The Project Gutenberg eBook of Memories of the Civil War, by Henry B. James

Title: Memories of the Civil War

Author: Henry B. James

Release Date: August 10, 2022 [eBook #68723]

Language: English

Produced by: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Fraternally Yours,

Henry B. James.

BY

Henry B. James.

Co. B, 32nd Mass. Volunteers.

Co. B, 32nd Mass. Volunteers.

NEW BEDFORD, MASS.

FRANKLIN E. JAMES.

1898

To my Boys,

Who delighted in their childhood

to hear their father tell stories of

the war, and at whose desire these

memories have been recalled, this

book is

—DEDICATED.—

| CHAP. | PAGE. | |

| I | ENLISTMENT | 1 |

| II | TO THE SEAT OF WAR | 6 |

| III | ON THE MARCH | 10 |

| IV | ANTIETAM | 14 |

| V | UNDER ARREST | 17 |

| VI | IN CAMP | 21 |

| VII | FREDERICKSBURG | 25 |

| VIII | CHANCELLORSVILLE | 29 |

| IX | BRANDY STATION & ALDIE | 33 |

| X | GETTYSBURG | 38 |

| XI | MINE RUN | 44 |

| XII | A LETTER FROM THE FRONT | 48 |

| XIII | RE-ENLISTED | 52 |

| XIV | AT HOME AGAIN | 55 |

| XV | IN THE WILDERNESS | 59 |

| XVI | LAUREL HILL | 63 |

| XVII | WILDERNESS CAMPAIGN | 69 |

| XVIII | LEAVES FROM MY DIARY | 73 |

| XIX | COLD HARBOR | 79 |

| XX | NORFOLK RAILROAD | 85 |

| XXI | EXTRACTS FROM MY DIARY | 88 |

| XXII | PETERSBURG | 92 |

| XXIII | PEEBLE’S FARM | 97 |

| XXIV | WELDON RAILROAD | 101 |

| XXV | HATCHER’S RUN | 106 |

| XXVI | ON FURLOUGH | 112 |

| XXVII | WOUNDED | 117 |

| XXVIII | CLOSING SCENES | 123 |

| XXIX | MUSTERED OUT | 128 |

I have written this account of my experience in the service of my country from memory, aided by old diaries, letters, etc., and have endeavored to be as accurate as possible, in regard to dates and events of historical importance, but if mistakes occur, it cannot be wondered at, after such a lapse of time. Some of my diaries were lost upon the battlefield, and of those that remain, many of the entries were in pencil and are almost effaced.

I had no intention when I began writing of making a long story, but as I went on, memory brought back many a stirring scene, many a weary march, many a tender thought of comrades who shared them all with me, and so I have written them down as they came to me.

My thanks are due my wife for so carefully editing, and my son for printing my attempt to keep in a permanent form, my recollections of the War of the Rebellion.

I have often been asked to narrate my experience in the War of the Rebellion, and have as often refused, but now after the lapse of thirty three years since the close of that fearful struggle between brother men, I feel that perhaps it would be well, for the satisfaction of those who so earnestly desire it, to “Fight my battles over again.”

Mine was not an exceptional experience, only that of many a boy of ’61, but it may[2] partly answer the question so often asked: “What did the privates do?”

I have often wondered how it happened that I, born of quaker stock on my mother’s side (she was descended from the Kemptons, who were among the first settlers of our quaker city of New Bedford,) should have had such a natural leaning towards scenes of adventure and conflict. It may well have been that I inherited it from the paternal side of the house, for my father’s father, John James, was taken prisoner on board his ship during the War of 1812, and thrown into an English prison, and I have often, during my childhood, listened to his tales of warfare and bloodshed, and longed to be a man that I might fight and avenge the wrongs inflicted on my devoted country in its earlier days; and how I wished, as I read of the War of the Revolution, that I might have lived in those stirring days, and done my part in creating the American Nation.

Certainly it did not seem possible that occasion would ever arise when I should be one of the defenders of that great nation.

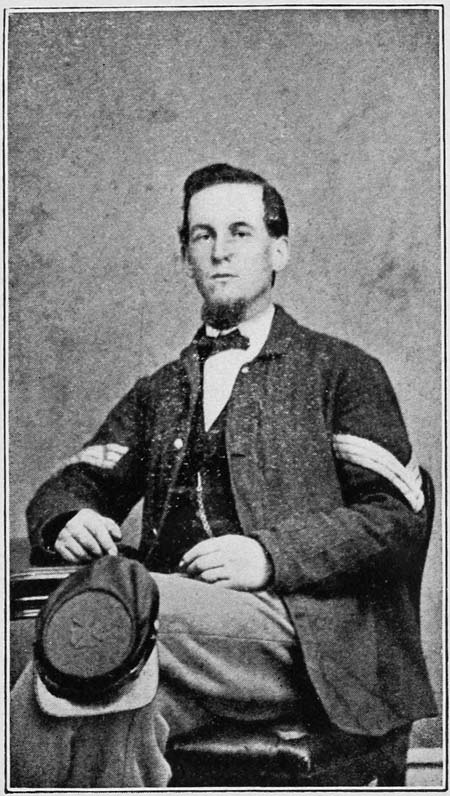

The attack on Fort Sumter, the shot that so stirred the loyal hearts of the men of the North, awakened in me an ardent desire to enlist[3] and help avenge the insult to our country’s flag, but my father was so opposed to the idea that I reluctantly yielded to his authority until a few months later, during a visit to my brother in Woburn, Mass., I enlisted November 2nd 1861, just past my twentieth birthday, in Co. B, 1st Battalion, afterwards the 32nd Mass. Infantry. The company was raised by George L. Prescott, of Concord, Mass.

We were mustered into the United States service on November 27th, and on December 3rd were sent to Fort Warren, Boston harbor, to guard prisoners of war, among them being the confederate generals Buckner and Tilghman, Commodore Barron, Colonel Pegram, the confederate commissioners Mason and Slidell, the mayor and chief of police of Baltimore, and many others.

I remember an incident that may be of interest to which I was an eye-witness: General Buckner was walking on the parapet, under guard, when a foreign man of war was being saluted in accordance with military usage; a large 32 lb. gun was belching forth half minute salutes; as he drew near it, wrapped in deep thought, not seeming to notice what was taking[4] place the order came to fire just as he was abreast of the gun; he realized his danger and jumped forward just in time, for the next instant the gun was discharged, and the prisoner must have felt that it was indeed a narrow escape.

Many other interesting incidents connected with these celebrated prisoners occur to me, but they would make my story too long.

We were drilled in the art of war during all that winter, and under the strictest military discipline, the commander of the fort being that brave old martinet of the regular army, Colonel Justin E. Dimmock. My brother George also enlisted in the same company as myself and was with me at Fort Warren, but the hardships and exposures of that long cold winter and an attack of typhoid fever undermined his health to such an extent that he was discharged a short time before we left Fort Warren for the seat of war in the following May.

The hard and laborious life of the army seemed to agree with me, and from the day of my enlistment until the time I was wounded, more than three years later, my health was perfect, which was something to be thankful for, in the army.

[5]I did not regret leaving my brother behind me for I felt that one son was enough for my father to spare for his country’s service; besides my brother had a wife and child, while I was young, with no mother to mourn for me, should I fall, and I felt that I could be spared better than those who had home ties, and that I could face hardships and dangers better than those who had families depending upon them. In short it seemed my duty and pleasure to go to the war.

On the 25th of May we left Fort Warren for the seat of war. Arriving at Washington we went into camp Alexander. June 30th our battalion, now composed of six companies, was ordered to join the army on the peninsula. Embarking on the transport Hero we arrived at Fortress Munroe July 2nd.

We continued on up the James river, landing at what was formerly President Harrison’s plantation, on July 4th 1862. Now began[7] our soldier life in earnest, for fighting was then going on; mud was knee deep and all was confusion. We were assigned to the brigade of Gen. Charles Griffin, division of Gen. Morell, in Fitz John Porter’s command, afterwards the Fifth Army Corps.

