VOLUME 1 NUMBER 4

1902

JUNE

An ILLUSTRATED MONTHLY JOURNAL for BOYS & GIRLS

The Penn Publishing Company Philadelphia

| FRONTISPIECE (Priscilla and the Hopolanthus) | Anna Whelan Betts | PAGE |

| Priscilla and the Hopolanthus | Sidney Marlow | 115 |

| JUNE (Selected from the Vision of Sir Launfal) | Lowell | 118 |

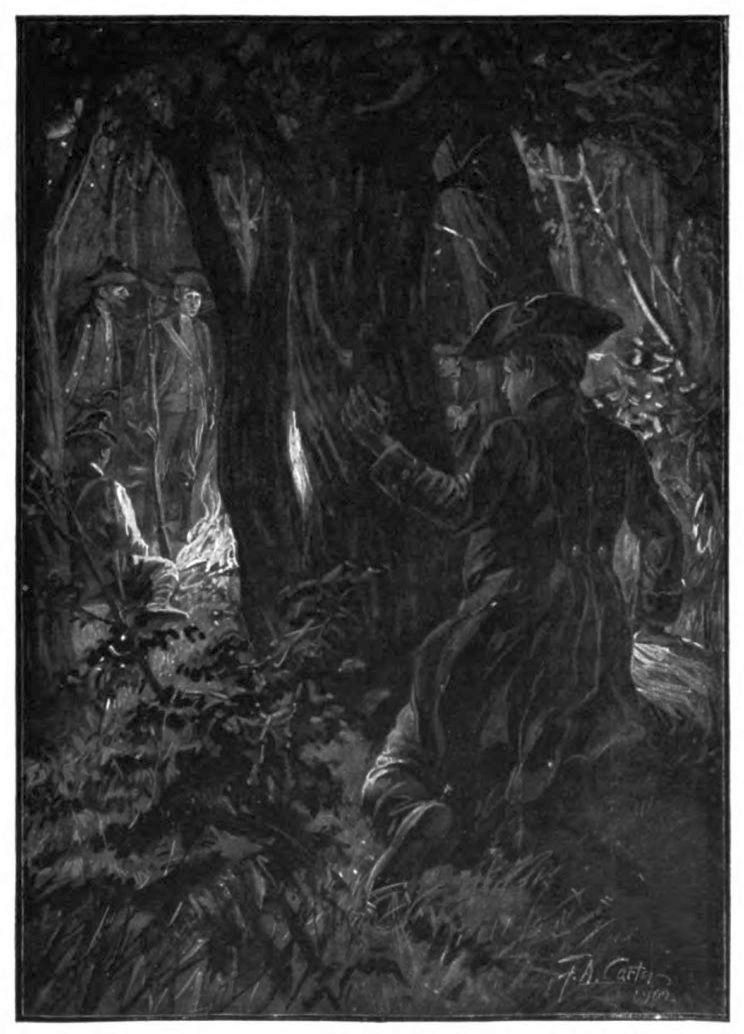

| WITH WASHINGTON AT VALLEY FORGE (Serial) | W. Bert Foster | 119 |

| Illustrated by F. A. Carter | ||

| A PROVIDENTIAL SPARK | William Murray Graydon | 128 |

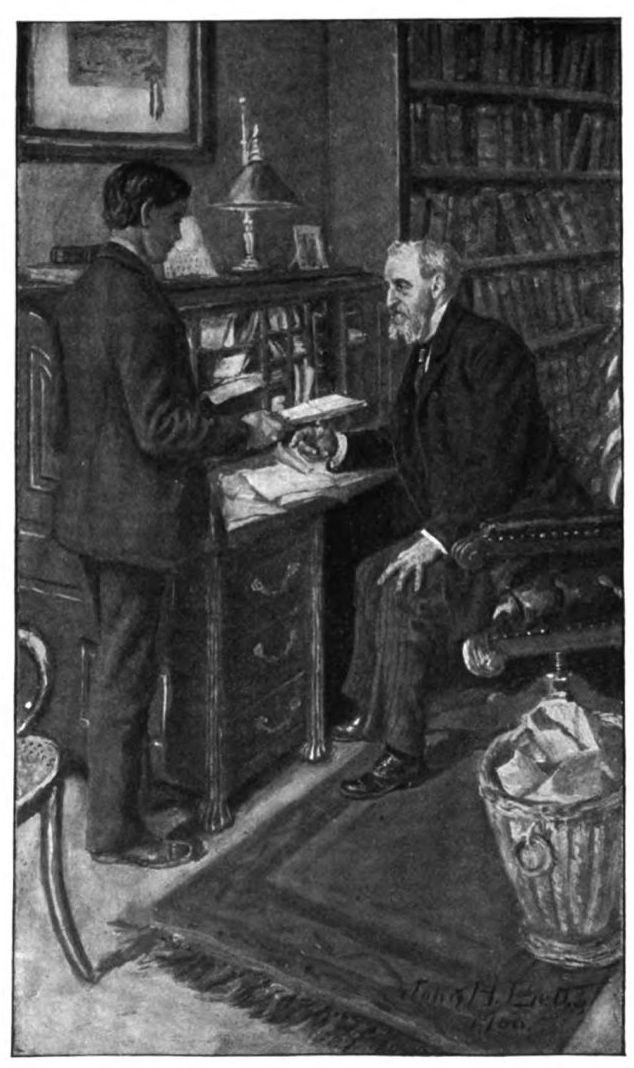

| A DAUGHTER OF THE FOREST (Serial) | Evelyn Raymond | 131 |

| Illustrated by J. H. Betts | ||

| SIX (Selected) | Minot J. Savage | 140 |

| WOOD-FOLK TALK | J. Allison Atwood | 141 |

| LITTLE POLLY PRENTISS (Serial) | Elizabeth Lincoln Gould | 143 |

| Illustrated by Ida Waugh | ||

| JUNE MEADOWS | Julia McNair Wright | 150 |

| Illustrated by Nina G. Barlow | ||

| WITH THE EDITOR | 152 | |

| EVENT AND COMMENT | 153 | |

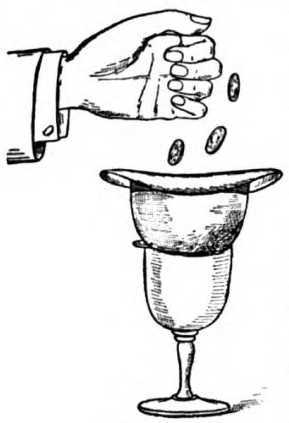

| IN-DOORS (Parlor Magic, Paper IV) | Ellis Stanyon | 154 |

| THE OLD TRUNK (Puzzles) | 155 | |

| WITH THE PUBLISHER | 156 |

An Illustrated Monthly Journal for Boys and Girls

SINGLE COPIES 10 CENTS ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION $1.00

Sent postpaid to any address. Subscriptions can begin at any time and must be paid in advance.

Remittances may be made in the way most convenient to the sender, and should be sent to

The Penn Publishing Company

923 ARCH STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA.

Copyright 1902 by The Penn Publishing Company.

VOL. I June 1902 No. 4

By Sidney Marlow

PRISCILLA just laughed quietly to herself and lay perfectly still. Then Susette called again, but now you could tell from the sound that she had taken Grace and Halbert and gone further into the woods. Probably she had decided that Priscilla had run on ahead and would be waiting for them at the shaky little bridge or the old red saw mill. What a scare Susette would have when she reached the old mill and Priscilla wasn’t there? And what business had Susette to make such an awful fuss just because a person chose to eat quite a good deal of cake, and a pickle, and a rather large plate of ice cream at the same meal? They wouldn’t hurt Susette, anyway.

Then once more the little girl heard her nurse calling her, and the voice came from such a long way off that somehow the sound made Priscilla feel just the least bit lonely. In about a minute and a half she would get up and follow the others. She would hide, though, and watch Susette clap her hands to her ears, and hear her give one of those jumpy little French screams when she came to the mill and there was no one there. No one could be quite so funny as Susette when she was really and truly frightened.

Priscilla was still smiling at the way the prim little nurse was sure to behave when she caught sight of something that made Susette, and the children, and the bridge, and the old mill, all fly out of her head just the way she had seen a flock of English sparrows dart out of the front lawn when Rover pounced down upon them from the terrace. It was only a big yellow and black bumble-bee, but who in this world ever saw a bumble-bee act like—well, the best way is just to go ahead and tell what it really did.

Almost the very first thing, and before Priscilla had time to even think whether she liked him or not, he put his little front foot up to his pert little countenance and wiggled his saucy little fingers at her, in a most objectionable manner. It was exactly for all the world like what the butcher’s boy did when Priscilla offered him a cream chocolate on the first day of April. At least, that’s the way it looked to Priscilla, but, between you and me, I rather suspect the bumble-bee was just wiping off the pollen that had stuck to his lips ever since dinner time. He hadn’t any napkin, you know, so what else could he do?

