Walker & Boutall, ph. sc.

The Earl Marischal

1717.

THE

COMPANIONS OF PICKLE

PICKLE THE SPY; or, The Incognito of Prince Charles. With 6 Portraits. 8vo. 18s.

ST. ANDREWS. With 8 Plates and 24 Illustrations in the Text by T. Hodge. 8vo. 15s. net.

THE MAKING OF RELIGION. 8vo. 12s.

MODERN MYTHOLOGY: a Reply to Professor Max Müller. 8vo. 9s.

HOMER AND THE EPIC. Crown 8vo. 9s. net.

CUSTOM AND MYTH: Studies of Early Usage and Belief. With 15 Illustrations. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d.

LETTERS TO DEAD AUTHORS. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net.

BOOKS AND BOOKMEN. With 2 Coloured Plates and 17 Illustrations. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net.

OLD FRIENDS. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net.

LETTERS ON LITERATURE. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net.

GRASS OF PARNASSUS. Fcp. 8vo. 2s. 6d. net.

ESSAYS IN LITTLE. With Portrait of the Author. Crown 8vo. 2s. 6d.

COCK LANE AND COMMON-SENSE. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d.

THE BOOK OF DREAMS AND GHOSTS. Crown 8vo. 6s.

ANGLING SKETCHES. With 20 Illustrations. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d.

A MONK OF FIFE: a Story of the Days of Joan of Arc. With 13 Illustrations by Selwyn Image. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d.

LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO., 39 Paternoster Row, London

New York and Bombay.

Walker & Boutall, ph. sc.

The Earl Marischal

1717.

THE

COMPANIONS OF PICKLE

BEING A SEQUEL TO ‘PICKLE THE SPY’

BY

ANDREW LANG

WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK AND BOMBAY

1898

All rights reserved

The appearance of ‘Pickle the Spy’ was welcomed by a good deal of clamour on the part of some Highland critics. It was said that I had brought a disgraceful charge, without proof, against a Chief of unstained honour. Scarcely any arguments were adduced in favour of Glengarry. What could be said in suspense of judgment was said in the Scottish Review, by Mr. A. H. Millar. That gentleman, however, was brought round to my view, as I understand, when he compared the handwriting of Pickle with that of Glengarry. Mr. Millar’s letter on the subject will be found in this book (pp. 247, 248).

The doubts and opposition which my theory encountered made it desirable to examine fresh documents in the Record Office, the British Museum, and the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, while General Alastair Macdonald (whose family recently owned Lochgarry) has kindly permitted me to read Glengarry’s MS. Letter Book, in his possession. The results will be found in the following pages.

Being engaged on the subject, I made a series of[vi] studies of persons connected with Prince Charles, and with the Jacobite movement. Of these the Earl Marischal was the most important, and, by reason of his long life and charming character—a compound of ‘Aberdeen and Valencia’—the most interesting. As a foil to the good Earl, who finally abandoned the Jacobite party, I chose Murray of Broughton, who, though he turned informer, remained true in sentiment, I believe, to his old love. His character may, perhaps, be read otherwise, but such is the impression left on me by his ‘Memorials,’ documents edited recently for the Scottish History Society by Mr. Fitzroy Bell.

In Barisdale, whose treachery was perfectly well known at the time, and was punished by both parties, we have a picture of the Highlander at his worst. Culloden made such a career as that of Barisdale for ever impossible.

In the chapters on ‘Cluny’s Treasure’ and ‘The Troubles of the Camerons’ I have, I hope, redeemed the characters of Cluny and Dr. Archibald Cameron from the charges of flagrant dishonesty brought against them by young Glengarry. Both gentlemen were reduced to destitution, which by itself is incompatible with the allegations of their common enemy.

‘The Uprooting of Fassifern’ illustrates the unscrupulous nature of judicial proceedings in Scotland after Culloden. A part of Fassifern’s conduct is not easily explained in a favourable sense, but he was persecuted in a strangely unjust and intolerable[vii] manner. Incidentally it appears that public indignation against this sort of procedure, rather than distrust of ‘what the soldier said’ in his ghostly apparitions, procured the acquittal of the murderers of Sergeant Davies.

‘The Last Days of Glengarry’ is based on a study of his MS. Letter Book, while ‘The Case against Glengarry’ sums up the old and re-states the new evidence that identifies him with Pickle the Spy.

The last chapter is an attempt to estimate the social situation created in the Highlands by the collapse of the Clan system.

I have inserted, in ‘A Gentleman of Knoydart,’ an account of a foil to Barisdale, derived from the Memoirs of a young member of his clan, John Macdonell, of the Scotus family. The editor of Macmillan’s Magazine has kindly permitted me to reprint this article from his serial for June 1898.

A note on ‘Mlle. Luci’ corrects an error about Montesquieu into which I had fallen when writing ‘Pickle the Spy,’ and throws fresh light on Mlle. Ferrand.

It is, or should be, superfluous to disclaim an enmity to the Celtic race, and rebut the charge of ‘not leaving unraked a dunghill in search for a cudgel wherewith to maltreat the Highlanders, particularly those who rose in the Forty-five.’ This elegant extract is from a Gaelic address by a minister to the Gaelic Society of Inverness.[1] I have not[viii] raked dunghills in search of cudgels, nor are my sympathies hostile to the brave men, Highland or Lowland, who died on the field or scaffold in 1745-53. The perfidy of which so many proofs come to light was in no sense peculiarly Celtic. The history of Scotland, till after the Reformation, is full of examples in which Lowlanders unscrupulously used the worst weapons of the weak. Historical conditions, not race, gave birth to the Douglases and Brunstons whom Barisdale, Glengarry, and others imitated on a smaller scale. These men were the exceptions, the rare exceptions, in a race illustrious for loyalty. I have tried to show the historical and social sources of their demoralisation, so extraordinary when found among the countrymen of Keppoch, Clanranald, Glenaladale, Scotus, and Lochiel.

I must apologise for occasional repetitions which I have been unable to avoid in a set of separate studies of characters engaged in the same set of circumstances.

My most respectful thanks are due to Her Majesty for her gracious permission to study the collection of Cumberland Papers in her library at Windsor Castle. Only a small portion of these valuable documents has been examined for the present purpose. Mr. Richard Holmes, Her Majesty’s Librarian, lent his kind advice, and Miss Violet Simpson aided me in examining and copying these and other papers referred to in their proper places. Indeed I cannot overestimate my debt to the research and acuteness of this lady.

To General Macdonald I have to repeat my thanks for the use of his papers, and the Duke of Atholl has kindly permitted me to cite his privately printed collections, where they illustrate the matter in hand.

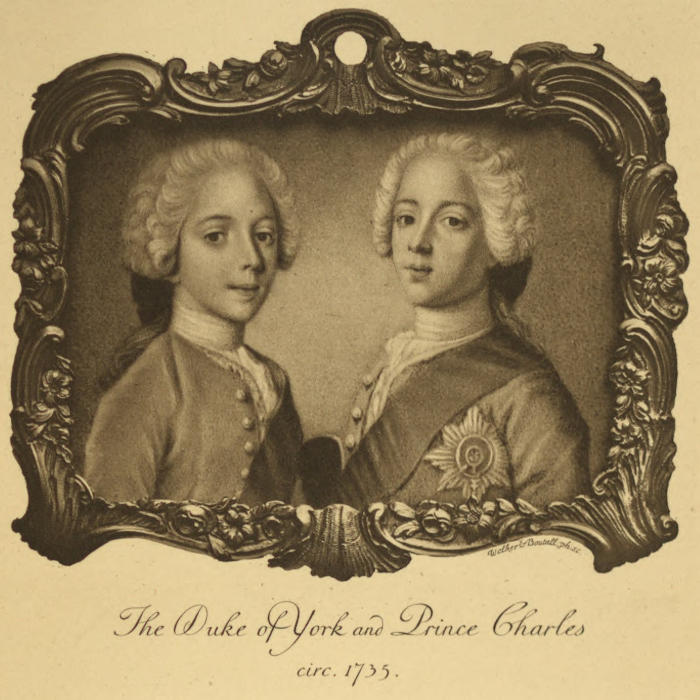

Sir Thomas Gibson Carmichael was good enough to lend me, for reproduction, his miniature of the Duke of York and Prince Charles.

The earlier portrait of the Earl Marischal is from the Scottish National Museum, the later (of 1752?) is from the National Portrait Gallery. It gives a likeness of one of the good Earl’s menagerie of young heathens. The miniature of Prince Charles (p. 140) is a copy or replica of one given by him to a Macleod of the Raasay house in September, 1746. The Royal Society of Edinburgh kindly permitted me to have copies made of several of the Earl Marischal’s letters to David Hume, in their possession. In some of these (unprinted) the Earl touches on a theme for which le bon David frankly expresses his affection in a letter to the Lord Advocate.

