The Project Gutenberg eBook of Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXI, No. 3, September 1842, by Various

Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXI, No. 3, September 1842

Author: Various

Editors: George Rex Graham

Rufus W. Griswold

Release Date: May 3, 2022 [eBook #67983]

Language: English

Produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net from page images generously made available by the Internet Archive

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXI. September, 1842 No. 3.

Contents

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXI. PHILADELPHIA: SEPTEMBER, 1842. No. 3.

———

BY HENRY W. LONGFELLOW.

———

What’s done we partly may compute,

But know not what’s resisted.

Burns.

Victorian, Student of Alcalá.

Hypolito, Student of Alcalá.

Count of Lara, Gentleman of Madrid.

Don Carlos, Gentleman of Madrid.

The Arch-Bishop of Toledo.

A Cardinal.

Beltran Cruzado, Count of the Gipsies.

Padre, Cura of El Pardillo.

Pedro Crespo, Alcalde.

Pancho, Alguacil.

Francisco, Valet.

Chispa, Valet.

Preciosa, a Gipsy girl.

Angelica, a poor girl.

Martina, Padre Cura’s niece.

Dolores, Preciosa’s maid.

Gipsies and Musicians.

Scene I.—The Count of Lara’s chambers. Night. The Count in his dressing-gown, smoking and conversing with Don Carlos.

Lara. You were not at the play to-night, Don Carlos;

How happens it?

Don Carlos. I had engagements elsewhere:

Pray who was there?

Lara. Why, all the town and court.

The house was crowded; and the busy fans

Among the gaily dressed and perfumed ladies

Fluttered like butterflies among the flowers.

There was the Countess of Medina Celi;

The Goblin Lady with her Fantom Lover,

Her Lindo Don Diego; Doña Sal,

And Doña Serafina, and her cousins.

But o’er them all the lovely Violante

Shone like a star, nay, a whole heaven of stars.

Don Carlos. What was the play?

Lara. It was a dull affair.

One of those comedies in which you see,

As Lopè says, the history of the world

Brought down from Genesis to the day of judgment.

There were three duels in the first tornada,

Three gentlemen receiving deadly wounds,

Laying their hands upon their hearts and saying

O I am dead! A lover in a closet,

An old hidalgo, and a gay Don Juan,

A Doña Inez with a black mantilla

Followed at twilight by an unknown lover,

Who looks intently where he knows she is not!

Don Carlos. Of course the Preciosa danced to-night?

Lara. And ne’er danced better. Every footstep fell

As lightly as a sunbeam on the water.

I think the girl extremely beautiful.

Don Carlos. Almost beyond the privilege of woman!

I saw her in the Prado yesterday.

Her step was royal—queen-like—and her face

As beauteous as a saint’s in Paradise.

Lara. May not a saint fall from her Paradise,

And be no more a saint?

Don Carlos. Why do you ask?

Lara. Because ’tis whispered that this angel fell;

And though she is a virgin outwardly,

Within she is a sinner; like those panels

Or doors and altar-pieces, the old monks

Painted in convents, with the Virgin Mary

On the outside, and on the inside Venus!

Don Carlos. Nay, nay! you do her wrong.

Lara. Ah! say you so?

Don Carlos. She is as virtuous as she is fair;

A very modest girl, and still a maid.

Lara. You are too credulous. Would you persuade me

That a mere dancing girl, who shows herself

Nightly, half-naked, on the stage for money,

And with voluptuous motions fires the blood

Of inconsiderate youth, is to be held

A model for her virtue?

Don Carlos. You forget

That she’s a gipsy girl.

Lara. And therefore won

The easier.

Don Carlos. Nay, not to be won at all!

The only virtue that a gipsy prizes

Is chastity. That is her only virtue.

Dearer than life she holds it. I remember

A gipsy woman, a vile, shameless bawd,

Whose craft was to betray the young and fair;

And yet this woman was above all bribes.

And when a noble lord, touched by her beauty,

The wild and wizard beauty of her race,

Offered her gold to be what she made others,

She turned upon him, with a look of scorn,

And smote him in the face!

Lara. Most virtuous gipsy!

Don Carlos. Nay, do not mock me. I would fain believe

That woman, in her deepest degradation,

Holds something sacred, something undefiled,

Some pledge and keepsake of her higher nature,

And, like the diamond in the dark, retains

Some quenchless gleam of the celestial light!

Lara. Yet Preciosa would have taken the gold.

Don Carlos. (rising.) You will not be persuaded!

Lara. Yes; persuade me.

Don Carlos. No one so deaf as he who will not hear!

Lara. No one so blind as he who will not see!

Don Carlos. And so good night. I wish you pleasant dreams,

And greater faith in woman.— [Exit.

Lara. Greater faith!

Thou shallow-pated fool! Do I not know

Victorian is her lover?

Enter Francisco with a casket.

Well, Francisco,

What speed with Preciosa?

Fran. None my lord.

She sends your jewels back, and bids me tell you

She is not to be purchased by your gold.

Lara. Then I will try some other way to win her.

Pray dost thou know Victorian?

Fran. Yes, my lord;

I saw him at the jeweller’s to-day.

Lara. What was he doing there?

Fran. I saw him buy

A golden ring, that had a ruby in it.

Lara. Was there another like it?

Fran. One so like it

I could not choose between them.

Lara. It is well.

To-morrow morning bring that ring to me.

Do not forget. Now light me to my bed. [Exeunt.

Scene II.—A street in Madrid. Night. Enter Chispa, followed by musicians, with a bag-pipe, guitars, and other instruments.

Chispa. Abernuncio Satanas! and a plague on all lovers who ramble about at night, drinking the elements instead of sleeping quietly in their beds. Every dead man to his cemetery, say I; and every friar to his monastery. Now, here’s my master, Victorian, yesterday a cow-keeper and to-day a gentleman; yesterday a student and to-day a lover; and I must be up later than the nightingale, for as the abbot sings so must the sacristan respond. God grant he may soon be married, for then shall all this serenading cease. Man is fire, and woman is tow, and the devil comes and blows; and, therefore, I have heard my grandmother say, that if your neighbor has a son, wipe his nose and marry him to your daughter. Aye! marry! marry! marry! Mother, what does marry mean? It means to spin, to bear children, and to weep, my daughter! And of a truth there is something more in matrimony than cake and kid gloves. (To the musicians.) And now, gentlemen, Pax vobiscum! as the ass said to the cabbages. Pray walk this way; and don’t hang down your heads. It is no disgrace to have an old father and a ragged shirt. Now, look you, you are gentlemen who lead the life of crickets; you enjoy hunger by day and noise by night. Yet, I beseech you, for this once be not loud, but pathetic; for it is a serenade to a damsel in bed, and not to the man in the moon. Your object is not to arouse and terrify, but to soothe and bring lulling dreams. Therefore, each shall not play upon his instrument as if it were the only one in the universe, but gently, and with a certain modesty, according with the others. Pray, how may I call thy name, friend?

First Musician. Geronimo Gil, at your service.

Chispa. Every tub smells of the wine that is in it. Pray, Geronimo, is not Saturday an unpleasant day with thee?

First M. Why so?

Chispa. Because I have heard it said that Saturday is an unpleasant day for those who have but one shirt. Moreover, I have seen thee at the tavern, and if thou canst run as fast as thou canst drink, I should like to hunt hares with thee. What instrument is that?

First M. An Aragonese bag-pipe.

Chispa. Pray, art thou related to the bag-piper of Bujalance, who asked a maravedi for playing and ten for leaving off?

First M. No, your honor.

Chispa. I am glad of it. What other instruments have we?

Second and Third M. We play the bandurria.

Chispa. A pleasing instrument. And thou?

Fourth M. The fife.

Chispa. I like it; it has a cheerful, soul-stirring sound, that soars up to my lady’s window like the song of a swallow. And you others?

Other Musicians. We are the singers, please your honor.

Chispa. You are too many. Do you think we are going to sing mass in the Cathedral of Cordova? Four men can make but little use of one shoe, and I see not how you can all sing in one song. But follow me along the garden wall. That is the way my master climbs to the lady’s window. It is by the vicar’s skirts that the devil climbs into the belfry. Come, follow me and make no noise. [Exeunt.

Scene III.—Preciosa’s Chamber. She stands by the open window.

Preciosa. How slowly through the lilac-scented air

Descends the tranquil moon! Like thistle-down

The vapory clouds float in the peaceful sky:

And sweetly from yon hollow vaults of shade

The nightingales breathe out their souls in song,

Flattering the ear of night. And hark! what sounds

Answer them from below!

Serenade.

Stars of the summer night!

