The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Japanese New Year’s Festival, Games and Pastimes, by Helen Gunsaulus

Title: The Japanese New Year’s Festival, Games and Pastimes

Author: Helen Gunsaulus

Release Date: December 30, 2021 [eBook #67056]

Language: English

Produced by: Ronald Grenier (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/University of Illinois Libraries)

BY

HELEN C. GUNSAULUS

Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology

FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

CHICAGO

1923

{1}

Field Museum of Natural History

Department of Anthropology

Chicago, 1923

Leaflet Number 11

The Japanese New Year’s Festival, Games and Pastimes

The Japanese prints with which we are most familiar in this country are those known as nishikiye, literally “brocade picture.” Generally speaking, they are portraits of actors and famous beauties or landscapes and nature studies. There are, however, other woodcuts known as surimono, “things printed,” whose subjects are characters known in history and folklore, household gods, incidents in the daily life of the people and the celebration of certain festivals, particularly that of the New Year. From a careful study of these prints we may become acquainted with many of the most distinctive customs of Japan.

Though produced by the same process as that used for the nishikiye, surimono may be easily distinguished from the former. In addition to the series of wood blocks used to print the outline and colors of the design, surimono are often enriched by the application of metal dusts and embossing. The decorative motive is usually interpreted or accompanied by a poem or series of poems written in the picture. These prints were not made for sale but were exchanged as gifts among poets and artists on certain occasions, such as feasts, birthdays, theatrical or literary meetings, and especially as cards of greeting presented at the opening of the New Year. The surimono in the{2} collection in Field Museum of Natural History were selected primarily with the view of illustrating the customs and mode of living of the people of Japan rather than of assembling together pictures which would be enjoyed for their aesthetic appeal. While these prints are of an artistic nature, they are valuable to an institution of this kind as approaches to the study of the ethnology of Japan. The Museum is in possession of a collection of three hundred and sixty prints which has been divided into four groups, in the first of which the New Year’s festival and certain games and pastimes are pictured to a considerable degree. This selection is hung each year in Gunsaulus Hall (Room 30, Second Floor) from January 1st to April 1st, when it is succeeded by another group.

THE NEW YEAR’S FESTIVAL

Of the many festivals enjoyed in Japan, none is attended with more ceremony than that which opens with the New Year and is celebrated with more or less formality for fourteen days. It was customary in the old days to celebrate the New Year at the time when the plum first blossomed and when winter began to soften into spring, somewhere between the middle of January and the middle of February. Since the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, this festival opens on January 1st, and is attended by many of the interesting ceremonies that were practised in former times. On the thirteenth day of the preceding month, a special stew (okotojiru) is made from red beans, potatoes, mushrooms, sliced fish and a root (konnyaku). About this time a cleaning of the house takes place. It is partly ceremonial and partly practical, and is known as “soot-sweeping” (susu-haraki). Servants are presented with gifts of money and a short holiday.

{3}

According to the lunar calendar, the New Year’s celebration was opened by the ceremony known as oniyarai, “demon-driving.” This occurred at Setsubun, the period when winter passed into spring, and to-day it is generally practised at that time and is quite independent of the New Year’s festival. In some sections of the country, however, it has been moved forward to New Year’s eve, December 31st. As may be seen in the first illustration, this ceremony consists of the scattering of parched beans in four directions in the house, crying at the same time, “Out with the devils, in with the good luck.” Though sometimes performed by a professional who goes from door to door, this office is generally carried on by the head of the family. The custom may be traced back to ancient days when the demons expelled personified the wintry influences and the diseases attendant on them. It is still customary in some regions to gather up beans equal in number to the age plus one, and wrap them with a coin in a paper which has been previously rubbed over the body, to transfer ill luck. This package is then flung away at a cross-roads, with the idea that thereby ill luck is gotten rid of. Again in other places some of the beans are saved and eaten at the time of the first thunder.

