The Project Gutenberg eBook of History For Ready Reference, Volume 1 (of 6), by Josephus Nelson Larned

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: History For Ready Reference, Volume 1 (of 6)

Author: Josephus Nelson Larned

Release Date: May 10, 2021 [eBook #65306]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

Produced by: Don Kostuch

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY FOR READY REFERENCE, VOLUME 1 (OF 6) ***

[Transcriber's Notes: These modifications are intended to provide

continuity of the text for ease of searching and reading.

1. To avoid breaks in the narrative, page numbers (shown in curly

brackets "{123}") are usually placed between paragraphs. In this

case the page number is preceded and followed by an empty line.

2. If a paragraph is exceptionally long, the page number is

placed at the nearest sentence break on its own line, but

without surrounding empty lines.

3. Blocks of unrelated text are moved to a nearby break

between subjects.

5. Use of em dashes and other means of space saving are replaced

with spaces and newlines.

6. Subjects are arranged thusly:

Main titles are at the left margin, in all upper case

(as in the original) and are preceded by an empty line.

Subtitles (if any) are indented three spaces and

immediately follow the main title.

Text of the article (if any) follows the list of subtitles (if

any) and is preceded with an empty line and indented three

spaces.

References to other articles in this work are in all upper case

(as in the original) and indented six spaces. They usually

begin with "See", "Also" or "Also in".

Citations of works outside this book are indented six spaces

and in italics, as in the original. The bibliography in

APPENDIX F on page xxi provides additional details, including

URLs of available internet versions.

----------Subject: End----------

indicates the end of a long group of subheadings or other

large block.

End Transcriber's Notes.]

-----------------------------------------------------------

History For Ready Reference, Volume 1 of 6

From The Best

Historians, Biographers, And Specialists

Their Own Words In A Complete

System Of History

For All Uses, Extending To All Countries And Subjects,

And Representing For Both Readers And Students The Better

And Newer Literature Of History In The English Language

By J. N. Larned

With Numerous Historical Maps From Original Studies

And Drawings By Alan C. Reiley

In Five Volumes

Volume I--A To Elba

Springfield, Massachusetts.

The C. A. Nichols Company., Publishers

MDCCCXCV

Copyright,1893,

By J. N. Larned.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

United States Of America

Printed by H. O. Houghton & Company.

Preface.

This work has two aims: to represent and exhibit the better

Literature of History in the English language, and to give it

an organized body--a system--adapted to the greatest

convenience in any use, whether for reference, or for reading,

for teacher, student, or casual inquirer.

The entire contents of the work, with slight exceptions readily

distinguished, have been carefully culled from some thousands of

books,--embracing the whole range (in the English language) of

standard historical writing, both general and special: the

biography, the institutional and constitutional studies, the

social investigations, the archeological researches, the

ecclesiastical and religious discussions, and all other important

tributaries to the great and swelling main stream of historical

knowledge. It has been culled as one might pick choice fruits,

careful to choose the perfect and the ripe, where such are found,

and careful to keep their flavor unimpaired.

The flavor of the Literature of History, in its best examples,

and the ripe quality of its latest and best thought, are

faithfully preserved in what aims to be the garner of a fair

selection from its fruits.

History as written by those, on one hand, who have depicted its

scenes most vividly, and by those, on the other hand, who have

searched its facts, weighed its evidences, and pondered its

meanings most critically and deeply, is given in their own words.

If commoner narratives are sometimes quoted, their use enters but

slightly into the construction of the work. The whole matter is

presented under an arrangement which imparts distinctness to its

topics, while showing them in their sequence and in all their

large relations, both national and international.

For every subject, a history more complete, I think, in the

broad meaning of "History," is supplied by this mode than could

possibly be produced on the plan of dry synopsis which is common

to encyclopedic works. It holds the charm and interest of many

styles of excellence in writing, and it is read in a clear light

which shines directly from the pens that have made History

luminous by their interpretations.

Behind the Literature of History, which can be called so in the

finer sense, lies a great body of the Documents of History, which

are unattractive to the casual reader, but which even he must

sometimes have an urgent wish to consult. Full and carefully

chosen texts of a large number of the most famous and important

of such documents--charters, edicts, proclamations, petitions,

covenants, legislative acts and ordinances, and the constitutions

of many countries--have been accordingly introduced and are easily

to be found.

The arrangement of matter in the work is primarily alphabetical,

and secondarily chronological. The whole is thoroughly indexed,

and the index is incorporated with the body of the text, in the

same alphabetical and chronological order.

Events which touch several countries or places are treated fully

but once, in the connection which shows their antecedents and

consequences best, and the reader is guided to that ampler

discussion by references from each caption under which it may be

sought. Economies of this character bring into the compass of

five volumes a body of History that would need twice the number,

at least, for equal fulness on the monographic plan of

encyclopedic works.

Of my own, the only original writing introduced is in a general

sketch of the history of Europe, and in what I have called the

"Logical Outlines" of a number of national histories, which are

printed in colors to distinguish the influences that have been

dominant in them. But the extensive borrowing which the work

represents has not been done in an unlicensed way. I have felt

warranted, by common custom, in using moderate extracts without

permit. But for everything beyond these, in my selections from

books now in print and on sale, whether under copyright or

deprived of copyright, I have sought the consent of those,

authors or publishers, or both, to whom the right of consent or

denial appears to belong. In nearly all cases I have received

the most generous and friendly responses to my request, and

count among my valued possessions the great volume of kindly

letters of permission which have come to me from authors and

publishers in Great Britain and America. A more specific

acknowledgment of these favors will be appended to this preface.

The authors of books have other rights beyond their rights of

property, to which respect has been paid. No liberties have been

taken with the text of their writings, except to abridge by

omissions, which are indicated by the customary signs. Occasional

interpolations are marked by enclosure in brackets. Abridgment by

paraphrasing has only been resorted to when unavoidable, and is

shown by the interruption of quotation marks. In the matter of

different spellings, it has been more difficult to preserve for

each writer his own. As a rule this is done, in names, and in the

divergences between English and American orthography; but, since

much of the matter quoted has been taken from American editions

of English books, and since both copyists and printers have

worked under the habit of American spellings, the rule may not

have governed with strict consistency throughout.

J. N. L.

The Buffalo Library,

Buffalo, New York, December, 1893.

Acknowledgments.

In my preface I have acknowledged in general terms the courtesy

and liberality of authors and publishers, by whose permission I

have used much of the matter quoted in this work. I think it now

proper to make the acknowledgment more specific by naming those

persons and publishing houses to whom I am in debt for such kind

permissions. They are as follows:

Authors.

Professor Evelyn Abbott;

President Charles Kendall Adams;

Professor Herbert B. Adams;

Professor Joseph H. Allen;

Sir William Anson, Bart.;

Reverend Henry M. Baird;

Mr. Hubert Howe Bancroft;

Honorable S. G. W. Benjamin;

Mr. Walter Besant;

Professor Albert S. Bolles;

John G. Bourinot, F. S. S.;

Mr. Henry Bradley;

Reverend James Franck Bright;

Daniel G. Brinton, M. D.;

Professor William Hand Browne;

Professor George Bryce;

Right Honorable James Bryce, M. P.;

J. B. Bury, M. A.;

Mr. Lucien Carr;

Gen. Henry B. Carrington;

Mr. John D. Champlin, Jr.;

Mr. Charles Carleton Coffin;

Honorable Thomas M. Cooley;

Professor Henry Coppée;

Reverend Sir George W. Cox, Bart.;

Gen. Jacob Dolson Cox;

Mrs. Cox (for "'Three Decades of Federal Legislation," by the

late Honorable Samuel S. Cox);

Professor Thomas F. Crane;

Right Reverend Mandell Creighton, Bishop of Peterborough;

Honorable J. L. M. Curry;

Honorable George Ticknor Curtis;

Professor Robert K. Douglas;

J. A. Doyle, M. A.;

Mr. Samuel Adams Drake;

Sir Mountstuart E. Grant-Duff;

Honorable Sir Charles Gaven Duffy;

Mr. Charles Henry Eden;

Mr. Henry Sutherland Edwards;

Orrin Leslie Elliott, Ph. D.;

Mr. Loyall Farragut;

The Ven. Frederic William Farrar, Archdeacon of Westminster;

Professor George Park Fisher;

Professor John Fiske;

Mr. William. E. Foster;

Professor William Warde Fowler;

Professor Edward A. Freeman;

Professor James Anthony Froude;

Mr. James Gairdner;

Arthur Gilman, M. A.;

Mr. Parke Godwin;

Mrs. M. E. Gordon (for the "History of the Campaigns of the

Army of Virginia under Gen. Pope," by the late Gen. George H.

Gordon);

Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould;

Mr. Ulysses S. Grant, Jr. (for the "Personal Memoirs" of the

late Gen. Grant);

Mrs. John Richard Green (for her own writings and for those

of the late John Richard Green);

William Greswell, M. B.;

Major Arthur Griffiths;

Frederic Harrison, M. A.;

Professor Albert Bushnell Hart;

Mr. William Heaton;

Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson;

Professor B. A. Hinsdale;

Miss Margaret L. Hooper (for the writings of the late

Mr. George Hooper);

Reverend Robert F. Horton;

Professor James K. Hosmer;

Colonel Henry M. Hozier;

Reverend William Hunt;

Sir William Wilson Hunter;

Professor Edmund James;

Mr. Rossiter Johnson;

Mr. John Foster Kirk;

The Very Reverend George William Kitchin, Dean of Winchester;

Colonel Thomas W. Knox;

Mr. J. S. Landon;

Honorable Emily Lawless;

William E. H. Lecky, LL. D., D. C. L.;

Mrs. Margaret Levi (for the "History of British Commerce,"

by the late Dr. Leone Levi);

Professor Charlton T. Lewis;

The Very Reverend Henry George Liddell, Dean of Christ Church, Oxford;

Honorable Henry Cabot Lodge;

Richard Lodge, M. A.;

Reverend W. J. Loftie;

Mrs. Mary S. Long (for the "Life of General Robert E. Lee," by

the late Gen. A. L. Long);

Mrs. Helen Lossing (for the writings of the late Benson J. Lossing);

Charles Lowe, M. A.;

Charles P. Lucas, B. A.;

Justin McCarthy, M. P.;

Professor John Bach McMaster;

Honorable Edward McPherson,

Professor John P. Mahaffy;

Capt. Alfred T. Mahan, U. S. N.;

Colonel George B. Malleson;

Clements R. Markham, C. B., F. R. S.;

Professor David Masson;

The Very Reverend Charles Merivale, Dean of Ely;

Professor John Henry Middleton;

Mr. J. G. Cotton Minchin;

William R. Morfill, M. A.;

Right Honorable John Morley, M. P.;

Mr. John T. Morse, Jr.;

Sir William Muir;

Mr. Harold Murdock;

Reverend Arthur Howard Noll;

Miss Kate Norgate;

C. W. C. Oman, M. A.;

Mr. John C. Palfrey (for "History of New England," by the late

John Gorham Palfrey);

Francis Parkman, LL. D.;

Edward James Payne, M. A.;

Charles Henry Pearson, M. A.;

Mr. James Breck Perkins;

Mrs. Mary E. Phelan (for the "History of Tennessee," by the

late James Phelan);

Colonel George E. Pond;

Reginald L. Poole, Ph. D.;

Mr. Stanley Lane-Poole;

William F. Poole, LL. D.;

Major John W. Powell;

Mr. John W. Probyn;

Professor John Clark Ridpath;

Honorable Ellis H. Roberts;

Honorable Theodore Roosevelt;

Mr. John Codman Ropes;

J. H. Rose, M. A.;

Professor Josiah Royce;

Reverend Philip Schaff;

James Schouler, LL. D.;

Honorable Carl Schurz;

Mr. Eben Greenough Scott;

Professor J. R. Seeley;

Professor Nathaniel Southgate Shaler;

Mr. Edward Morse Shepard;

Colonel M. V. Sheridan (for the "Personal Memoirs" of the

late Gen. Sheridan);

Mr. P. T. Sherman (for the "Memoirs" of the late Gen. Sherman);

Samuel Smiles, LL. D.;

Professor Goldwin Smith;

Professor James Russell Soley;

Mr. Edward Stanwood;

Leslie Stephen, M. A.;

H. Morse Stephens, M. A.;

Mr. Simon Sterne;

Charles J. Stillé, LL. D.;

Sir John Strachey;

Right Reverend William Stubbs, Bishop of Peterborough;

Professor William Graham Sumner;

Professor Frank William Taussig;

Mr. William Roscoe Thayer;

Professor Robert H. Thurston;

Mr. Telemachus T. Timayenis;

Henry D. Traill, D. C. L.;

Gen. R. de Trobriand;

Mr. Bayard Tuckerman;

Samuel Epes Turner, Ph. D.;

Professor Herbert Tuttle;

Professor Arminius Vambéry;

Mr. Henri Van Laun;

Gen. Francis A. Walker;

Sir D. Mackenzie Wallace;

Spencer Walpole, LL. D.;

Alexander Stewart Webb, LL. D.;

Mr. J. Talboys Wheeler;

Mr. Arthur Silva White;

Sir Monier Monier-Williams;

Justin Winsor, LL. D.;

Reverend Frederick C. Woodhouse;

John Yeats, LL: D.;

Miss Charlotte M. Yonge.

Publishers.

London:

Messrs.

W. H. Allen & Company;

Asher & Company;

George Bell & Sons;

Richard Bentley & Son;

Bickers & Sons;

A. & C. Black;

Cassell & Company;

Chapman & Hall;

Chatto & Windus:

Thomas De La Rue & Company;

H. Grevel & Company;

Griffith, Farran & Company;

William Heinemann:

Hodder & Stoughton;

Macmillan & Company;

Methuen & Company;

John Murray;

John C. Nimmo;

Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Company;

George Philip & Son;

The Religious Tract Society;

George Routledge & Sons;

Seeley & Company;

Smith, Elder & Company;

Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge;

Edward Stanford;

Stevens & Haynes;

Henry Stevens & Son;

Elliot Stock;

Swan Sonnenschein & Company;

The Times;

T. Fisher Unwin;

Ward, Lock, Bowden & Company;

Frederick Warne & Company;

Williams & Norgate.

New York:

Messrs.

D. Appleton & Company;

Armstrong & Company;

A. S. Barnes & Company;

The Century Company;

T. Y. Crowell & Company;

Derby & Miller:

Dick & Fitzgerald;

Dodd, Mead & Company;

Harper & Brothers;

Henry Holt & Company;

Townsend MacCoun;

G. P. Putnam's Sons;

Anson D. F. Randolph & Company;

D. J. Sadler & Company;

Charles Scribner's Sons;

Charles L. Webster & Company;

Edinburgh:

Messrs.

William Blackwood & Sons;

W. & R. Chambers;

David Douglas;

Thomas Nelson & Sons;

W. P. Nimmo;

Hay & Mitchell;

The Scottish Reformation Society.

Philadelphia:

Messrs.

L. H. Everts & Company;

J. B. Lippincott Company;

Oldach & Company;

Porter & Coates.

Boston:

Messrs.

Estes & Lauriat;

Houghton, Mifflin & Company;

Little, Brown & Company;

D. Lothrop Company;

Roberts Brothers.

Dublin:

Messrs.

James Duffy & Company;

Hodges, Figgis & Company;

J. J. Lalor.

Chicago:

Messrs.

Callaghan & Company;

A. C. McClurg & Company;

Cincinnati:

Messrs.

Robert Clarke & Company;

Jones Brothers Publishing Company;

Hartford, Connecticut:

Messrs.

O. D. Case & Company;

S. S. Scranton & Company;

Albany:

Messrs.

Joel Munsell's Sons.

Cambridge, England:

The University Press.

Norwich, Connecticut:

The Henry Bill Publishing Company;

Oxford:

The Clarendon Press.

Providence, R. I.

J. A. & R. A. Reid.

A list of books quoted from will be given in the final volume. I

am greatly indebted to the remarkable kindness of a number of

eminent historical scholars, who have critically examined the

proof sheets of important articles and improved them by their

suggestions. My debt to Miss Ellen M. Chandler, for assistance

given me in many ways, is more than I can describe.