We were drawn up in line and given 80 rounds of ammunition. Just then an officer rode up covered with mud, and said: “Well boys, I will give you a chance at the rebs; keep cool and fire low!” Off he went, and I was informed it was Gen. George B. McClellan.

We moved through a piece of woods, and were opened upon by a battery. It was getting to be pretty warm, when the order came “Forward to charge the battery,” but before we could move, the order was countermanded, and we retreated; this was the end of the Seven Days Fight.

We camped upon the banks of the river and staid there six weeks, every day sickness and death reducing our ranks, for it was a very unhealthy place. In fact it was the worst place that could be imagined for a camp, marshy, wet ground, dust and mud alternating; what wonder is it that our men sickened and died? Here on August 9th Lieut. Nathaniel French Jr., one of[8] the most promising officers in our regiment died of malarial fever.

Through it all my health remained perfect, and I was always ready for duty. Many of our regiment were here detailed to act as guards over the quartermaster’s stores on the river bank.

Soon after our arrival at Harrison’s Landing, President Lincoln visited and reviewed our army. Our division stood in line from four o’clock in the afternoon until after nine in the evening, and then a party rode by in the moonlight, one of whom was said to be the President of the United States; as he was the only one who wore a stove-pipe hat, we concluded that it must be a fact, that we had been duly reviewed, and gladly broke ranks and prepared our suppers.

On the night of August 1st the enemy ran six pieces of artillery down on the opposite side of the James river, and about midnight opened upon our camp, and cold iron rained upon us, ending our slumbers for that night. We had two tents for the officers, and five for the men, and solid shot went through them all, but we escaped serious injury, which seemed rather remarkable. We were more than eager to leave[9] this sickly camp and life of inaction, but here we had to stay and wait for marching orders.

Marching orders came on August 10th, and we gladly took up our line of march, passing through Williamsburg, Yorktown and Big Bethel to Newport News, where we boarded steamer Belvidere for Acquia Creek, thence by rail to Stafford Courthouse, near Fredericksburg. We were still kept on the move, and on August 27th we marched out on the Gainesville road, and[11] formed in line of battle; here we had quite a sharp brush with the enemy. We were endeavoring to head him off in his march northward, but were too late, and had to chase him as rapidly as possible.

March 6, 1865.

I shall never forget the long and weary march of the next day, which happened to be my twenty-first birthday. All that hot, dusty day was spent in a forced march, and we suffered greatly for water, of which there was none to be had in that dreary country. Along in the afternoon I came to a puddle of water covered with green slime, in which partly lay a dead mule, who had probably died while trying to slake his thirst. I did not take warning by him, but brushed aside the green scum and took a drink; it was wet and that was all that could be said of it.

I dragged myself along until within an hour of sunset, and then I dropped by the roadside as hundreds had done before me. Our surgeon came along, and kindly urged me to keep on, saying we were to camp in a piece of woods about a mile further on; but I was too far gone to stir then. I rested an hour or so, and then limped into camp; too weary to get anything to[12] eat or drink, I took off my equipments and without even unrolling my blanket, dropped upon the ground, and with my knapsack for a pillow, slept all night the dreamless sleep of a tired soldier.

When the boys reached camp, their first thought was to find water; there was but one well in the vicinity, and that was found under guard reserved for the headquarters mess. The indignant rank and file drove off the guard and helped themselves to the water.

Some of the boys, not knowing of the well, went into the swamp and dipped up the stagnant water there. No wonder there was a large amount of sickness after that time. It did not make me sick, but I felt rather lame when I awoke in the morning.

Next day, August 29th, we arrived on the old battle ground of Bull Run, in time to take part in the second battle of Bull Run. Again we had to fall back, and again we took up the line of march.

The next day we moved at 3 o’clock A. M. and camped at 11 P. M., after a march of twenty eight miles. At Chantilla we met the enemy on September 1st, but after a short engagement again kept on, marching through Georgetown into[13] the state of Maryland. It was hot weather, and many of the men fell exhausted by the way; but we must not pause, for the enemy was still pressing northward and we must get between him and our own loved homes.

When we reached the South Mountain battle ground, that fierce conflict was over and they were burying the dead. I saw the body of General Reno who was killed in that battle. We had won a victory, but the loss was very heavy, and we had lost the gallant Reno, a serious blow for our cause. The idol of his men, they greatly mourned his loss.

Harper’s Ferry had fallen, and Lee was gathering his army on the west bank of Antietam Creek in Maryland. When we reached the east side of the creek, we caught up to the main army under General McClellan on the 16th of September, just at sunset. We found the rebels[15] to be well posted behind the top of the ridge on the other side of the stream.

The two armies now stood face to face, for McClellan’s army was camped on the east side of the hills on the west branch of the Antietam. Our division was soon among them, and busy getting our supper, while we could see the smoke from the campfires of the opposing forces, where they too were preparing their evening meal.

What a beautiful sight it was after nightfall! The thousands of glowing campfires upon both hillsides made a picture upon my memory that time will never efface. After our weary march it seemed good to be here in camp, even though I knew a battle was to be expected the next day. I remember how peaceful and quiet everything seemed, and the cheerfulness of the men around me, showed how they enjoyed the welcome rest, and how little they thought of the conflict before them.

The 17th of September dawned fair and pleasant, but what a storm of death took place that day! The battle began at dawn and lasted until dark. The loss of life was terrible; the loss to the Union army alone was more than fifteen[16] thousand men. We held the field, but on that narrow strip of ground between the Potomac river and Antietam Creek lay many thousands of brave men, while their comrades were so worn out with their terrible exertions that they could hardly find strength to care for the wounded or bury the dead.

Our regiment being on the reserve, supporting a battery, our loss was not heavy. On the 18th our corps relieved the ninth (Burnside’s) corps at the lower bridge. On the 19th we expected another battle, but the enemy had retreated during the night. We pursued them through Sharpsburg, capturing many prisoners and several pieces of artillery. We went into camp and excepting a two days raid to Leestown, remained quiet until October 30th, when we started for Harper’s Ferry and crossed the river into Virginia once more.

My company was detailed to guard the ammunition train on its way back into Virginia. Before starting on the march, we had general orders read to us, forbidding all foraging in Maryland. On the first day’s march towards[18] Harper’s Ferry, several of the boys, myself included, noticed a number of small pigs in a field near the road.

As we had been on very short rations for about a week, it seemed to us a good chance to have a feast when we went into camp, so over the fence after the pigs we went. As I raised my gun to fire at a pig, I saw General Griffin, (who commanded our brigade,) and his staff, passing along the road on the further side of the wagons.

I waited until I thought he was beyond the sound of my rifle and then fired. The bullet passed through the pig, struck a stone, glanced, and went down the road, passing within a foot of the general’s head, for he had stopped for a few moments, instead of riding on as I had supposed.

After I had shot the pig, one of the boys ran up and was using the butt of his gun to finish him and stop his squealing, when suddenly we were surrounded by the staff of Gen. Griffin! I made a break for the road, but found it was of no use, for the general himself stood by the fence, so back I went and with the rest of the boys was placed under arrest. Orders were given to march[19] us to camp without rest, and carry the pig along, which we took turns in doing. It was a long pull, and when I could march no longer, down I sat. The guard repeated the order. “I am going to rest,” I said. “Don’t let the general see you,” said the guard.

I did not rest long, but traveled all day without anything to eat, for we had left our haversacks and overcoats in the teams, which were now a long distance ahead.

At night we went into camp, then had to dress the pig, and it was cooked for the supper of the general and his staff, and we poor fellows got nothing. We pitched the general’s tent and were then turned over to the provost guard. About eight o’clock I went under guard to the general’s tent to do something he wanted done. “Guard, to your quarters,” said the general, “This man will not run away!” “No, general, I will not,” said I, and I quickly performed the duty required of me and went back to the provost guard.

At ten o’clock we were all sent under guard to our regimental headquarters. Our colonel had just rolled himself up in his blanket for the night and did not care to be disturbed. “Do[20] you know where your company is?” he demanded:

“Yes sir” we answered, without any regard for facts.

