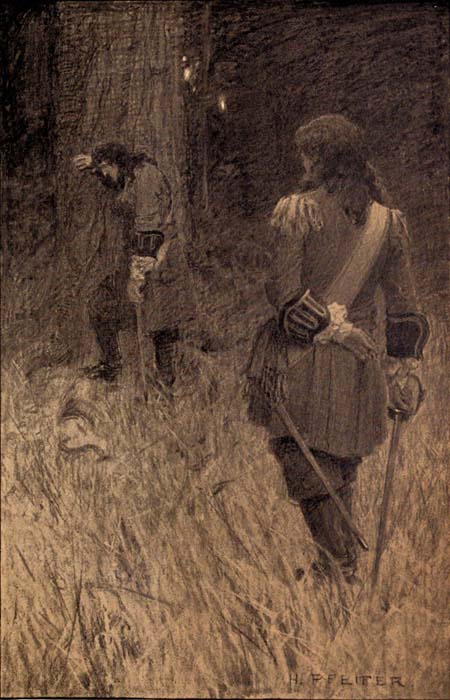

“‘I give the lives of these gentlemen to you. Your secret is your own’”

[p. 180]

MY LADY OF

CLEEVE

BY

PERCY J. HARTLEY

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

HARRISON FISHER

AND

HERMAN PFEIFER

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD & COMPANY

1908

Copyright, 1908

By DODD, MEAD & COMPANY

Published, January, 1908

| Chapter | I | Of How We Came to Cleeve | 1 |

| Chapter | II | Of the Light that Shone in the Fog | 17 |

| Chapter | III | Of the King’s Errand and of My Lady’s Welcome | 34 |

| Chapter | IV | Of My Lady’s Mission to Exeter | 55 |

| Chapter | V | Of How Three Gentlemen of Devon Drank the King’s Health | 77 |

| Chapter | VI | Of How I Played Knight-Errant and of My Lady’s Gratitude | 97 |

| Chapter | VII | Of Certain Passages in the Rose Garden | 117 |

| Chapter | VIII | Of the Duel in the Wood | 136 |

| Chapter | IX | Of How My Lady Played Delilah | 156 |

| Chapter | X | Of How My Lady Played Delilah—(continued) | 176 |

| Chapter | XI | Of What Befell on the Terrace | 193 |

| Chapter | XII | Of the Gentleman Aboard the Good Ship “Pride of Devon” | 209 |

| Chapter | XIII | Of the Lonely Hut on the Shore | 230[vi] |

| Chapter | XIV | Of the Homecoming of His Grace of Cleeve | 248 |

| Chapter | XV | Of the Coming of the Dutch Dragoons | 269 |

| Chapter | XVI | Of How I Repaid the Debt I Owed My Lady | 288 |

| “‘I give the lives of these gentlemen to you. Your secret is your own’” (p. 180) | Frontispiece |

| “Descending the steps, she stood facing me not ten paces distant” | facing 40 |

| “‘You!’ my lady gasped in a choking voice” | “ 90 |

| “He leaned against its knotted trunk, while the blood dripped steadily upon the grass” | “ 146 |

| “A very brief examination sufficed to assure me that the fellow was but stunned” | “ 224 |

| “On the threshold stood the Earl of Cleeve himself” | “ 262 |

MY LADY OF CLEEVE

“Yonder is Cleeve!” said the sergeant.

I held up my hand and the troopers halted. The rain, which had been falling steadily since noon, had now ceased; and a watery gleam of sunshine bursting from the sullen stormclouds overhead lighted up the crest of the hill upon which we stood, and the well-wooded Cleeve valley below us, than which there is none more beautiful in all Devonshire. Behind us lay the barren surface of the torrs—mile upon mile of rock-strewn, wind-swept summits—thrusting their gaunt and rugged outlines high into the air in spurs as varied as they were fantastical. But at our feet the ground fell sharply away, covered with a wealth of golden gorse and bracken and scattered clumps of timber that grew ever thicker toward the bottom of the valley; yielding nevertheless the glimpse of a white road which wound its way serpentlike down the centre.

Here and there also the glitter of water showed through the trees, where some streamlet kissed by the sun’s rays shone with the radiance of burnished silver. From thence the woods rose in one dense mass upon the opposite[2] slope, until they broke at length upon the very edge of the rocky cliffs that guard this portion of the coast, and beyond these again were the dark green waters of the Channel.

It was a scene that at any other time would have compelled my ardent admiration. The fertile valley nestling at our feet, clothed with its rich carpet of oaks and beeches, and rendered doubly welcome by contrast with the bleak, treeless surface of the torrs through which we had toiled since daybreak. But befouled with mud, wet and weary, we were in no condition to mark its beauties or to appreciate them. Moreover, though it was yet early June, a cold wind was rising, rustling in the treetops below us and bringing with it the odour of the sea.

As we sat there upon the brow of the hill, the steam from our jaded horses rising around us, we shivered in our saddles. For the last two hours, save for a muttered oath from one or other of the troopers when their weary animals stumbled, we had ridden for the most part in silence. Even Graham—gayest and most debonnaire of cornets—had scarce opened his lips save to answer some remark in monosyllables. And that fact alone was more significant than words to prove to what a state of depression the lonely torrs and the falling rain had reduced us. He had fallen somewhat behind with De Brito, but they spurred forward now upon seeing me halt. I had, I confess, no great liking for Cornet Brito; though to give him his due, had he paid less attention to the wine bottle he had the making of a good sword. But his was a[3] coarse, brutal nature—sullen, revengeful, and without restraint—alien alike in every respect to my own. For I hold that a man may be forced to live by the wits that Nature has provided him with—he may be forced to sell his sword and service to the highest bidder—but he need not forget, thank God, that he was born a gentleman.

As for Cornet Graham, he was a merry, careless-hearted boy in appearance, with an eye for every comely maid, and a mind, one would have thought, running only upon the sit of his peruke or the latest fashion in sword knots. Yet his slight figure and fair boyish face belied his nature, which was as keen and ruthless as any of the troopers plodding at our heels. Even now I noted at a glance that though he was as wet through as the rest of us, no mud splash soiled his clothes. And his white cravat limp though it was, was yet tied in a fashion that would have done credit to the Mall or St. James’s. Indeed, to him London was the world.

“A curse on these endless hills!” said De Brito sullenly, as they drew rein at my side. “Why do we halt?”

For answer I pointed to where some three miles to our right, on the opposite side of the valley, and perched apparently upon the very edge of the cliff, the grey stone chimneys of a house rose above the surrounding trees. Beyond this the mighty head of Cleevesborough reared itself into the sky. And at its foot, marked by the smoke which hung, motionless, in the heavy air above it, lay the little port of Cleeve, to which it gives its name.

“Yonder is our goal!” I said curtly.

[4]’Twas a sight to see the way in which his dark face brightened at the prospect.

“Then push on, in the devil’s name!” he cried querulously. “There is an inn at Cleeve?”

“I do not know,” I answered shortly, my mind running at the time upon far other matters.

“Who talks of inns at such a moment?—though an inn there is, and a good one!” said Cornet Graham. “But there is a woman yonder,—to see whose face is worth twenty such wettings.”

“Perdition take the woman!” growled De Brito in reply. “Give me a roaring fire and a cup of sack to keep out this cursed wet! Burn me! Women are as plentiful as blackberries; aye, and as cheap for the plucking.”

“But not such as this one!” cried the younger man with some heat. “’Tis five years ago, I swear, since I saw her first in London. But she was accounted then the toast of the Court by those most competent to judge in such matters; aye, even by King Charles himself—may the devil rest his soul! He deserved well of his people, seeing that he did his best to be a father to them.”

“So that, but for the accident of his death, we might have had a second Castlemaine,” I put in sneeringly. The mention of this woman, about whom the cornet had raved unceasingly since he had learned our destination, jarred upon my ears. He shook his head in dubious fashion.