P. 12, note, for twenty-two in 1716, read twenty-three

P. 17, note, for 33,900 read 33,950

Transcriber’s Note: These corrections didn’t need making: presumably the printers did it, but neglected to remove this list.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | THE LAST EARL MARISCHAL | 1 |

| II. | THE EARL IN RUSSIAN SERVICE | 42 |

| III. | MURRAY OF BROUGHTON | 69 |

| IV. | MADEMOISELLE LUCI | 92 |

| V. | THE ROMANCE OF BARISDALE | 97 |

| VI. | CLUNY’S TREASURE | 129 |

| VII. | THE TROUBLES OF THE CAMERONS | 147 |

| VIII. | JUSTICE AFTER CULLODEN | 158 |

| IX. | A GENTLEMAN OF KNOYDART | 176 |

| X. | THE LAST YEARS OF GLENGARRY | 198 |

| XI. | THE CASE AGAINST GLENGARRY | 216 |

| XII. | OLD TIMES AND NEW | 254 |

| APPENDIX | ||

| I. | PICKLE’S LETTERS | 289 |

| II. | MACLEOD | 294 |

| INDEX | 297 | |

| THE EARL MARISCHAL (1717) | Frontispiece | |

| THE EARL MARISCHAL (circ. 1750) | to face | p. 60 |

| PRINCE CHARLES (circ. 1744) | ” | 140 |

| THE DUKE OF YORK AND PRINCE CHARLES (circ. 1735) | ” | 184 |

In a work where we must make the acquaintance of some very unfortunate characters, it is well to begin with a preux chevalier. If there was a conspicuously honest man in the eighteenth century, one ‘whose conscience might gild the walls of a dungeon,’ as an observer of his conduct declared, that man was the Earl Marischal, George Keith. The name of the last Earl Marischal of Scotland haunts the reader of the history of the eighteenth century. He appears in battles for the Stuart cause in 1715 and 1719, he figures dimly in the records of 1745, and of Charles Edward, after the ruin of Culloden. We find him in the correspondence of Voltaire, Rousseau, Hume, and Frederick the Great, and even in Casanova. He is obscurely felt in the diplomacy which ended in Pitt’s resignation of office. Many travellers describe his old age at Potzdam, and d’Alembert wrote his Éloge.[2] He was the last direct representative of that historical house of Keith whose laurels were first won in the decisive charge of Bruce’s handful of cavalry on the English archers at Bannockburn. Though the Earl Marischal of the confused times after the death of James V. was a pensioner of Henry VIII., like so many of the Scottish noblesse, the House was Royalist, and national as a rule. Yet, after a long life of exile as a Jacobite, the last Earl Marischal, always at heart a Republican, reconciled himself to the House of Hanover. The biography of the Earl has never been written, though few Scottish worthies have better deserved this far from uncommon honour.

Materials for a complete life of the Earl do not exist. We are obliged to follow him by aid of slight traces in historical manuscripts, biographies, memoirs, and letters, published or unpublished. Even in this unsatisfactory way, the Earl is worth pursuing: for if he left slight traces on history, and was never successful in action, he was a man, and a humourist, of singular merit and charm, a person almost universally honoured and beloved through three generations. This last of the Earls Marischal of Scotland was certainly one of the most original and one of the most typical characters of the eighteenth century. Losing home, lands, and rank for the cause of Legitimism, the Earl was the reverse of a fanatical Royalist; indeed he seems to have become a Jacobite from Republican principles. These were strengthened, no doubt, by his great experience of kings; but even when[3] he was a young man his bookplate bore the motto Manus hæc inimica tyrannis. Then probably, as certainly in later life, he loved to praise Sidney, and others who (in his opinion) died for freedom. Yet the Earl was ‘out,’ for no Liberal cause, in 1715, and in 1719: while he was plotting against King George and for King James, till 1745. He was admitted to the secret of the rather Fenian Elibank Plot in 1752, and only reconciled himself with the English Government in 1759. On his death-bed he called himself ‘an old Jacobite,’ while, for twenty years at least, his favourite companions had been the advanced thinkers, prelusive to the Revolution, Rousseau, Hume, d’Alembert, Voltaire, Helvetius.

All this appears the reverse of consistent. The Earl gave up everything, and risked his life often, for the White Rose, while his opinions, religious and political, tended in the direction of the Red Cap of Liberty and the Rights of Man. The explanation is that the Earl, when young, a patriotic Scot, and a persecuted Episcopalian, saw ‘freedom’ in the emancipation of Scotland from a foreign tyrant, the Elector of Hanover; in the Repeal of the Union, and in the relief of his religious body from the tyranny of the Kirk. Till his death he was all for liberty, and could not bear to see even a caged bird. These were the unusual motives (these, and the influence of his mother, a Jacobite by family and sentiment) which converted a born Liberal into a partisan of the King over the Water. Thus this representative[4] of traditional and romantic Scottish loyalty to the Stuarts was essentially a child of the advanced, and emancipated, and enlightened century which succeeded that into which he was born.

Original in his political conduct, the Earl was no less unusual in personal character. He was one of those who, as Plato says, are ‘naturally good,’ naturally examples of righteousness in a naughty world. Nature made him temperate, contented, kind, charitable, brave, and humorous—one who, as Montaigne advises, never ‘made a marvel of his own fortunes.’ His virtue, as far as can be learned, owed nothing to religion. He was ‘born to be so,’ as another man is born to be a poet. He had a native genius for excellence.

He was ruined without rancour, and all the buffets of unhappy fortune, all the political and social vicissitudes of nearly a century, could not cloud his content, or diminish his pleasure in life and the sun. He was true to his exiled Princes, till they, or one of them at least, ceased to be true to themselves. He was perhaps the only friend whom Rousseau could not drag into a quarrel or estrange, and the only companion whom Frederick the Great loved so well that he never made experiments on him in the art of tyrannical tormenting. Familiar, rather than respectful, with Voltaire, the Earl, who remembered Swift in his prime, was fond of gossiping with Hume and of bantering d’Alembert. Kind and charitable to all men, he was especially[5] considerate and indulgent to the young, from the little exiled Duke of York to the soured Elcho, and the still unsuspected Glengarry. One exception alone did the Earl make (unless we believe Rousseau): he could not endure, and would not be reconciled to, Prince Charles. If in this he may seem severe, no other offence is laid to his charge, though modern opinion may condemn his cool acquiescence in desperate plots which he probably never expected to be carried into action. Otherwise the Earl presents the ideal of a good and wise man of the world, saved from all excess, and all disappointment, by the gifts of humour and good-humour. When we add that ‘the violet of a legend,’ of unfortunate but life-long love, blows on the grave of the good Earl, it will be plain that, though not a hero, like his brother, Marshal Keith, he was a character of no common distinction and charm. His life, too, is almost an epitome of the Jacobite struggle from 1715 to 1757. The Earl was ever behind the scenes.

Though tenth Earl (the first of the hereditary Marischals to be ‘belted earl’ was William, in 1458), George Keith was apt to mock at hereditary noblesse. Stemmata quid faciunt? He had a story of a laird who grumbled, during a pestilence, ‘In such times a gentleman is not sure of his life.’ The date of his birth was never known. In old age he cast an agreeable mystery about this point. He was once heard to say that he was twenty-seven in 1712; if so, he died at ninety-three (1778). Others date his[6] birth in 1693, others in 1689; d’Alembert says (on the authority of one who had the fact from Ormonde) that he was premier brigadier of that general’s army in 1712. An engraving from a portrait of the Earl as a young man represents him as then twenty-three years of age. If the engraving was done in Paris, as seems probable, in 1716, he would be born in 1693. Oddly enough the pseudo-Memoirs of Madame de Créquy (who is made to speak of him as her true love) throw a similar cloud over the year of her birth. Concerning the Earl’s father, Lockhart of Carnwath writes that he had great vivacity of wit, an undaunted courage, and a soul capable of great things, ‘but no seriousness.’ His mother, of the house of Perth, was necessarily by birth a Jacobite. The song makes her say:

The Earl’s tutor was probably Meston, the Jacobite wit and poet.

The Earl succeeded his father in 1712. His own first youth had been passed in Marlborough’s wars; from 1712 to the death of Queen Anne, and the overthrow of hopes of a Restoration by the Tories, he lived about town, a brilliant colonel of Horse Guards, short in stature and slight in build, but with a beautiful face, and dark, large eyes. So we see him in the portrait of about 1716.

The following letter, the earliest known letter of the Earl, displays him as a disciplinarian. Conceivably[7] the mutinous Wingfeild was a Jacobite, but, by September 12, 1714, the chance for a rising of the Guards for King James had passed, Queen Anne was dead, and the Earl was still colonel in the army of George I.

To Lord Chief Justice Parker

Stowe MSS. 750, f. 58.

‘September 12, 1714.