In my publishing arrangements I have been most fortunate, and I

owe the good fortune very largely to a number of friends, among

whom it is just that I should name Mr. Henry A. Richmond,

Mr. George E. Matthews, and Mr. John G. Milburn. There is no

feature of these arrangements so satisfactory to me as that which

places the publication of my book in the hands of the Company of

which Mr. Charles A. Nichols, of Springfield, Massachusetts, is

the head.

I think myself fortunate, too, in the association of my work with

that of Mr. Alan C. Reiley, from whose original studies and

drawings the greater part of the historical maps in these volumes

have been produced.

J. N. Larned.

List Of Maps And Plans.

'Ethnographic map of Modern Europe,'

Preceding the title-page.

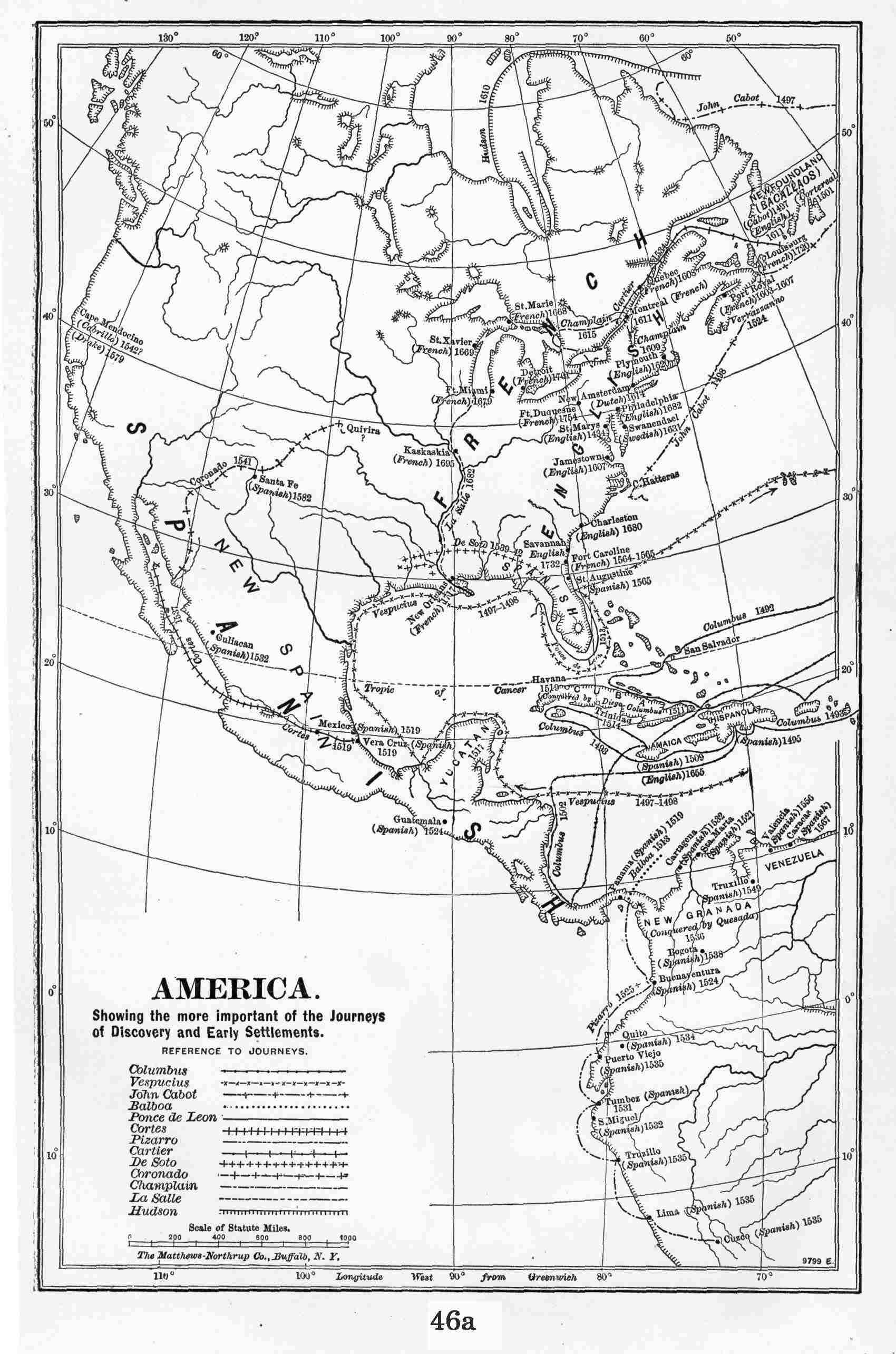

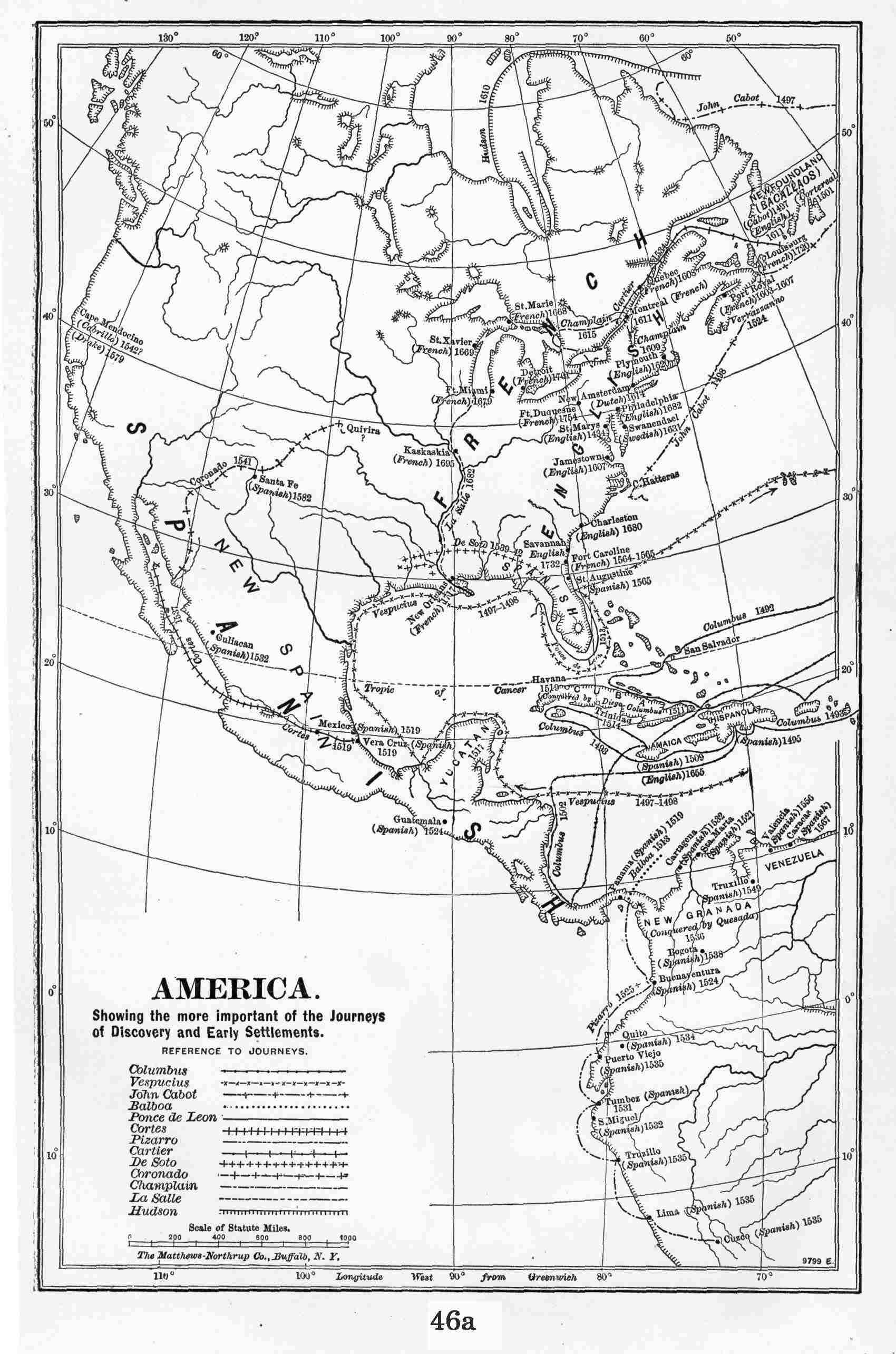

Map of American Discovery and Settlement,

To follow page 46

Plan of Athens, and Harbors of Athens,

On page 145 Plan of Athenian house,

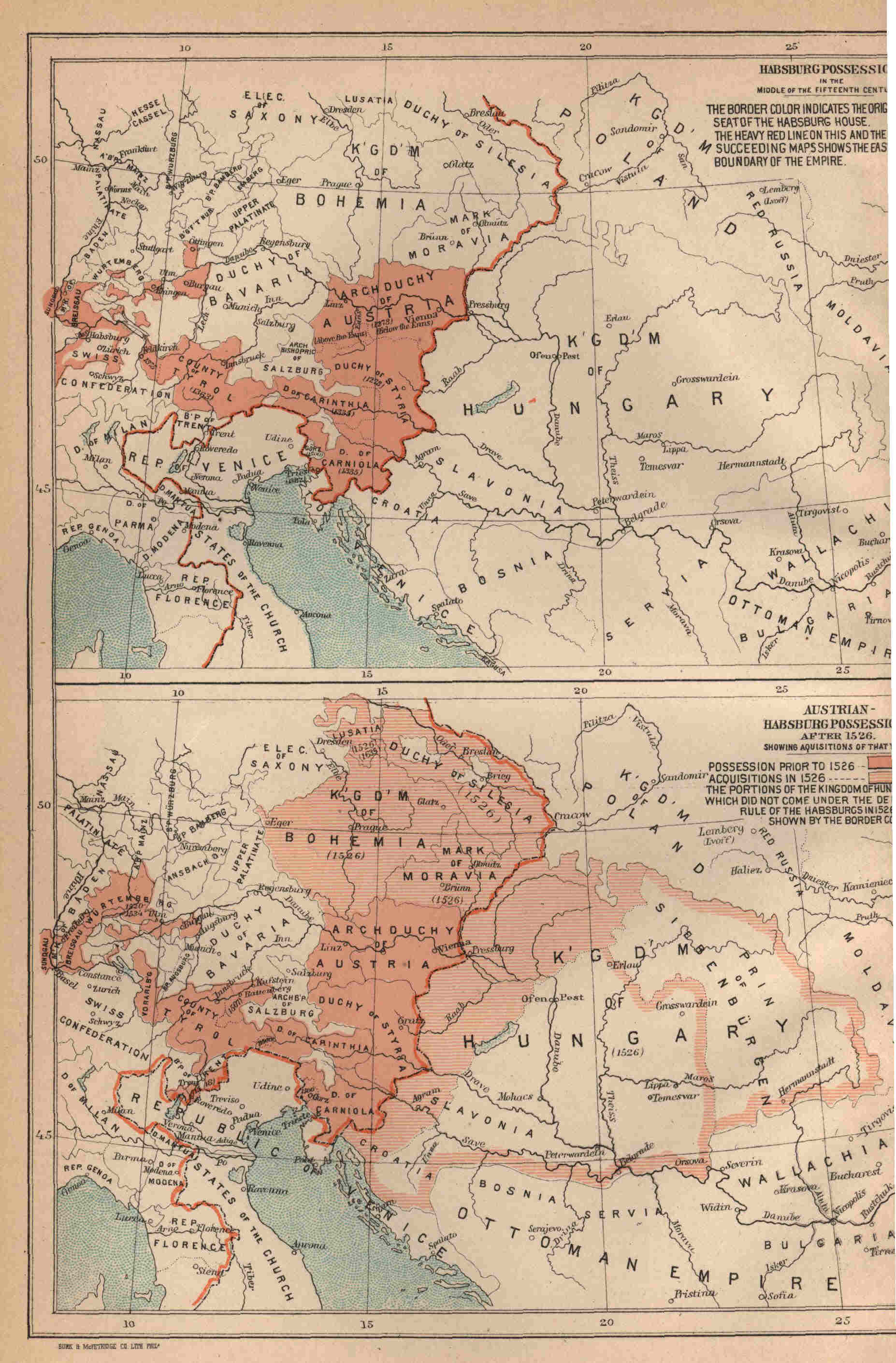