“You do not know her,” he answered reflectively.[5] “Proud as Lucifer, she is no woman to play the wanton, even to a king! Cold as proud, she is——”

“Pshaw, man! For shame! ’Tis my belief you think more of this paragon of virtue’s face than of the business that we have in hand.”

“Why not?” he cried quickly. “’Fore gad! Spies and Papists are common enough at present, but there is only one Lady Lettice Ingram, and—why, curse it, Cassilis, she is one of the loveliest women in England—the favourite toast of every tavern in town!”

“Such is fame!” I remarked caustically, and fell to scanning the house again. And I confess that the longer I gazed, the more difficult appeared my task.

For these were stirring times, and it behooved every man to keep a still tongue and a ready blade. All England was divided into two factions. The one still clinging to the restoration of the Stuart in the person of James II, the other content to follow the fortunes of Dutch William. Moreover, in every shire throughout the country were the spies and agents of the French king, working in secret to foment a rising among the Catholics. For Louis XIV. must have a finger in every European pie.

It was to arrest one of these agents—no less a person than the Marquis de Launay—that I had been sent hastily from Exeter, information coming to the authorities that he was in hiding at Cleeve Manor, an old Tudor mansion on the coast of Torbay belonging to the Ingram family, who were staunch upholders of the old religion,[6] and the head of whom it was whispered was already with King James in Ireland, and high in his favour.

As I sat now, pondering upon the best way to carry out my orders, I saw at a glance that, standing as it did upon the edge of the cliff, to ride up to the front of the manor would be to render it an easy task for our quarry to escape by sea. Clearly, by some means we must gain the beach, in order to cut off any such method of escape from the rear. Accordingly, I told off the sergeant and a dozen men for this duty, with whom I purposed going myself, bidding the two cornets to lie hidden with the remainder of the troop until dark, and to then follow the road leading to the manor. Arrived there, Cornet Graham was to surround the front of the house, but to await an agreed signal between us ere he attempted to force an entrance. Meanwhile, De Brito and twenty troopers would ride on and overawe the village, a task which I knew would be both welcome and congenial to his temperament; nor was I wrong in so thinking. As I made an end of my instructions, he drew his thick and grizzled brows together in a sullen scowl that boded mischief.

“You need fear no trouble from that quarter,” he said grimly. “I know my work too well.”

“Aye, but none of your devil’s tricks here!” I retorted sharply. “We are not in Tangiers!”

For a moment his swarthy face wore an ugly look and his fingers sought his hilt. But he thought better of it.

“Leave me to do my own business in my own way!” he muttered sullenly. “Give me the village and the[7] tavern—and slit me if I interfere with you in the matter of the dainty doves yonder!” And he nodded in the direction of the house.

His tone was one of such studied insolence that at any other time I should have called him to account. As it was, I shrugged my shoulders contemptuously and turned to Cornet Graham. On my life, he had pulled a little comb from his pocket and with this he was endeavouring to smooth his matted periwig.

“Remember,” I said warningly, “M. de Launay is to be taken alive.”

“If he is there at all,” he answered, “and this does not prove a fool’s errand!”

“It is like enough to be that,” I said carelessly, “since it is a king’s. But be consoled. At least, you will see this Venus!”

He cried out something at that, but I did not stay to hear. I gathered up my reins and, with a wave of the hand, rode after the troopers.

They had halted at the edge of the road awaiting my orders, and I saw that the sergeant had made a careful selection for the arduous work they had before them. As they sat there in their saddles, their fierce, swarthy faces bronzed to a coppery hue by the scorching suns of Tangiers, their coats, once red—worn and faded to a mottled purple, they were as ill-favoured a set of rogues as one could meet, not even excepting Kirk’s Lambs. I placed myself at their head, therefore, and leaving the road behind us, we plunged at once into the woods. So dense were these that ere we had proceeded more than[8] a quarter of a mile I was compelled to dismount the men and to send back our horses in charge of two of their number. With the remaining troopers at my heels, I essayed to make the ascent on foot. Nor was it an easy task even then. From every branch the raindrops dripped upon us, so that, wet before, we were doubly so ere we had advanced but a short distance. Tripping over roots, torn by brambles, a dozen times we came down upon our faces, rendering us in a truly pitiable condition when at length we reached the summit. Nor did luck befriend us even then.

In front of us and on either side the woods spread to the edge of the cliff, the latter falling sheer away to give us a sight of the white-capped rollers, over which the gulls were wheeling, three hundred feet below, and with no sign of a path by which we might gain the shore. We separated now, making our way right and left as fast as the thick growth and the slippery nature of the ground would permit, while in my heart I cursed the delay, for the light was fading fast. It was not long before a shout from one of the troopers proclaimed that he had stumbled upon that which we sought. I made my way to his side as quickly as possible, and found him standing on the brink of a little combe, a mere cleft in the hillside, its sides thickly wooded, and with a swift stream, swollen by the rains from the torrs above, flowing in a succession of white-lipped falls down its centre. It was not an inviting road to take, and I would willingly have sought for a more open spot, but we had already lost more time than we could well spare, and dusk had[9] fallen on the silent woods. Moreover, the heavy grey clouds, drifting low from the direction of the sea, momentarily grew darker and more threatening, giving promise of further rain. I rallied the troopers, therefore, at the head of the combe, and with the sergeant at my heels, plunged into the glen.

At first the ground was fairly open, and we were enabled to make good progress through the thickets of alders and rushes that fringed the banks of the stream, but ever as we advanced the green walls of the glen grew steeper and narrower, until we were forced to take to the stream itself, making our way from stone to stone that lay mossgrown and prostrate in its bed, or at times wading ankle deep through some shallow pool. It was as if we were cut off from the world. A damp, earthy smell, begotten of the winter’s leaves’ decay, filled the air. There was no sound save the song of the water swirling at our feet as it brawled amongst the pebbles and chafed in its narrow course, the occasional fall of a branch upon the hillside above, and in the distance the ever-increasing murmur of the sea.

For over half a mile we proceeded thus, so that it was with no little satisfaction that at length we saw the light, such as it was, gradually strengthening in front of us. Now the trees grew thinner, admitting a breath of sea air, which stole through their twisted trunks and fanned our faces. As we continued to advance, the glen as suddenly receded, and a moment or two later we came out upon the beach.

We found ourselves in a little shingle-covered bay, the[10] extremities of which were shut in by the rocks, giving us no sight of what lay beyond. Above our heads on either side towered a mighty wall of rock, its grey, rugged surface broken here and there by patches of withered grass. And here the sergeant, who was a few paces in front of me, suddenly stopped.

He was a grizzled, battle-scarred veteran of the wars of Flanders, with whom I had once made a campaign upon the Rhine, and to whom for that reason I allowed some freedom. His looks, ill-favoured enough at best, were in no way improved by the scar of an old sword cut gained in some wild foray against the Turk, which scar, starting from his right eyebrow, stretched crosswise to his chin; twisting both nose and lips to their utter detriment and imparting a peculiarly forbidding and saturnine expression to his face.

“What is it?” I said sharply. “Why do you halt, man? The tide is out, and the light will serve.”

“Aye,” he answered slowly, “the tide is out, but——”

“But what?” I cried impatiently. “Come, out with it if you have anything to say!”

“Well, I like not that!” he rejoined with some hesitation, pointing out to sea.

Following the direction of his outstretched arm, away over the surface of the water, some two miles distant, but creeping each minute slowly and insidiously nearer, stretched a white wall of vapour, beneath which gleamed the foam-crested summits of the waves.

“Well?” I said contemptuously. “What of it? Have[11] you never seen a sea fog before, or are you afraid?” I continued with a sneer.

“Neither of man nor devil!” he retorted with some heat. And to do him justice, I knew that he spoke truth. “But this—this is different. To be caught against that”—he nodded toward the cliff—“and to be drowned like rats!”

I saw that his words were not without effect. The troopers, already wearied by the day’s exertions, glanced askance at one another and began to mutter. At all hazards this must be stopped, and at once. I faced round on them.