However, that wasn’t any excuse at all for what he did next. Remember, Priscilla had her eyes on him all the time, so there couldn’t be any mistake about it. The bumble-bee just simply reached up and raised his—yes, it was really—a dainty little three-cornered hat—just like the one in the picture of her great-great ancestor in the dining-room. Then he bowed, and he did it every bit as politely as Mr. Alwin, the minister, when he came up the front steps Sunday afternoon. Did you ever hear of anything like it? At first Priscilla thought she must have fallen asleep, so she sat bolt upright and rubbed her eyes. The moment she moved the bumble-bee again took off his hat, but for the life of her Priscilla couldn’t tell what he did with it. Once it seemed as if he must have slipped it under his left wing, but it’s quite as likely that he swallowed it. At any rate, there he sat with his head cocked to one side, and his little black bead of an eye twinkling impertinently, as if he had just asked, “Did you speak, ma’am?” It was very provoking.

Now, I wonder whether any little girl who reads this would have been wise enough to do what Priscilla did next? She saw now that at the very instant—really, at the beginning of the instant—she began to move, the bumble-bee would stop doing all these remarkable things. So she just lay quietly back in the deep, soft grass and half closed her eyes—or, perhaps, it was three-quarters—and must have looked exactly as though she were asleep. Then some things happened in that big oak tree which I’m sure never, never would have happened if the bumble-bee had known that, really, Priscilla was perfectly wide awake.

Indeed, his conduct was so very singular that Priscilla almost stopped being surprised. You couldn’t blame her, though, for giving a little start when she saw that he had changed his color from yellow to all black, and that, instead of buzzing about her, he was running along the limb of the tree on all his six legs, just exactly like—Why, really, he’d changed into a big black spider. To tell the truth, just at this point Priscilla was so astonished again that she couldn’t so much as move an eyelid.

The spider came running along the limb of the big oak until he was straight above Priscilla’s head. Then he stopped suddenly and began to fumble in some sort of a back pocket in his black velvet coat. The next moment a delicate silken thread came dangling down, down, down, and, before she fairly understood what was happening, Priscilla felt it tickling her very puggish little nose. Of course she was indignant, and raised her hand and brushed the ugly thing away. Only—the thread stuck to her fingers, and when she tried to wipe it off with her other hand, it stuck to that hand, too. And the miserable old spider, holding the thread lightly over one claw and pressing the other against the side of his puffy black stomach, was looking down and laughing fit to shake his eyes out.

But that was only the beginning. Priscilla was no coward, but you can guess how she felt when suddenly that old spider sat up straight and commenced to whirl his claws around each other like an electric fan, and the web commenced to roll up, and the girl began to be drawn right straight up into the tree. Even a grown person would have been astonished. And the spider kept on laughing.

In almost no time she was up in the tree, and truly she didn’t feel much bigger than the spider, and yet it didn’t seem to her that she’d lost much flesh since she left the ground. It was all very puzzling.

“That’s what I call bringing you up with a round turn,” said the spider, laughing immodestly—or immoderately, Priscilla wasn’t quite sure which of the words her mother used in such cases. His jacket was so tight that it seemed it must burst the very next giggle.

“Now, to business,” he remarked, suddenly, tucking his line away in his coat-tail pocket, and looking severely at Priscilla, as though it were she, and not himself, who had been behaving so foolishly.

“The Hopolanthus desires you to call and explain.”

“The—the who? I want to go right straight home.” interrupted Priscilla, with quite a good deal of shakiness in her voice.

The spider looked surprised, and for a moment he stood up perfectly erect—that is to say, as perfectly erect as is possible for a person with that kind of a stomach.

“Whenever a little girl lies down in the shade of the Hopolanthus Tree,” he went on, sternly, “it means that the Hopolanthus has business with her, and the only thing for me to do is to decide upon the route. I must ask you a question or two. Did you ever study botany?”

“Why—why, yes—some,” replied Priscilla, as soon as she had caught her breath.

“You have, eh! Well, then, how many cousins had your grandfather’s aunt? Be a little quick, please.”

“Why—but—you see—I guess I—I don’t know. Anyway,” she added, indignantly, as it dawned upon her that she was being imposed upon, “that hasn’t anything to do with botany. Not the least mite in the world.”

“Yes, it has. Yes, it has,” retorted the old spider, testily.

“It’s the very first thing you ought to know. It’s about your own family tree. I’m simply shocked.”

“You’re just dreadful,” exclaimed Priscilla, angrily, stamping her foot on the rough bark. “I shall not go a—”

“Oh, yes, I guess you will,” responded the spider, with a queer little twinkle in his eyes.

Then, before Priscilla could tell him that she really and truly wouldn’t move a step, she felt herself rapidly approaching the trunk of the tree. It seemed as if the old oak were suddenly drawing in the limb upon which she stood, just as a turtle draws in its long neck. She noticed, too, for the first time, a hole in the trunk—a very ordinary knot-hole, she would have said a moment before—which was growing bigger and bigger as she approached. Unless, perhaps, she, herself, was shrinking smaller and smaller. Suddenly, and exactly as if she did it on purpose—although she tried her best not to do it—Priscilla raised her two hands over her head and dived right through the knot-hole, just grazing the tip of her nose as she went in. Indeed, if her nose had been the least bit longer, or had stuck straight out from her face, like some people’s noses, instead of having its own neat upward curve, it would have been badly nipped. Of course, though, Priscilla had no time just then to think about noses. Down she went, and around she went, and very queerly, indeed, she felt.

Now, it isn’t quite easy to count the time while a person is falling, as I am sure any friend of yours who has dropped from the top of a church steeple will tell you if you ask him. To Priscilla it seemed as if she had been going just about as long as her little brother Halbert could sit still at the dinner table, when—puff, whist—and she had stopped.

“Now, come right along and don’t talk back. That’s one thing the Hopolanthus will not stand. You can say anything you choose if he hasn’t spoken first, but—”

“But suppose he speaks just as soon as I come into his parlor?”

“That’s impossible,” responded the spider, in a very positive tone. “He hasn’t any parlor; but come along.”

Everything was done in such a dreadful hurry that Priscilla felt as if she were not getting more than half as many breaths as she should.

“Please, Mr. Spider,” she protested, “you know I’ve come quite a—a quick distance, and I want to sit down and rest a few minutes.”

“Yes, of course,” replied the spider. But the instant Priscilla sat down she found herself moving along after her guide just as fast as before. It seemed to her that she was sliding out through one of the roots of the big oak tree.

“Here we are. Now be sure you don’t talk back.”

Slowly it seemed to grow light—not bright light, but just so that she could see where she was. She was in a room, and it looked a good deal more like a cellar than a parlor.

At one end of the room sat the Hopolanthus, and really until he spoke he wasn’t very terrible. He looked exactly like the kangaroo Priscilla once saw in the Zoo—only after you’d looked at him twice he was a good deal different.

“What has this—this young person been doing, now?”

The way he emphasized that word “now” made Priscilla forget all about not talking back. It was just as much as to say that of course she was always doing something wrong, and the only question was as to what she had done last. She opened her mouth to reply, when she was violently seized by the arms, and a shrill voice from just behind answered for her.

“Ah, she eat ze cake—ze big piece of cake, and ze big—ah, ze emense plate of ze ice cream. It is not wonder she lie here and keek ze grass, and make ze dreadful groan. Ze sillee child.”

And Susette shook her again, and Grace and Halbert danced around and yelled like a pair of young savages. It was a full minute before Priscilla could find her voice.

“You had no business to wake me up just when—you always do things wrong. I was just going to tell the old Hopolanthus that—”

But the children stopped dancing around, and Susette stood still and stared—which wasn’t common for Susette—and Priscilla couldn’t help seeing that they didn’t know what on earth she was talking about. She rubbed her eyes and looked up among the branches of the big oak. There was nothing there—neither bumble-bee, nor spider, nor Hopolanthus—only a small green tree toad who winked his dull little eyes just exactly as if he might, or might not, know all about it.

By W. Bert Foster

The story opens in the year of 1777, during one of the most critical periods of the Revolution. Hadley Morris, our hero, is in the employ of Jonas Benson, the host of the Three Oaks, a well-known inn on the road between Philadelphia and New York. Like most of his neighbors, Hadley is an ardent sympathizer with the patriot cause. When, therefore, a dispatch bearer is captured on the way to Philadelphia, he gives Hadley the all-important packet to be forwarded to General Washington. The boy immediately escapes with it, and, after many perilous experiences, finally makes his way across the river to the Pennsylvania side. On the road, Hadley, failing to give the countersign, is stopped by a foraging party of Americans; but by his honest bearing he wins the attention of John Cadwalader, a personal friend of Washington, just then journeying to the American headquarters. Under his protection, our hero speedily arrives at his destination, and delivers the dispatches. Hadley then returns to the Three Oaks to resume his duties. But the lad is destined for a more eventful life. Shortly afterwards he receives an urgent summons from Cadwalader, whereupon he immediately sets out for the patriot headquarters.

