The Project Gutenberg eBook of The little country theater, by Alfred G. Arvold

Title: The little country theater

Author: Alfred G. Arvold

Release Date: July 12, 2022 [eBook #68514]

Language: English

Produced by: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE LITTLE COUNTRY THEATER

FOUNDED

FEBRUARY TENTH, NINETEEN HUNDRED

AND FOURTEEN, BY ALFRED G. ARVOLD

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

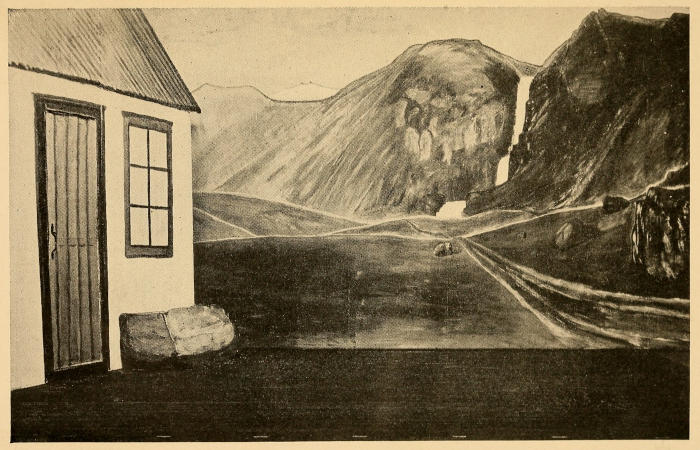

The Quaint Cottage, the Snow-White Capped Mountain, the Tumbling Waterfall Were Painted in a Manner Which Brought Many Favorable Comments

THE LITTLE COUNTRY THEATER

BY

ALFRED G. ARVOLD

NORTH DAKOTA AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE

Fargo, North Dakota

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1922

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Copyright, 1922

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

Set up and electrotyped. Published November, 1922

TO MY MOTHER

WHOSE VISION CAUSED ME

TO SEE BIG THINGS

“The theater is a crucible of civilization. It is a place of human communion. It is in the theater that the public soul is formed.”

Victor Hugo.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | The Raindrops | 1 |

| II. | Country Folks | 17 |

| III. | The Land of the Dacotahs | 33 |

| IV. | The Little Country Theater | 41 |

| V. | The Heart of a Prairie | 59 |

| VI. | Characteristic Incidents | 67 |

| VII. | A Bee in a Drone’s Hive | 95 |

| VIII. | Larimore | 153 |

| IX. | Forty Towns | 167 |

| X. | Cold Spring Hollow | 179 |

| Appendices | 187 |

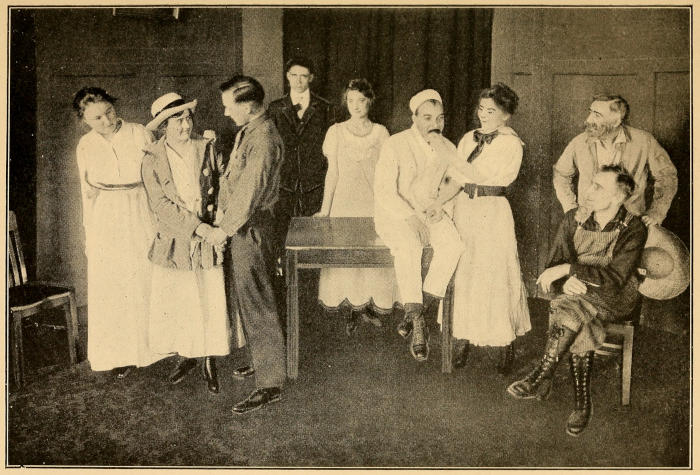

| Scene—“The Raindrops” | Frontispiece |

| Facing Page | |

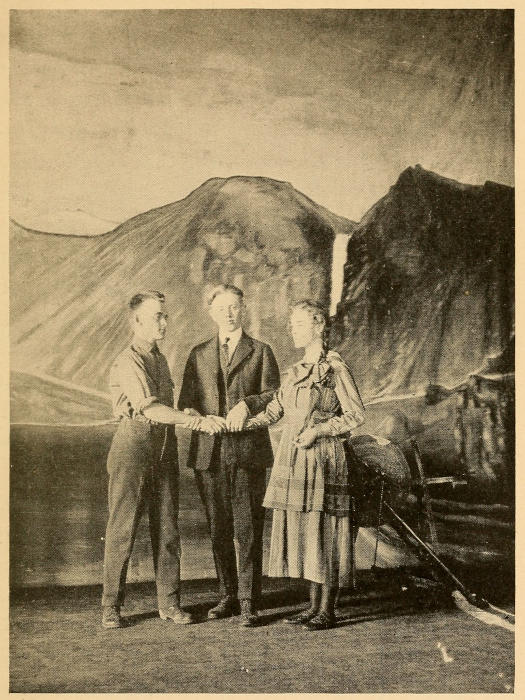

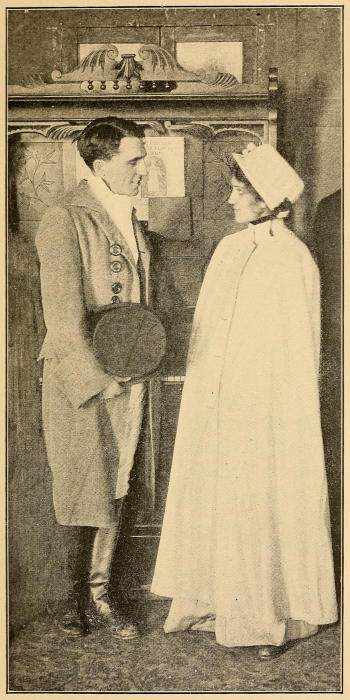

| “Perhaps we will meet again like the raindrops” | 4 |

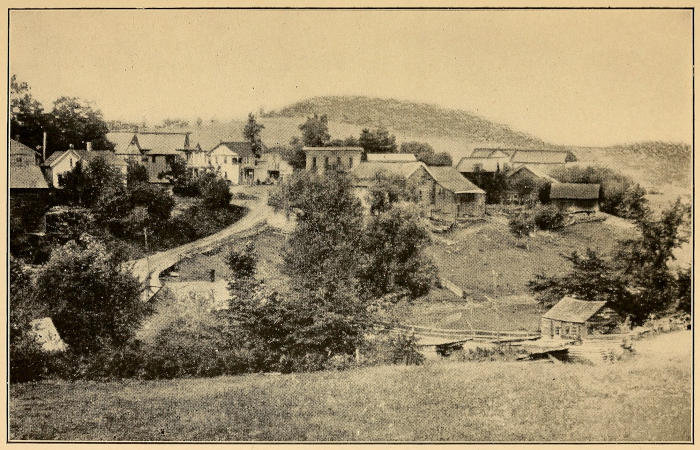

| Social Stagnancy is a Characteristic Trait of the Small Town and the Country | 22 |

| An Old Dingy, Dull-Grey Chapel on the Second Floor of the Administration Building was remodeled into what is now known as The Little Country Theater | 45 |