“Who talks of drowning?” I cried angrily. “Curse you for a fool, man! ’Tis but a mile to go at most. But if you fear to venture, sergeant,” I continued, “you can return the way we came. And stay, I will send a couple of men back with you to bear you company; you will find it dark in the glen!”

He saluted at that, a flush of shame upon his face.

“Very well,” he said slowly; “let it be forward then. Only—I have warned you.”

“And you others!” I continued in a fierce tone, turning upon them and letting my hand fall lightly upon the butt of the pistol in my sash. “Have you anything to say, or do you forget who I am, you knaves? I will find a quicker death than yonder waves for the first man among you who questions my orders!”

I looked them squarely in the face, and their muttering died away. Steeped as they were in crime and license, I was their master, and they knew it. For a moment or[12] two longer I remained silent to give full effect to my words, but not a man spoke.

“Forward then!” I said shortly; and we set off along the beach.

Not that their fears were altogether without foundation. The intense loneliness of the spot, increased as it was by the gathering dusk, was sufficient to daunt the stoutest heart. The wind was rising, moaning in the cavernous hollows and crevices of the cliff, from which came ever and anon the weird cry of some sea fowl, circling round its nest in the rocky wall above. And save for this there was no other sound but the hoarse murmur of the swift, incoming tide.

Rounding the rocks which screened the bay, we found ourselves in a second one, a complete replica of the first. And beyond us, headland upon headland, serrated against the darkening sky, stretched faint and shadowy into the far distance.

Our progress was slow, for the beach was composed of small, slate-coloured pebbles, flattened and rounded by the wash of endless surges, and into which our heavy military boots sank deep at every step. Here and there we were forced to skirt some mass of lichen-covered rocks; which, torn from the cliff side, lay scattered upon the shore at its base, their sharp, needle-like summits wreathed with tangled seaweed and their caves and hollows filled with the flotsam of the tides.

And now the fog rolled down upon us, at first in thin wreaths of vapour that floated in ghost-like silence like the first sentinels of an advancing army, but growing[13] ever thicker and thicker as they approached landwards, until they wrapped us completely round in their damp embrace, blotting out everything from our vision save the wall of cliff upon our right, which loomed dark and menacing through the mist. The wind rose as suddenly to a gale, sending the fog wreaths eddying around us, and bringing with it a cold rain that at every successive gust beat in our faces, blinding and confusing us. A hundred times I cursed my folly and recalled the sergeant’s warning. He was at my elbow now, at times his figure appearing distorted and giant-like as the fog thinned somewhat; anon banishing altogether from my vision, swallowed up by the mist.

How long we struggled on thus, buffeted by the wind and rain, falling over the jutting rocks, I do not know; but it was in a lull in the gale, when the wind died down for a moment and the fog lifted, that I felt myself seized by the arm and plucked violently backward. It was none too soon. From out of the mist ahead appeared a green wall of water capped with foam. Down it thundered, breaking upon the pebbles at my feet, sending the salt spume flying above my head and swirling round my knees in a cataract of foam.

Even then, so sudden was the surprise, that the backwash was like to have swept me from my feet; but the sergeant’s grip tightened upon my arm and dragged me back to safety. And in a moment I realised what had happened. We had reached the end of the bay, into which the sea had already entered. I put my lips to the sergeant’s ear.

[14]“Back to the cliff,” I shouted, “and climb, man! Climb, or——”

There was no need to finish the sentence. Not a man there but knew our danger. We began to retrace our steps. It had grown so dark now that it was only when the curtain of fog parted to a more violent gust than usual that I was enabled to distinguish the form of the trooper upon my right. The rain which we had experienced all day was as nothing to that which fell upon us now. It descended in sheets, drenching us to the skin and numbing us with its icy cold. For a while, indeed, a species of coma seized me. I thought of the cornets waiting in the roadway above, and wondered idly whether they would succeed in achieving the arrest of the man we had come so far to seek, and whether, by chance, upon the morrow they would find some relic of our party floating in the wash of the tide to tell the story of our fate, for I did not deceive myself. To climb the cliff even in the daylight would have been a hard enough feat; to do so at night, in the darkness and fog, was an impossibility. And though I was willing enough for the troopers’ sake to make the attempt—aye, and to encourage the effort—yet in my heart I knew that there could be but one ending.

It seemed hard, I remember thinking dully, that a man who had passed unscathed through the perils of many battlefields—hard for a man who had made a campaign with Montecuccoli, and whose arms had held the great Turenne as he fell from his horse, struck down by a cannon-ball upon the banks of the Rhine—to be drowned[15] at the last in a little bay upon the lonely Devon coast. I was aroused from these reflections by the sound of an oath and a heavy fall, as the trooper upon my left stumbled over a black mass which loomed up suddenly in his path. He was on his feet again ere I could reach his side, and gave vent to such a ringing shout that it pierced above the gale and brought us all around him. That which he had fallen over, very providentially as it proved for us, was a boat anchored to the beach by a short length of rope fastened to a stone. With renewed hope we scattered again in search of the path which the inmates of the manor must have been in the habit of using when passing to and fro to this small craft. At length an idea struck me, and raising my hand to pass it carefully over the rocky wall above me at a little above the level of my shoulder, I came upon a ledge. By climbing upon the sergeant’s bent back, I was enabled to draw myself up to it at the cost of a few bruises, and to clamber upon its flat surface.

It was, as near as I could judge, some ten feet square, and in the far corner my hands came in contact with a flight of steps leading upwards, roughly hewn in the cliff side. Five minutes later the whole party of us stood upon a little platform, side by side. And then, drawing a long breath, I essayed to make the ascent.

There were eighteen steps in all, giving place to a path, a mere narrow ledge on the surface of the cliff, at no place more than four feet wide, and with a sheer drop upon the one side to the beach below. Along this we crept, at every fresh gust of wind flattening ourselves[16] against the rocky wall upon the right and clinging to its jagged fissures. It was a weird experience, I vow, to be suspended thus ’twixt sea and sky; no sound save the whistling of the wind in the crannies of the cliff, the roar of the pitiless surges below us, or the harsh scream of a gull from the mist out at sea. Yet I have travelled this same path since by daylight, and I have often thought that the thickness of the fog upon that night was most fortunate for us, sparing us, as it did, the full knowledge of the yawning which lay at our side, the sight of which might well have turned the strongest head giddy. Even as it was, at a place where the ledge took a sharp turning, a sudden blast struck me with such violence that, taken off my guard, for a moment I was in danger of being torn from my foothold, and only by driving my nails into a crack of the rock until the fingers themselves were left all raw and bleeding was I enabled to withstand its boisterous pressure.

The breeze passed. And taking courage of my experience, I made haste to round the dangerous corner, shouting back a word of warning to the file of men creeping at my heels. Even as we ascended the noise of the waves grew fainter, until, after travelling some twenty minutes thus, a new sound was added to the patter of the rain upon the side of the cliff—namely, the howl of the wind in the treetops above us.

A last effort as the way grew steeper yet, and I gained the summit, to fling myself panting and exhausted upon the turf in the thick darkness beyond.

It must have been for the space of full five minutes that I lay thus, with quivering nerves and labouring breath, upon the sodden ground, with the raindrops beating down upon me, ere I roused myself sufficiently to get to my feet and call to the sergeant. His voice answered me from out of the night, somewhere at my side. I bade him ascertain that none of the party had got separated in the darkness. Accordingly, he called the troopers one by one, and at each name an invisible speaker answered: “Here!”

“They are all present!” said the sergeant gruffly, who, though distant from me but some three feet or so, showed only as a darker patch upon the murk beyond. It was the very gloom of Egypt that encompassed us. Therefore, I gave instructions that each trooper should lay hold of the belt of the man in front of him, and setting our faces away from the direction of the sea, we moved slowly through the inky blackness that surrounded us. That there were trees around us I had ample proof, not only by the sound of the wind whistling in their branches overhead, but also by the fact that ere we had advanced a dozen yards I tripped over a projecting root, my head coming into such violent contact with an unseen tree, that I was glad to lean for a moment or two, sick and[18] dizzy, against its knotted trunk. Thereafter I was more careful, feeling my way from tree to tree, and probing the darkness in front with my sheathed sword.

