Man has evolved slowly, always

striving toward a nebulous goal

somewhere in his future. Will

he attain it—to regret it?...

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

December 1950

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Striding down the corridor on long thin legs, Art Fillmore mentally glanced over the news and his wide brow puckered. "Scientists to awaken twentieth century man," the mental beam proclaimed. "Dark age to yield untold volumes of ignorance."

Fillmore paused before the twelve-foot door, closed his eyes and concentrated until he had achieved the proper attenuation, then entered the office without opening the door. The bald man in the reclining chair dropped his feet from the five-foot-high desk and sat up with a start.

"I wish you wouldn't do that, Art," he said nervously. "You know I've got the itch."

"Sorry," Fillmore apologized. "Wasn't thinking. Had my mind on my forthcoming wedding."

"Wedding?" The bald man's narrow mouth dropped open, revealing small fragile teeth. "Why didn't you tell me? What does she look like?"

"Haven't seen her yet," Fillmore grinned. "Just mental images, and you know how girls are when they project their own images. But she's a mental pippin: seven feet eight or nine with a shape you dream about. Must weigh about eighty-two or three pounds."

"Too fat," the bald man grunted. "I never liked the short and fat type. Have you paid for her yet?"

"Not yet, but I've got the cash and I'll get a discount."

"How much?"

"Dollar sixty-nine less three per cent."

"Good Lord!" The bald man leaned forward, aghast. "For that price she must be a pippin. Why, you can buy two hundred average women for that and the market's glutted with them. How old is she?"

"Hundred and nine."

"Oh! That explains it. You're practically getting her right out of the cradle and can teach her whatever you want her to know and see that she doesn't learn anything else. Has she got any mental quirks?"

Fillmore sighed. "She's almost perfect in that respect. Doesn't have to have her mind erased but once every six weeks. Nine power intelligence but she holds it back. That way she doesn't come anywhere near a nervous breakdown oftener than once in six weeks."

"Domestic type?"

"Definitely. Regular homebody. Never been out of the solar system. She's the kind that likes a quiet picnic on Mars and will settle for the moon when Mars is crowded. Besides, she's interested largely in warts and mice. Studies them all the time. Knows how to grow warts on anybody."

"You're a lucky man, Art. Planned the honeymoon yet?"

"Sure. She's going to Venus while I go in the opposite direction. Haven't decided yet where I'll spend that happy time. On one of the planets of the nearer stars, I suppose."

"That's perfect," the bald man said approvingly. "My wife made me stay on earth while she went to the moon. That's too close for comfort. After all, you don't have but one real honeymoon, and in my opinion every man and woman should strive to make it as nearly perfect as possible. I think the government ought to subsidize that sort of thing. Then the happy couple could put more distance between them. Think what bliss could be achieved if the man could afford to go the maximum distance in one direction and send his wife twice that far in the other direction. I mean to say, happiness is next to the ultimate, and if they could be separated so far that no trace of one ever got back to the other—well, just think of it! We would never hear of divorce again."

Fillmore's thin angular features darkened. "It is sad to think of the divorces. There's been a dozen in the past half a century. But isn't it because the couples were immature? Some of them married at under eighty years of age, and they insisted on living on the same side of the earth with each other."

"You're pretty young yourself," the bald man put in.

"I'm ninety-six," Fillmore said defensively. "That's plenty old for a man. All of my people matured early."

"And probably died early."

"Yes." Fillmore nodded. "A few of them lived to be nearly five hundred, but they were mostly females. The males usually check out between two and three hundred. Their fourteen power intelligence burns them up."

"Had your mind erased recently?"

"Yesterday. Did it so I could accept Cynthia's proposal without any reservation."

"Cynthia?"

"That's what I call her. Her real name is Xylosh. She found the name Cynthia in one of those books of ignorance unearthed from the ruins of that ancient farm called New York. She asked me to call her by that name. You know how girls are!"

"Sure. They are all very romantic. She may even expect you to be present at the wedding."

Fillmore shook his head and grinned. "She knows better than to spoil things. And I love her too much to let anything like that happen. The ceremony will take place near the earth at the hour when the north pole and the south pole swap places. I'll be somewhere beyond the sun at that time."

"Figuring on any children?"

"Of course. She wants three. We'll have them just before the ceremony."