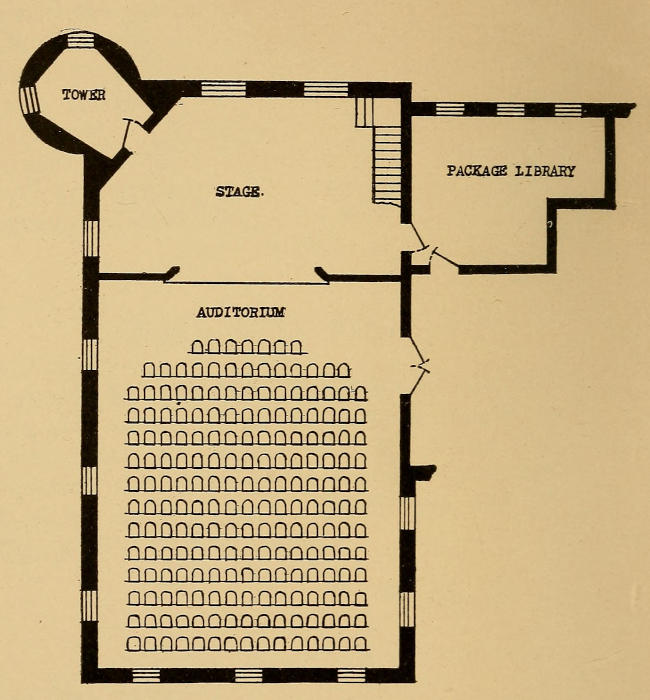

| It Has a Seating Capacity of Two Hundred | 53 |

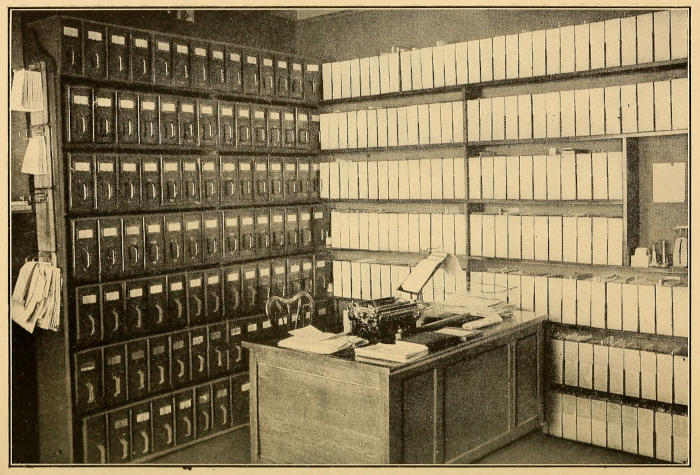

| The Package Library System | 55 |

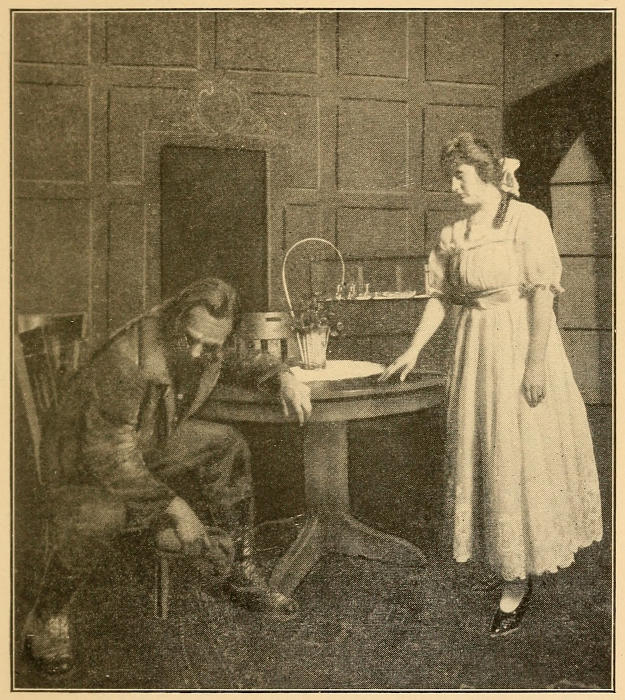

| A Farm Home Scene in Iceland Thirty Years Ago | 70 |

| Scene—“Leonarda” | 72 |

| Scene—“The Servant in the House” | 78 |

| Scene—“Back to the Farm” | 82 |

| The Pastimes of the Ages | 84 |

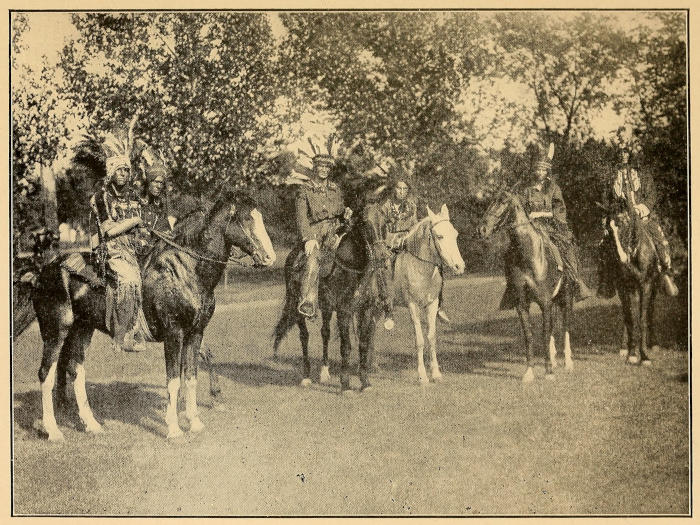

| Scene—“Sitting Bull-Custer” | 88 |

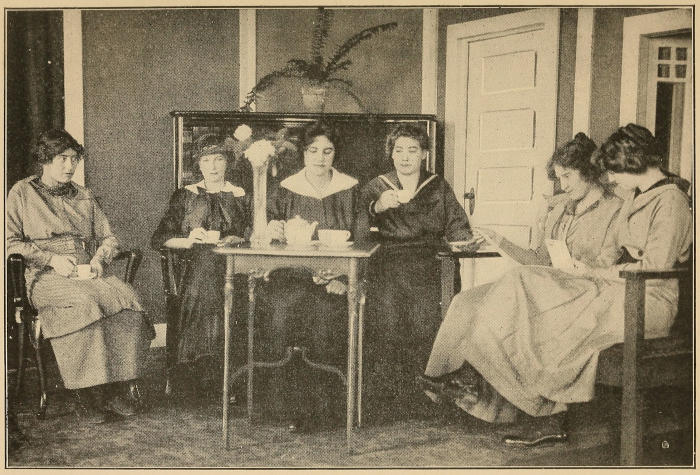

| Scene—“American Beauties,” A One Act Play | 92 |

| Scene—“A Bee in a Drone’s Hive” | 100 |

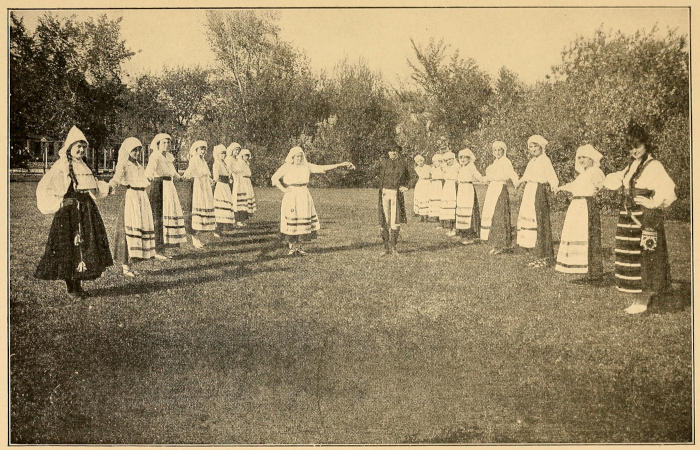

| Folk Dances, Parades, and Pageants have become an Integral Part of the Social Life of the State | 172 |

| Of the Fifty-three Counties in the State Thirty-five have County Play Days | 174 |

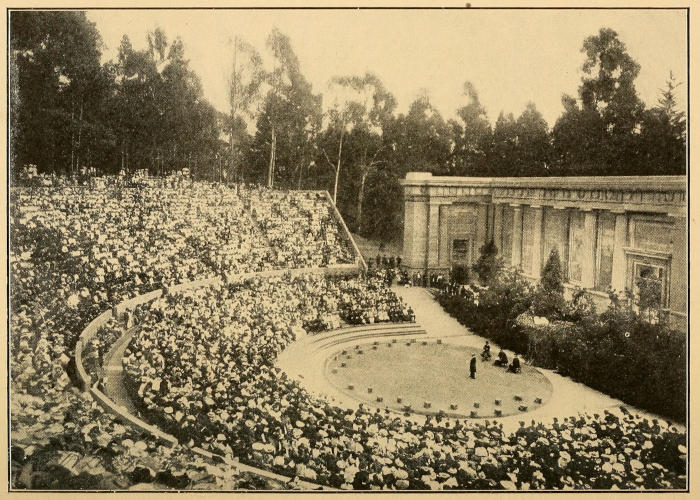

| The Greek Theater, University of California, Berkeley, California | 222 |

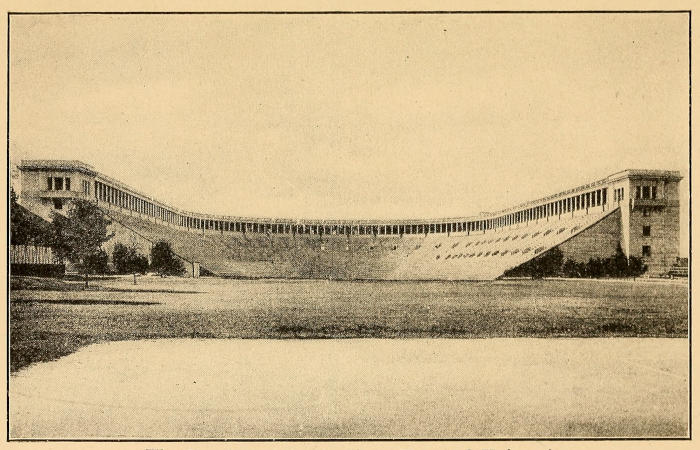

| “The Crescent,” One of America’s Largest Open Air Theaters, El Zagal Park, Fargo, North Dakota | 223 |