“Go to it,” he ordered, and we gladly started, free men once more. There were one hundred thousand men in the camp, and to find one small company in the middle of the night was no easy task, but about daylight we found the teams and our haversacks, got something to eat, and started off on the march again. So ended the only time in my life that I was a prisoner, or under arrest.

The Army of the Potomac, on November 10th, 1862, was massed near Warrington Virginia, where General McClellan was relieved from command of the army. I shall never forget the grief that was manifested by the soldiers on the removal of this popular commander. Ever mindful of the welfare and comfort of his men, he had won a warm place in their hearts, and enjoyed[22] the respect and esteem that was never accorded any other commander.

The following verses were sung in camp and on the march long after he left us:

[23]He was succeeded by General Burnside, and after a week of rest, we started for Falmouth Virginia, and on the 22nd went into camp at Stoneman’s Switch. Here we remained most of the time all winter, although we expected every day to be ordered off on the march again for the unknown “Somewhere.”

I well remember the hungry Thanksgiving day spent here. We were a long ways from our base of supplies at Acquia Creek, and all that we received was brought in wagons for several miles over hard and rough roads from Belle Plain.

For a week we lived on hardtack, and the morning of Thanksgiving day, we received the last of the supplies in our regiment, half a cracker for each man. This was all we had until afternoon; our officers were out all the morning hunting in every direction for food, and at last succeeded in borrowing twenty boxes of hard bread, which was all that the officers and men had that day.

How we thought of home that day and the good dinners that we had enjoyed on former festival days! How little our friends at home would have enjoyed their feast, could they have[24] known that we were starving! In the course of the day I happened to see, near the tent where the officers bought their supplies, (for they did not draw rations like the rank and file,) a few beans that had been trodden down into the mud. I carefully picked them out, and perhaps got half a pint altogether, which I washed and stewed, and with my tentmate, made out our Thanksgiving dinner.

This was not the only time I have gone hungry; many a time have I suffered from hunger from cold, and from heat, but I shall ever remember that particular time, for it seemed to make me still more hungry as I thought of former Thanksgiving feasts, and the food I had wasted. But such are the fortunes of war, and we bore it as we did all other discomforts, as part of the price that must be paid, that our flag might again wave over an undivided country.

Here we remained for some weeks, building ourselves log shanties, chopping wood, standing guard, being drilled, inspected, reviewed, and now and then going over towards the river and watching the confederates making their works good and strong, against the time when we were ready to attack them. While we were making ready, they were building and strengthening[26] works, that would be beyond the power of mortal man to carry by assault, and yet that was what we were called upon to do, when at last General Burnside had got his army ready for active service. He had entirely re-organized the Army of the Potomac, which now numbered one hundred and twenty thousand men, divided into three grand divisions, each division consisting of two corps. Everything possible was done to strengthen our forces, and put us in good condition for active service; all this was not completed until the 11th of September.

The town of Fredericksburg is on the south side of the Rappahannock river, nearly opposite Falmouth. Back of the town is the range of hills called Marye’s Heights, where Lee’s army was strongly entrenched, when Gen. Burnside had got ready for business.

General Lee, with his three hundred cannon, covered the town and river, and his position was one of the strongest, yet Burnside persisted in his plan of attack, for on the morning of the 11th of December, at daybreak, the bugle sounded “Forward!”

It was a still, cold morning, and we started off in heavy marching order, our regiment[27] leading, as it was our turn that day. We were in good spirits, although we knew that we had started out on a desperate attempt, and were enroute for Fredericksburg, three miles away. We marched to a point near the river and remained until the next day, when we crossed the river on pontoon bridges under a heavy fire from the enemy, with terrible loss of life.

On the 13th the bloody battle of Fredericksburg was begun, one of the most disastrous of the war. It was a useless, ill-judged endeavor to rout Lee’s army from his impregnable position. In this battle more than thirteen thousand men were lost to the Union army, while the confederates lost less than half that number. My regiment lost thirty live men, killed and wounded. Defeated and disheartened, on the morning of the 16th, our army re-crossed the river and returned to our old camp.

On the 21st of January, 1863, we started on the “Mud march,” about four o’clock in the morning. A bitter cold wind was blowing fiercely, and the air was full of sleet and rain. We marched all day and when we stopped for the night, made fires and sat around them all night to keep warm. The next day was warm[28] as summer, but rainy; the mud grew deeper, as we struggled along, sinking in and being pulled out, taking us all day to go three miles. The whole country was under water, and you could not step without sinking above your shoes in mud. When we stopped for the night we could only lay down in the mud, or sit by the fires we managed, with much difficulty, to make.

The next day the water dried up a little, so we pulled down the fences and used the rails to corduroy the road. We returned to Stoneman’s Switch, and re-constructed our shanties as well as we could, though we sadly missed the comforts we had destroyed before starting out, lest, in our absence, they might fall into the hands of the Johnnies.

We remained in camp until spring, and before that time arrived. Gen. Burnside was relieved, and General Hooker took his place. We gladly heard the order read that relieved him and appointed “Fighting Joe” as his successor.

On April 27th 1863, we again started on our tour through Virginia. We crossed the Rappahannock at Kelley’s Ford, marched to the Rapidan river, and went into camp on the south side. A brief rest, and again on the march, arriving at Chancellorsville, where we waged battle with the[30] enemy from April 30th to May 5th. Here, on the 2nd of May, occurred the famous charge of the eighth Pennsylvania cavalry, numbering but three hundred men under Major Keenan, on Stonewall Jackson’s leading division, keeping them back for a short time, giving our generals time to place their guns in position, thus saving our army from utter defeat. The tragic story is told by the poet Lathrop far better than I can tell it.

We were defeated, and obliged to retreat, our brigade being detailed to cover the retreat of our army back over the river. We formed a line of battle, and as each division passed, we fell back a little nearer the river, still keeping our line of battle. Finally we were within half a mile of the river, where the last of our army were rapidly crossing on pontoon bridges. General Griffin, our brigade commander, had crossed the river on some duty assigned him, when he was informed that a large force of the enemy was rapidly approaching, and his brigade would inevitably be taken prisoners.

“If they are, I will be taken with them!” exclaimed our brave commander, and spurring his horse, he rapidly crossed on the pontoons, and[32] soon reached us, and marched us quickly to the river, just as the confederates approached, intent on gobbling us up. We cut the fastenings of the pontoons, and the bridge swung off down the stream just in time, and we were all safely landed on the other shore, happy to know that we had escaped the horrors of a rebel prison, or death at the hands of the merciless foe.

After the battle of Chancellorsville, the thirty-second Massachusetts was detailed for guard duty on the railroad to Acquia Creek. We remained here but a short time however, for northward moved the enemy, and we on after them; at Brandy station on the 9th of June, we caught up with them, and had a sharp engagement, but failed to stop the march into Pennsylvania.[34] Crossing the river towards Culpepper Courthouse, past Morrisville, on to Manassas, camping on the old battle ground on the night of the 16th.

We had a tough march the next day, travelling more than twenty miles; no water was to be had, and we suffered greatly with the heat and dust. Our regiment started in the morning with two hundred and thirty men, and camped that night with one hundred and seven, of which number I was one, and this was doing better than any other regiment in our division. Hundreds of men dropped by the roadside, fainting and dying from exhaustion; four died of sunstroke. We heard indications of battle all day from the direction of Aldie, and I suppose this forced march was thought necessary, but I can truly say that I much preferred all the horrors of the battlefield to these terrible long marches, when it seemed impossible to keep up. To drop out was to lose sight of your regiment, and perhaps die uncared for, or be gobbled up by guerrillas, who were plentiful all through that God forsaken country.

To be captured by guerrillas was sure death or imprisonment, which to me seemed[35] worse than death on the field. It was during this march that I acquired the nickname of “Mosby,” after the noted guerilla Colonel Mosby, who was then making his dashing raids through that region, causing his very name to be a terror to all the inhabitants thereof.

I had picked up from the road where it had been dropped, among other impedimenta by the rebels we were pursuing, a gray cardigan jacket, which, being much better than the one I had worn so long, I had put on, and thrown away the old one. I wore it into the battle of Gettysburg a few days later, and had several narrow escapes from being shot for a rebel by our own men, on account of its color. As it was all I had, I had to wear it, for we could draw no clothing on the march.

