A TALE OF THE CONQUEST

OF PERU

BY

George Griffith

AUTHOR OF

“The Angel of the Revolution,” “Valdar the Oft-Born,”

“Men who have Made the Empire,” &c., &c.

London

C. ARTHUR PEARSON LIMITED

HENRIETTA STREET, W.C.

1898

“Friends and comrades and cavaliers of Spain! On yonder side are toil and hunger, nakedness, the pitiless storm and the drenching rain, and it may be a grave in the unknown wilderness. On this side are ease, and pleasure, and safety; but yonder lies El-Dorado with its gold and silver and gems, the glory of conquest and the hope of dominion. Here is Panama, poverty and dishonour. Now choose each of you that which seems to you best becoming a brave Castilian. For my part I go south.”—Pizarro to his Companions.

It is a somewhat curious fact, especially in these days when books are many and subjects hard to seek, that none of our great historical novelists on either side of the Atlantic should have done for the Conquest of Peru what Lew Wallace in America and Rider Haggard in England have done for the Conquest of Mexico.

And yet surely Pizarro is as picturesque a character as Cortez, and certainly the achievements of the devoted little band of heroes who braved with him the terrors of the then unknown Sea of the South, who starved with him in Hunger Harbour and on the desolate shores of Gallo, who followed him across those colossal mountain-bulwarks which guarded the golden Empire of the Incas, who seized a conquering monarch in the midst of his victorious army and put him to death as a common criminal, bordered much more closely on miracle than did those of Cortez and his followers.

It was in this belief that I visited Peru with the intention of traversing the route of the Conquerors and obtaining those impressions, generically described as local colour, which can only be acquired on the spot. Marvellous as the story had seemed when read at home in the pages of Prescott, it became almost incredible after I had traversed the same wildernesses and scaled the same passes, many of them higher than the highest peak of the Alps, over which Pizarro had led his little army to the most wonderful conquest in the history of War.

I am only too painfully aware how far my story falls short of the splendour and wonder of its subject, but that very splendour and wonder must be my apology.

For the rest, so far as the demands of fiction have permitted, I have adhered to fact. All the characters are historical with the exception of Nahua, who lives in legend rather than in history, and the two Pallas, or wise women, who are inventions of my own. In the conversations I have reproduced as far as possible the exact words of the Conquerors, as recorded in the chronicles of their contemporaries, and if I have succeeded in making any of these wonder-workers live again, if only for an hour or two, in the reader’s mind, I shall have achieved all the success that I can venture to hope for.

GEORGE GRIFFITH.

THE LINE OF FATE

THE SUNSET OF AN EMPIRE

THE DOOM OF THE ANCIENT LAW

THE WARNING OF THE LLAPA

THE CROWNING OF ATAHUALLPA

THE CHOICE OF MANCO

THE VEILING OF THE SUN

THE KINDLING OF THE PYRE

ON THE ROAD TO EL-DORADO

HOW THE HORSES FED AT ZARAN

WHAT DE SOTO HAD TO TELL

ACROSS THE RAMPARTS OF EL-DORADO

THE OPEN GATE

IN THE CITY OF THE INCA

HOW DE SOTO PERFORMED HIS EMBASSY

THE COMING OF ATAHUALLPA

“FOR GOD AND SPAIN!”

AN INCA’S RANSOM

THE INFAMY OF FILIPILLO

“WILT THOU BE INCA OR SLAVE?”

HOW MAMA-ZULA DARED THE ORDEAL

TO THE CITY OF THE SUN

THE RETURN OF MANCO

DE SOTO’S AUDIENCE

SENTENCE OF DEATH

“SACRIFICE! SACRIFICE!”

A PAGE OF HISTORY

NAHUA’S OATH

THE HOUR OF TRIAL

A GENTLEMAN OF SPAIN

AT THE FORTRESS GATE OF YUCAY

“WE HAVE SWORN!”

FRIENDS THOUGH FOES

THE OATH OF THE BLOOD

THE BATTLE OF THE VALLEY

BELEAGUERED

ST. JAGO’S DAY

THE FIGHT FOR THE FORTRESS

The morning of the Twentieth of October, in the Year of Grace Fifteen Hundred and Twenty-seven, broke, as many another morning had done, slowly and most drearily over a little desolate island, a mere tract of sand-fringed rock, sparsely sprinkled with a few dwarf shrubs and scattered trees, lying some five leagues from the Pacific coast of Northern South America, which in those days was called Tierra Firma, and about two degrees to the northward of the Line.

As the light grew stronger under the low-brooding canopy of clouds which for many weeks had hung unbroken over the misty sea and the rain-lashed, wind-swept island, a man crawled out from under a wretched shelter of twisted boughs and ragged, sodden sail-cloth among the rocks on the western shore. He rose wearily to his feet and stretched himself with the slow, painful motion of one whose joints are stiff with wet and cold. Then he pushed the dank, black, matted hair back from his white, wrinkled brow, and his hands, thin and brown and knotted, trembled somewhat as he did so.

“Another day! Mother of God, how long is this to last? Ah, well, it is breakfast time, and one must eat even in a place like this. Come, comrades, rouse ye! it is daylight again. Perchance the ship will come to-day, if it pleases the merciful Saints to send her.”

He turned his head back towards the rocks as he said these last words, and with an effort that would have been manifest to one who heard it, raised his voice, the harsh, husky voice of a man well-nigh done to death by hunger and the sickness of body and soul that comes of bitter hardship and hope long deferred.

Then he made his way with slow, limping, dragging steps over the sloping strip of wet, much-trampled sand down to the water’s edge, and there, just out of reach of the upwash of the waves, he fell on his knees and began to dig with a little piece of stick.

Presently other figures crept out of the rocks and shook and stretched themselves just as wearily as he had done, a few of them exchanging gruff, half-murmured, half-spoken greetings, and then went and fell to at the same task until some two score or more of as woe-begone looking wretches as the unkindly Fates ever mocked at in their misery were scattered along the shore, grubbing on their knees in the spongy sand amidst the spume of the out-going waves for the sand-worms and crabs and such other shellfish as relenting Fortune might deign to send to them for their morning meal.

There were high-born gentlemen of Spain among them, haughty gallants who had lorded it with the proudest in Seville and Cordova and Madrid, who would once have run a man through the body rather than yield him an inch of the footway, who had feasted and drunk and danced and diced and made love till only a remnant of their fair estates was left to them, and that they had staked on one last throw with Destiny—life, and honour, and every hope they had against a share of the fairy gold of El-Dorado, long dreamed of and never found.

There were rude sailors, too, and outlawed adventurers, cut-throats and cut-purses, criminals fleeing from justice, and debtors from their creditors; husbands who had wearied of their wives, and scapegrace sons who had been driven from the homes they had dishonoured—and here they all were, ragged and starving, racked with ague and smitten with scurvy, scraping shellfish and worms out of the sand wherewithal to make the pangs of famine a little more endurable, for the hand of misery had fallen heavily upon them and crushed them all down level with the beasts that eat and take no thought for the morrow.

On a little plateau among the rocks, some twenty feet or so above the beach, a rude flagstaff had been fixed, propped up by a cairn of stone, and from the top of it flew a tattered flag that had once borne the proud arms of Spain, Mistress of the West and heiress of all its unknown wealth and mysterious glories, and, pacing with slow steps up and down the little platform in front of the cairn, was a man whose worn and work-stained dress distinguished him but little from the wretches who were digging on the sands below him.

Though but a few years past middle age the storm and the stress of a long life of travail might well have passed over his stooping shoulders and down-bent head. His long black hair and ragged beard were streaked with grey, and his face was pinched with hunger and seamed and lined with the furrows of ever-present care; and yet his eyes, as he raised them every now and then to gaze out over the misty sea, as though striving to pierce the dense cloud-curtain in which sky and water were lost on every side, were still bright and proud and fearless as befitted the leader of the forlornest hope a soldier of fortune had ever led.

And yet his thoughts, as he paced that narrow strip of rock and muddy soil, were dark enough to have quenched the light in the eyes of most men, for they were thoughts of long and bitter toil which so far had brought no guerdon save failure and debt and dishonour.