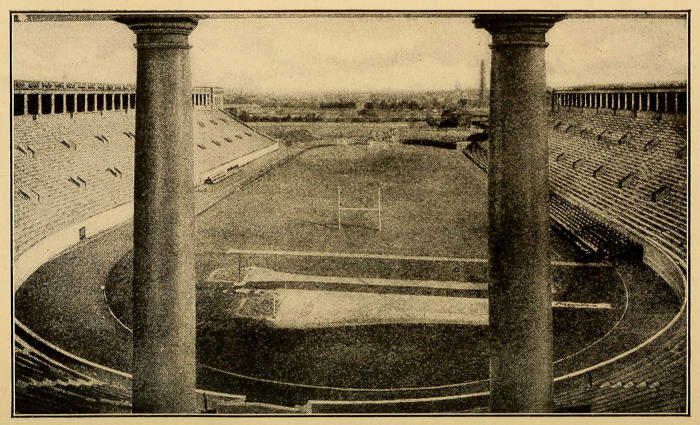

| The Stadium, Harvard University | 224 |

| The Interior of the Stadium | 225 |

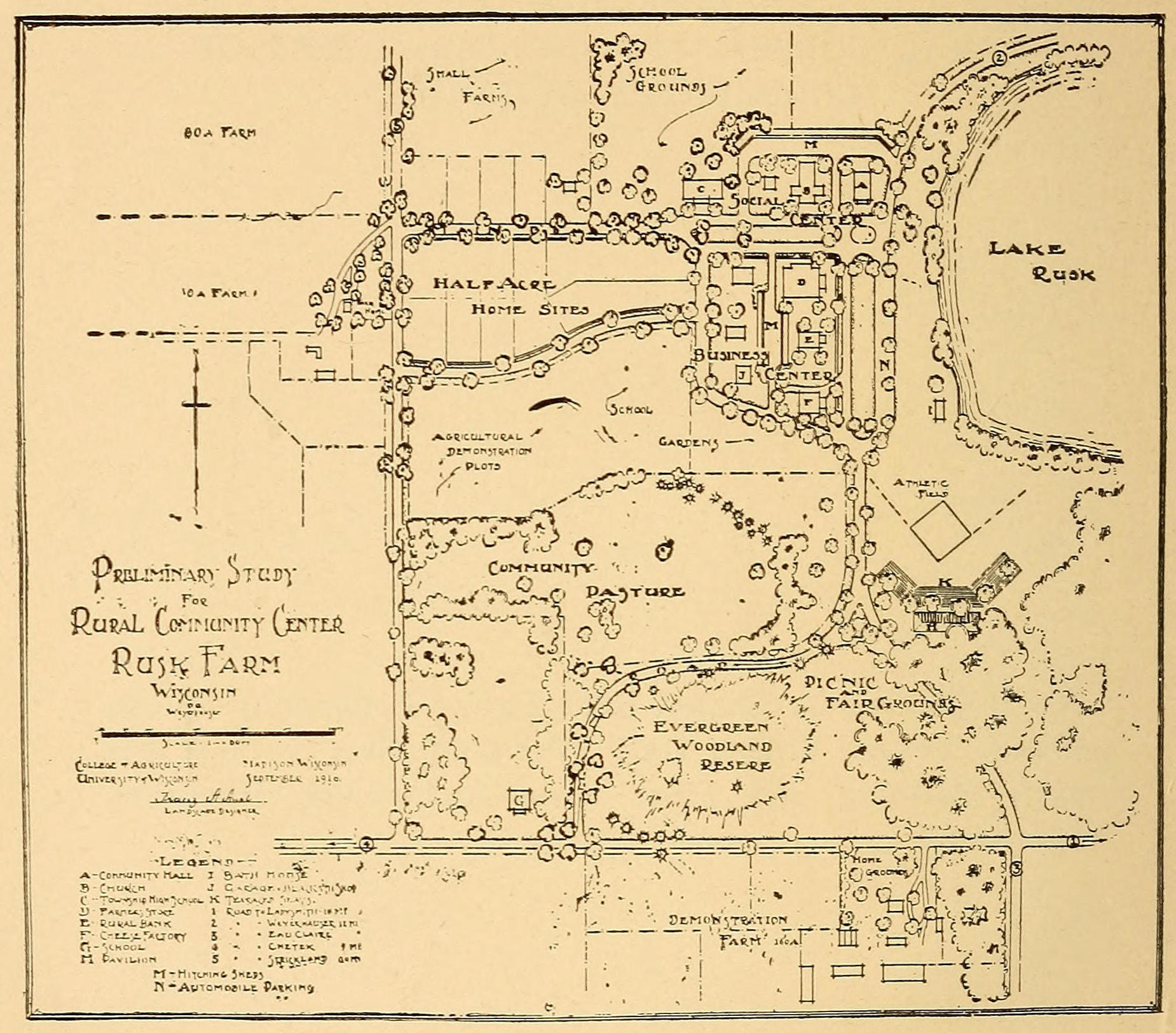

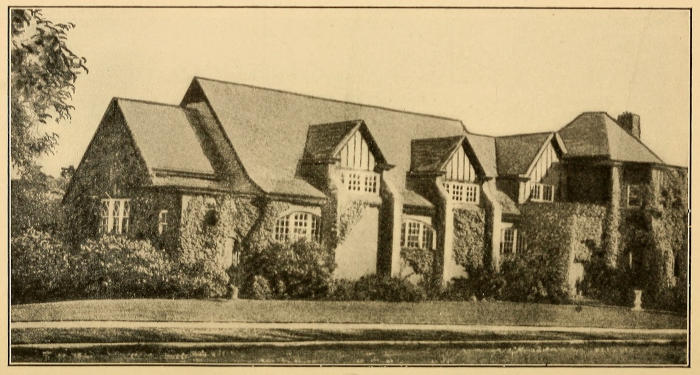

| Rural Community Center, Rusk Farm | 228 |

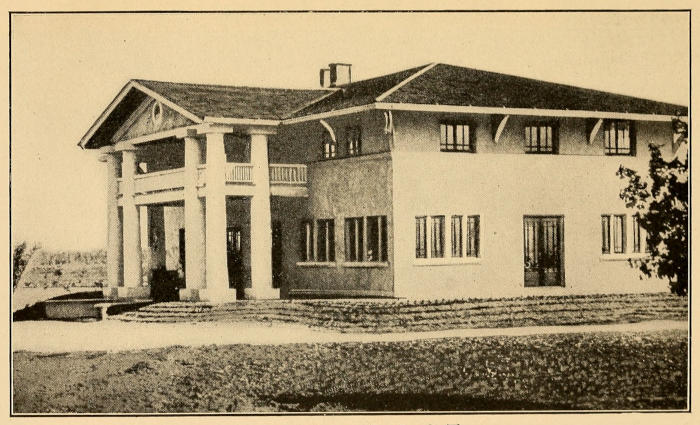

| Community House, Leeland, Texas | 229 |

| Village Hall, Wyoming, New York | 230 |

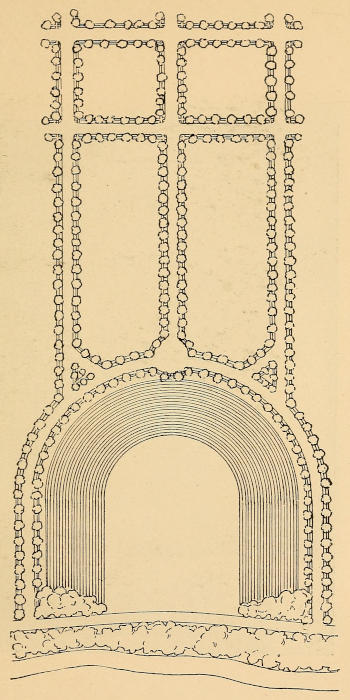

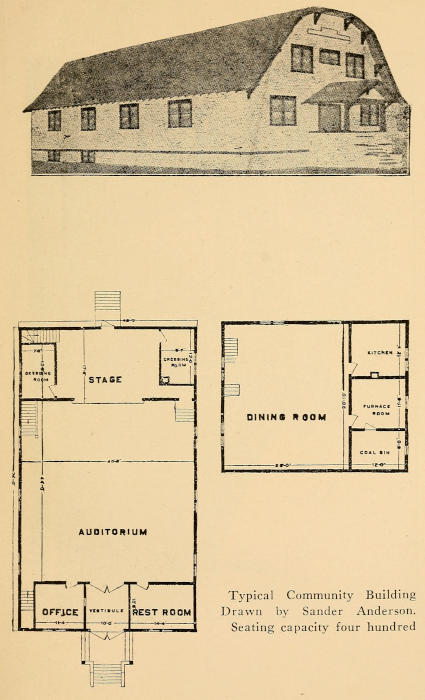

| Community Building and Floor Plan | 231 |

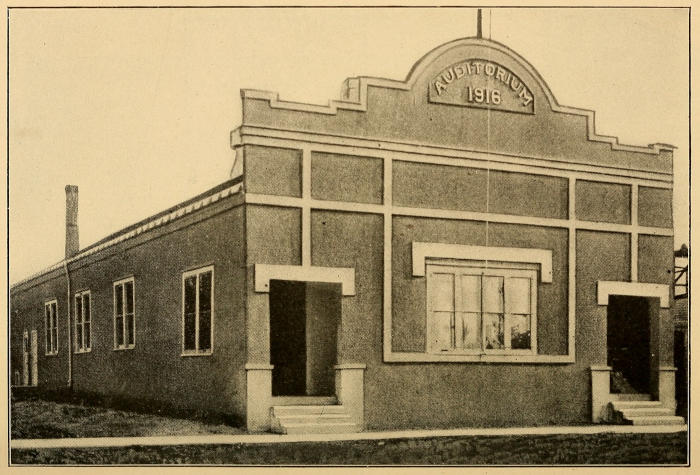

| Auditorium, Hendrum, Minnesota | 232 |

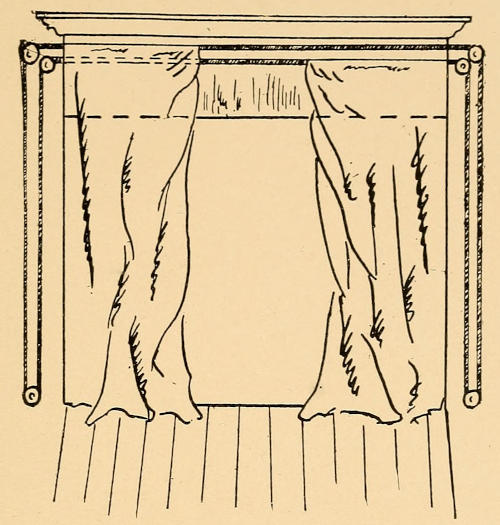

| Stage Designs | 235 |

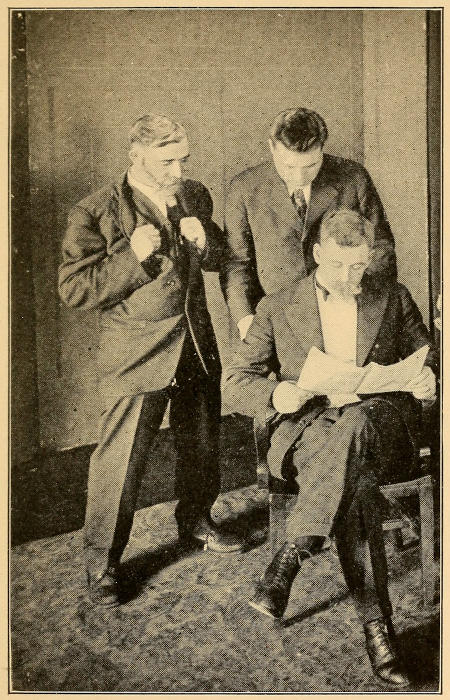

One day, about three weeks before the Christmas holidays, two young men came to see me. I shall never forget the incident because to me it marked one of the most fascinating episodes in the social life of country people. One of the young men was tall with broad shoulders and had light hair and grey eyes. The other was of medium height and had dark hair. His home was in Iceland. That they both had something important to say was evident from the expression on their faces. After a few moment’s hesitation, they told me they had thought out an idea for a play. Both of them were brimful of enthusiasm in regard to it. Whether or not they could produce it was a question. An obstacle stood in the way. Most of the scenes[4] were laid in Iceland. And what playhouse or village hall, especially a country theater, ever owned any scenery depicting home life, snow-capped mountains, and landscapes in that far-away region? Above all, there was no money to buy any, either.

“Perhaps we will meet again like the raindrops.”

When told that they would have to paint the scenery themselves, they looked somewhat surprised. It is doubtful whether either of them had ever painted anything more than his mother’s kitchen floor or perhaps whitewashed a fence or the interior of a barn. They finally decided to do the job. A painter was called over the phone who said he wouldn’t charge the boys a cent for the colors if they painted the scene. Up in an attic of a building near by there was an old faded pink curtain that had been cast aside. It was thought to be no longer useful. Within twenty-four hours the curtain was brought over and hoisted, and the floor of the stage adjacent to the office was covered with paint pails, brushes, and water colors. With dogged determination they decided to finish the painting during the holiday vacation. A few minutes before midnight on[5] New Year’s Eve the last stroke of the brush was made. The quaint cottage, the snow white-capped mountain, the tumbling waterfall and the steep ascending cliffs were painted in a manner which brought many favorable comments from competent art critics. The blending of the colors was magnificent. It was genuine art. The beauty of it all was that these two young men found that they could express themselves even on canvas.

Just as they had painted their scenery on the stage of the theater, so did they write their play, acting out each line before they put it in final form for presentation. Often they worked all night until four o’clock in the morning. They called their play “The Raindrops.” The theme is told in the second act of the play. The scene represents the interior of an Icelandic home. It is evening. The family circle has gathered. Some are sewing and others knitting. The children want to hear a story. Sveinn, one of the characters in the play, finally says to them, “All right then, if you are quiet, I will tell you the story of the raindrops who met in the sky.” And he narrates the following[6] which the children listen to with rapt attention.

“Once there were two raindrops away-way high up in the clouds. The sun had just lately smiled at them as they were playing in the big ocean, and his smile had drawn them up into the sky. Now as they danced and sported about in its radiance he decked them in all the bright and beautiful colors of the rainbow; and they were so happy over being rid of the dirt and salt that they almost forgot themselves for joy.

But somehow there seemed to be something that reminded them of the past. They felt as if they had met before. Finally one said, “Say, friend, haven’t we met before?” “That is just what I’ve been thinking,” said friend. “Where have you been, comrade?”

“I’ve been on the broad prairies on the west side of the big mountain that you see down there,” answered comrade.

“Oh,” said friend, “and I’ve been on the green slope on the east side of the mountain. I had a friend who fell at the same time as I did, and we were going to keep together, but[7] unfortunately he fell on the other side of the ridge.”

“That was too bad,” said comrade, “the same thing happened to me but my friend fell on the east side just close to that stone you see down there.”

“Why, that is just where I fell,” said friend. This was enough—they could scarcely contain themselves with joy over meeting and recognizing one another again.

After they had danced one another around for a while, shaken hands a dozen times or more, and slapped one another on the back till they were all out of breath, friend said, “Now, comrade, tell me all about everything that has happened to you.”