We had been moving a long time thus, or so it seemed, when the trees on either side abruptly ceased, and turn it which way I would, my sword encountered only empty air. Across this open space we slowly moved till at the thirty-seventh step as I counted my sword struck with a sharp tinkle against what I took for the moment to be a stone wall. It was not until I had passed my hand over its flat surface and down its base that I discovered the nature of the object upon which we had stumbled. It was the sun-dial, such as I had often seen in France, and I knew by its shape that I was not mistaken. From this I argued we were somewhere within the gardens belonging to the house, and here the man who was behind me (it was the sergeant) loosened his hold, and I felt him groping upon the ground at my feet. Presently he rose, as I could tell by the sound of his voice.

“There is a path here,” he said; “I can feel its border. Aye, and a broad one.”

“In that case,” I answered, “lead on! The house cannot be far away.”

I resigned my place to him, therefore, at the head, and with frequent stoppages we made our way slowly along the path. A dozen times at least we strayed from the track, and it was only with the greatest patience that we were enabled to retrace our steps. We must have travelled thus for some five or six hundred yards, when we almost ran into a stone wall, that lay on the right-hand[19] side of the path, and saw before us a dark mass looming through the mist. We felt our way by the side of this wall until, upon turning sharply round the corner, the sergeant’s hand was laid upon my arm, and we came to a sudden halt. For there, not twenty feet distant, from an open doorway, a bright light was streaming out into the fog.

For the moment we were sheltered somewhat from the wind by the building itself, and I thought that in between the gusts I could distinguish the sound of voices. Though this was the very thing we had expected to encounter, yet so long had our eyes been accustomed to the darkness, that it came even now as somewhat of a surprise to us and we stood staring stupidly before us. Moreover, the light from whatever source it came did not burn steadily, but every now and then it was partially obscured, as if some one or something came between it and the doorway, to burst forth a moment later with renewed brilliance, flinging its yellow aureole of light upon the fog, and serving but to increase the impenetrable shadow that lay beyond. I came to myself with a start and slowly unsheathed my sword; and I heard a faint tinkle of steel go rippling into the darkness behind me as the troopers did the same. Then, with the sergeant at my side, I stole quietly forward, and halting at the edge of the circle of light, ourselves unseen in the shadow, we peered into the room.

At first I could see nothing, but as my eyes grew accustomed to the brightness within, I was enabled to make out the interior. It was a stable, and by the light[20] of a couple of lanterns hung upon the wall an old man was whisping the mud stains from a magnificent chestnut mare, pausing every now and again to rub her sleek, glossy sides. A younger man muffled in a cloak was standing with his back to us, a lantern at his feet.

My eyes were rivetted upon the mare, for I have ever been a lover of horses, and indeed to a man who has spent the better part of twenty years in the saddle and who has owed his life again and again to the speed of the animal beneath him, the love of them becomes as it were a second nature. I saw that this was an animal rarely met with in a thousand and that it carried a lady’s saddle and bore the signs of recent hard riding.

I started when the sergeant touched my arm and pointed to the younger man’s belt. Following the direction of his outstretched hand, I saw that this man’s cloak had fallen open and that he carried a bunch of keys at his side. By this I judged him, and rightly so, as it proved, to be the steward. This was a stroke of unexpected good fortune, for the means of gaining access to the house now lay to our hands.

It was this latter who was speaking, every word coming plainly to our ears through the open door.

“Hast nearly finished?” he said impatiently.

“Finished?” said the other, in a high-pitched, querulous voice, and I saw he raised his head and disclosed a yellow face seamed with a hundred wrinkles, that he was much older than I had first thought, and with the unmistakable look of a man who has spent his life amongst horses. “How should I be finished—and look at Carola![21] Been down on her knees, she has! But what does my lady care? She can stop in the light and warmth yonder. ’Tis old Reuben must clean her horse. Let old Reuben go out in the wet and fog. Nobody minds what happens to him!” He broke off in a fit of coughing.

“How now, old grumbler!” said the other sharply. “That is a lie, and you know it! Aye, and if my lady heard you she would make you smart for those words!”

The old man looked up with a grin that disclosed the few yellow stumps remaining in his head. “She would that, lad!” he chuckled. The steward nodded gravely.

“You will find that my lady does not forget a service,” he said slowly.

“God bless her!” said the old man softly, stooping once more to his work.

“Amen to that,” the steward answered.

So that for the first time my curiosity was aroused as to what manner of woman this could be of whom they spoke in such terms.

“Aye, it will be a bad day for us all if she should marry this Frenchman,” he continued, shaking his head.

“The devil take all Frenchmen!” the old man burst out in his thin, quavering voice, and with true insular prejudice. “She will wed a man—a man, I tell thee—not a tricked-out, scented popinjay. Frenchman indeed,” he continued with fine contempt. “Mark my words, lad! Eight and sixty year I’ve lived here, boy and man, and I’ve never seen a Frenchman yet that was a man! It’s not in ’em, lad! It’s not born in ’em!”

[22]“I misdoubt you have seen one at all before, old Reuben!” answered the other, but the old man only continued to nod and mutter to himself. “But every one to their taste,” the steward added. “My lady will make a good match, and a good wife.”

“Aye,” the man Reuben answered, “when she is tamed, lad; when she is tamed—and Lord help the tamer!” he added with a chuckle that trailed off into a fit of coughing. The steward waited until he had recovered his breath, then:

“There be some at the house yonder who think ’tis Mistress Grace he would be wedding,” he said slowly, but the old man only shook his head.

“It’s not my lady,” he answered doggedly. “I’ll take my oath of that! No, nor Mistress Grace either.”

“Then why is he here?” cried the steward eagerly. “Tell me that!” The other raised his head with a cunning look on his wrinkled face.

“I have heard it said that James Stuart is in Ireland,” he said slowly.

“Bah!” the man in the cloak answered. “Every one knows that!”

“Hark to that now!” the old man replied, apostrophising the mare, that by way of answer whinnied softly and laid her head upon his shoulder. “Every one knows that! Every one knows——” He broke off with a half inaudible chuckle.

“Well, ’tis true, is it not, old dotard?” said the other sharply.

“How should I know?” answered the old man querulously.[23] “Reuben the dotard! Reuben the fool!” and again he laughed mirthlessly.

“Mark you,” said the steward quickly, “I love not Dutch William. I am for the Stuarts, I! But this I say, that James is no fighter, and if he should give battle to William—pho!” And he snapped his fingers expressively.

“Aye, if he should!” the other replied significantly. “But—” and he sank his voice slightly—“what if he were to slip away and leave this Dutch hog in Ireland! What if he were to land here?”

“Here?” the steward cried in a startled tone.

“Here!” the old man went on triumphantly, “and the Earl with him! Why, at the master’s call we’d have the whole countryside in arms!”

“Aye, but what has the Frenchman to do with it?” the other cried in a tone of bewilderment.

“Nay, how should I know!” he replied, grinning. “Reuben the dotard! Only, did ever a Stuart have money!” he added softly, with a glance of contempt at the man before him.

A light seemed to break upon the steward. “Ha, I see!” he cried excitedly. “Then you think——”

“I think that the mare is listening,” said the old man with a sour smile, and he stooped to continue his task. Nor for all the steward’s entreaties would he again open his mouth. He gave up the attempt at length.

“Well,” he said reluctantly, “I may not bide here longer. Do you make haste, and we will talk of this again.” He stooped and raised the lantern from the[24] floor, and with this swaying in his hand he came toward the open doorway to walk into our arms.