AS Lafe Holdness said, the enemy could take nothing from the boy courier on this journey—nothing of information or papers of value; but the possibility of being waylaid and beaten, perhaps killed, was not pleasant to contemplate. Hadley could scarcely understand the veiled warning he had received from Lillian Knowles. Was her father about to stop him on the road, believing that he again carried documents of importance to the American forces? He did not wish to fall into Colonel Creston Knowles’ hands just then, for the latter was angry enough with him as it was, and Hadley did not care to add to his irritation.

It might be, however, that somebody else had overheard a part of the recent conference in the inn stable, and Lillian was cognizant of the fact. Some Tory visitor, perhaps, had known of his starting forth. He drew rein again in the shadow of a long pile of cordwood which bordered the wall of the Benson estate, and felt in the darkness for a stout club, heavy enough to do a man’s head serious damage, but not too clumsy for him to swing easily. Then he chirruped to Black Molly, and she trotted on, her master keeping his eyes sharply open for trouble.

He was too proud to ride back and ask Lafe to come with him; Hadley did not lack personal courage. But he was nevertheless all of a tremor as the little mare trotted over the hard road. He gripped the club nervously, and tried to pierce the gloom, which was thickest, of course, under the trees which bordered the road. He was taking the shortest road to the ferry to-night, for there was no trouble to be apprehended there from British soldiers, and he would be sure to get quick transportation to the other side, for the people at the ferry were loyal. He would not have gone around by the Alwood house again for a good deal.

Rod after rod the inn was left behind and Black Molly had now brought him quite a quarter of a mile from the Benson place. There were no other houses on this road until he passed the Morris pastures, where he had his unpleasant meeting with Lon Alwood the day before. The mare footed it nicely over the road until now; but suddenly she threw up her head, her quivering ears pointed forward—Had could see them as dark as the night was—as though she listened to some sound too faint for her rider’s dull hearing to catch.

“What is it, Molly?” the youth demanded, holding a tight rein and gripping the club more firmly than before.

Instantly a harsh voice addressed him out of the darkness. “Stand there, and deliver!” At the same instant a figure sprang before the little mare and her bridle was seized by a firm hand. “Don’t make her dance!” ordered the stranger; “for if you do I’ll put a ball through her head and perhaps one through you.”

Hadley saw that the speaker waved a big horse-pistol in his other hand, and he spoke quietingly to Molly. “What do you want?” he demanded, in as brave a tone as he could assume.

“Give me what you carry,” commanded the other, still speaking gruffly. Hadley felt sure that it was a disguised voice, and remembering what Lillian Knowles had said to him as he left the inn, he wondered who the person was who had halted him. “No slippery tricks, Had Morris!” growled he at the horse’s head. “Hand me the papers you carry. Give me what you’ve got.”

But the strain of disguising his voice grew too much for the fellow, and as he talked he unconsciously dropped back into his usual manner of speaking. At once Hadley, although he was still unable to see his face, knew that it was Lon Alwood who had stopped him. And he was puzzled by the discovery, for he wondered how Mistress Lillian could have known of the Tory youth’s intention.

His mind did not work in one direction alone, however. Before Alwood had reiterated his demand Hadley was preparing to make answer. “You want what I carry?” he cried. “Then take it!” and swinging up the club suddenly he brought it down again upon the shoulder of his enemy. Lon roared and dropped both the pistol and the mare’s bridle rein; but Hadley did not come out of the affray without trouble.

Black Molly was startled by the blow and darted to the side of the road. Before the American youth could pull her in she was in the ditch, and only her quickness saved her from a disastrous fall. As she slid down the steep side of the gulley Had slipped his feet from the stirrups and leaped to the ground. Lon, with many imprecations and threats, groped madly about the dark roadway, and finally found the pistol. He was maddened beyond all control now, and dimly beholding Hadley’s bulk through the gloom—where he stood on the edge of the ditch urging the mare out upon the level again—he aimed the weapon and would have fired at his old schoolfellow point-blank!

But before his finger pressed the trigger a third actor appeared upon the scene. A man sprang from the bushes on the far side of the road and in two strides was beside the Tory. He seized Alwood’s arm, and the pistol ball flew wide of its intended mark.

At the moment the shot was fired Hadley had managed to half drag Black Molly from the ditch. His quick side glance saw the danger, and he sprang for the steed’s back; the explosion of the heavy pistol frightened Black Molly again, and before her rider was firmly settled in the saddle she was off like the wind. He obtained, however, another swift glance at the two figures struggling in the roadway behind him, just as the second barrel of the weapon was exploded. The flash lit up the scene, and with astonishment Hadley recognized the person who had saved him as Colonel Knowles’ cockney servant.

He and Molly were a good mile further on their way, however, before he had time to think much of this surprising fact, for the little mare ran like a scared rabbit. “Who could have sent the man to help me?” he thought, when Molly had finally settled into a respectable pace. “Surely not his master, and Mistress Lillian—”

To believe that the Colonel’s daughter had done him this favor—had sent William to assist him in overcoming the Tory youth—was rather pleasant; yet it seemed too improbable to be true, and he wondered much as he rode swiftly on to the ferry.

There was no trouble in crossing the river on this night. He found fires burning on the banks, and the ferrymen were wide awake. There was considerable bustle at the landing, and Hadley learned that several parties bound for Philadelphia had gone over ahead of him, and that others were expected. The loyal Jersey farmers and farmers’ sons were hastening to join General Washington, eager to take part in this new movement against the enemy. The boy was not delayed or molested in any way, and once on the Pennsylvania shore he urged the little mare to the utmost, passing party after party of recruits, all hastening in the same direction.

Not long past midnight he reached the farmer’s at which he had previously changed horses. The man remembered him, and, thanks to Hadley’s first appearance there under Colonel Cadwalader’s protection, the youth was enabled to get a fresh mount on this occasion. The farmer, too, was able to give him certain information about the movements of the American forces.

“You will not find his Excellency at Germantown,” the farmer declared. “Aye, an’ ye’ll not catch him at Philadelphia, I’m thinkin’. The Redcoats are coming up the Chesapeake, an’ the army’s movin’ south to shelter the city from attack.” Then followed directions relating to crossroads and bridle paths, by following which he might overtake the army on its way to Wilmington.

Without waiting for sleep, but fortified with a hearty meal which the farmer’s wife prepared, Hadley set off again within the hour on a fresh mount. He was weary, saddle-sore, and parched by the August heat. But he was obeying orders, and although he did not understand the importance of the verbal message Holdness had given him for Colonel Cadwalader, the youth knew what his duty was. He could not foresee what was to happen and what sights he should witness before he again rode into the yard of the Three Oaks Inn. The people whom he passed, the Tory element was not in evidence, were very cheerful regarding the battle which they believed would be fought as soon as Lord Howe’s troops landed. Despair and inaction had held the Colonials in a hard grip during these past few months; but now there was a chance to do something, and the farmers were again hopeful.

It so happened that while Hadley Morris was riding hard over the dusty roads to overtake Washington’s personal staff on this 24th day of August, the American army, augmented by fresh recruits, and some 11,000 strong, marched through the length of Front street. Philadelphia had seen some gloomy days of late, but the appearance of so many armed men was calculated to raise the spirits of the populace a little; yet it is said that the cheering along the line of march lacked that inspiring quality with which a conquering army usually goes to battle. It was known that they were about to meet an enemy well-trained and seasoned, and, in addition, outnumbering them by several thousands.

Philadelphia had from the beginning of the war been the headquarters of rebellion, and the British were determined to humble the city. How could Washington’s forces hope to cope with men who had fought on half the battle-fields of Europe? It had been a handful of untrained farmers, however, who had beaten back the grenadiers at Bunker Hill; and it could scarcely be called a trained army that had driven the Redcoats finally out of Boston town.

It was long past mid-afternoon when Hadley overtook the rear guard of the American army. It was no easy matter to find the commander and his staff, and, when found, to select Colonel Cadwalader from the other officers and get near enough to him to deliver the message he carried. But the instant the officer saw and recognized the youth he graciously called him near. Evidently Lafe Holdness’ message, which had been a mystery to Had because he did not understand what the seemingly simple sentence meant, was most important, for Colonel Cadwalader hurried off at once to General Washington, bidding the boy remain with the column until he returned.

When he did return there was with him the young officer who had desired Hadley as a recruit on the day he brought dispatches to the Commander-in-Chief at Germantown. “I cannot let you go back just yet, Master Morris,” Colonel Cadwalader declared; “I may have work for you to do later. Meanwhile I shall place you in Captain Prentice’s care,” and he indicated the smiling subordinate officer. “You are not obliged to fight if it be against your conscience; but you may see some fighting before you return to Jersey.”