“And you’ll have to tell me everything that you have seen,” said comrade.

“Yes, I’ll do that,” said friend, and then comrade began:

“Well, I fell on the west side of that stone, as you know. At first I felt kind of bad, but I gradually got over it and began to move in the same direction as the others I saw around me. At first I could not move fast, for I was so[8] small that every little pebble blocked my road, but then the raindrops held a meeting and agreed to work together to help one another along and I joined the company to help form a pretty little brook. In this way we were able to push big stones out of our road and we were so happy that we laughed and played and danced in the sunlight which shone to the bottom of the brook, for we were not too many and we were all clean.

“Gradually more and more joined us till we became a big river. Nothing could any longer stand in our road and we became so proud of our strength that we tore up the earth and dug out a deep, deep path that everyone might see.

“But then our troubles began. We became so awfully dirty that the sun no longer reached any but those on top, while others were forced to stay in the dark. They groaned under the weight of those up higher, while at the same time they tore up from the bottom more and more filth.

“I wanted to get out of it all, but there didn’t seem to be any way. I tried to get up on the big, broad banks where all sorts of crops[9] were growing, but I was met and carried back by others rushing on into the river, evidently without realizing where they were going. The current tossed me about, first in the sunshine and then in the depths of darkness, and I had no rest till at last I got into the great ocean. There I rested and washed off most of the dirt.”

“I wish I could have seen the river,” said friend, “but why didn’t you spread out more, so as to help the crops on the plains and so that all might have sunlight?”

“I don’t know,” said comrade, “First we wanted to leave a deep path for others to see, and then later it seemed that we were helpless in the current that we ourselves had started. You must now tell me your story.”

“Yes,” said friend. “I fell on the east side of that stone, and when I couldn’t find you I started east, because I saw the sun there. After a while I bumped into a great big stone which was right across my path. It was such an ugly thing that I got angry and said, ‘Get out of my way, you ugly thing, or I’ll get all the other raindrops together and roll you out of the road.’

“Oh, no, do not do that,” said the stone, “for I am sheltering a beautiful flower from the wind, but I’ll lift myself up a little so you can crawl under.”

“It was awfully dark and nasty and creepy under the stone, and I didn’t like it a bit, but when I came out into the sunshine and saw the beautiful flowers on the other side I was glad that I hadn’t spoiled their shelter.”

“‘Isn’t this lovely?’ said a raindrop near me, ‘let us go and look at all the flowers.’ Then a crowd of raindrops that had gathered said, ‘Let us spread out more and more and give them all a drink,’ and we went among the flowers on the slope and in the valleys. As we watered them they smiled back at us till their smiles almost seemed brighter than the sunlight. When evening came we went down the little brooks over the waterfalls and hopped and danced in the eddy while we told one another about the things we had seen. There were raindrops from the glaciers and from the hot springs, from the lava fields and from the green grassy slopes, and from the lofty mountain peaks, where all the land could be[11] seen. Then we went on together singing over the level plains and into the ocean.”

For awhile neither one said anything. Then comrade spoke, “Yes, when I go back I’ll get the others to go with me and we’ll spread out more—and now I am going back. See the grain down there, how dry it is. Now I’m going to get the other raindrops to spread out over the plains and give all the plants a drink and in that way help everyone else.”

“But see the flowers there on the slope on the east side,” said friend. “They’ll fade if I don’t go down again to help them.”

“We’ll meet again,” said both, as they dashed off to help the flowers and the grain.

The story ends. A pause ensues and Herdis, the old, old lady in the play says, “Yes, we are all raindrops.”

It is a beautiful thought and exceptionally well worked out in the play. The raindrops are brothers. One’s name is Sveinn. He lives in Iceland. The other is Snorri. His home is America. Snorri crosses the ocean to tell Sveinn about America. Upon his arrival he meets a girl named Asta and falls in love with[12] her, little thinking that she is the betrothed of his brother Sveinn. Asta is a beautiful girl. She has large blue eyes and light hair which she wears in a long braid over her left shoulder. In act three, when speaking to Asta, Snorri says, “Sometimes I think I am the raindrop that fell on the other side of the ridge, and that my place may be there; but then I think of the many things I have learned to love here—the beautiful scenery, the midnight sun, the simple and unaffected manners of the people, their hospitality, and probably more than anything else some of the people I have come to know. A few of these especially I have learned to love.”

It does not dawn upon Snorri that Asta has given her hand to his brother Sveinn until the fourth and last act of the play. The scene is a most impressive one. It was something the authors had painted themselves. At the right stands the quaint little sky-blue cottage, with its long corrugated tin roof. To the left, the stony cliffs rise. In the distance the winding road, the tumbling waterfall, and snow-capped mountain can be seen. Near the doorway of[13] the cottage there is a large rock on which Asta often sits in the full red glow of the midnight sun.

As the curtain goes up Snorri enters, looks at his watch, and utters these words, “They are all asleep, but I must see her to-night.” He gently goes to the door, quietly raps, turns and looks at the scenery, and says: “How beautiful are these northern lights! I’ve seen them before stretching like a shimmering curtain across the northern horizon, with tongues of flame occasionally leaping across the heavens; but here they are above me, and all around me, till they light up the scene so that I can see even in the distance the rugged and snow-capped hills miles away. How truly the Icelandic nation resembles the country—like the old volcanoes which, while covered with a sheet of ice and snow, still have burning underneath, the eternal fires.”

Asta then appears in the doorway and exclaims, “Snorri.” After an exchange of greetings they sit down and talk. Snorri tells Asta of his love and finally asks her to become his wife. Asta is silent. She turns and looks at[14] the northern lights, then bows her head and with her hands carelessly thrown over her knees she tells him that it cannot be—that it is Sveinn.

Snorri arises, moves away, covers his face with his hands and exclaims, “Oh, God! I never thought of that. What a blind fool I have been!” As Asta starts to comfort him Sveinn appears in the doorway, sees them and starts to turn away, but in so doing makes a little noise. Snorri startled, quickly looks around and says, “Sveinn, come here. I have been blind; will you forgive me?” Then he takes Asta’s hand and places it in Sveinn’s, bids them good-by and starts to leave.

Sveinn says, “Snorri! Where are you going? You are not leaving us at this time of night, and in sorrow?”

Snorri, returning, looks at the quaint little cottage, the waterfall, and then at Asta and Sveinn, pauses a moment, and says, “Perhaps we shall meet again—like the raindrops.” The curtain falls and the play ends.

Neither of these young men who wrote the play ever had any ambition to become a playwright,[15] a scene painter, or an actor. To-day, one is a successful country-life worker in the great northwest. The other is interested in harnessing the water power which is so abundant in his native land.

When the play was presented, the audience sat spellbound, evidently realizing that two country lads had found hidden life forces in themselves which they never knew they possessed. All they needed, like thousands of others who live in the country and even in the city, was just a chance to express themselves.

Authors of play—M. Thorfinnson and E. Briem.

There are literally millions of people in country communities to-day whose abilities along various lines have been hidden, simply because they have never had an opportunity to give expression to their talents. In many respects this lack of self-expression has been due to the social conditions existing in the country, the narrow-minded attitude of society toward those who till the soil, and the absence of those forces which seek to arouse the creative instincts and stimulate that imagination and initiative in country people which mean leadership.

Social stagnancy is a characteristic trait of the small town and the country. Community spirit is often at a low ebb. Because of the stupid monotony of the village and country existence, the tendency of the people young and[20] old is to move to larger centers of population. Young people leave the small town and the country because of its deadly dullness. They want Life. The emptiness of rural environment does not appeal to them. The attitude of mind of the country youth is best expressed by Gray in his “Elegy Written in a Country Church-yard” which runs as follows:

Many young people find the town and country dead simply because they crave fellowship and social enjoyment. When an afternoon local train passes through a certain section of any state, people gather at every station, some to meet their friends, others to bid their friends farewell, and dozens to see some form of life. With many it is the only excitement that enters their lives, except on extraordinary occasions. After the harvest many a country lad goes to the city to enjoy a feast of entertainment, in order to satisfy his social hunger.

A few years ago the national Department of[21] Agriculture sent out hundreds of letters to country women, asking them what would make life in the country districts more attractive. Hundreds of the replies which were received from practically every section of America told the story of social starvation and the needs of country communities. One woman from Kansas in her reply wrote:

“We hope you can help us to consolidate schools and plan them under a commission of experts in school efficiency and community education. Through this commission we could arrange clubs, social unions, and social, instructive, and educational entertainments. We ought not to be compelled to go to town for doubtful amusements, but, rousing the civic pride of the community, have the best at home.”

Another one from Wyoming in her letter stated that she thought the country child had the same right to culture and refinement as the city child. A woman whose home was in Massachusetts gave the following suggestions in her reply:

“On the side of overcoming the emptiness of rural life; articles suggesting courses of reading both along the line of better farming[22] and of subjects of public interest. Perhaps the wider use of the rural school or church for social centers, or for discussion by farmers, their wives, sons and daughters might be suggested.”

A letter written from Florida contained the following:

“First, a community center where good lectures, good music, readings, and demonstrations might be enjoyed by all, a public library station. We feel if circulating libraries containing books that can be suggested on purity, hygiene, social service, and scientific instruction, that our women in the rural districts need to read for the protection of their children; also books on farming and poultry raising, botany, culture of flowers, and many other themes that will help them to discover the special charm and advantage of living in the pure air and being familiar with the beauties of nature and thereby make our people desire to stay on the farms.”

Social Stagnancy is a Characteristic Trait of the Small Town and the Country

A letter from Tennessee said: “Education is the first thing needed; education of every kind. Not simply agricultural education, although that has its place; not merely the primary training offered by the public schools in arithmetic, reading, grammar, etc. I mean the education that unfastens doors and opens up vistas; the education that includes travel, college, acquaintance with people of culture; the[23] education that makes one forget the drudgery of to-day in the hope of to-morrow. Sarah Barnwell Elliott makes a character in one of her stories say that the difference between himself (a mountaineer) and the people of the university town is ‘vittles and seein’ fur.’ The language of culture would probably translate that into ‘environment and vision.’ It is the ‘seein’ fur’ that farm women need most, although lots of good might be done by working some on the ‘vittles.’ Fried pork and sirup and hot biscuit and coffee have had a lot to do with the ‘vision’ of many a farmer and farmer’s wife. A good digestion has much to do with our outlook on life. Education is such an end in itself, if it were never of practical use. But one needs it all on the farm and a thousand times more. ‘Knowledge is power,’ as I learned years ago from my copy book. But even if it were not, it is a solace for pain and a panacea for loneliness. You may teach us farm women to kill flies, stop eating pork, and ventilate our homes; but if you will put in us the thirst for knowledge you will not need to do these things. We will do them ourselves.”