Far in yon azure deeps,

Hide, hide your golden light,

She sleeps!

My lady sleeps!

Sleeps!

Moon of the summer night!

Far down yon western steeps,

Sink, sink in silver light!

She sleeps!

My lady sleeps!

Sleeps!

Wind of the summer night!

Where yonder woodbine creeps,

Fold, fold your pinions light!

She sleeps!

My lady sleeps!

Sleeps!

Dreams of the summer night!

Tell her, her lover keeps

Watch! while in slumber light

She sleeps!

My lady sleeps!

Sleeps!

Enter Victorian by the balcony.

Victorian. Poor little dove! Thou tremblest like a leaf!

Pre. I am so frightened!—’Tis for thee I tremble!

I hate to have thee climb that wall by night!

Did no one see thee?

Vic. None, my love, but thou.

Pre. ’Tis very dangerous; and when thou’rt gone

I chide myself for letting thee come here

Thus stealthily by night. Where hast thou been?

Since yesterday I have no news from thee.

Vic. Since yesterday I’ve been in Alcalá.

Ere long the time will come, sweet Preciosa,

When that dull distance shall no more divide us;

And I no more shall scale thy wall by night

To steal a kiss from thee, as I do now.

Pre. An honest thief, to steal but what thou givest.

Vic. And we shall sit together unmolested,

And words of true love pass from tongue to tongue,

As singing birds from one bough to another.

Pre. That were a life indeed to make time envious!

I knew that thou wouldst visit me to-night.

I saw thee at the play.

Vic. Sweet child of air!

Never did I behold thee so attired

And garmented in beauty, as to-night!

What hast thou done to make thee look so fair?

Pre. Am I not always fair?

Vic. Aye, and so fair,

That I am jealous of all eyes that see thee,

And wish that they were blind.

Pre. I heed them not;

When thou art present, I see none but thee!

Vic. There’s nothing fair nor beautiful, but takes

Something from thee, that makes it beautiful.

Pre. And yet thou leav’st me for those dusty books.

Vic. Thou com’st between me and those books too often!

I see thy face in every thing I see!

The paintings in the chapel wear thy looks,

The canticles are changed to sarabands,

And with the learned doctors of the schools

I see thee dance cachuchas.

Pre. In good sooth,

I dance with the learned doctors of the schools

To-morrow morning.

Vic. And with whom, I pray?

Pre. A grave and reverend Cardinal, and his Grace

The Archbishop of Toledo.

Vic. What mad jest

Is this?

Pre. It is no jest. Indeed it is not.

Vic. Pr’ythee, explain thyself.

Pre. Why simply thus.

Thou knowest the Pope has sent here into Spain

To put a stop to dances on the stage.

Vic. I’ve heard it whispered.

Pre. Now the Cardinal,

Who for this purpose comes, would fain behold

With his own eyes these dances: and the Archbishop

Has sent for me.

Vic. That thou may’st dance before them.

Now viva la cachucha! It will breathe

The fire of youth into these gray old men,

And make them half forget that they are old!

’Twill be thy proudest conquest!

Pre. Saving one.

And yet I fear the dances will be stopped,

And Preciosa be once more a beggar.

Vic. The sweetest beggar that e’er asked for alms;

With such beseeching eyes, that when I saw thee

I gave my heart away!

Pre. Dost thou remember

When first we met?

Vic. It was at Cordova,

In the Cathedral garden. Thou wast sitting

Under the orange-trees, beside a fountain.

Pre. ’Twas Easter-Sunday. The full-blossomed trees

Filled all the air with fragrance and with joy.

The priests were singing, and the organ sounded,

And then anon the great Cathedral bell.

It was the elevation of the Host.

We both of us fell down upon our knees,

Under the orange boughs, and prayed together.

I never had been happy, till that moment.

Vic. Thou blessed angel!

Pre. And when thou wast gone

I felt an aching here. I did not speak

To any one that day.

Vic. Sweet Preciosa!

I lov’d thee even then, though I was silent!

Pre. I thought I ne’er should see thy face again.

Thy farewell had to me a sound of sorrow.

Vic. That was the first sound in the song of love!

Scarce more than silence is, and yet a sound.

Hands of invisible spirits touch the strings

Of that mysterious instrument, the soul,

And play the prelude of our fate. We hear

The voice prophetic, and are not alone.

Pre. That is my faith. Dost thou believe these warnings?

Vic. So far as this. Our feelings and our thoughts

Tend ever on, and rest not in the Present.

As drops of rain fall into some dark well,

And from below comes a scarce audible sound—

So fall our thoughts into the dark Hereafter,

And their mysterious echo reaches us.

Pre. I’ve felt it so, but found no words to say it!

I cannot reason—I can only feel!

But thou hast language for all thoughts and feelings.

Thou art a scholar: and sometimes I think

We cannot walk together in this world!

The distance that divides us is too great!

Henceforth thy pathway lies among the stars;

I must not hold thee back.

Vic. Thou little skeptic!

Dost thou still doubt?—What I most prize in woman

Is her affection, not her intellect!

Compare me with the great men of the earth—

What am I? Why, a pigmy among giants!

But if thou lovest—mark me! I say lovest—

The greatest of thy sex excels thee not!

The world of the affections is thy world—

Not that of man’s ambition. In that stillness

Which most becomes a woman, calm and holy,

Thou sittest by the fireside of the heart,

Feeding its flame. The element of fire

Is pure. It cannot change nor hide its nature,

But burns as brightly in a gipsy camp

As in a palace hall. Art thou convinced?

Pre. Aye, that I love thee, as the good love heaven,

But that I am not worthy of that heaven.

How shall I more deserve it?

Vic. Loving more.

Pre. I cannot love thee more; my heart is full.

Vic. Then let it overflow, and I will drink it,

As in the summer-time the thirsty sands

Drink the swift waters of a mountain torrent,

And still do thirst for more. (Kisses her.)

A Watchman in the street. Ave Maria

Purissima! ’Tis midnight and serene!

Vic. Hear’st thou that cry?

Pre. It is a hateful sound,

To scare thee from me!

Vic. As the hunter’s horn

Doth scare the timid stag, or bark of hounds

The moor-fowl from his mate.

Pre. Pray do not go!

Vic. I must away to Alcalá to-night.

Think of me when I am away.

Pre. Fear not!

I have no thoughts that do not think of thee.

Vic. (giving her a ring.) And to remind thee of my love, take this.

A serpent emblem of Eternity,

A ruby,—say, a drop of my heart’s blood.

Pre. It is an ancient saying, that the ruby

Brings gladness to the wearer, and preserves

The heart pure, and, if laid beneath the pillow,

Drives away evil dreams. But then, alas!

It was a serpent tempted Eve to sin.

Vic. What convent of barefooted Carmelites

Taught thee so much theology?

Pre. (laying her hand upon his mouth.) Hush! hush!

Good night! and may all holy angels guard thee!

Vic. Good night! good night! Thou art my guardian angel!

I have no other saint than thee to pray to!

(He descends by the balcony.)

Pre. Take care, and do not hurt thee. Art thou safe?

Vic. (from the garden.) Safe as my love for thee! But art thou safe?

Others can climb a balcony by moonlight

As well as I. Pray, shut thy window close;

I’m jealous of the perfumed air of night

That from this garden climbs to kiss thy lips.

Pre. (throwing down her handkerchief.) Thou silly child!

Take this to blind thine eyes.

It is my benison!

Vic. And brings to me

Sweet fragrance from thy lips, as the soft wind

Wafts to the out-bound mariner the breath

Of the beloved land he leaves behind.

Pre. Make not thy voyage long.

Vic. To-morrow night

Shall see me safe returned. Thou art the star

To guide me to an anchorage. Good night!

My beauteous star! My star of love, good night!

Pre. Good night!

Watchman. (at a distance.) Ave Maria Purissima!

Scene IV.—Victorian’s rooms at Alcalá. Hypolito asleep in an arm-chair. A clock strikes three. He awakes slowly.

Hyp. I must have been asleep! aye, sound asleep!

And it was all a dream. O sleep, sweet sleep!

Whatever form thou takest, thou art fair,

Holding unto our lips thy goblet filled

Out of Oblivion’s well, a healing draught!

The candles have burned low; it must be late.

Where can Victorian be? Like Fray Carillo,

The only place in which one cannot find him

Is his own cell. Here’s his guitar, that seldom

Feels the caresses of its master’s hand.

Open thy silent lips, sweet instrument!

And make dull midnight merry with a song.

(He plays and sings.)

Padre Francisco!

Padre Francisco!

What do you want of Padre Francisco?

Here is a pretty young maiden

Who wants to confess her sins!