He was thinking of that ill-starred Darien expedition, with its plague and famine and ruthless slaughterings, which had been the grave of so many golden hopes; of the gallant high-hearted Vasco Nuñez de Balboa whom he had watched toilfully climbing the hills from whose summit he, first of all the men of the Old World, was to behold this Sea of the South over which he was now looking, hoping against despair for Almagro’s ship to come and end the weary weeks of waiting; and then he thought of his own black treachery which had sent Vasco to his death in obedience to his own unspoken resolve to strike all men from his path who bade fair to get to the Golden South before him.

Then his thoughts shifted on to his first expedition southward from Panama, and he reviewed one by one with unsparing exactness the long succession of labours and disasters that had daunted well nigh every heart but his. He thought of his little, crazy, overloaded ships struggling against storms and contrary currents; of the pestilential swamps and fever-haunted forests through which he had led his ever-dwindling little band of followers, and of the twenty-seven men who, one by one, had starved to death under his eyes in Hunger Bay—just as those companions of his down yonder must soon starve if help did not come.

Then at length his thoughts took a brighter hue as they turned back to the day on which that young naked savage lad, son of the cacique Commogre on the mountains above Darien, had laughed at the Spaniards for quarrelling about a few pounds’ weight of gold and, pointing to the southward, had told them of the unknown sea and the lands that lay along its borders where gold was as common as the stones by the wayside and silver as the wood in the forests; and lastly he remembered how he himself had had that brief glimpse of El-Dorado at Tacamez which had lured him on to this, his second, journey which had ended here on the desert shores of Gallo and in the pitiless clutches of famine and despair.

Surely thoughts like these were enough to shake the heart and turn back the steps of many a man who might well yield to such ill-fortune and yet still be accounted brave; but it was not such a man who stood beside the flagstaff-cairn on Gallo and stared out in defiance of Fate itself over that dreary sea and into those all-circling glooms. If he had been he would never have written the name of Francisco Pizarro in letters of blood and flame across the Western World beside that of Hernando Cortes, and, though he knew it not, ere that day’s gloom had deepened into the darker gloom of night, he was to show by a few brief words and one all-decisive act what manner of man he truly was.

The diggers on the beach had ended their task and were roasting the wretched fruits of their labours over a few smoky fires of mouldering sticks in the driest places among the rocks. But Pizarro, still seemingly lost in his thoughts, made no motion to join them at their meal, and presently a man whose short, sturdy, strong-built frame seemed to have defied so far both famine and sickness, came with short, active steps up on to the platform, carrying a drinking-can in one hand and a wooden platter in the other.

“Since you did not come to your breakfast, Señor Capitan, I have brought it to you,” he said in a cheery voice, as Pizarro saw him and came to meet him. “ ’Tis poor fare enough, but as good as this God-forgotten wilderness affords. This is almost the last of the wine, but the fish is passable, though the biscuit would be better if there were more bread and less mould.”

Pizarro took the platter but put back the proffered can, saying with a smile that was strangely soft and kind for such a man as he—

“Nay, nay, good Ruiz. I thank you for your care of me, but I have no need of the wine, I who am still the strongest here, saving perchance yourself. Take it back and let the sick have it. Water is good enough for me. Nay, nay, man, I tell you I will not have it. Take it away and bring me a stoup of your best water instead.”

“Ever the same, Señor,” said the Pilot—for it was he, Bartolomeo Ruiz, first Pilot of the Southern Seas, who had brought the future Conqueror his breakfast in such homely fashion—“ever the same, caring more for the meanest wretch that has scurvy in his bones than for the life that is now everything to us. Still I do your bidding for its kindness’ sake, praying, as I ever do, that Our Lady of Mercies may wait no longer to reward your goodness with the fortune it deserves. Ha! by the Saints, what was that?—the sound of a gun from the sea! Now, glory to God and Our Lady—there Almagro comes at last! Said I not ever that he would never leave us in our need?”

As Pizarro’s longing ears caught the thrice-welcome sound that came booming out of the mist to seaward, a bright flush leapt into his thin, sallow cheeks, and he stretched out his hand and said in a voice that had a clear, strong ring of joy in it—

“Bring back the wine, Ruiz! The sick will have better than that ere long, so we’ll pledge each other, you and I, old friend, to the end of our troubles and a fair wind to El-Dorado!”

Before the can was dry the men of the forlorn hope had forgotten their hunger and their weakness and had started at the sound of the gun to scramble up the rocks to get a better sight of the long-expected, oft-despaired-of argosy of their hopes which they now so fondly believed had come to their aid at last.

Men who had scarce been able to crawl down to the water’s edge an hour before now ran nimbly as schoolboys up from the beach to the plateau, and Pizarro’s heart, ever as soft towards his companions-in-arms as it was hard towards his enemies, bled for them as he watched them, lean and ragged and crippled with disease, staring with hunger-hollowed eyes out into the mist which still hid the vessel from them. But the next moment the instinct of command returned to him, and he said in a loud, cheery tone—

“We must do something else than stare at the sea, comrades, if we don’t want Almagro to sail past the island in the mist. Uncover the gun and bring up some powder and a length of match so that we may answer their signal.”

They ran to obey him like men who had never known an hour of sickness. Beside the cairn was a heap of sail-cloths and well-tarred canvas which, when stripped off, revealed a mounted culverin, a Spanish piece capable of throwing a ball of two or three pounds in weight. It was scarcely uncovered before the powder arrived. The gunners loaded with a good charge, well rammed home. Then Pizarro took the match from Ruiz, who had kindled it, and fired it with his own hands. As the echoes of the report rattled away among the rocks every man on Gallo strained his ears to catch the answering sound from the sea. After a space of about a minute it came.

“She is yonder!” cried Ruiz, pointing out into the mist. “I saw the flash. There goes another gun, and there she comes like a ghost out of the clouds. Now, glory to the Lord of Hosts, who has heard the voice of our distress! On your knees, brothers, and give thanks, for the time of our misery is ended!”

Then down he went on his knees with hands uplifted, and, save Pizarro, every man followed suit, and there arose from that wild place as strange a sound of mingled praise and prayer as ever had risen from earth to Heaven. Men with shrill, cracked voices sought to raise the triumphant strains of the Te Deum, others, hoarse and husky, broke out into the Magnificat, and others again wept and laughed by turns, bringing forth nothing but a babble of words mingled with shrill cries and broken by sobs, until suddenly the quick, stern voice of Pizarro broke through the babel, bringing every man to his feet.

“Ruiz, Pedro de Candia, Alonso de Molina, come hither!”

The three men went to him where he stood apart from the rest by the flagstaff. They saw that the flush had died out of his cheeks, that his brows were frowning, and his eyes dark with an evil foreboding. He turned and faced them and said, in the hard, stern tones that they had so often heard from his lips in the moments when all others about him had despaired—

“We give thanks too soon, I fear me, comrades. That is not Almagro’s ship. She is twice the size, and look yonder—behind her, there comes another out of the mist. Think you that fortune has so smiled upon Almagro that he went away with that poor little caravel of ours to return with two such ships as those? Nay, unless my heart is lying to me, not friends but enemies are yonder—enemies to our high enterprise, if not to our persons, for ere long you will learn that those ships come from Pedro de Arias, and not from Almagro and de Luque.”

“The good Saints prove you wrong, Señor!” said the tall and, in spite of his rags, still graceful-looking cavalier who had answered to the name of Alonso de Molina. “Yet though they should have come to take us back to Panama by force, yet forget not that there are true hearts among us who have sworn to follow you, and will, though you lead us to the mouth of the Pit itself.”

“Well spoken!” said he, also a knight of goodly stature and presence, who had come when Pedro de Candia was called. “Though there be but half a score of us that remain true, we will not forget what Almagro said when he left us, ‘better to roam a free man through the wilderness than to lie in chains in the debtors’ prison at Panama.’ What say you, Señor Capitan? Shall we get the arms out?”

Pizarro thought for a moment, and then he raised his head and, with a glance at the ships which were now close in shore, he said—

“Yes, get them out. Let us receive them as soldiers and gentlemen of Spain, whatever errand they come on; but be that what it may, I swear by my good Saint, St. Francis, and all the host of Heaven, that if ten, ay, if but two good men stand by me, I will stop here and wait Almagro’s coming, or such other means as God’s mercy may send us to prosecute this our enterprise to the end. Now, there comes the boat. Let us go and arm ourselves and receive them in what poor state we may.”