A note from North Carolina read something like this:

“The country woman needs education, recreation, and a better social life. If broad-minded, sensible women could be appointed to make monthly lectures at every public schoolhouse[24] throughout the country, telling them how and what to do, getting them together, and interesting them in good literature and showing them their advantages, giving good advice, something like a ‘woman’s department’ in magazines, this would fill a great need in the life of country women. Increase our social life and you increase our pleasures, and an increase of pleasure means an increase of good work.”

All these answers and many more show something of the social conditions in the country so far as women are concerned. In other words, older people desert the country because they want better living conditions and more social and educational advantages for themselves and their children. Moral degeneracy in the country, like the city, is usually due to lack of proper social recreation. When people have something healthful with which to occupy their minds, they scarcely ever think of wrong-doing. A noted student of social problems recently said that the barrenness of country life for the girl growing into womanhood, hungry for amusement, is one reason why so many girls in the country go to the city. Students of science attribute the cause of many of the cases of insanity among country people to loneliness[25] and monotony. That something fundamental must be done along social lines in the country communities in order to help people find themselves, nobody will dispute. Already mechanical devices, transportation facilities, and methods of communication have done much to eliminate the drudgery, to do away with isolation, and to make country life more attractive.

An influence which has done a good deal to stifle expression in country people has been the narrow-minded attitude certain elements in society have taken toward those who till the soil. When these elements have wanted to belittle their city friends’ intelligence or social standing, they have usually dubbed them “old farmers.” Briefly stated, the quickest way to insult a man’s thinking power or social position has been to give him the title “farmer.” The world has not entirely gotten over the “Hey-Rube” idea about those who produce civilization’s food supply. A certain stigma is still attached to the vocation. As a group, country people have in many places been socially ostracized for centuries. A social barrier still exists between the city-bred girl and the[26] country-bred boy. As a result, all these things have had a tendency to destroy the country man’s pride in his profession. This has weakened his morale and his one ambition has been to get out of something in which he cannot be on an equal with other people, and consequently he has retired. Goldsmith in “The Deserted Village” hit the nail on the head when he said:

To be an honest tiller of the soil, to be actively engaged in feeding humanity, should be one of the noblest callings known to mankind and carry with it a social prestige. The Chinese Emperor used to plow a furrow of land once a year to stamp his approval upon agriculture. The reason Washington, Lincoln, Justin Morrill, and Roosevelt became so keenly interested in country life was that they saw the significance of it and its importance to the world. George Washington was a farmer, a country gentleman. Mount Vernon is a[27] country estate, a large farm. The father of our country believed that a great country people was the basic foundation of a great America. Thomas Jefferson once said, “The chosen people are those who till the soil.” When you ridicule any people, they are not likely to express their talents and the finer instincts which lie hidden in them. A weak rural morale eventually means rural decay. The heart of rural America will never beat true until society looks upon agriculture as a life, as something to get into and not steer away from or get out of its environment.

Another factor which has retarded the expression of the hidden abilities of those who live in the small towns and country communities has been the absence of any force which seeks to arouse the creative instincts and to stimulate the imagination and initiative. Even to-day, those agencies in charge of country-life problems, as well as city life, direct very little of their energies into channels which give color and romance and a social spirit to these folks. The most interesting part of any country community or neighborhood is the people who live[28] in it. Unless they are satisfied with their condition, it is little use to talk better farming. A retired farmer is usually one who is dissatisfied with country life. A social vision must be discovered in the country, that will not only keep great men who are country born in the country, but also attract others who live in the cities.

The impulse to build up a community spirit in a rural neighborhood may come from without, but the true genuine work of making country life more attractive must come from within. The country people themselves must work out their own civilization. A country town or district must have an individuality or mind of its own. The mind of a community is the mind of the people who live in it. If they are big and broad and generous, so is the community. Folks are folks, whether they live in the city or country. In most respects their problems are identical.

It is a natural condition for people to crave self-expression. In years gone by men who have been born and reared on the farm have left it and gone to the city, in order to find a[29] place for the expression of their talents. This migration has done more to hinder than to set forward the cause of civilization. People who live in the country must find their true expression in their respective neighborhoods, just as much as do people who live in the city. You cannot continually take everything out of the country and cease to put anything back into it. The city has always meant expression—the country, repression. Talent usually goes to the congested centers of population to express itself. For generations when a young man or woman has had superior ability along some particular line and lived in the country, their friends have always advised them to move to a large center of population where their talents would find a ready expression. You and I, for instance, who have encouraged them to go hither, have never thought that we were sacrificing the country to build the city. This has been a mistake. We all know it.

Over fifty years ago a country doctor became the father of two boys. In age they were five years apart. The doctor brought them up well and sent them away to a medical school.[30] Unlike most country-bred boys who go to large cities, when they finished their courses they went back to the old home town and began their practice. By using their creative instincts, organizing power, imagination, and initiative, it was not long before they became nationally known. People call their establishment “the clinic in the cornfields.” To-day these “country doctors” treat over fifty thousand patients. Their names are known wherever medical science is known. Railroads run special sleepers hundreds of miles to their old home town in Olmstead County, Minnesota, which, by the way, is one of the richest agricultural counties in America. The great big thing about these two men is that they found an opportunity for the expression of their talents in a typical country community. They didn’t go to a large city, they made thousands of city people come to them.

Conservatively speaking, there are over ten thousand small towns in America to-day. More than ten million people live in them. These communities are often meeting places for the millions whose homes are in the open country.[31] Rural folks still think of a community as that territory with its people which lies within the team haul of a given center. It is out in these places where the silent common people dwell. It is in these neighborhood laboratories that a new vision of country life is being developed. They are the cradles of democracy. It is here that a force is necessary to democratize art so the common people can appreciate it, science so they can use it, government so they can take a part in it, and recreation so they can enjoy it.

The former Secretary of Agriculture aptly expressed the importance of the problem when he said:

“The real concern in America over the movement of rural population to urban centers is whether those who remain in agriculture after the normal contribution to the city are the strong, intelligent, well seasoned families, in which the best traditions of agriculture and citizenship have been lodged from generation to generation. The present universal cry of ‘keep the boy on the farm’ should be expanded into a public sentiment for making country life more attractive in every way. When farming is made profitable and when the better things of life are brought in increasing measure to the rural community, the great motives which lead[32] youth and middle age to leave the country districts will be removed. In order to assure a continuance of the best strains of farm people in agriculture, there can be no relaxation of the present movements for a better country life, economic, social, and educational.”

A skilled physician when he visits a sick room always diagnoses the case of the patient before he administers a remedy. In order to comprehend thoroughly the tremendous significance the Land of the Dacotahs bears in its relation to the solution of the problem of country life in America, one must know something about the commonwealth and its people.

North Dakota is a prairie state. Its land area comprises seventy-one thousand square miles of a rich black soil equal in its fertility to the deposits at the delta of the River Nile in Egypt. There are over forty million acres of tillable land. The state has one of the largest undeveloped lignite coal areas in the world.

Its climate is invigorating. The air is dry and wholesome. The summer months are delightful.[36] The fields of golden grain are inviting. The winters, on the other hand, are long and dreary, and naturally lonely. People are prone to judge the climate of the state by its blizzards. Those who do, forget this fact—a vigorous climate always develops a healthy and vigorous people. No geographical barriers break the monotony of the lonesome prairie existence. A deadly dullness hovers over each community.

The population of the state is distinctly rural. Over seventy per cent of the people live in un-incorporated territory. Seven out of every eight persons are classed as rural. The vocation of the masses is agriculture. Everybody, everywhere, every day in the state talks agriculture. At the present time there are about two hundred towns with less than five hundred inhabitants.

One of the most interesting characteristics of this prairie commonwealth is its population. They are a sturdy people, strong in heart and broad in mental vision. The romance of the Indian and the cowboy, the fur-trader and the trapper, has been the theme of many an interesting[37] tale. The first white settler, who took a knife and on bended knee cut squares of sod and built a shanty and faced long hard winters on this northern prairie, is a character the whole world loves and honors. Several years ago an old schoolmaster, whose home is not so very far from Minnehaha Falls, delivered a “Message to the Northwest” which typifies the spirit of these people. He said in part:

“I am an old man now, and have seen many things in the world. I have seen this great country that we speak of as the Northwest, come, in my lifetime, to be populous and rich. The forest has fallen before the pioneer, the field has blossomed, and the cities have risen to greatness. If there is anything that an old man eighty years of age could say to a people among whom he has spent the happiest days of his life, it is this: We live in the most blessed country in the world. The things we have accomplished are only the beginning. As the years go on, and always we increase our strength, our power, and our wealth, we must not depart from the simple teachings of our youth. For the moral fundamentals are the same and unchangeable. Here in the Northwest we shall make a race of men that shall inherit the earth. Here in the distant years, when I and others who have labored with me[38] shall long have been forgotten, there will be a power in material accomplishment, in spiritual attainment, in wealth, strength, and moral influence, the like of which the world has not yet seen. This I firmly believe. And the people of the Northwest, moving ever forward to greater things, will accomplish all this as they adhere always to the moral fundamentals, and not otherwise.”

The twenty-odd nationalities who live in the Dacotahs came from lands where folklore was a part of their everyday life. Many a Norseman—and there are nearly two hundred thousand people of Scandinavian origin, Norwegians, Danes, Swedes, and Icelanders, in the state—knows the story of Ole Bull, the famous violinist, who when a lad used to take his instrument, go out in the country near the waterfalls, listen attentively to the water as it rushed over the abyss, then take his violin, place it under his chin, and draw the bow across the strings, to see whether he could imitate the mysterious sounds. Most of these Norse people live in the northern and eastern section of the state. The hundred thousand citizens whose ancestors came from the British Isles—the English, the Welsh, the Scotch, the Irish,[39] and the Canadians—know something of Shakespeare and Synge and Bobbie Burns. Ten years ago there were sixty thousand people of Russian descent and forty-five thousand of Teutonic origin in the state. They were acquainted with Tolstoy and Wagner. Greeks, Italians, and Turks, besides many other nationalities, live in scattered sections of the state. In fact, seventy-two per cent of the citizens of the state are either foreign born or of foreign descent. All these people came originally from countries whose civilizations are much older than our own. All have inherited a poetry, a drama, an art, a life in their previous national existence, which, if brought to light through the medium of some great American ideal and force, would give to the state and the country a rural civilization such as has never been heard of in the history of the world. All these people are firm believers in American ideals.

One excellent feature in connection with the life of the people who live in Hiawatha’s Land of the Dacotahs is their attitude toward education. They believe that knowledge is power. Out on these prairies they have erected schoolhouses[40] for the training of their youth. To-day there are nearly five hundred consolidated schools in the state. One hundred and fifty of these are in the open country, dozens of which are many miles from any railroad. Twenty-three per cent of the state area is served by this class of schools. Much of the social life of a community is centered around the school, the church, the village or town hall, and the home. The greater the number of activities these institutions indulge in for the social and civic betterment of the whole community, the more quickly the people find themselves and become contented with their surroundings.