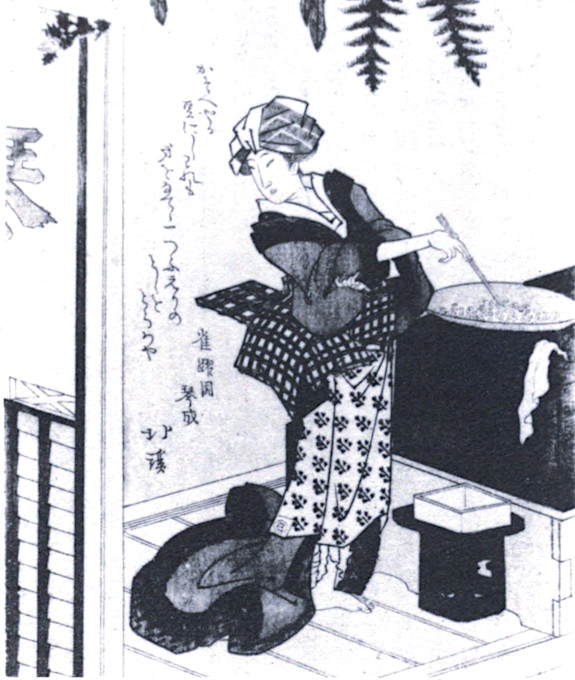

In Fig. 2 other interesting steps in the celebration may be studied. Certain preparations for the demon-expelling ceremony are being made. A woman who stands near a stove is parching the beans in a flat pan. At her feet the box for the beans rests upon a low stand of the form known as sambo, that used as the support for all ceremonial arrangements on festive occasions. It is made of cypress wood; in this case it is lacquered red but when holding offerings for the gods, it is left unstained. It will be noticed that there is a charm stuck in at the upper corner of the open{4} door in this picture. It is composed of a branch of holly on which is impaled the head of a sardine. This charm, which is always placed in the lintel after the demons have been driven out, is said to be repellent to evil influences and the prickly holly has the property of keeping demons from reëntering the house.

Immediately over the woman’s head hangs one of the most conspicuous objects associated with the New Year’s festival. It is the straw rope (shimenawa) which is stretched before the entrance at the front of the house, to remain during all the days of the celebration, and keep out all evil spirits. Smaller straw ropes are placed over inner doorways and before the household shrine or god-shelf (kami-dana). They are also to be seen on the posts of certain bridges, particularly the Gojōbashi in Kyōto. The shimenawa is always made of straw twisted to the left, the pure or fortunate side, with pendant straws at regular intervals but of differing numbers in the order three, five, seven, along the whole length of the strand. Alternating with these pendants are leaves of the fern, urajiro. Since the fern-fronds spring in pairs from the stem, this plant is symbolic of happy married life and increase. The lanciform leaves attached to the straw rope in this picture, are those of a laurel-like shrub called yuzuri. This plant has been adopted as the symbol of a long united family because the old leaves cling to the branch after the young ones have appeared. Other objects with specific meanings are often attached to the rope, the most common being paper cuttings (gohei) which represent the offerings of cloth made to the gods in ancient times. Occasionally tied to the rope are little bundles of charcoal (sumi) which, because of its changeless color, symbolizes changelessness.

FIG. 1. ONIYARAI CEREMONY.

BY HOKKEI.

FIG. 2. PREPARING BEANS FOR ONIYARAI.

BY HOKKEI.

The origin of the use of shimenawa on New Year’s day may be traced back to mythological times{5} when the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu, was tempted forth from the cave into which, through fear of her brother, she had retired. In order to entice her from her hiding place, all the gods assembled together and, bringing with them a dancer, made such a commotion that the “heavenly ancestor of the emperor” peeped out. Her face was reflected in a mirror which they had hung upon a tree. Never before had she gazed upon her own beauty, and thinking it the countenance of a rival, she stepped forth. She was prevented from returning by a fellow deity who stretched a straw rope across the opening of her retreat. During her retirement all the earth had been in darkness. As she emerged, the warm light of the sun spread over the world and joy returned to the people.