Open the door and let her come in,

I will shrive her from every sin.

Enter Victorian.

Vic. Padre Hypolito! Padre Hypolito!

Hyp. What do you want of Padre Hypolito?

Vic. Come, shrive me straight; for if love be a sin

I am the greatest sinner that doth live.

I will confess the sweetest of all crimes,

A maiden wooed and won.

Hyp. The same old tale

Of the old woman in the chimney corner,

Who, while her pot boils, says—Come here my child;

I’ll tell thee a story of my wedding-day!

Vic. Nay, listen, for my heart is full; so full

That I must speak.

Hyp. Alas! that heart of thine

Is like a scene in the old play—the curtain

Rises to solemn music, and, lo! enter

The eleven thousand Virgins of Cologne!

Vic. Nay, like the Sibyl’s volumes, thou shouldst say;

Those that remained, after the six were burned,

Being held as precious as the nine together.

But listen to my tale. Dost thou remember

The gipsy girl we saw at Cordova

Dance the Romalis in the market-place?

Hyp. Thou meanest Preciosa.

Vic. Aye, the same.

Thou knowest how her image haunted me

Long after we returned to Alcalá.

Hyp. Thou even thought’st thyself in love with her.

Vic. I was; and, to be frank with thee, I am!

She’s in Madrid. O pardon me, my friend,

If I so long have kept this secret from thee;

But silence is the charm that guards such treasures,

And if a word be spoken ere the time,

They sink again, they were not meant for us.

Hyp. Alas! alas! I see thou art in love.

How speeds thy wooing? Is the maiden coy?

Write her a song, beginning with an Ave;

Sing as the monk sang to the Virgin Mary,

Ave! cujus calcem clarè

Nec centenni commendare

Sciret Seraph studio!

Vic. Pray do not jest! This is no time to jest!

I am in earnest!

Hyp. Seriously enamor’d?

What, ho! The Primus of great Alcalá

Enamor’d of a gipsy? Tell me frankly,

How meanest thou?

Vic. I mean it honestly.

The angels sang in heaven when she was born!

She is a precious jewel I have found

Among the filth and rubbish of the world.

I’ll stoop for it; but when I wear it here,

Set on my forehead like the morning star,

The world may wonder, but it will not laugh.

Hyp. If thou wear’st nothing else upon thy forehead

’Twill be indeed a wonder.

Vic. Out upon thee,

With thy unseasonable jests! Pray, tell me,

Is there no virtue in the world?

Hyp. Not much.

What, think’st thou, is she doing at this moment—

Now, while we speak of her?

Vic. She lies asleep,

And, from her parted lips, her gentle breath

Comes like the fragrance from the lips of flowers.

Her delicate limbs are still, and on her breast

The cross she pray’d to, e’er she fell asleep,

Rises and falls with the soft tide of dreams,

Like a light barge safe moor’d.

Hyp. Which means, in prose,

She’s sleeping with her mouth a little open!

Vic. O would I had the old magician’s glass

To see her as she lies in child-like sleep!

Hyp. And would’st thou venture?

Vic. Aye, indeed I would!

Hyp. Thou art courageous. Hast thou e’er reflected

How much lies hidden in that one word now?

Vic. Yes; all the awful mystery of Life!

I oft have thought, my dear Hypolito,

That could we, by some spell of magic, change

The world and its inhabitants to stone,

In the same attitudes they now are in,

What fearful glances downward might we cast

Into the hollow chasms of human life!

What groups should we behold about the death-bed,

Putting to shame the group of Niobe!

What joyful welcomes, and what sad farewells!

What stony tears in those congealed eyes!

What visible joy or anguish in those cheeks!

What bridal pomps, and what funereal shows!

What foes, like gladiators, fierce and struggling!

What lovers with their marble lips together!

Hyp. Aye, there it is! and if I were in love

That is the very point I most should dread.

This magic glass, these magic spells of thine

Might tell a tale ’twere better leave untold.

For instance, they might show us thy fair cousin,

The Lady Violante, bathed in tears

Of love and anger, like the maid of Colchis,

Whom thou, another faithless Argonaut,

Having won that golden fleece, a woman’s love,

Desertest for this Glaucè.

Vic. Hold thy peace!

She cares not for me. She may wed another,

Or go into a convent, and thus dying,

Marry Achilles in the Elysian Fields.

Hyp. (rising.) And so, good night! Good morning, I should say.

It is no longer night, nor is it day.

But in the east the paramour of Morn,

Infirm and old, lifts up his hoary head,

And hears the crickets chirp to mimic him.

And so, once more, good night! We’ll speak more largely

Of Preciosa when we meet again.

Get thee to bed, and the magician, Sleep,

Shall show her to thee, in his magic glass,

In all her loveliness. Good night! [Exit.

Vic. Good night!

But not to bed; for I must read awhile.

(Throws himself into the arm-chair which Hypolito has left, and lays a large book open upon his knees.)

Must read, or sit in reverie and watch

The changing color of the waves that break

Upon the idle seashore of the mind!

Visions of Fame! that once did visit me,

Making night glorious with your smile, where are ye?

O, who shall give me, now that ye are gone,

Juices of those immortal plants that blow

Upon Olympus, making us immortal!

Or teach me where that wondrous mandrake grows

Whose magic root, torn from the earth with groans,

At midnight hour, can scare the fiends away,

And make the mind prolific in its fancies?

I have the wish, but want the will to act!

Souls of great men departed! Ye whose words

Have come to light from the swift river of Time,

Like Roman swords found in the Tagus’ bed,

Where is the strength to wield the arms ye bore?

From the barred visor of antiquity

Reflected shines the eternal light of Truth

As from a mirror! All the means of action—

The shapeless masses—the materials—

Lie every where about us. What we need

Is the celestial fire to change the flint

Into transparent crystal, bright and clear.

That fire is Genius! The rude peasant sits

At evening in his smoky cot, and draws

With charcoal uncouth figures on the wall.

The man of genius comes, foot-sore with travel,

And begs a shelter from the inclement night.

He takes the charcoal from the peasant’s hand,

And by the magic of his touch at once

Transfigured, all its hidden virtues shine,

And in the eyes of the astonish’d clown

It gleams a diamond! Even thus transform’d,

Rude popular traditions and old tales

Shine as immortal poems, at the touch

Of some poor houseless, homeless, wandering bard,

Who had but a night’s lodging for his pains.

O there are brighter dreams than those of Fame,

Which are the dreams of Love! Out of the heart

Rises the bright ideal of these dreams,

As from some woodland fount a spirit rises

And sinks again into its silent deeps,

Ere the enamor’d knight can touch her robe!

’Tis this ideal that the soul of man,

Like the enamor’d knight beside the fountain,

Waits for upon the margin of Life’s stream;

Waits to behold her rise from the dark waters,

Clad in a mortal shape! Alas! how many

Must wait in vain. The stream flows evermore,

But from its silent deeps no spirit rises!

Yet I, born under a propitious star,

Have found the bright ideal of my dreams.

Yes! she is ever with me. I can feel,

Here, as I sit at midnight and alone,

Her gentle breathing! on my breast can feel

The pressure of her head! God’s benison

Rest ever on it! Close those beauteous eyes,

Sweet Sleep! and all the flowers that bloom at night

With balmy lips breathe in her ears my name.

(Gradually sinks asleep.)

END OF THE FIRST ACT.