He wheeled his horse and rode away again, and Captain Prentice offered the youth his hand. “Leave the nag, Morris,” he said, cordially, “and take your place with ‘Foot and Leggets’ company. Your horse seems about done for anyway, and you will be able to pick up a better one when you return. You’re to go with me, and I am in the infantry.”

And so, rather unexpectedly, Hadley found himself marching with the patriot forces toward Wilmington. Captain Prentice secured him a gun, and he shared the rations of the good-natured fellows about him. The youth was very tired after his long ride, but walking was better than riding, and there were times when the ranks rested. The next day, however, the army reached the Delaware town, only to learn through the scouts that the British had landed at the head of the Elk River, fifty miles or more from Philadelphia. The news spread, too, how greatly the Redcoats outnumbered the Americans. There were 18,000 of the former, and the faces of even the rank and file grew grave.

The Americans marched to Red Clay Creek, beyond Wilmington, and for several days there were smart skirmishes between portions of the two armies. But there was no decisive engagement, and finally Washington outgeneraled Howe and fell back upon the Brandywine, which he crossed at Chadd’s Ford, posting his army on the hills to the east. Meanwhile Captain Prentice’s command had seen little fighting, and both the young officer and Hadley Morris were anxious to get closer to the firing line than they had been thus far.

Hadley had forgotten his original expectation of returning at once to the Three Oaks Inn, after having delivered his message to Colonel Cadwalader; and it looked as though the Colonel had forgotten him. But he was so excited by the prospect of a battle that he was not chafing over the delay of his return journey. Without doubt a fight was imminent, the commanders of the opposing forces maneuvering for the best positions for their line of battle.

Thus August slipped away, September came, and the fateful eleventh day approached.

IN the excitement of those September days, when the two armies overran the Pennsylvania hills to the west and south of Philadelphia, Hadley came near forgetting his Uncle Ephraim and the promise he had made his mother regarding the old man. Miser Morris had so repelled his nephew’s kindly efforts to help him, that the boy felt he was no more able to do him any good while at the Three Oaks than he was miles away from the Morris farm in the lines of the Continental troops. And then, the glamour of the life—the drilling, the marching, the uncertainty, the danger—all fed his imagination and inspired him with actual delight. Prentice declared almost hourly that Hadley was “spoiling a good officer by hanging about a country inn.”

“I don’t feel that I could regularly enlist,” the boy said to him, “so I am not likely to be an officer yet awhile. I am here only as a volunteer, and my conscience troubles me, too, at that.”

But all things end in their own good time, and the long wait which ensued after the landing of the British finally was closed on the morning of September 11th. Captain Prentice’s command had not even tasted a skirmish until that day; but Hadley—nor the captain himself—could find no fault with the position they occupied during the fearful hours which followed the first gun of attack. Hadley was eager to see a real battle, to see the armies charge each other and try their strength upon a real battle-field, instead of individual men snapping their muskets at one another in little skirmishes. Before the end of that day he could not realize what awful motive had ever urged such foolish desire in his heart.

He saw men lying dead upon the browning hillsides; he heard wounded horses screaming in their death agony; the earth shook with the discharge of the heavy guns; the crackling of the musketry fire deafened him. The fife and drums, the uniformed officers, the marching soldiery made no appeal to Hadley Morris now. Wounds and death were all about him, and fear gripped his heart as though in a vice. Time and again as he heard the shriek of the bullets over his head he could have fainted, or run away in abject terror, had he dared! But the thought of being considered a coward frightened him even more, and he stayed.

Once, when there was a lull of heavy firing on both sides, a strange sound reached his ears. Captain Prentice’s command was somewhat above and to one side of the main line of battle, and this sound, growing louder and more ear-piercing as the strange silence continued, had such an eerie effect upon the listener that Hadley actually shook with a nervous chill, without knowing what caused it. The sound was little more than a murmur—yet a very insistent, penetrating murmur.

“What is it?” Hadley whispered to the man who stood next him in the broken line.

“The cries of the wounded,” was the stern reply, and the boy was glad when a renewal of the conflict drowned the awful sound.

No history fittingly tells the story of that day’s struggle—the high hopes with which the battle was begun by the Americans, the determined, dogged resistance they offered the British soldiery. Yet its salient points are familiar enough. We do not like, even now, to speak at length upon the defeats of our arms even in that unequal war. But without doubt, had not Sullivan blundered and lost to the American cause a good twelve hundred men, the Battle of the Brandywine would have been placed upon the list of American victories.

Hadley saw the patriot army driven back and as they retreated he observed many of the men weeping like women at the thought of flying before an enemy which they had practically held in check since early morning. Captain Prentice, who had been recklessly courageous during the engagement, was wounded, yet still kept on the firing line with his arm and shoulder swathed in bandages. As they broke into the final disorderly retreat, an aide galloped to the young captain and said a word to him.

“Morris!” exclaimed Prentice, “follow this man to Colonel Cadwalader. He wants you. All’s lost here, anyway; there’s nothing more to be done.”

Hadley threw down his musket and ran beside the aide’s stirrup along the dusty road for nearly a quarter of a mile before overtaking the group of officers of which Colonel Cadwalader was the centre. The Colonel sat on his horse firmly and, despite the creature’s dancing, was writing rapidly on the pommel of his saddle.

“Morris,” he said, scarcely glancing at the youth. “It is over for to-day. You are not kept here with Captain Prentice by any enlistment, I believe?”

“No, sir.”

“Then you can go back if you wish—you can go home. We shall retreat, and whether His Excellency secures another such chance to meet the enemy soon, we know not. It is an awful thing—an awful thing! But that is not why I called you. There is a fresh horse yonder being held for you. Here branches the road to Philadelphia. You will not be molested, for the British have not yet crossed it—though it’s not sure they’ll not throw a column out between us and the city.

“This letter goes to Holdness at the Indian Queen Hotel in Fourth street—anybody will direct you. Then, when it is delivered, you may follow your own wishes, Master Morris,” and the gentleman leaned down and dropped the unsealed note into the boy’s hand with a grave smile. “Leave the horse where you exchanged steeds before on the Germantown pike—you already have a horse there, have you not?”

“I left one there, sir.”

“Very well. Now, off with you! I shall see you anon—and hear more of you to your credit, I believe,” and with a wave of his hand Colonel Cadwalader dismissed him.

Together with the men beside whom he had fought Hadley was nigh heartbroken over the result of the battle. The retreat was almost a rout in some parts of the field. The boy sprang upon the horse held by an orderly, and at once dashed away through the broken lines and soon left the disorganized army behind. It was a bitter hour, and, young as he was, the youth felt it keenly. How would he be greeted in the city toward which he was carrying the news of the battle? He could imagine with what despair the result of the struggle would be received.

But he could not imagine all that had occurred in the capital during the hours of that fateful day. The days of anxiety and suspense which had followed the landing of the enemy culminated that morning when the distant booming of heavy guns announced the beginning of a general engagement in the southwest. At the first cannon shot many people left their houses and collected in the streets, and all day long their straining ears listened to the thunderous muttering of the guns. About six o’clock it died away, but the groups in the street still listened and waited. The sun set and supper-time came and went unnoticed by those still remaining in the Quaker City.

Naturally there were not any great number of male adults, excepting the old men, or those burdened by family or business cares which actually forbade their being in the ranks of the patriot army. Of course, there were a few Tories left, but they were not active, as had been Joseph Galloway and the Allens before they were banished from the town. There were no young men—only boys and children hanging on the skirts of the various groups about the State House, or listening to the remarks of the wise ones gathered before the doors of the houses of public entertainment.

The women, too, whispered on their doorsteps to each other, or craned their necks out of the darkened windows to look nervously along the street. The sound of the guns had brought that grim, horrible Thing called War so much nearer to them than it had ever seemed before.

About eight o’clock there was some little disturbance at one of the inns called the Old Coffee House, where the story gained credit that Washington had won a victory, and some few began to cheer. But there was no authority behind the story, and the enthusiasm died out, and by nine o’clock the suspense was actually painful.

At last, far out Chestnut street toward the distant Schuylkill, there rose the sound of rapid hoof-beats. As the approaching horseman tore down the street voices rose and hailed him as he passed, and soon the clamor grew to a roar, which roused the town for blocks around. The people ran together toward the State House, and saw a youth on a foam-flecked horse, covered with dust, and exhausted, riding hard along the rough way.

Once he drew rein for a moment to inquire the way again to the Indian Queen; but he refused to answer any questions until he had ridden around into Fourth street and stopped before the door of the old hostelry.

“Had Morris!” exclaimed a voice in the crowd which poured out of the place, and the lank figure of Lafe Holdness pushed through the throng and helped the boy from the saddle.