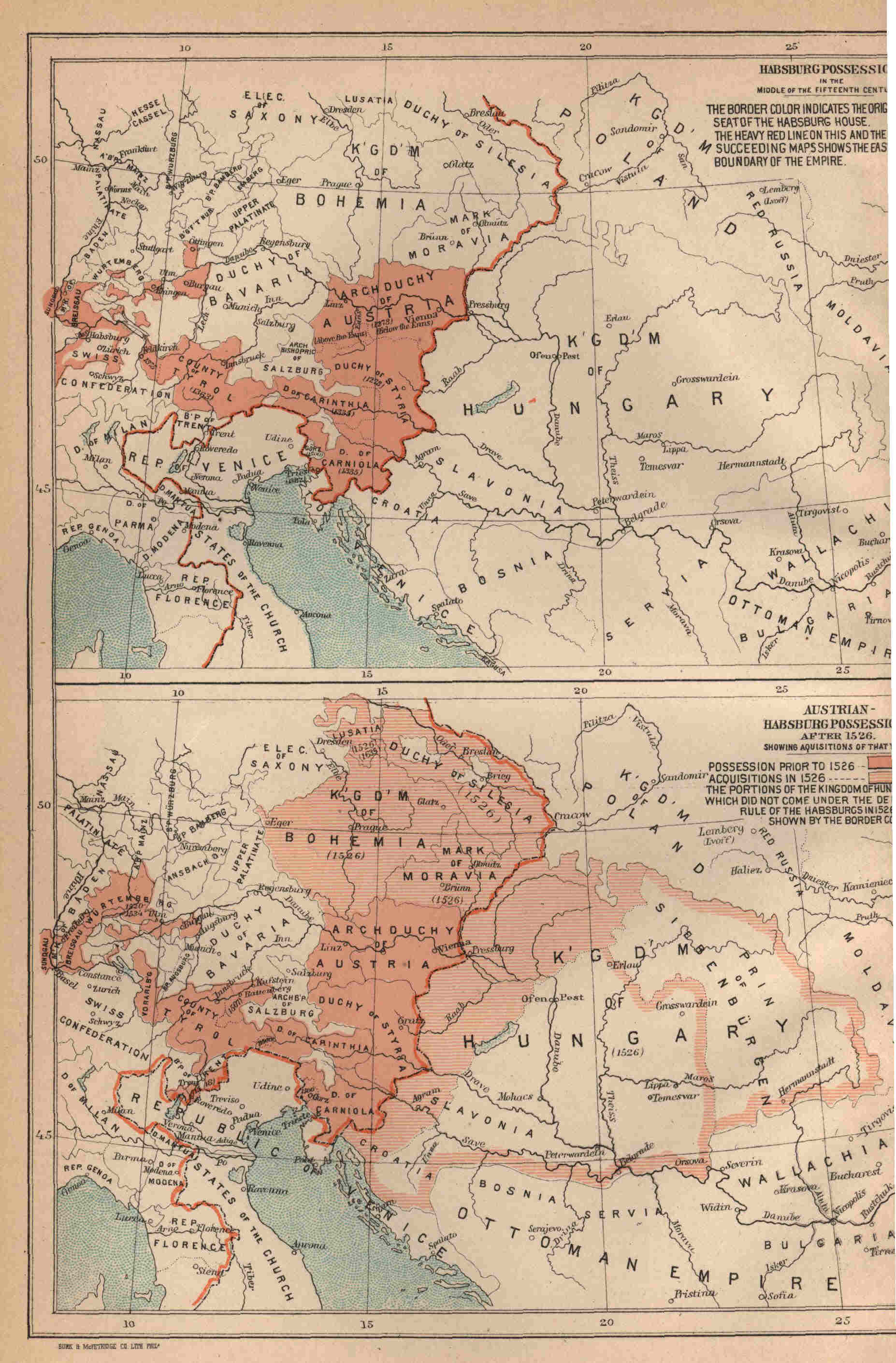

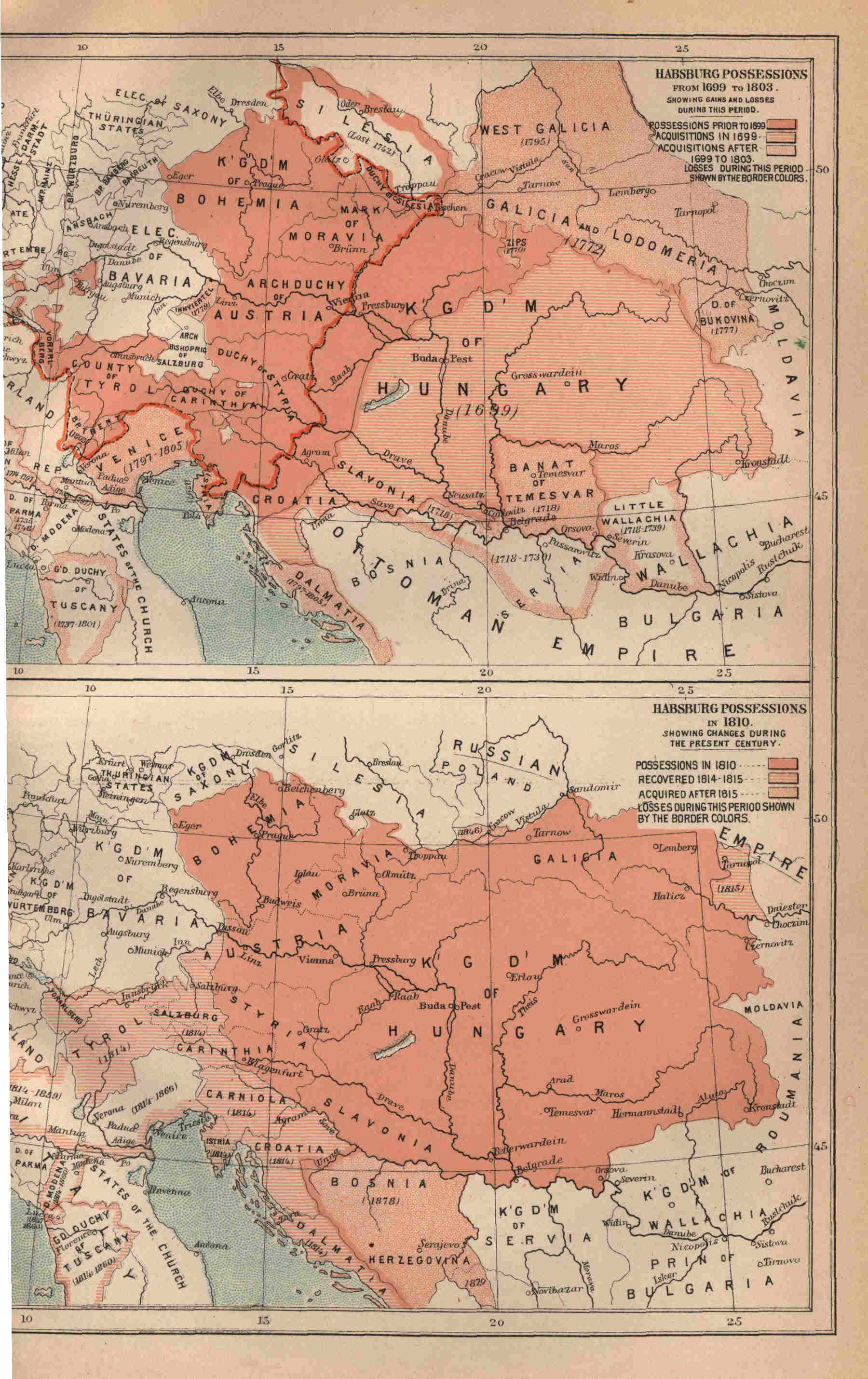

On page 162 Four development maps of Austria,

To follow page 196

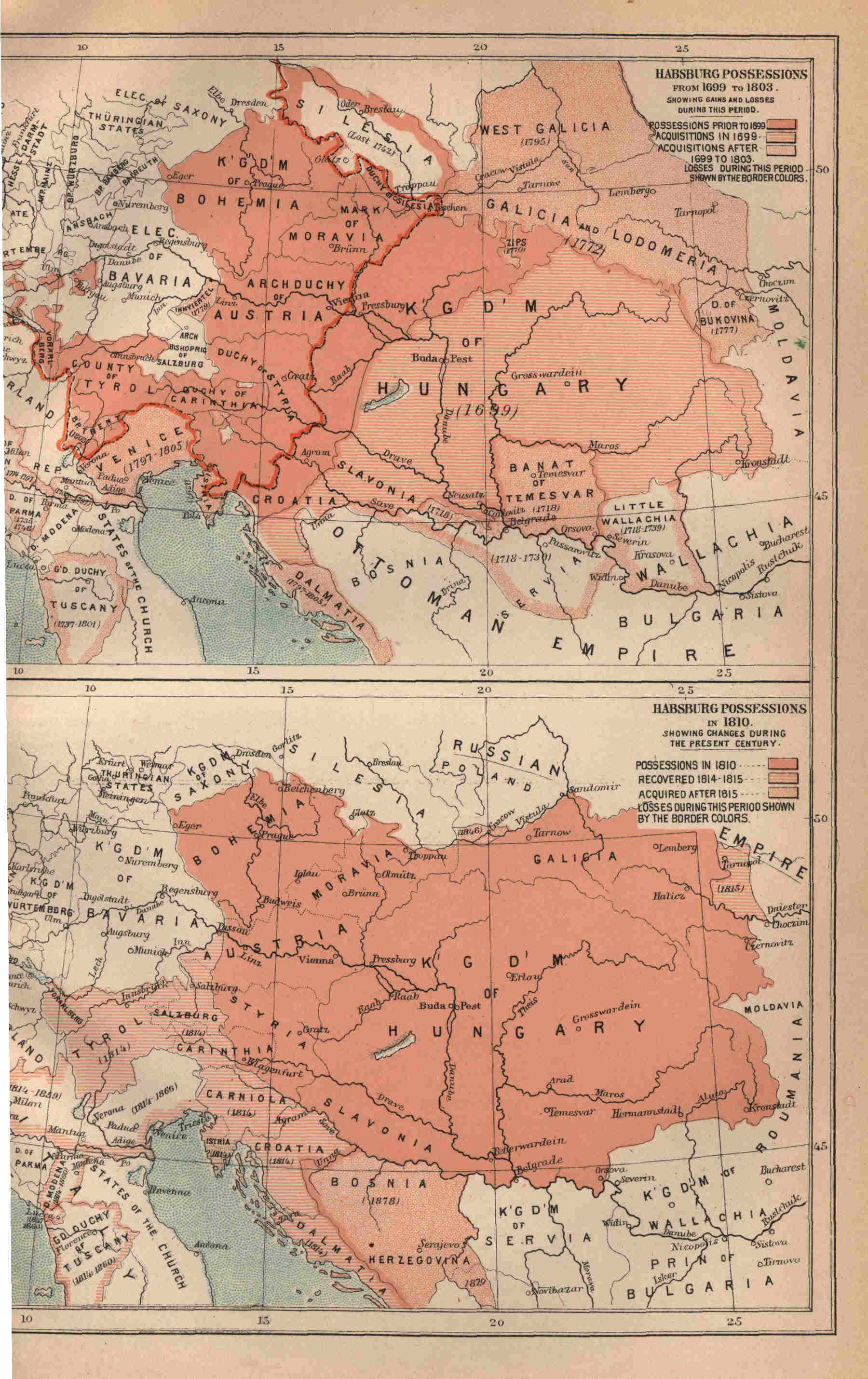

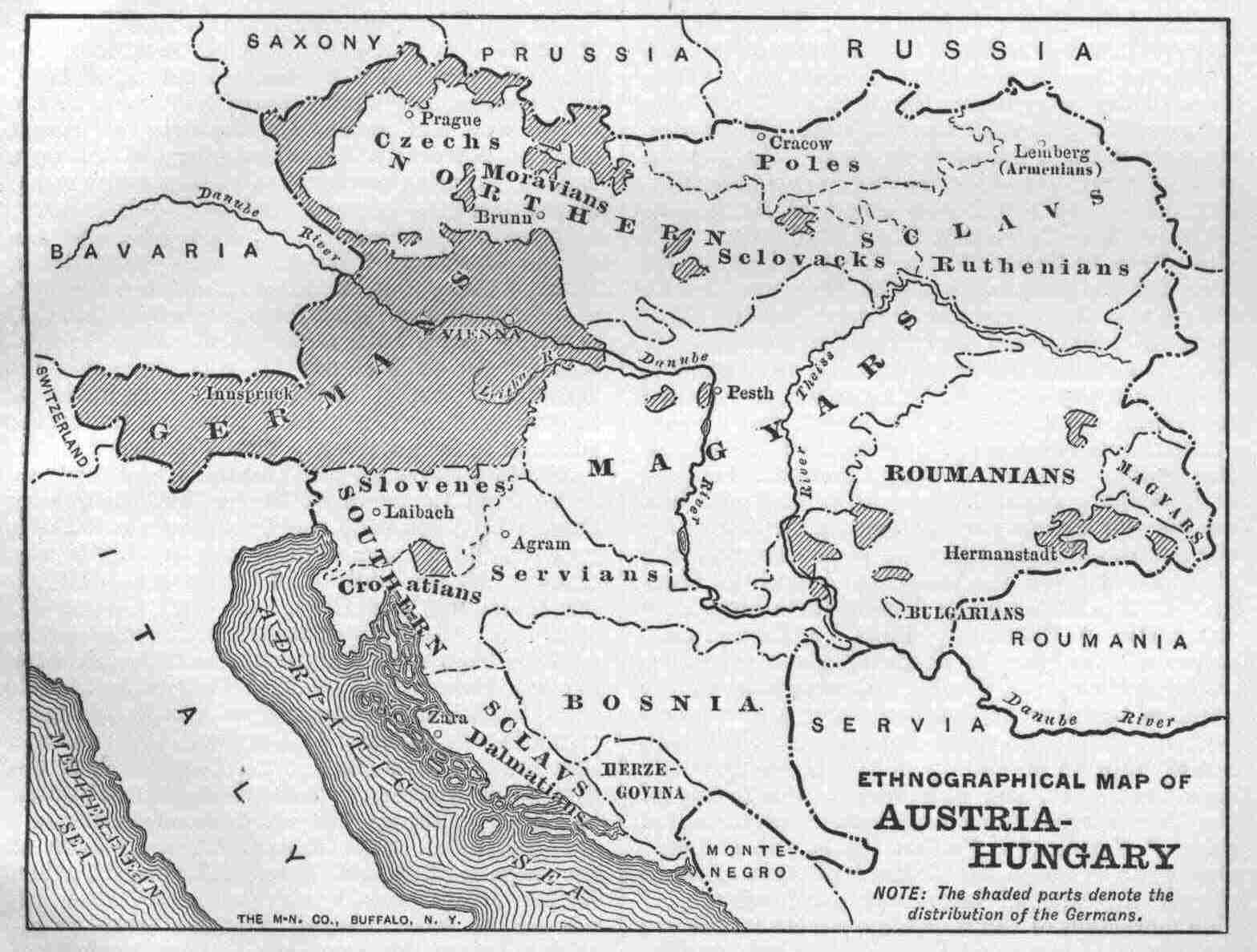

Ethnographic map of Austria-Hungary,

On page 197

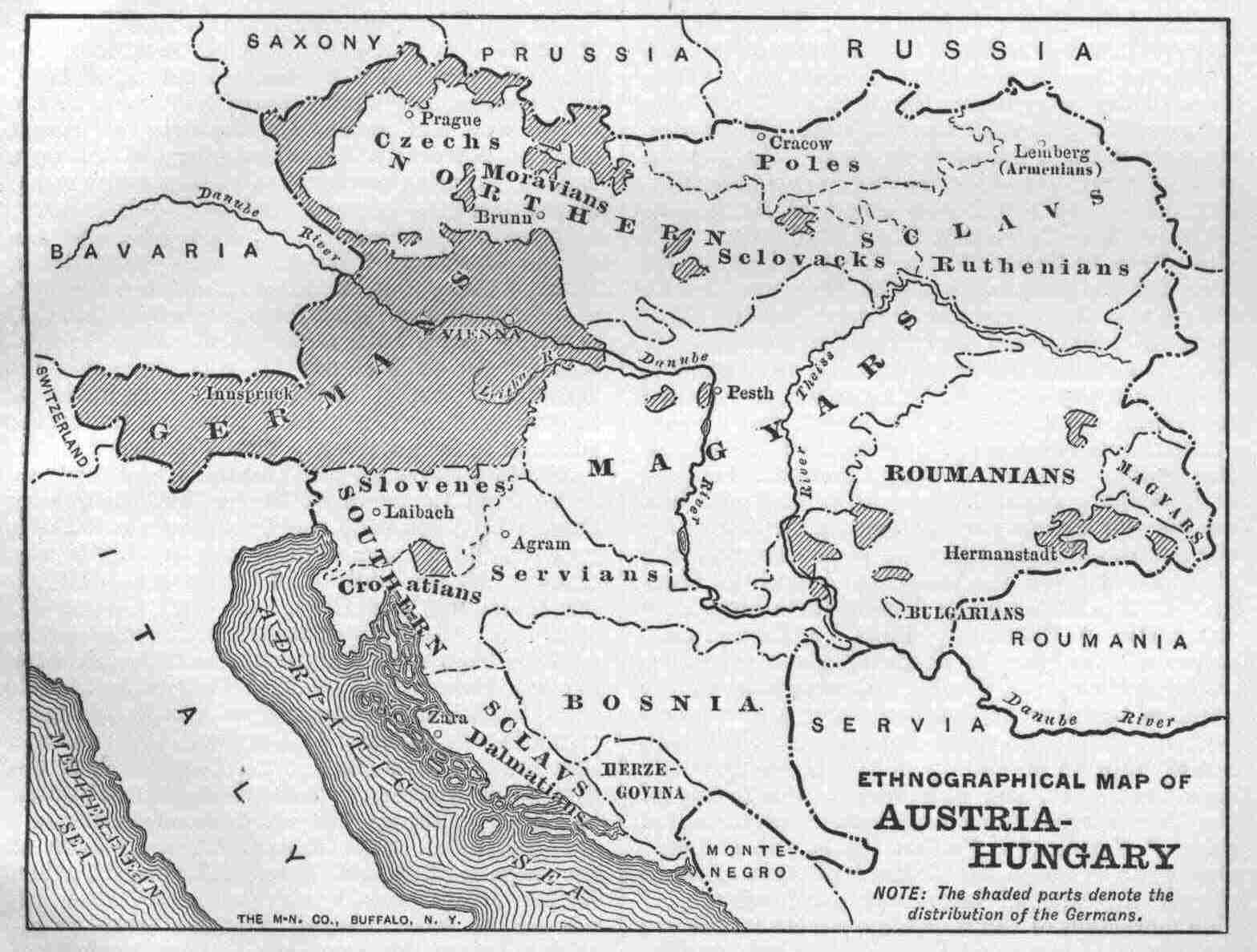

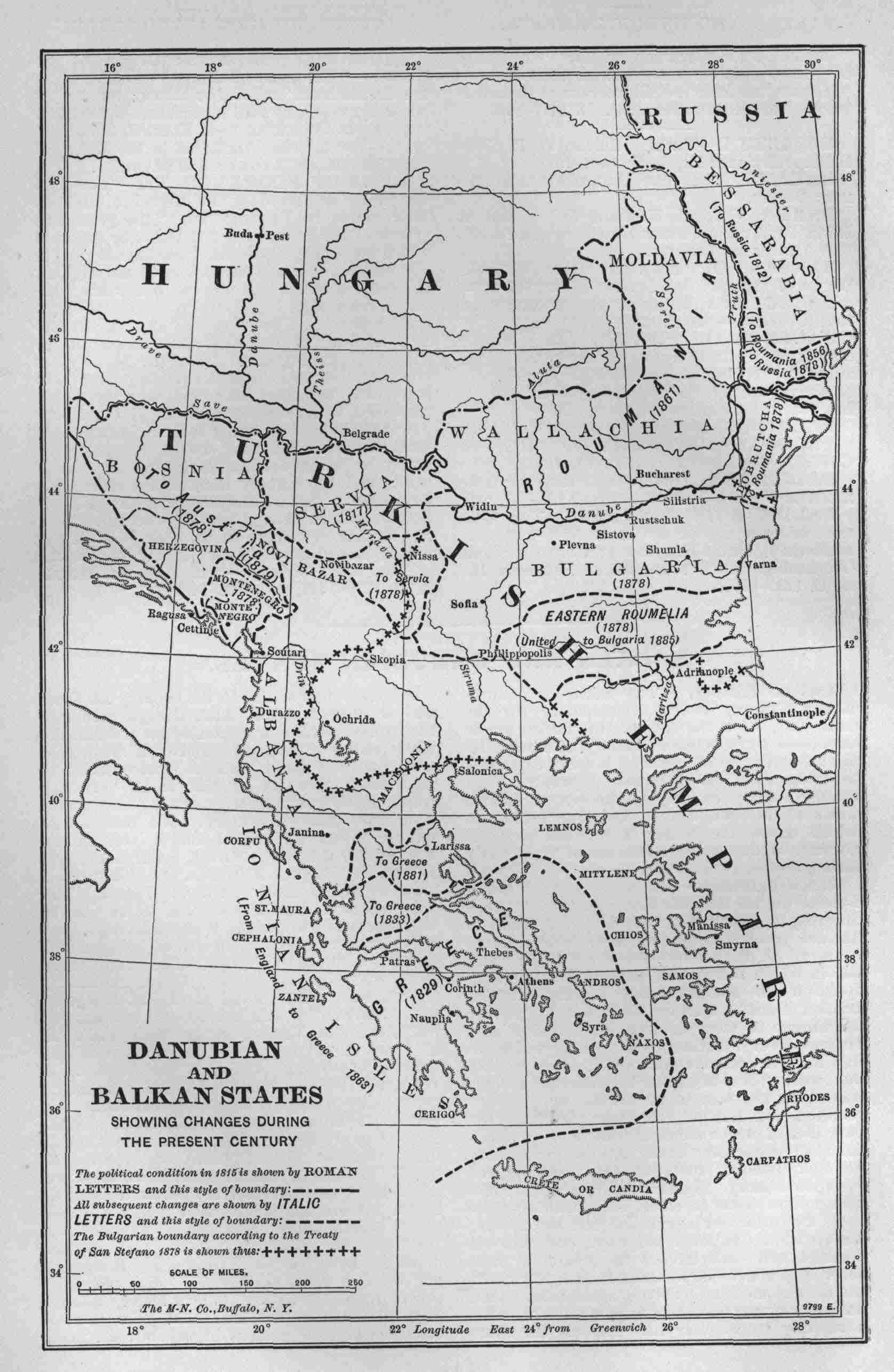

Four development maps of Asia Minor and the Balkan Peninsula,

To follow page 242

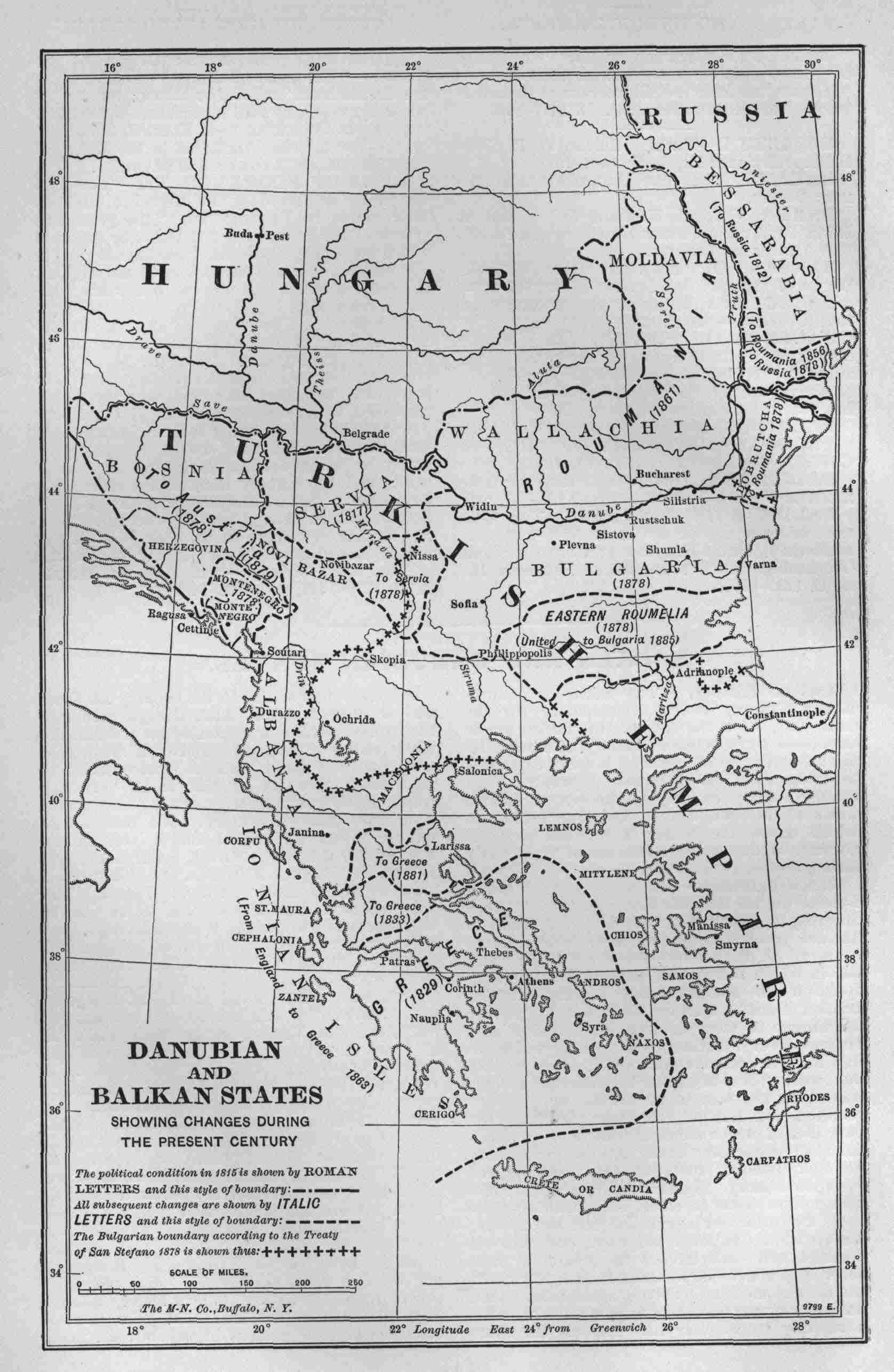

Map of the Balkan and Danubian States, showing changes during

the present century,

On page 244

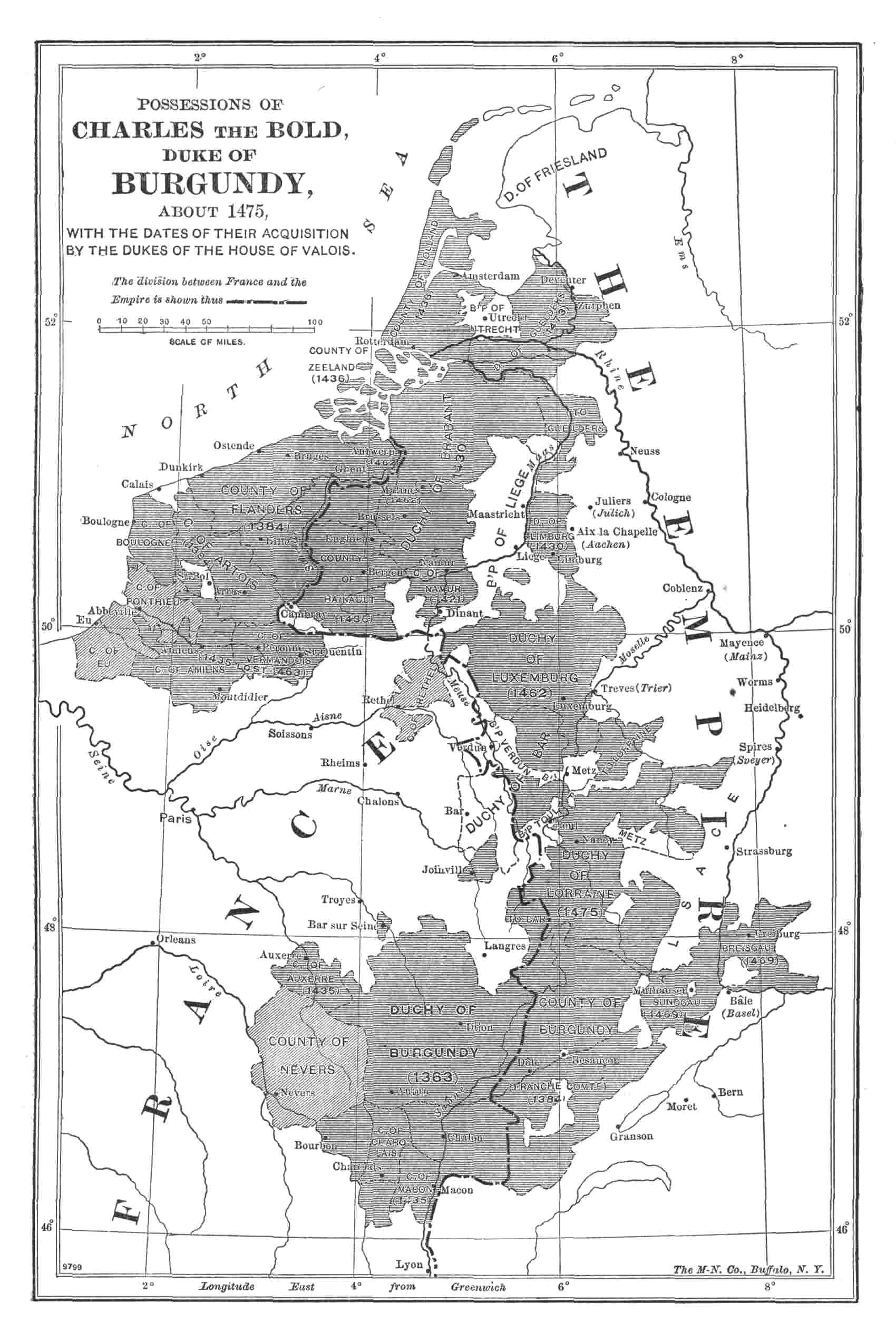

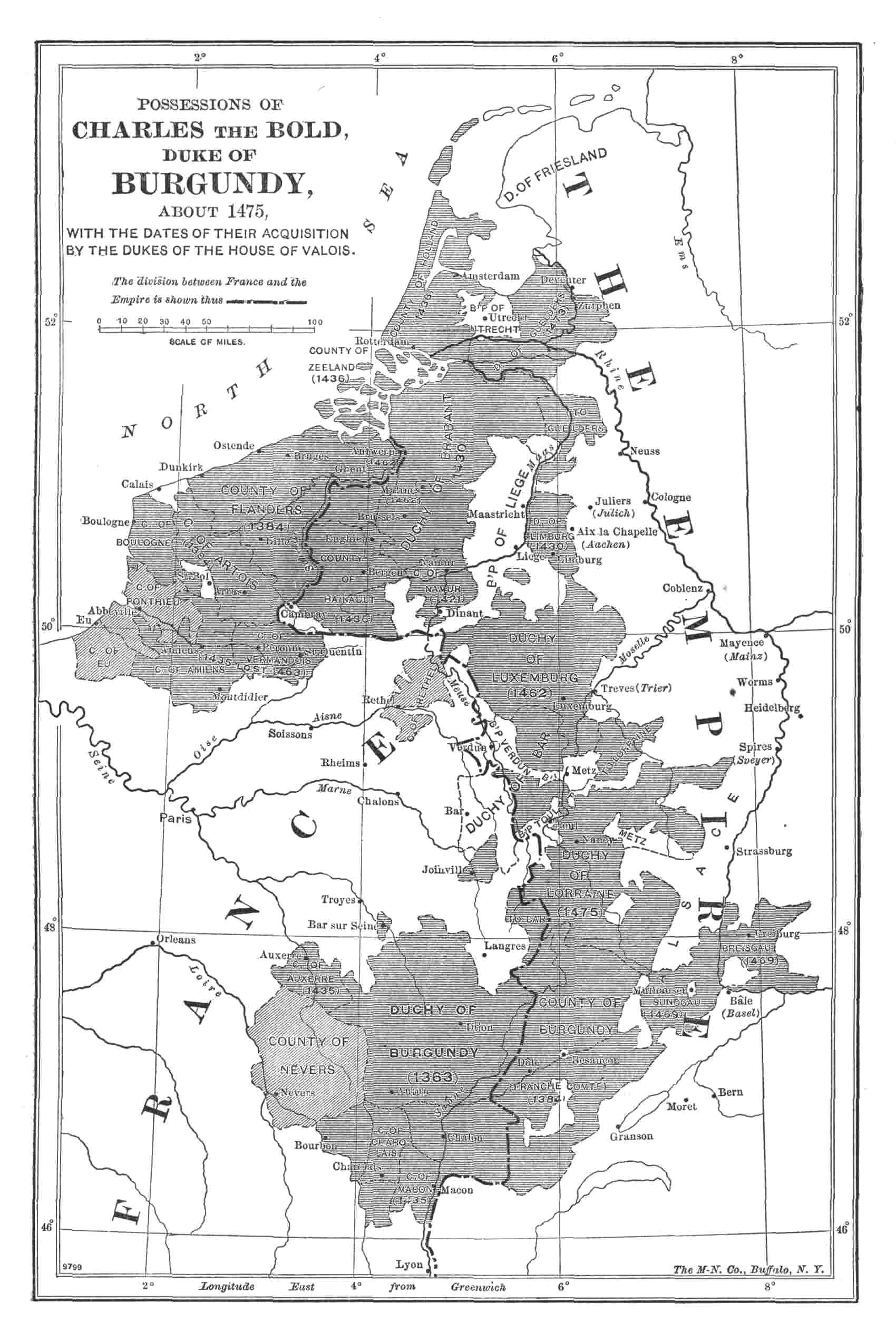

Map of Burgundy under Charles the Bold,

To follow page 332

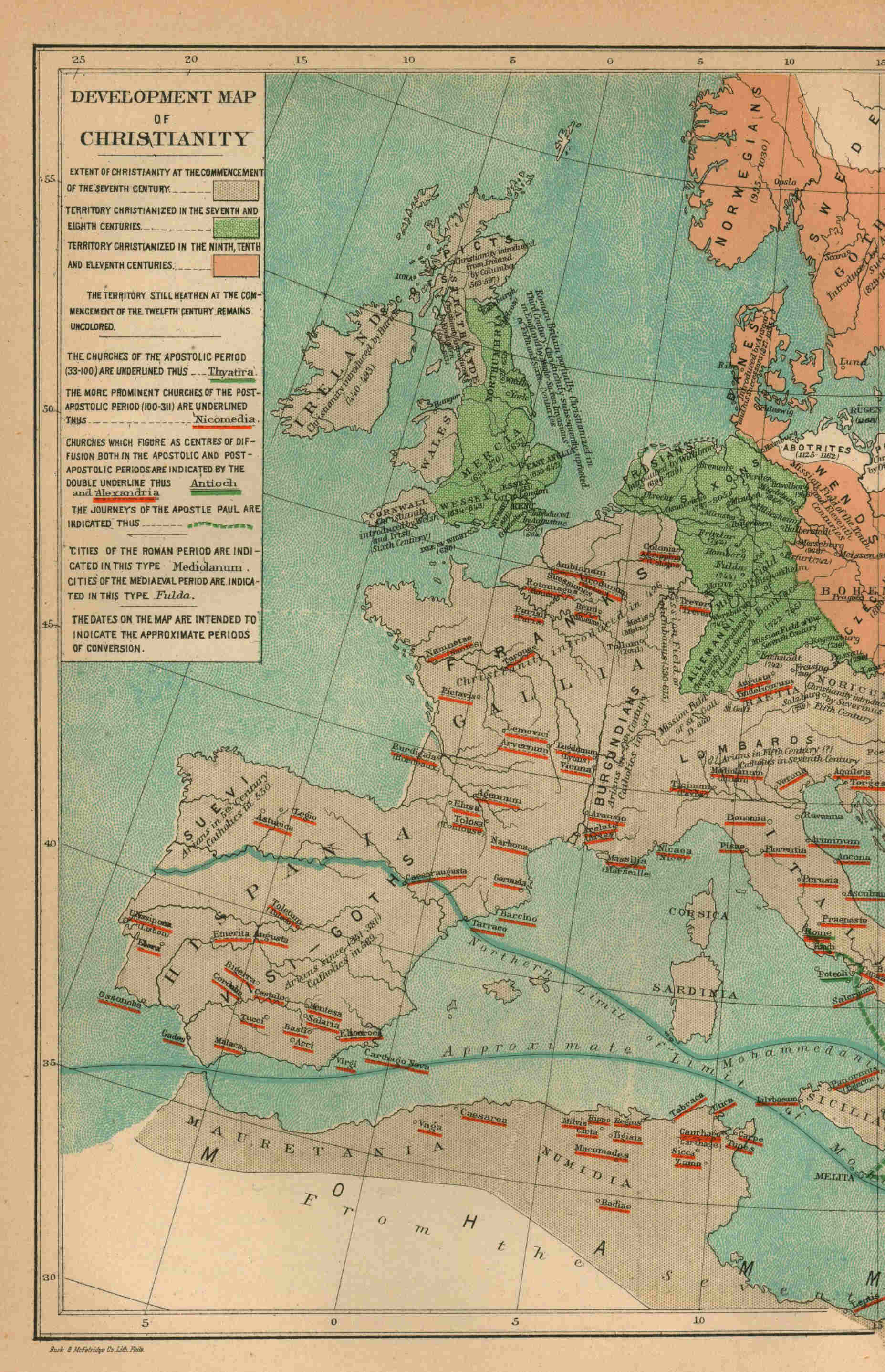

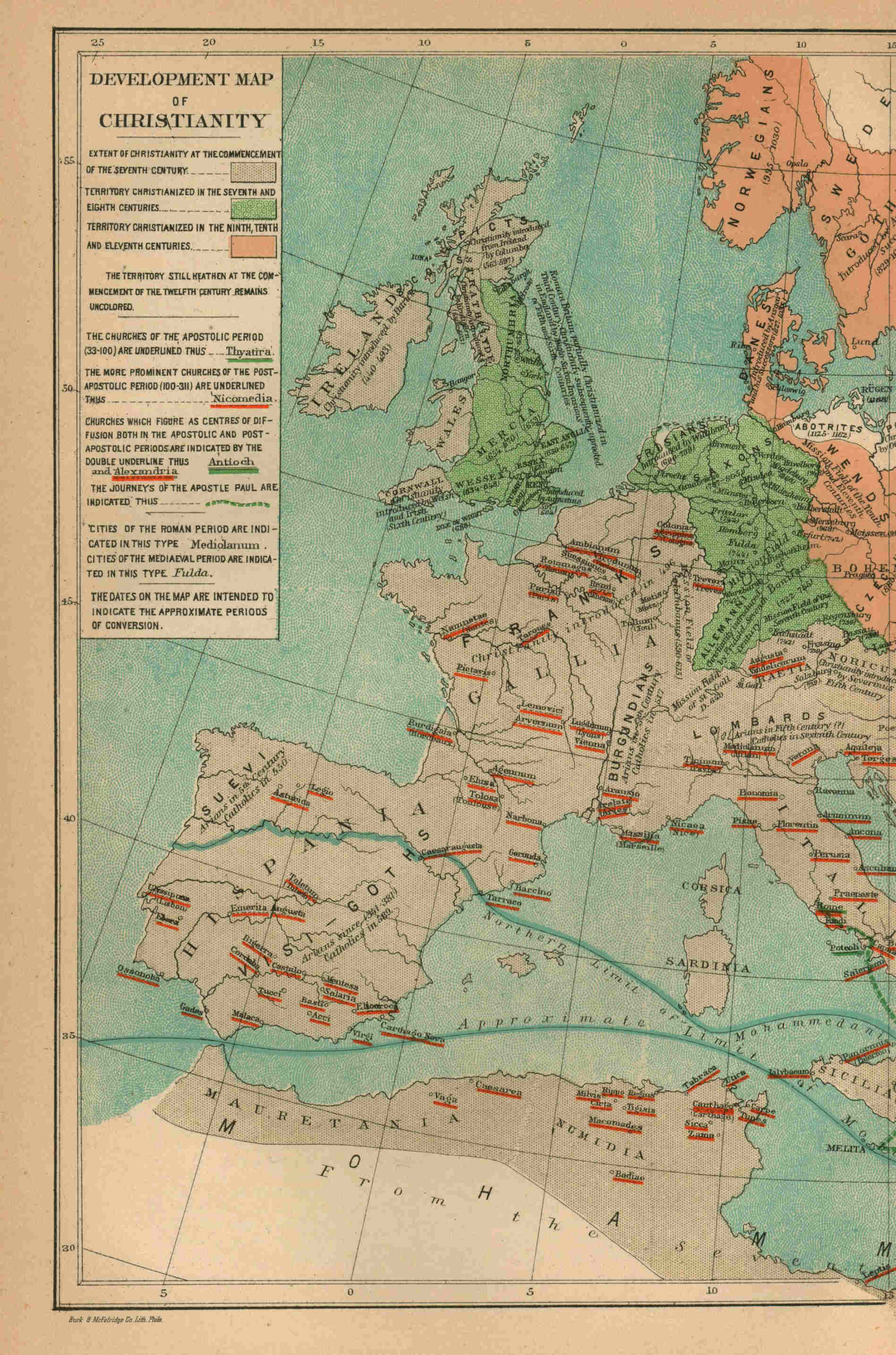

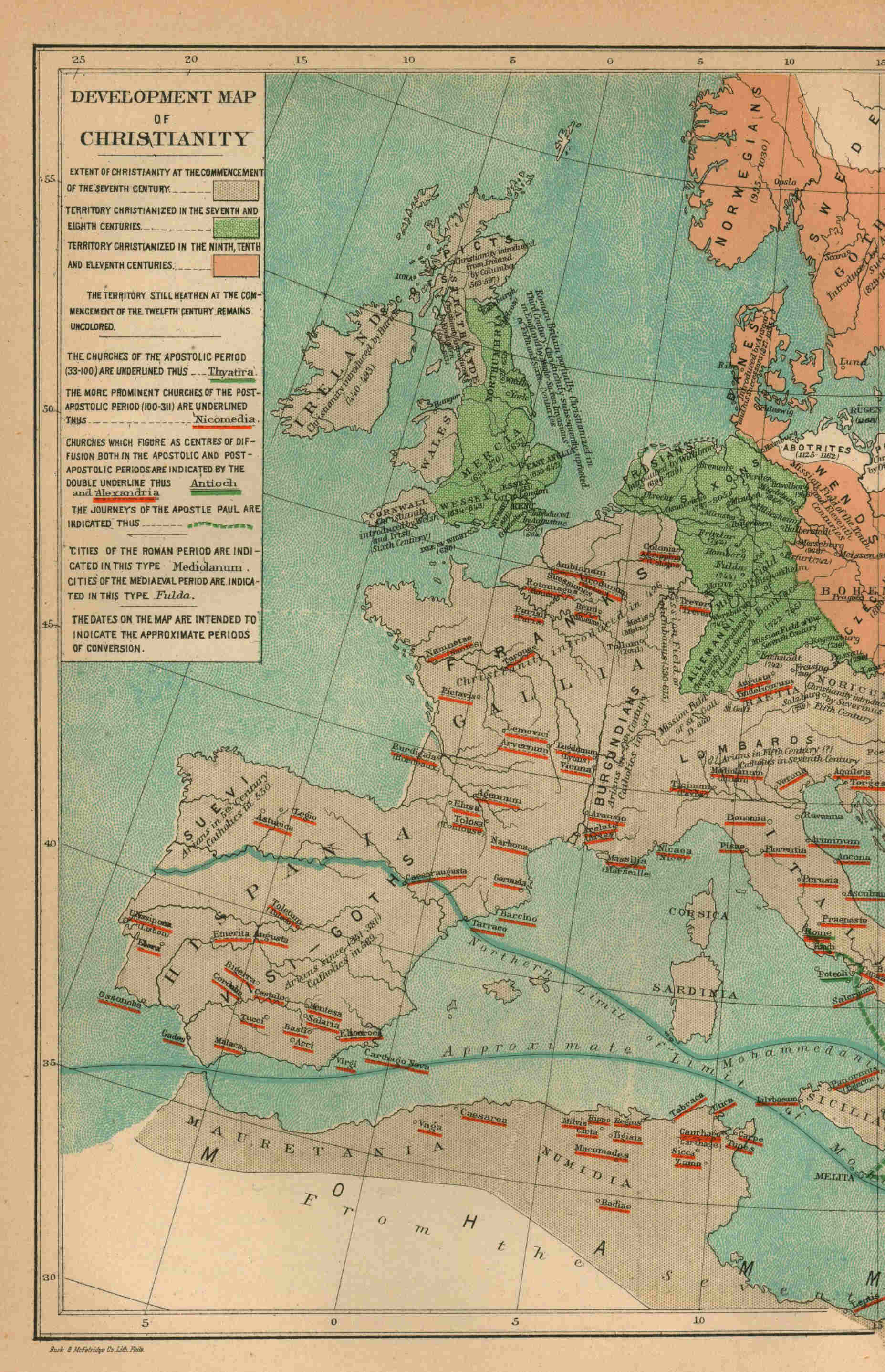

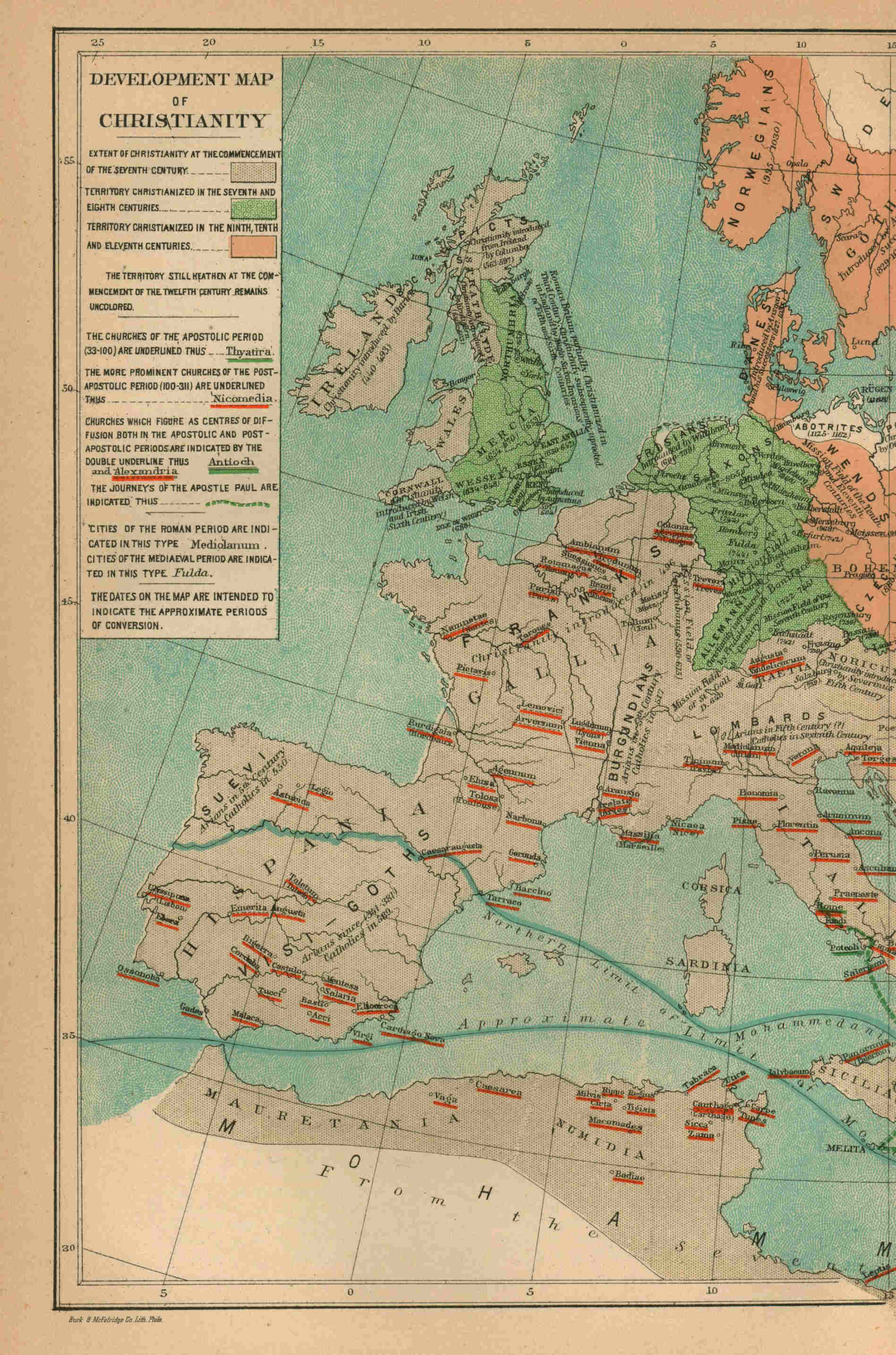

Development map showing the diffusion of Christianity,

To follow page 432

Logical Outlines, In Colors.

Athenian and Greek history, To follow page 144.