“And three swords, if no more, shall be used this day to help you to keep that oath of yours, Señor, if need be,” said Ruiz, as they went downward toward the beach, and the others said with one voice—

“Amen to that!”

On the beach Pizarro gave his orders with the quick, clear decision of a man to whom command is second nature, and arms and armour were taken out of their hiding-places, where they had been buried out of reach of the rain, and furbished up and donned on weak and famine-worn limbs with hands that trembled half with weakness and half with the excitement of new-born hope, for Pizarro had strictly enjoined his three companions to say nothing of his fears to the others.

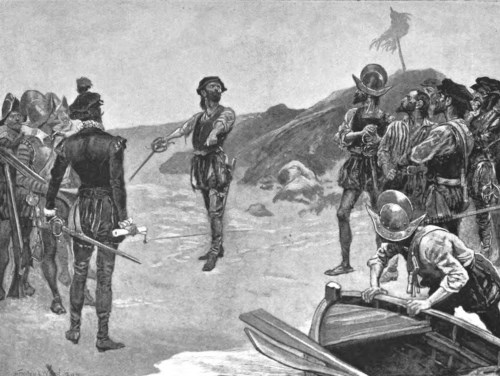

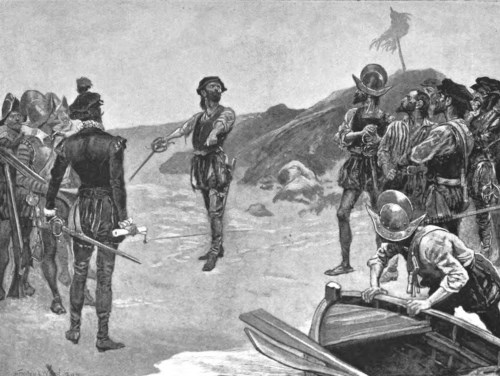

Meanwhile a boat, with the flag of Spain trailing from her stern, was slowly making its way from the larger of the two ships to the shore. As her keel touched the sand a score of men, forgetting their discipline, as they well might do in such a moment, ran into the water and took hold of her gunwales, striving to draw her up, at the same time crying their welcomes to those they took for their deliverers; but Pizarro, with the chief and better-born men of his company, stood aloof on the shore, only saluting the new-comers in a grave and soldierly fashion.

When the boat was well aground, a tall, lean man, whose bright arms and handsome dress looked splendid in contrast with the wretchedness of the Men of Gallo, came and stood up in the bows, and, unrolling a parchment that he held in his hand, bowed to those about him and, with no further greeting, straightway began to read—

“From his Excellency Señor Don Pedro de Arias, by the Grace of God and the favour of his most Puissant and Catholic Majesty Charles the Fifth of Spain and the Netherlands and Lord Paramount of the Indies, to Francisco Pizarro, Bartolomeo Ruiz, Pedro de Candia, Alonso de Molina, and all other faithful and obedient servants of His Majesty aforesaid, now on the Island of Gallo in the South Sea, Greeting!

“These are to inform you that the said Don Pedro de Arias, having received certain complaints from persons now serving in an expedition under the command of the said Francisco Pizarro, and being well aware how great loss and suffering hath been occasioned by the ill-conduct and disaster of the said expedition, and having well weighed these matters in his council at Panama, hath sent his lieutenant, Don Lorenzo Tafur, with two ships, to bid the said Francisco Pizarro, and those with him in the Island of Gallo, to return in the said ships with all speed to Panama, that an account of the lives and treasure lost in the said expedition may be faithfully rendered to him, and that the precious lives of his Catholic Majesty’s faithful subjects may no more be endangered and wasted on the fantastic and chimerical schemes of the said Francisco Pizarro and his associates.

“Given under my hand and seal in the Government House at Panama, this the eighth day of October, in the Year of Salvation, one thousand five hundred and twenty-seven—

“For the King,

“Pedro de Arias.”

When he had finished his reading the Lieutenant folded up his parchment and sprang to the land. As he did so some of the Men of Gallo raised a cheer, but others stood silent, looking at Pizarro as though wondering what he would say to this. He took a couple of steps forward to meet Tafur, and then saluting him with a courtesy which then as ever belied the baseness of his birth, drew himself up, and with his hand on his sword-hip looked him in the face and said—

“That is a cold and formal greeting, Señor, to bring to men who have spent all they have save their lives in the effort to win new lands and new nations for God and His Majesty; but such as it is, here is my answer to it. I, for one, having spent so much, am resolved to spend more, even to the life which is all that is left to me, before I will turn back. Having gone thus far, God and the Saints helping me, I will go to the end. The rest of my comrades can speak for themselves, but I go on.”

“And I! and I! and I!” cried Ruiz and Candia and Molina with one voice, drawing their swords and pointing them heavenwards in token of their oath.

Tafur drew himself up facing them, staring at them half in anger and half in wonder, for it seemed to him incredible that men who had manifestly suffered the utmost extremities of famine and misery could still have so bold a spirit left unbroken in their breasts. Then he said angrily, and yet not without a touch of pity in his voice—

“But, Señors, this is disobedience—nay, more, it is rebellion, since you are commanded to return in His Majesty’s name.”

“But not by His Majesty’s voice or under his hand and seal!” said Pizarro, cutting his speech short with an impatient gesture. “We be true and loyal subjects of the king, but Pedro de Arias shall have no obedience of mine in this matter. He is a partner with me in this venture, and has pledged his word to the carrying out of it. Moreover, it is not for our sakes that he bids us return, but because he wants good Spanish men and good Spanish swords to do his own work in Nicaragua. So, once for all, Señor, I will not go back, though I will seek to coerce none to stay with me.”

“Then, Señor Capitan,” replied Tafur, bowing as though unawares in respect to the greatness of this man’s heart, which could thus lift him above his miseries, “since I have neither the authority nor the will to use force against you, I will but say that all who will shall come with me, and that all, if any shall be so mad and blind to their own interest, who shall elect to stay with you may do so.”

“And if a sufficiency shall nevertheless elect to stay,” said Pizarro, looking round with a smile on his wretched followers, “will you not give me the smallest of your ships——”

“No, Señor, no!” replied the Lieutenant, stopping him as soon as he saw his drift. “Not a ship, not a boat even will I give to encourage you in your disobedience. I was not sent here to help you waste more lives and treasure in this mad enterprise of yours. If you elect to stay, you shall stay, but I will strain my authority no further. So now decide quickly and let me be gone, for there is food and drink on yonder ships, and clothes and shelter for those who will have them, and I will not keep starving and naked men longer without them than I can help.”

“Then that shall be soon decided!” said Pizarro, drawing his sword and going apart a little to where there was a smooth stretch of sand. Then with his sword-point he drew a long line from west to east, and, standing on the northern side of it, he pointed towards the south with his blade, and turning to the whole company, which had followed him to learn the meaning of what he did, he said in a clear, strong voice—

“Friends and comrades and cavaliers of Spain! On yonder side are toil and hunger, nakedness, the pitiless storm and the drenching rain, and it may be a grave in the unknown wilderness. On this side are ease, and pleasure, and safety; but yonder lies El-Dorado with its gold and silver and gems, the glory of conquest and the hope of dominion. Here is Panama, poverty and dishonour. Now choose each of you that which seems to you best becoming a brave Castilian. For my part I go south.”

And with that he stepped across the line. There he faced them, one man daring Fate which had already almost done its worst upon him, still defying its further terrors. The others, both his own men and Tafur’s, stared at him for a space, stricken dumb with wonder and reverence for him. Then Ruiz broke loose from the group amidst which he stood, and saying simply: “Señor Capitan, if none other follow you, I will!” walked across the line. Close following him came Pedro de Candia with his drawn sword across his shoulder, marching in silence like a soldier at parade. Then Alonso de Molina, who crossed himself and said—

“God must be with such a man as that. Come, comrades, yonder is the only road for a brave man!”

And after him there came one by one eleven others, of whom some crossed the line in silence without looking back, while some prayed and others laughed, and others went sideways, beckoning to those behind as though mocking their lack of courage; but when the fifteenth man, who was named Juan de la Torre, had gone over, the rest hung back and not a man of them moved, but each looked at the other and then at the little group beyond the line and then at the ships.