When the sergeant had clapped a pistol to his head there was no more surprised a man in all England. He could not be expected to know the fact that the wet had long since rendered the weapon useless. As for the old man, he stood rigid, as if petrified, with open mouth and staring eyes, and I saw that we had nothing to fear from him. I turned therefore to the younger man, who stood in the sergeant’s grip, the very picture of astonishment. Behind us the troopers crowded into the room.

“Now, my friend,” I said quietly, picking up the lantern from the ground—it had fallen from his hand—“I desire a word with you!”

“Who are you, and what do you want?” he stammered, when at last he found his tongue. That soldiers should rise up out of the night in the very centre of his master’s lands was a thing apparently beyond his power to grasp. He was a man of about forty, as near as I could judge, and he bore the look of one to whom good living came habitual. I did not anticipate having much trouble with him, but in this I proved to be mistaken.

“As to who I am,” I answered sharply, “I am a king’s officer; let that be sufficient for you! And for the rest, I have need of your assistance, and also some information. You are, I take it, steward to the Earl of Ingram, who, I understand, is at present with the man James Stuart in Ireland, and high in his favour?”

He looked at me, scowling, but he did not speak.

“Answer, will you!” cried the sergeant, thrusting[25] his scarred visage within a foot of the other’s head.

“Yes,” he replied sullenly, shrinking from the sergeant’s fierce face.

“Good,” I answered. “I see that we shall get on, my friend. You were speaking a while ago of a Frenchman. Nay, do not give yourself the trouble of denying it. He is still here?”

“And if so, what then?” he said suspiciously, heedless of the sergeant’s threatening look.

“Only that I desire speech of this same gentleman,” I answered, “and I have ridden far to get it. In the first place, how many servants are there in the house yonder?”

He hesitated for a moment, then:

“There are but a dozen,” he replied.

“Are you sure there are no more?” I said sharply. “The truth, man!”

“I have told you,” he answered sulkily; “and the half of these are women.”

“Very good,” I answered; “that is sufficient. You will now lead us to the house, and—for I see that you have the keys—you will show us how best to gain an entrance.”

“I’ll not do it,” he burst out on a sudden, to my astonishment, for I had not given the man credit for so much courage. “I tell you I will take no part in it! I will do nothing that shall injure my ladies!”

“You are a fool!” I said tartly, for I was fast losing patience. Time was passing, and I was anxious to get the business over in order to dry my wet clothes, which clung to me with a chilly persistency. Moreover, I[26] thought it more than probable that Cornet Graham would have already arrived ere this at the house, and, believing that some accident had surely befallen us, would proceed to execute his commission in his own way. In that case I had missed what credit there might be attached to the actual capture. “I have told you that it is with this gentleman I wish to speak. I have nothing to do with aught else.”

“Yet I will not do it,” he said doggedly. “You may find the key for yourself.”

“Perhaps the flame of yon candle across his wrists would make him alter his mind,” growled the sergeant.

I saw the man turn white at the words, but he uttered no sound. “Hark you, fellow!” I said harshly. “I have no time to waste in trifling. I will give you till I count ten to say if you will do as I desire, and I should recommend you to reconsider your decision, otherwise——”

I caught the sergeant’s eye. He grinned and commenced to unwind his sash. In the dead silence that followed, a silence broken only by the whistling of the wind without, that set the lanterns flickering and the shadows dancing on the walls, I began slowly to count. The troopers stood around, leaning on their swords, in keen expectation of that which was to come.

It was a strange scene upon which the lantern light fell. The mare regarding the intruders with a mild surprise, the prisoner in the centre, silent and sullen, and lastly, the ring of ruthless faces, upon which were stamped all the baser passions of cruelty and lust.

“Eight, nine”—I made a longer pause—“ten!”

[27]The man before me had neither moved nor spoken as yet, but now he broke out again:

“I will not do it! You may flog me first! I will say no more!”

The sergeant’s eye had been busy searching the room.

“We shall not flog you,” he said grimly. “Make your mind easy as to that. But,” he continued, “there is a hook above, I see, and a strong one. Here, one of you, bring me that rope yonder. I will teach him how we unloose tongues in Tangiers!”

The words seemed to arouse the steward to a sense of his danger, for he made an unexpected dash for the door. But the troopers were too quick for him. There was a short struggle, a volley of curses as the man was borne down and his arms pinioned behind his back. A trooper climbed upon the stall and flung the rope over the hook in the ceiling. A couple more dragged their prisoner across, and making a running noose, slipped it over his head, and three pairs of willing hands seized the other end of the rope, and the thing was done with a celerity of dispatch that bespoke long practice. They but awaited my signal. I was loth to give this, for I would have spared the man if I could, but I saw no other way to make him speak. I was about to give it, therefore, when there came an unexpected interruption. Up till now the old man I have before mentioned had stood a still and silent spectator of the scene being enacted, but seeing his companion standing with the rope round his neck, and reading for the first time the doom in store for him, he suddenly moved forward, striving to push his way to his side.

[28]“You devils!” he cried shrilly, “let the man go! Let him go, I say!”

“To your kennel, old Beelzebub!” cried a trooper roughly with a blow on the mouth that sent him reeling backwards, to fall beneath the horse’s feet, where he lay whimpering senilely among the straw.

I turned again to the prisoner.

“Once more,” I said shortly, “will you lead and gain us an entrance to the house—yes or no?”

His white lips quivered for answer, but no sound escaped them. He seemed like one dazed.

The sergeant looked inquiringly across at me. I nodded grimly and stepped through the open door. I was desirous of ascertaining if the fog had lifted, and there are some things it is better not to see. It was intensely dark outside the circle of light thrown by the lanterns, yet after standing for a short time probing the blackness with my eyes I thought that the mist had certainly grown somewhat thinner, for I could dimly make out the form of the bushes opposite me and the pathway at my feet running into the gloom. I made my way a short distance along this, keeping in touch with the wall upon my right. The rain was still falling heavily, and the wind moaned in the treetops above with a sound like the wailing of lost souls in pain. From the room behind me came one cry that pierced the fog and reached my ears above the gale, and then silence.

The sergeant was a persuasive man. It was in less than five minutes that, looking back, I saw his figure appear in the doorway. Shading his eyes with his hand,[29] he stood peering out into the darkness. I slowly retraced my steps.

It was not until I was at his side that he saw me. He gave a start at my sudden appearance; and held out his hand. “Here is the key,” he said with a grin; “and he has changed his mind.” I took the key and followed him into the room.

The steward lay upon the ground with blackened face and distorted features. They had taken the rope from round his neck and it now hung dangling from the hook above. He had the appearance of a man in the last extremity.

“You have gone too far,” I said, frowning. “The man is dying!”

“Not he,” the sergeant answered. “We did but give him an extra dance on air in case the way should slip his memory.”

He stooped as he spoke, and lifting the man’s body, propped him with his back against the stall; and picking up the bucket that lay beside the mare, he flung the contents upon his head. It had the desired effect. In less than five minutes the shadow faded from his face, his breathing grew more regular. Presently they raised him to his feet and—supported by a trooper on either side—he stood breathing heavily.

“Will you guide us now?” said the sergeant fiercely, “or must we string you up again?”

The man before us gave a slight gesture of assent. He was too far gone to speak.

“And play us no tricks,” the sergeant growled. “I[30] have made better men speak than you, though they were heathen—aye, and be silent too!” And he passed his hand across his throat with a gesture there was no mistaking.

I waited a few minutes longer for the knave to recover himself and while they bound the old man to the head of the stall, where he stood mumbling incoherent curses; and then, thrusting the lantern into the steward’s shaking hand, guarded by the troopers on either side, we set out on our way. I had thought that the house lay close at hand, but this was not the case. Now that we were in the open air, the cold wind and the rain beating upon his bare head had a reviving effect upon the steward, and he led us unfalteringly through the darkness. He turned sharply to the right; and by the flickering light cast by the lantern, I could see that we were upon a broad gravel walk and that the trees on either side had given place to well-kept lawns and beds of flowers, over which the wind swept boisterously.