A survival of the belief in this legend is to be seen to this day at a certain spot on the shore of Owari Bay. There, at Futami, two tower-like rocks, known at the “Husband and Wife Rocks” (Myōto-seki) jut out of the waves close to the beach. They are joined together by a straw rope which some say represents the bond of conjugal union. Others see in it a hindrance against the entrance of the Plague God. However, these rocks are popularly thought to represent the cave into which the Sun Goddess retired. On this account many people journey to Myōto-seki before dawn on New Year’s day, in order to see the first rays of the sun emerge on the horizon between these two rocks, thereby witnessing the re-appearance of the Sun Goddess who is restrained by the shimenawa from re-entering her retreat.

The fern leaves and yuzuriha, attached to the straw rope, are also in evidence on certain ceremonial arrangements which are to be seen in all households on New Year’s day. Two such objects are illustrated in Fig. 3. They are called o kazari mono, “honorably{6} decorated thing.” Both of these stands of sambo form are laid with paper covers on which are placed rice puddings (mochi) of various forms. Those on the stand at the left are large, flat and round, in shape representing the mirror into which Amaterasu looked when she came forth from the cave. Again they symbolize the sun, the yo or male principle, and the moon, the in or female principle. They are adorned with two fern leaves, a folded paper arrangement (called noshi) and a bitter orange (daidai) to which are attached two yuzuri leaves. The Japanese are devoted to puns on words. Daidai-yuzuri, in pronunciation, is identical with the phrase which means “bequeath from generation to generation,” hence the adoption of the bitter orange with the yuzuri leaves in the New Year’s decoration. Dried chestnut kernels (kachiguri) are often added to the arrangement, for the name suggests the happy thought of victory (kachi). The second stand which holds rice puddings is surmounted by a branch of pine, one of the well-known emblems of longevity. The pine, bamboo and plum are arranged together for this occasion and are known as sho-chiku-bai. At the base of the pine in Fig. 3 and lying on fern leaves, is a lobster. On account of the bent back and long tentacles it typifies a life so prolonged that the body is bent over and the beard reaches to the waist. A lobster or crayfish is often seen hanging to the center of the straw rope.

In the background of this picture, a set of bows and arrows used for indoor practice may be seen leaning against a basket filled with square rice cakes. In the foreground, a woman is seated before a chopping board on which she cuts the rice cakes into small pieces. Being small and hard, these bits are known as “hail mochi.” In some parts of Japan, it is customary{7} to eat them on the third day of the festival. A companion who holds up a picture of the Sun Goddess, is seated near a lantern, on the base of which rests a waterpot. It is likely that this vessel contains the “young water” (hatsumizu) used for the New Year’s tea (fuku cha, “good luck tea”). Custom decrees that this water must be drawn from the well before the sun’s rays strike it. An offering of rice is sometimes first thrown into the well. With the tea is served a preserved plum (umeboshi), which, because of its wrinkled skin, suggests the hope of a good old age. In addition, there is always served on this festive day a fish stew known as zoni, and a special spiced brand of wine called toso. In some households the first day is devoted entirely to family devotion. Before the ancestral shrine offerings of tea, mirror dumplings, zoni and toso are placed, and then each living member is served in order of age with the same viands. With the same respect for age, New Year’s greetings are spoken first to the shrine, then to grandparents and parents and so on down to the smallest child.

As we leave the house and go outdoors, we see before all portals the “pine of the doorway” (kado-matsu)—pine and bamboo saplings bound together and set up at either side of the entrance. The pine on the left has a red trunk and is of the species akamatsu (pinus densiflora); that on the right has a black trunk and is the kuro-matsu (pinus thunbergii). Fancy has attributed to the lighter pine, the feminine sex, while the black pine is thought to represent the masculine. Between these kadomatsu is usually hung the straw rope previously described. The two plants, the pine and bamboo, have no religious significance but are emblematic of longevity and fidelity. Long life and vigor are naturally suggested by{8} the old and gnarled evergreens; the reason why the bamboo should typify fidelity is less obvious. It is again a case of a similar pronunciation of two Chinese characters: setsu meaning fidelity and setsu denoting the node of the bamboo. A kado-matsu is pictured in the fourth illustration where in the foreground two boys, bound together with a rope are testing their strength. This common pastime for boys is called kubi hiki. A third child, acting as umpire, holds in his hand a kite in the shape of a bird.