‘My Lord,—As soon as I heard that your Lordship had granted a Habeas Corpus for Thomᵃˢ Wingfeild one of the private men of His Majesties Second Troop of Horse Grenadier Guards under my Command, I sent a Gentleman to wait upon your Lordship and to acquaint you with the reasons for my ordering Wingfeild to be confin’d to the Marshall of the Horse Guards according to the practice of the Army, but your Lordship was not then at your Chambers; I now take the liberty to inform you that the Prisoner has not only been guilty of uttering menacing words & insolently refusing to comply with the establisht Regulations of the Troop, (to which Regulations he has subscribd) but has also been endeavouring to raise a mutiny therein, which crimes among Soldiers being of dangerous Consequences I did intend to have him try’d by a General Court Martial, that he might have been exemplarily punisht as far as the Law allows to deter others from the like practices: but as there is no warrant for holding a Court Martial for the Horse Guards extant, & I being unwilling to trouble their[8] Excellᶜⁱᵉˢ the Lords Justices on this occasion, I had ordered my officers to hold a Regimental Court Martial upon him yesterday in order to break him at the head of the Troop, which is the only punishment they can inflict, but they did not proceed then on accoᵗ of the Habeas Corpus; this I thought fit to acquaint your Lordship with and to assure you that I am &c.

‘Marischall.’

From Lockier, Spence got the familiar anecdote of the Earl’s conduct at Queen’s Anne’s death, before the projects for a Restoration of the Chevalier were completed. Ormonde, Atterbury, and the Earl met, when Atterbury bade Marischal go out (with the Horse Guards) and proclaim King James. Ormonde wished to consult the Council. ‘Damn it,’ says Atterbury in a great heat (for he did not value swearing), ‘you very well know that things have not been concerted enough for that yet, and that we have not a moment to lose.’ That moment they lost, and a vague anecdote represents the Earl as weeping, after the battle of Sheriffmuir, over the many dead men who might have been alive had he taken Atterbury’s advice. D’Alembert, who does not mention Atterbury, attributes the idea of an instant stroke for the King to the Earl himself.[2]

When the rising of 1715 was in preparation,[9] the Earl, according to d’Alembert, wrote to James, telling him that ‘a sovereign deprived of his own must share the dangers of those who risked their lives for his sake,’ and so made him ‘leave his retreat’ at Bar-le-Duc. But James’s natural brother, the Duke of Berwick, on July 16, 1715, had already given the same advice. ‘Your honour is at stake, your friends will give over the game if they think you backward.’ James replied that he hoped to be at Dieppe by the 30th of the month. Within five days Berwick was crying off from the task of accompanying his brother, who replied with a repressed emotion, ‘You know what you owe to me, what you owe to your own reputation and honour, what you have promised to the Scotch and to me.... I shall not, therefore, bid you adieu, for I expect that we shall soon meet.’

It was now not the King who turned laggard, but Berwick who advised delay. ‘I find Rancourt’ (the King), he says, ‘very much set on his journey.’ In brief, it was Berwick and Bolingbroke who kept James back, though with great difficulty. He needed no urging (as d’Alembert suggests) by our Earl. ‘I fear I shall scarce be able to hinder him from passing the sea,’ says Berwick (August 6).

Then Louis XIV. died, all was confusion, and the Regent Orléans detained Berwick in France, exactly at the time when Mar went to raise the Highlands. What with Bolingbroke, Berwick, the death of Louis XIV., and the intrigues of Orléans in[10] the Hanoverian interest, James, travelling disguised through an Odyssey of perils, did not leave France for Scotland till mid-December. A month before (November 13) Mar had been practically defeated at Sheriffmuir, and Forster, Mackintosh, Derwentwater and Kenmure had surrendered at Preston. The King thus came far too late, but certainly by no lack of readiness on his part.

D’Alembert makes the Earl utter a fine constitutional speech on the duties of a king when he proclaimed James at Edinburgh. Unluckily, on this occasion James was never proclaimed at Edinburgh by anybody. The Éloge of d’Alembert is eloquent, but it is not history. It has been the chief source for the Earl’s biography.

The Earl had doubtless been won over by Mar to resign his English commission, and desert King George for King James. The story is told that, as he rode North from London in 1715 to join Mar in the Highlands, he met his young brother James riding South to take service with King George. He easily induced his brother to share his own fortunes, and Prussia ultimately gained the great soldier thus lost to England. The Covenanting historian, Wodrow, avers that ‘Marischal was bankrupt,’ and therefore eager for res novæ. But he would have been a Jacobite in any case. As to the Earl’s conduct when Mar’s ill-organised and ill-supplied rising drew fatally to a head at Sheriffmuir, his brother, the Field-Marshal of Prussia, in his fragmentary Memoir,[11] tells all that we know. The Earl, with ‘his own squadron of horse’ and some Macdonalds, was sent to occupy a rising ground, the enemy being, as was thought, in Dunblane. From the height, however, the whole hostile army was seen advancing, and the Earl sent to bid Mar bring up his forces. There was much confusion, and the Earl’s squadron of horse was left in the centre of the line. Mar’s right with the Earl routed Argyll’s left, while Argyll’s left routed Mar’s right. ‘In the affair neither side gained much honour,’ says Keith, ‘but it was the entire ruin of our party.’ Half of Mar’s force, having thrown down their plaids,[3] were now unclothed: many had deserted; the evil news of the Preston surrender came, the leaders were at odds among themselves, 6,000 Dutch troops were advancing from England. Seaforth and Huntly took their followers back to the North, and when King James arrived at Perth, late in December, he found a wintry welcome, soldiers few and dispirited, and dissensions among the officers. The army wasted away while Cadogan, Argyll, and the Dutch troops, greatly outnumbering the Jacobites, advanced on Perth through the snow.

James’s army now beat a retreat, with no point to make for, as Inverness was in the hands of the enemy. Mar, therefore, advised James, who had not ammunition enough for one day’s fight (thanks to Bolingbroke,[12] said the Jacobites), to take ship at Montrose. If he stayed, the enemy would make their utmost efforts to come up with and capture him. If he departed, the retreating Highlanders would be less hotly pursued. James consulted Marischal, who wished to offer no opinion, alleging ‘his age and want of experience,’ says Keith.[4] Finally, he privately admitted to Mar that ‘he did not think it for the King’s honour, nor for that of the nation, to give up the game without putting it to a tryall.’ Powder enough for one day’s fight could be got at Aberdeen; he hoped to gain recruits as they went North, and, at worst, James, if beaten, could escape from the West coast. ‘Mar seemed to be convinced of the truth of this’ (very like Bobbing John); ‘however, a ship was already provided,’ and James, with Mar, Melfort, and others, eloped; the King characteristically leaving all his money to recompense the peasants who had suffered by the war. James was no coward, he had charged the English lines repeatedly, at the head of the Royal Household, in the battle of Malplaquet, where he was wounded. In his journey from Lorraine to the coast he had run the gauntlet of Stair’s cut-throats. But a Scottish winter, a starveling force, no powder, and Mar’s advice, had taken the heart out of the adventurer.

According to Mar, the Earl had orders to sail with the King, ‘who waited on the ship above an hour and a half, but, by what accident we yet know not, they did not come, and there was no waiting longer.’[5] ‘The King and we are in no small pain to know what is become of our friends wee left behind.’ D’Alembert says that the Earl refused to sail. ‘Your Majesty is to protect yourself for your friends. I shall share the sorrows of those who remain true to you in Scotland, I shall gather them, and shall not leave without them.’ If Mar tells truth, the Earl can have made no such speech. A modest man, he remained at his duty without rhetoric.

The dispirited and deserted Highland army moved North, and the Earl was sent to ask Huntly whether he would join them—in which case they would fight at Inverness—or not. ‘He easily perceived by Huntly’s answer that nothing was to be expected from him.’ They, therefore, marched to Ruthven, whence they scattered, Keith and the Earl fared westwards with Clanranald’s men, and made for the Islands. Hence they sailed in a French ship on May 1, and reached St. Pol de Léon on May 12. There were a hundred officers of them together, and all this destroys d’Alembert’s romance, modelled on the adventures of Prince Charles, about the Earl’s dangers and the noble behaviour of the crofters among whom he was wandering. An English force was, indeed, at one time within thirty miles of[14] the fugitives, but there was nobody to whom Clanranald’s men could have been betrayed, not that any one was likely to betray them, and the Earl Marischal and James Keith with them. In truth, d’Alembert confused this occasion with another, after Glenshiel fight, in 1719.

Many of the fugitives went to James at Avignon, but Keith stayed in Paris, where Mary of Modena received him well. ‘Had I conquered a kingdom for her she could not have said more.’ She gave him 1,000 livres, while James granted what he could, 200 crowns yearly. Keith does not say that the Earl was in Paris, where his portrait was probably painted at this date. There, however (as is known from an unpublished MS.), he certainly was, and he might even, by Stair’s mediation, have obtained his pardon. But he supposed that the cause would presently triumph, and declined to make any advances to George I. He was now in correspondence with General Dillon, James’s military representative in Paris. In August, 1717, Dillon writes to him about one ‘Prescot,’ who is suspected of intending to murder James in Italy; he refers to Lord Peterborough, who was arrested on this impossible charge at Bologna in September 1717.[6] In 1719 the Earl and his brother went to Spain. There was then war between Spain and England, Ormonde was with Alberoni, and was to be employed. Keith would have gone thither[15] earlier, but ‘I was then too much in love to think of quitting Paris.’