Suddenly the lantern swung to the left; and a moment or two later the sergeant rapped out an oath.

“What is the matter?” I said sharply.

“We have left the path!” he cried.

I snatched the lantern from the steward’s hand and saw that the sergeant had spoken the truth. There was turf beneath our feet. A sudden suspicion of our guide crossed my brain. What if he should lead us once more to the brink of the cliff, and, true in his loyalty to the house he served, should cause us to perish, though the act should involve his own destruction. Such things had[31] been done, I knew, and he had proved himself to be a stubborn man. I threw the light upon his face.

“What is this?” I said harshly. “Are you playing us false, man?”

“No,” he answered sullenly. “There should be a fountain here.”

I bade the troopers keep behind me, and throwing the light upon the ground, moved slowly forwards, half expecting at each step to see some horrible abyss yawning at my feet. But nothing appeared until some fifty feet further I came once more to a gravel path, in the centre of which a white marble fountain loomed ghost-like through the fog. At a short distance from this stood a stone seat, its surface strewn with the petals of withered roses. I thrust the light back into the steward’s hand, and he struck off into a broader walk than any we had as yet traversed and which ascended, by means of three or four stone steps, in a succession of terraces, until, when we had travelled fully a quarter of a mile from where we started, we came at last to a little stone bridge spanning a narrow moat. I held the lantern over this and the light shone upon the dark surface below, covered, for the most part, with a thick growth of water-weed. The bridge gave entrance to a broader terrace beyond, across which loomed the dark outline of the house. I bade them now put out the lantern; and we crossed the terrace and stood beneath the walk of the building. To left and right of where we were standing the house stretched into the fog, dark and silent. There[32] was something almost sinister in its gloomy aspect, matching well with the black night without.

Stay; a little to our right I thought that I could see a shaft of light, and it was towards this that the steward directed his steps. It came from a heavily curtained window and lay a mere slit upon the gravel surface of the terrace. At the top the curtains had fallen somewhat apart, disclosing nothing to our view, however, beyond a glimpse of the brightly illumined ceiling of the room. I halted and put my lips to the steward’s ear. “What room is that?” I said softly.

“It is the dining hall,” he whispered in reply. “The man you seek is there.”

I noticed that the window was such as I had seen in France. It reached to the ground and opened upon the terrace. I left two troopers therefore to guard it, impressing them with the necessity of using the utmost vigilance. They took up their station one on either side, and we continued our way until the steward stopped at length before an arched doorway in the wall. I halted then, and waiting till a lull in the gale, raised my voice and gave the signal I had agreed upon with Cornet Graham. The melancholy cry went pealing into the night, and we stood in the darkness, straining our ears for a reply. But no answering cry came back to them, no sound from the silent house, save the patter of the rain upon the ivy-covered wall and the sobbing of the wind in its eaves and gables.

I waited no longer, therefore, but inserted the key in the lock before me. It was a massive door, nail-studded,[33] and it opened with a sullen creak as we quickly entered, carrying with us a breath of the fog and a shower of raindrops. We closed it quietly behind us, and so thick was its massive timber that the noise of the wind without came to our ears but faintly as from a distance. We stood in a narrow passage, giving place to a square, dimly lit hall, from which five or six doors opened. So far we had seen no one, but from a corridor on the right came the sound of voices with now and again a snatch of song.

I looked inquiringly at the steward.

“The servants’ quarters,” he whispered in return.

I signed to two or three of the men to take their stand at the head of this passage, and, with the others at my heels, crossed the hall to a door upon the left, from beneath which the light was shining. Then, sword in hand, I softly opened the door and we entered the room.

The interior was brilliantly lighted by a number of wax candles set in sconces against the walls, their light reflected by a cunning arrangement of broad mirrors that hung upon the deep oak-panelled surface behind them. Between these the light fell upon many a portrait of past earls of Cleeve, interspersed with arms of various countries and the trophies of the chase. Upon our right, three broad stairs, flanked on either side by a richly carved balustrade, led up to a little landing, on which, directly facing the steps, were a pair of folding doors. From this landing the stairway divided, ascending left and right to a gallery overhead, that ran along the whole length of that side of the hall. On our left were three or four heavily curtained windows. For the rest, the squares of bright-hued carpet lying on the polished oaken floor, the richness of the furniture and hangings, all bespoke the wealth of the owners, as the cut-glass bowls filled with the summer’s flowers, the open spinet upon which some leaves of music were scattered, denoted unmistakably the presence of women—and women of refinement and taste.

All this I took in, as it were, at a glance ere fixing my eyes upon the two persons who occupied the room.

[35]At the farther end, before a wide, stone chimney, in which a bright fire of logs was burning, a lady was seated in a high-backed chair, over which a tall man was leaning, conversing with her in low tones.

Their backs were towards us, and they did not move when I opened the door. Doubtless they thought it was some servant who entered. They were speedily undeceived.

“M. de Launay,” I cried clearly, “I arrest you in the name of his Majesty, William III.!”

Had a cannon-ball fallen suddenly into the room, it could not have occasioned a greater surprise.

The lady started to her feet with a low cry of fear, and so stood, gazing at us with startled eyes. As for the gentleman, he turned to face us, his sword half drawn from its sheath. But a second glance must have convinced him of the futility of resistance, for he let his hand fall to his side again. He was a handsome man in the prime of life, and was dressed in the latest fashion of the French Court. His suit of white flowered satin and gold-embroidered vest became him wonderfully; his peruke was of the largest, his cravat and the ruffles at his wrist of the finest lace; and there was an air of graceful elegance about him which birth and breeding alone give. He bore the look of one who had spent his life in the society of great men.

For a few seconds there was silence in the room, broken only by the howl of the wind without and the lashing of the rain against the window.

“Who are you?” he demanded, when at length he found[36] his voice. He spoke English well enough, though with a somewhat foreign accent.

“Permit me to explain,” I answered, turning to the lady, though still keeping a watchful eye upon the man before me. I now had leisure to observe her more closely. She was young, not more than twenty years of age, as I judged, and her gown of pink brocade served to display the slimness of her figure. A fair face, surrounded by its mass of flaxen curls, but one scarcely deserving the high praises that Cornet Graham had sung in my ears upon the road. As the thought of them recurred to me, I could barely repress a smile. I had seen many women more beautiful. “Do I address the Lady Lettice Ingram?” I said, doffing my hat.

“She is my sister,” she replied slowly. Her eyes were still dark with fear. In a moment I was minded of the steward’s words. I told myself that this was the Mistress Grace that he had mentioned.

“Madam,” I made haste to answer, “I beg that you will not be alarmed at this intrusion, which the exigencies of my errand alone warranted. My business is with this gentleman,” I continued, indicating the Frenchman, who stood, one white hand laid upon the hilt of his rapier. “M. de Launay, I am charged with your arrest by order of Sir Richard Danvers, governor of the west during his Majesty’s absence in Ireland.”

“Pest!” he said coolly. “But if I am not the person you mention. What if you have made a mistake, monsieur?”

“No mistake, M. le Marquis,” I answered firmly, “as[37] I am about to prove to you. Be good enough to carry your memory back some three years, and I think that you cannot have forgotten one Armand de Brissac and a certain duel in the Crown Tavern at Barcelona!”

For a moment he stared at me, a look of profound astonishment on his face.

“De Brissac? The Maître D’Armés?” he cried quickly.

“On that occasion,” I continued, “you staked somewhat heavily upon the issue and lost.”

“To poor D’Epernay, who fell at Walcourt. Certainly I remember the circumstances. But you—how is it that you?—I do not understand.” He looked at me more intently. “Pardieu!” he burst out, “I know you now! He was the finest swordsman in the French army, and you killed him in less than five minutes!”

I bowed low.

“That being the case, monsieur,” I answered, “I think you will admit that I have made no mistake as to your identity.”