And so the Line of Fate was drawn, and so was the wheat divided from the chaff and the gold of true valour from the dross, and thus did Francisco Pizarro, the base-born captain of adventurers, draw his sword in the face of a frowning destiny, and with it trace on the shifting sands the line of a mighty nation’s fate, and thus did he step over it, he and those who were faithful to him, out of the obscurity of his former life into the light of a fame that shall last while the world endures.

That afternoon Lorenzo Tafur sailed away with his ships and the faint-hearts who were not found worthy of great deeds; but after much argument and altercation he had been persuaded to leave a small portion of stores on the island, and he also took with him Bartolomeo Ruiz, the Pilot, charged with urgent messages to Almagro and De Luque, through whose hands came the funds that had been furnished by the Licentiate Espinosa for this and other expeditions, telling them of the resolution come to by Pizarro and his companions, and praying them to do all that in them lay to bring the succour they so sorely needed.

So the ships sailed away northwards and were lost in the mists and clouds, and the little band stood together on the rocks of Gallo watching them go until they had faded like ghosts into the gloom and the shadows drew closer round them and the night fell dark and drear over the desolate spot.

But, though the little band of heroes knew it not, far away to the southward, above the clouds which lay over them like a pall, the new-risen moon was shining in a clear and cloudless sky, gemmed with thousands of stars more brilliant than they had ever seen, over gleaming fields of spotless snow and soaring peaks of everlasting ice, through the midst of which they were one day to march to the long-dreamed-of El-Dorado and to the glory and the shame that was to be the reward of their valour and their sins.

The sun had set over Quito, “the City of the Great Ravine,” but high above the night that had fallen upon the valley rounded tops and pinnacles of rock, gleaming domes of snow and shining minarets of ice were glowing with rosy fires changing every moment the wondrous hues which they borrowed from the light that seemed to stream across them from an unseen source. The unclouded sky was still a fathomless sea of radiance, and, high above all its attendant peaks, the mighty dome of Chimborazo towered up from the gloom into the light, crowned with a canopy of smoke whose rolling clouds seemed like a glorified chaos of light and darkness, of the sombre shadows and brilliant, many-coloured radiance, suspended between heaven and earth.

On a couch of the softest textures ever woven by human hands, draped over a framework of precious woods clamped and in a great part overlaid with gold, Huayna-Capac, the last of the long line of Incas descended from the Divine Manco and his sister-wife Mama-Occlu, son and daughter of the Sun, lay dying. The heir of the great Inca Yupanqui, during his long life of unsparing conquest and yet wise and most merciful rule, had extended the empire of the Children of the Sun until, from the burning regions of the North, beyond the central line of the earth, to the arid deserts of the far South, and from the trackless forests of the East to the shores of the Western sea, all the lands and peoples of Tavantinsuyu1 owned, with gladness and without question, the glory of the Rainbow Banner and the just, yet rigid, sway of the Son of the Sun.

All that the valour of his soldiers, the wisdom of his councillors, and his own imperial genius could do had been done, and in all the world there was no other empire whose ruler was so completely all-powerful and whose subjects were so peaceful, prosperous, and contented as his were.

It was an empire at its zenith. It had reached that acme of military strength and social organisation beyond which, as the history of the world would seem to tell us, the Fates who govern human destiny do not permit a human society to develop.

Over an extent of a thousand leagues from north to south, and for four hundred leagues from east to west, in a land which rose from the deserts and torrid valleys of the Pacific coast through infinite gradations of climate to the eternal winter of mountain solitudes soaring far beyond the clouds into the realms of everlasting frost, and from the tropical valleys of the eastern and western slopes where Nature laughed in unrestrained luxuriance to the vast, treeless plains of grass which lay high above the limit of cultivation, walled in by the tremendous rock-ramparts which were crowned with the snowy diadems of the Andes, there was not a man who had need to take thought for the things of to-morrow, not one who did not know that if he fulfilled his duty to the State of which he was a unit, all that he could demand from it would be freely and ungrudgingly granted.

There had never been such a society upon earth before, it might be that there would never be such again, and now the work of twenty generations was finished, and the jealous Fates, as though unwilling that too much felicity should be the lot of man on earth, were looking down with angry eyes upon its perfection and conspiring even in the very centre of its power and glory to work its destruction. Nay, they were even gathered, pitiless and vindictive, around the death-bed of the dying warrior and statesman whose hand in the fulness of its strength had placed the coping-stone on the stately and symmetrical structure of the Empire of the Incas.

On the rich, many-coloured furs which carpeted the cedar-boarded floor of the golden-walled, silver-ceiled room lit with silver lamps hanging by chains of gold, stood by the bedside in an attitude of attendant deference a very old man clad in the splendid robes which distinguished the priesthood of the Sun. His arms were crossed over his breast and his bared head was bowed, though every now and then the lids of his downcast eyes were raised and he looked anxiously at the face of his sleeping lord as though he were waiting for him to wake—perhaps even wondering whether he would ever wake again.

At last a deeper breath filled the breast of the sleeper and raised the embroidered coverings. A long sigh broke the silence of the death-chamber, and the eyes of the Inca opened. The priest took a soft step forward, and then he bent his head still lower and waited for his lord to speak.

“Are you still waiting for the end, Ullomaya? It is a long time coming, is it not? Yet it may be still longer, for my sleep seems to have given me new strength, and it may be that I shall even now see another day.”

“May He who is above the Gods grant it, Son of the Sun and Lord of the Four Regions!” the priest answered, raising his hands palms outward and lifting his face to the ceiling, and making with his lips the mute sign which the Children of the Sun made when the name of the Unnameable was in their hearts. “For your Father, the Sun, has put it into the heart of his servant to say words to you that should not be left unsaid in such a solemn hour as this.”

“Then say them, Ullomaya, and say them quickly, for neither you nor I know at what moment the summons may come to me to take my place with my fathers in the Mansions of the Sun. Speak freely, therefore, yea, even though you would speak on things forbidden.”

“It was even of a thing forbidden that I would speak, Lord!” the priest replied, taking another step forward and stretching out his hands as though in entreaty. “It was even to seek that permission that I came.”

The Inca’s eyes closed for a moment, and then he opened them again and said with a smile, half of weariness and half of indulgence—

“Say on, then, old friend and good counsellor. For your sake the law of my lips shall be broken for the first and the last time. What is it? Not that which is already resolved? Do not tell me it is that, for the decree is already gone forth, and the last act of my life cannot be the revoking of words that an Inca’s lips have spoken.”

“Yet is it even that, Lord,” said the priest more boldly; “for in this matter only in all the long years that I have served you you have listened to my counsel and taken that of others. Your footsteps are approaching the thresholds of the Mansions of the Sun, and mine are not very far off. Once past them we shall stand side by side in the presence of our Father, and each must give to the Divine Manco an account of that which he has wrought in the land that he gave to our fathers. And you, O Lord, would go into that sublime presence with the guilt of a disobedience lying heavy on your soul.”

As the priest said these last words in a low and yet unfaltering tone a light seemed to kindle in the dying despot’s eyes, a faint flush rose into his cheeks, and his hands caught nervously at the bed-coverings as he said with the ghost of the voice that had once rung high above the clamour of battle—

“Only one man in the land of Tavantinsuyu dare say that to me, Ullomaya, and even he scarce dare say it to me save on my death-bed.”

“The Son of the Sun is still Lord of the land, and his word could still send me to the doom of those who disobey!”2 said the priest, crossing his hands over his breast again and bending low before his master.

“Nevertheless, for the sake of the love I bear you, say on!” said the Inca.

Then the priest drew himself up again and said—

“It is not my will that speaks, Lord, but rather the spirit of my duty to the Children of the Sun and you, their Lord. By the might of your arms and the wisdom of your counsel you have enlarged the borders of the empire that your fathers gave you and brought many new peoples under its sway. Your throne has been higher, and your rule wider, than those of any that have gone before you. In this you have done well and fulfilled the commands that have been obeyed by twenty generations of the Children of the Sun, yet the last act of your royal power will undo in its evil all the good that you have accomplished.