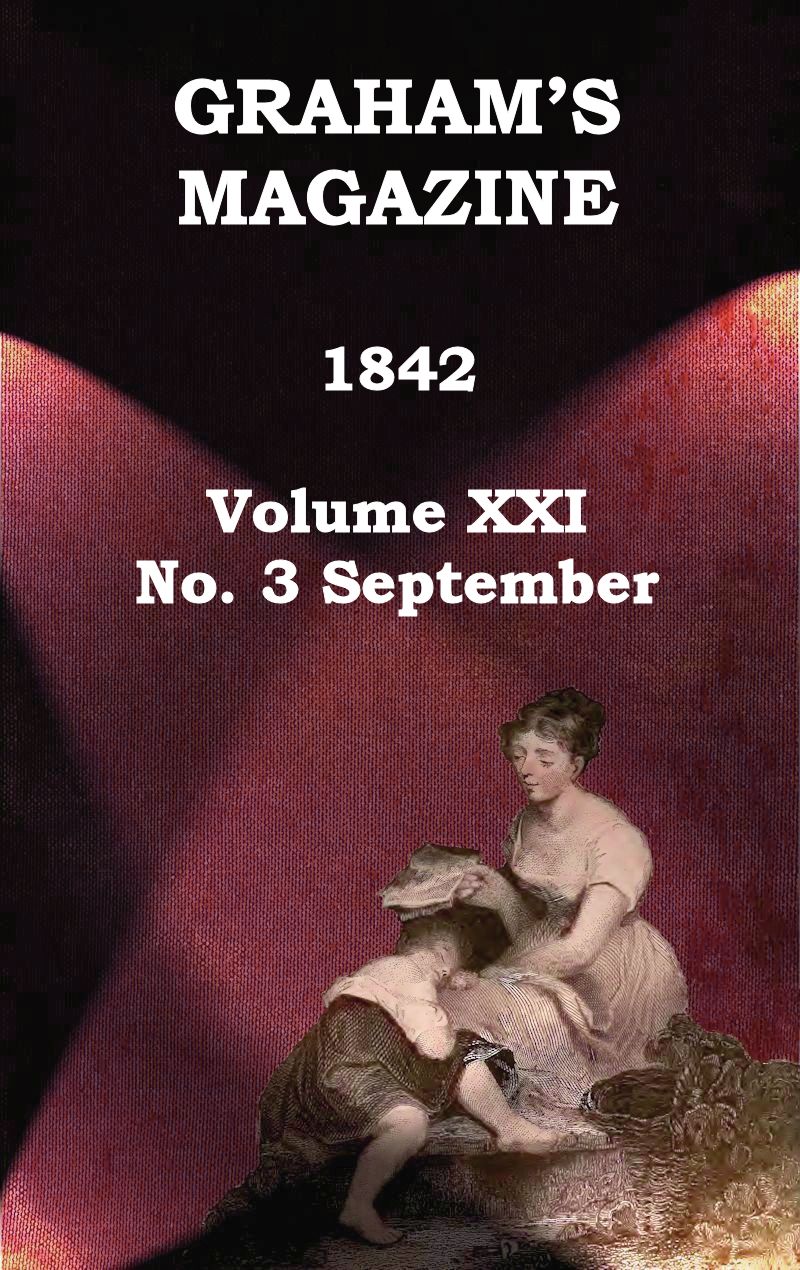

Drawn by E. Corbould. Engraved by Alfred Jones.

———

BY J. H. DANA.

———

In one of those stately old gardens which were attached to every lordly mansion of the reign of Charles the First, sat a cavalier and lady. The seat they occupied was a rude garden sofa, overshadowed by trees, and in close proximity to a colossal urn on which was represented in bold relief, according to the classic predilection of the age, Diana and her nymphs engaged in the chase. The lady was one of rare beauty. Indeed few creatures more lovely than Isabel Mordaunt ever graced a festive hall, or brushed the dew from the morning grass. She was gay, witty, eighteen, and an heiress. Her mother died when Isabel was an infant, and thus left chiefly to her own control she had grown up as wilful as a mountain chamois. Exulting in the consciousness of talent, there were few who had not experienced her wit. Yet she had a kind heart, and, if she was at times too apt to give offence, no one was more ready to atone for a fault. Her beauty and expectations had already drawn around her crowds of suitors; but though she laughed and chatted with all, she suffered none to aspire to an interest in her heart. Indeed she professed to be a skeptic to the reality of love. But, as is ever the case, her gay raillery and careless indifference seemed only to increase the number of her suitors.

The cavalier by her side was in the first flush of manhood, and one whose personal appearance rendered him a prize which any fair girl might be proud to win. Grahame Vaux had been the ward of Isabel’s father, and was but four years her senior. In childhood they had played together, and though subsequently separated by the departure of Vaux to the university, they had been again thrown into each other’s society at that critical period of life when the heart is most keenly alive to the influences of love. To Grahame this daily companionship was peculiarly dangerous. Isabel was just the being to dazzle a romantic character like his; for he regarded the sex with all the high, chivalrous feelings which actuated the Paladins of old, whom indeed he resembled in other respects. A second Sir Philip Sidney, he excelled in every graceful accomplishment. At Oxford he had won the first prize. In every manly sport he was pre-eminent. We will not trace the progress of his passion—how it sprung from a single word, fed on smiles, and finally devoured, as it were, his very being. Suffice it to say, he soon came to love Isabel with all the ardor of a first affection, worshiping her as an idolator adores his divinity, and evincing his passion in every look, word and gesture.

Perhaps this was not the surest road to the affections of a wilful creature like Isabel—perhaps the alternation of doubt and fear, of admiration and indifference, would more effectually have enlisted her feelings; but be this as it may, her new lover met at her hands the same capricious treatment which her other suitors received. In Grahame’s case this wilfulness was more than usually apparent, though there were not wanting those who said that this demeanor was only a veil worn to hide a growing preference for her noble-hearted lover. At any rate her conduct toward him was caprice itself. Now she would smile on him so sweetly that he could not help but hope, and now a word or gesture would plunge him into the deepest despair.

“I can endure it no longer,” at length he said, “I love Isabel!—Oh! how deeply and fervently God only knows. I will terminate my suspense. I will learn my fate. Better know the worst than live on in this agony.”

He rose and sought out the lady. She was at her favorite seat in the garden; and as she perceived him approaching, her color deepened, as if she divined, in Grahame’s excited air, the purpose of his visit. With that instinctive desire, so natural to the sex, to avoid the subject, she herself opened the conversation in a gay and trifling tone. Grahame, who could have stood the shock of battle undaunted, felt his heart fail him when he saw her sportive mood, but, firm in his resolve, he said, at length, at a suitable pause,

“Do you believe in love, Isabel?”

“Love! I believe in love!” laughingly replied the capricious girl. “What! give up my maiden liberty for a pretty gallant,—oh! no, Sir Romance, madcap as I am, it has not come to that. Believe in love, forsooth! why I should sooner believe that men were wise or women fickle. Love may sound very well in a play, but I’ll have none of it. Pale cheeks, sighs, and the gilded fetters of a wife are not for a free maiden who, like the untamed hawk, would soar whither she lists. Love, indeed!” and she laughed merrily.

Poor Grahame! how his sensitive heart throbbed at these words. He would have given worlds to be miles away. But the light, half-mocking laugh, all silvery though it was, with which she concluded, wrung even from him a reproach.

“Oh! Isabel,” he said, and his low voice trembled with emotion, “can you believe all this? Ah! little indeed then do you know of love.”

“And who would presume to think that I did know ought of it?” said Isabel, with a heightened color, and a flashing eye,—“I have no taste for jealous lovers or domineering lords; and I never saw one of your sex—I pray your pardon, fair sir—” and there was a slight scorn in her words, “who could tempt maiden to think twice of matrimony. Love indeed, forsooth! I pray Heaven to open men’s eyes to their vanity.”

The moment she had ceased speaking, Isabel would have given any thing to recall her words. Hurried away by her love of raillery, and a little piqued at the tone of reproach in which Grahame ventured, she had given free license to her speech, and said things which she well knew she did not believe. Her lover turned deadly pale at her words. Believing now that she had all along been trifling with his feelings, he started to his feet, and looking at her a moment sadly, exclaimed bitterly, “Isabel! Isabel! May God forgive you for this; I leave you and forever;” and ere she could reply, or Grahame see the tears that gushed into her eye, he darted through the neighboring shrubbery and was lost to sight. Isabel looked after, and called faintly to him to return, but if he heard her, which was scarcely possible, he heeded it not. Pride prevented her from repeating the summons; she saw him no more.

——

More than an hour elapsed before Isabel returned to the mansion, and when she did the traces of tears were on her cheeks. She instantly sought her chamber.

“He said we parted forever—oh! surely he cannot have meant it,” she exclaimed, “he will be here to-morrow. And then—” and she paused, while a blush mantled over her cheeks, and invaded even her pearly bosom.

But to-morrow came without Grahame. All through the long day Isabel watched for his arrival, and even ventured half way to the park-gates, but when she heard footsteps in the avenue ahead, she hurried trembling behind the shrubbery until she saw that the stranger was not her lover. And when night came, and still he did not appear, her heart was agitated by contending emotions; and while one moment pride would obtain the mastery, love would in turn subdue her bosom. Until this hour Isabel had never known how deeply she loved Grahame; for her passion, growing with her growth and increasing with her years, had obtained the mastery of her heart with such subtle and gradual power, that the rude shock of Grahame’s departure first woke her to a consciousness of her affection. And now she felt that she had wronged a true and noble heart. Had her lover then returned he would have won a ready confession of her passion; but day after day passed without his arrival, and finally intelligence was received that he had joined the army of King Charles, then first rallying around that ill-fated monarch, preparatory to the fatal civil war in which so many gallant cavaliers lost life and fortune. The news filled Isabel’s heart with the keenest anguish. “Alas! Grahame,” she said, as if in adjuration, “I love only you, and your noble heart deems I despise the offering. Could you but know the truth! But surely,” she continued, “he might have sought some explanation. Oh! if he had returned only for a moment, and given me the opportunity to ask forgiveness, he would not have had to complain of a cold and ungrateful heart in Isabel Mordaunt. He is unjust,” and thus resolving, she determined to demean herself with becoming pride.