Here, in Paris, 1717-18, if ever, would have to be fixed the Earl’s legendary romance with Mademoiselle de Froullay (Madame de Créquy). The story, a very pretty one, is given in this lady’s Mémoires, an ingenious but fraudulent compilation.

An author best known for his plagiarisms seized on Madame de Créquy as a likely old person to have left memoirs behind her. By aid of gossip and books he patched up the amusing but mythical records which he attributed to the lady. Why he selected the Earl as the lover of her girlhood we can only guess; but dates and facts make the pretty tale incredible, though it has found its way into Chambers’s account of the Earl’s career. Thus, for example, it is averred by Sainte-Beuve, on the authority of her man of business, M. Percheron, that Madame de Créquy was born in 1714. The love story of 1717, told in her Memoirs, beginning in the Earl’s attempt to teach her Spanish and English, and interrupted by the fact that he was a ‘Calvinist,’ is therefore improbable. The lady was but three years old when her affections, according to her apocryphal Memoirs, were blighted. The lovers met again, when the Earl was Prussian Ambassador at Versailles in 1753. ‘We had not had the time to discover each other’s faults, we had not suffered each by the other’s imperfections, both remained under that illusion which experience destroyed not: we were happy in the sweet thought of[16] ineffable excellence, and when we met in the wane of life, and either saw the other’s white hair, we felt an emotion so pure, so tender, and so solemn, that no other sentiment, no other impression known to mortals, can be compared to it.’ All this is charming, but it cannot conceivably be true! The Earl composed his one madrigal under the influence of this elderly emotion (say the pseudo-Memoirs), a tear stole down his withered cheek, and he assured Madame de Créquy that they would meet in Heaven. ‘I loved you too much not to embrace your religion.’ So runs the romance of the pseudo-Madame Créquy.

In fact, the Earl remained a member of the persecuted Episcopal Church in Scotland. In Rome a priest tried to convert him, beginning with the Trinity. ‘Your Lordship believes in the Trinity?’ ‘I do,’ said the Earl; ‘but that just fills up my measure. A drop more and I spill all.’

Madame de Créquy’s Mémoires are obviously a daring forgery, but the ‘violet of a legend’ has a fragrance of its own. The Earl was in 1716, as his portrait shows, a singularly handsome young man, with large hazel eyes and an eager face, with a complexion like a girl’s beneath his brown curls. Madame de Créquy is made to say, by way of giving local colour, that he greatly resembled a portrait of le beau Caylus, a favourite of Henri III. The portrait was in her family.

In 1719, to return to facts, the two Keiths were received in Spain by the Duc de Liria, son of the[17] Duke of Berwick, who had heard of an intended expedition to England. In Barcelona the splendour of their welcome, they travelling incognito, amazed them. They had been, in fact, mistaken for their rightful King and one of his officers, who were expected. From Barcelona they went to Madrid, whence Alberoni sent the Earl posting all about the country after Ormonde, who was to command the invading forces. Ormonde was a kind of figure-head of Jacobite respectability. He was presumed to be the idol of the British army at the time of Queen Anne’s death; he had added his mess to the general chaos of Tory imbecility in 1714, and, in place of playing Monk’s part in a new Restoration, had fled abroad. A few of his letters of 1719 to the Earl survive: he hopes for ‘the justice which the Cause deserves,’ and when his fleet is scattered in the usual way, reports the uneasiness of James about the Earl.[7]

The Earl in Spain arranged what he could with the Cardinal, while Keith passed through France, then hostile to Spain, and met the exiled Tullibardine in Paris. Here all was confusion, the Jacobites—Seaforth, Glendarule, and Tullibardine—being deep in the accustomed jealousies. They sailed, however, and reached the Lewes, where Keith met his brother, the Earl; but here divided counsels and squabbles about rank and commissions arose. The Earl succeeded in bringing the Spanish auxiliary forces to the mainland, and was[18] for marching at once against Inverness. The other faction, that of Seaforth and Tullibardine, dallied: the ammunition, stored in a ruinous old castle on an island, was mostly seized by English vessels. News arrived that Ormonde’s fleet, sailing from Spain, had been dispersed on the seas, and the Highlanders came in very reluctantly. The Jacobites landed at the head of Loch Duich, and were posted on a hillside in Glenshiel, commanding the road to Inverness. Hence the English forces drove them to the summit of the mountain, and night fell. They had neither food, powder, nor any confidence in their men, so the Spaniards surrendered, the Highlanders dispersed, and Keith thus began his glorious military career in a style somewhat discouraging.

Lord George Murray, later the general in the Rising of 1745, was also in this rather squalid engagement. Keith was suffering from a fever, and he with his brother ‘lurcked in the mountains.’ On this occasion, no doubt, the Earl profited by the loyalty of his countrymen, among whom (says an anonymous informant of d’Alembert’s) he moved without disguise. He is even said to have been present when a proclamation was read aloud offering a reward for his apprehension. His adventures increased his love for his own people: indeed, he certainly espoused the Jacobite cause as a national Scottish patriot, not for dynastic reasons.

Keith and his brother, after ‘lurcking’ for months in the Northern wilds, escaped from Aberdeen to[19] Holland, in September 1719. Thence they made for Spain, intending to enter France by Sedan. But as they had no passports they were stopped in France and imprisoned. Keith hit on an ingenious way of getting rid of their Spanish commissions, which would have been compromising, and a letter to the Earl from the Princesse de Conti served as a voucher for their respectability, and procured their release. They reached Paris when the fever of the Mississippi Scheme was at its height. Jacobites as needy as they, the Oglethorpe girls and George Kelly, probably got hints from Law, the great financial adventurer, and founder of the Mississippi Scheme. The young Jacobite ladies bought in at par and sold at a huge premium. They thus won their own dots, and married great French nobles. Even poor George Kelly had a success in speculation. He was, at this time, Atterbury’s secretary, and being involved in his fall, passed fourteen years in the Tower. In 1745 he was one of the famed Seven Men of Moidart, but none the dearer on that account to the Earl, who never trusted him, and, in 1750, caused him to be banished from the service of the Prince. All these adventurers, Law, the Oglethorpes, Olive Trant, Kelly, and the Keiths, may have met in Paris, after Glenshiel. But the Earl and his brother did not make their fortunes in the Mississippi Scheme. They had no money, and Keith frankly expresses his contempt for the speculations after which all the world was running mad. The brothers passed to[20] Montpellier, Keith attempted to enter Spain by Toulouse, the Earl by the Pyrenees. Months later Keith tried the Pyrenees passes, and there, at an inn, met his brother, who had been arrested and imprisoned for six weeks. The King of France had just set him free, with orders to leave the kingdom, and the wandering pair of exiles went to Genoa, then a focus of Jacobite intrigue, whence they sailed to Rome, to see ‘the King, our Master.’

Jacobites lived in an eternal hurry-scurry. James had been driven from France to Lorraine; then to Avignon, where Stair planned his assassination;[8] then to Urbino, Bologna, and Rome. Sailing for Spain, in 1719, he had been obliged to put in near Hyères, and there to dance all night—the melancholy monarch—at a ball in a rural inn. Spain could do nothing for him, and he returned to Rome, whither Charles Wogan brought him a bride, fair, unhappy Clementina Sobieska, just rescued from an Austrian prison. Keith says nothing of her, but tells how, at Cestri de Levanti, his brother called on Cardinal Alberoni, now fallen from power and in exile. The Earl, with some lack of humour, wanted to tell the Cardinal all about the Glenshiel fiasco, but was informed that the statesman had no longer the faintest concern with the affairs of Spain or interest in the gloomy theme.

From Leghorn the brothers went by land[21] through Pisa, Florence, and Siena to Rome. The King, ‘who knew we were in want of money,’ sent Hay to borrow 1,000 crowns from the Pope, ‘which was refused on pretence of poverty; this I mention only to shew the genious of Clement XI., and how little regard Churchmen has for those who has abandoned all for religion.’ His Majesty, therefore, raised the money from a banker. The exiled King’s chief occupation was providing for his destitute subjects: most of his letters were begging letters.

The point for which the Keiths had been making ever since their escape from Scotland was Spain. Baffled in attempting to cross the Pyrenees, and penniless, they reached Spain by taking Rome on their way, James providing the funds with the difficulty which has been described. From Civita Vecchia they sailed back to Genoa. Now, Jacobite privateers, under Morgan, Nick Wogan, and other wandering knights, were rendering Genoa unluckily conspicuous by making the harbour their head-quarters. The tiny squadron for years hung about all coasts to aid in a new rising.