“Readily,” he replied lightly. “And your name, monsieur? It has escaped my memory.”

“Adrian Cassilis,” I answered, “at your service! Captain in his Majesty’s Tangier Horse!”

“A famous regiment,” he said. “I congratulate you! I have had the pleasure of fighting against them both in France and Flanders.”

Again I bowed.

“Admitting then, M. Cassilis,” he continued, “that I am the man you mention, may I be permitted to ask what[38] is your purpose concerning me, and where you would take me?”

“To Exeter,” I answered, “in the first place.”

“And afterwards?” he said quickly.

“Doubtless my Lord Danvers will himself inform you,” I replied.

“You are discreet, monsieur!” he said, frowning. “At least you will not refuse to inform me with what offence I am charged?”

“All in good time, M. le Marquis,” I answered, shrugging my shoulders. “Be patient, I beg of you. You have been a soldier yourself. My duty is but to secure your person.”

“But, you have some idea!” he cried impatiently. “Is it not so? Be frank, man!”

“Possibly,” I answered curtly. “With the Stuart in Ireland and a French army at Dunkirk, it needs no long head to discover a reason for depriving so distinguished a soldier as M. de Launay of his present liberty.”

“Truly I should be flattered at my celebrity,” he answered lightly. “But if the liberty of every one of my countrymen at present in England is for the same reason to be so curtailed, you will require to enlarge your prisons, monsieur!”

I was about to reply to this, when——

“What is the meaning of this outrage?”

The words fell clearly and suddenly upon my ears.

I turned in the direction from which the voice proceeded, and I saw that the folding doors beneath the[39] gallery were wide open, and that a woman stood at the head of the stair.

She stood at the head of the stairway, in the full light of the candles, and as my eyes rested upon her face, the dangers and hardships of our journey, nay, the very errand upon which we had come, and the presence of the man at my side, all faded away, and I saw nothing but the face of the woman before me, while in my ears rang the words of the cornet: “She is accounted by some to be the loveliest woman in England.” And I knew that they had not lied.

She was clad in a grey-velvet riding dress, that revealed every curve of her faultless figure, silhouetted as she was against the semi-darkness of the corridor behind. Upon the clustering golden hair that framed her face was set the daintiest of three-cornered riding hats. But how to describe her beauty I know not. Words are but poor things at best, and how can I, a plain soldier, depict with justice that upon which the painters and poets of Europe have lavished the finest efforts of their genius! This only will I say: That in the proud poise of the lovely head, upon the haughty, glowing face, with its rich colouring heightened by her recent ride, was stamped the pride of birth and conscious beauty.

Oh, she was beautiful! A woman for the sake of whom a man might give his life and count it less than naught. A woman to gain whose love a man might sell his soul!

“I am waiting, sir!” she cried impatiently, as speechless I stood before her, dazzled by her beauty. Her voice was rich, if a trifle imperious; her every movement[40] instinct with a womanly grace. Descending the steps, she stood facing me not ten paces distant. And I saw her eyes—eyes of a dusky, violet hue flash ominously as she took in the details of the scene. Doubtless, splashed with mud as we were from head to heel, our clothes sodden with the wet, our faces streaked with scratches where the brambles had torn us—we must have appeared like denizens of the Pit itself.

Her words recalled me to myself with a start.

“Madam,” I stammered—and my voice sounded hoarse even to my own ears—“I crave your pardon for so intruding, but—That window is guarded, M. de Launay!” I broke off sharply.

He gave in at that.

“Pest!” he said with a shrug. “You think of everything, monsieur! I call you to witness, however, that I had given you no parole. Have you come out against me with an army?”

“I am too old a campaigner, monsieur,” I replied curtly, “to leave aught to chance.”

“Address yourself to me, sir!” my lady cried imperiously, “and in as few words as possible.”

I turned to where she stood, one gauntletted hand daintily upholding her trailing skirt. In the other she carried a short riding whip.

“To be brief then, madam,” I answered, “I am charged with an order for the arrest of M. de Launay.”

“M. de Launay is my guest,” she replied haughtily, “and were he King Louis himself I would not give him up!”

“Descending the steps, she stood facing me not ten paces distant”

[41]Doubtless the smallness of our numbers encouraged her in the thought that her servants might offer us effectual resistance. If so, she was speedily undeceived. Even as she spoke there came the sound of many footsteps in the hall without, accompanied by the clank of steel, and Cornet Graham and his troop entered the room.

“It appears to me, madam,” I said calmly, “that you have no option in the matter.”

She looked at me for a moment as if she could not believe her ears—as if I were less than the dirt beneath her feet. So long had she been accustomed to have her slightest wish obeyed, that now to have her will disputed was an experience as novel as it was humiliating.

“You would use force, sir?” she cried incredulously.

“As to that, madam,” I replied, “my answer is written behind me!” and I glanced significantly at the troopers.

“It is plainly written,” she replied quickly, with a woman’s ready wit. “Times are indeed changed,” she continued bitterly, “when we of the house of Ingram must submit to the bidding of the first beggar who carries a sword at his side! But it seems that we must obey the ruling powers, with whom even our own servants are in league!”

At this I could readily believe there was no enviable time ahead of the steward and he must have thought so, too, for with a sudden effort he shook off the slackened grasp of the troopers on either side and stepped quickly forward.

“My lady,” he cried, “what could I do? They would have hanged me!” and he pointed to his neck, round[42] which was a purple ring where the cord had cut into the flesh, plain to be seen by the dullest eyes, and the meaning of which could not be mistaken.

For a moment my lady gazed; then she drew herself to her full height and faced us, one hand pressed against her bosom, as if to restrain the passion that caused her figure to tremble and flashed from the depths of her wondrous eyes.

“And was this, sir,” she cried, “this in your orders—that you should not only break into my house, but should also vent your savage cruelty upon my inoffensive servants?”

Again I stood speechless before her, for anger served only to increase her loveliness.

“Inoffensive? A damned rebel!” growled the sergeant.

I silenced him with a look and turned once more to the woman before me.

“Pooh! madam,” I said coolly, for her words nettled me, “the man is not seriously hurt, and my duty must be my excuse.”

“Your duty!” she cried with intense scorn. “You had not dared this outrage had my brother, the earl, been present!”

“But he is not, madam,” I answered with a faint sneer. “I believe I am correct in saying that he is not even in England!”

“He is where every true and loyal gentleman should be,” she cried boldly—“in Ireland, fighting for his rightful sovereign, King James!”

I heard a low gasp escape the troopers behind me.[43] It might have been astonishment or of admiration at her boldness.

“You are frank, madam,” I replied, “and permit me to say it—somewhat indiscreet. But again I beg you to believe that the duty which thus forces me into your presence was as unsought by me as it is distasteful.”

“I do not believe you,” she said proudly. “And you may spare me your apologies, sir! There is never wanting an instrument base enough to execute any deed of injustice!”

Her words stung me.

“Very well, madam,” I replied; “then there is nothing further to be said. M. de Launay,” I continued, “I must trouble you for your sword. I regret that my leniency will not so far permit me to allow you to retain it, but give me your parole that you will attempt no escape upon the road and you shall ride with all freedom. Also,” I added, “I should recommend you to bring your cloak, monsieur. The weather is inclement.”

“But pardon, M. Cassilis,” he broke out, as a sudden gust of wind shook the casements and sent the raindrops rattling on the glass, “you do not mean to ride to Exeter on such a night as this!”

“By no means,” I answered. “But there is a good inn here, I am told. We shall be there to-night, monsieur, and start at daybreak.”

“In that case,” my lady cried, “he shall stay here to-night.”

“That is as I choose, madam,” I answered coldly, “and I do not choose.”

[44]I could see that to be checked, thwarted, made to feel of no account, here in the place where by virtue of her birth and beauty she had held undisputed sway, was galling to her pride beyond endurance. I could see it, I say, and I rejoiced in the knowledge.

“Your parole, monsieur!” I said once more, turning to the marquis.