However much, therefore, Isabel might suffer in secret, no curious eye was allowed to penetrate the recesses of her heart. To the world she appeared gay and witty as ever, and if sometimes the name of Grahame was mentioned, or his gallant deeds commended, she heard the announcement without betraying aught more than would have been natural in a common friend. She was often put to this trial, for, from the moment when Grahame joined the royal standard, his career had witnessed a succession of the most brilliant exploits. Seeming to be utterly regardless of life, he ventured deeds from which even the bravest had shrunk back. Wherever the storm of battle was thickest, wherever a post of extreme peril was to be maintained, there was Grahame, pressing forward in the front rank, like another Rinaldo. He did not shun the companionship of the gayer gallants of the camp, but he ever wore, amid their mirth, an expression of settled sadness. But this peculiarity was forgotten in the brilliancy of his exploits, and his name came at length to be so famous that when any new and daring deed was done, men asked at once whether Sir Grahame Vaux had not been there.

Isabel heard all this with a beating heart, but an unmoved cheek. She had schooled herself to disguise her heart, and she succeeded so that no one suspected the truth. Only her father, when he saw her refuse one after another of her many suitors, divined that some unrevealed secret lay hidden in her bosom, and remembering the sudden departure of Grahame, was at no loss to refer her conduct to the right cause. Meantime a change had gradually come over Isabel. She was less light-hearted than of old—her laugh, though musical, was scarcely as gay as it once had been—and her sportive wit no longer flashed incessantly like the lightning in the summer cloud.

The tide of war had long rolled steadfastly against the cavaliers, and finally the battle of Marston Moor closed the tragedy. The day after the news of the defeat arrived, a travel-soiled retainer of Grahame reached Mordaunt Hall and recounted in detail the events of that bloody field, from which he was a fugitive. He said that his master, when the day was lost, flung a discharged pistol into the thickest ranks of the enemy and died, like a knight of old, fighting to regain it. At these words her father turned to Isabel, in whose presence the retainer had related his story, and saw a deathly paleness overspread her cheek. The next instant she sank to the floor in a swoon.

“My child, my darling Isabel, speak,” said the aged father, raising her in his trembling arms. “Oh! I have long suspected this, and the blow has killed her! Why did I suffer her to hear this tale!”

With difficulty they revived her; but she only woke to a spell of sickness; and for weeks her fate hung in a balance between life and death.

——

But Grahame had not fallen. True, as his retainer asserted, he had maintained the unequal combat long after every one else had left the field, and true also he had finally been overwhelmed by numbers and left for dead, covered with wounds, upon the battle plain; but when the pursuing squadrons had swept by, leaving the field comparatively deserted, and the chill night wind breathed with reviving coolness over his brow, he awoke to consciousness, and was enabled, by the assistance of one of his followers who yet prowled about the scene of carnage in the hope of finding his master, to gain a secure retreat where he might be cured of his wounds. Here, on the rude couch of a humble cottage, he lay for weeks, and the third month had set in after the battle, before he was enabled to leave his lowly shelter. During all this time his faithful retainer watched over him, tending him one while with the assiduity of a nurse, and another while, on any alarm, preparing to defend him to the last extremity.

“I am now a houseless, persecuted outlaw,” said Grahame when he mounted his steed to leave the humble cottage where he had found shelter. “The crop-eared puritanic knaves have shed the best blood in the country and they will not spare mine. The land is overrun with their troops, and there is no safety, in this portion of it at least. I will go once more to the halls of my fathers, take a last farewell of them, and then carry my life and sword to some foreign market, for, God help me, there is nothing else left to do.”

It was a bright sunny afternoon when Grahame reached his ancestral halls, now deserted and melancholy. Already had the minions of the parliament sequestrated and shut up the mansion, and it was only through the fidelity of an old servant, who yet lingered around the place, that its former master was enabled to enter its portals. The aged retainer wept with joy on his lord’s hand, and said,

“Oh! dark was the day when news came of your honor’s death.”

“And was it then reported that I was no more? Yet how can I wonder at it, considering my long seclusion.”

“Oh! yes—and sad times too they had of it over at Mordaunt Hall. The young mistress fainted away, and was near dying, though since she has heard that you yet lived—as we all did, you know, by your messenger,—she has wonderfully revived. But what ails you, my dear master?—are you sick?”

“No—no—but I must to horse at once,” said Grahame, whose face had turned deadly pale at his servant’s joyful intelligence. “I may be back to sleep here—think you I can have safe hiding for one night in my father’s house?”

“That may you, God bless your honor,” said the old man as Grahame rode away.

“She loves me, then! Life is no more all a blank,” said the young knight almost gaily, as he dashed through the arcades of his park, his steed seeming to partake in his master’s exhilaration.

Isabel sat in the great parlor of Mordaunt Hall, looking down the broad avenue that led to the park gates. A partial bloom had been restored to her cheek, for hope whispered to her that Grahame might yet be hers. Suddenly a figure emerged to sight far down the avenue, and though years had elapsed since she had seen that form, and though she imagined her lover to be far away, and perhaps in exile, her heart told her at once that the approaching figure was Grahame’s. For a moment her agitation was so excessive that she thought she would have fainted, but though there were many painful recollections, her sensations on the whole were of a happy kind. Quick as lightning, the thought flashed across her mind that Grahame had heard of her agitation when the false report of his death had reached Mordaunt Hall, and, for the moment, maidenly shame overcame every other feeling in her bosom. Conscious that she dare not meet her lover without preparation, she took to instant flight, and sought, as if instinctively, her favorite seat in the garden. Here, resting her head on her hands, she strove to collect her thoughts. It was not long before she heard a tread on the graveled walk, and her whole frame trembled with the consciousness that the intruder was Grahame. Nervous, abashed, unable to look up, her heart fluttered wildly against her boddice. How different was she from the gay, capricious creature who had occupied that same seat, two short years before. She heard the footstep at hand, and her agitation increased. She knew that her lover had taken his seat beside her, and yet she dared not let her eye meet his, but blushing and confused she offered no resistance when he took her trembling hand in his.

“Isabel—dear Isabel!” said a manly voice, and though the tones were full of emotion, the accents were clear and firm, for it was not Grahame now who trembled, “let us forget the past,” and he stole his arm around her waist. “We love each other—do we not, dear Isabel?”

Isabel raised her eyes, now beaming with subdued tenderness, to her lover’s face, and then bursting into tears was drawn to his bosom, as tenderly as a mother may press her new-born infant to her heart.

The interest of Isabel’s father, who had taken no part in the civil war, procured for Grahame an immunity from proscription; and when his estates were brought to the hammer, under the order of the parliament, they were purchased by Mr. Mordaunt, and restored to their rightful owner. Long and happily together lived Sir Grahame Vaux and his beautiful wife, and when Charles the Second was restored to his kingdom, none welcomed him back with more joy than the now blooming matron, and her still noble looking lord.

———

BY THE AUTHOR OF “CRUISING IN THE LAST WAR,” THE “REEFER OF ’76,” ETC.

———

The ten minutes that elapsed before I reached the door of the Hall seemed to be protracted to an age, and were spent in an agony of mind no pen can describe. Oh! to be thus deceived—to part from Annette as we had parted—to think of her by day and dream of her by night—to look forward to our meeting with a thrill of hope, and strive to win renown that I might shed a lustre around my bride—and then, after all my toils, and hopes, and struggles, to come back and find her wedded—God of heaven! it was too much. But, notwithstanding my agony, my pride revolted at the display of any outward emotion. I would not for worlds that Annette should know the torture her faithlessness had inflicted on my bosom. No! I would smooth my brow, subdue my tongue, and control my every look. I would jest, smile, and be the gayest of the gay. I would wish Annette and her husband a long and happy life, and no one should suspect that, under my assumed composure, I wore a heart rankling with a wound that no time nor circumstance could cure. I resolved to see Annette, to play my part to the end, and then, returning to my post, to find an honorable death on the first deck we should surmount. My reflections, however, were cut short by the stoppage of the vehicle before the door of the mansion. A servant hastened to undo the coach steps, and, nerving myself for the interview that was at hand, I stepped out. The man’s face was strange to me, and I saw that it displayed some embarrassment.