The English Minister, D’Avenant, threatened to bombard the town if the Keiths were not expelled, while, if they were, the Spanish Minister said that he would insist on the banishment of all the Catalan refugees in Genoa. To oblige the Senate of Genoa in their awkward position, Keith and the Earl departed, and coasted from the town to Valentia in a felucca, sleeping on shore every night.

It is probable that the brothers were suspected of a part in that form of the Jacobite plot which chanced to exist at the moment. From 1688 to 1760, or later, there had been really but one plot, handed on from scheming sire to son, and adapting itself to new conditions as they happened to arise. The study of the plot is, indeed, a pretty exercise in evolution. The object being a Restoration, the most obvious plan is a landing of foreign troops in England, with a simultaneous rising of the faithful. First France is to send the foreign troops; and she did actually despatch them, or try to despatch them, at various times—witness La Hogue, Dunkirk, and Quiberon Bay. When France will not stir, other Powers are approached. Sweden would have played this part, in 1718, but for the death of Charles XII. Then Spain made her effort, in 1719, with the usual results. There were hopes, again, from Russia, as from Sweden, and from Prussia in 1753.

After each failure in this kind, the Jacobites tried ‘to do the thing themselves,’ as Prince Charles said, either by assassination schemes (which Charles Edward invariably set his foot on), or by a simultaneous rising in London and the Highlands, or by such a rising aided by Scots or Irish troops in foreign service landed on the coast. From the failure at Glenshiel to 1722 this was the aspect of the plot. Atterbury, Oxford, Orrery, and North and Grey were managers in England, Mar and Dillon in Paris, while Morgan and Nick Wogan commanded[23] the poor little fleet.[9] Ormonde, in Spain, was to carry over Irish regiments in Spanish service. The Jacobites had the ship prepared years before for the expedition of Charles XII., with two or three other vessels. The gallant Nick Wogan, who, as a mere boy, had been pardoned, after Preston, for rescuing a wounded Hanoverian officer under fire, was hovering on the seas from Genoa to the Groin. George Kelly was going to and fro between Paris and London, ‘a man of far more temper, discretion, and real art’ than Atterbury, says Speaker Onslow.

When the scheme for Ormonde’s amateur invasion failed, a mob-plot of Layer’s followed it; but all was revealed. Kelly and Atterbury were seized; Atterbury was exiled, Kelly lay in the Tower, and Layer was hanged.

Keith says nothing of any part borne by his brother or himself in these feeble conspiracies. One Neynho, arrested in London, averred that the Earl Marischal had been in town on this business, in disguise, and had shared his room. Neynho merely guessed that his companion was the Earl, who certainly was on friendly terms with Atterbury. Long afterwards he wrote (1737): ‘I was told in Italy that Pope had thought of publishing a collection of familliair letters, particularly of ye Bishop; as I was honoured with Many, I sent copys of a part and parts (sic) to Pope.’ These, however,[24] could not have been political epistles. The originals must have perished when the Earl burned all his papers, as d’Alembert’s authorities report, in 1745.[10]

On the whole, it seems certain that Keith, at least, was not in the plots of 1720-22; Keith, indeed, lay ill in Paris in 1723-24, suffering from a tumour. The Earl now held a commission from Spain, which secured for him a pension, irregularly paid; but, being a Protestant, he never received an active command, except once, in an affair with the Moors. There was no harm, it seemed, in sending a heretic to fight against infidels. His great friend in Spain was the Duchess of Medina Sidonia, who was anxious to convert him.

‘She spoke to him of a certain miracle, of daily occurrence in her country. There is a family, or caste, which, from father to son, have the power of going into the flames without being burned, and who by dint of charms permitted by the Inquisition can extinguish fires. The Earl promised to surrender to a proof so evident, if he might be present and light the fire himself. The lady agreed, but the questadore, as these people are called, would never try the experiment, though he had done so on a former occasion; he said that fire had been made by a heretic, who mingled charms with it, and that he felt them from afar.’

This was unlucky, as these families whom fire[25] does not take hold on exist to-day in Fiji, as of old among the Hirpi of Mount Soracte.

The Earl had no trouble with the Inquisition, being allowed to have what books he pleased, as long as he did not lend them to Spanish subjects. ‘His religious ideas were far from strict ... but he could not endure to hear these questions touched on when women were present, or the poor in spirit: it was a kind of talk which in general he carefully avoided,’—except among philosophes.[11] Hume tells us that the Earl Marischal and Helvetius thought they were ascribing an excellent quality to Prince Charles when they said that he ‘had learned from the philosophers at Paris to affect a contempt of all religion.’ It seems improbable that the Earl was more ‘emancipated’ than Hume, but his wandering life had made him acquainted with the extremes of Scottish Presbyterianism, with the Inquisition in Spain, the devotions of his King in Rome, the levities of Voltaire and Frederick, and all the contemptuous certainties of the Encyclopédistes. The Earl rather loved a bold jest or two, in philosophic company, and his mots were not always in good taste. As a Norseman’s religion was mainly that of his sword, the Earl’s appears to have been that of his character, which was instinctively affectionate, indulgent, and charitable. If he had neither Faith nor Hope, which we cannot assume, he was rich in Charity.

It is, perhaps, no longer possible to trace all the[26] wanderings of the Earl after his brother entered the Russian service in 1728. In those years the exiles were mainly concerned about the quarrels between James and his wife, which had an ill effect on their Royal reputation in Europe. The Courts chiefly solicited for aid at this period were those of Moscow and Vienna. Spain did not pay her pension to James with regularity, and the Earl Marischal, then as later, may have suffered from the same inconvenience. This may account for his return to Rome, where he resided in James’s palace, about 1730-34. ‘He has the esteem of all that has the honour to be known to him, and may be justly styled the honour of our Cause,’ writes William Hay to Admiral Gordon, who represented Jacobite interests in Russia (Feb. 2, 1732). The little Court at Rome was as full of jealousies as if it had been at St. James’s. Murray, brother of Lord Mansfield, was Minister, under the title of Lord Dunbar, while James’s other ‘favourite’ Hay (Lord Inverness) was at Avignon out of favour, and had turned Catholic. The pair were generally detested by the other mock-courtiers. These gentlemen had formed themselves into an Order of Chivalry, ‘The Order of Toboso,’ alluding to their Quixotry. Prince Charles (aged twelve) and the Duke of York (a hero of seven) were the patrons. ‘They are the most lively and engaging two boys this day on earth,’ writes William Hay. The Knights of the Order sent to Gordon in Russia their cheerful salutations, signed by ‘Don Ezekiel del Toboso’ (Zeky Hamilton),[27] ‘Don George Keith’ (the Earl), and so on. They declined to elect Murray, because he had ‘the insolence to fail in his respect to a right honourable lady who is the ever honoured protectress of the most illustrious Order of Toboso,’ Lady Elizabeth Caryl. A number of insults to Murray follow in the epistle.[12]

All this was rather dull, distasteful work for the Earl. He received from James the Order of the Thistle (‘the green ribbon’); but, except perhaps at Rome, he would not wear a decoration not more imposing than that of the Toboso Order. Writing to his brother, he drew a pretty picture of the little Duke of York, who was fond of the Earl, and used to bring his weekly Report on Conduct to be criticised and sent on to Keith, far away in Russia. Keith was asked to comment on it, or, if he did not, the Earl was diplomatist enough to do so in his name. Prince Charles the Earl seems to have disliked from the first. He had already, at the age of thirteen, ‘got out of the hands of his governors,’ the Earl writes, and indeed the Prince’s spelling alone proves the success with which he evaded instruction. But, to please the little Duke, the Earl sent for a sword from Russia. The Duke was a pretty child, and wept from disappointment when his elder brother, in 1734, went off to the siege of Gaeta, while he, a warrior of nine, remained in Rome.

The Earl disliked the tiny jealous Court; the[28] impotent cabals, the priests who tried to convert him. Writing to David Hume long afterwards, in 1762, he said, ‘I wish I could see you, to answer honestly all your [historical] questions: for, though I had my share of folly with others, yet, as my intentions were at bottom honest, I should open to you my whole budget.’ When he wrote thus he had made his peace with England. Why he did so we shall try to point out later.