Austrian history, To follow page 198.

Chronological Tables.

The Seventeenth Century:

First half and second half, To follow page 208.

To the Peloponnesian War, and Fourth and Third Centuries, B. C.,

To follow page 166.

Appendices To Volume I.

A. Notes to Ethnographic map;

by Mr. A. C. Reiley.

B. Notes to four maps of Asia Minor and the Balkan Peninsula;

by Mr. A. C. Reiley.

C. Notes to map of the Balkan Peninsula in the present century;

by Mr. A. C. Reiley.

D. Notes to map showing the diffusion of Christianity;

Mr. A. C. Reiley.

E. Notes on the American Aborigines;

by Major J. W. Powell and

Mr. J. Owen Dorsey, of the United States Bureau of Ethnology.

F. Bibliography of America

(Discovery, Exploration, Settlement, Archæology, and Ethnology),

and of Austria.

{1}

History For Ready Reference.

A. C. Ante Christum;

used sometimes instead of the more familiar abbreviation,

B. C.--Before Christ.

A. D. Anno Domini;

The Year of Our Lord.

See ERA, CHRISTIAN.

A. E. I. O. U.

"The famous device of Austria, A. E. I. O. U., was first used

by Frederic III. [1440-1493], who adopted it on his plate,

books, and buildings. These initials stand for 'Austriae Est

Imperare Orbi Universo'; or, in German, 'Alles Erdreich Ist

Osterreich Unterthan': a bold assumption for a man who was not

safe in an inch of his dominions."

H. Hallam, The Middle Ages, volume 2, page 89, foot-note.

A. H. Anno Hejiræ.

See ERA, MAHOMETAN.

A. M.

"Anno Mundi;" the Year of the World, or the year from the

beginning of the world, according to the formerly accepted

chronological reckoning of Archbishop Usher and others.

A. U. C., OR U. C.

"Ab urbe condita," from the founding of the city; or "Anno

urbis Conditæ," the year from the founding of the city; the

Year of Rome.

See ROME: B. C. 753.

AACHEN.

See AIX-LA-CHAPELLE.

AARAU, Peace of (1712).

See SWITZERLAND: A. D. 1652-1789.

ABÆ, Oracle of.

See ORACLES OF THE GREEKS.

ABBAS I. (called The Great), Shah of Persia; A. D. 1582-1627

Abbas II., A. D. 1641-1666.

Abbas III., A. D. 1732-1736.

ABBASSIDES, The rise, decline and fall of the.