“Will you announce me to Mr. St. Clair,” I said, “as Lieutenant Cavendish?”

“Mr. St. Clair, I regret to say,” replied the man politely, “is not at the Hall. The carriages have just driven off, and if they had not taken the back road through the park, would have met you in the avenue. Mr. St. Clair accompanies the bride and groom on a two weeks’ tour.”

My course was at once taken; and, as the criminal feels a lightening of the heart when reprieved, so I experienced a relief in escaping the trying experiment of mingling with the bridal party. Hastily re-ascending the carriage steps, I left my name with the servant, and ordering the coachman to drive off, left Pomfret Hall, with the resolution never again to return. At the village I paused a few minutes to indite a letter to Mr. St. Clair, in which I regretted my inopportune arrival, and wished a long life of happiness to him and to Annette. Then, re-entering the coach, I threw myself back on the seat, and, while I was being whirled away from Pomfret Hall, gave myself up to the most bitter reflections. As I now and then looked out of the window and recognized familiar objects along the road, I contrasted my present despondency with the hope that had thrilled my heart when I passed them a few hours before. Then, every pulse beat faster with delicious anticipations: now, I scarcely wished for more than an honorable death. At length my thoughts took a turn, and I reviewed the past, calling to mind every little word and act of Annette, from which I could draw either hope or despair.

“Fool that I was,” I exclaimed, “to think that the wealthy heiress could stoop to love a penniless officer. And yet,” I continued, “my fathers were as noble as hers, aye! and enjoyed wealth and honors to which the St. Clairs never aspired.” But again a revulsion came across my feelings, and I said, “Oh! Annette, Annette, could you but know my misery, you might have paused. But God grant you may find a heart as true to you as mine.” Thus harassed by contending emotions, now giving way to my love, and now yielding to indignation and pride, I spent the day, and when at night, preparatory to retiring, I happened to cast a look into the mirror, I started back at my haggard appearance. But there are moments of agony which do the work of years.

My messmates, one and all, were astonished at my speedy return, but luckily it had been determined to put to sea at once, so that if I had remained at Pomfret Hall until the expiration of my leave of absence I should have lost the cruise. One or two of my companions, who prided themselves on their superior intelligence, gave me the credit of having, by some unknown means, heard of the change in our day of sailing, and so hastened my return to my post. They little dreamed of the true cause, for to them, as to all others, I wore the same mask of assumed gaiety.

We sailed in company with The Arrow, but, ere we had been out a week, were separated from our consort. Our orders were, in such an emergency, to make the best of our way southward, and rendezvous at St. Domingo.

I had turned in one night, after having kept watch on deck until midnight, when, in the midst of a refreshing sleep, I was suddenly awoke by a hand laid on my shoulder, at the same time that a voice said—

“Hist! Cavendish; don’t talk in your sleep.”

I started to my feet, but, for a moment, my faculties were in such a whirl that the dream in which I had been reveling, mingling with the scene before my waking senses, confused and bewildered me so that I knew not what I uttered.

“St. Clair! Pomfret Hall! why your wits are wool gathering, my dear fellow,” said the doctor—for I now recognised my old friend—“of what have you been dreaming? You look as if you thought me a spectre sent to call you from Paradise.”

I had indeed been dreaming. I fancied I was far away, wandering amid the leafy shades of Pomfret Hall with Annette leaning on my arm, and ever and anon gazing up into my face with looks of unutterable love. I heard the rustle of the leaves, the jocund song of the birds, and the soothing sound of the woodland waterfall, but sweeter, aye! a thousand times sweeter than all these, came to my ears the low whisper of my affianced bride. Was I not happy? And we sat down on a verdant bank, and, with her hand clasped in mine, and her fair head resting on my bosom, we talked of the happiness which was in store for us, and projected a thousand plans for the future. From visions like this I awoke to the consciousness that Annette was lost to me forever, and that even now the smiles and caresses of which I had dreamed were being bestowed upon another. A pang of keenest agony, a sharp, sudden pang, as if an icebolt had shot through my heart, almost deprived me for a moment of utterance, and I was fain to lean against a timber for support. But this weakness was only momentary, for, rallying every energy, I conquered my feelings, though not so soon but that the doctor saw my emotion.

“Are you sick, my dear fellow?” he said anxiously. “No! well, you do look better now. But I came to inform you that as rake-helly a looking craft as ever you saw is dogging us to windward, and the Lord only knows whether we wont all be prisoners, and mayhap dead men, before night.”

I hurried on my clothes, and, following him to the deck, saw, at the first glance, that the good doctor’s fears respecting the strange sail were not without foundation. She was a sharp, low brig, with masts raking far aft, and a spread of canvass towering from her decks sufficient to have driven a sloop of war. The haze of the morning had concealed her from sight until within the last five minutes; but now the broad disc of the sun, rising majestically behind her, brought out her masts, tracery and hull in bold and distinct relief. When first discovered, she was within long cannon shot, but standing off to windward. She altered her course immediately, however, on perceiving us, and was already closing. She carried no ensign, but there was that in her crowded decks and jaunty air which did not permit me to doubt a moment as to her character.

“A rover, by ——,” said the skipper, who had been scrutinizing the strange sail through a glass; “and she is treble our force,” he continued, in a whisper to me. “We have no choice, either, but to fight.”

I shook my head, for it was evident that escape was impossible.

“She sails like a witch, too,” I replied, in the same low tone, “and would overhaul us, no matter what her position might be.”

“I wish we were a dozen leagues away,” said the captain, shrugging his shoulders, “there is little honor and no profit in fighting these cut-throats, and if we are whipt, as we shall be, they will slit our windpipes as if we were so many sheep in a slaughter-house. Bah!”

“Not so,” I exclaimed enthusiastically, “we will die sword in hand. Since these murderers have crossed our path we must, if every thing else fail, suffer them to board us, and then blow the schooner out of water. I myself will fire the train.”

“Now, by the God above us, you speak as a brave man should, and shame my momentary disgust, for fear I will not call it. No, Jack Merrivale never wanted courage, however prudence might have been lacking. But little did I think that you, Cavendish, would ever show less prudence than myself, as you have to-day. You seem a changed man.”

“I am one,” I exclaimed; “but that is neither here nor there. When once yon freebooter gets alongside, Harry Cavendish will not be behindhand in doing his duty.”

My superior, at any other time, could not have failed to notice the excitement under which I spoke, but now his mind was too fully occupied to give my demeanor a second thought, and our conversation was cut short by a ball from the pirate, which, whistling over our heads, plumped into the sea some fathoms distant. At the same instant a mass of dark bunting shot up to the gaff of the brig, and, slowly unrolling, blew out steadily in the breeze, disclosing a black flag, unrelieved by a single emblem. But we well knew the meaning of that ominous ensign.

“He taunts us with his accursed flag,” said the skipper energetically; “by the Lord that liveth, he shall feel that freemen know how to defend their lives and honor. Call aft the men, and then to quarters. We will blow yon scoundrels out of water, or die on the last plank.”

Never did I listen to more vehement, more soul-stirring eloquence than that which rolled, like a tide of fire, from the captain’s lips when the men had gathered aft. Every eye flashed with indignation, every bosom heaved with high and noble daring, as he pointed impetuously to the foe and asked if there was one who heard him that wished to shrink from the contest. To his impassioned appeal they answered with a loud huzza, brandishing their cutlasses above their heads and swearing to stand by him to the last.

“I know it, my brave boys—I remember how you fought the privateer’s men,” for most of his old crew had re-entered, “but yonder cut-throats are still more deceitful and blood-thirsty. We have nothing to hope for from them but a short shrift and the yard-arm. We fight, not for our country and property alone, but for our lives also. The little Falcon has struck down too many prizes already, to show the coward’s feather now. Let us make these decks slippery with our best blood rather than surrender. Stand by me, if they board us, and—my word on it—the survivors will long talk of this glorious day. And now, my brave lads, splice the main-brace, and then to quarters.”

Another cheer followed the close of this harangue, when the men gathered at their quarters, each one as he passed to his station receiving a glass of grog. As I ran my eye along the decks, and saw the stalwart frames and flashing eyes of the crew, I felt assured that the day was destined to be desperately contested; and when I thought of the vast odds against which we had to contend, and the glorious deeds which this superiority would make room for, I experienced an exultation which I cannot describe. The time for which, in the bitterness of my heart, I had prayed, was come; and I resolved to dare things this day which, if they ever reached the ears of Annette, should prove to her that I died the death of a gallant soldier. The thought that, perhaps, she might regret me when I was gone, was sweeter to me than the song of many waters.