The streets during the New Year’s festival are veritable playgrounds; stilt walking, rope pulling and jumping, top spinning and ball playing are all indulged in. Kite-flying is perhaps the most conspicuous sport, for kites of many shapes and sizes are sent up by all lads on these days. In Japan kite-flying is not only more picturesque than with us, on account of the use of such fantastic forms as double fans, birds, butterflies, cuttlefish or huge portraits of heroes in brilliant colors and unusual proportions, but it is also apt to be a very exciting sport. Occasionally opponents try to capture an enemy’s kite. Competitive kite-flying is accomplished by covering the first ten or twenty feet of the kite string with fish glue or rice paste, and then dipping it into pounded glass or porcelain. On hardening, this portion of the string becomes a series of tiny blades which when crossed with another string at high tension can soon saw away the kite of the adversary. It is also customary to attach a strip of whale bone or a bow of bamboo to the large kites, so that on ascending a loud humming is produced which adds to the excitement of the flight. Only boys and men fly kites in Japan.

FIG. 3. SAMBO AND MOCHI FOR NEW YEAR

BY I-ITSU GETCHI ROJIN.

FIG. 4. KADO-MATSU, KITE AND ROPE PULLING.

BY HOKKEI.

The girls, dressed in their best costumes, are picturesque as they play with a hand ball and at battledore and shuttlecock. The balls are made of paper and{9} wadding wound with silk of different colors. The battle boards are of a white wood called kiri and are often elaborate affairs, adorned on one side with the portrait of a hero made of colored silks. The shuttlecock is composed of the seed of the soapberry, to which bright feathers are attached. On a surimono in this exhibition two girls are at play upon a red mat spread beneath the blossoming plum tree. To one of the branches is clinging a nightingale, the bird which heralds the approach of spring. All of the poems on this surimono treat of the New Year and the nightingale’s song. One, literally translated, reads, “Spring’s first wind melting the snow, let laugh the plum, let cry the nightingale.” Another rendered in English is as follows: “Like the comical manner of a bouncing ball, the nightingale’s song rolls (like a ball) on the plum branch.”

Young maidens carrying flat bamboo baskets make excursions into the country to gather the seven spring grasses (nanakusa). These greens, the water drop-wort, shepherd’s purse, radish, celery, dead-nettle, turnip and rock-cress, are the components which are needed for the celebration of the first of the five festivals known as Go-sekku. This one occurs on the seventh day of the first month.

While the young people enjoy these pastimes out of doors, within the house the older members of the family indulge in the writing of a New Year’s poem or in playing one of the games described in the next section of this leaflet. The writing of poems at this auspicious time is almost universal, indeed, the composing of poetry and the mastery of caligraphy are considered as necessary accomplishments for the cultured person. The most common form of New Year’s poem is that known as tanka. It is a poem of five lines, the first and third of which contain five syllables,{10} the other three seven, and is the poem almost always found on surimono. Poems are often inscribed on fans as in Fig. 5, where one young woman meditates over the verse which she has written on a fan. A companion seated at a writing table, is grinding ink with one hand and holding with the other a poem paper (tanzaku). Such long strips are to be seen in many houses awaiting the New Year’s inspiration. They are sometimes tinted to a soft shade or ornamented with appropriate New Year’s flowers or with silver clouds as in this case. One of the poems accompanying this surimono is worthy of translation: “From the window, lighting the brush for the first writing, the plums’ fragrance on the wind is blowing.”