“What’s the news? Tell us of the battle!” cried the crowd. “What does the lad bring?”

Hadley thrust Colonel Cadwalader’s letter into the scout’s hand first. Then he said weakly to the anxious citizens: “There has been a battle fought to-day; but there are plenty of stragglers to tell you of it. There is another messenger in town already—he can tell you better than I.”

“But, is it defeat or victory?” somebody cried.

“The army has been beaten—I don’t know how badly. They say somebody blundered, and General Washington is obliged to fall back. The French Marquis was wounded, I was told—seriously. The army is marching northward and there will be plenty of stragglers here soon.”

Then he clutched Holdness by his sleeve. “Get me a bed, Lafe. I am nearly dead with riding so far on top of all that’s been done to-day. And I have no money.”

“Tut, tut!” exclaimed the Yankee. “Never mind money here, lad. Ye’ll be well entertained—I’ll speak to somebody about ye. But I must be off myself at once.”

And in ten minutes Hadley was alone in a little room at the top of the house, anxious to rest after his toilsome ride, while Holdness was away on some business connected with Colonel Cadwalader’s note. The city was, however, in a tumult. Hadley’s news had now been verified by a dozen other messengers of ill-tidings, and few in Philadelphia that night believed that Washington could successfully oppose the enemy again before Howe threw his troops upon the city itself.

Indeed, when Hadley appeared in the street the next morning to mount his horse brought around by the stableman, the same groups of excited citizens seemed to surround the Indian Queen which had been there the night before when he arrived. As far as he could learn, everybody seemed to believe that the city was doomed to capture by the British, and that the defeat of Brandywine could not be retrieved. A night’s sleep, however, had renewed Hadley’s courage as well as refreshed his body. When he clattered out of town, following the road northward toward Germantown, he drew in, with every breath of the fresh morning air, the feeling that all was not yet lost. He remembered how bravely his comrades had fought the day before; how reluctant they had been to fall back, even when commanded to do so. He thought of General Washington himself, and a mental picture of His Excellency’s stern, firmly lined face rose before him. That was not a man to give up—nor would General Knox, nor Wayne, nor Colonel Cadwalader, nor even young Captain Prentice! Before he reached the farm-house where he had left his horse, he was confident that Philadelphia would not be given over to the enemy without a second struggle.

And with that belief another idea entered the boy’s mind. He had experienced a real battle. It had frightened him, and the thoughts of some of the awful things he had seen and heard still troubled him; but he felt that now, when he had been initiated in war’s alarms, it was too bad that he should not remain and fight again when the patriots tried to keep the enemy out of the city.

“I’ll go home as quick as ever I can and beg uncle to let me go—he must let me enlist!” the boy thought. “Anyway, if he says ‘no,’ I’ll go just as I did this time, find a gun, and stay as long as the battle’s on. I know Jonas won’t care.”

He came again to the Ferry and crossed it at night, Black Molly, he had found her in good condition at the farmer’s, apparently as eager to be home as himself. The news of the disastrous battle had preceded him, and everywhere Hadley was met by anxious inquiries. He met no Tories, for most of them had gone to join the British forces; but the American farmers had again lost hope.

As he was poled across the river one of the ferrymen said to him: “Morris, ye’d best watch sharply as ye go along home. It is reported a party of Tories crossed below here not two hours ago. They used old Alwood’s bateau, and Brace Alwood is with them. They’re meaning no good to folks, I take it.”

“I thought all the Tories would be with the King’s men,” said the boy. “I heard on the road that they’ve sworn to march into Philadelphia with the Redcoats when the city is captured.”

“Well, Brace has got business of some kind over here—and it isn’t any good business, I’ll be bound. You’d better warn Jonas. They may come to the inn.”

Hadley was somewhat troubled by this information. Brace Alwood had been a reckless sort of a young man before the war broke out, and had incurred the enmity of many of the neighbors. It was reported that since he had joined the British he had given full sway to his more harmful propensities, and that he was noted among the Tory hangers-on of the King’s troops for his cruelty and bitter enmity against the patriots. He had obtained some petty office in the army, and now, with others, perhaps as brutal as himself, had come into his own neighborhood for no good purpose. Surely, if he had crossed the river merely to visit his father and mother, he would not have brought a troop with him.

But Hadley saw nobody on the road until he came abreast of his uncle’s property. Then he did not see any man, but a light in a clump of trees some distance back from the horse-path, and in Miser Morris’ pasture, attracted his attention. This was so strange a place for a fire, for a fire it was Hadley could tell by the intermittent leaping and fading of the light, that he could not go by without investigating, and after riding Black Molly a few rods beyond the grove in question, he dismounted, tied her to a fence rail, and crept over to reconnoitre.

There was a campfire in the middle of the clump of trees. It was well hidden from the house and outbuildings, and scarcely discernible from the highway. But when he got into the edge of the grove Hadley saw with surprise that although the fire was small there was a good-sized company about the blaze. He counted eight heavily armed and roughly dressed men lying about the fire, but Brace Alwood, Lon’s older brother, was not among them.

“Now, why should these fellows be roosting here?” thought the American youth, quite puzzled. “Of course they know that most of our men are away now with the army, and have they really come over here to harass the unprotected homesteads? If they have, and if they trouble the farmers’ wives, it will be too hot about here for the Alwoods to stay when the men do come back.”

A crackling in the bushes startled him, and he crouched lower. The Tories seemed so sure of their position that they did not keep a guard, and now two other figures came rapidly into the circle of the firelight, Hadley noticing that their approach was from the direction of his uncle’s house. An instant later he recognized Brace Alwood, the probable leader of this party of bushwhackers. He was grown much older looking since he had left home, and his bronzed face was covered by a tangled growth of beard. His companion he held by the arm, and Hadley saw that it was Alonzo.

“Here he is, boys,” declared Brace, with a laugh. “He’s young, but he’s sharp—a reg’lar fox for cunning. I found him watching the premises yonder, and he tells me everybody’s gone for the night, and the old man is in the house. All we got to do is to wait an hour or so till things get thoroughly quieted down, and then make our call. Miser Morris’ll be glad to see us, eh?” and the fellow laughed unpleasantly.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

By WILLIAM MURRAY GRAYDON

IF there is any one incident in my past life that I particularly dislike to dwell upon, it is the night I spent in a lonely mountain cabin in Northwestern Arizona.

I had left the little mining settlement of San Rosa early that morning to visit a ranch belonging to a friend of mine that lay some ten or twelve miles to the westward.

I had never been there before, but from the directions given me, I felt sure I could find the place without difficulty.

I had to cross two or three mountain spurs, and pass through a couple of deep ravines to reach the high stretch of table land where the ranch was located.

I am fond of sport, and to this must be attributed the adventure which placed me in such peril. At sunrise I was four or five miles on my way, and while riding through a deep wooded hollow, I discovered bear tracks in a bit of soft ground, which had the appearance of being fresh.

Here was a temptation too great to be resisted, and, hoping to obtain a shot at Bruin, I followed the trail up the side of the ridge. The footprints which were too small to be those of a grizzly, soon vanished, of course, but I rode on over the hilltop and down into the ravine beyond, eager to get a glimpse of the animal.

But Bruin failed to make his appearance, though I followed the hollow for several miles, and finally concluded to give up the search and strike for my destination.

But here I was confronted by a puzzling problem.

I had passed several intersecting ravines on my way, and now I was utterly at a loss which one to take.

I made a speedy choice, however, for there was no time to lose in hesitation, and rode briskly on for two or three hours.

But none of the landmarks which I had been warned to look for appeared, and I had to admit that I was lost.

It was now about four o’clock in the afternoon, and the setting sun showed that I had been traveling in the proper direction—in the general sense of the word, but whether the ranch was close at hand or not, I had not the remotest idea.

Some distance ahead I could detect the sound of running water, so I concluded to slake my thirst, and then strike for the highest point of ground to be found where I could obtain a view of the country.

In a moment I saw the water sparkling at the bottom of the ravine, and, as I rode down to the spot, a startling and unpleasant sight met my eyes.

Two men, an evil-faced Mexican and an Apache Indian, were sitting by the side of a great rock. Their horses were tied to saplings a few feet away, and their arms, I noted with relief, were lying on the ground, almost equally distant.

The surprise was mutual, for the mossy path had muffled the sound of my horse’s hoofs.

I recognized both instantly. The Mexican was Luiz Castro, a man who bore a bad name among the settlements, and his companion was Scarface—so called from a couple of ugly knife marks on his cheek—and a very bad Indian, indeed, if reports were to be believed.

The Apache had been driven from his tribe for some misdemeanor, and for several years he and the Mexican had been inseparable companions—a very odd friendship, to say the least.

I concluded not to stop for a drink at that spring.

“Can you tell me the way to Block’s Ranch?” I inquired, respectfully.