"That's fine. Gets the dirty work out of the way before marriage and then there's nothing to spoil it. But how are you figuring—"

"That's what I came to see you about. I want to borrow your secretary."

"For what?"

"Well, it's like this. I'm old fashioned. I believe there ought to be some personal contact between a man and his wife before they have children. These laboratory things are so cold-blooded. Mental projections are much better. But there ought to be some personal contact."

"So?"

"So I want to shake hands with your secretary, then she'll shake hands with you and you shake hands with one of your men who's going east and he shakes hands with somebody on the east coast who knows Cynthia's father and that man shakes hands with her father and her father shakes hands with one of his men who shakes hands with his secretary who passes it along until it finally comes to Cynthia. That will give the matter a sort of warmth and personal touch, and then, just before the ceremony, Cynthia and I will mentally project the three children."

"Very touching," the bald man said almost tearfully. "I doubted at first that you and Cynthia actually loved each other, but I see now that any two people so affectionate can't help but love one another. You'll love the children, too."

"Of course. We're going to materialize them fully developed in the government nursery. It will take two or three minutes longer, but we intend to give them a well-rounded education at the beginning. I want the boys to understand the simpler mathematics, such as the theory of relativity and why it is possible to add numerals until you get an answer of zero square. Of course, not everyone can square zero, and it may take ten or fifteen seconds just to teach them that, but I don't want them to grow up to be two or three hours old and still be ignorant. Then, after they've learned those little unimportant things, I'll get down to the business of teaching them everything there is to know. It will take over two minutes and possibly three. Then we'll erase their minds."

"Very ambitious. But what about the girl?"

"Cynthia thinks she ought to learn about warts and I agree. If she learns to grow warts she'll have a first-class female education. I can't think of anything finer in our society. And Cynthia even plans to teach her all about mice."

"It's beautiful," the bald man said. "I'll have my secretary in whenever you're ready."

"Thanks. But not just yet. Chloroform her first. It makes me nervous to be around conscious females. They talk too much."

"Naturally. I don't expect to allow her to speak in your presence. Think I'm a fool without morals? We've got to preserve the conventions. If she saw those three strands of hair on your head she'd swoon. You're the only man in the nation with more than twelve power intelligence who isn't bald. If I didn't know you well I'd think you were effeminate. My wife got a mental glimpse of you once and said you were the handsomest man extant. It's those three strands of blond hair. Even the most beautiful woman in the world doesn't have more than six or seven. I'll bet you really projected those in a big way for Cynthia."

Fillmore felt the blood rising to his pale cheeks. "I didn't make any special effort," he denied. "Anyway, I'm very presentable. Just under nine feet tall and weigh close to a hundred. My forehead is twelve inches across and eight inches high from the root of the nose. That's better than average. Few men measure more than eleven inches across the forehead."

"True," the bald man admitted "And some persons are troubled with a chin. Fortunately you don't have one. I've got to admit that you are typical of the finer specimens of masculine beauty. Do you ever have a headache?"

"Not since I had my skull cracked. Finest Ducktor in the realm did it with a hammer. Said I needed more room to let my brain expand."

"Of course. I've got a two-inch brain expansion myself. Had to soak my skull in oil until it became malleable enough to allow for the normal brain growth. I've heard of some men having their brain taken out."

"Yeah. Some people are better off without it. But then they have to install an antennae. I wouldn't like that. Which reminds me of something: Got a news flash that scientists were going to awaken a twentieth century man. I don't approve of that sort of thing, but I'm going along to watch. Last time they awakened something from the past it took us quite a while to recover from the mental shock. Had to have my mind erased six times in as many days. Couldn't we do something to stop it?"

"There might be something," said the bald man. "Corson was working on something that would eliminate the past and make everything the present. Only trouble seemed to be that the future got mixed up in it. No. We don't have much chance in that direction—unless—"

"I know what you're thinking," Fillmore said. "I've been working on it myself. Gave it nine seconds solid thought yesterday. If I hadn't been interrupted I might have got it. You're thinking about pure reasoning before the fact."

"Exactly. What are your conclusions?"