“When the Divine Manco left the world to return to the presence of his Father he left, as his last charge, the command to all who should come after him to keep the empire that he had given them one and indivisible for ever.

“Yet, by your last act, you have divided it. Nay, more, you would set on the throne of the North a prince whose blood is not of the pure and holy strain, and you have taken the sceptre of empire far away from the City of the Sun, and in so doing you have made those to lie who said that the Son of the Sun can do no wrong. Lord, it is not yet too late to undo this and save the empire of your fathers from the doom that will surely fall upon it when the laws of its Creator cease to be obeyed.”

“And would you have me disinherit my son Atahuallpa, the darling of my old age, the gallant lad who has followed me to battle and fought by my side, and who, under my own eyes, has grown to be a man and a warrior, while Huascar, to whom you would give the lands that are his by right of birth, has been dallying with his women and his courtiers amidst the delights of Cuzco and Yucay, never giving anything but an unwilling hand to the work that I have spent my own life in? Would it not be a greater wrong to do this—to rob my warrior-son of his right?”

“The laws of the Divine Ones are above all human rights, Lord!” the priest replied, looking steadily into the eyes of the man whose word could send him instantly to a death of torment. “Though I never speak other words on earth, though to-morrow’s light may shine upon my ashes, yet I must speak what long and lonely vigils and many ponderings on this matter have taught me.

“The empire that the great Yupanqui gave you, and which you have made so mighty and so glorious, can only subsist as one. To divide it is to destroy it, for it is not in the hearts of princes to live at peace when their borders touch. Nay, more, Huascar, your son and your firstborn, is of the Divine descent, pure and undefiled, and the ancient laws will tell him that the realm is his from end to end and from the mountains to the sea, and think you not that our Lady, his mother, and the nobles of the Blood will not urge him to claim his right when the hand of Death has taken the borla from your brow?

“Moreover, Atahuallpa, the Prince of Quito, though the son of their conqueror, has yet also in his veins the blood of a conquered people, and many generations are needed to wipe the stain of defeat away. So when the grasp of your own strong hand is loosed, though there may be peace between them for a season, a time shall come when these two princes shall draw the sword upon each other and a war of brother against brother and of kindred against kindred shall desolate the land that your wisdom and strength have blest with prosperity and contentment.

“Yet a few more words, Lord, and I have done. On those who see the portals of the Mansions of the Sun open before them there shines a light which no eyes but theirs can see. May our Father, the Sun, grant even now that in the radiance of this light you may see into the future that was hidden from you before, and save while there is yet time your children and your people from the destruction which you would bring upon them!

“These are the words of truth, Lord, for while you have fought and striven I have watched and thought and prayed, and out of the silence of the night there have come voices from the stars that rule our fate, and this is the lesson that they have taught me.”

The Inca heard him in silence to the end, now frowning and now smiling sadly, and when he had finished he lay in silence for a while with his eyes closed, and so still did he lie that the priest at last softly stole close up to the side of the bed and leant over him, wondering whether he was still alive. Then his eyes opened again, and he said in a soft, clear voice and with a smile on his pale lips—

“Nay, Ullomaya, I am not dead yet, my friend, and your words have sunk deep into my heart. I have seen the light that shines over the threshold which I must soon pass, and it has shown me the way of right and justice. The ancient laws shall not be broken. It shall be as you say. Huascar shall reign after me, supreme lord of all the land, and Atahuallpa shall be Prince of Quito under him.

“Go now and summon the princes of the household and the priests and curacas of the provinces that I may make my will known to them while yet I have strength to do it, for the hand of Death is already upon me, and the light of the lamps is growing dim in the brighter light that comes from beyond the stars. But first send Zaïma, my wife, and Atahuallpa, my son, to me that I may tell them.”

The priest bowed low before his lord again, and then, murmuring words of praise and thankfulness, went quickly from the room to do his thrice-welcome errand. For a few minutes the silence of the splendid death-chamber was unbroken save by the faint sound of the dying Inca’s breathing. Then the thick woollen curtains which covered the door were drawn aside, and a woman, tall and of imperial carriage, and still fair to look upon, with the relics of a beauty that had once been peerless, came into the room followed by a stalwart, splendidly robed youth who could have been none other than her son.

As they entered the Inca opened his eyes, and with the hand that was lying outside the coverings of the couch he beckoned to them to come near. They went and stood by his bedside, and he told them in the brief words of a man who knows that he has not many words to waste that which he had summoned them to hear.

For a moment they stood silent and motionless, looking each at the other and then at the Inca who lay watching them and waiting for them to speak. Then suddenly a deep flush of anger burnt in the woman’s cheeks and a fierce light leapt into her eyes, and with a swift movement she laid her hands over the dying Inca’s mouth and nose and pressed his lips and nostrils tightly together.

His eyes opened widely into a stare of horror. There was a brief, convulsive movement under the covering, and then the glaze of death dimmed the staring eyes, and when the high priest came back, followed by the chief princes and nobles of Quito, Zaïma the Queen was lying wailing over the dead body of her husband and her Lord, and Atahuallpa, Inca of the North, was cowering by the bedside with his face buried in his hands and his body trembling and shaking with sobs.

At the same moment, far away to the northward and westward, a man was drawing with his sword-point a line along the sandy beach of the desolate island of Gallo, and in the years to come, though neither he nor the son of the murderess knew it, the steel of that same sword was destined to cleave its way to the heart of the great empire which Huayna-Capac would have made impregnable but for the hand of his queen which robbed him of the last half-hour of his life.

Ullomaya and those who followed him stopped suddenly on the threshold of what was now in truth the death-chamber of the Inca, and bent their heads and remained for a moment in respectful silence. Then the High Priest of the Sun went forward to the bedside and spoke to the prostrate woman, saying—

“Alas, I see we come too late, for our Lord is already standing in the bright courts of the Mansions of the Sun, and yet not too late, since before he departed he spoke the words of wisdom and comfort for his people. Is that not so, O Queen?”

The self-widowed queen rose to her feet as she heard him speak, and faced him with clenched hands, head erect and somewhat thrown back. There were no tears in the great deep dark eyes which burnt angrily under her straight, black brows, but the pale olive of her cheeks and brow looked a ghastly grey under the yellow fringe of the Llautu which denoted her rank, and her lips, of wont so red and fresh, though she had been a mother for twenty years, were pale and drawn and twitched somewhat at the corners as though betraying the workings of some fierce passion within her; and when she spoke, her voice, which had been the sweetest that had ever spoken the liquid speech of the Valley, rang harsh and angry on the silence of the chamber.

“Yes,” she said, “he is dead, my lord and master, the love of my youth and the honour of my age—he is dead! and as thou sayest, priest, he died with words of wisdom and comfort upon his lips. With his last breath he granted my prayer that he would not disinherit his son or take the empire of Quito away from the House of my fathers and give its children to be subjects to the men of the South.

“This is not what you have come to hear, you who vexed the last hour of my Lord’s life by seeking to turn his footsteps from the path of justice as they were approaching the threshold of the Mansions of the Sun, but it is said beyond recall, and thou, Ullomaya—High Priest of the Sun and man of the Divine Blood as thou art—art yet a traitor, for Atahuallpa is, from this hour forth Inca and Lord of Quito, and thou hast sought to rob him of his inheritance and make him the vassal of Huascar. Go forth, now, for thou art not fit to look upon the face of thy dead Lord!”

As she said this, Zaïma the Queen, with a swift movement of her arms, threw the bright-hued mantle that hung from her shoulders on to the couch so that it fell over the dead Inca’s face, and then her right arm went out, pointing with extended forefinger to the door.

The high priest shrank back instinctively before the imperious gesture, and the little throng of priests and nobles gathered about the doorway, parted, leaving the way clear for him, for in their eyes he was already accursed, since he stood charged by the lips of the all-powerful queen-mother of a crime so great that no man of the Divine Blood had ever been guilty of it before him.

His deep knowledge of his people and their laws told him that any words of defence would be useless and worse than useless. So, throwing himself for the moment into the posture of supplication, he made a silent invocation to the Unnameable, whose name he would not utter even in a moment so solemn as this, and then turned and went slowly towards the door; but before he reached it a hand was laid heavily upon his shoulder and a grip like the clutch of a condor’s talon held him motionless.