The Apache looked at me stolidly, but Castro quickly replied:

“Si, señor; straight ahead through yonder ravine. You can’t miss it.”

I thanked him, and nodding briefly, rode on. The ravine referred to was just ahead, and I had gone a mile or more when the suspicion suddenly occurred to me that Castro might have misdirected me for some evil purpose.

I carried quite a sum of money which I had no desire to lose, and as rapidly as possible I rode on until a sudden gloom warned me that darkness was at hand. The ravine showed no signs of terminating, and my suspicion became a certainty.

The two scoundrels had guided me to this lonely spot with the intention, no doubt, of waylaying and shooting me. They were quite capable of such a deed, I well knew.

I shivered at the thought, and taking a hasty glance behind, put spurs to my mustang and trotted ahead as rapidly as the narrow, uncertain path would allow.

In five minutes the ravine widened and I saw a small clearing just ahead, in the centre of which was a rude log cabin. I rode eagerly to the door and was disappointed to find it empty. Some lonely miner, perhaps, had once lived there until he either met a violent death or abandoned the place in search of a better claim.

It was now quite dusk, and I realized the hopelessness of proceeding farther that night.

The ravine narrowed again just ahead, and the steep ridges on each side forbade any attempt at climbing.

My mind was made up in an instant. Here I must spend the night.

I hastily picketed my horse outside where he could find plenty of grass, and entered the cabin. I was agreeably surprised to find it in such good condition. The door was firm on its hinges, and sockets on each side seemed to invite the heavy bar that was lying close by on the floor. The window shutter could be secured in the same way.

I lost no time in securing the door and window, and then I felt comparatively safe, for I was well armed with a Winchester and a pair of revolvers.

I had crackers and jerked beef in my knapsack, and, making a cheerful blaze in the fireplace, I ate a hearty lunch. Then I lit my pipe and sat down with my back against the wall where the heat could easily reach me.

I could hear my horse moving about outside, but no other sound reached me; and I began to be ashamed of my fears. I smoked and pondered for two or three hours, and I was just considering the advisability of bringing my horse inside the cabin for better security, when, without the least warning, a sharp report rang in my ears, and a bullet buried itself in the log within an inch of my face.

Startled as I was, I had sufficient presence of mind to throw myself flat on the floor, grasping my rifle in the fall.

I did not intend this for a ruse, but my unknown enemy evidently thought I had fallen from the effects of his bullet, for instantly I heard a thumping on the door, and a few words spoken in a low voice. Castro and the Apache were outside, I had no doubt.

The shot was fired through a chink in the logs, and, creeping over the floor, I put my Winchester to the orifice and let fire twice in succession, to let them know that I was not a dead man yet, and determined not to be one if I could help it.

A hasty glance at the cabin walls showed me that wide cracks abounded everywhere, and, alarmed at the peril I was in, I tore off my coat, and, running swiftly to the fireplace, smothered the blaze and stamped out the embers.

I breathed easier when this was done, for, of course, my foes could not do any accurate shooting in the dark. Then I sat down in the centre of the floor to await the next move. It was a trying situation, and the thought of spending the long hours of the night in baffling the attempts of two would-be assassins was terrifying.

For a long time all was quiet, and then I heard them fumbling at the door and the window. This gave me little concern. I knew they could not force an entrance there.

Then another hour went by, and I was beginning to hope the miscreants had abandoned their scheme, when I suddenly became aware that some one was on the roof. I understood instantly what this meant. My foes intended to come down the chimney.

The sounds were so loud and so close that I believed one of them to be already descending, and snatching an armful of straw from the pallet, I dashed it on the fireplace and applied a match.

A few seconds later I realized what a dangerous trap I had blundered into, for as the blaze flooded the room with light, a rifle cracked, and I was knocked forcibly to the floor.

I believed for a moment that I was mortally wounded, but a little later I found that the bullet had struck my watch and glanced harmlessly off, after shattering the works.

I was not slow to comprehend the trick that had been played on me, and without any delay I crept to one corner of the room, which by this time was comparatively dark, for the straw had nearly burnt itself out. One of the fellows had remained below, ready to shoot, while his confederate worked the cunningly laid scheme from the roof.

For a time I was pretty sore from the shock, and then I began to fear that as a last resource they would come down the chimney in earnest.

I concluded to be on the safe side by preparing for such an emergency, and as the fire was now out, I gathered up what straw remained and piled it in the chimney place, ready to use if occasion required, though I determined to make sure that my enemy was actually on his way down before I flooded the cabin with light again.

I suppose two hours must have passed this time without the slightest move from the miscreants, but I remained watchful and alert, with my Winchester on my knee.

Then I was startled to see a tiny flame licking the base of the straw pile. Some sparks must have lingered in the embers of the previous fire, and I rose quickly to put out the blaze.

But before I could reach the spot the tiny flame had expanded with startling celerity, and the fireplace was a glowing furnace.

I looked hurriedly around for shelter, but, before I could move, a hoarse cry rang out from the chimney, and down tumbled Scarface, the Apache, into the seething fire.

I dashed forward and dragged him out on the floor by one leg, before the flames could do him serious injury. He was stunned from the fall, though, and before he was able to offer any resistance, I had him securely bound, hand and foot, with a strong rope that I fortunately chanced to have in my pocket.

During this time Castro was probably on the roof, for no shots were fired through the logs; and, as the straw burned itself out, I felt that the siege had ended in my favor.

From Scarface I had nothing to fear, and I knew that the cowardly Mexican would not attempt to carry out a plan at which his comrade had failed so disastrously.

The Indian spent the remainder of the night in groaning, and when the welcome daylight shone through the logs my friend, Block, arrived on the scene with several of his ranchmen, and my siege was over.

The ranch turned out to be only two miles away. My friend had been expecting me on the previous day, and the sound of shooting during the night led him to make a search in this direction.

Castro had decamped, taking my horse with him, but he was captured at a neighboring settlement a week later.

Scarface recovered from his burns and was handed over to the sheriff, who put him where he was not likely to injure any person for some time to come.

My escape that night was truly a providential one. The crafty Apache had been stealing without a sound down the broad chimney, when the little spark that was smouldering for hours burst into a blaze at just the right moment, for if Scarface had gained the interior of the cabin this story would probably have never been written.

By EVELYN RAYMOND

Brought up in the forests of northern Maine, and seeing few persons excepting her uncle and Angelique, the Indian housekeeper, Margot Romeyn knows little of life beyond the deep hemlocks. Naturally observant, she is encouraged in her out-of-door studies by her uncle, at one time a college professor. Through her woodland instincts, she and her uncle are enabled to save the life of Adrian Wadislaw, a youth who, lost and almost overcome with hunger, has been wandering in the neighboring forest. To Margot the new friend is a welcome addition to her small circle of acquaintances, and after his rapid recovery she takes great delight in showing him the many wonders of the forest about her home. Many weeks later, in one of their conversations, a remark from Adrian causes Margot to question her uncle as to her father’s whereabouts. It is just this knowledge that her guardian, knowing it to be best, has so carefully kept from her. Fearing that Adrian’s presence might, in some way, increase the girl’s interest in her father, he puts the matter before the young man. It is then decided that it were better for Adrian to take his departure.

BUT Adrian need not have dreaded the interview to which his host had summoned him. Mr. Dutton’s face was a little graver than usual, but his manner was even more kind. He was a man to whom justice seemed the highest good, who had himself suffered most bitterly from injustice. He was forcing himself to be perfectly fair with the lad, and it was even with a smile that he motioned toward a chair opposite himself. The chair stood in the direct light of the lamp, but Adrian did not notice that.

“Do not fear me, Adrian, though for a moment I forgot myself. For you, personally—personally—I have only great good will. But—will you answer my questions, believing that it a painful necessity which compels them?”

“Certainly.”

“One word more. Beyond the fact, which you confided to Margot, that you were a runaway, I know no details of your past life. I have wished not to know and have refrained from any inquiries. I must now break that silence. What—is your father’s name?”

As he spoke the man’s hands gripped the arms of his chair more tightly, like one prepared for an unpleasant answer.

“Malachi Wadislaw.”

The questioner waited a moment, during which he seemed to be thinking profoundly. Then he rallied his own judgment. It was an uncommon name, but there might be two men bearing it. That was not impossible.

“Where does he live?”

“Number —, Madison Avenue, New York.”

A longer silence than before, broken by a long drawn “A-ah!” There might, indeed, be two men of one name, but not two residing at that once familiar locality.

“Adrian, when you asked my niece that question about her father, did you—had you—tell me what was in your mind.”

The lad’s face showed nothing but frank astonishment.