"It's possible. The square of nothing equals nothing. When you put nothing times nothing on paper it comes out minus infinity or infinity minus. Thus you have something. Take a mind without a fact and let it confront nothing. Almost at once it will raise nothing to the power of six. It will still have nothing, and so it will head in the other direction until it gets down to infinity minus. That in itself is reasoning a priori. Now it has a foundation and from that it can arrive at any conclusion extant, and quite a few that don't exist. Is that what you had in mind?"

"No. I want a conclusion without troubling to confront the mind with even nothing. That is the only way to get pure reasoning."

"If you can give me ten seconds more I'll work it out for you."

"You've already been here thirteen seconds and I'm getting bored. I only get three thousand dollars a day for sitting here, and at slave wages like that I can't put up with too much."

Fillmore nodded. "And prices are away out of reach too. Only the other day I spent six cents for twelve barrels of thousand-year-old whiskey. The world has been aiming at high wages and low prices for the past ten thousand years and we're still slaving and starving. You never told me exactly what you do."

"I work pretty hard. You see, this chair has coils in it that convert heat into Zeta Rays by shortening the wave-length. I sit here for twenty-nine minutes each day, two days a month, and concentrate all my heat through the seat of my pants. It goes through the converter and comes out Zeta Rays in China. Zeta Rays are no good for anything except to convert ordinary rock into gold, so the Chinese pipe it to Russia. Gold, being soft, is good for nothing except to burn ceremoniously in accordance with the ancient religious rites, and so a lot of it is stolen and sold on the gray market to be converted into uranium. Uranium, being useless except for fissionable purposes, is used for fertilizer in the mineral laboratories where iron is grown. Iron is no good for anything except food, and you can't put very much of it in ordinary food, and so it is dissolved into an iron vapor and freed in the atmosphere. Iron vapor gets heavier as it cools, and so it settles on top of the clouds and holds them close to the earth and keeps the warmth of the world from escaping. So, as I sit here and warm this chair, I'm keeping the world warm."

"And getting only three thousand dollars for twenty-nine minutes of that sort of slave labor! Scandalous! I'll bet you can't afford more than a hundred vacations a year. We might as well be back in the dark age of the twentieth century. I've been advocating a one-minute work-day for the past decade, one day a month, two months a year. What good is civilization if it doesn't provide something for the poor working man? And people call me a visionary, with Utopian ideas! Bah! If I'm not mistaken, you're the man with the seat of his intelligence in the back of his lap! Right? You're being exploited!"

The bald man shook his head. "No. It's Corson who's got his intelligence in his back side. Mine is in the soles of my feet, according to Meyer who knows about such things. But Konwell claims the intelligence flows through the bloodstream in all persons."

"Not all," Fillmore contradicted. "But Konwell is right. The brain is merely the antennae. The more blood it gets the more it can express. For instance, in order to concentrate to the full power of fourteen I have to stand on my head. But I can't hang around here all day. Get your secretary in and let me shake hands with her."

"All right. But as a precaution you'd better close your eyes and bring your thoughts down to a six power level. She isn't too bright. It takes her nearly half a second to calculate the distance in inches from here to Andromeda and return via Pegasus—that is, unless you give her a clue to the problem. She's a plain dumbbell but fantastically beautiful. Tall as you are and weighs less than sixty pounds. What a shape! She turned down a billion-dollar contract to dance three minutes in a spot on one of the planets in the Milky Way. Plain dumb! But looks! And the clothes she wears! Dazzling! Imported from Eureka. Must have cost her two-bits or more for one dress with upward of sixty yards of material in it. Made my wife gape. Nearly bankrupted me, my wife did, buying clothes after that. Spent four dollars on her in less than six years. Ten thousand separate items. But, of course, she never found anything like that imported by my secretary. I doubt if there's another in the solar system, and I know there isn't another woman able to afford twenty-five cents for a single dress. I wonder where she gets her money! Her salary here is only seven hundred dollars a day, two days a month. I'll bet she hasn't got a million dollars to her name saved up. Spends every last cent she earns, probably. Ninety cents a quarter she pays for that seventeen room apartment of hers. My wife and I have only eighteen rooms between us, her twelve rooms in China and my six rooms here. Not large either. My six rooms cover only two acres of ground and extend a mere hundred feet in the air. Cramped! I can't afford anything better, not and save anything. I've got less than a billion put aside right now, hardly enough to invest in an enterprise outside the solar system. Poverty! How that secretary of mine lives so high on her pittance, I don't know. I wouldn't be surprised if she isn't consorting mentally with somebody on some planet on the edge of space. Not that I'm narrow-minded. A woman with looks like hers deserves the best, but allowing a man on the edge of space to think about her is going pretty far, and I'm a stickler for the convention.

