aroused from a trance.

He had started out to go anywhere or nowhere, but the next hour found him in the presence of Cherokee, and she was saying:

“How awfully fond you are of giving pleasant surprises.”

“I am amazed at myself for coming such a night, and that too without your permission.”

“We are always glad to see you, but Fred and I had contemplated braving the weather to go to hear Paderewski,” she said, sweetly.

“Then don’t let me detain you, I beg of you,” he answered, with profound regret.

“Oh, that’s all right, we have an hour or more, I am all ready, so you stay and go in as we do.”

“No, I will not go with you, but will stay awhile, since you are kind enough to permit me.” And he laughed, a little mournfully.

“Cherokee, I have come for two reasons—to tell you that I am going home to Maryland to see a sick mother, and to tell you——” He paused, hesitating, a great bitterness welled up in his breast; a firmness came about his mouth and he went on:

“It is folly for you to persuade yourself that you could accommodate your future life to sacrifice, poverty—this is all wrong. When we look it coldly in the face it is a fact, and we may dispute facts but it is difficult to alter them.”

There was no response from her except the clasping of the hand he held over his fingers for a moment.

“I had no right that you should wait for me through years, for your young life is filled with possibilities. I, alone, make them impossible, and I must remove that factor.”

“Robert! Robert! What does all this mean?” Her breathless soul hung trembling on his answer.

“It means that I am going to give you back your liberty.”

“And you?” she gasped.

“I will do the best I can with my life. Please God, you shall never be ashamed to remember that you once fancied that you could have cared for me.”

And then he could trust himself no further; the trembling fingers, the soft perfume he knew so well in the air, and the surging realization that the end was at hand, made him weak with longing.

Cherokee was at first shocked and stunned at what he was saying? For a moment the womanly conclusion that he no longer cared for her seemed the only impression, but she put it from her as being unworthy of them both.

Her manner was dignified, yet tender, as she began:

“Robert, I suppose you have not spoken without consideration, and if you think I would be a burden to you, it is best to go on without me.” She ended with a deep-drawn breath.

“That sound was not a sob,” she said bravely, “I only lost my breath and caught it hard again.”

“Yes, Cherokee, I am going without you, going out of your life. Good bye.”

“You cannot go out of it,” she answered, “but good bye.”

“Good bye,” he repeated, which should only mean, “God bless you.”

There was a flutter of pulses, and Robert walked away with head upheld, dry-eyed, to face the world. Unfaltering, she let him go, the while she had more than a suspicion of the lips whose false speaking had wrought her such woe.

When he reached his room he unlocked the drawer, produced from it a card, and looked long and tenderly upon the face he saw. He bent over and kissed the unresponsive lips. This was his requiem in memory of a worthier life. Then lighting a match he set it afire, and watched it burn to a shadowy cinder, which mounted feebly in the air for a moment, making a gray background against whose dullness stood out, in its round finished beauty, the life he had lost—echoing with a true woman’s beautiful soul.

As the ashes whitened at his feet, he thought, “Thus the old life is effaced, I will go into the new.”

The midnight train took him out of town, and Cherokee was weeping over a basket of white roses which had come just at evening.

Now and again Cherokee kissed the roses with pangs of speechless pain. The fragrance that floated from their lips brought only anguish. To her, white roses must ever mean white memories of despair, and their pale ghosts would haunt long after they were dead.

All day the family had been busy packing, for soon the Stanhopes would close the house and take flight. Cherokee had been forced to tell them she had changed her mind and would go to the country; she needed quiet, rest. Pride made her withhold the humiliating fact that she had just money enough to take her down to the South country.

There was a kind, generous friend, who, at her father’s death, offered her a home under his roof for always, and now that promise came to her, holding out its inducement, but she would not accept it; somehow she felt glad that the time of leaving the Stanhopes was near. This pleasant house, these cheerful, affectionate surroundings, had become most intolerable since she must keep anything[Pg 58] from them—even though it be but an error of innocence.

“Let me forget the crushing humiliation of the past month,” she told herself, “I must try to be strong, reasonable, if not happy.” She must find some calling, something to sustain herself, to occupy her hands and time. The soft, idle, pleasant existence offered by the friend would enervate rather than fortify—would force her back on herself and on useless regrets.