Little time, however, was left for such emotions, for scarcely had the men taken their stations when the pirate, who had hitherto been manœuvering for a favorable position and only occasionally firing a shot, opened his batteries on us, discharging his guns in such quick succession that his sides seemed one continuous blaze, and his tall masts were to be seen reeling backwards from the shock of his broadside. Instantaneously the iron tempest came hurtling across us, and for a space I was bewildered by the rending of timbers, the falling of spars, and the agonizing shrieks of the wounded. The main-top-mast came rattling to the deck with all its hamper at the very moment that a messmate fell dead beside me. For a few minutes all was consternation and confusion. So rapid had been the discharges, and so well aimed had been each shot, that, in the twinkling of an eye, we saw ourselves almost a wreck on the water, and comparatively at the mercy of our foe.

“Clear away this hamper,” shouted the skipper, “stand to your guns forward there, and give it to the pirate.”

With the word the two light pieces and the gun amidships opened on the now rapidly closing foe; but the metal of all except the swivel was so light that it did no perceptible damage on the thick-ribbed hull of our antagonist. The ball from the long eighteen, however, swept the decks of the foe, and appeared to have carried no little havoc in its course. But the broadside did not check the approach of the rover. His object was manifestly to run us afoul and board us. Steadily, therefore, he maintained his course, swerving scarcely a hair’s breadth at our discharge, but keeping right on as if scorning our futile efforts to check his progress. We did not, however, intermit our exertions. Although crippled we were not disheartened—despairing, we entertained no thought of submission, but rallying around our guns, we fought them like lions at bay, firing with such rapidity that our decks, and the ocean around, soon came to be almost obscured in the thick fleecy veil of smoke that settled slowly on the water. Every few minutes a ball from the pirate whizzed by in our immediate vicinity, or crashed among our spars; but the increasing clouds of vapor, clinging about the pathway of our foe as well as of ourselves, made his fire naturally less deadly than at first. For a short space we even lost sight of our antagonist, and the gunners paused, uncertain where to fire; but suddenly the lofty spars of the pirate were seen riding above the white fog, scarcely a pistol shot from us, and in another minute, with a deafening crash, the rover ran us aboard, his bowsprit jamming in our fore-rigging as he approached us head on. Almost before we could recover from our surprise we heard a stern voice crying out in the Spanish tongue for boarders, and immediately a dark mass of ruffians gathered, like a cluster of bees, on the bowsprit of the foe, with cutlasses brandished aloft, preparatory to a descent on our decks.

“Rally to repel boarders!” thundered the skipper, springing forward, “ho! beat back the bloodhounds from your decks,” and with the word, he made a blow at a desperado who, at that moment, sprang into the fore-rigging; when my superior drew back his sword it was red with the heart’s blood of the assailant, who, falling heavily backwards with a dull plash, squatted a second on the water, like a wounded water-fowl, and then sank forever. For a single breath his companions stood appalled, and then, with a savage yell, leaping on our decks, fiercely attacked our little band. In vain our gallant tars disputed every inch of ground—in vain one after another of the assailants dyed the deck with his blood—in vain by word and deed the skipper incited the crew to almost gigantic exertions; nothing could resist the overpowering tide of assailants which poured on in an unremitting stream from the brig, bearing down every thing before it as an avalanche from the hills. Step by step our brave lads were steadily forced backwards, until at length the whole forecastle was in possession of the foe, and a solid mass of freebooters was advancing on the starboard side of the open main-hatch, in eager pursuit of the retreating crew. I had foreseen this result to the conflict, and instead, therefore, of aiding to repel the boarders, had been engaged in loading one of the lighter guns with grape, and dragging it around, so as to command this very path;—a duty which I had been enabled to perform unnoticed by either party in the fierce excitement of the mêlée. I had hardly masked my little battery, and not three minutes had elapsed from the first onset of the boarders, when my messmates came driving towards me, as I have described, beaten in by the solid masses of the enemy. Already the fugitives had passed the hatchway, and the foremost desperados of the assailing column were even now within three feet of the muzzle of my gun, when I signed to my confederate to jerk off the tarpaulin which had masked our piece. The pirates started back in horror when they saw their peril, but I gave them no time to escape. Quick as lightning I applied the match, and the whole fiery cataract was belched upon them. Language cannot depict the fearful havoc of that discharge. The hurricane of fire and shot mowed its way lengthwise, through the narrow and crowded column, scattering the dying and the dead beneath its track, as a whirlwind uproots the forest trees; while groans, and imprecations, and shrieks of anguish rent the air, drowning the sounds of the explosion, and the crashing of the grape, amongst its victims.

“Now charge!” I shouted, as if seized with a sudden frenzy, springing into the very midst of the foe, “charge them, my gallant braves, and sweep the murderers from the deck. No quarter to the knaves! Hew them to the brisket,” and following every word with a blow, and seconded by our men who seemed to catch my fury, we made such havoc among those of the pirates whom the grape had spared, that, astonished, paralized, disconcerted, and finally struck with mortal fear, they fled wildly from the schooner, some regaining their craft by the bowsprit, some plunging overboard and swimming to her, and some leaping headlong into the deep never to rise again. Seizing an axe, and springing forward, I hastily cut our hamper loose from the foe, and with the next swell the two vessels slowly parted.

“Now to your guns, my men,” shouted the skipper, unconscious of a dangerous wound, in the excitement of the moment, “give it to them before they can rally to their quarters. Fire!”

We poured in our broadsides like hail, riddling even the solid sides of our foe, and making his decks slippery with blood, and all this before the discomfited freebooters could rally to their guns and return our shots. Our men, fired with an enthusiasm which approached to madness, loaded with a speed that seems to me now incredible, and the third broadside was shaking every timber of our little craft, before a solitary gun was discharged in reply from the pirate.

“Ah! he has woke up at last,” said my old friend, the captain of our long Tom, “and she may yet regain the day if we don’t fight like devils. Bring me that shot from the galley.”

“In God’s name, what do you mean?” said I, as he coolly sat down by his piece. “In with the ball and let the rover have it—not a moment is to be lost.”

“Aye! I knows that, leftenant; and here comes the settler for which I waited,” he exclaimed, as the cook brought a red-hot shot from the galley, “I thought I’d venture on a little experiment of my own, and I’ve seen ’em do wonders with these fiery comets afore now. There—there she has it,” he exclaimed, as the shot was sent home, “now God have mercy on them varmint’s souls.”

From some strange, unaccountable presentiment, I stepped mechanically backward and cast an eye at the brig, which had now floated to some distance. As I did so, a trail of fire glanced before my sight, and I saw the simmering shot enter her side. Thought was not quicker than the explosion which followed, shaking the sea beneath and the sky above, and almost deafening the ear with its unearthly concussion, while instantaneously a gush of flame shot far up into the sky; the masts of the vessel were lifted perpendicularly upwards, and the whole air was filled with shattered timbers and mangled human bodies that fell the next minute pattering around us into the deep. Oh God! the fearful sight! The shrieks of the wounded and drowning—the awful struggles of the poor wretches in the water—the sullen cloud that settled over the scene of death, will they ever pass away from my memory? But I drop a veil over a sight too horrible to recount. Suffice it to say, of all the rover’s crew, not one survived to see that sun go down. A few we picked up with our boats, but they died ere night. The cause of the explosion is soon told. The brig’s magazine had been struck and fired by our LAST SHOT.

———

BY G. FORRESTER BARSTOW.

———

Away! away! the bright blue waves are dashing

With sparkling crests like spotless mountain snow,

As in the fight our mighty falchion’s flashing

Above the foe.

Away! away! old ocean spreads before us

Its broad domain, where sunk the sun’s last ray,

While in the deep blue sky that arches o’er us

Stars shine to light our way.

Away! away! from home’s entrancing pleasures

The festal board, the bower of lady fair,

The roof that holds our hearts’ most valued treasures,

The loved ones there,

We go: and while the burning tear is starting

From eyes that gaze upon a shoreless main,

Fill! fill to those from whom we now are parting,

And ne’er may see again.

Fill to the loved ones whose bright eyes are beaming

As yonder stars in their pure heaven of blue,

Bright as the stars those brilliant eyes are gleaming

With heaven’s own hue.

Fill to the loved ones whose bright cheeks are glowing

As eastern heaven in morning’s virgin ray,

Whose necks, down which their auburn locks are flowing,

Would shame the dashing spray.

Away! away! above the waves careering,

Our ship speeds lightly on an unknown way,

Far to the west our course we now are steering

With spirits gay.

Far to the west, where brilliant gems are shining,

And mighty rivers roll o’er golden sands,

Where sweetest flowers and richest grapes are twining,

Wooing the stranger’s hands.