"Hells bells. I didn't mean to run on like this. But it upsets me to think about her loose morals when I have to work the seat of my pants to the bone over a hot chair in order to earn a bare living. And my wife throwing money around for clothes, and both my boys getting ready to enter college and not in a position to earn anything."

"I can see you're upset. Better have your mind erased."

"I would, but there isn't a good Ducktor closer than Venus. Could find a doctor, of course, but they're unreliable. They style themselves doctors because it sounds like Ducktor. Plain disgrace. Ducktor comes from the word Quack. Ages old. Even in the dark ages there were plenty of quacks. They had all sorts of diseases then. Yes, sir. Diseases! Little crawley things working around in their blood and flesh. And these quacks would feed these diseases all sorts of medicine! Finally the diseases up and died. Not having any intelligence to burn them out, the people of those days could live as long as they wished. Or at least that's the way it's figured. Once in a while, about every two or three weeks, just as we erase our minds so we won't burn up too quick, those people would get together and begin killing one another. Think of it! We try to live, but they tried to die. Seems they couldn't die fast enough, so they used a lot of fissionable material and burned up everybody that way. Even that didn't satisfy them, so they used fusing material, which was more deadly, and finally completed everything to their total satisfaction. At least they left very little trace of themselves. Man had to begin all over again from the sea, beginning with the amoeba. I wonder if we're going to wind up like that a million years hence."

"Not likely," Fillmore said. "Besides, you're wrong. Man didn't begin all over again. The amoeba would have worked in another direction, seeing what a mess man made of things. What actually happened was that quite a few people were left after the hydrogen chain was set off. They lived on one of the nearer planets and returned after earth had cooled again. Then they set up things, or so they claimed, very much like they were before, with the exception that they changed their philosophy. Developed their minds first and everything else naturally followed."

"I think it's a mistake," the bald man persisted, "to develop the mind too early. As I mentioned, my two boys are just now entering college. Of course they knew a few things before, such as how to fuel themselves when in the presence of food, and how to walk, and the older one could even speak a few words, and even the younger one could change his own diaper—had been doing it since he was forty-nine—but my wife and I saw to it that they didn't learn too much too fast. That's the reason my people live so long. Don't burn ourselves up in infancy thinking. But that doesn't mean you may not be right in teaching your children, when you have them tomorrow, everything right at the start. With a fourteen power intelligence, your people are by nature compelled to do a lot of thinking, and it's your duty, as a citizen, to begin early. Had any startling thoughts lately?"

Fillmore sighed. "Just the normal ones. Figured out a simple method, just before dozing off to sleep last night, to transfer this planet to an orbit about another sun. Not that it will be of much use. A sun is a sun and it would take thirty seconds solid thought to improve on it, and I don't know anybody capable of that much sustained thought, and there's not much point in transferring this planet, now that we know how to renew the sun whenever it cools too much."

"But it's interesting," the bald man pointed out. "It gets sort of dull staying in the same old orbit. I'm in favor of moving to another universe. Why don't you bring the matter before the Council?"

"They wouldn't listen. They don't like change. Most of them are aged, and they still think in terms of light and energy. Imagine that in a modern world! Men content to travel at the mere speed of light! Can't get over the idea that breaking through the energy barrier was just like breaking through the sound barrier."

"Was it?"