As she sat in her own room, holding the blank page of her coming life, and studying what the truth should be, there arose before her inner gaze two scenes of a girlish life; fresh, vivid were they, as of yesterday, though both were now of a buried past.

First she recalled the hour when sorrow caught her by the hand, dragged her from the couch of childhood to a darkened room where lay the sphinx-like clay of her mother—the lids closed forever over what had been loving gleams of sympathy—the hands crossed in still rigidity. Her little child heart had no knowledge of the mysteries—love, anguish, death—in whose shadow the zest of life withers. She knew their names but they stood afar off, a veiled and waiting trio.

She crept, sobbing, from that terrible semblance of a mother to the out-door sunshine, and the yard,[Pg 59] where the crape-myrtle nodded cheerfully to her just as it did before they frightened her so. The dark house she was afraid of, so she had gone far out of doors. The little lips that had lately quivered piteously, sang a tune in unthinking gaiety, and life was again the same, for she could not then understand.

The other scene was a radiant, sparkling, wildly joyous picture. The world, enticing as a fairy garden, received her in her bright, petted youth—her richly endowed orphanhood had been a perpetual feast. In this period not one single voice of cold or ungracious tenor could she recall.

But now she looked full over that garden, once all abloom. Here a flower with blight in its heart, yonder one whose leaves were falling. There whole bushes were only stems enthorned, and stood brown and bitter, leaves and flowers withered or dead.

“So,” thought she, “it is with my life.” A rap on the door brought her into the present. It was the delivery of the latest mail: some papers, a magazine, and one letter. The letter was postmarked Winchester, Ky. With a little sigh of triumphant expectation, she broke the seal. It, to her thinking, might contain good news from friends at home.

It only took her a moment to scan it all.

“I am sick and needy. Won’t you help me for I am dying from neglect.” This was signed:

“Black Mammy,

“Judy, (her X mark.)”

Cherokee read it again. Her eyes closed, and then opened, dilating in swift terror. Her slave-mother suffering for the necessities of life. She who had spent years in chivalrous devotion to the Bell family now appealed to her, the last of that honored name.

A swift pain shot through her veins—a sudden increased anguish—a sense of something irremediable, hopeless, inaccessible, held her in its grip, and a voiceless, smothered cry rent her breast. Tears gushed from her eyes, scalding waters which fell upon her hands and seemed to wither them. Even the fern-leaf, the birth-mark, looked shrunken and shrivelled, as she gazed at it; something told her to remember it held the wraith of a life.

Cherokee was wild with grief. She went to the window and looked far out into the night, letting her sight range all the Southern sky, and the stars looked down with eyes that only stared and hurt her with their lack of sympathy. A gentle wind[Pg 61] crept by, and a faint sibilance, as of taut strings throbbed through the coming night. It was Fred, with his violin, waiting for her to come down to accompany him. But she did not go—she had no thought of it being time to eat or time to play—she had forgotten everything, except that a soul had cried to her and she must answer it in so niggardly and miserly a fashion.

Now three, four, five hours had gone since the sunken sun laved the western heaven with lowest tides of day. The tired world, that ever craves for great dark night to come brooding in with draught of healing and blessed rest that recreates, had been lulled to satisfaction. Still mute sorrow held Cherokee, and it was nearly day when peace filled her unremembering eyes and she had forgotten all.

It was a dull, wintry day; blank, ashen sky above—grassland, sere and stark, below. Weedy stubble wore shrouding of black; everything was still—so still, even the birds yet drowsed upon their perch, nor stirred a wing or throat to enliven the depressing wood. A soiled and sullen snowdrift lay dankly by a road that had fallen into disuse. It was crossed now for the first time, maybe, in a full year. A young woman tramped her way along the silent waste to a log shanty. Frozen drifts of the late snow lay packed as they had fallen on the door sill.