Atahuallpa had sprung erect from the place where he had been cowering by the bedside. The horror that had shaken his soul had passed. At the sight of his mother’s imperial gestures, and the sound of her fierce and pregnant words, the warrior spirit and the fierce pride of the despot had awakened within him. He had accepted his destiny, and so sanctioned the crime which had given it to him.

Thousands of lives were to be sacrificed, rivers of blood were to be poured out, and the empire of the Children of the Sun was to pass away for ever like a golden dream ending in an awakening of horror because of that swift and irrevocable resolution of his. But all this was in the future. In the present were the glories of empire and the delights of Divine honours and unquestioned rule, and other than these he saw nothing.

The priest looked up as he felt his grip and saw his eyes, bloodshot and fierce, looking into his.

“Thou who wouldst have changed the course of Destiny appointed by the Divine Ones, who wouldst have robbed me of my rights, and made my Lord and thine a liar with his last breath—is there any need for me to tell thee the doom of the traitor and the worker of sacrilege? Thou and thy wife and thy children and thy children’s children shall share it, according to the justice of the Ancient Law. The fire shall consume thee and them, and the winds shall scatter thine ashes and theirs from the sight of men. The places where ye have dwelt, the works ye have done, and the fields ye have tilled shall be destroyed utterly and laid waste for ever, so that when men see the wilderness that was once thine home, they shall remember the law which says that the doer of evil and all that are his shall be taken away from among the Children of the Sun and no vestige of them suffered to remain.”3

The yet uncrowned Inca spoke these fearful words in a tone so coldly fierce that none who heard them doubted for an instant that he would use the power and the right that was his, and carry out the terrific penalty of the inexorable law to the last extremity, and none knew better how dire and all-embracing was the doom that impended over him and all that were his better than he who but an hour ago had held the highest and holiest dignity in the land, saving only that of the Inca-Royal himself.

Yet awful as it was, the old man gave no outward sign that it had any terrors for him. His eyes met the fierce gaze of Atahuallpa’s without flinching, and his voice, as he replied to his hideous words, was mild and yet unwavering—

“Son of him who was my Lord, there is no justice save that which the Divine Ones have given us, and there is no vengeance that is terrible save that which the sins of men call down from the hand of Him who may not be named. That which I sought to do was but to uphold the ancient laws and fulfil the parting spoken words of the Divine Manco, and the last words which my ears heard from the lips of my dead Lord and thine yonder told me that I had done rightly.

“Earth is small and life is short, but the Mansions of the Sun are vast and the life of those who reach them is without end. So I and mine are ready to depart. What thine eyes have seen here I know not, nor yet what it was that the eyes of him who is now among the Divine Ones last beheld, but ere long his lips will tell me——”

What else he might have said was never uttered, for Atahuallpa, with a cry like the snarl of a wounded mountain lion, shifted his grip from his shoulder to his throat and flung him stumbling backwards to the door, so that he fell prone across the threshold and lay stunned on the marble floor of the passage.

“Lift him up and take him away!” he said sharply to the frightened priests who were now huddled about the doorway. “He is no longer a Priest of the Sun or a man, but an outcast that may not be permitted to live. Let all of his blood be put in safe keeping instantly, and by the coming of our Father4 to-morrow let all be made ready for them to meet their doom. Your Lord has spoken.”

“Well and royally done, my son, and now my Lord!” said Zaïma the Queen, coming from where she stood by the head of the couch with both hands outstretched and making as though she would embrace him, but Atahuallpa started and shrank back ever so little. Yet he took her hands in his and bowed his head as if in deference before her, though it might have been that he feared to look into her eyes, and said humbly—

“The son of my father and my mother could have done no less. I did but what the Ancient Law has commanded. He has polluted the Blood with the poison of sin, and he must die. But go now, my mother, to your own house, for the embalmers must do their work before morning. Come, I will lead you to your door. Challcuchima, my uncle, come hither.”

As he turned to lead his mother from the room he stopped and beckoned to an old man, grey and bronzed and scarred with the marks of battle, but glittering from head to knee with plates of gold and silver linked together by rings and fastened on to a long tunic of fine, soft leather, clasped round the waist with a broad belt of interlaced gold and silver links from which hung a heavy golden-hilted sword of tempered copper. This was Challcuchima, the brother of the dead Inca, chief general of his armies, and the most renowned warrior in the Land of the Four Regions.

He had a short, copper-headed spear in his hand, and as he approached his new Lord he laid this across his shoulders, stooping slightly as one who bears a burden, for this was the act of homage which the greatest princes and nobles of the empire, even those of the Inca’s own blood, never dared to omit when they entered his presence, or were honoured by having speech with him, and as Atahuallpa saw it he smiled, and a sparkle came into his eyes, for it told him that the ally and the servant whose help was most precious of all to him had taken him for his lord and master.

“Let the room be cleared and guarded!” he said. “Remain here yourself with the guard and let none enter on any pretence till I return.”

“I hear but to obey, Lord!” the old warrior answered, bending yet lower. “I will guard the chamber with my life, even as I will guard thy dominions against all that shall dare seek to take them from thee.”

“Nor could they be better guarded than by him whose shield was ever the best bulwark of my father’s realm!” Atahuallpa replied almost tenderly, as he laid his hand lightly on the old man’s head. Then, leading his mother by the hand that had slain his father, he passed from the death-chamber through the little throng of princes and nobles, who bowed themselves almost to the floor as he went by and then arose and followed him at the bidding of Challcuchima, who at once blocked the passage with a guard of soldiers and remained alone in the room to await the coming of his master.

He drew the heavy curtains of brilliantly dyed wool, interthreaded with fine-drawn strings of gold, closely across the entrance and then he went to the bedside and reverently drew back the covering from the face of the dead Inca. He stooped and looked at it, and then suddenly started upright and clasped his hands over his forehead. Then he looked down again more closely than before, and, after gazing awhile, he closed with a gentle and reverent touch the glazed eyes that were staring up with their last look of horror scarce faded from them. Then he softly pushed the protruding tongue back into the mouth and bound up the fallen jaw with a strip of dyed cotton that lay beside the pillow.

“My Lord died hard, it would seem,” he muttered to himself, “and yet all thought his end could not fail to be peaceful. Well, well—hard or easy, it was very near, and I had rather have Atahuallpa the soldier-prince for my lord and leader than Huascar the lover of women and dreamer of dreams. What is done is past, and who knows but that some day we may have a wider realm than this and my Lord may reign with one foot planted on Quito and the other on Cuzco, master of all the Four Regions.

“There is no strife like the strife of brothers, and these two will not long reign side by side in peace. After that will come the day of brave men and stout warriors, and the victory shall be with us—with skill and order and strength and valour! It was a bold deed and a fearful one—I would have slain a score of men ere I had permitted it, yet now it is done and the Divine Ones themselves could not undo it.”

While Challcuchima was soliloquising thus to himself over the dreadful secret that he had discovered, a youth, who could scarce have seen his fifteenth year, was walking with slow steps and down-bent head from the great gate of the palace towards a vast building which loomed darkly through the dusk of the starlit night some five hundred paces along the side of the slope on which it stood, like the palace, facing on to the great square of the city.

Though he was one of those favoured Children of the Sun who ripened to maturity so rapidly, he had yet hardly passed from boyhood to youth, but his stature was already tall and his limbs lithe and strongly shaped, and his thoughts, as he walked, were rather those of a man than of a boy. He was one of those who had been summoned by the high priest to hear the last words of his father the Inca; for this was Manco-Capac, bearer of the Divine Name, and youngest and fairest son of Huayna-Capac and his sister-wife and Coya,5 Mama-Oello, princess of Cuzco.

What he had seen and heard in the death-chamber had filled him, not only with the darkest forebodings for his people and his country, but also with feelings close akin to agony and terror which in this hour were sharper and bitterer than they. The great building towards which he was walking was the House of the Virgins of the Sun, in which dwelt the fairest and most nobly-born daughters of the Sacred Race, awaiting the time of their marriage or vowed to their perpetual maiden-wifehood in the service of their Divine spouse, the Sun, and among them was one, the very gem and flower of them all, Nahua, the daughter of Amaro, son of Ullomaya the high priest, a little maiden who had seen but ten years of life, and whose beauty, like that of one of Nature’s fairest flowers just opening to smile at the sun, had in one fatal instant set his heart aflame.