“Why, nothing, sir, beyond an idle curiosity. And I’m no end sorry for my thoughtlessness. I’ve seen how tenderly you both watch her mother’s grave, and I wondered where her father’s was. That was all. I had no business to have done it—”

“It was natural. It was nothing wrong, in itself. But—unfortunately, it suggested to Margot what I have studiously kept from her. For reasons which I think best to keep to myself, it is impossible to run the risk of other questions which may arouse other speculations in her mind. I have been truly glad that she could for a time, at least, have the companionship of one nearer her own age than Angelique or myself, but now—”

He paused significantly, and Adrian hastened to complete the unfinished sentence.

“Now it is time for her to return to her ordinary way of life. I understand you, of course. And I am going away at once. Indeed, I did start, not meaning to come back, but—I will—how can I do so sir? If I could swim—”

Mr. Dutton’s drawn face softened into something like a smile; and again, most gently, he motioned the excited boy to resume his seat. As he did so, he opened a drawer of the table and produced a purse that seemed to be well filled.

“Wait. There is no such haste, nor are you in such dire need as you seem to think. You have worked well and faithfully, and relieved me of much hard labor that I have not, somehow, felt just equal to. I have kept an account for you, and, if you will be good enough to see if it is right, I will hand you the amount due you.”

He pushed a paper toward Adrian, who would not, at first, touch it.

“You owe me nothing, sir, nor can I take anything. I thank you for your hospitality, and some time”—he stopped, choked, and made a telling gesture. It said plainly enough that his pride was just then deeply humiliated, but that he would have his revenge at some future day.

“Sit down, lad. I do not wonder at your feeling, nor would you at mine if you knew all. Under other circumstances we should have been the best of friends. It is impossible for me to be more explicit, and it hurts my pride as much to bid you go as yours to be sent. Some time—but, no matter. What we have in hand is to arrange for your departure as speedily and comfortably as possible. I would suggest”—but his words had the force of a command—“that Pierre convey you to the nearest town from which, by stage or railway, you can reach any further place you choose. If I were to offer advice, it would be to go home. Make your peace there; and then, if you desire a life in the woods, seek such with the consent and approval of those to whom your duty is due.”

Adrian said nothing at first; then remarked:

“Pierre need not go so far. Across the lake to the mainland is enough. I can travel on foot afterward, and I know more about the forest now than when I lost myself, and you, or Margot, found me. I owe my life to you. I am sorry I have given you pain. Sorry for many things.”

“There are few who have not something to regret; for anything that has happened here no apology is necessary. As for saving life, that was by God’s will. Now—to business. You will see that I have reckoned your wages the same as Pierre’s—thirty dollars a month and ‘found,’ as the farmers say, though it has been much more difficult to find him than you. You have been here nearly three months, and eighty dollars is yours.”

“Eighty dollars! Whew! I mean, impossible. In the first place, I haven’t earned it; in the second, I couldn’t take it from—from you—if I had. How could a man take money from one who had saved his life?”

“Easily, I hope, if he has common sense. You exaggerate the service we were able to do you, which we would have rendered to anybody. Your earnings will start you straight again. Take them, and oblige me by making no further objections.”

Despite his protests, which were honest, Adrian could not but be delighted at the thought of possessing so goodly a sum. It was the first money he had ever earned, therefore better than any other ever could be, and as he put it, in his own thoughts, “it changed him from a beggar to a prince.” Yet he made a final protest, asking:

“Have I really, really, and justly earned all this? Do you surely mean it?”

“I am not in the habit of saying anything I do not mean. It is getting late, and if you are to go to-night, it would be better to start soon,” answered Mr. Dutton, with a frown.

“Beg pardon. But I’m always saying what I should not, or putting the right things backward. There are some affairs ‘not mentioned in the bond’: my artist’s outfit, these clothes, boots, and other matters. I want to pay the cost of them. Indeed, I must. You must allow me, as you would any other man.”

The woodlander hesitated a moment as if he were considering. He would have preferred no return for anything, but again that effort to be wholly just influenced him.

“For the clothing, if you so desire, certainly. Here, in this account book, is a price list of all such articles as I buy. We will deduct that much. But I hope, in consideration of the pleasure that your talent has given me, that you will accept the painting stuff I so gladly provided. If you choose, also, you may leave a small gift for Angelique. Come. Pride is commendable, but not always.”

“Very well. Thank you, then, for your gift. Now, the price list.”

It had been a gratification to Mr. Dutton that Adrian had never worn the suits of clothing which he had laid out ready for use on that morning after his arrival at the island. The lad had preferred the rougher costume suited to the woods, and still wore it.

In a few moments the small business transactions were settled, and Adrian rose.

“I would like to bid Margot good-by. But, I suppose, she has gone to bed.”

“Yes. I will give her your message. There is always a pain in parting, and you two have been much together. I would spare her as much as I can. Angelique has packed a basket of food and Pierre is on the beach with his canoe. He may go as far with you as you desire, and you must pay him nothing for his service. He is already paid, though his greed might make him despoil you, if he could. Good-by. I wish you well.”

Mr. Dutton had also risen, and as he moved forward into the lamplight, Adrian noticed how much altered for the worse was his physical bearing. The man seemed to have aged many years, and his fine head was now snow-white. He half extended his hand, in response to the lad’s proffered clasp, then dropped it to his side. He hoped that the departing guest had not observed this inhospitable movement—but he had. Possibly, it helped him over an awkward moment, by touching his pride afresh.

“Good-by, sir, and again—thank you. For the present, that is all I can do. Yet I have heard it was not so big a world, after all, and my chance may come. I’ll get my traps from my room, if you please, and one or two little drawings as souvenirs. I’ll not be long.”

Fifteen minutes later Pierre was paddling vigorously toward the further side of the lake and Adrian was straining his eyes for the last glimpse of the beautiful island which, even now, in his banishment from it, seemed his real and beloved home. It became a vague and shadowy outline, as silent as the stars that brooded over it; and again he marveled what the mystery might be which enshrouded it, and why he should be connected with it.

“Now that I am no longer its guest, there is no dishonor in my finding out; and find out—I will!”

“Hey?” asked Pierre, so suddenly that Adrian jumped and nearly upset the boat. “Oh! I thought you said somethin’. Say, ain’t this a go? What you done that make the master shut the door on you? I never knew him do it before. Hey?”

“Nothing. Keep quiet. I don’t feel like talking.”

“Pr-r-r-rp! Look a here, young fello’. Me and you’s alone on this dead water, and I can swim—you can’t. I’ve got all I expect to get out of the trip, and I’ve no notion o’ makin’ it. Not ’less things go to my thinkin’. Now, I’ll rest a spell. You paddle!”

With that he began to rock the frail craft violently, and Adrian’s attention was recalled to the necessity of saving his own life.

AS the sun rose, Margot came out of her own room, fresh from her plunge that had washed all drowsiness away, as the good sleep had also banished all perplexities. Happy at all times, she was most so at morning, when, to her nature-loving eyes, the world seemed to have been made anew and doubly beautiful. The gay little melodies she had picked up from Pierre, or Angelique—who had been a sweet singer in her day—and now again from Adrian, were always on her lips at such an hour, and were dear beyond expression to her uncle’s ears.

But this morning she seemed to be singing them to the empty air. There was nobody in the living room, nor in the “study-library,” as the housekeeper called the room of books, nor even in the kitchen. That was the oddest of all! For there, at least, should Angelique have been, frying, or stewing, or broiling, as the case might be. Yet the coffee stood simmering at one corner of the hearth and a bowl of eggs waited ready for the omelet which Angelique could make to perfection.

“Why, how still it is! As if everybody had gone away and left the island alone.”

She ran to the door and called, “Adrian!”

No answer.

“Pierre! Angelique! Where is everybody?”

Then she saw Angelique coming down the slope and ran to meet her. With one hand the woman carried a brimming pail of milk and with the other dragged by his collar the reluctant form of Reynard, who appeared as guilty and subdued as if he had been born a slave, not free. To make matters more difficult, Meroude was surreptitiously helping herself to a breakfast from the pail and thereby ruining its contents for other uses.

“Oh! the plague of a life with such beasts! And him the worst o’ they all. The ver’ next time my Pierre goes cross-lake, that fox goes or I do! There’s no room on the island for the two of us. No. Indeed, no. The harm comes of takin’ in folks and beasties and friendin’ them ’at don’t deserve it. What now, think you?”

Margot had run the faster, as soon as she descried poor Reynard’s abject state, and had taken him under her own protection, which immediately restored him to his natural pride and noble bearing.

“I think nothing evil of my pet, believe that! See the beauty now! That’s the difference between harsh words and loving ones. If you’d only treat the ‘beasties’ as well as you do me, Angelique, dear, you’d have less cause for scolding. What I think now is—speckled rooster. Right?”

“Aye. Dead as dead; and the feathers still stickin’ in the villain’s jaws. What’s the life of such brutes to that o’ good fowls? Pst! Meroude! Scat! Well, if it’s milk you will, milk you shall!” and, turning angrily about, Snowfoot’s mistress dashed the entire contents of her pail over the annoying cat.