Some little time after the Gettysburg fight, I was on guard at the colonel’s tent, and he noticed my gray jacket, and enquired why I wore it, and I told him it was all I had.

“I’ll see that you have another, my boy,” said the colonel, and soon after, my captain provided me with a new blouse, which I gladly donned, discarding the gray one, which had but one fault and that was its color. I could not discard the[36] nickname however, by which I am best remembered by some of my old comrades, who will never forget how I fought the Johnny rebs at Gettysburg, with a confederate’s jacket on.

At Aldie occurred the great cavalry fight under Generals Pleasanton, Gregg and Kilpatrick. What a splendid sight it was! An event even in our eventful life to see those brave men move in battle line, with sabres drawn, steady as though on dress parade! Through the enemy’s line they went, dealing death right and left. Not all of them came back, but those who did, came with victory perched upon their banners.

Then on we went, across the state of Maryland, encamping at midnight July 1st at Hanover, Pennsylvania, after a forced march of sixteen hours. By this time we were about worn out with so much marching and fighting, but there was no rest for us yet; for we had hardly dropped down for the night, when an aid arrived with orders to march directly to the aid of the First corps, which was fighting the whole rebel army at Gettysburg. So again we took up our weary line of march, pressing forward as fast as possible to the aid of our comrades. As we drew near Gettysburg, word passed down the line[37] that General McClellan was again in command of the army.

How we shouted! How we cheered, and we moved on with quickened step, believing that our beloved general would lead us on to battle, and to victory! It was a false report, perhaps sent down the line to cheer our hearts and quicken our lagging feet. It served the purpose, but it was a sad disappointment, when we learned the truth.

We arrived on the field of Gettysburg at nine o’clock A. M., July 2nd, and without rest were ordered into the front line of battle. Our[39] brigade consisted of the 9th and 32nd Massachusetts, 4th Michigan, and 62nd Pennsylvania. We had hardly got into line, when the enemy advanced directly upon us, and for an hour we had it hot and heavy.

Here our regimental loss was heavy, but we finally repulsed them, and soon after changed position to a piece of woods bordering on the wheatfield. Here a line was engaged in the wheatfield, and the ground was covered with the wounded and dead. We advanced and relieved them, when the enemy charged us with such overwhelming fury that we were obliged to fall back.

Here Colonel Jeffers of the 4th Michigan and a color sergeant of the same regiment were killed, trying to save their flag, but it was captured, and a part of the regiment were taken prisoners.

We could not stand the terrible storm of leaden hail, and were retreating when our brigade commander halted us and ordered us to face the charging enemy. It was a fatal act for many of the Thirty-second! We fought our way back inch by inch, union and confederate men inextricably mingled; so we fought until we gained the[40] shelter of the woods. I had lost my regiment, but saw the Pennsylvania Bucktails fixing bayonets for another charge, so I stepped into their ranks to charge with them, when I saw my regimental colors, with four of the color guard near by, so joined them and waited for the boys to rally under the old flag, when we again advanced into the bloody fray.

I look back with pride upon the valor shown that day by my brave comrades; at Little Roundtop, the Wheatfield, in the Loop, many a brave boy of the 32nd gave up his life, in that terrible struggle. Our regiment carried into the fight 227 men, and we lost 81 killed and wounded. My tentmate, Dwight D. Graves, went down severely wounded in the foot, and another comrade, Calvin P. Lawrence, was left on the field with a broken leg when we fell back. As the rebs charged over him, one of them turned to bayonet him, but his lieutenant prevented him, and asked the wounded man,

“Where’s your men now?”

“You just keep on, you’ll find them!” was the reply, as the men swept over him. Soon they rushed back in full retreat, and our brave comrade shouted after them, “I say, leftenant, I[41] guess you found them.” We kept the field, and all that night I spent looking over the battle ground for wounded comrades, giving to one a drink of water from my canteen, placing a knapsack under the head of another, covering another from the chilly air with a blanket picked up on the field, and doing what I could to relieve their suffering.

Morning came, and our brigade remained near Little Round Top, receiving our full share of the storm of iron hail, throughout the artillery duel of the third day. Then came Pickett’s desperate charge, the final effort of the enemy, who never got further north than here. Then came the retreat of the enemy, and our pursuit of them back into Virginia.

During the battle, my cousin, James A. Shepard, of the 18th Massachusetts received his death wound, while going to a spring to fill several canteens for his comrades. I saw him the day before the battle bright and cheerful. I heard he was wounded, but did not learn of his death until some days after, when a letter from home gave me the following account of his death and burial.

He was shot in the shoulder, severing an[42] artery, and died in a Philadelphia hospital a few days after the battle, but lived to see his widowed mother, who was telegraphed for, at his request.

When she arrived at the hospital, she stood a moment at the door of the ward where her boy lay on his deathbed, and where the long rows of beds and their occupants all looked alike to her; she heard his voice at the further end of the room, saying “Oh mother, mother! here I am come quick!” and soon the heartbroken mother knelt by his bedside, while he, happy in her presence, talked of the battle and tried to comfort her.

“I know I’ve got to die,” he said, “But never mind, mother dear, it is in a glorious cause, and we whipped the rebels good!” Poor boy, he was only twenty, yet was willing to die for his country!

As he grew weaker, he talked of the dear ones at home, and wished he could have bade them goodbye.

“Kiss them for me, mother,” he said, “And take me home, and lay me beside my father, and put some flowers on my grave from the dear old home garden, that I have so longed to see!”

[43]His mother remained with him until he died, and through untold difficulties, she brought his body home, being obliged to smuggle it part of the way, and now, in the family lot, he lies beside his father and mother. Two of his brothers also lie buried there, Charles, who served in the Massachusetts heavy artillery, and George, who was badly wounded in the head while serving in the navy; he never fully recovered, and died soon after the war ended.

We crossed the river near Berlin, keeping east of the Blue Ridge. At Manassas Gap on July 23rd, we saw some pretty fighting by the Third Corps, and on the 8th of August, we went into camp at Beverly Ford, and remained five weeks, enjoying our well earned rest. Here I saw five deserters shot. Sept. 15th we moved to Culpepper, where I saw a bounty jumper drummed out of camp, branded with the letter D. Here[45] we received 180 recruits, and between October 10th and 29th, we were marching back and forth, to one point and then another, as though our generals thought we needed exercise.

November 29th, 1863 found us in line of battle at Mine Run. For three days and nights we faced the enemy, and awaited the signal to open the battle. I shall never forget one night, the coldest I ever saw in Virginia. Mine Run was a little stream of water made formidable by the rebels, whose works were back of it. The stream was filled with thorny bushes and brush, now frozen in; when across that, there was a strong abattis made of sharpened timber, that must be removed before we could charge the enemy, strongly entrenched behind earthworks. Not much charging could be done in that situation, and we old soldiers knew the hopelessness of such an attempt.

We knew that the order had been given to charge on the enemy’s works at daybreak. We felt rather gloomy, for we knew that death was certain, if we made that desperate attempt. For my part, I had faced many dangers, had been under fire many times, but had never felt, as I did then, that death stared me in the face. The[46] horrors of that bitter cold night can never be told. All night long we had to keep in motion to avoid freezing to death, for no fire could we have, lest we be discovered by the enemy; more than one poor fellow was frozen to death in the rifle pits.

Morning came at last, but we heard no order to charge. All honor to General Meade, who has been censured for his failure to charge across Mine Run. With all his bravery, he was too humane to order such a useless sacrifice of life, though he knew he incurred censure and probably disgrace, in ordering a retreat instead. Silently we retreated out of our dangerous situation, and made our way towards Stephensburg. Hungry and cold as we were, we hurried along, halting now and then just long enough to build a little fire and boil some coffee, the soldier’s best friend.

Towards night it grew warmer, and when the order came to halt for the night on an open plain, we were too tired to do anything but drop in our tracks, rolled up in our rubber blankets. When we awoke in the morning, we found that several inches of snow had fallen during the night, and covered that vast body of sleeping[47] men as with a white and fleecy blanket. We soon had fires and a warm breakfast. By ten o’clock the snow had melted, and we took up our march with renewed courage.