See MAHOMETAN CONQUEST, &c.: A. D. 715-750; 763; and 815-945;

also BAGDAD: A. D. 1258.

ABBEY.--ABBOT.--ABBESS.

See MONASTERY.

ABDALLEES, The.

See INDIA: A. D. 1747-1761.

ABDALMELIK, Caliph, A. D. 684-705.

ABD-EL-KADER,

The War of the French in Algiers with.

See BARBARY STATES: A. D. 1830-1846.

ABDICATIONS.

Alexander, Prince of Bulgaria.

See BULGARIA: A. D. 1878-1886.

Amadeo of Spain.

See SPAIN: A. D. 1866-1873.

Charles IV. and Ferdinand VII. of Spain.

See SPAIN: A. D. 1807-1808.

Charles V. Emperor.

See GERMANY: A. D. 1552-1561,

and NETHERLANDS: A. D. 1555.

Charles X. King of France.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1815-1830.

Charles Albert, King of Sardinia.

See ITALY: A. D. 1848-1849.

Christina, Regent of Spain.

See SPAIN: A. D. 1833-1846.

Christina, Queen of Sweden.

See SCANDINAVIAN STATES (SWEDEN): A. D. 1644-1697.

Diocletian, Emperor.

See ROME: A. D. 284-305.

Ferdinand, Emperor of Austria.

See AUSTRIA: A. D. 1848-1849.

Louis Bonaparte, King of Holland.

See NETHERLANDS: A. D. 1806-1810.

Louis Philippe.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1841-1848.

Milan, King of Servia.

See SERVIA: A. D. 1882-1889.

Pedro I., Emperor of Brazil, and King of Portugal.

See PORTUGAL: A. D. 1824-1889,

and BRAZIL: A. D. 1825-1865.

Ptolemy I. of Egypt.

See MACEDONIA, &c.: B. C. 297-280.

Victor Emanuel I.

See ITALY: A. D. 1820-1821.

William I., King of Holland.

See NETHERLANDS: A. D. 1830-1884.

ABDUL-AZIZ, Turkish Sultan, A. D. 1861-1876.

ABDUL-HAMID, Turkish Sultan, A. D. 1774-1789.

Abdul-Hamid II., 1876-.

ABDUL-MEDJID, Turkish Sultan, A. D. 1839-1861.

ABEL, King of Denmark, A. D. 1250-1252.

ABENCERRAGES, The.

See SPAIN: A. D. 1238-1273, and 1476-1492.

ABENSBURG, Battle of.

See GERMANY: A. D. 1809 (JANUARY-JUNE).

ABERCROMBIE'S CAMPAIGN IN AMERICA.

See CANADA (NEW FRANCE): A.D. 1758.

ABERDEEN MINISTRY, The.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1851-1852, and 1855.

ABIPONES, The.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES: PAMPAS TRIBES.

ABJURATION OF HENRY IV.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1591-1593.

ABNAKIS, The.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES: ALGONKIN FAMILY.

ABO, Treaty of (1743).

See RUSSIA: A. D. 1740-1762.

ABOLITIONISM IN AMERICA, The Rise of.

See SLAVERY, NEGRO: A. D. 1828-1832; and 1840-1847.

ABORIGINES, AMERICAN.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES.

ABOUKIR, Naval Battle of (or Battle of the Nile).

See FRANCE: A. D. 1798 (MAY-AUGUST).

Land-battle of (1799).

See FRANCE: A. D. 1798-1799 (AUGUST-AUGUST).

ABRAHAM, The Plains of.

That part of the high plateau of Quebec on which the memorable

victory of Wolfe was won, September 13, 1759. The plain was so

called "from Abraham Martin, a pilot known as Maitre Abraham,

who had owned a piece of land here in the early times of the

colony."

F. Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, volume 2, page 289.

For an account of the battle which gave distinction to the

Plains of Abraham,

See CANADA (NEW FRANCE): A. D. 1759, (JUNE-SEPTEMBER).

ABSENTEEISM IN IRELAND.

In Ireland, "the owners of about one-half the land do not live

on or near their estates, while the owners of about one fourth do

not live in the country. ... Absenteeism is an old evil, and

in very early times received attention from the government.

... Some of the disadvantages to the community arising from

the absence of the more wealthy and intelligent classes are

apparent to everyone. Unless the landlord is utterly

poverty-stricken or very unenterprising, 'there is

a great deal more going on' when he is in the country. ... I

am convinced that absenteeism is a great disadvantage to the

country and the people. ... It is too much to attribute to it

all the evils that have been set down to its charge. It is,

however, an important consideration that the people regard it

as a grievance; and think the twenty-five or thirty millions

of dollars paid every year to these landlords, who are rarely

or never in Ireland, is a tax grievous to be borne."

D. B. King, The Irish Question, pages 5-11.

{2}

ABSOROKOS, OR CROWS, The.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES: SIOUAN FAMILY.

ABU-BEKR, Caliph, A. D. 632-634.

ABU KLEA, Battle of (1885).

See EGYPT: A. D. 1884-1885.

ABUL ABBAS, Caliph, A. D. 750-754.

ABUNA OF ABYSSINIA.

"Since the days of Frumentius [who introduced Christianity

into Abyssinia in the 4th century] every orthodox Primate of

Abyssinia has been consecrated by the Coptic Patriarch of the

church of Alexandria, and has borne the title of Abuna"--or

Abuna Salama, "Father of Peace."

H. M. Hozier, The British Expedition to Abyssinia,

page 4.

ABURY, OR AVEBURY.--STONEHENGE.--CARNAC.

"The numerous circles of stone or of earth in Britain and

Ireland, varying in diameter from 30 or 40 feet up to 1,200,

are to be viewed as temples standing in the closest possible

relation to the burial-places of the dead. The most imposing

group of remains of this kind in this country [England] is

that of Avebury [Abury], near Devizes, in Wiltshire, referred

by Sir John Lubbock to a late stage in the Neolithic or to the

beginning of the bronze period. It consists of a large circle of

unworked upright stones 1,200 feet in diameter, surrounded by

a fosse, which in turn is also surrounded by a rampart of

earth. Inside are the remains of two concentric circles of

stone, and from the two entrances in the rampart proceeded

long avenues flanked by stones, one leading to Beckhampton,

and the other to West Kennett, where it formerly ended in

another double circle. Between them rises Silbury Hill, the

largest artificial mound in Great Britain, no less than 130

feet in height. This group of remains was at one time second

to none, 'but unfortunately for us [says Sir John Lubbock] the

pretty little village of Avebury [Abury], like some beautiful

parasite, has grown up at the expense and in the midst of the

ancient temple, and out of 650 great stones, not above twenty

are still standing. In spite of this it is still to be classed

among the finest ruins in Europe. The famous temple of Stonehenge

on Salisbury Plain is probably of a later date than Avebury,

since not only are some of the stones used in its construction

worked, but the surrounding barrows are more elaborate than

those in the neighbourhood of the latter. It consisted of a

circle 100 feet in diameter, of large upright blocks of sarsen

stone, 12 feet 7 inches high, bearing imposts dovetailed into

each other, so as to form a continuous architrave. Nine feet

within this was a circle of small foreign stones ... and

within this five great trilithons of sarsen stone, forming a

horse-shoe; then a horse-shoe of foreign stones, eight feet

high, and in the centre a slab of micaceous sandstone called

the altar-stone. ... At a distance of 100 feet from the outer

line a small ramp, with a ditch outside, formed the outer

circle, 300 feet in diameter, which cuts a low barrow and

includes another, and therefore is evidently of later date

than some of the barrows of the district."

W. B. Dawkins; Early Man in Britain, chapter 10.

"Stonehenge ... may, I think, be regarded as a monument of the

Bronze Age, though apparently it was not all erected at one time,

the inner circle of small, unwrought, blue stones being

probably older than the rest; as regards Abury, since the

stones are all in their natural condition, while those of

Stonehenge are roughly hewn, it seems reasonable to conclude

that Abury is the older of the two, and belongs either to the

close of the Stone Age, or to the commencement of that of

Bronze. Both Abury and Stonehenge were, I believe, used as

temples. Many of the stone circles, however, have been proved

to be burial places. In fact, a complete burial place may be

described as a dolmen, covered by a tumulus, and surrounded by

a stone circle. Often, however, we have only the tumulus,

sometimes only the dolmen, and sometimes again only the stone

circle. The celebrated monument of Carnac, in Brittany,

consists of eleven rows of unhewn stones, which differ greatly

both in size and height, the largest being 22 feet above ground,

while some are quite small. It appears that the avenues

originally extended for several miles, but at present they are

very imperfect, the stones having been cleared away in places for

agricultural improvements. At present, therefore, there are

several detached portions, which, however, have the same

general direction, and appear to have been connected together.

... Most of the great tumuli in Brittany probably belong to the

Stone Age, and I am therefore disposed to regard Carnac as

having been erected during the same period."

Sir J. Lubbock, Prehistoric Times, chapter 5.

ABYDOS.

An ancient city on the Asiatic side of the Hellespont,

mentioned in the Iliad as one of the towns that were in

alliance with the Trojans. Originally Thracian, as is

supposed, it became a colony of Miletus, and passed at

different times under Persian, Athenian, Lacedæmonian and

Macedonian rule. Its site was at the narrowest point of the

Hellespont--the scene of the ancient romantic story of Hero

and Leander--nearly opposite to the town of Sestus. It was in

the near neighborhood of Abydos that Xerxes built his bridge

of boats; at Abydos, Alcibiades and the Athenians won an

important victory over the Peloponnesians.

See GREECE: B. C. 480, and 411-407.

ABYDOS, Tablet of.

One of the most valuable records of Egyptian history, found in

the ruins of Abydos and now preserved in the British Museum. It

gives a list of kings whom Ramses II. selected from among his

ancestors to pay homage to. The tablet was much mutilated when

found, but another copy more perfect has been unearthed by M.

Mariette, which supplies nearly all the names lacking on the

first.

F. Lenormant, Manual of Ancient History of the East,

volume 1, book 3.

ABYSSINIA: Embraced in ancient Ethiopia.

See ETHIOPIA.

ABYSSINIA: Fourth Century.

Conversion to Christianity.

"Whatever may have been the effect produced in his native

country by the conversion of Queen Candace's treasurer,

recorded in the Acts of the Apostles [chapter VIII.], it would

appear to have been transitory; and the Ethiopian or

Abyssinian church owes its origin to an expedition made early

in the fourth century by Meropius, a philosopher of Tyre, for

the purpose of scientific inquiry. On his voyage homewards, he

and his companions were attacked at a place where they had

landed in search of water, and all were massacred except two

youths, Ædesius and Frumentius, the relatives and pupils of

Meropius. These were carried to the king of the country, who

advanced Ædesius to be his cup-bearer, and Frumentius to be

his secretary and treasurer. On the death of the king, who

left a boy as his heir, the two strangers, at the request of

the widowed queen, acted as regents of the kingdom until the

prince came of age. Ædesius then returned to Tyre, where he

became a presbyter. Frumentius, who, with the help of such

Christian traders as visited the country, had already

introduced the Christian doctrine and worship into Abyssinia,

repaired to Alexandria, related his story to Athanasius, and

... Athanasius ... consecrated him to the bishoprick of Axum

[the capital of the Abyssinain kingdom]. The church thus

founded continues to this day subject to the see of

Alexandria."

J. C. Robertson, History of the Christian Church,

book 2, chapter 6.

{3}

ABYSSINIA: 6th to 16th Centuries.

Wars in Arabia.

Struggle with the Mahometans.

Isolation from the Christian world.

"The fate of the Christian church among the Homerites in

Arabia Felix afforded an opportunity for the Abyssinians,

under the reigns of the Emperors Justin and Justinian, to show

their zeal in behalf of the cause of the Christians. The

prince of that Arabian population, Dunaan, or Dsunovas, was a

zealous adherent of Judaism; and, under pretext of avenging

the oppressions which his fellow-believers were obliged to

suffer in the Roman empire, he caused the Christian merchants

who came from that quarter and visited Arabia for the purposes

of trade, or passed through the country to Abyssinia, to be

murdered. Elesbaan, the Christian king of Abyssinia, made this

a cause for declaring war on the Arabian prince. He conquered

Dsunovas, deprived him of the government, and set up a

Christian, by the name of Abraham, as king in his stead. But

at the death of the latter, which happened soon after,

Dsunovas again made himself master of the throne; and it was a

natural consequence of what he had suffered, that he now

became a fiercer and more cruel persecutor than he was before.

... Upon this, Elesbaan interfered once more, under the reign

of the emperor Justinian, who stimulated him to the

undertaking. He made a second expedition to Arabia Felix, and

was again victorious. Dsunovas lost his life in the war; the

Abyssinian prince put an end to the ancient, independent

empire of the Homerites, and established a new government

favourable to the Christians."

A. Neander, General History of the Christian Religion

and Church, second period, section 1.

"In the year 592, as nearly as can be calculated from the

dates given by the native writers, the Persians, whose power

seems to have kept pace with the decline of the Roman empire,

sent a great force against the Abyssinians, possessed

themselves once more of Arabia, acquired a naval superiority

in the gulf, and secured the principal ports on either side of

it."

"It is uncertain how long these conquerors retained their

acquisition; but, in all probability their ascendancy gave way

to the rising greatness of the Mahometan power; which soon

afterwards overwhelmed all the nations contiguous to Arabia,

spread to the remotest parts of the East, and even penetrated

the African deserts from Egypt to the Congo. Meanwhile

Abyssinia, though within two hundred miles of the walls of

Mecca, remained unconquered and true to the Christian faith;

presenting a mortifying and galling object to the more zealous

followers of the Prophet. On this account, implacable and

incessant wars ravaged her territories. ... She lost her

commerce, saw her consequence annihilated, her capital

threatened, and the richest of her provinces laid waste. ...

There is reason to apprehend that she must shortly have sunk

under the pressure of repeated invasions, had not the

Portuguese arrived [in the 16th century] at a seasonable

moment to aid her endeavours against the Moslem chiefs."

M. Russell, Nubia and Abyssinia, chapter 3.

"When Nubia, which intervenes between Egypt and Abyssinia,

ceased to be a Christian country, owing to the destruction of

its church by the Mahometans, the Abyssinian church was cut

off from communication with the rest of Christendom. ... They

[the Abyssinians] remain an almost unique specimen of a

semi-barbarous Christian people. Their worship is strangely

mixed with Jewish customs."

H. F. Tozer, The Church and the Eastern Empire, chapter 5.

ABYSSINIA: Fifteenth-Nineteenth Centuries.

European Attempts at Intercourse.

Intrusion of the Gallas.

Intestine conflicts.

"About the middle of the 15th century, Abyssinia came in

contact with Western Europe. An Abyssinian convent was endowed

at Rome, and legates were sent from the Abyssinian convent at

Jerusalem to the council of Florence. These adhered to the

Greek schism. But from that time the Church of Rome made an

impress upon Ethiopia. ... Prince Henry of Portugal ... next

opened up communication with Europe. He hoped to open up a

route from the West to the East coast of Africa [see PORTUGAL:

A. D. 1415-1460], by which the East Indies might be reached

without touching Mahometan territory. During his efforts to

discover such a passage to India, and to destroy the revenues

derived by the Moors from the spice trade, he sent an

ambassador named Covillan to the Court of Shoa. Covillan was

not suffered to return by Alexander, the then Negoos [or

Negus, or Nagash--the title of the Abyssinian sovereign]. He

married nobly, and acquired rich possessions in the country.

He kept up correspondence with Portugal, and urged Prince

Henry to diligently continue his efforts to discover the

Southern passage to the East. In 1498 the Portuguese effected

the circuit of Africa. The Turks shortly afterwards extended

their conquests towards India, where they were baulked by the

Portuguese, but they established a post and a toll at Zeyla,

on the African coast. From here they hampered and threatened

to destroy the trade of Abyssinia," and soon, in alliance with

the Mahometan tribes of the coast, invaded the country. "They

were defeated by the Negoos David, and at the same time the

Turkish town of Zeyla was stormed and burned by a Portuguese

fleet." Considerable intimacy of friendly relations was

maintained for some time between the against the Turks.