Margot laughed till the tears came. “Why, Angelique! only the other day, in that quaint old ‘Book of Beauty’ uncle has, I read how a Queen of Naples, and some noted Parisian beauties used baths of milk for their complexions; but poor Meroude’s a hopeless case, I fear.”

Angelique’s countenance took on a grim expression. “Mistress Meroude’s got a day’s job to clean herself, the greedy. It’s not her nose’ll go in the pail another mornin’. No, no, indeed.”

“And it was so full. Yet that’s the same Snowfoot who was to give us no more, because of the broken glass. Angelique, where’s uncle?”

“How should I tell? Am I set to spy the master’s ins and outs?”

“Funny, Angelique! You’re not set to do it, but you can usually tell them. And where’s Adrian? I’ve called and called, but nobody answers. I can’t guess where they all are. Even Pierre is out of sight, and he’s mostly to be found at the kitchen door when meal time comes.”

“There, there, child. You can ask more questions than old Angelique can answer. But the breakfast. That’s a good thought. So be. Whisk in and mix the batter cakes for the master’s eatin’. ’Tis he, foolish man, finds they have better savor from Margot’s fingers than mine. Simple one, with all his wisdom.”

“It’s love gives them savor, sweet Angelique, and the desire to see me a proper housewife. I wonder why he cares about that, since you are here to do such things.”

“Ah! The ‘I wonders!’ and the ‘Is its?’ of a maid! They set the head awhirl. The batter cakes, my child. I see the master comin’ down the hill this minute.”

Margot paused long enough to caress Tom, the eagle, who met her on the path, then sped indoors, leaving Reynard to his own devices and Angelique’s not too tender mercies. But she put all her energy into the task assigned her and proudly placed a plate of her uncle’s favorite dainty before him when he took his seat at the table. Till then she had not noticed its altered arrangement, and even her guardian’s coveted “Well done, little housekeeper!” could not banish the sudden fear that assailed her.

“Why, what does it mean? Where is Adrian? Where is Pierre? Why are only dishes for three?”

“Pst! ma p’tite! Hast been askin’ questions in the sleep. Sure, you have ever since your eyes flew open. Say your grace and eat your meat, and let the master rest.”

“Yes, darling, Angelique is wise. Eat your breakfast as usual, and afterward I will tell you all—that you should know.”

“But I cannot eat. It chokes me. It seems so awfully still and strange and empty. As I should think it might be were somebody dead.”

Angelique’s scant patience was exhausted. Not only was her loyal heart tried by her master’s troubles, but she had had added labor to accomplish. During all that summer two strong and, at least one, willing lad had been at hand to do the various chores pertaining to all country homes, however isolated. That morning she had brought in her own supply of firewood, filled her buckets from the spring, attended the poultry, fed the oxen, milked Snowfoot, wrestled over the iniquity of Reynard, and grieved at the untimely death of the speckled rooster. “When he would have made such a lovely fricassee. Yes, indeed, ’twas a sinful waste!”

Though none of these tasks were new or arduous to her, she had not performed them during the past weeks, save and except the care of her cow. That she had never entrusted to anybody, not even the master; and it was to spare him that she had done some of the things he meant to attend to later. Now she had reached her limit.

“Angelique wants her breakfast, child. She has been long astir. After that the deluge!” quoted Mr. Dutton, with an attempt at lightness which did not agree with his real depression.

Margot made heroic efforts to act as usual, but they ended in failure, and as soon as might be her guardian pushed back his chair, and she promptly did the same.

“Now, I can ask as many questions as I please, can’t I? First, where are they?”

“They have gone across the lake, southward, I suppose. Toward whatever place or town Adrian selects. He will not come back, but Pierre will do so, after he has guided the other to some safe point beyond the woods. How soon I do not know, of course.”

“Gone! Without bidding me good-by? Gone to stay? Oh, uncle, how could he? I know you didn’t like him, but I did. He was—”

Margot dropped her face in her hands and sobbed bitterly. Then ashamed of her unaccustomed tears, she ran out of the house and as far from it as she could. But even the blue herons could give her no amusement, though they stalked gravely up the river bank and posed beside her, where she lay prone and disconsolate in Harmony Hollow. Her squirrels saw and wondered, for she had no returning chatter for them, even when they chased one another over her prostrate person and playfully pulled at her long hair.

“He was the only friend I ever had that was not old and wise in sorrow. It was true he seemed to bring a shadow with him, and while he was here I sometimes wished he would go, or had never come; yet now that he has—oh, it’s so awfully, awfully lonesome. Nobody to talk with about my dreams and fancies, nobody to talk nonsense, nobody to teach me any more songs—nobody but just old folks and animals. And he went—he went without a word or a single good-by!”

It was, indeed, Margot’s first grief; and the fact that her late comrade could leave her so coolly, without even mentioning his plan, hurt her very deeply. But, after awhile, resentment at Adrian’s seeming neglect almost banished her loneliness; and, sitting up, she stared at Xanthippé, poised on one leg before her, apparently asleep but really waiting for anything which might turn up in the shape of dainties.

“Oh, you sweet vixen! but you needn’t ‘pose.’ There’s no artist here now to sketch you, and I don’t care, not very much, if there isn’t. After all my trying to do him good, praising and blaming and petting, if he was impolite enough to go as he did—Well, no matter!”

While this indignation lasted she felt better, but as soon as she came once more in sight of the clearing and of her uncle finishing one of Adrian’s uncompleted tasks, her loneliness returned with double force. It had almost the effect of bodily illness, and she had no experience to guide her. With a fresh burst of tears she caught her guardian’s hand and hid her face on his shoulder.

“Oh! it’s so desolate. So empty. Everything’s so changed. Even the Hollow is different and the squirrels seem like strangers. If he had to go, why did he ever, ever come!”

“Why, indeed!”

Mr. Dutton was surprised and frightened by the intensity of her grief. If she could sorrow in this way for a brief friendship, what untold misery might not life have in store for her? There must have been some serious blunder in his training if she were no better fitted than this to face trouble; and for the first time it occurred to him that he should not have kept her from all companions of her own age.

“Margot!”

The sternness of his tone made her look up and calm herself.

“Y-es, uncle.”

“This must stop. Adrian went by my invitation. Because I could no longer permit your association. Between his household and ours is a wrong beyond repair. He cannot help that he is his father’s son, but being such, he is an impossible friend for your father’s daughter. I should have sent him away at my very first suspicion of his identity, but—I want to be just. It has been the effort of my life to learn forgiveness. Until the last I would not allow myself even to believe who he was, but gave him the benefit of the chance that his name might be of another family. When I did know—there was no choice. He had to go.”

Margot watched his face as he spoke, with a curious feeling that this was not the loved and loving uncle she had always known, but a stranger. There were wrinkles and scars she had never noticed, a bitterness that made the voice an unfamiliar one, and a weariness in the droop of the figure leaning upon the hoe which suggested an aged and heartbroken man.

Why, only yesterday, it seemed, Hugh Dutton was the very type of a stalwart woodlander, with the grace of a finished and untiring scholar, making the man unique. Now, if Adrian had done this thing, if his mere presence had so altered her beloved guardian, then let Adrian go! Her arms went round the man’s neck and her kisses showered upon his cheeks, his hands, even his bent white head.

“Uncle, uncle! Don’t look like that! Don’t. He’s gone and shall never come back. Everything’s gone, hasn’t it? Even that irreparable past, of which I’d never heard. Why, if I’d dreamed, do you suppose I’d even ever have spoken to him? No, indeed. Why, you, the tip of your smallest finger, the smallest lock of your hair, is worth more than a thousand Adrians! I was sorry he treated me so rudely, but now I’m glad, glad, glad. I wouldn’t listen to him now, not if he said good-by forever and ever. I love you, uncle, best of all the world, and you love me. Let’s be just as we were before any strangers came. Come, let’s go out on the lake.”

He smiled at her extravagance and abruptness. The times when they had gone canoeing together had been their merriest, happiest times. It seemed to her that it needed only some such outing to restore the former conditions of their life.

“Not to-day, dearest.”

“Why not? The potatoes won’t hurt, and it’s so lovely.”

“There are other matters, more important than potatoes. I have put them off too long. Now—Margot, do you love me?”

“Why—uncle?”

“Because there is somebody whom you must love even more dearly. Your father.”

“My—father! My father? Of course; though he is dead.”

“No, Margot. He is still alive.”

PIERRE’S ill temper was short-lived, but his curiosity remained. However, when Adrian steadily refused to gratify it his interest returned to himself.

“Say, I’ve a mind to go the whole way.”

“Where?”

“Wherever you’re going. Nothing to call me back.”

“Madoc?”

“We might take him along.”

“Not if he’s sick. That would be as cruel to him as troublesome to us. Besides, you need go no further than yonder shore.”

“Them’s the woods you got lost in.”