Our army crossed to the north side of the Rappahannock river, and two days after found us encamped at Liberty, near Bealton Station, on the Orange and Alexandria railroad, and here we had a brief respite from our toils and dangers.

Camp at Liberty Va., Dec.—1863.

You ask me about our daily life, and now, while “All is quiet upon the Potomac,” I will try to give you some idea of company B’s life in camp. Reveille is sounded at sunrise; our company falls into line, and the first sergeant calls the roll.

Each man then cooks his own breakfast, except when two or three tentmates agree to take[49] turns. In my case, my tentmate does the cooking, and I get the wood and water. Our rations when in camp are generally hardtack, pork, salt, sugar, coffee, beans, potatoes, fresh meat, etc., but we do not draw all of these things at once; some days we will draw hardtack and pork, sugar and coffee; on other days, fresh meat, and potatoes.

In drawing rations for the regiment, the quartermaster draws up a requisition for as many rations as there are men in the regiment; they are sent to regimental headquarters, and divided among the companies. The first sergeant of each company receives it, and divides it among the men.

One day’s rations consists of ten hardtack, half a pound of salt pork, a few spoonfuls of coffee, and the same of sugar. In drawing fresh meat, it is cut up into pieces, the orderly calls the roll, beginning one day at A, and the next at Z, and as each man’s name is called, he steps up, takes his choice of the meat, and the last is “Hobson’s choice.”

After breakfast, surgeon’s call is sounded, and if sick or unfit for duty, the boys report to him; he gives them pills or quinine, and reports[50] them either fit for duty, or sick in quarters. His word is law, and if he understands his calling, he seldom makes mistakes; but I have known many instances where men have been reported for duty, who were not fit to be out of their bed.

Next, the orderly makes the detail for camp guard, police, picket, etc. At 8 o’clock A. M., camp guard is placed on duty around the camp, and remains so for twenty-four hours, two hours on post, and four off. Those detailed for police duty, are placed under a non-commissioned officer, and set to cleaning up camp.

The pickets fall in, and after all the details from the various companies get together, they are marched to the front, and are posted so that the whole front is guarded, relieving those that have been on duty. They remain on duty for twenty-four hours, two hours on post, and four off, except when very near the enemy, in an exposed position, then they sometimes remain for several days.

After the pickets go on duty, we who are not detailed for duty, have about two hours to ourselves, in which to wash and mend our clothes, clean our rifles and equipments, etc. At 10.30[51] o’clock we go on company drill, which lasts an hour, after which, we get our dinner.

After dinner we have battalion drill, brigade drill, or something else to keep us busy, and out of mischief.

Dress parade comes at sunset, tattoo at 9 o’clock, taps at 9.30; all lights must then be out, and the army is at rest.

It was at Liberty that most of the members of the 32nd Massachusetts re-enlisted for three years more. I was not the first to re-enlist; I knew now what a soldier’s life really was. I realized that my father knew what he was talking about, when he told me that it was no holiday[53] picnic, and that the men of the South were as brave as those of the North, and that it would take years instead of months to conquer them, as so many thought when the war began. I had endured two years of hardships and dangers, and longed for a peaceful life with those I loved at home. I knew my dear old father would be grieved, were I to again enlist.

I fought it all out alone on picket, that cold long night, went back to camp, and with fingers almost too stiff with cold to hold the pen, signed my name to the paper that bound me to the service of my country for “Three years more, or until the close of the war.”

Yes, I had made up my mind, that come what would, I would see it out! My country needed me; dire disaster had overtaken it, dark and gloomy was the situation, and now more than ever, were needed strong and willing hands to defend it; and so I would do my duty, and leave the rest to God.

And now, looking back over the long years since that day, I can truly say, I have never regretted my decision. The terrible year that followed would have been included in my first term of enlistment of three years, and so I did not[54] serve quite a year longer than I would have done, if I had not re-enlisted. Many a poor fellow who felt that three years was enough, and that he could not endure such a life any longer than that, and consequently did not re-enlist, lost his life in the battle summer that followed. But none could foresee the future, and the close of the war looked to us in the field, as a long way ahead.

So many of the regiment re-enlisted that we were given 30 days furlough, and allowed to go home as a regiment. We had previously had re-enforcements from time to time, so that there were 340 who re-enlisted, and started for home, arriving in Fall River by the New York boat, on January 17th, 1864.

As the day of our arrival was the Sabbath, which we dimly remembered was kept sacred at the North, the commanding officer telegraphed to Governor Andrew to know if it would do to take his men through Boston on the Sabbath day. He quickly received the answer, “Come right along!” So he issued orders to the men to[56] be as orderly as possible, and not shock the pious people of the Puritan state, and we took the train to Boston.

How astonished the war-worn soldiers were at their reception! Ours was the first Massachusetts regiment returning with the proud title of “Veteran,” and the people had turned out en masse to do us honor. We marched through crowded streets to the State House, where we received a welcome from the Governor, and a salute was fired in our honor, on the Common; then to Faneuil Hall, where a most sumptuous dinner was prepared for us, of which we were invited to partake, by the Mayor of Boston.

After dinner, Governor Andrew made an address that will, I think, ever be remembered by the members of the old 32nd. I cannot remember all he said, but some of his eloquent words still linger in my memory:

I cannot, soldiers of the Union Army, by words, in a fitting measure, repeat your praise. This battle-flag, riddled with shot and torn with shell, is more eloquent than human voice, more pathetic than song. This flag tells what you have done, it reveals what you have borne, and it shall be preserved as long as a thread remains, a memorial of your valor and patriotism.

I give you praise from a grateful heart, in behalf of a grateful people, for all you have suffered, and all you have accomplished; and while I welcome you to your homes, where the war-worn soldier may rest a brief while, I do not forget your comrades[57] in arms who have fallen, fighting for that flag, defending the rights and honor of our common country. The humblest soldiers who have given their lives away, will be remembered as long as our country shall preserve its history.

As the people gazed on the torn and blackened remnant of the beautiful silk flag we had borne away with us two years before, it seemed to tell more eloquently than words could do, of battles won and lost. And now, after the lapse of thirty-four years, it still, with other battle flags, is preserved in a glass case in the State House at Boston. If you should look for it there, it might be difficult to find it among the many handsome banners hanging there, for it is a mere strip of silk that seems to be just hanging by a few threads to the staff, a black and ragged remnant of the beautiful silk flag we took with us to the front; but we old soldiers are far more proud of it than we were in the days when it was first presented to us, before it had been consecrated by the blood of the brave boys who bore it through the storm of battle, and gave their lives, rather than the flag should be lost to the regiment. We had a new flag to take back with us, and that also bears the marks of shot and shell, and is sacredly preserved.

After the dinner was over, we were dismissed,[58] and I made quick time to New Bedford, where I received a warm welcome from my father, who was overjoyed to see me.

The first night at home, I went to bed in my old room, but could not sleep, the feather bed was too soft for me; at last I got up, rolled myself in a blanket, and laid down on the floor, where I slept like a top. The feather bed was removed next day, and I slept very comfortably after that on the straw mattress.

How the happy days flew by, when friends vied with each other in making my furlough pleasant for me, and doing their best to spoil my appetite for army rations, with their cakes, pies, and all sorts of good things!

But all too soon we had to say goodbye. On February 17th we once more started for the South, arriving at camp Liberty two days later, warmly welcomed by the comrades we had left there, and proud of the title of “Veteran,” with all that it implied.

General Grant now took command of the army, and on April 30th 1864, we broke camp at Liberty, and began the hardest, most bloody campaign of the war. Our division gathered near Rappahannock Station; crossed the river for the fifteenth time, and marched to Brandy Station, marching almost constantly. We crossed the Rapidan at Germania Ford, marched all the next day, camping at night in the Wilderness, very near the enemy. May 5th we threw up[60] earthworks, but at noon advanced, leaving our works to other troops. We were soon heavily engaged, and so began Bloody May.

From this time forward, day and night, marching, fighting, digging earthworks, there was no rest for us. From losses in battle, and from sickness, our regiment again dwindled down to a company in numbers.