{4}

Abyssinians and the Portuguese, who assisted in defending them

"In the middle of the 16th century ... a

migration of Gallas came from the South and swept up to and

over the confines of Abyssinia. Men of lighter complexion and

fairer skin than most Africans, they were Pagan in religion

and savages in customs. Notwithstanding frequent efforts to

dislodge them, they have firmly established themselves. A

large colony has planted itself on the banks of the Upper

Takkazie, the Jidda and the Bashilo. Since their establishment

here they have for the most part embraced the creed of

Mahomet. The province of Shoa is but an outlier of Christian

Abyssinia, separated completely from co-religionist districts

by these Galla bands. About the same time the Turks took a

firm hold of Massowah and of the lowland by the coast, which

had hitherto been ruled by the Abyssinian Bahar Nagash.

Islamism and heathenism surrounded Abyssinia, where the lamp

of Christianity faintly glimmered amidst dark superstition in

the deep recesses of rugged valleys." In 1558 a Jesuit mission

arrived in the country and established itself at Fremona. "For

nearly a century Fremona existed, and its superiors were the

trusted advisors of the Ethiopian throne. ... But the same

fate which fell upon the company of Jesus in more civilized

lands, pursued it in the wilds of Africa. The Jesuit

missionaries were universally popular with the Negoos, but the

prejudice of the people refused to recognise the benefits

which flowed from Fremona." Persecution befell the fathers,

and two of them won the crown of martyrdom. The Negoos,

Facilidas, "sent for a Coptic Abuna [ecclesiastical primate]

from Alexandria, and concluded a treaty with the Turkish

governors of Massowah and Souakin to prevent the passage of

Europeans into his dominions. Some Capuchin preachers, who

attempted to evade this treaty and enter Abyssinia, met with

cruel deaths. Facilidas thus completed the work of the Turks

and the Gallas, and shut Abyssinia out from European influence

and civilization. ... After the expulsion of the Jesuits,

Abyssinia was torn by internal feuds and constantly harassed

by the encroachments of and wars with the Gallas. Anarchy and

confusion ruled supreme. Towns and villages were burnt down,

and the inhabitants sold into slavery. ... Towards the middle

of the 18th century the Gallas appear to have increased

considerably in power. In the intestine quarrels of Abyssinia

their alliance was courted by each side, and in their country

political refugees obtained a secure asylum." During the early

years of the present century, the campaigns in Egypt attracted

English attention to the Red Sea. "In 1804 Lord Valentia, the

Viceroy of India, sent his Secretary, Mr. Salt, into

Abyssinia;" but Mr. Salt was unable to penetrate beyond Tigre.

In 1810 he attempted a second mission and again failed. It was

not until 1848 that English attempts to open diplomatic and

commercial relations with Abyssinia became successful. Mr.

Plowden was appointed consular agent, and negotiated a treaty

of commerce with Ras Ali, the ruling Galla chief."

H. M. Hozier, The British Expedition to Abyssinia,

Introduction.

ABYSSINIA: A. D. 1854-1889.

Advent of King Theodore.

His English captives and the Expedition which released them.

"Consul Plowden had been residing six years at Massowah when

he heard that the Prince to whom he had been accredited, Ras

Ali, had been defeated and dethroned by an adventurer, whose

name, a few years before, had been unknown outside the

boundaries of his native province. This was Lij Kâsa, better

known by his adopted name of Theodore. He was born of an old

family, in the mountainous region of Kwara, where the land

begins to slope downwards towards the Blue Nile, and educated

in a convent, where he learned to read, and acquired a

considerable knowledge of the Scriptures. Kâsa's convent life

was suddenly put an end to, when one of those marauding Galla

bands, whose ravages are the curse of Abyssinia, attacked and

plundered the monastery. From that time he himself took to the

life of a freebooter. ... Adventurers flocked to his standard;

his power continually increased; and in 1854 he defeated Ras

Ali in a pitched battle, and made himself master of central

Abyssinia." In 1855 he overthrew the ruler of Tigre. "He now

resolved to assume a title commensurate with the wide extent

of his dominion. In the church of Derezgye he had himself

crowned by the Abuna as King of the Kings of Ethiopia, taking

the name of Theodore, because an ancient tradition declared

that a great monarch would some day arise in Abyssinia." Mr.

Plowden now visited the new monarch, was impressed with

admiration of his talents and character, and became his

counsellor and friend. But in 1860 the English consul lost his

life, while on a journey, and Theodore, embittered by several

misfortunes, began to give rein to a savage temper. "The

British Government, on hearing of the death of Plowden,

immediately replaced him at Massowah by the appointment of

Captain Cameron." The new Consul was well received, and was

entrusted by the Abyssinian King with a letter addressed to

the Queen of England, soliciting her friendship. The letter,

duly despatched to its destination, was pigeon-holed in the

Foreign Office at London, and no reply to it was ever made.

Insulted and enraged by this treatment, and by other evidences

of the indifference of the British Government to his

overtures, King Theodore, in January, 1864, seized and

imprisoned Consul Cameron with all his suite. About the same

time he was still further offended by certain passages in a

book on Abyssinia that had been published by a missionary

named Stern. Stern and a fellow missionary, Rosenthal with the

latter's wife, were lodged in prison, and subjected to flogging

and torture. The first step taken by the British Government,

when news of Consul Cameron's imprisonment reached England,

was to send out a regular mission to Abyssinia, bearing a

letter signed by the Queen, demanding the release of the

captives. The mission, headed by a Syrian named Rassam, made

its way to the King's presence in January, 1866. Theodore

seemed to be placated by the Queen's epistle and promised

freedom to his prisoners. But soon his moody mind became

filled with suspicions as to the genuineness of Rassam's

credentials from the Queen, and as to the designs and

intentions of all the foreigners who were in his power. He was

drinking heavily at the time, and the result of his "drunken

cogitations was a determination to detain the mission--at any

rate until by their means he should have obtained a supply of

skilled artisans and machinery from England."

{5}

Mr. Rassam and his companions were accordingly put into

confinement, as Captain Cameron had been. But they were

allowed to send a messenger to England, making their situation

known, and conveying the demand of King Theodore that a man be

sent to him "who can make cannons and muskets." The demand was

actually complied with. Six skilled artisans and a civil

engineer were sent out, together with a quantity of machinery

and other presents, in the hope that they would procure the

release of the unfortunate captives at Magdala. Almost a year

was wasted in these futile proceedings, and it was not until

September, 1867, that an expedition consisting of 4,000

British and 8,000 native troops, under General Sir Robert

Napier, was sent from India to bring the insensate barbarian

to terms. It landed in Annesley Bay, and, overcoming enormous

difficulties with regard to water, food-supplies and

transportation, was ready, about the middle of January, 1868,

to start upon its march to the fortress of Magdala, where

Theodore's prisoners were confined. The distance was 400

miles, and several high ranges of mountains had to be passed

to reach the interior table-land. The invading army met with

no resistance until it reached the Valley of the Beshilo, when

it was attacked (April 10) on the plain of Aroge or Arogi, by

the whole force which Theodore was able to muster, numbering a

few thousands, only, of poorly armed men. The battle was

simply a rapid slaughtering of the barbaric assailants, and

when they fled, leaving 700 or 800 dead and 1,500 wounded on

the field, the Abyssinian King had no power of resistance

left. He offered at once to make peace, surrendering all the

captives in his hands; but Sir Robert Napier required an

unconditional submission, with a view to displacing him from

the throne, in accordance with the wish and expectation which

he had found to be general in the country. Theodore refused

these terms, and when (April 13) Magdala was bombarded and

stormed by the British troops--slight resistance being

made--he shot himself at the moment of their entrance to the

place. The sovereignty he had successfully concentrated in

himself for a time was again divided. Between April and June

the English army was entirely withdrawn, and "Abyssinia was

sealed up again from intercourse with the outer world."

Cassell's Illustrated History of England,

volume 9, chapter 28.

"The task of permanently uniting Abyssinia, in which Theodore

failed, proved equally impracticable to John, who came to the

front, in the first instance, as an ally of the British, and

afterwards succeeded to the sovereignty. By his fall (10th

March, 1889) in the unhappy war against the Dervishes or

Moslem zealots of the Soudan, the path was cleared for Menilek

of Shoa, who enjoyed the support of Italy. The establishment

of the Italians on the Red Sea littoral ... promises a new era

for Abyssinia."

T. Nöldeke, Sketches from Eastern History, chapter 9.

ALSO IN

H. A. Stern, The Captive Missionary.

H. M. Stanley, Coomassie and Magdala, part 2.

ACABA, the Pledges of.

See MAHOMETAN CONQUEST: A. D. 609-632.

ACADEMY, The Athenian.

"The Academia, a public garden in the neighbourhood of Athens,

was the favourite resort of Plato, and gave its name to the

school which he founded. This garden was planted with lofty

plane-trees, and adorned with temples and statues; a gentle

stream rolled through it."

G. H. Lewes, Biog. History of Philosophy, 6th Epoch.

The masters of the great schools of philosophy at Athens "chose

for their lectures and discussions the public buildings which

were called gymnasia, of which there were several in different

quarters of the city. They could only use them by the sufferance

of the State, which had built them chiefly for bodily

exercises and athletic feats. ... Before long several of the

schools drew themselves apart in special buildings, and even

took their most familiar names, such as the Lyceum and the

Academy, from the gymnasia in which they made themselves at

home. Gradually we find the traces of some material

provisions, which helped to define and to perpetuate the

different sects. Plato had a little garden, close by the

sacred Eleusinian Way, in the shady groves of the Academy,

which he bought, says Plutarch, for some 3,000 drachmæ. There

lived also his successors, Xenocrates and Polemon. ...

Aristotle, as we know, in later life had taught in the Lyceum,

in the rich grounds near the Ilissus, and there he probably

possessed the house and garden which after his death came into

the hands of his successor, Theophrastus."

W. W. Capes, University life in Ancient Athens,

pages. 31-33.

For a description of the Academy, the Lyceum, and other

gymnasia of Athens.

See GYMNASIA GREEK.

Concerning the suppression of the Academy,

See ATHENS: A. D. 529.

ACADIA.

See NOVA SCOTIA.

ACADIANS, The, and the British Government.

Their expulsion.

See NOVA SCOTIA: A. D. 1713-1730; 1749-1755, and 1755.

ACARNANIANS.

See AKARNANIANS.

ACAWOIOS, The.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES: CARIBS AND THEIR KINDRED.

ACCAD.--ACCADIANS.

See BABYLONIA, PRIMITIVE.

ACCOLADE.

"The concluding sign of being dubbed or adopted into the order

of knighthood was a slight blow given by the lord to the

cavalier, and called the accolade, from the part of the body,

the neck, whereon it was struck. ... Many writers have

imagined that the accolade was the last blow which the soldier

might receive with impunity: but this interpretation is

not correct, for the squire was as jealous of his honour as

the knight. The origin of the accolade it is impossible to

trace, but it was clearly considered symbolical of the

religious and moral duties of knighthood, and was the only

ceremony used when knights were made in places (the field of

battle, for instance), where time and circumstances did not

allow of many ceremonies."

C. Mills, History of Chivalry, page 1, 53, and foot-note.

ACHÆAN CITIES, League of the.

This, which is not to be confounded with the "Achaian League"

of Peloponnesus, was an early League of the Greek settlements

in southern Italy, or Magna Græca. It was "composed of the

towns of Siris, Pandosia, Metabus or Metapontum, Sybaris with

its offsets Posidonia and Laus, Croton, Caulonia, Temesa,

Terina and Pyxus. ... The language of Polybius regarding the

Achæan symmachy in the Peloponnesus may be applied also to

these Italian Achæans; 'not only did they live in federal and

friendly communion, but they made use of the same laws, and

the same weights, measures and coins, as well as of

the same magistrates, councillors and judges.'"

T. Mommsen, History of Rome, book 1, chapter 10.

{6}

ACHÆAN LEAGUE.

See GREECE: B. C. 280-146.

ACHÆMENIDS, The.

The family or dynastic name (in its Greek form) of the kings

of the Persian Empire founded by Cyrus, derived from an

ancestor, Achæmenes, who was probably a chief of the Persian

tribe of the Pasargadæ. "In the inscription of Behistun, King

Darius says: 'From old time we were kings; eight of my family

have been kings, I am the ninth; from very ancient times we

have been kings.' He enumerates his ancestors: 'My father was

Vistaçpa, the father of Vistaçpa was Arsama; the father of

Arsama was Ariyaramna, the father of Ariyaramna was Khaispis,

the father of Khaispis was Hakhamanis; hence we are called

Hakhamanisiya (Achæmenids).' In these words Darius gives the

tree of his own family up to Khaispis; this was the younger

branch of the Achæmenids. Teispes, the son of Achaemenes, had

two sons; the elder was Cambyses (Kambujiya) the younger

Ariamnes; the son of Cambyses was Cyrus (Kurus), the son of

Cyrus was Cambyses II. Hence Darius could indeed maintain that

eight princes of his family had preceded him; but it was not

correct to maintain that they had been kings before him and

that he was the ninth king."

M. Duncker, History of Antiquity, volume 5, book 8, chapter 3.

ALSO IN

G. Rawlinson, Family of the Achæmenidæ, appendix to

book 7 of Herodotus.

See, also, PERSIA, ANCIENT.

ACHAIA:

"Crossing the river Larissus, and pursuing the northern coast

of Peloponnesus south of the Corinthian Gulf, the traveller

would pass into Achaia--a name which designated the narrow

strip of level land, and the projecting spurs and declivities

between that gulf and the northernmost mountains of the

peninsula. ... Achaean cities--twelve in number at least, if

not more--divided this long strip of land amongst them, from

the mouth of the Larissus and the northwestern Cape Araxus on

one side, to the western boundary of the Sikyon territory on

the other. According to the accounts of the ancient legends

and the belief of Herodotus, this territory had been once

occupied by Ionian inhabitants, whom the Achaeans had

expelled."

G. Grote, History of Greece,

part 2, chapter 4 (volume 2).

After the Roman conquest and the suppression of the Achaian

League, the name Achaia was given to the Roman province then

organized, which embraced all Greece south of Macedonia and

Epirus.

See GREECE: B. C. 280-146.

"In the Homeric poems, where ... the 'Hellenes' only appear in

one district of Southern Thessaly, the name Achæans is employed

by preference as a general appelation for the whole race. But

the Achæans we may term, without hesitation, a Pelasgian

people, in so far, that is, as we use this name merely as the

opposite of the term 'Hellenes,' which prevailed at a later

time, although it is true that the Hellenes themselves were

nothing more than a particular branch of the Pelasgian stock.

... [The name of the] Achæans, after it had dropped its

earlier and more universal application, was preserved as the

special name of a population dwelling in the north of the

Peloponnese and the south of Thessaly."

Georg Friedrich Schömann, Antiquity of Greece:

The State, Introduction.

"The ancients regarded them [the Achæans] as a branch of the

Æolians, with whom they afterwards reunited into one national

body, i.e., not as an originally distinct nationality or

independent branch of the Greek people. Accordingly, we hear

neither of an Achæan language nor of Achæan art. A manifest

and decided influence of the maritime Greeks, wherever the

Achæans appear, is common to the latter with the Æolians.

Achæans are everywhere settled on the coast, and are always

regarded as particularly near relations of the Ionians. ...

The Achæans appear scattered about in localities on the coast

of the Ægean so remote from one another, that it is impossible

to consider all bearing this name as fragments of a people

originally united in one social community; nor do they in fact

anywhere appear, properly speaking, as a popular body, as the

main stock of the population, but rather as eminent families,

from which spring heroes; hence the use of the expression

'Sons of the Achæans' to indicate noble descent."

E. Curtius, History of Greece, book 1, chapter 3.

ALSO IN

M. Duncker, History of Greece,

book 1, chapter 2, and book 2, chapter 2.

See, also,

ACHAIA,

and

GREECE: THE MIGRATIONS.

ACHAIA: A. D. 1205-1387.

Mediæval Principality.