She rapped at the door and bent her head to listen; then she rattled it vigorously, and still no answer. She tried the latch, it yielded, and she entered. The light inside was so dim that it was hard at first to make out what was about her. Two hickory logs lay smouldering in a bank of ashes. She stirred the poor excuse for fire, and put on some smaller sticks that lay by the wide fireplace. By this time her eyes had become accustomed to the dimness, and she looked about her. There[Pg 63] were a few splint-bottomed chairs, a “safe,” a table, and a bed covered with patched bedding and old clothes, and under these—in a flash she was by the bed and had pushed away the covering at the top.

“She is dead,” Cherokee heard herself say aloud, in a voice that sounded not at all her own; but no, there was a feeble flicker of pulse at the shrunken wrist that she instinctively fumbled for under the bed clothes.

“Mammy wake up! I have come to see you—it’s Cherokee, wake up!” she called.

The faintest stir of life passed over the brown old face, and she opened her eyes. It did not seem as though she saw her or anything else. Her shrivelled lips moved, emitting some husky, unintelligible sounds. Cherokee leaned nearer, and strained her ears to catch these terrible words:

“Starvin’—don’t—tell—my—chile.”

With a cry she sprang to her feet; the things to be done in this awful situation mapped themselves with lightning swiftness before her brain; she started the fire to blazing, with chips and more wood that somehow was already there. Then she opened the lunch she had been thoughtful enough to bring; there was chicken, and crackers, and bread. She seized a skillet, warmed the food,[Pg 64] hurried back to the bed, and fed the woman as though she had been a baby.

Soon she thought she could see the influence of food and warmth; but it hurt her to see in the face no indication of consciousness; there was a blank stare that showed no hope of recognition.

As she laid the patient back upon the pillow of straw there was a sound at the door, a sound as of some one knocking the mud from clumsy shoes. A colored woman stepped in.

“How you do, Aunt Judy?”

“Don’t disturb her now, she is very weak,” warned Cherokee.

The visitor looked somewhat shocked to see a white lady sitting with Aunt Judy’s hand in hers, softly rubbing it. “What’s ailin’ her?” she questioned in a whisper, “we-all ain’t hearn nothin’ at all.”

“I came and found her almost dead with hunger, and she is being terribly neglected.”

“Well! fo’ de lawd, we-all ain’t hearn nary, single word! I ’lowed she was ’bout as common; course I know de ole ’oman bin ailin’ all de year, but I didn’t know she was down. I wish we had ha’ knowed it, we-all would a comed up and holped.”

“It is not too late yet,” said Cherokee, gently.

“Yes um, we all likes Aunt Judy, she’s a good ole ’oman, I thought Jim was here wid her. Don’t know who he is? Jim is her gran’son, a mighty shiftless, wuthless chap, but I thought arter she bin so good to him he’d a stayed wid her when she got down. But I’ll stay and do all I kin.”

Cherokee thanked her gravely, gratefully.

The darkey went on whispering:

“De ole ’oman bin mighty ’stressed ’bout dyin’. She didn’t mind so much the dyin’ ez she wanted to be kyaried to de ole plantation to be buried ’long wid her folks. Dat’s more’n ten or ’leven miles, and she knowd dey wouldn’t haul her dat fur—’spec’ly ef de weather wus bad. I ’spec worrin’ got her down.”

Cherokee told the visitor to try and arouse her, now that she had had time to rest after her meal.

She took up one of her worn brown hands.

“How do you feel, Aunt Judy?”

“Porely, porely,” she stammered almost inaudibly.

“Why didn’t you let we-all know?”

“Thar warn’t nobody to sen’ ’roun’.”

“Whars Jim?” the visitor enquired.

Her face gloomed sadly.

“Law, hunny, he took all de money Mas’r left me, and runned away.” She looked up with tears in her eyes.

“Tildy, I mout’ent o’ grieved ’bout de money, but now dey’ll bury me jes like a common nigger—out in de woods.”

“Maybe not, sumpin’ mite turn up dat’ll set things right,” she said, comfortingly.

The old woman talked with great effort, but she seemed interested in this one particular subject.

“Tildy, I ain’t afeard ter die, and I’se lived out my time, but we-all’s folks wus buried ’spectable—buried in de grabe-yard at home. One cornder wus cut off for we-all in deir buryin’ groun’; my ole man, he’s buried dar, and Jerry, my son, he’s buried dar, and our white people thought a sight o’ we-all. Dey’ed want me sent right dar.”