On May 8th we supported the 5th Massachusetts battery, with some pretty smart fighting. On the 9th we again went to the front, and threw up works, behind which we kept pretty close most of the day. Sharpshooters were plenty in the rebel lines, not far from us. One of my company, George Erskine, who was near me in the works, sat on a cracker box, and turned his head to speak to me, thereby exposing himself a little, and as I was looking at him, I saw a bullet strike the side of his head, go through it, and strike the ground. He gave one sigh, and fell dead at my feet. It was the work of a rebel sharpshooter.

A little later in the day, the orderly sergeant asked—

“Who will go out on the skirmish line?”

The skirmish line was about a third of a mile in[61] front of us, and to reach it, one had to run the gauntlet, for the enemy had a fair view of the whole field, and they improved it, you may be sure.

Several comrades volunteered, and went under a sharp fire. I felt a little ashamed of myself for not going too, so I said to my chum,

“If he calls for more, I am going!”

“I go if you do,” said dear old Dwight, and soon the word came again,

“Who will volunteer?”

“I will go for one!” Said I, and Dwight said the same.

Over the works we went, the minie balls singing and zipping at us as we made our best time over that open field. We reached the line all right, and settled down to business.

After a time I found my ammunition was getting low, and by the time it was all gone, it was growing dark, so that we could move round with less danger, for we could not show ourselves without drawing the fire of the sharpshooters, so at dark I went round among the dead, and took all the ammunition I could find, and began again where I left off. We remained within two hundred yards of the enemy’s works all night. During[62] the night, our officers sent us plenty of ammunition, and informed us that we were to charge at noon next day, and that we were to fall into line as they advanced, but for some reason, the expected charge was delayed.

For two or three days we remained on the skirmish line, digging rifle pits to protect ourselves from the fire of the enemy. These were holes in the ground deep enough for one or more men to stand in, and if we showed our heads we were pretty sure to draw their attention, so we[64] kept out of sight as much as possible. But our greatest peril was from our own line, a quarter of a mile in the rear of us, for there were several pieces of artillery continually sending shells and solid shot over our heads into the enemy’s lines, and some of them were too near us for comfort and safety, for we were on slightly rising ground in front of them, and the gunners, to do more execution, depressed their pieces so much that every now and then a shot or shell would skim by, or over us, as we hugged the ground.

We would watch for the flash of the guns, and drop to the ground, so the shot generally went over us. In the rifle pit with me were two of my comrades, one of whom had taken off his haversack, and laid it near by. A shot from our line struck that haversack, and sent it flying in every direction.

Comrade Flint was fairly peppered with pieces of tin plate, cup, knife, fork and spoon, which wounded him severely in several places. He stood the pain as long as he could, and finally said he was going back to the lines; we advised him to wait until dark, but the pain was so great that he could not, and he started on the run across the open field, back to our main line. Instantly[65] he was a target for the rebel sharpshooters. We watched him anxiously, and once saw him go down, but he was up and off in a moment, and reached our lines, where he went into the hospital.

He received a wound in the leg, from which he never fully recovered. The other wounds healed after a while, but left indelible scars.

Soon after, the firing ceased, and we felt better, when we were no longer in danger from our own artillery.

At last, on the morning of the 12th came the order to attack, and our gallant little brigade commanded by Colonel Prescott, dashed across the field as far as the foot of Laurel Hill. How our brave boys charged those works under that heavy shower of grape and canister, none who survived will ever forget!

But we could not take the works, and had to fall back, under a galling fire from their whole line. Oh! What a shower of death came down upon us! Before we got our colors back to our old position, the 32nd had lost five color bearers, and one hundred and three, out of one hundred and ninety men, killed or wounded. A number[66] of the boys of our company lay killed or wounded upon the field we had charged over, and the constant firing along the whole line of the enemy’s works, made it dangerous business going out to bring them in; but several of us determined to do so, in spite of the risk we incurred.

Before leaving home we had made a solemn promise to each other, that no man should be left unburied or uncared for on the field; that we would risk life and limbs that our wounded should be cared for, and our dead comrades tenderly laid in the bosom of mother earth. We usually waited until night before going out after our fallen comrades, but we could see the poor fellows lying there under the scorching sun, and felt that some of them would not hold out until night.

Taking a blanket for a stretcher, four of us started out on the run, drawing upon us a deadly fire from the enemy. One of our party fell, wounded in the leg, but the rest managed to take him along in our hasty retreat. Again and again we made the attempt, succeeding in getting most of our wounded under cover.

Night came, and we started out to bury our dead. Many a poor fellow lying upon his[67] face, did I turn over in my search for my comrades that night. Suddenly I came upon one of my company, still living, but mortally wounded. He had been shot through the spine, and could not be moved, so I made him as comfortable as possible by putting a blanket under his head, and giving him some water. His sufferings were terrible, but soon over; he knew his time had come, and gave me messages for his folks and friends at home.

I promised him that I would write and let them know how, and when he died, and that I would see that he was buried. I remained with him until death released him from his agony, then closed his eyes, and covered him with his blanket.

Sadly I left him, and moved on to where I could hear a well known voice calling for help. It was another of my company badly wounded, but able to be moved, so I hastily rolled him into a blanket, and we soon had him within our line.

Busy all night, when daylight came, we had buried our dead, and gathered in our wounded, thus fulfilling the compact that was never broken when it was possible for us to keep it.[68] What a comfort it was to us, that solemn promise, for, far worse than death, was the thought of lying exposed and unburied on the battlefield. That night was a sad one, never to be forgotten by me, when we rolled our comrades up in their blankets, and laid them in graves that will forever remain unknown.

From the 12th to the 23rd, our regiment was constantly under fire from the enemy in front of us, at Spotsylvania Courthouse, and vicinity, continually changing our location, throwing up earthworks each night after a weary day’s march, before we could roll ourselves in our blankets, and take our short night’s rest.

On the morning of the 23rd, we took up our line of march towards the North Anna river,[70] crossing it at Jericho Ford, our brigade advancing at once in line of battle into a piece of woods, where we had a skirmish with the enemy, who fell back, and we proceeded to fell trees, and build a line of works.

Before we had finished them, the enemy in force, under General Hill, attacked us, and endeavored to drive us out of our works and into the river. The assault fell mainly upon our division. Our regiment was on the left of the line of battle, and we did our best to give them a warm reception. For the first time since the campaign began, we fought in our works. It was a short, sharp fight, and the enemy was repulsed.

We remained in our works until morning, when we moved on towards Hanover Junction, but on May 26th we received orders to retire, which we did during the night, and once more crossed the North Anna river at Quarles Ford, and marched almost constantly for twenty-four hours towards the Pamunky river.

We next met the enemy near Mechanicsville, on the morning of the 30th of May. Little did we think then, that in the future years, that day would be set apart for honoring the memory[71] of the fallen sons of the nation, our brigade advanced in line of battle through Tolopotomy Swamp, driving the confederate skirmishers until we came to open fields near Shady Grove Church, where we found the enemy in force behind earthworks.

We could not take them, so kept back as much as we could, out of range, yet our loss during the day was twenty-two, killed or wounded. I shall never forget our march through Tolopotomy woods, keeping in line, over briars and fallen trees and stumps. Our shoes were worn out with twenty five days of constant marching and fighting, and we were about as bad off ourselves. But we got there all the same, and staid there until midnight, when we were relieved by a part of the Ninth Corps, and went into camp, where we remained on the reserve for two or three days.

We took this time to do a little much needed washing, for we had no change of clothing, being in very light marching order. During our long marches, often, when we came to a stream, have I taken off my shirt, given it a hasty wash, wrung it out, put it on again, and gone on my way rejoicing.

[72]Perhaps the simple record kept in my diary during that “Bloody May,” as it has been so often called, will give some idea of the life we led when we were constantly confronting the enemy, with, as we might well say, a musket in one hand, and a shovel in the other; we could not stop to rest without first shoveling up earthworks to protect us from the fire of the ever active enemy.