Always scrupulously honest (except when diplomatic duties forbade, and even then he hated lying), the Earl told his brother that he found the Jacobite Court at Rome no place for an honest man. He does not give details, but he seems to hint at some enterprise which, in his opinion, was not honourable. James, moreover, was sunk in devotion, weeping and praying at the tomb of Clementina. From this uncongenial society the Earl departed, and took up his abode at the Papal city of Avignon, where Ormonde now resided. He liked the charming old place, and thought it especially rich in original characters. By 1736, however, he had returned to Spain, where, as he said, he was always sure to find ‘his old friend, the Sun.’ News of the Earl comes through some very harmless correspondence, intercepted at Leyden, in 1736, by an unidentified spy.[13] Don Ezekiel del Toboso (Hamilton) was now out of favour with James, which, judging by his very foolish letters, is no marvel. He resided[29] at Leyden, corresponding with Ormonde and George Kelly. George, after fourteen years of the Tower, since Atterbury’s Plot, had escaped in a manner at once ingenious, romantic, and strictly honourable. Carte, the historian, was another correspondent; but gossip was the staple of their budgets—gossip and abuse of James’s favourites, Dunbar and Inverness. In Spain the Earl officially represented James, but his chief employments were shooting and reading. His Spanish pension was unpaid (he had a small allowance from the Duke of Hamilton), and he was minded ‘to live contentedly upon a small matter,’ he says, rather than to ‘pay court in anti-chambers to under Ministers whom I despise.’ ‘I wo na gie an inch o’ my will for an ell o’ my wealth,’ he remarks, in the Scots proverbial phrase. A Protestant canton in Switzerland would suit him best, where a little money will furnish all that he requires. ‘I am naturally sober enough, as to my eating, more as to my drinking, I do not game, and am a Knight Errant sin amor, so that I need not great sums for my maintenance.’ A Knight sin amor the Earl seems usually to have been. He must have been over forty at this time, and he had not yet acquired his celebrated fair Turkish captive. The Earl, however, had not given up all hope of active Jacobite service. ‘I propose to try if I can still do anything, or have even the hopes of doing something.’ He had a ‘project,’ and, as far as the hints in his letters can now be deciphered, it was to remove James, or, at[30] all events, Prince Charles, from Rome (a place distrusted by Protestant England), and to settle one or both of them—in Corsica!

The Earl was interested, as a patriotic Scot, in the hanging of Porteous by the Edinburgh mob. ‘It’s certain that Porteous was a most brutal fellow; his last works at the head of his Guard was not the first time he had ordered his men to fire on the people. I will not call them Mobb, who made so orderly an Execution.’

To this extent may Radical principles carry a good Jacobite! The Earl should have written the work contemplated by Swift, ‘A Modest Defence of the Proceedings of the Rabble, in All Ages.’

A quarrel with the Spanish Treasurer, who was short of treasure, ended in somebody assuring the official that the Earl was a man of honour, ‘who would go afoot eating bread and water from this to Tartary con un doblon.’ To Tartary, or near it, the Earl was to go, though he had been invited by Ormonde to Avignon. Till the end of the year 1737, Kelly and others hoped to settle Prince Charles in Corsica, with the Earl for his Minister. Marischal was expected by Ormonde at Avignon, in the last week of December, and thither he went for a month or two, leaving for St. Petersburg in March, to visit his brother. Keith had been severely wounded at the assault on Oczakow, and the Earl found him insisting that he would not have his leg amputated. The Earl took his part, and brought[31] Keith to Paris, where the surgeons saved his leg, but where he had to suffer another serious operation. Thence the devoted brothers went to Barège, where Keith recovered health. He returned to Russia, leaving in the Earl’s care Mademoiselle Emetté, a pretty Turkish captive child, rescued by him at the sack of Oczakow, and Ibrahim, another True Believer. These slaves, says a friend who gave information to d’Alembert, were treated by the Earl as his children. He educated them, he invested money in their names (probably when he was in the service of Frederick the Great), and he cherished a menagerie of young heathens, whom his brother had rescued in sieges and storms of towns. One, Stepan, was a Tartar: another is declared to have been a Thibetan, and related to the Grand Lama. The Earl was no proselytiser, and did not convert his Pagans and Turks. It is said that he was not insensible to the charms of pretty Emetté.

‘Can I never inspire you with what I feel?’ he asked.

‘Non!’ replied the girl, and there it ended.

The Earl made a will in her favour, in 1741, and she later—much later—married M. de Fromont. The love story is not very plausible, before 1741, as Emetté was still a girl when she accompanied the Earl to Paris, during his Embassy, in 1751.

The movements of the Earl are obscure at this period, but in 1742-43 he was certainly engaged for the Jacobite interest in France, residing now at Paris,[32] now at Boulogne. The unhappy ‘Association’ of Scottish Jacobites had been founded in 1741. Its promoters were the inveterate traitor, Lovat, and William Macgregor, of Balhaldie, who, since 1715, had lived chiefly in France, and was a trusted agent of James. Balhaldie’s character has been much assailed by Murray of Broughton, who was himself connected with the Association. As far as can be discovered Balhaldie was sanguine, and even of a visionary enthusiasm, when enterprises concocted by himself were in question. The adventures of other leaders, especially adventures not supported by France, he distrusted and thwarted. The loyal Lochiel and the timid Traquair were also of the Association, which Balhaldie amused in 1742 with hopes of a French descent under the Earl Marischal. Balhaldie had promised to the French Court ‘mountains and marvels’ in the way of Scottish assistance, and the Earl ‘treated his assertion with the contempt and ridicule it deserved,’ says Murray of Broughton. The Earl’s own letters show impatience with Balhaldie and Lord Sempil, James’s other agent in Paris. Thus, on February 12, 1743, the Earl writes from Boulogne to Lord John Drummond, whose chief business was to get Highland clothes wherein the Duke of York might dance at the Carnival. The Earl protests, in answer to a remark of Sempil’s, that he ‘has more than bare curiosity in a subject where the interest of my King and native country is so nearly concerned (not to speak of my own), where I see a noble[33] spirit, and where I am sensible a great deal of honour is done me, and I add, that I still hope these gentlemen will do me the honour and justice to believe that I shall never fail either in my duty to my King and country, my gratitude to them for their good opinion, or in my best endeavours to serve.’ All this was in reply to Sempil’s insinuation that the Scottish Jacobites thought the Earl lukewarm. Murray confirms the Earl by telling how Balhaldie tried to stir strife between the Earl and the Scots, who revered him, though Balhaldie styled him ‘an honourable fool.’[14]

Lord John Drummond suggested to James’s secretary, Edgar, that the Earl should supersede Balhaldie, ‘who had been obliged to fly the country in danger of being taken up for a Fifty pound note.’ Lord John’s advice was excellent. The Earl, and he alone, was the right man to deal with the party in Scotland, who could trust his sense, zeal, and honour. But James, far away in Rome, could never settle these distant and embroiled affairs. He went on trusting Balhaldie, who was also accepted by the party in England. Had James cashiered Balhaldie and instated the Earl, matters would have been managed with discretion and confidence. The Earl was determined not to beguile France into an endeavour based on the phantom hosts of Balhaldie’s imagination. Had he been minister, it is highly probable that nothing would have been done at all,[34] and that Prince Charles would never have left Italy. For Balhaldie continued to represent James in France, and Balhaldie it was, with Sempil, who induced Louis XV. to adopt the Jacobite cause, and brought the Prince to France in 1744. While his father lived, Charles never returned to Rome.

On December 23, 1743, James sent to the Duke of Ormonde, an elderly amorist at Avignon,[15] his commissions as General of an expedition to England and as Regent till the Prince should join. The Earl received a similar commission as General of a diversion, ‘with some small assistance,’ to be made in Scotland. The Earl was at Dunkirk, eager to sail for Scotland, by March 7, 1744, and Charles was somewhere, incognito, in the neighbourhood. But the Earl, as he wrote to d’Argenson, had neither definite orders nor money enough; in short, as usual, everything was rendered futile by French shilly-shallying and by the accustomed tempest. D’Alembert and others assert that Charles asked the Earl to set forth with him alone in a sailing-boat, to which the Earl replied that, if he went, it would be to dissuade the Scottish from joining a Prince so brave but so ill-supported. It is certain that d’Argenson told Marshal Saxe that the Prince ought to retire to a villa of the Bishop of Soissons, with the Earl for his chaperon. The Earl was still anxious for an expedition in force, but d’Argenson distrusted his information on all points.[35] Charles declined to go and skulk at the Bishop’s, and wrote that ‘if he knew his presence unaided would be useful in England he would cross in an open boat.’[16]

On this authentic evidence the Earl was anxious to make an effort, and Charles’s remark about going alone in an open boat was conditional—s’il savait que sa présence seule fut utile en Angleterre. But no energy, no hopes, no courage, could conquer the irresolution of France. By April Prince Charles was living, très caché, in Paris. Thus his long habit of hiding arose in the incognito forced on him by the Ministers of Louis XV. The Prince, as he writes to his father (April 3, 1744), was ‘goin about with a single servant bying fish and other things, and squabling for a peney more or less.’ He was anxious to make the campaign in Flanders with the French army, ‘and it will certainly be so if Lord Marschal dose not hinder it.... He tels them that serving in the Army in flanders, it would disgust entirely the English,’ in which opinion the Earl may have been wrong. Charles accuses the Earl of stopping the Dunkirk expedition (and here d’Alembert confirms), ‘by saying things that discouraged them to the last degree: I was plagued with his letters, which were rather Books, and had the patience to answer them, article by article, striving to make him act reasonably, but all to no purpose.’[17]

It was not easy to ‘act reasonably,’ where all was a chaos of futile counsels and half-hearted French schemes. They would and they would not, in the affair of the expedition of March 1744. We find the Earl now urging despatch, now discouraging the French, and, on September 5, 1744, he writes to James, from Avignon, ‘there was not only no design to employ me, but there was none to any assistance in Scotland.’[18] The Earl believed that the Prince’s incognito was really imposed on him by the devices of Balhaldie and Sempil, ‘to keep him from seeing such as from honour and duty would tell him truth.’