Among the conquests of the French and Lombard Crusaders in

Greece, after the taking of Constantinople, was that of a

major part of the Peloponnesus--then beginning to be called

the Morea--by William de Champlitte, a French knight, assisted

by Geffrey de Villehardouin, the younger--nephew and namesake

of the Marshal of Champagne, who was chronicler of the

conquest of the Empire of the East. William de Champlitte was

invested with this Principality of Achaia, or of the Morea, as

it is variously styled. Geffrey Villehardouin represented him

in the government, as his "bailly," for a time, and finally

succeeded in supplanting him. Half a century later the Greeks,

who had recovered Constantinople, reduced the territory of the

Principality of Achaia to about half the peninsula, and a

destructive war was waged between the two races. Subsequently

the Principality became a fief of the crown of Naples and

Sicily, and underwent many changes of possession until the

title was in confusion and dispute between the houses of

Anjou, Aragon and Savoy. Before it was engulfed finally in the

Empire of the Turks, it was ruined by their piracies and

ravages.

G. Finlay, History of Greece from its Conquest by the

Crusaders, chapter 8.

ACHMET I., Turkish Sultan, A. D. 1603-1617.

Achmet II., 1691-1695.

Achmet III., 1703-1730.

ACHRADINA.

A part of the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, known as the

"outer city," occupying the peninsula north of Ortygia, the

island, which was the "inner city."

ACHRIDA, Kingdom of.

After the death of John Zimisces who had reunited Bulgaria to

the Byzantine Empire, the Bulgarians were roused to a struggle

for the recovery of their independence, under the lead of four

brothers of a noble family, all of whom soon perished save

one, named Samuel. Samuel proved to be so vigorous and able a

soldier and had so much success that he assumed presently the

title of king. His authority was established over the greater

part of Bulgaria, and extended into Macedonia, Epirus and

Illyria. He established his capital at Achrida (modern

Ochrida, in Albania), which gave its name to his kingdom. The

suppression of this new Bulgarian monarchy occupied the

Byzantine Emperor, Basil II., in wars from 981 until 1018,

when its last strongholds, including the city of Achrida, were

surrendered to him.

G. Finlay, History of the Byzantine Empire from 716 to

1057, book 2, chapter 2, section 2.

{7}

ACKERMAN, Convention of (1826).

See TURKS: A. D. 1826-1829.

ACOLAHUS, The.

See MEXICO, ANCIENT: THE TOLTEC EMPIRE.

ACOLYTH, The.

See VARANGIAN or WARING GUARD.

ACRABA, Battle of, A. D. 633.

After the death of Mahomet, his successor, Abu Bekr, had to

deal with several serious revolts, the most threatening of

which was raised by one Moseilama, who had pretended, even in

the life-time of the Prophet, to a rival mission of religion.

The decisive battle between the followers of Moseilama and

those of Mahomet was fought at Acraba, near Yemama. The

pretender was slain and few of his army escaped.

Sir W. Muir, Annals of the Early Caliphate, chapter 7.

ACRABATTENE, Battle of.

A sanguinary defeat of the Idumeans or Edomites by the Jews

under Judas Maccabæus, B. C. 164.

Josephus, Antiquity of the Jews, book 12, chapter 8.

ACRAGAS.

See AGRIGENTUM.

ACRE (St. Jean d'Acre, or Ptolemais): A. D. 1104.

Conquest, Pillage and Massacre by the Crusaders and Genoese.

See CRUSADES: A. D. 1104-1111.

ACRE: A. D.1187.

Taken from the Christians by Saladin.

See JERUSALEM: A. D. 1149-1187.

ACRE: A. D. 1189-1191.

The great siege and reconquest by the Crusaders.

See CRUSADES: A. D. 1188-1192.

ACRE: A. D. 1256-1257.

Quarrels and battles between the Genoese and Venetians.

See VENICE: A. D. 1256-1257.

ACRE: A. D. 1291.

The Final triumph of the Moslems.

See JERUSALEM: A. D. 1291.

ACRE: 18th Century.

Restored to Importance by Sheik Daher.

"Acre, or St. Jean d'Acre, celebrated under this name in the

history of the Crusades, and in antiquity known by the name of

Ptolemais, had, by the middle of the 18th century, been almost

entirely forsaken, when Sheik Daher, the Arab rebel, restored

its commerce and navigation. This able prince, whose sway

comprehended the whole of ancient Galilee, was succeeded by

the infamous tyrant, Djezzar-Pasha, who fortified Acre, and

adorned it with a mosque, enriched with columns of antique

marble, collected from all the neighbouring cities."

M. Malte-Brun, System of Univ. Geog., book 28 (volume 1).

ACRE: A. D. 1799.--Unsuccessful Siege by Bonaparte.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1798-1799 (AUGUST-AUGUST).

ACRE: A. D. 1831-1840.

Siege and Capture by Mehemed Ali.

Recovery for the Sultan by the Western Powers.

See TURKS: A. D.1831-1840.

ACROCERAUNIAN PROMONTORY.

See KORKYRA.

ACROPOLIS OF ATHENS, The.

"A road which, by running zigzag up the slope was rendered

practicable for chariots, led from the lower city to the

Acropolis, on the edge of the platform of which stood the

Propylæa, erected by the architect Mnesicles in five years,

during the administration of Pericles. ... On entering through

the gates of the Propylæa a scene of unparalleled grandeur and

beauty burst upon the eye. No trace of human dwellings

anywhere appeared, but on all sides temples of more or less

elevation, of Pentelic marble, beautiful in design and

exquisitely delicate in execution, sparkled like piles of

alabaster in the sun. On the left stood the Erectheion, or

fane of Athena Polias; to the right, that matchless edifice

known as the Hecatompedon of old, but to later ages as the

Parthenon. Other buildings, all holy to the eyes of an

Athenian, lay grouped around these master structures, and, in

the open spaces between, in whatever direction the spectator

might look, appeared statues, some remarkable for their

dimensions, others for their beauty, and all for the legendary

sanctity which surrounded them. No city of the ancient or

modern world ever rivalled Athens in the riches of art. Our

best filled museums, though teeming with her spoils, are poor

collections of fragments compared with that assemblage of gods

and heroes which peopled the Acropolis, the genuine Olympos of

the arts."

J. A. St. John, The Hellenes, book 1, chapter 4.

"Nothing in ancient Greece or Italy could be compared with the

Acropolis of Athens, in its combination of beauty and grandeur,

surrounded as it was by temples and theatres among its rocks,

and encircled by a city abounding with monuments, some of

which rivalled those of the Acropolis. Its platform formed one

great sanctuary, partitioned only by the boundaries of the ...

sacred portions. We cannot, therefore, admit the suggestion of

Chandler, that, in addition to the temples and other monuments on

the summit, there were houses divided into regular streets.

This would not have been consonant either with the customs or

the good taste of the Athenians. When the people of Attica

crowded into Athens at the beginning of the Peloponnesian war,

and religious prejudices gave way, in every possible case, to the

necessities of the occasion, even then the Acropolis remained

uninhabited. ... The western end of the Acropolis, which

furnished the only access to the summit of the hill, was one

hundred and sixty eight feet in breadth, an opening so narrow

that it appeared practicable to the artists of Pericles to

fill up the space with a single building which should serve

the purpose of a gateway to the citadel, as well as of a

suitable entrance to that glorious display of architecture and

sculpture which was within the inclosure. This work [the

Propylæa], the greatest production of civil architecture in

Athens, which rivalled the Parthenon in felicity of execution,

surpassed it in boldness and originality of design. ... It may be

defined as a wall pierced with five doors, before which on

both sides were Doric hexastyle porticoes."

W. M. Leake, Topography of Athens, section 8.

See, also, ATTICA.

ACT OF ABJURATION, The.

See NETHERLANDS: A. D. 1577-1581.

ACT OF MEDIATION, The.

See SWITZERLAND: A. D. 1803-1848.

ACT OF SECURITY.

See SCOTLAND: A. D. 1703-1704.

ACT OF SETTLEMENT (English).

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1701.

ACT OF SETTLEMENT (Irish).

See IRELAND: A. D. 1660-1665.

{8}

ACT RESCISSORY.

See SCOTLAND; A. D. 1660-1666.

ACTIUM: B. C. 434.

Naval Battle of the Greeks.

A defeat inflicted upon the Corinthians by the Corcyrians, in

the contest over Epidamnus which was the prelude to the

Peloponnesian War.

E. Curtius, History of Greece, book 4, chapter 1.

ACTIUM: B. C. 31.

The Victory of Octavius.

See ROME: B. C. 31.

ACTS OF SUPREMACY.

See SUPREMACY, ACTS OF;

and ENGLAND: A. D. 1527-1534; and 1559.

ACTS OF UNIFORMITY.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1559 and 1662-1665.

ACULCO, Battle of (1810).

See MEXICO: A. D. 1810-1819.

ACZ, Battle of (1849).

See AUSTRIA, A. D. 1848-1849.

ADALOALDUS, King of the Lombards, A. D. 616-626.

ADAMS, John, in the American Revolution.

See

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1774 (MAY-JUNE);

1774 (SEPTEMBER); 1775 (MAY-AUGUST);

1776 (JANUARY-JUNE), 1776 (JULY).

In diplomatic service.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1782 (APRIL); 1782 (SEPTEMBER-NOVEMBER).

Presidential election and administration.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A.D. 1796-1801.

ADAMS, John Quincy.

Negotiation of the Treaty of Ghent.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1814 (DECEMBER).

Presidential election and administration.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1824-1829.

ADAMS, Samuel, in and after the American Revolution.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1772-1773;

1774 (SEPTEMBER); 1775(MAY); 1787-1789.

ADDA, Battle of the (A. D. 490).

See ROME: A. D. 488-526.

AD DECIMUS, Battle of (A. D. 533).

See VANDALS: A. D. 533-534.

ADEL.--ADALING.--ATHEL.

"The homestead of the original settler, his house,

farm-buildings and enclosure, 'the toft and croft,' with the

share of arable and appurtenant common rights, bore among the

northern nations [early Teutonic] the name of Odal, or Edhel;

the primitive mother village was an Athelby, or Athelham; the

owner was an Athelbonde: the same word Adel or Athel signified

also nobility of descent, and an Adaling was a nobleman.

Primitive nobility and primitive landownership thus bore the

same name."

William Stubbs, Constitutional History of England,

chapter 3, section 24.

See, also, ALOD, and ETHEL.

ADELAIDE, The founding and naming of.

See AUSTRALIA: A. D. 1800-1840.

ADELANTADOS.-ADELANTAMIENTOS.

"Adelantamientos was an early term for gubernatorial districts

[in Spanish America, the governors bearing the title of

Adelantados], generally of undefined limits, to be extended by

further conquests."

H. H. Bancroft, History of the Pacific States,

volume 6 (Mexico, volume 3), page 520.

ADEODATUS II., Pope, A. D. 672-676.

ADIABENE.

A name which came to be applied anciently to the tract of

country east of the middle Tigris, embracing what was

originally the proper territory of Assyria, together with

Arbelitis. Under the Parthian monarchy it formed a tributary

kingdom, much disputed between Parthia and Armenia. It was

seized several times by the Romans, but never permanently

held.

G. Rawlinson, Sixth Great Oriental Monarchy, page 140.

ADIRONDACKS, The.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES: ADIRONDACKS.

ADIS, Battle of (B. C. 256).

See PUNIC WAR, THE FIRST.

ADITES, The.

"The Cushites, the first inhabitants of Arabia, are known in

the national traditions by the name of Adites, from their

progenitor, who is called Ad, the grandson of Ham."

F. Lenormant, Manual of Ancient History, book 7, chapter 2.

See ARABIA: THE ANCIENT SUCCESSION AND FUSION OF RACES.

ADJUTATORS.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1647 (APRIL-AUGUST).

ADLIYAH, The.

See ISLAM.

ADOLPH (of Nassau), King of Germany, A. D. 1291-1298.

ADOLPHUS FREDERICK, King of Sweden, A. D. 1751-1771.

ADOPTIONISM.

A doctrine, condemned as heretical in the eighth century,

which taught that "Christ, as to his human nature, was not

truly the Son of God, but only His son by adoption." The dogma

is also known as the Felician heresy, from a Spanish bishop,

Felix, who was prominent among its supporters. Charlemagne

took active measures to suppress the heresy.

J. I. Mombert, History of Charles the Great,

book 2, chapter 12.

ADRIA, Proposed Kingdom of.

See ITALY: A. D. 1343-1389.

ADRIAN VI., Pope, A. D. 1522-1523.

ADRIANOPLE.--HADRIANOPLE.

A city in Thrace founded by the Emperor Hadrian and designated

by his name. It was the scene of Constantine's victory over

Licinius in A. D. 323 (see ROME: 'A. D. 305-323), and of the

defeat and death of Valens in battle with the Goths (see GOTHS

(VISIGOTHS): A. D. 378). In 1361 it became for some years the

capital of the Turks in Europe (see TURKS: A. D. 1360-1389).

It was occupied by the Russians in 1829, and again in 1878

(see TURKS: A. D. 1826-1829, and A. D. 1877-1878), and gave

its name to the Treaty negotiated in 1829 between Russia and

the Porte (see GREECE: A. D. 1821-1829).

ADRIATIC, The Wedding of the.

See VENICE: A. D. 1177, and 14TH CENTURY.

ADRUMETUM.

See CARTHAGE, THE DOMINION OF.

ADUATUCI, The.

See BELGÆ.

ADULLAM, Cave of.

When David had been cast out by the Philistines, among whom he

sought refuge from the enmity of Saul, "his first retreat was the

Cave of Adullam, probably the large cavern not far from

Bethlehem, now called Khureitun. From its vicinity to

Bethlehem, he was joined there by his whole family, now

feeling themselves insecure from Saul's fury. ... Besides

these were outlaws from every part, including doubtless some

of the original Canaanites--of whom the name of one at least

has been preserved, Ahimelech the Hittite. In the vast

columnar halls and arched chambers of this subterranean

palace, all who had any grudge against the existing system

gathered round the hero of the coming age."

Dean Stanley, Lectures on the History of the Jewish

Church, lecture 22.

ADULLAMITES, The.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1865-1868.

{9}

ADWALTON MOOR, Battle of (A. D. 1643).

This was a battle fought near Bradford, June 29, 1643, in the

great English Civil War. The Parliamentary forces, under Lord

Fairfax, were routed by the Royalists, under Newcastle.

C. R. Markham, Life of the Great Lord Fairfax, chapter 11.

ÆAKIDS (Æacids).

The supposed descendants of the demi-god Æakus, whose grandson

was Achilles. (See MYRMIDONS.) Miltiades, the hero of Marathon,

and Pyrrhus, the warrior King of Epirus, were among those

claiming to belong to the royal race of Eakids.

ÆDHILING.

See ETHEL.

ÆDILES, Roman.

See ROME: B. C. 494-492.

ÆDUI.--ARVERNI.--ALLOBROGES.

"The two most powerful nations in Gallia were the Ædui [or

Hædui] and the Arverni. The Ædui occupied that part which lies

between the upper valley of the Loire and the Saone, which river

was part of the boundary between them and the Sequani. The

Loire separated the Ædui from the Bituriges, whose chief town

was Avaricum on the site of Bourges. At this time [B. C.121]

the Arverni, the rivals of the Ædui, were seeking the

supremacy in Gallia. The Arverni occupied the mountainous

country of Auvergne in the centre of France and the fertile

valley of the Elaver (Allier) nearly as far as the junction of

the Allier and the Loire. ... They were on friendly terms with

the Allobroges, a powerful nation east of the Rhone, who

occupied the country between the Rhone and the Isara (Isère).

... In order to break the formidable combination of the

Arverni and the Allobroges, the Romans made use of the Ædui,

who were the enemies both of the Allobroges and the Arverni.

... A treaty was made either at this time or somewhat earlier

between the Ædui and the Roman senate, who conferred on their

new Gallic friends the honourable title of brothers and

kinsmen. This fraternizing was a piece of political cant which

the Romans practiced when it was useful."

G. Long, Decline of the Roman Republic, volume 1, chapter 21.

See, also, GAULS.

Ægæ.

See EDESSA (MACEDONIA).

ÆGATIAN ISLES, Naval Battle of the (B. C. 241).

See PUNIC WAR, THE FIRST.

ÆGEAN, The.

"The Ægean, or White Sea, ... as distinguished from the

Euxine."

E. A. Freeman, Historical Geography of Europe,

page 413, and foot-note.

ÆGIALEA.--ÆGIALEANS.