May 1, 1864. Was relieved from picket last night, broke camp, went within one mile of Rappahannock Station. To-day crossed the Rappahannock river, and marched to Brandy Station. Corporal Tuttle left for home.

May 2. In camp near Brandy Station; sent[74] letters home. Several of the boys left us, having exchanged into the navy.

May 3. Broke camp at one o’clock P. M. Camped near Culpepper.

May 4. Broke camp last night at eleven o’clock; marched through Stephensburg, crossed the Rapidan at Germania Ford at eight A. M.; camped at one P. M., after marching fourteen hours.

May 5. In the Wilderness. Left camp, advanced half a mile, and threw up breastworks; skirmishing began, and we advanced into the fight, which was very hot work. Fell back to our works at night.

May 6. Left our line at three A. M. and went to the front; heavy skirmishing from daylight till dark. There has been some hard fighting on our left. At dark we went to the rear, then back to the front, where we stayed until midnight, then returned to our works.

May 7. Was awakened about sunrise by heavy firing all along the line. Our brigade made a charge over the works; some fighting all day.

May 8. Sunday. We moved to the right at ten P. M. last night. Came up with the enemy[75] at eight this morning; heavy fighting. We are driving the enemy. Our regiment supported the Fifth Mass. battery. Our brigade charged the rebs works, with a loss of three hundred men. Fighting near Spotsylvania Courthouse.

May 9. Started at ten o’clock last night, and went to the front. This morning threw up some works, and laid in them all day. No fighting in front of us, only skirmishing until sunset, then we had some hard fighting. Volunteered, and went out skirmishing. Erskine, of my company killed today. We were attacked twice, but the enemy was repulsed.

May 10. Our regiment supported the First New York battery today. Fighting began at half past eleven, and lasted until night. John Tidd and E. B. Hewes of my company wounded. Received a week’s mail; no letters for me.

May 11. Still supporting the First New York battery. Sent a letter home written on paper picked up on the battlefield.

May 12. Went out skirmishing at three o’clock this morning. Flint of my company, badly wounded. Later charged the enemy’s works. Wellington and Dowd of my company killed.

May 13. Was relieved from skirmish line,[76] and went to the regiment, then we started for somewhere; stopped in the woods. Lost my knapsack and everything I had.

May 14. Up in front; staid here all day, but not much fighting. Within a mile of Spotsylvania.

May 15. In front; no fighting. Formed in line of battle in advance of our works, expecting to charge the enemy’s works, but did not, for some reason to me unknown.

May 16. Laid in line of battle all day and night; no fighting. On guard.

May 17. Laid in line of battle until dark, and then advanced, and worked all night throwing up works.

May 18. Shelling began early this morning. Laid behind works all day and night. Received seven letters from home, the first I have had since we broke camp at Liberty, and they are very welcome.

May 19. Laid behind our works until about sunset, then fighting began on our right. Packed up and moved to the right. Commenced a letter to father.

May 20. Laid in line of battle behind our works. Sent letter to father.

[77]May 21. Laid behind our works until one P. M. Packed up and moved to the left; camped at eight o’clock P. M. Received letters from home.

May 22. Broke camp at four this morning, but did not start until ten o’clock. Came up with some of the enemy about two P. M. Stopped for dinner at four o’clock, then went on picket.

May 23. We started this morning at six o’clock, and crossed the North Anna river near Hanover Junction. Skirmishing began as soon as we crossed, at three P. M.; fighting began about an hour before sunset. Smart fight.

May 24. Threw up some works and laid behind them until five P. M. Packed up and moved to the right, then front, and threw up some works.

May 25. Started this morning at half past four, and advanced about two miles, then skirmishing began. Threw up some works.

May 26. Laid behind earthworks until dark, then started, and marched until eleven P. M., when we stopped for rations. Atwood wounded today. Two years ago we left Fort Warren for the front.

[78]May 27. Marched all night until half past six this morning, then stopped for breakfast near Reed’s Church. Stopped there two hours, then marched until half past five P. M. Marched for twenty-two hours.

May 28. Started this morning at half past five. Crossed the Pamunky river, and went about a mile; stopped for breakfast, and then threw up some works. Received letters from home.

May 29. Advanced two miles, rested two or three hours, then advanced another mile, when skirmishing began. Threw up some works, and stopped all night.

May 30. Packed up and started at seven this morning; skirmishing began as soon as we started. Advanced two miles, fighting all the way. Our regiment charged the enemy, with a loss of thirty men.

May 31. Regiment relieved, and sent to the rear for a brief rest. Received letters from the dear ones at home.

On the 3rd of June, before daylight, we were called up to do our part in the battle of Cold Harbor. The troops that had relieved us at the front the day before had been driven from their works, and our division was called upon to re-take them.

It was the same along the whole line. We were to charge across an open field, under a terrible[80] fire from the enemy, strongly entrenched behind earthworks. Between our line of works and that of the enemy, the ground was covered with pine trees, felled and fastened across each other, and in addition, they had posted a battery in a position that could sweep the entire unsheltered field. We heard afterwards that Lee had been two weeks getting ready for us.

It was about half past four on that bright June morning, that we started on that memorable charge. Never shall I forget the storm of bullets, grape and canister that was rained upon us. My comrades fell on my right and left till I thought there would be none left to tell the tale. Half way across, my shoe became untied, and I knew that I would lose it unless I tied it up again, so down on one knee I went, and tied my shoe.

My comrades saw me drop, and I heard a shout, “Mosby’s hit!” I was up in an instant, and on with the rest. On we went until we reached the works, from which we drove the enemy, but they only fell back to their own line of works, about two hundred yards away. We remained in the recaptured works, and kept up a constant exchange of fire all day long; on neither[81] side could a man show his head without being shot at, but we hindered them as much as we could from using their battery upon us.

I remember one poor fellow of my company, who had somehow gone to a part of our line where the enemy had a raking fire right among us. I noticed him lying there as though asleep, but I well knew that no one living could sleep in that place, and concluded that he must be dead. I offered to help his brother bring him in, but he demurred, fearing that he might share the same fate. We did not know what moment we might have to leave, and did not want to leave a dead comrade unburied.

At last four of us started after the body, and succeeded, under a terrific shower of bullets that drove us back more than once, in getting him onto a blanket, and each one holding a corner, we made quick time into the rifle pits. We rolled the poor fellow in the blanket, and buried him in one of the rifle pits; many a poor fellow was buried in that way.

There was a peach orchard between the lines, and when the battle ended at dark, there was not much left of it but the trunks of the trees. All day I kept pegging away. When[82] my gun got too foul from constant firing, I poured in a little water, washed it out, snapped a cap or two, and I was ready for action again. I was not sorry however, when nightfall put an end to the conflict, and I could drop down and rest.

Another charge was ordered before night, all along the line, but the order was countermanded, thus saving many precious lives. The loss of our army that day was over thirteen thousand men, our regimental loss being ten killed, and twenty-one wounded.

The next morning at daybreak I heard the orderly call my name, and reported to him immediately, and received the order with others,

“On the skirmish line!”

While I stood waiting a few moments for the skirmishers to get together, I noticed a Johnny Reb walking over to our line; I thought he wanted to come in, so I shouted to him to come on in; he stopped and looked at me a moment as though surprised, then turned on his heel, and walked back from whence he came, taking no notice of my invitation to come in, and threat to shoot him if he didn’t. I would not have shot the brave fellow anyway, and I watched him walk deliberately back until he reached the works,[83] when he leaped over them and ran for the woods like a deer. We concluded that he was a straggler who had been asleep somewhere, and did not know of the changed conditions, and thought his side still held the advanced line; at any rate, he found out the difference before it was too late.

Only a few moments elapsed before we were ready for the start, and away we went, expecting every minute the rebels would rise above their works, and put an end to us all. But all was quiet in front, so we kept on until we stood upon their works, and found that during the night the enemy had left for parts unknown. Upon a cracker box cover they had left the loving message,

“Come on, you damned Yanks to Richmond, but you will find it a rough road to travel, with a Hill, and two Longstreets to go over before you get there!”