On the first day of the year, musicians and dancers proceed from house to house. The musician, wearing a flat straw hat which partially covers her face, charms away birds of ill omen with a few strains played on the samisen. The dancers are either those known as manzai or are those who enact the lion dance, a performance adopted from China. (Costumes used in the lion dance of China may be seen in Case 5, Hall I, ground floor.) With the majority of families much of the day is spent in paying visits to friends, at which times it is customary to present small gifts, usually of trifling value such as conserves, fruit, fish, persimmons, herring roe, bean-curd, towels and similar articles. Presents are either placed on trays in ceremonial form or carefully wrapped in paper or silk and tied with red and white cords.

Accompanying every gift there is always a quiver-shaped envelope of folded paper called noshi, in which is inserted a strip of dried haliotis or awabi. This odd custom, like so many others, has an interesting significance. The strip of haliotis is symbolic of long life and durability of affection, because it is{11} capable of being stretched to great length. The single shell of this mollusk also suggests singleness of affection. In the ancient days when Japan was a nation of fishermen, a piece of dried awabi was indeed a valuable gift. In the present use of the noshi and awabi, some say that the Japanese would recall the primitive days, thereby preserving the virtue of humility. Another conspicuous object which is usually in evidence at New Year’s is the small treasure boat (takarabune) sometimes made of straw and symbolizing the coming of the “Seven Gods of Good Luck” Shichifukujin. Pictures of takarabune are placed beneath the pillow with the wish that the New Year’s dream may be a fortunate one.

No work is done on the first day of the festival, even the sweeping of the house is omitted, lest some good fortune be scattered to the winds. All stores are closed to regular business. On the second day a pretense is made toward returning to normal life. The musician takes out his instrument, the student looks into his books, the artist gets out his brushes and the merchant distributes his goods from gaily colored handcarts. The storehouse of treasures is opened and enjoyed on this day as well, rarely on the first day for fear good fortune and wealth should flee away. The large mirror dumplings are taken from the ceremonial stands and from before the family shrine on the fourth day, and cut into small pieces known as “teeth-strengtheners.” On this day also, the fire brigades of Tōkyō march in procession and perform gymnastic feats. At early dawn on the seventh day the master of the house, who follows the old customs closely, arises and goes to the kitchen where he washes the seven spring herbs (nanakusa) in the first water drawn from the well. He then chops them on a board, moving his knife in time with a certain{12} incantation concerned with cheating any birds of ill omen which might come to the country. The chopped herbs are boiled in a kind of rice gruel and served with ceremony at the breakfast. On the eleventh day the military men used to offer mirror dumplings before their armor. The long celebration of the festival is finally brought to a close with the burning of the kado-matsu and other decorations on the fourteenth or fifteenth day of the first month.

GAMES AND PASTIMES

Several of the most popular games of Japan are represented on surimono and only those games will be mentioned herein. To those who would study the subject exhaustively, S. Culin’s “Corean Games” is recommended. With the possible exception of chess (shogi), no game is more widely played than go, which has been erroneously identified with the game gobang, somewhat similar to our game of checkers. Go, a far more difficult contest than that European game, was introduced into Japan from China in the eighth century. For generations it has occupied the attention of the Japanese, there being clubs and schools devoted to the playing of go. It is played on a square, raised wooden board on which nineteen straight lines drawn from one side to the other of the board cross nineteen other lines drawn at right angles, making three hundred and sixty-one crosses on which the men are placed. One hundred and eighty white, and one hundred and eighty-one black stones, are used in the playing. These represent respectively day and night; the crosses represent three hundred and sixty degrees of latitude and the central intersection stands for the primordial principle of the universe. The object of the game is to capture the opponent’s pawns by enclosing at least three crosses around his stone, and to{13} cover as much of the table as possible. Military men have always been devotees to the game of go, seeing in it the rudimentary tactics necessary for successful warfare.

FIG. 5. THREE GIRLS WRITING NEW YEAR’S POEMS.

BY KATSUCHIKA HOKUSAI.

FIG. 6. GAME OF JUROKU MUSASHI.

BY HOKUSAI SORI.