Through such tortuous misunderstandings and suspicions on every side, matters dragged on till Charles forced the game by embarking for Scotland secretly in June 1745. The Earl Marischal was the man whom he sent to report this step to Louis XV. ‘I hope,’ Charles writes to d’Argenson, ‘you will receive the Earl as a person of the first quality, in whom I have full confidence.’ The Earl undertook the commission.[19] On August 20, 1745, he sent in a Mémoire to the French Court. Lord Clancarty had arrived, authorised (says the Earl) to speak for the English Jacobite leaders, the Duke of Beaufort, the Earl of Lichfield, Lord Orrery, Lord Barrymore, Sir Watkin Williams Wynne, and Sir John Hinde Cotton. They offered to raise the standard as soon as French troops landed in England. When they[37] made the offer, the English Jacobites (who asked for 10,000 infantry, arms for 30,000, guns, and pay) did not know that Charles had landed in Scotland. D’Argenson naturally asked for the seals and signatures of the English leaders, as warrants of their sincerity. He could not send a corps d’armée across the Channel on the word of one individual, and such an individual as the profane, drunken, slovenly, one-eyed Clancarty. The Earl, on October 23, 1745, tried to overcome the scruples of d’Argenson, but in vain.[20] Clancarty, it is pretty clear, came over as a result of the persuasions of Carte, the historian, in whom the leading English Jacobites had no confidence. ‘The wise men among them would neither trust Lord Clancarty’s nor Mr. Carte’s discretion in any scheme of business,’ says Sempil to James (September 13, 1745).

Sempil was ever at odds with the Earl, who, says Sempil, ‘insists on great matters.’ French policy was to keep sending small supplies of money and men to support agitation in Scotland. The Earl did not want mere agitation and a feeble futile rising; he wanted strong measures, which might have a chance of success. ‘He can trust nobody,’ says Sempil, ‘and is persuaded that the French Court will sacrifice our country, if his firmness does not prevent it.’ The Earl was right; what he foresaw occurred. Sempil, however, was not far wrong, when he observed that the Prince was already[38] engaged, and a little help was better than none. ‘I am sorry to see my old friend so very unfit for great affairs,’ writes Sempil. The Earl had ever been adverse to a wild attempt by the Prince, as a mere cause of misery and useless bloodshed. He probably thought that no French support and a speedy collapse of the rising were better than trivial aid, which kept up the hearts of the Highlanders, and urged them to extremes.

By October 19 the Duke of York was flattered with hopes of sailing at the head of a large French force. The force hung about Dunkirk for six months, doing nothing, and then came Culloden. The Duke was prejudiced against Sempil and his friend Balhaldie, and already there was a split in the party, Sempil on one side, the Earl Marischal on the other. George Kelly returned from Scotland, as an envoy to France, but Sempil would not trust him even with the names of the leading English Jacobites. The secrecy insisted on by Sir Watkin Williams Wynne, Lord Barrymore, the Duke of Beaufort, and the others was kept up by Sempil even against Prince Charles himself. This naturally irritated the Earl, and, what with Jacobite divisions in France, and French irresolution, Marischal had to play a tedious and ungrateful part. James expected him to join the Prince, but he, for his part, gave James very little hope of the success of the adventure.[21] James himself,[39] with surprising mental detachment, admitted that the best plan for the English Jacobites was ‘to lie still,’ and make no attempt without the assistance from France which never came.

The Earl disappears from the diplomatic scene, on which he had done no good, in the end of 1745. He obviously attempted to settle quietly in Russia with his brother. But the Empress ‘would not so much as allow Lord Marischal to stay in her country,’ wrote James to Charles, in April 1747. Ejected from the North, he sought ‘his old friend, the sun,’ in the South, at Treviso, and at Venice. The Prince, in August 1747, wrote from Paris imploring the Earl to join him, for the need of a trustworthy adviser was bitterly felt. The Earl replied with respect, but with Republican brevity, pleading his ‘broken health,’ and adding, ‘I did not retire from all affairs without a certainty how useless I was, and always must be.’

At Venice the Earl entertained a moody young exile, who tells a story illustrating at once his host’s knowledge of life, the strictness of his morality, and his freedom from a tendency to censure the young and enterprising.[22]

From Venice the much-wandering Earl retired to his most sure and hospitable retreat. He joined his brother, who had now entered the service of[40] Frederick the Great. He reached Berlin in January 1748. Frederick, asking first whether his estates had been confiscated, made him a pension of 2,000 crowns. Frederick loved, esteemed, sheltered, and employed the veteran, ‘unfit for affairs’ as he thought himself. No doubt Frederick’s first aim was to attach to himself so valuable an officer as Keith, by showing kindness to his brother. But the Earl presently became personally dear to him, as a friend without subservience, and a philosopher without vanity or pretence. In his new retreat the Earl was not likely to listen to the prayers of Prince Charles, who, being now a homeless exile, implored the old Jacobite to meet him at Venice. Henry Goring carried the letters, in April 1749, and probably took counsel with the veteran. Nothing came of it, except the expulsion from the Prince’s household at Avignon of poor George Kelly, a staunch and astute friend, who was obnoxious to the English Jacobites. Since 1717 Kelly had served the Cause, first under Atterbury, then—after fourteen years’ imprisonment—in France, Scotland, and as the Prince’s secretary. He had been Lord Marischal’s ally in 1745, but Rousseau says that the Earl’s failing was to be easily prejudiced against a man, and never to return from his prejudice. Kelly’s letter to Charles might have disarmed him. ‘Nobody ever had less reason or worse authority than Lord Marischal for such an accusation; for your Royal Highness knows well I always acted the contrary part, and never[41] failed representing the advantage and even necessity of having him at the head of your affairs.... His Lordship may think of me what he pleases, but my opinion of him is still the same.’ There seems to be no doubt that the Earl had written to Floyd (whom he commends to Hume as an honest witness) to say that ‘from a good hand’ he learned that Kelly ‘opposed his coming near the Prince,’ and had spoken of him as ‘a Republican, a man incapable of cultivating princes.’ The Earl was ‘incapable of cultivating princes,’ and Rousseau esteemed him for the same. But it was under Kelly’s influence that Charles, in 1747, tried to secure the society and services of the Earl. He had been prejudiced (as Rousseau says he was capable of being), probably by Carte the historian. Years afterwards, when the Earl had disowned Charles, Kelly returned to the Prince’s household. He never had a stauncher adherent than this Irish clergyman of exactly the same age as his father. History, like the Earl Marischal, has been unduly prejudiced against honest George Kelly.[23]

About the Earl’s first years in the company of the great Frederick little is known or likely to be known. Deus nobis hæc otia fecit, he may have murmured to himself while he refused the Prince’s insistent prayers for his service, and put his Royal Highness off in a truly Royal way, with his miniature in a snuff-box of mother-of-pearl. The old humourist may have reflected that men had given lands and gear for the cause, and now, like the representative of Lochgarry, have nothing material to show for their loyalty, save an inexpensive snuff-box of agate and gold. No, the Earl would not travel from Venice in 1749 to meet the Prince.

His name occurs in brief notes of Voltaire, then residing with Frederick, and quarrelling with his Royal host. Voltaire kept borrowing books from the Scottish exile, books chiefly on historical subjects. If we may believe Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, then at Berlin, the celebrated Livonian mistress of Keith caused quarrels between him and his brother, and even obliged them to live separately.[24] The[43] Earl gave much good advice to Henry Goring, the Prince’s envoy at that time, and if he was indeed on bad terms with his brother (these bad terms cannot have lasted long), he may have been all the better pleased to go as Frederick’s ambassador to Versailles in August 1751. Thither he took his pretty Turkish captive, and all his household of Pagans, Mussulmans, Buddhists, and so forth. I have elsewhere described the Earl’s relations with Prince Charles, then lurking in or near Paris; his furtive meetings with Goring at lace shops and in gardens, his familiarity with Young Glengarry, who easily outwitted the Earl, and his unprejudiced tolerance of a perfectly Fenian plot—the Elibank Plot—for kidnapping George II., Prince Fecky, and the rest of the Royal Family. The Earl merely looked on. He gave no advice. His ancient memories could not enlighten him as to how the Guards were now posted. ‘What opinion, Mr. Pickle,’ he said to Glengarry, ‘can I entertain of people that proposed I should abandon my Embassy and embark headlong with them?’ The Earl had found a haven at last in Frederick’s favour. He was willing to help the cause diplomatically, to send Jemmy Dawkins to Berlin, to sound Frederick, and suggest that, in a quarrel with England, the Jacobites might be useful. He was ready enough to dine with the exiles on St. Andrew’s Day, but not to go further. When Charles broke with the faithful Goring in the spring of 1754, the Earl broke with him, rebuked him severely, and never forgave him.[44] He had never loved Charles; he now regarded him as impossible, even treacherous, and ceased to be a Jacobite.