You can imagine how surprised we were to find the works abandoned that our leaders had thought it impossible to capture by assault, and how thankful we were that we had not made the charge that the enemy had evidently expected, and so had prudently withdrawn, under cover of[84] darkness. They had succeeded in removing their battery that had so raked us all day, but the heap of dead horses, a dozen or more, that lay near the position they had occupied, showed that they had made several attempts before they accomplished their purpose.

On the 12th of June, General Grant changed his plan of operations, and started us off for the James river. Our corps crossed the Chickahominy river at Long Bridge, marched southward to the James river, and on the 16th of June, the Army of the Potomac was on the right bank of the James, preparing for a fresh start in another direction. As we went up in front of Petersburg on the 18th of June, we were double quicked across an open field, and made a dash on the Norfolk railroad, where we made a stand.

It was in this charge that our beloved colonel, George L. Prescott, fell mortally wounded, while leading his men. He died the next day, and the whole brigade mourned his loss; he was a brave soldier, and a good man; always kind to his men, he treated them like brothers.

Many a time have I known him to let a sick man have his blanket, and then bunk in with a private who was lucky enough to have such an article. More than once has he slept with me, rolled up in the same blanket, and I always felt that in him I had a true friend. By his kind and generous words and deeds he had endeared himself to the whole brigade, and today many an old veteran reveres his memory, even as I do.

His body was brought home, and buried with his kindred in Sleepy Hollow cemetery, at Concord, Mass. I have visited his grave since the war, and as I stood in the pleasant spot where he sleeps so peacefully, I could but recall the[86] memories of that terrible scene, when he laid his life on the altar of his country.

We had hot work all that day; again we charged the enemy, and drove them into their last line of works. This enabled us to establish our line on the crest of the hill. Near this place the mine was made that was exploded on the 30th of July, a little over a month later.

It was in this charge that a minie ball grazed my check, which soon swelled so that my comrades hardly recognized me. For a week or more, my jaw was rather stiff and sore, so that I could not eat hard bread; this made it rather inconvenient, as I was blessed with a good appetite and could not get much else but the old reliable “Hard tack” to eat, but I was not disabled, and did my duty as usual.

It was about noon, during a lull in the fight, that we saw a large turkey strut proudly into the centre of a deep ravine, that lay between us and the enemy’s lines. Instantly every musket in our company was aimed at that poor turkey gobbler. When the smoke cleared away, we saw him still undisturbed in his foraging; we stood astonished until one of us happened to remember that our guns were sighted for 200 yards[87] distance. He hastily lowered the sight, and spang went the deadly messenger into the heart of that devoted bird. When the fight was over, we picked up the fowl, and cooked him for our supper.

That night we spent in throwing up earthworks with our bayonets and tin plates, and by morning we had some works from which the enemy could not drive us, though they made several attempts. Our works were never advanced beyond this line until Petersburg was taken.

June 1, 1864. Sunset. Another battle has begun, and brave men are now falling for their country and their homes. Ah, many a heart will mourn when they hear of this hour’s history, but may the thought cheer them, that their dear ones fell like heroes, as they are, in the holiest cause for which man ever fought.

[89]June 2. Five P. M. Again has the battle begun, and again we hear the hum of lead and iron, like hail in a storm. Oh, how terrible is the conflict of arms among men of one nation!

June 3. The battle began early this morning, and now many of my dear comrades are cold in death. Many others are suffering with pain from wounds received while facing traitors to their country.

At six o’clock this morning we charged across a field about a quarter of a mile; fighting began, and we had it hot and heavy until dark. Our loss was very heavy, and of my company, Warren P. Locke, and Makepeace C. Young are killed, and Hazen, Kennison, Robinson, Melvin, Parsons, Beals, Uffindale, and Fuller are wounded. Oh, may their names be ever honored by those who love their country!

June 4. Went out skirmishing; relieved at noon, and joined my company. Started for some place, and went about one mile, then back we went to the front, and staid all night.

June 5. Laid behind our works until four P. M., then with two other regiments, we went out on a reconnoissance; skirmishing began soon after starting, and we fell back to our works, got our[90] rations, and fooled around all night.

June 13. Started at eight o’clock last night, and marched until half past four this morning, when we halted near the Chickahominy river; laid down an hour, then up and going again. Stopped for breakfast at seven o’clock. Crossed the Chickahominy, and went about a mile, then halted until dark; then packed up and started for Charles City courthouse. Stopped at midnight.

June 14. Once more back on the James river. I little thought one year ago that I should ever return here. But where are my companions that were with me then? Some are lying beneath Virginia soil, others are wounded in the hospitals, and others are at home with their friends; but I am still in my country’s service, fighting for the Nation that was given to us by our forefathers.

June 18. This day will ever be fresh in my memory, for through the mercy of God, my life was spared, when death certainly stared me in the face. While men fell all around me, I was left unharmed. It was a desperate attempt to carry the enemy’s works; we charged three times and were repulsed each time, with terrible loss. Our Colonel fell, fatally wounded, while leading[91] his men in the charge. Major Edmunds was wounded; William R. Wait was killed, and Wheeler and many others of my company were wounded.

June 19. Col. Prescott died of his wounds today at 11 A. M. He was a good and brave man and we deeply feel his loss.

July 30. Before Petersburg. Battle opened all along the line before sunrise this morning. About as heavy artillery firing as I ever heard. There is hard fighting on the left and centre of our line.

August 18. On guard last night; packed up at three this morning, and moved to the left across the Weldon railroad, and tore up the rails. Heavy fighting all day; was on the skirmish line; Melvin of my company wounded; was relieved from the skirmish line at 10 o’clock tonight.

August 21. Sunday; on the Weldon railroad; just got my breakfast down when the outposts of our line were driven in; we opened fire, but were driven back to our works, then we advanced, skirmishing all the way back to our old picket line.

After our line of entrenchments was established, our brigade was ordered to the rear, and we encamped along the Jerusalem plank road, where we were held in reserve for special duty. Here we worked day and night building[93] a large earthen fort, which we named in honor of our lamented Col. Prescott. Here Major Edmunds was appointed colonel, and took command of the regiment.

We remained in reserve about three weeks, during which time we were called upon to re-enforce the Second and Sixth Corps, on two occasions. On July 12th we were ordered into the trenches, where we lived in bomb proofs for five weeks, one of the hardest experiences of my army life. These bomb proofs were a sort of artificial cavern, which we had to construct under cover of darkness, for the enemy was continually sending over to our lines solid shot and hissing shells, and only in our bomb proofs, (and not always there,) were we out of danger from them.

To build a bomb proof we dug a hole in the ground about four feet deep if the ground was dry, but where our regiment was located it was so springy that two feet brought us to water so most of ours were partly above ground; after the hole is dug, the top was roofed over with logs, and dirt thrown on top of them. A small space was left open towards our rear for a door to go in and out of, which was sheltered by a log canopy. Here we had to stay, and hot, uncomfortable,[94] and unhealthy places they proved to be, and it is no wonder that many of our men were taken from them to the hospital, sick with malarial fever, from which some of them never recovered.

I remember one hot night, my chum and I pitched a tent two or three steps in the rear of our bomb proof under a pine tree, and there we went to sleep. Before morning, the active enemy in front began shelling our line, and we were awakened by the falling of the branches upon our tent, having been cut off by a passing shot. Soon another shot came and struck the tree, and my bedfellow made one leap out of the tent into the bomb proof. The next shot struck the tree still lower, and I too forsook my bed for the safer, though uncomfortable hole in the ground.

Sometimes, when the guns in front of us were silent, we would sit on the bomb proofs in the evening, and watch the shells of the enemy, as they came over on to some other part of our entrenchments. It was a beautiful sight, far beyond any fireworks I have ever witnessed, if we could only forget their deadly errand.

On the 30th of July occurred the explosion of the Burnside mine, that we had made by[95] digging a passage to and under one of the rebel forts, and laying powder enough to destroy it. The plan had been carefully laid, and an attack contemplated simultaneous with the explosion, which would carry their line.

The blowing up of that mine was a horrible affair, and caused much slaughter, but for some reason, the attack was not a success. The artillery opened all along our line, on that eventful morning, as a signal for the beginning of the fight.