TO AMERICAN AUTHORS AND THE AMERICAN PRESS

IN BEHALF OF AN INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT.

Gentlemen:—You have the credit, at this moment, of ruling the world—at least your part of it; and cannot yet enact a single statute by which your share of worldly right and profit shall be secured to you. Walking, in the world’s eye, as strong and beautiful as angels, you cannot perform the day’s work, counted either in money or in bill-making influence, of a rude Missourian or a lean Atlantic citizen.

Aiding, as you do, by your inventive genius in all the great enterprises of the day—pushing forward every great and good undertaking to an issue of success—you lack the will or the skill to create a simple mill-contrivance by which your grain may be ground and bread furnished to your board.

You project, but do not realize. You sow, but do not reap. You sail to and fro—merchantmen and carriers to all the world of thought—the whole ocean over, but find no harbor and acquire no return. How much longer you will consent to keep the wheels of opinion in motion: to do the better part of the thinking and writing of these twenty-six States, without hire or fee, it rests with you to say. I merely put the case to you to see how it strikes you.

I address you in the mass, writers of books and framers of paragraphs together, because, at bottom, all who wield the pen have interests in common; and because I am anxious (I confess it) to have the whole force of the Press, whatever shape it takes, combined and consolidated against an injustice which could not live an hour if the Press knew its rights and its strength. The rights and the respectability of the one are, in the end, the rights and the respectability of the other; based in both cases on the worth and dignity of literary property.

No community is secure, it seems to me, where any law or fundamental right is systematically violated.

Either by instant vindication, through blood, and pillage, and massacre; or by the more silent and deadlier agency of the opposite wrong and a whole brood of fierce allies sprung from its loins, is this truth, at all times, asserted and made good. From the original wrong, lying in many cases close to the heart of society, there spreads a secret and invisible atmosphere of pestilence, in which all kindred rights moulder and decay, until their life at last goes out at a moment when no man had guessed at such a result. Neither statesmen nor people are, therefore, wise in tampering with a single principle: or in yielding a jot of the immutable truth to plausible emergency or the fair-seeming visage of an immediate good.

The law of property, in all its relations and aspects, is one of these primary anchors and fastenings of the social frame. And what evils, I am asked, have grown from the alleged neglect of literary property? I will mention one by way of illustration.

You are all of you aware, by this time, that the extensive printing and publishing establishment of Harper & Brothers, Cliff street, New York, was burned in the early part of June; and that a heavy loss accrued to them from the burning.

The fire was attributed, immediately after it occured, by the public prints to the hand of design. “It is supposed that one object of the incendiaries was to obtain copies of a new novel, by James, of which the Messrs. Harper had the exclusive possession.” Another paper enlarges this statement—“we see suspicions expressed that the object was to get possession of a new novel, ‘Morley Ernstein,’ which was in sheets, for cheap publication.” Here is a natural, logical sequence, and just such a one as might have been expected. If the conjecture should not prove a fact, it ought to be one, because this is just the period and the very order in which we might expect an incident of this kind to occur; perhaps not on quite so large a scale, nor with the necessary melo-dramatic admixture of fire. It might have been a plain burglary, prying a ware-house door open with a bar, for a copy; or, knocking a man over, at the edge of evening, and plucking the sheets from under his arm.

Piracy and burning are, perhaps, so nearly akin that, after all, they have wrought out the sequence more naturally than if it had been left to the friends of copyright to suggest to them in what order they should occur. In Elia’s legend, a building is burned that a famishing Chinaman may have roast pig; in the reality of the present fire a publisher’s warehouse was put in flames, not only to prevent a famishing author from having roast pig in presenti, but also, by a decisive blow, to further the good principle, that there should be no roast pig (nor even salt and a radish) for famishing authors in all future time. Let it not be said I press this point, a mere surmise, too far. Surmise as it is, it receives countenance and consistency from a previous fact, namely, that one of the large republishing newspapers was charged, not long since, by the other—and this was made a matter for the Sessions—with the felony of abstracting the sheets of an English work from the office of its rival. This—an invasion of property—is only one of the external evils growing out of a false and lawless state of things. Of others which strike deeper; which create confusion and error of opinion; which tend to unsettle the lines that divide nation from nation; to obliterate the traits and features which give us a characteristic individuality as a nation—there will be another and more becoming opportunity to speak.

As it is, by fair means or foul, the weekly newspaper press, with its broad sheet spread to the breeze, is making great head against the slow-sailing progress of such as trust to the more regular trade-winds for their speed. And this, fortunately (as error cannot long abide in itself,) is creating changes of opinion of infinite advantage to the great cause of international copyright.

A little while ago, we had the publishers petitioning and declaiming against an international copyright, (I forget what arguments they employed;) and, lo! their breath is scarcely spent when the ground slides from under them, and the whole publishing business—at least a considerable section of it—which they meant to uphold by false and hollow props, has tumbled into chaos, and an organic change has passed through the world of publication. Now they begin—and we are glad to have so powerful and so respectable a body convert to our side, on whatever terms—to see the matter in a new light; the affection for the people, and the cheap enlightenment of the people, and the people’s wives and children, which they made bold (out of an exceeding philanthropy) to proclaim in market-places and the lobbies of Congress, is wonderfully dwindled.

It isn’t a pleasant thing, after all, to have one’s printing-house and bindery burned to the ground, even for so laudable an object. Suppose we have the law: a little civilized recognition of the rights of authors (merely by way of clincher, however, to the absolute, primary and indefeasible rights of publishers) might be an agreeable change from this barbarous system of non-protection. The old plan, it must be admitted, has its disadvantages. Let’s have the law! And here you may suppose the hats of certain old, respected and enterprising publishers to rise into the air, in a sort of fervor or ecstasy, which it is entirely out of their power to control.

Is there or is there not a property in a book: a primitive, real, fundamental right in its ownership as in any estate or property? Often and clearly as this question has been determined, the opponents of a law, by stress of argument, are driven upon denying it over and over again, and making use of every sort of ridiculous and irrelevant illustration to crowd the right out of the way. They fly into all corners of creation in pursuit of an analogy, and come back without as much as a sparrow in their bag.

One of them, for example, says, “We buy a new foreign book; it is ours; we multiply copies and diffuse its advantages. We also buy a bushel of foreign wheat, before unknown to us; we cultivate, increase it, and spread its use over the country. Where is the difference? If one is stealing, the other is so. Nonsense! neither is stealing. They are both praiseworthy acts, beneficial to mankind, injurious to nobody, right and just in themselves, and commendable in the sight of God.” This reasoner, of a pious inclination and most excellent moral tendencies, has made but a single error—he thinks the type, stitching and paper are THE BOOK! He forgets that when you buy a book you do not buy the whole body of its thoughts in their entire breadth and construction, to be yours in fee simple for all uses, (if you did, the vender would be guilty of a fraud in selling more than a single copy of any one work;) but simply the usufruct of the book as a reader. Any processes of your own mind exerted upon that work, or parts of it, make the result, so far, your legitimate property, and is one of the incidents of your purchase. To reprint the work in any shape, as a complete, symmetrical composition, is a violation of the original contract between the vender and yourself; whether it be in folio or duodecimo, in the form of newspaper or pamphlet—there lies THE BOOK, unchanged by any action of your own mind. The wheat, of which you have purchased the bushel, in the mean time has been sown in your field, (there’s a difference to begin;) which has been prepared by your plough and plough-horse for its reception; the kindly dews and rains of heaven—which would answer to the genial inspirations and movements of the mind, in the other case—descend upon it; it is guarded by walls and hedges from inroad; the weeds and tares which would fain choke it are plucked out by a careful hand; at last it is reaped and gathered in by the harvestman to his garners. The one bushel has become a thousand; but it has passed through a thousand appropriating and fructifying processes to swell it to that extent. It has not been merely poured out of one bushel measure into another bushel measure. Though the one plough the earth, and the other plough the sea, the world will recognize a distinction, a delicate line of demarcation between farmer (man’s first occupation) and pirate (his last.) The republishers—the proprietors of the mammoth press—groan under the aspersion of piracy and pillage laid at their door: they complain of the harshness of epithet which denounces them as Kyds and MacGregors. They must bear in mind that authors and republishers are likely to regard this question from very different points of view: that the poor writer, regarding himself as plundered, defrauded of a positive right, and of a property as real and substantial as guineas, or dollars, or doubloons, may feel a soreness of which the other party, living as he does on the denial of that right, and the seizure of that property, without charge or cost, may not be quite as susceptible. Let us make an effort to bring this point home to these gentlemen in an obvious and intelligible illustration.