“Whar dey-all—your white folks?” asked Tildy, wistfully.

“All daid but one—my chile, Miss Cheraky. I wus her black mammy, and she lub’d me—if she was here I’d——” She broke down, crying pitifully—lifting her arms caressingly, as though a baby were in them.

Cherokee knew now that she would recognize her, so she came up close to her.

“Yes, Mammy, you are right, our loved ones should rest together, I will see that you go back home.”

“Oh, my chile!”—she caught her breath in a sob of joy, “God A’mighty bless you, God A’mighty bless you!”

“Don’t excite yourself, I shall stay until you are well, or better.” Cherokee stooped and patted her tenderly.

“My chile’s dun come to kyar ole mammy home,” she repeated again and again, until at last, exhausted from joy, she fell asleep.

Tildy and the young white lady kept a still watch, broken only by stalled cattle that mooed forth plaintive pleadings.

Cheerless winter days were gone. Spring had grown bountiful at last, though long; like a miser

But her penitence was wrought in raindrops ringed with fragile gold—the tears that April sheds. Now vernal grace was complete; the only thing to do was to go out in it, to rejoice in its depth of color, in its hours of flooded life, its passion pulse of growth.

“Ashland,” that peerless Southern home, was set well in a forest lawn. The great, old-fashioned, deep-red brick house, with its broad verandas, outlined by long rows of fluted columns, ending with wing rooms, was half ivy-covered. A man came out upon the steps and looked across his goodly acres. Day-beams had melted the sheet of silvery dew. A south wind was asweep through fields of wheat, a shadow-haunted cloth of bearded gold, and blades of blue grass were all wind-tangled too. How the[Pg 69] wind wallowed, and shook, with a petulant air, and a shiver as if in pain. The man looked away to the eastward, to where even rows of stalls lined his race-course—a kite-shaped track.

A darkey boy came up with a saddled mare, and the master took the reins, put foot in the stirrup and mounted to the saddle. He was a large, finely built man, fresh in the forties; kindness and determination filled the dark eyes, and the broad forehead was not unvisited by care. The hand that buckled the bridle was fat, smooth and white, very much given to hand-shaking and benedictions. As he was about to ride away, the jingling pole-chains of a vehicle arrested his attention. Looking around the curve, he saw a carriage coming up—a smartly dressed man stepped out, who asked:

“Have I the honor—is this Major McDowell?”

“That is my name, sir; and yours?”

“Frost—Willard Frost,” returned the other, cordially extending his hand.

The Major said, warmly:

“Glad to know you, Mr. Frost; will you come in?” and the Major got down from his horse.

“Thanks. I came with the view of buying a racer. Had you started away?”

“Only down to the stables; you will come right over with me,” he proposed.

“Very good. To go over a stock farm has been a pleasure I have held in reserve until a proper opportunity presented itself. Shall I ride or walk?”

“Dismiss the carriage and be my guest for the day, I will have you a horse brought to ride.”

“Oh, thank you, awfully,” returned the profuse stranger. And he indicated his acceptance by carrying out the host’s suggestion.

“Call for me in time for the east-bound evening train,” he said, to the driver.

Pretty soon the Major had the horse brought, and they rode down to the stables.

“I think, Mr. Frost, I have heard your name before.”

The other felt himself swelling. “I shouldn’t wonder; I am a dauber of portraits, from New York, and you I have heard quite a deal of, through young Milburn.”

“Robert Milburn! Why bless the boy, I am quite interested in his career; he, too, had aspirations in that line. How did he turn out?” asked the Major, with considerable interest.

“Well, he is an industrious worker, and may yet do some clever work, if drink doesn’t throw him.”

“Drink!” exclaimed the other, “I can scarcely believe it. He impressed me as a sober youth, full[Pg 71] of the stuff that goes to make a man. What a pity; I suppose it was evil associations.”

“A pretty girl is at the bottom of it, I understand. You know, ‘whom nature makes most fair she scarce makes true.’”

The Major re-adjusted his hat, and breathed deeply.