Juroku musashi (“sixteen knights”) is a favorite New Year’s game which is illustrated in Fig. 6. It is played on a board divided into diagonally-cut squares. One player holds sixteen round paper pawns representing sixteen knights; the opponent has but one large piece known as the general (taisho) which has the power to capture enemy pieces when they are immediately on each side of it with a blank space beyond. The holder of the smaller pieces seeks to completely hedge in and thereby capture the big piece.

Sugoroku (“double sixes”) is similar to the European “race-game.” It is played with dice and the succeeding spaces on the board generally represent the stations of a journey. Brinkley, in his Japan and China (Vol. VI, p. 56), tells us that this game was imported from India in the eighth century and was at first prohibited on account of its gambling character. Eventually the Buddhist priests took it up and converted it into an instrument for inculcating virtue by making the spaces on the board represent a ladder of moral precepts which marked the path to victory. Sugoroku, with the travel board, is commonly played by children at New Year’s time. The name is also given to the more difficult game of backgammon which may be studied in one of the surimono in this museum. The board on which the game is being played is now obsolete. It is divided longitudinally into two fields with an intervening space between. Each field has twelve narrow subdivisions in which the men are placed.

Games of cards (karuta from the Spanish carta) are altogether different from the European card{14} games, though it is commonly supposed, on account of the derivation of this name, that card playing was introduced in the sixteenth century by Portuguese travelers. It is interesting to note here that card playing was known in China in the twelfth century. It would seem that Japan must have made her first contact with the game through a source other than Spain, for the majority of the forms and methods of her playing cards in no way reflect European influence. The fact that cards are quite often called fuda (“ticket”) would also add in casting doubt on the European origin. The hana-garuta or “flower cards” which are widely played are small in size, black on the backs and adorned on the face with flowers and emblems belonging to the twelve months. A set comprises forty-eight cards and the values vary from one to twenty points. The game consists in drawing, playing and matching in suits or in groups.

In the game of uta garuta (“poem cards”), there are two hundred cards. One hundred of these are decorated with portraits of poets and the first two lines of famous classic verses. These are to be matched with the corresponding hundred on which the remaining lines of the poems are inscribed. Of the many ways of playing uta garuta, chirashi, “spread out,” is the most exciting. The cards bearing the last part of the poems are laid face up on the floor. Those inscribed with the first lines are held by the “reader,” who reads them aloud one by one. The other players strive to pick up the corresponding card and he who at the last holds the most is declared winner.

Somewhat similar to uta garuta is the game of kai awase (“shell matching”). Three hundred and sixty bivalve shells are used for this game. The two sides are separated and on the upper half is painted a portrait of a poet, on the mated shell are the lines{15} of one of his poems. Other sets have only the poems inscribed within them, the two first lines being on one half shell, the remaining lines on the other. The shells are divided among the players, and as the pictures or first lines are laid upon the mats, the holder of the corresponding poem places his shell near it. Some of the old kai awase sets were of great beauty and were stored in circular lacquer cases of fine workmanship. This game and the uta garuta naturally were played only by the cultured classes and were vehicles for the learning of the classics.

In addition to the kites and battledores, stilts and hand balls, there are represented in this selection of surimono other toys for children such as hobby horses, dolls of paper, swinging bats for ball playing, archery outfits and the amusements afforded by caged singing insects and trained mice and monkeys. The older people likewise have delightful pastimes. As the season advances they spend much time in enjoying nature, the viewing of blossoming trees and plants, the listening to singing insects in the evening, and the gathering of shells and shell fish at ebb-tide are all occasions of organized parties in which men as well as women take keen pleasure. A series of five surimono by Kuniyoshi realistically portrays the joys of an ebb-tide party.