"Not exactly. But the theory that at the speed of light matter will change to pure energy was just as ridiculous as the theory that matter would disintegrate into sound waves at the speed of sound. They figure light travels at 186,000 miles per second. Perhaps it does in a straight line. I never thought it was worth the trouble of figuring out. But light waves are always at right angle, different from sound waves, and we must come to the conclusion that light does not travel in a straight line, but in a series of curves. While its theoretical speed is 186,000 miles per second, its actual speed is many times that. Thus we have a constant and a variable. If there were only a constant, it would prove out that matter would become pure energy at the speed of the constant. But it does not, for it must achieve the speed of the variable, and that cannot be achieved without traveling at a million different speeds. And even if matter changed to pure energy it must necessarily change again when it breaks through the energy barrier. But those old slow pokes in the council insist that we go on traveling at less than the speed of light. They do not know that a billion miles per second is considered slow in some laboratories. They may know it but they ignore it. Backward! Stupid! Even the ancients were better informed. They conceived varying dimensions, which is a step in the right direction. Actually we know that there is only one dimension and that is the mental dimension with diverse corridors. But in order to learn that, we had to discover, some fifty thousand years ago, upward of two thousand different dimensions. Then we integrated them and found that they all emanated from the mind. It was merely a matter of mathematics and comprehension. And now everything is accomplished by the mind, and in another hundred thousand years we can dispense with our bodies."

"Is that good or bad?"

"Definitely good! We have the itch every few weeks and have to have our minds erased. Nerves! Without bodies we'd be without nerves. That, my friend, is the ultimate quest."

The bald man shook his head. "No. The ultimate quest is the elimination of both the body and the mind. Then we wouldn't have any troublesome thoughts."

"What would be left?"

"Us."

"How do you figure that?"

"I don't know. But you've got a fourteen power intelligence. Get the answer to it and you'll be famous."

"I'll do that. I'll do it right now."

"Not in here. Don't do any concentrating in here. I know how you are when you start thinking. Lightning crackling all around and furniture getting scorched and the building vibrating, and possibly even an earthquake. No, sir. You take your thinking home with you and get inside a thought-proofed vault. You know it's against the law to think above the seven power level out in public where you might start a hurricane or cause snow in the middle of summer."

"Yes. I can see you're right. We've got to get rid of our minds. They are troublesome. I'll go home and figure the whole thing out. And if it's safe I'll pass it along to the council. Good-bye."

"Wait! You want to shake hands with my secretary. I'm going to have her come in."

"That's right. I'd almost forgotten about Cynthia."

"That's another good thing about the elimination of the mind. We won't have to remember anything."

"Well, get her in."

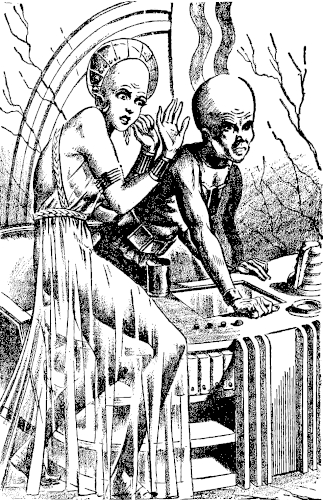

"Right now." The bald man turned his head slightly, glanced at a row of tubes in a panel, selected one and looked at it for a fraction of a second. Instantly the tube glowed brightly and the door of an adjoining office vanished and a woman appeared. Seven strands of jetblack hair on her massive chinless head gave her an ultra feminine appearance, and her eyes, behind their rimless radar equipment were almost as large as a pencil eraser, lending an innocent baby-like air to her lovely features.

She advanced in mincing four-foot strides, parted her tissue-thick lips, and spoke out of a ripe mouth that was fully half an inch wide. The tone of her voice was two octaves above high C, and it so stirred Fillmore with its rich depth that he was compelled to glance at her without opening his eyes. The mental effort was immediately felt by the others, as the temperature of the room increased, and the woman blushed prettily, swaying her lovely nine feet and sixty pounds of pulchritude. She looked at Fillmore, taking in the three strands of blonde hair on his waterbucket head, and swooned. She recovered before she struck the floor, however, and looked to see whether anyone had projected a mental couch for her to fall on. No one had, so she righted herself, readjusted her dress over her twelve-inch bust, patted her seven strands of hair into place, sat down, drew one sixteen-inch foot under her and waited expectantly.

Fillmore was almost on the point of opening his eyes. But he determined to stick to the conventions, because if he gave her any encouragement she might, he knew, try to get chummy with his mind, and that would lead to complications.

"Mr. Fillmore wants to shake hands with you," the bald man explained. "Then you pass it along to me."

"But why doesn't he shake hands with you?" she asked in high C.

The bald man shook his head. "You wouldn't understand about that. But it has something to do with the voltage. Men's voltage multiply, whereas a man and a woman's voltage merely add. If we shook hands we'd burn our brains out. But if you and he shake hands it will merely stimulate you two physically. Nothing dangerous about it."