“Ah! well, I don’t believe in laying everything on women. Maybe it was something else. Has he had no other annoyance, vexations or sorrow?”

“Yes, he lost his mother in mid-winter, but I saw but little change in him; true, he alluded to it in a casual way,” remarked Frost, lightly.

“But such deep grief seeks little sympathy of companions; it lies with a sensitive nature, bound within the narrowest circles of the heart; they only who hold the key to its innermost recesses can speak consolation. From what I know of Robert Milburn this grief must have gone hard with him.”

Here they came upon the track where the trainer was examining a new sulky.

“Bring out ‘Bridal Bells,’ Mr. Noble. I want to show the gentleman some of our standard-breds.”

The trainer’s lean face lighted with native pride. With little shrill neighs “Bridal Bells” came prancing afield; she seemed impatient to dash headlong[Pg 72] through the morning’s electric chill. Pride was not prouder than the arch of her chest.

“What a beauty, what a poem!” Frost’s enthusiasm seemed an inspiration to the Major.

“She is marvellously well favored, sir; comes from the ‘Beautiful Bells’ family, that is, without a doubt, one of the richest and most remarkable known. If you want a good racer she is your chance. Racing blood speaks in the sharp, thin crest, the quick, intelligent ear, the fine flatbone and clean line of limb.”

Frost looked in her mouth, put on a grave face, as though he understood “horseology.”

The Major gave her age, record, pedigree and price so fast that the other found it difficult to keep looking wise and listen at the same time.

The trainer then brought out another, a brown horse with tan muzzle and flanks.

“Here, sir, is ‘Baron Wilkes’; thus far he has proven an extremely worthy son of a great sire, the peerless ‘George Wilkes.’ He was bred in unsurpassed lines, is 15½ hands high, and at two years old took a record of 2:34¼.”

“Ah! he is a handsome individual; look what admirable legs and feet,” exclaimed the guest.

“And a race horse all over. But here comes my ideal,” he added, with pride, as across the sward[Pg 73] pranced a solid bay without any white; black markings extending above his knees and hocks. A horse of finish and symmetrical build, well-balanced and adjusted in every member. The one prevailing make-up was power—power in every line and muscle. Forehead exceedingly broad and full, and a windpipe flaring, trumpet like, at the throttle.

“Now I will show you a record-breaker,” the while he patted him affectionately.

“This is ‘Kremlin,’ unquestionably the fastest trotter, except illustrious ‘Alix.’ Under ordinary exercise his disposition is very gentle, there being an independent air of quiet nonchalance that is peculiarly his own. Harnessing or unharnessing of colts, or the proximity of mares, doesn’t disturb his serene composure. But roused into action his mental energies seem to glow at white heat. He is all life, a veritable equine incarnation of force, energy, determination—a horse that ‘would meet a troop of hell, at the sound of the gong,’ and, I might add, beat them out at the wire. His gait, as may be judged from his speed, is the poetry of motion; no waste action, but elastic, quick, true. He is a natural trotting machine. His body is propelled straight as an air line, and his legs move with the precision of perfect mechanism.”

“What shoe does he carry?” asked the New Yorker.

“Ten ounces in front, five behind.”

“He is certainly a good animal, I should like to own him; but, all around, I believe I prefer ‘Bridal Bells.’ To own one good racer is a pleasure. I take moderate, not excessive, interest in races,” explained Frost.

“It is rather an expensive luxury, if you only view it from the standpoint of pleasure and pride.”

“Oh, when we can afford these things, it is all very well, I have always been extravagant, self-indulgent,” and he took out his pocket book.

“I must have her,” counting out a big roll of bills and laying them in the Major’s hand. “There is your price for my queen.” And “Bridal Bells” had a new master.

Like most Southerners, Major McDowell had the happy faculty of entertaining his guests royally.

The New Yorker was there for the day, at the kind solicitation of the Major and his most estimable wife. Afternoon brought a rimming haze; the wind had hushed, and the thick, lifeless air bespoke rain. A cloud no bigger than a man’s hand had gathered at low-sky; then mounted, swelling, to the zenith, and wrapped the heavens in a pall and covered the earth’s face with darkness that was fearfully illumined by the lightning’s glare.