The nature of his charges against the Prince will appear later. Meanwhile, as the Prince had behaved ill to Goring, who fell under his new mania of suspicion, as he declined to cashier his mistress, Miss Walkinshaw, in deference to English and Scottish requests, as he was a battered, broken wanderer, sans feu ni lieu, the Earl abandoned him to his fate, and even, it seems, officially ‘warned the party against being concerned with him.’ After forty years of faithful though perfectly fruitless service, the Earl apparently made up his mind to be reconciled, if possible, to the English Government. Though his appointment as ambassador had been a direct insult to Frederick’s uncle, George II., the great diplomatic revolution which brought Prussia and England into alliance was favourable to the Earl’s prospects of pardon.

He probably accepted the Embassy not without hopes of being able to do something for the Cause. James certainly took this view of the appointment. But the end had come. The retreat of Charles in Flanders had been detected at last by the English. The English dread of Miss Walkinshaw, and the quarrel over that poor lady, made themselves heard of in the end of 1753. By January 17, 1754, we find Frederick writing to the Earl that he ‘will secretly be delighted to see him again.’ Frederick[45] bade Marshal Keith send an itinerary of the route which the Earl ‘will do well to follow’ on his return to Prussia. On the same day Keith wrote to his brother the following letter, which shows that their affection, if really it had been impaired, was now revived:—[25]

‘17 January, 1754.

‘I’m glad my dearest brother says nothing of his health in the letter ... 27th Dec., for Count Podewils had alarmed me a good deal by telling me that you had been obliged more than once to send Mr. Knyphausen in your place to Versailles, on occasion of incommoditys; and tho’ I hope you would not disguise to me the state of your health ... yet a conversation I had some days ago with the King gives me still reason to suspect that it is not so good as I ought to wish it. He told me that for some time past you had solicitated him to allow you to retire ... and at your earnest desire he had granted your request, but at the same time had acquainted you how absolutely necessary it was for his interest that you should continue in the same post till the end of harvest, by which time he must think of some other to replace you; he asked me at the same time if your intention was to return here; to which I answer’d ... it was, tho’ I said this without any authority from you ... he told me that in that case he thought you should keep the time of your journey and route as private as possible,[46] and that after taking leave of the Court of France you should give it out that your health required your going for some time to the S. of France, that it was easy on the way to take a cross road to Strasbourg and Francfort, and after passing the Hessian dominions to turn into Saxony, by which you would evite all the Hanoverian Territories and arrive safely here. Everything he said was more like a friend than a sovereign, and showed a real tenderness for your preservation....’

Frederick did not wish his friend to run any risk of being kidnapped in Hanoverian territory, by the minions of the Elector. The Earl could not be allowed to return at once, for the clouds over Anglo-Prussian relations were clearing, while England was at odds with France, both about the secret fortifying of Dunkirk, contrary to treaty, about the East Indies, and about North America. So Frederick philosophised, in letters to the Earl, concerning the disagreeable yoke he had still to bear, and about the inevitable hardships of mortal life in general. He also asked the Earl to find him a truly excellent French cook. On March 31, Frederick offered the Earl the choice of any place of residence he liked, and expressed a wish that he could retire from politics. He foresaw the crucial struggle of his life, the Seven Years’ War. ‘But every machine is made for its special end: the clock to mark time, the spit to roast meat, the mill to grind. Let us grind then, since such is my[47] fate, but believe that while I turn and turn by no will of my own, nobody is more interested in your philosophical repose than your friend to all time and in all situations where you may find yourself.’

Frederick is never so amiable as in his correspondence with the old Jacobite exile.

At this period, Frederick gave the Earl information of Austrian war preparations, for the service of the French Ministry. Saxony and Vienna excited his suspicions. He did not yet know that he was to be opposed also to France. He was occupied with dramatists and actors, ‘more amusing than all the clergy in Europe, with the Pope and the Cardinals at their head.’ He has to diplomatise between Signor Crica and Signora Paganini, but hopes to succeed before King George has had time to corrupt his new Parliament. Happier letters were these to receive than the heart-broken appeals which rained in from Prince Charles, letters which the Earl had hoped to escape by retiring from his Embassy. Here his negotiations ‘had embroiled him with the cooks of Paris,’ but he had acquired the friendship of d’Alembert, whom he introduced to Frederick. The King thought d’Alembert ‘an honest man,’ and agreed with the Earl’s preference for heart above wit. ‘They who play with monkeys will get bitten,’ which refers to Frederick’s quarrel with Voltaire. The Earl warned the wit that some big Prussian officer would probably box his ears if he persisted in satirising his late host. ‘Rare it is,’ says Frederick, ‘to find, as in you, the[48] combination of wit, character, and knowledge, and it is natural that I should value you all the more highly.’

In May 1754, the Earl, while still pressing to be relieved from duty, was eager to undertake any negotiations as to an entente between Prussia and Spain, a country which he loved. There was an opportunity—General Wall, of an Irish Jacobite house, being now minister in the Peninsula.

The Earl left Paris in the end of June (carrying with him to Berlin poor Henry Goring, who was near death), and accepted the Government of Neufchâtel. While (February 8, 1756) Frederick’s throne was ‘threatened by Voltaire, an earthquake, a comet, and Madame Denis,’ the Earl was trying to soothe Protestant fanaticism, then raging in his little realm.

‘They will tell you, my dear Lord,’ writes Frederick, ‘that I am rather less Jacobite than of old. Don’t detest me on that account.’ It is known, from a letter of Arthur Villettes, at Berne (May 28, 1756), to the English Government, that the Earl was making no secret of his desire to be pardoned.[26] The Earl spoke of the Prince, now, with ‘the utmost horror and detestation,’ declaring that since 1744 ‘his life had been one continued scene of falsehood, ingratitude and villainy, and his father’s was little better.’

Such, alas! are the possibilities of prejudice. The Earl accused Charles of telling the Scots, previous[49] to his expedition in 1745, that the Earl approved of it. There is no evidence in Murray of Broughton that Charles ever hinted at anything of the kind. Charles’s life, from 1744 till he returned to France, is minutely known. He had not been false and villainous. He had been deceived on many hands, by Balhaldie (as the Earl strenuously asserted), by France, by Macleod, Traquair, Nithsdale, Kenmure, by Murray of Broughton, and he inevitably acquired a habit of suspicion. Lonely exile, bitter solitude, then corrupted and depraved him; but the Earl’s remarks are much too sweeping to be accurate, where we can test them. In the case of James we can test them by his copious correspondence. His letters are not, indeed, those of a hero, but of a kind and loving father, who continually impresses on Charles the absolute necessity of the strictest justice and honour, especially in matters of money, ‘for in these matters both justice and honour is concerned’ (‘Memorials,’ p. 372, Aug. 14, 1744). As to politics, James was absolutely opposed to any desperate adventure, any hazarding, on a slender chance, of the lives and fortunes of his subjects. His temper, schooled by long adversity, made him even applaud the reserve of his English adherents, and excuse, wherever it could be excused, the conduct of France, and attempt, by a mild tolerance, to soothe the fatal jealousies of his agents. No Prince has been more ruthlessly and ignorantly calumniated than he whose ‘ails’ and sorrows had converted him into a philosopher no[50] longer eager for a crown too weighty for him, into a devout Christian devoid of intolerance, and disinclined to preach.

The Earl was justified in forsaking a Cause which Charles had made morally impossible. But he believed, in spite of Charles’s contradiction, that he had threatened to betray his adherents. This prejudice is the single blot on a character which, once animated against a man, never forgave.

The correspondence of Frederick with his Governor of Neufchâtel is scanty: he had other business in hand—the struggle for existence. On July 8, 1757, he writes from Leitmentz, thanking the Earl for a present of peas and chocolate. On October 19, 1758, he sends the bitter news of the glorious death of Marshal Keith, and on November 23 offers his condolences, and speaks of his unfortunate campaign.

Probus vixit, fortis obiit, was the Earl’s brief epitaph on his brother. His one close tie to life was broken. That younger brother, who had fished and shot with him, had fought at his side at Sheriffmuir, had shared the dangers of Glenshiel and the outlaw life, who had voyaged with him in so many desperate wanderings, to save whom he had crossed Europe—the brother who had secured for him his ‘philosophic repose’—was gone, leaving how many dear memories of boyhood in Scotland, of common perils, and common labours for a fallen Cause!