He had seen her day after day during his sojourn in Quito, tending with her sister-virgins the flower-crowned altar of the Sun in the Great Temple. Their eyes had met and flashed to each other greetings in the language that needs no words to tell its tender and yet momentous secrets. After this his high rank and the favour of the Inca and Ullomaya had gained him the rare and priceless privilege of speech with her in the golden Garden of the Sun within the temple precincts.

The Inca and the high priest had seen their childish love without displeasure, and it might well have been that some day he would have taken her to his palace in the South on a green hill-slope that overlooked the splendours of Cuzco, and to his pleasure-house in the lovely paradise of Yucay—but now, how was he to think of such delight as this?

Could it really be possible that Atahuallpa, the son of his own father, had spoken those dreadful words, and that the light of to-morrow morning would show her to him being led out with her father and mother, her sisters and brothers, all that were near and dear to her, from the baby brother she was wont to fondle to the grandsire who was held to be the wisest man in the land, to be flung into the fierce flames that would consume them all till only their ashes were left, in obedience to the savage law which had been broken only in the vengeful imagination of the Inca—he had almost called him the Usurper!

As his eyes wandered over the long lines of mighty masonry which now formed, not her home but her prison, sorrow and anger seemed fighting for the possession of his soul, and dreams of rescue and vengeance, each one wilder than the other, crowded through his brain until he could bear the stress of them no longer. He felt that he must do something or go mad—and yet what could he do? He was powerless to alter ever so slightly the pitiless march of the inexorable law, even as he was to turn the vengeful Inca a hair’s-breadth from his course.

Even to intercede for the doomed ones who were now accursed would be sacrilege, and a word from Atahuallpa would send him to share their doom. As well might he seek to put forth his hand and take the brilliant Chasca6 from her place in the sky above the vanished sun as to save his child-love from her fate.

Yet he must do something, something that at least might set flowing through his veins the blood that seemed stagnating in his brain. The huge dark walls of the temples and palaces and store-houses and fortresses which filled this quarter of the city seemed to be coming together upon him, and the air of the streets seemed hot and stifling, but outside the gates was the free, open country, and above it the cool, wind-swept hillsides.

So, wrapping his cloak more closely about him and throwing one corner of it over his left shoulder, he set out to walk rapidly out of the square and along the street which skirted the wall of the House of the Virgins, and by this he reached one of the city gates. The guard turned out as he approached, but at the sight of the yellow fringe on his brow7 and the familiar features of the great Inca’s youngest born they fell back in an orderly rank and saluted him as he passed out.

Once clear of the city, he left the paved highway that ran for many leagues over the mountains until it joined the coast-road of the west, and with the long, swift tireless stride of his race struck out along a narrow path which led out of the valley, winding upwards towards the heights of Yavirá, which hid the dark peaks of Pichincha from the view of the city.

He had been striding along for nearly an hour when he saw a dark, slowly-moving shape on the path ahead of him. He quickened his pace, and as he came up with it it stopped and a familiar woman’s voice said to him—

“Have the tidings of evil to come reached the ears of the bearer of the Divine Name as well as those of the old woman? Art thou too, Prince, going to the altar of the Unknown round which the voices of To-morrow whisper?”

The voice and the strangely spoken words told him that she was Mama-Lupa, one of the oldest of the priestesses of the Sun and a palla, or wise woman, who was credited in the city with the gift of visions and prophecy. A swift thrill ran through his breast as he recognised her, for he knew that she could only have come from the House of the Virgins, where she dwelt, performing the work of her office and instructing the maidens in their daily duties and the simple lore which comprised their worldly education.

“My heart is hot and heavy, Mama-Lupa,” he said, “and my soul is full of sorrow. The city was hateful to me, and so I came out to breathe the fresh air of the mountains. Yet I scarce knew which path I had taken, though I could have taken no better one in such a time as this. Thou knowest the reason of my sorrow and how bitter it must be. Tell me, does my little Nahua know yet of her doom?”

“Nay, not yet, Prince,” the old woman answered, shaking her head; “neither she nor any other of the sacred maidens know anything of what has been done or said at the palace. So to-night she will sleep sweetly and dream of thee as ever.”

“Alas, Mama, those are cruel words though kindly spoken!” cried the young Inca, clasping his hands across his eyes. “She will dream of me, and to-morrow——”

“How knowest thou, Prince, what to-morrow will bring forth?” she interrupted in a sharp, shrill voice. “Let to-morrow look to the things of itself. Maybe it will have enough to do, and all those who shall see the evening of it. But, since thou art going my way and youth is stronger of limb than age, lend me the support of thy strong young arm and we will go together into the presence of the Unknown, and perchance I may be permitted to show thee signs of the things that are to be.”

So he gave her his arm to lean upon and together they went along the upward winding path, speaking but few words, for the old woman had but little breath to spare, and at last they stopped where the path ended before a great square altar of black stone which stood on the apex of the mountain.

Around them lay a scene which had not its equal even in the wonderland that was the cradle of their race—mountain piled on mountain and peak on peak, some dim and dark, and others gleaming pale and ghostly white beneath the clear light of the brilliant stars which thronged the heavens above, where the constellations of two hemispheres mingled, and before them towered the black peaks of Pichincha, dominated by the snowy central cone, some two leagues away to the north-west.

At one corner of the altar a stairway hewn in the solid stone led to the top, and, beginning at the foot of this, Mama-Lupa walked thrice around the base with her hands clasped behind her and her face upturned to the stars, muttering swift words which had no meaning for Manco save that he knew them to be spells and incantations of some mystic import. Then she stopped at the foot of the stairway and called to him, saying—

“Come and lead me to the top, Prince of the race that is doomed, for my eyes are dim to the things of outer sense though they see clearly with the sight that pierces the shadows that lie between now and to-morrow.”

Without speaking, he mounted the steps in front of her backwards, leading her by both hands until they stood together on the broad, flat top of the stone. Then she drew herself upright and, throwing her long, thick white hair behind her, she turned slowly round, facing all sides of the horizon in turns, and at the moment that she faced Pichincha for the second time a dull red glow began to flicker in the sky above it.

She grasped his hand and, stretching out her long, lean arm, pointed to it and said—

“Look, Prince and bearer of the Divine Name! My eyes are dim yet I can see it. Pichincha is putting on her fire-crown, and woe to the People of the Valley when it shall encircle her brows in all its flaming splendour! This night a deed of sin and horror has been done and the Divine Ones have seen it from the windows of the Mansions of the Sun, and they are angry. To-morrow a new reign will be begun with the torment and death of the innocent, if they in their anger do not stretch out their hands and do justice on the guilty. Nay, do not speak, Prince; thou hast come here to watch and not to speak.”

She ceased, still pointing towards the red glow in the sky, which, while she was speaking, had deepened and broadened; and now Manco, watching with straining eyes and bated breath, saw it broaden and deepen until he could see the jagged walls of the great crater standing out black and sharp against it, and above the ever-broadening glare perceived a long line of inky cloud like a pall of sable with a lining of flame.

Suddenly a dull roar of thunder seemed to roll up from the bowels of the earth and the cloud was rent in twain as though by a swift blast from the awakening monster’s throat. At the same instant a red-blue globe of fire rushed up out of the westward, sped across the sky, leaving a track of flame behind it, and then, in the mid-most heaven right over the city, it burst with a crash that shook the air and vanished.8

Manco, whose eyes, wide open and fixed with fear, had followed it in its awful course, covered his face with his hands and cowered shuddering at the old woman’s feet when the crash had passed; but soon another roll of thunder growled across the valley and he looked up to see what new horror was coming. The clouds above Pichincha were now leaping and tossing in billows of mingled flame and ink, and from behind the black crater walls shone the fierce red glare of the eternal fires, once more unchained after the imprisonment of centuries.

Then, as he watched, a thin tongue of flame, red as new-shed blood, crept out through a gap in the crater wall and began licking its way down through the crimson, gleaming snow on the mountain-side. At the same instant the thunder rolled out again deeper and louder than before, and he felt the great stone on which he crouched heave and reel beneath him.