"It seems immoral," she said.

"I hadn't thought of it that way," the bald man admitted. "But history reveals that men and women even went further than that centuries ago, and never thought anything about it."

The woman coyly lowered her eyes. "If he shakes hands with me," she said softly, "he really should marry me."

"Why?"

"Because I'd probably have a dozen children before tomorrow night."

"Good Lord!" the bald man exclaimed. "That's right. Have you thought about that, Fillmore?"

"No," Fillmore said. "My mind has been turned off for some time. But the hypothesis is reasonable. I'll have to figure out something."

"Not here."

"I've got to. Hold on to your chairs for a moment. I'm going to turn my mind on. Get ready for the shock."

"Not the fourteen power. Don't go over eight or nine."

"Think I'm a fool? I'll keep it down to seven power. Brace yourself, young lady. This is going to be a shock."

There was a moment of still silence, then the heat in the room began gradually to rise. In another moment the three blonde hairs were sticking straight up on Fillmore's head and waves of thought were washing about the room in an endless rising tide. The walls creaked and strained and the ceiling sighed upward elastically, giving as it was intended, and a thin gray haze obscured the natural light which was reflected from outside by means of a force field. Fillmore put a cigarette into his mouth, concentrated on the tip of it until it flared into flame, then resumed thinking for a total of two seconds.

"I have it," he said at last. "I'll pull out a strand of my hair, seal it in a ten-ton safe and ship it to Cynthia by armored tube. That is the greatest expression of love any man can possibly make."

"But," the woman broke in, "that is too much. I'm sure she would be satisfied with less."

"No." Fillmore shook his head. "The people of my clan are noted for their courage and chivalry. Should I choose to make the supreme sacrifice for my beloved, who is there to stop me? Call in the reporters. We'll make the announcement right now. My Cynthia shall be honored above women."

"It's beautiful," the woman sighed. "To be loved like that is something every woman dreams of."

"It may cause trouble," the bald man put in. "There was a case once in which a man came within speaking distance of his wife, and the women went wild about it. Some women even insisted on living near their husbands after that, and then the divorces began. You shouldn't do it, Fillmore. Take my word for it, you'll start something that will be hard to stop."

"Maybe you're right," Fillmore admitted. "Men have killed themselves for their wives, but that's nothing. They have given them planets, but that is nothing; they have showered them with stars, and that is very little because there are so many stars. But no man has ever given a woman, up until this time, a strand of his hair, largely because no man had any hair to give. Yes, it would cause trouble. You'd have to grow hair then, and that would cause the race to slip right back into the dark age. This is a problem that calls for fourteen power thought."

"Not here," the bald man shouted.

"Right here," Fillmore insisted. "I'll project a thought-proofed wall about me so that you won't get hurt."

"Well, don't take all day. You've been in this room nearly thirty seconds and haven't accomplished anything yet. Get to work and finish the task. But remember, don't shake this place down or burn it up."

"Relax," Fillmore said.

The bald man and the woman watched the wall grow and then become a sphere. They could easily tell that it was more than six feet thick and harder than a diamond, for it would take every bit of that to restrain Fillmore's full voltage. Besides, he sometimes became radio-active when he turned on full power.

The full matter required one point three seconds. Then the thought-proofed sphere was complete. Then began the dreary wait. Every second seemed like a light year. Five seconds passed, then ten, and still they waited. Then the woman sat bolt upright and uttered an exclamation.

"The sphere is bulging out," she screamed. "It's going to explode."

It was then that the bald man caught the thought beam that came through the sphere: "I've got it! Thinking about hair reminded me of the twentieth century man—he destroyed himself and the world with fissionable hydrogen—only he didn't really destroy himself! Do you get it? He only changed things.

"That's the answer. To eliminate the mind and body we don't destroy, we merely change. Change is the only definite thing anyway. Besides, it will be an interesting thing to cogitate on—the change."

The thought ended on an excited note. Then the sphere shimmered through the spectrum and with a pyrotechnic display burst outward.

Red, white, blue, purple, and finally black heat shot ten thousand miles through the earth below. The planet shuddered in protest, then disrupted into a gaseous nova. The ultimate quest had succeeded.

Just as in the dark age....

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.