In most respects, however, North Dakota is not unlike other states. People there are actually hungry for social recreation. The prairies are lonely in the winter. Thousands of young men and women whose homes are in rural communities, when asked what they wanted out in the country most, have responded, “More Life.” The heart hunger of folks for other folks is just the same there as everywhere.

With a knowledge of these basic facts in mind, as well as a personal acquaintance with hundreds of young men and women whose homes are in small communities and country districts, the idea of The Little Country Theater was conceived by the author. A careful study of hundreds and literally thousands of requests received from every section of the state, as well as of America and from many foreign countries, for suitable material for presentation on public programs and at public functions, showed the necessity of a country life laboratory to test out various kinds of programs.

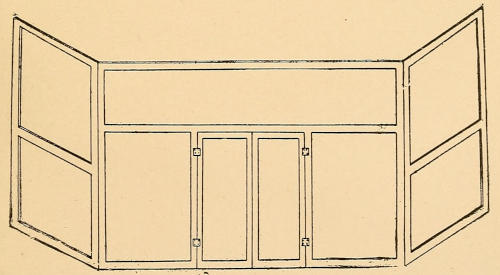

The idea conceived became an actual reality when an old, dingy, dull-grey chapel on the second floor of the administration building at the North Dakota Agricultural College,[44] located at Fargo, North Dakota, was remodeled into what is now known as “The Little Country Theater.” It was opened the tenth day of February in the year nineteen hundred and fourteen. In appearance it is most fascinating. It is simply a large playhouse put under a reducing glass. It is just the size of an average country town hall. It has a seating capacity of two hundred. The stage is thirty feet in width, twenty feet in depth, having a proscenium opening of ten feet in height and fifteen feet in width. There are no boxes and balconies. The decorations are plain and simple.

The color scheme is green and gold, the gold predominating. Three beams finished in golden oak cross the mansard ceiling, the beams projecting down several feet on each side wall, from which frosted light bowls and globes are suspended by brass log chains, the indirect lighting giving a soft and subdued tone to the whole theater. The eight large windows are hung with tasteful green draperies. The curtain is a tree-shade green velour. The birch-stained seats are broad and not crowded together.[45] There is a place for a stereopticon and a moving picture machine. The scenery is simple and plain. Whenever possible, green curtains are used. Simplicity is the keynote of the theater. It is an example of what can be done with hundreds of village halls, unused portions of school houses, vacant country stores and basements of country churches in communities.

An Old Dingy, Dull-Grey Chapel on the Second Floor of the Administration Building was Remodeled Into What Is Now Known as The Little Country Theater

There are three unique features in connection with The Little Country Theater which deserve special mention—the tower, the attic or “hayloft,” and the package library system.

The tower is just to the right of the lower end of the stage. It, too, is plain and simple. It is used as a study and contains materials gathered from all over the world on the social side of country life.

The attic is to the left of the stage and up a flight of stairs. It was formerly an old garret. For over twenty years it was unused. It is the workshop of the theater and contains committee rooms, dressing rooms, a property room, a costume wardrobe, a small kitchen, and a dining room which will comfortably seat[46] seventy-five persons. In many respects it corresponds to the basement of a community building, a church, or an addition tacked on to a village hall. It is often used for an exhibit hall or a scenic studio. In short, The Little Country Theater is a typical rural community center, a country-life laboratory. One significant feature about this experimental laboratory is that the birch-stained seats, the green curtains, the scenic effects, the stage properties, the five hundred costumes, the furniture, the dishes, and all the other necessities have been bought with funds taken in from entertainments and plays, thereby demonstrating that any community can do the same. Endowments in the country are always difficult to raise.

Twelve years ago a country school-teacher sent in a request for some program material. Three personal copies of plays were sent to her, one of which she staged. It was not very long before others heard where she secured her data and many inquiries followed. Out of this request, together with an acquaintance with an old, white-haired man who had just started a similar system at a leading western university,[47] the package library idea came into existence. It is a sort of an intellectual rural free delivery. One might call it the backbone of The Little Country Theater. In order to understand thoroughly the importance of the service which the system renders it will be necessary to say something about the aim of the work, its scope, how the data is gathered, and the practical results already obtained.

The aim of the package library system is to vitalize all the sources of information which can be used for material for presentation on public programs. Its chief object is to make the schools, the churches, the homes, and the village or town halls, centers of community activity where men and women and their children, young and old, can meet just to talk over things, to find out the normal human life forces and life processes, and really to discover themselves.

The field of work is the state and its people. The scope of the service is broad. Any individual or group of people in the state can obtain program material simply by writing and asking for it.

In order to render the best aid possible, the system gathers data and information from reliable sources. Briefs upon subjects relating to country life, copies of festivals, pageants, plays, readings, dialogues, pictures of floats, parades, processions, exhibit arrangements, costume designs, character portrayals, plans of stages, auditoriums, open-air theaters, community buildings, constitutions of all kinds of organizations, catalogues of book publishers—in short, every kind of material necessary in building a program which will help people to express themselves—are loaned for reading purposes to citizens of the state. A few minutes’ talk with anybody interested in getting up programs in small communities will soon show the dearth of material along these lines.

In the years gone by, as well as in the present, the letters which come to the desk daily have told many an interesting story.

An energetic teacher in a country school in the northern part of the state sent for several copies of plays and play catalogues. None of the plays sent suited her. She decided to give an original play, “The Comedy.” When[49] asked for a description of the staging of the original production, she sent the following letter, which is indicative of what people really can do in the country to find themselves.

“When I wrote to you about ‘The Comedy,’ I do not know what idea I gave you of it; perhaps not a very true one; so I am sending you a copy. The little song is one I learned from a victrola record, so the music may not be correct, but with a little originality, can be used. The little play has the quality of making the people expect something extraordinary, but when performed, the parts are funny, but still not funny enough to produce a ‘roar.’ They are remembered and spoken of long afterwards. Now around here we often hear parts spoken of. I enjoyed training the young people, and they were quite successful. I have found that every place I go people in the country enjoy the school programs very much and speak of them often. We wanted to take some pictures, but could not. The weather was so cloudy before and afterward that we could not take any, but may this Sunday afternoon. I wish I knew just what to write about or just what you wish to know. I liked our arrangements of lights. We only had lanterns. A dressing room was curtained off and the rest of the space clear. We hung four lanterns in a row, one below the other, and had one standing on the floor at the side opposite from the[50] dressing room, and then one on the floor and one held by the man who pulled the curtain on the other side. This gave splendid light. There was no light near the audience except at the organ.

“Hoping you will enjoy reading ‘The Comedy’ as much as we did playing and writing it, I am

“Yours sincerely,

“A. K.”

There is something very human about a letter when it solicits your personal help and suggestions. To quote from several of the thousands received will not only show the need for the package library, because of the scarcity of material in small towns and the country, but also give an insight into the mind of the people themselves.

“Barton, N. D., October 23, 1911.

“Gentlemen:—Would you kindly send a copy of the following plays: Corner Store, The Deestrick Skule, Country Romance, Pa’s Picnic, A Rival by Request, School for Scandal, Tempest in a Tea-pot, Which is Which.

“I wish to get up an entertainment in my school and wish you could help me select a play which would not require too much room and too many actors. Will return the ones I do[51] not use immediately. Any favor which you may render will be greatly appreciated.

“Very respectfully,

“E. S.”

“Gilby, N. D., Jan. 18, 1912.

“Dear Sir:—

“Will you please forward your list of amateur plays. We are about to stage the annual H. S. play, and find it rather difficult to select a play not too sentimental in characters. We would like one for 5-7 boys and 5-8 girls. Our hall is small with cramped stage room, and the scene must be quite simple. If you have any suggestions to offer or any sample play to forward for examination, will you kindly let us know as soon as possible.

“Yours very truly,

“E. F. L.”

Ross, N. D., Jan. 22, 1913.

“Dear Sir:—

“Enclosed find plays, also stamps to cover mailing expenses.

“Please send me the following amateur plays: Exerbition of District Skule, Mock Trial, Scrap of Paper, Sugar and Cream. Please send also the following as listed under package libraries: Manual Training, School House as an Art Gallery, School House as a Social Center, Fireless Cooker.

“Yours truly,

“M. C.”

“Backoo, N. D., Jan. 24, 1914.

“Dear Sir:—

“I rec’d the packet of information on Country Life and will return it after our next meeting the 27th. Can you send me two or three dialogues suitable for a Literary Society in a rural district. We have 6 or 8 young ladies that might take part but very few young men. And will you suggest a few subjects for debate of interest and benefit to a country community.

“Yours truly,

“J. B. P.”

“Austin, N. D., Feb. 11, 1914.

“Gentlemen:—

“I should be very glad if you could send me a short play of say 30 or 45 minutes length as you mentioned in Nov. We are using the schoolhouse as a meeting place and so have not much room on the stage. Could use one requiring from 4 to 8 characters.

“Yours truly,

“H. W. B.”

It Has a Seating Capacity of Two Hundred

“Verona, N. D., Feb. 14, 1915.

“Dear Mr. ⸺:

“While to-day the blizzard rages outside—inside, thanks largely to yours and your department’s work, many of us will be felicitously occupied with the mental delights of literary preparation and participation. Our society is thriving splendidly. Last Friday another similar[53] society was started in the country north of here. Went out and helped them organize. They named their club the Greenville Booster Club. Some of the leading lights are of the country’s most substantial farmers. Suggest that you send literature on club procedure to their program committee. This community, both town and country north, has for the past many years been the scene of much senseless strife over town matters, school matters, etc.

“I believe the dawn of an era of good feeling is at hand. These get-together clubs are bound to greatly facilitate matters that way. At their next meeting I am on their debate and supposed to get up a paper to read on any topic I choose, besides. Now with carrying the mail, writing for our newspaper, practicing and singing with the M. E. choir, also our literary male quartet, to say nothing of debating and declaiming and writing for two literaries my time is all taken up. Could you find me something suitable for a reading?

“Sincerely yours,

“A. B.”

“Regan, N. Dak., Nov. 30, 1917.

“Mr. A. ⸺:

“My sister sent to you for some plays which we are returning. We put on ‘The Lonelyville Social Club’ after ten days’ practice and cleared $39.10 in Regan and $93.00 when we played it last night in Wilton. It took well[54] and we are much pleased with our effort. The proceeds go to the Red Cross.

“Thanking you most sincerely, I am

“V. C. P. (and the rest of the troop).”

“Hensel, N. D., Mar. 15, 1918.

“Dear Friend:

“I received the paint which you sent me. I thank you very much for it, it certainly came in handy. Do you need it back or if not how much does it cost? I would rather buy it if you can spare it.

“The play was a success. We had a big crowd everywhere. Everybody seemed to like it. Some proclaimed it to be the best home talent play they had seen. We have played it four times. Whether we play more has not been decided.