Most of the musical instruments, which both men and women enjoy playing, are importations from China, particularly the lyre (koto), the violin (kokyū) and the reed organ (shō). The samisen, a three-stringed guitar, is the popular accompaniment of the singing girl or geisha; the koto is played by the more aristocratic women. Drums of double conical form (tsuzumi) are to be seen in the hands of both men and women. Flutes have long been popular with men of all classes, the wandering minstrel, the court musician{16} and even the courtier himself who delighted to match the softness of his flute tone with the gentle light of the moon, or with the voice of the harbinger of spring as evidenced by the poem on Fig. 7 which reads: “Like the nightingale’s voice above the clouds, hazed over by the mist, the flute contains sweetness.”

Even more aesthetic than the enjoyment of music are the arts of the ceremonial tea (cha no yu, “hot-water-tea”) and that of flower arrangement (ikebana), both of which up to a short time ago were thought to be necessary acquirements for the cultivated classes. To each of these sciences many schools were devoted. Only the barest sketch can here be given of these subjects to which volumes have been devoted. The tea ceremony to-day is rigorously outlined by complicated rules as to utensils, order of procedure and even as to the subjects of conversation indulged in while in the tea room.

Tea drinking was introduced from China in the ninth century and at first was practised by the Buddhist priests for medicinal purposes and especially as a means of keeping awake during meditations. In the fifteenth century meetings for tea drinking were held in groves and gardens. In an adjoining tea house pictures were shown on these occasions which were mainly Buddhistic in subject, and most of them of Chinese origin. Under the great tea-master Rikyū (sixteenth century) the rules of cha no yu were rewritten. From this time on the ceremony was performed in a small house with a low door through which the few guests would have to prostrate themselves for entrance. The most characteristic traits of these gatherings were a close sympathy with nature and a love of simplicity almost amounting to ruggedness as expressed in the tea bowls often partially glazed. Restraint was likewise displayed in the decorations{17} of the room, a simple bamboo flower holder was preferred to the bronze vase, and a hanging picture (kakemono) was chosen which would make an equally quiet appeal, such as a branch in the wind or an example of fine caligraphy. The occasion became a time in which to worship purity and refinement.

FIG. 7. NOBLEMAN PLAYING THE FLUTE.

BY GAKUTEI.

FIG. 8. YOUNG MAN ARRANGING FLOWERS.

ARTIST UNKNOWN.

Like the tea ceremony, the art of flower arrangement (ikebana) developed into a philosophy under the patronage of the shōgun Yoshimasa in the fifteenth century. For several centuries it has been studied and cultivated as a refined accomplishment. Miss Averill in “Japanese Flower Arrangement” tells us that many of Japan’s most celebrated generals have been masters of this art, finding that it calmed their minds and made clear their decisions for the field of action. All of the schools of ikebana, with one exception, are founded on the same principles. The underlying idea is to reproduce in the arrangement the effect of growing plants and to preserve for as long a time as possible the life of the plants. Arrangements aim to reflect the season or the occasion. When high winds prevail in March, branches with unusual curves are selected and so placed as to suggest strong breezes. Certain colors are considered unlucky for certain occasions, for example, red suggesting flames is inappropriate for house warmings, when white would be the desirable color in that it suggests water to quench the fire. An uneven number of flowers are considered lucky and also much more suggestive of the processes of nature, where there is seldom found perfect symmetry and actual balance. In the arrangements of the later schools there are always represented three principles known in the different groups by diverse names: “Heaven, Man and Earth;” “Earth, Air and Water;” or “Father, Mother and Child.” The three main sprays of an arrangement represent in their directions{18} of growth these three principles, and are designated: “standing, growing, running.” Subsidiary branches in the selection are called attributes. As may be seen in Fig. 8, an arrangement is first composed in the hands, care being taken that all branches be kept close together at the base so as to form “the parent stalk”. The young man in the picture holds in his mouth a support for bracing the flowers in the bronze vase, on the floor are scissors. A woman is approaching with a waterpot. Such a refined pastime as ikebana is primarily intended to entertain visitors who may contemplate the finished arrangement as it is set up in the raised portion (tokonoma) of the main room.

Helen C. Gunsaulus

Transcriber’s Notes.

Text notes:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.