As he sprang terror-stricken to his feet he saw Mama-Lupa stagger backwards, and he caught her in his arms to save her from falling from the altar. Again the stone reeled beneath them and he fell on his knees, dragging her down with him. But she freed herself instantly and, rising to her feet, she stood tall and menacing above him, pointing downwards towards the city, and cried in a shrill voice that rose almost to a scream—

“Go back, Manco-Capac, son of the race that is doomed, go back and tell them yonder that the Divine Ones are wrath with their children, and that in their anger they have unchained the demon powers which dwell beneath the mountains. Tell it in street and square, in palace and temple, that all may be ready, from the Inca on his couch of gold to the slave shivering in his hovel. Nay, have no fear for me, Prince, the Llapa9 will not strike me, for I have work to do to-morrow. I must stay here and watch and listen and learn the things thou canst not understand. Now go, go with thy best speed, that the warning may not come too late, for the Llapa travels fast and no man knows when it may strike.”

Scarcely knowing what he did, Manco obeyed, and stumbled blindly down the steps. When he reached the ground he paused, breathing deeply, and strove to steady his whirling senses, his hands clasped tight over his wildly beating heart. Then, with a last look at the great altar-stone crowned by the tall figure of Mama-Lupa with her fluttering garments and outstreaming hair sharply outlined against the red glare in the sky beyond, he turned and sped down the mountain-side towards the city as fast as his fear-winged feet could carry him.

When he reached the city the summits of the eastern mountains were already beginning to glow and glitter in the light of the still invisible dawn, but the angry glare which he had seen flaming so fiercely through the night had grown fainter and fainter until it had become so dim that the bulk of the Yavirá, rising up between it and the city, had completely hidden it from the view of those who had been in the streets and squares during the night.

As he entered the gate by which he had left he saw from the stolid calm of the guard who admitted him that no warning of the impending disaster had so far reached the men of Quito. The great city was just awakening from its slumber, for this morning every one would be abroad betimes. The news of the unheard-of crime of one whose holy office was believed to raise him above human frailty, and of the young Inca’s terrible sentence had reached every ear in the city overnight, and so every one woke early on the morning of doom.

Many, indeed, had not slept at all, for a crime so fearful as the high priest’s had been made out to be by the busy tongues of rumour was looked upon by the simple-minded folk as a presage of disaster, since, as they argued in their homely fashion, the Gods could not have permitted their chosen minister to sin if, for some cause or another, they were not grievously angry with their children.

More than this, too, vague, wild stories had ever and anon drifted up to the mountain-walled valley from the sea-borders of the West and North concerning the deeds of a strange new race of men, or demigods, as some called them, who had come from unknown lands, or perchance from the skies themselves, wafted by the winds in marvellous winged vehicles from which they could pour out thunder and flame and death—nay, it was even said that they carried the Llapa itself in their hands, and could smite with instant death all who offended or withstood them, while they themselves, mounted on mighty and terrible beasts which snorted fire and smoke from their nostrils, would fly over the earth with incredible speed. Moreover, they were made invulnerable to all weapons by clothing of white, shining stuff that neither spear nor arrow would pierce.

Some said that they were the long-foretold messengers from the Sun, fair of skin and mighty of arm, who were coming to rule over the Land of the Four Regions, and advance its borders till they included the whole habitable world and all the men that lived upon the earth. Others, again, said that they were demons which the powers of evil had let loose upon the world, armed with weapons of infernal origin, to lay it waste ere they repeopled it with their own hideous kind.

There had been strange signs in the sky, too, for flaming shapes had leapt across it, as one had done this very night, or sailed slowly through its depths, bright and terrible or pale and ghastly, like warning heralds of universal doom—and now the great Inca was dead, the grasp of the mighty conqueror was loosed from his sceptre, and his sword had been sheathed, and the first act of the new Inca had been the uttering of a sentence which doomed the noblest and holiest family in the land save his own to utter extinction and a death of torment. It was little wonder, then, that sleep had fled from many eyes in Quito that night.

When Manco reached the terrace in front of the palace he saw men already dragging and carrying beams and planks and fagots towards the centre of the square, and his heart, beating hard with the exertion of his long and swift journey, stood still in an instant, as he remembered the awful purpose to which they were destined; for the labourers were about to build the funeral pyre on which his beloved Nahua and all her dear ones were to perish amidst the torment of the flames ere the new-born day was but a few hours older—unless, indeed, some mightier power than that of the despot who had doomed them should be exerted to save them, and, if not to save them, perchance to avenge them.

Scarce knowing what he said or did, he went to the guards at the great door of the palace and sought to find admission, but all he gained was the reply, respectful and yet inexorable, that none, not even a prince of the Blood, could now enter the palace until the Inca came forth to salute the coming of his Father, the Sun. It was in vain that he commanded and besought by turns, and spoke of the anger of the Gods, and coming disaster to the city and its people. Only the formal words of blind obedience to orders answered him, and when at last he sought to force his way to the door crossed spear-shafts and lowered points showed him that he must die before he reached it.

Then at length he drew back, and in the tumult and bitter agony of his soul he paced up and down the broad terrace muttering disjointed and incoherent words, and watching with dry, aching eyes the stolid labourers silently doing their work in the square.

Beam by beam and plank by plank he saw the great scaffold rise, like the creation of some hideous magic, by the toil of many hands, and all the while the eastern peaks glowed brighter and brighter, heralding the coming of the fatal hour.

At last the guards fell back from the door of the palace and stood to their arms. A weird, low sound of song seemed to rise from all parts of the city at once, every moment growing louder and stronger and more jubilant. Then, as though called into being by some spell or miracle, troop after troop of gaily-accoutred soldiery, glittering with gold and silver and burnished copper, and clad in bright-hued uniforms, streamed out of the streets into the square and formed up in silent, orderly ranks along its sides and on the great terrace which flanked it.

Then from the Temple of the Sun and the House of the Virgins came two long processions, one of priests and the other of the Brides of the Sun, chanting the Hymn of Greeting, for this was no ordinary day; it was the morning on which the new Inca was to hail the coming of his Father and his God for the first time, and, standing in the radiance of the first beams that fell into the valley, place the imperial borla upon his brow.

The priests and virgins, entering the square from opposite sides, took their places at either end of the great terrace on which the palace stood, leaving a triangular open space narrowing towards the great doorway and opening to the eastward. Manco went and stood among the guards by the door, eagerly and yet hopelessly scanning the shining ranks of the virgins in the vain search for the face that he would willingly have given his life to see among them, and so he waited till the master of human fate throughout the valley should come forth, and the solemn ceremony which it would be death to interrupt even by a word or a gesture should be over.

And as he waited and watched the silver deepening into gold and the gold blushing into crimson behind the far-off peaks, he thought of the fiery pall that he had seen flaming above Pichincha through the darkness of the night, and in his fancy he saw it rise and spread with the blackness of the cloud and the glare of the flame till it blotted out the dawn and hung like a pall of death and desolation over the whole of the lovely valley.

Then a louder burst of song roused him from his waking dream, and he turned to the door and saw Atahuallpa, splendid in the pride of his imperial array, shining with gold and glittering with gems, come forth with a slow, stately step, his head bare and down-bent, like one going into the presence of his God, and carrying in his hands the scarlet Llautu fringed with the scarlet and gold borla, the insignia of his sovereignty and the symbol of his Divine descent.

He came out alone and walked into the midst of the vacant space. Then behind him came the High Priest of the Sun, newly appointed in Ullomaya’s place, with the chief priests attending on him. Then came Zaïma the Queen-Mother with the princesses of her household, and then Challcuchima with his brother chieftain, Quiz-Quiz, and a glittering array of the chief warriors of the realm and princes of the Sacred Blood.

As they halted each at their proper distance behind the Inca the melody of the singing suddenly stopped, a brilliant point of fire blazed for an instant beside the peak of Antisana, then the whole summit of the great mountain seemed to melt away into a sea of flame, and at the same instant every knee, from that of the Inca to that of the meanest labourer in the city, was bent to the earth in adoration.

Then in the midst of the solemn silence of the breathless multitude, Atahuallpa upturned his face towards the risen sun, and in a loud, clear, musical voice, whose words rang like the notes of a silver trumpet through the silent, crowded square, spoke for the first time the solemn Invocation to the visible shape of his Father and his God.