“Yours truly,

“A. H.”

“Overly, N. D., Mar. 21, 1918.

“Gentlemen:—

“Have you any book from the library that would help with a Patriotic entertainment to be given in this community for the benefit of the Red Cross? If you can offer suggestions also, we will appreciate it.

“Thanking you, I am, truly yours,

“G. L. D.”

The Package Library System

“Lansford, N. D., May 25, 1920.

“Dear Mr. A.:

“As a teacher in a rural school I gave a program at our school on last Saturday evening. We had an audience of about seventy-five people and they simply went wild over our program. Our school has an enrollment of four girls, being the only school in the county where only girls are enrolled and also the smallest school in the county. Our program lasted two hours and twenty minutes and was given by the four girls.

“We have been asked to give our entertainment in the hall in Lansford. Now I want to ask you for a suggestion. Don’t you think that in a make-up for ‘grandmothers’ that blocking out teeth and also for making the face appear wrinkled’ would improve the parts in which grandmothers take part?

“Would it be possible for you to send me the things necessary as I would like to get them as soon as possible and do not know where to send for them. If you can get them for me I shall send the money also postage, etc., as soon as I receive them.

“Trusting that this will not inconvenience you greatly, I remain,

“Very truly yours,

“E. B.”

It is not an uncommon occurrence to get a long distance call at eleven o’clock at night[56] from someone two or three hundred miles away, asking for information. Telegrams are a common thing. Conferences with people who come from different communities for advice are frequent. The tower, the attic, and the package library are an integral part of the theater.

The aim of The Little Country Theater is to produce such plays and exercises as can be easily staged in a country schoolhouse, the basement of a country church, the sitting room of a farm home, the village or town hall, or any place where people assemble for social betterment. Its principal function is to stimulate an interest in good clean drama and original entertainment among the people living in the open country and villages, in order to help them find themselves, that they may become better satisfied with the community in which they live. In other words, its real purpose is to use the drama and all that goes with the drama as a force in getting people together and acquainted with each other, in order that they may find out the hidden life forces of nature itself. Instead of making the drama a luxury for the classes, its aim is to make it an instrument[57] for the enlightenment and enjoyment of the masses.

In a country town nothing attracts so much attention, proves so popular, pleases so many, or causes so much favorable comment as a home talent play. It is doubtful whether Sir Horace Plunkett ever appreciated the significance of the statement he once made when he said that the simplest piece of amateur acting or singing done in the village hall by one of the villagers would create more enthusiasm among his friends and neighbors than could be excited by the most consummate performance of a professional in a great theater where no one in the audience knew or cared for the performer. Nothing interests people in each other so much as habitually working together. It’s one way people find themselves. A home talent play not only affords such an opportunity, but it also unconsciously introduces a friendly feeling in a neighborhood. It develops a community spirit because it is something everybody wants to make a success, regardless of the local jealousies or differences of opinion. When[58] a country town develops a community consciousness, it satisfies its inhabitants.

The drama is a medium through which America must inevitably express its highest form of democracy. When it can be used as an instrument to get people to express themselves, in order that they may build up a bigger and better community life, it will have performed a real service to society. When the people who live in the small community and the country awaken to the possibilities which lie hidden in themselves through the impulse of a vitalized drama, they will not only be less eager to move to centers of population, but will also be a force in attracting city folks to dwell in the country. The monotony of country existence will change into a newer and broader life.

If The Little Country Theater can inspire people in country districts to do bigger things in order that they may find themselves, it will have performed its function. It is the Heart of a Prairie, dedicated to the expression of the emotions of country people everywhere and in all ages.

People are more or less influenced by their emotions. What matters is not so much what persons think about certain things as how they feel toward them. Thought and emotion usually go hand in hand. One is essential to the other. It is through the heart of a people that emotions are expressed. For centuries the drama has been the great heart strength through which humanity expresses its higher and finer instincts. Its power to sway the feelings of mankind by seeking to find out the hidden life forces in us all can never be overestimated. It is through the drama that people learn to interpret human nature, its weakness and its strength. The sad and the happy, the rich and the poor, the strong and the weak, the young and the old, those with many different ideas and ideals see their actions reflected in this mirror. The supreme duty of[62] society is to point out the way to its citizens, whether they live in the country or in the city, to live happy and useful lives. In this respect the drama plays an important rôle. As Victor Hugo once said, “The theater is a crucible of civilization. It is a place of human communion. It is in the theater that the public soul is formed.”

In the early generations of the world it was the only form of human worship. The Shepherds of the Nile conceived a sacred play in which the character “the God of the Overflow” foretold by means of dramatic expression the period of the flooding of the valley. The Vedic poets sang their songs in the land of the Five Rivers of India. The Hebrews expressed their religious philosophy through a democratic festival called the Feast of Tabernacles. The country people who made Rome their center celebrated the ingathering of their food with a festival called the Cerealia. The Festival of Demeter was a characteristic play of the early Greeks. The country people of the Orient had ritualistic dramas dealing with animal and plant life. The Incas, the Indians of Peru,[63] worshiped at the Altars of Corn. In the realm of nature, Ceres, the goddess of grains, Mother Earth, Pomona, the goddess of fruits, Persephone, emblematical of the vegetable world, Flora, the goddess of flowers, Apollo, the sun god, and Neptune the god of water, have been the theme of many a dramatic story. All these ceremonies and many more not only signify the wide usage of this art in every age and every part of the world, but also unfold tremendous possibilities for future pageant, play, and pantomime among country people. If civilization’s sense of appreciation could be aroused to see the hidden beauties of field and forest and stream—of God’s great out of doors—men and women and children would flock to the countryside. The drama is one of the many agencies which seeks to stimulate this sense of appreciation. It deals with human problems by means of appeals to the emotions.

The absence of a vision in many country communities has been one of the chief causes for their backwardness, their dullness, and their monotony. When the country develops a robust social mind, one that appeals because of[64] the bigness of the theme, it is then that life in the open and on the soil will become attractive. The lure of the white way will pass like ships at night. That a new light seems to be breaking is evidenced by the establishment of consolidated schools, community buildings, and country parks. These and other social institutions, together with better means of communication and transportation, materially assist in the solution of the country life problems. A country district must be active and not passive if it would interest the young and even the old.

If the drama can serve as just one of the mediums to get the millions of country people here and elsewhere to express themselves in order that they may find themselves there is no telling what big things will happen in the generations to come. If, as has often been said, agriculture is the mother of civilization, then every energy of a people and every agency dramatic and otherwise, should be bent to make that life eventful and interesting from every angle. The function of The Little Country Theater is to reveal the inner life of the country community in all its color and romance,[65] especially in its relation to the solution of the problems in country life. It aims to interpret the life of the people of the state, which is the life of genuine American country folks.

While still in its infancy, the work of The Little Country Theater has already more than justified its existence. It has produced many festivals, pageants, and plays and has been the source of inspiration to scores of country communities. One group of young people from various sections of the state, representing five different nationalities, Scotch, Irish, English, Norwegian, and Swede, successfully staged “The Fatal Message,” a one-act comedy by John Kendrick Bangs. Another cast of characters from the country presented “Cherry Tree Farm,” an English comedy, in a most acceptable manner. An illustration to demonstrate that a home talent play is a dynamic force in helping people find themselves was afforded in the production of “The Country Life Minstrels” by an organization[70] of young men coming entirely from the country districts. The story reads like a fairy tale. The club decided to give a minstrel show. At the first rehearsal nobody possessed any talent, except one young man. He could clog. At the second rehearsal, a tenor and a mandolin player were discovered. At the third, several other good voices were found, a quartet and a twelve piece band were organized. When the show was presented, twenty-eight different young men furnished a variety of acts equal to a first class professional company. They all did something and entered into the entertainment with a splendid spirit. “Leonarda,” a play by Björnstjerne Björnson with Norwegian music between acts, made an excellent impression.

A Farm Home Scene in Iceland Thirty Years Ago

Perhaps the most interesting incident that has occurred in connection with the work in this country life laboratory was the staging of a tableau, “A Farm Home Scene in Iceland Thirty Years Ago,” by twenty young men and women of Icelandic descent whose homes are in the country districts of North Dakota. The tableau was very effective. The scene represented[71] an interior sitting room of an Icelandic home. The walls were whitewashed. In the rear of the room was a fireplace. The old grandfather was seated in an armchair near the fireplace reading a story in the Icelandic language. About the room were several young ladies dressed in Icelandic costumes busily engaged in spinning yarn and knitting, a favorite pastime in their home. On a chair at the right was a young man with a violin, playing selections by an Icelandic composer. Through the small windows rays of light representing the midnight sun and the northern lights were thrown. Every detail of their home life was carried out, even to the serving of coffee with lumps of sugar. Just before the curtain fell, twenty young people, all of Icelandic descent, joined in singing the national Icelandic song, which has the same tune as “America.” The effect of the tableau was tremendous. It served as a force in portraying the life of one of the many nationalities represented in the state.

When “The Servant in the House” by Charles Rann Kennedy was presented, it was[72] doubtful in my mind whether a better Manson and Mary ever played the parts. Both the persons who took the characters were country born. Their interpretation was superb, their acting exceptional. In fact, all the characters were well done. Three crowded houses greeted the play.

An alert and aggressive young man from one part of the state who witnessed several productions in the theater one winter was instrumental in staging a home talent play in the empty hayloft of a large barn during the summer months. The stage was made of barn floor planks. The draw curtain was an old, rain-washed binder cover. Ten barn lanterns hung on a piece of fence wire furnished the border lights. Branches of trees were used for a background on the stage. Planks resting on old boxes and saw-horses were made into seats. A Victrola served as an orchestra. About a hundred and fifty people were in attendance at the play. The folks evidently liked the play, for they gave the proceeds to a baseball team.

Scene—“Leonarda” By Björnstjerne Björnson

Every fall harvest festivals are given in different[73] sections of the state, with the sole purpose of showing the splendid dramatic possibilities in the field of agriculture. A feature in one given a few years ago is deserving of special mention. Country people in North Dakota raise wheat. The state is often called the bread basket of the world. A disease called black rust often infests the crop and causes the loss of many bushels. In order to depict the danger of this disease, a pantomime called “The Quarrel Scene between Black Rust and Wheat” was worked out. The character representing Wheat was taken by a beautiful fair-haired girl dressed in yellow, with a miniature sheaf of grain tucked in her belt. The costume worn by Black Rust was coal-colored cambric. The face was made up to symbolize death. Wheat entered and, free from care, moved gracefully around. Black Rust stealthily crept in, pursued and threatened to destroy Wheat. Just about the time Wheat was ready to succumb, Science came to the rescue and drove Black Rust away. Wheat triumphed. Several thousand people saw this wonderful story unfolded in the various places where it[74] was presented. Everybody caught the significance of it at once.

Just the other day a farmer from Divide County who had planned a consolidated schoolhouse came to the theater, in order to find out how to install a stage “so the people in his community could enjoy themselves” as he put it. Divide County is some three hundred miles from The Little Country Theater.

One young man from the northwestern part of the state wrote me a letter well worth reading. He said in part:

“Dear Sir:—I thought you might like to know how we came out on the play ‘Back to the Farm,’ so I am writing to tell you of the success we had.

“In the first place we had a director-general who didn’t believe in doing things by halves. For nearly a month we rehearsed three times a week. That means after the day’s work was done we ate a hasty supper, hurried through the chores, cranked up the Ford and ‘beat it’ to rehearsal. And when we did give it we didn’t waste our efforts in a little schoolhouse with a stage consisting of a carpet on the floor and a sheet hung on a wire for the curtain. Nix! We had an outfit that any theater in a fair sized town might well be proud of.

“Well, we had a full house and then some, they even came from Minot fifty miles north of here and from other neighboring towns. After it was over we got all kinds of press notices, nice complimentary ones, too. Our fame even went as far as Washburn and the County Supt. of Schools asked us to come down and give it at the Teachers’ Institute, Nov. 4, to give the teachers an idea what could be done in other communities y’see? We didn’t go though, didn’t have any way to pay expenses as he wanted to give it free. However, we went to Garrison, Ryder, Parshall, Makoti and drew a full house every time except once and that was due to insufficient advertising, only two days. We collected enough money to buy chairs and other furnishings for our new ‘Little Country Theater’ and also the salary of an instructor to our orchestra we are just starting.

“Our stage is surely ‘great.’ The wings, interior set and arch are made of beaver board, with frames of scantling, the frame of the arch, however, is not scantling, but two by fours. It is all made in such a manner that it can be knocked down and packed away, when we wish to use the building for basketball or other games. The back drop is the most beautiful landscape I have ever seen, a real work of art.

“The front drop curtain is what made it possible for us to get the entire outfit. It has the ad of nearly every business man in Ryder[76] and represents something like $240. The complete stage cost us $200 so we still had some left over.

“The theater which is not yet completed is in the basement of the new brick consolidated school. It will be steam heated and later electric lighted, two dressing rooms back of the stage, and well I guess that’s enough for a while. The auditorium will be about 19 x 40 ft.

“Now I believe what we can do others can do as we are only an ordinary community, our director was a college graduate with a lot of pep and push, that’s all.

“Do you ever loan out any of your scenery? Another party who has ‘caught the fever,’ is going to try the same stunt with modifications. I am getting to be a sort of an unofficial agent for your Extension Div. as people here are getting interested in these ‘doin’s’ so don’t be surprised if you get a letter from us now and then.

“Yours truly,

“A. R.”

When “The Little Red Mare,” a one-act farce was given, Hugh’s father came down to see me and tell me that if there was anything needed in the country it was more life and good entertainments for the young people. He was[77] a very interesting character and a bit philosophical. When I told him about the mistakes made in the work, he pulled out a lead pencil, placed it between his fat thumb and finger and looking straight at me said, “if it wasn’t for mistakes we’d never have rubbers on the ends of our pencils.” His son, Hugh, who took the character of the old deaf fellow in the play, did a superb piece of acting.

Over in the village of Amenia they have a country theater. It is located on the second floor up over a country store, and has a seating capacity of about one hundred and seventy-five people. The stage is medium size. The curtain is a green draw curtain. The lighting system is unique, containing border lights, foot lights, house lights, and a dimmer. The plays selected and produced are only the best. One villager said he never thought plays would change the spirit of the community so much.

Scene—“The Servant in the House” By Charles Rann Kennedy

Up near Kensal, North Dakota, about four miles out from the town, the McKinley Farmers’ Club have a place modeled in some ways after The Little Country Theater. The country people formed a hall association, sold[78] stock to the extent of three thousand dollars, donated their labor, and put up the building. The site was given by a country merchant. It is a typical rural center, consisting of auditorium, stage, rest rooms, dining room, and kitchen. An excellent description of its activities is contained in a letter from one of its members dated April 17, 1918, which I shall quote in part:

“The club year, just closed has been satisfactory in all events. From a social standpoint, this community through the efforts of the McKinley Club has enjoyed the fellowship of their neighbors and friends in a manner that is foreign to most rural communities.

“The officials of the past year have injected literary work into its meetings or rather at the close of the club meeting. Meetings are held on the second and fourth Saturday evenings of each month. The men of the club meet in the auditorium and transact regular business while the Ladies’ Aid of the Club meet in the dining rooms. At the close of the business session all congregate in the auditorium where a program made up of songs, recitations, readings, essays, debates, dialogues, monologues, the club journal, four minute speeches, etc., is given. With the program or literary over, all retire to the dining rooms, where the ladies have a lunch arranged[79] which is always looked forward to. Home talent plays and public speakers are from time to time in order and always enjoyed. A five piece orchestra composed from amongst the membership play for dances, at plays, etc. The dramatic talent of the club has just played ‘A Noble Outcast’ and despite a rainy evening the proceeds counted up to $93.00. The proceeds were used to pay for the inclosing of the stage and stage scenery. They will put this on again, the proceeds to go to buy tobacco for the boys ‘Over There.’ Last June the club members and their families in autos made a booster trip boosting the play ‘Back to the Farm,’ presented by The Little Country Theater Players. They canvassed ten towns in a single day, driving one hundred and twenty miles. The result was that when the ticket force checked up $225.00 had been realized. The club celebrates its anniversary in June of each year.

“The Ladies’ Aid of the club have been a great help and their presence always appreciated. To date they have paid for out of their funds, and installed in the club hall, a lighting system that is ornamental and is of the best, a piano, kitchen range, and a full set of dishes with the club monogram in gold letters inscribed on each piece.

“The stage is enclosed and scenery in place so that the dramatic talent of the community have an ideal place for work.

“I have in a hurried manner given you some of our doings in general.

“Respectfully,

“J. S. J.”

I shall never forget the night referred to in the above letter when “Back to the Farm” was given in the hall. Automobiles loaded with people came from miles around. The hall was packed. Children were seated on the floor close up to the stage. Fifty persons occupied a long impromptu plank bench in the center aisle, with their bodies facing one way and their heads looking toward the stage. They stood on chairs in the vestibule at the back. The windows were full of people. Three men paid fifty cents each to stand on a ladder and watch the play through the window near the stage. It was as enthusiastic and appreciative a crowd as ever witnessed a play. They still talk about it, too.

One of the most artistic pieces of work ever done in the Theater was the part of “Babbie” in Barrie’s play “The Little Minister.” The charming young lady who took the character seemed, as the folks say, “to be born for it.”[81] “Little Women” a dramatization of Louisa Alcott’s book was also cleverly acted.

A group of twenty young men and women from fifteen different communities dramatized “The Grand Prairie Community School Building” project in five scenes. The first scene told the story of the organization of the Grand Prairie Farmers’ Club in the old one-room country school, and the endorsement of the new structure. The second showed the plans and specifications of the proposed building, by means of an illustrated lecture given in the old town hall. In the third and fourth parts the basement with the installation of the lighting system and the preparation of the lunch in the kitchen for the visitors were portrayed. The last scene displayed the auditorium and stage in the community school building complete, together with the dedication ceremonies. The scenery, properties, curtains, and lighting effects were arranged by these young men and women. The two hundred people who saw this dramatic demonstration will never forget the effect it had upon them. It proved that any community which is farsighted enough can with[82] imagination and organization erect a similar structure or remodel a village hall so the people can have a place to express themselves. The essentials are an assembly room and a stage, that’s all.

Scene—“Back to the Farm” By Mereline Shumway

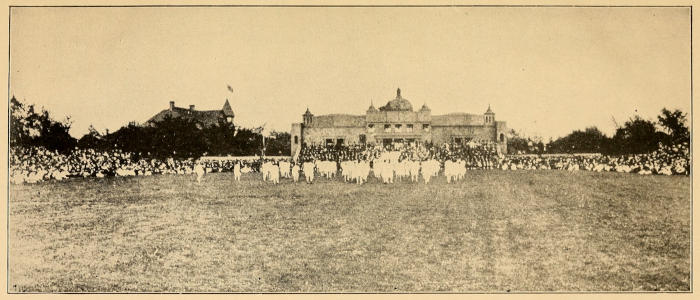

Three outdoor spectacles, “The Pastimes of the Ages,” “The Enchantment of Spring,” and “The Master Builder” revealed the infinite possibilities of the drama in picturing “tongues in trees, books in running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything.” All of these pageants and many more aim to teach the people who live in God’s gardens to appreciate their surroundings. “The Pastimes of the Ages,” as well as the other two outdoor plays, was presented on a flat prairie, a parade ground about three or four hundred feet from The Little Country Theater. Over fifteen thousand people saw the spectacle and twelve hundred people took part in it. The scene was a most impressive one. At one end of the natural outdoor amphitheater the silent sphinx and three pyramids rose in all their Oriental grandeur. At the other stood a temple of glittering gold, in which the Spirit of Mirth reigned supreme.[83] The play opened with Mirth running out of the temple singing and dancing. In the distance she saw a caravan approaching the pyramids. She beckoned them to come forward. The grand procession followed. On entering the temple the sojourners were greeted by flower maidens. Mirth then bade the caravan to be seated on the steps of marble and witness some of “The Pastimes of the Ages.” The Greek games were played. An Egyptian ballet was danced. Forty maidens clad in robes of purple with hands stretched heavenward chanted a prayer. Two hundred uniformed Arabs drilled. The chimes rang. Mirth gestured for all to rise and sing. The bands en masse struck the notes of that song immortal, written by Francis Scott Key. The caravan, having seen all the pastimes in which men and women have indulged in ages gone by, journeyed back to the place from whence it came. And the story of the most gorgeous spectacle ever seen, on the Dacotah prairie ended.

“The Enchantment of Spring” was a pageant in two episodes, with its theme taken from the field of agriculture. The setting was[84] The Temple of Ceres. The Herald of Spring came to the temple with Neptune the God of Water, Mother Earth, Growth, Apollo the God of the Sun, Persephone emblematical of the vegetable world, Demeter the Goddess of Grains, Flora the Goddess of Flowers, and Pomona the Goddess of Fruits, to announce the approach of Spring. The trumpeters signaled the coming of the east and west and north and south winds. They met, they quarreled and Fate drove the north wind away. The three winds then counseled with Neptune, Apollo, and Mother Earth, companions of Growth, as to her whereabouts. They finally discovered Growth at work and bade her to go to the temple. The welcome and the rejoicing followed. At the entry of Spring, the flowers awoke. Ceres called to Spring to come to the steps of the temple. The Crowning of Spring ended the pageant. When it was produced, it opened up the vision of many people as to the latent possibilities of the drama in the vocation of agriculture.

Festival—“The Pastimes of the Ages.” By Alfred Arnold. Parade Grounds, North Dakota Agricultural College, Fargo, North Dakota