“Since I have no choice in the matter,” he answered testily, “you have it. On the honour of a De Launay!” he added proudly.

I bowed.

“That is sufficient, monsieur,” I replied. “But pardon me,” I continued lightly; “you say that you have no choice in the matter. On the contrary, there is another alternative. I am offering you the treatment of a gentleman; if you prefer it, however, you may go bound to a horse like any common felon.”

He looked at me very sourly, but he did not speak. Instead, he unbuckled his sword and threw it with an ill grace upon the floor, and at a sign from me, a trooper stepped forward and picked it up. I glanced at my lady with, I doubt not, some of the triumph I felt showing in my eyes. I was so completely the master of the situation.

“Believe me, monsieur,” I said, “I take but the precaution that my warrant enjoins. You may read it for yourself if you so desire.”

“It is of no consequence,” he answered with a wave of the hand.

“But it is of consequence to me, monsieur!” my lady[45] cried wrathfully. “I am the mistress of this house and the guardian of all pertaining to its honour. Show me this warrant, if indeed you have one!” she added, turning suddenly upon me.

I sheathed my sword, and with flushed face and trembling fingers I drew the paper from my breast and held it out to her. But she stepped backwards with such a look of proud disdain upon her lovely face that my hand dropped involuntarily to my side. For a moment she stood thus, searching my eyes and enjoying, perhaps, my confusion, for I saw that she would not take it from my hand; then she motioned to the steward who stood near.

“Give it to me!” she said proudly.

He took the paper from my hand and she opened it and glanced quickly at its contents.

On a sudden she broke into a bitter laugh.

“‘By my authority,’” she said, reading. She looked up, her eyes aflame. “We are indeed fallen low when we must obey the authority of such men as my Lord Danvers!—of Sir Richard Danvers, drunkard and libertine! That is how I treat his authority!” She tore the paper across and across and flung the pieces at her feet. “And now begone, sir!” she continued, pointing imperiously to the door. “Begone! you and your red-coated rabble!”

For a moment I was too astounded to speak, but I heard a low murmur from the men behind me, and the sound recalled me to myself.

“Certainly I will be going, madam,” I replied. “I[46] could no longer stay in a house where so little respect is paid to the king’s authority. And I am not at all sure,” I continued slowly, “that I should be exceeding my duty if I were to arrest you also!”

“Arrest me?”

The words sprang from her lips in a tone of blank amazement, then she drew her queenly figure erect and gazed at me with such a tempest of wrath and scorn in her eyes as no words of mine can picture, and I saw her breast heave with the passion she strove in vain to control. I could well believe that never previously in all her life had she been so addressed.

“Certainly!” I answered harshly. “You seem to forget, madam,” I continued, pointing to the fragments of paper that lay between us, “that you have committed nothing short of treason in so destroying the king’s warrant. But I have no time to waste further words upon you!” I added rudely; for I saw how I could hurt her pride.

“The king’s authority!” she cried passionately. “The authority that sends such men as you to insult women! I would to God my servants had been present, for they should have flogged you, sir—flogged you from the village, and the ragged hirelings with you!”

I stood hand on hip not three paces from her, and I fixed my eyes insolently upon her lovely face.

“I do not doubt their willingness under your tuition, madam,” I answered coolly, “but only their ability to do so; for,” I continued slowly, as a coarse laugh broke from the men behind me, “if they are no better when it[47] comes to blows than King James, whom they serve, of whose courage we have lately had an example beneath the walls of Derry, there would be more about them of flight than fight!”

For a moment she gazed at me with panting breath and quivering nostrils; then moved by my words beyond restraint:

“You liar!” she cried, and throwing into the words all her concentrated anger, before I could guess her purpose she raised the riding whip in her hand and struck me heavily across the face.

To this day I take it to my credit that no oath escaped my lips. A thin trickle of blood ran down my cheek. But ere she could repeat the blow I caught her wrist and so stood facing her while one might count a score.

What she read in my own eyes I know not, but in the depths of hers I read impotent passion, scorn, and hate, but not a trace of fear.

I loosened her wrist—even in my pain its soft touch thrilled me—and I stepped backwards, wiping the warm blood from my face.

“Madam,” I said very quietly, “one day I will repay you for that blow with tenfold interest!”

“Threats!” she answered scornfully, “and to a woman!”

I turned away.

“Monsieur,” I said to the marquis, who had stood a silent spectator of the scene, and still speaking in the same level tones, “if you are ready to accompany us, we will set out.”

“I am at your service,” he answered, taking a cloak[48] from a chair in one corner of the room and wrapping himself in its folds. Then he advanced to the ladies to make his adieux.

“Farewell, madam,” he said, bowing with courtly grace to my lady, and raising her hand to his lips.

“M. de Launay,” she replied, “I can find no words to apologise for the insult offered you in this house.”

“Madame,” the marquis answered gallantly, “I beg that you will banish the episode from your memory.”

“That is impossible,” she said quickly. “That guest of ours should be so served, and to be powerless to prevent it! But say, rather, au revoir, monsieur,” she continued, with kindling eyes, “for I, too, shall ride to Exeter to-morrow, and will myself interview Sir Richard Danvers on your behalf! We shall see whether the name of Ingram does not still possess weight sufficient to annul this outrage and to punish the perpetrators!” And she shot a scornful glance in my direction.

“Very good, madam,” I answered, “only in that case I shall ride with you. I have no desire,” I continued with a sneer, “that my Lord Danvers should hear anything but the truth.”

“Then I pray you keep behind me, sir!” she replied haughtily. “I would not have you taken for lackey of mine!”

I made no reply to this. What reply could I make? Instead, I gave a sharp order and the troopers fell into place, the marquis in their midst. They filed through the open doorway with the clank of steel, and the tramp of their footsteps died away down the hall. I waited[49] until the last one had left the room and then prepared to follow.

Once as I crossed the threshold I looked back, and the light fell upon the tall figure of my lady, her sister at her side, then the door closed upon the room and its inmates, and passing quickly through the hall, in which a little crowd of scared servants had gathered, I went out into the night. Outside, at the foot of the steps leading to the main entrance, I found the troopers waiting, the light from the open doorway shining upon their horses, my own amongst the number.

I bade one of the men give up his mount to the marquis, and collecting the men I had stationed upon the terrace, I climbed into the saddle, and so for the first time I left Cleeve.

The fog had collected somewhat, though it was still very dark, and the brightly lighted room from which we had come rendered the blackness that surrounded us more opaque.

For myself I was content to resign the lead to Cornet Graham and to follow behind the others with only my thoughts for company. And if ever there was all hell in a man’s heart, it was in mine that night.

For now that I was alone, now that I had no longer to keep up appearances, I gave way to the passion I had so far restrained. That I—I of all men, should be struck by a woman! And in public! As the thought of the men in front who had been witnesses of my disgrace recurred to me, I ground my teeth with anger and cursed this woman who had brought me to shame.

[50]But bitterly, bitterly should she repent the blow! Oh, to hurt her! to humble her pride! to see her at my feet begging for mercy—and to refuse it! I gloated over the thought, and I swore in my heart that I would not spare her in the hour of my triumph one throb of the pain I was now enduring. She should drink the cup of my revenge to the bitterest dregs; and so taken up was I with these thoughts that it was not until I saw the lights in the windows of the houses on either side of me that I realised that we had reached the village.

I spurred forward then and overtook the troop in front. From the length of the street and the size of the houses I saw that the place was larger than I had been given to understand. Here and there, at the trampling of our horses’ feet, windows were opened, and dark figures appeared in the doorways, or ran out, heedless of the falling rain, into the street. But the sight of the troopers’ swarthy faces and of the hated uniform they wore drove them swiftly indoors again. For though it was June of the year 1690, and Dutch William had now been two years upon the throne, yet so great was the terror which the “Tangier devils” had inspired throughout the West, both in friend and foe alike, at the time of Monmouth’s ill-fated rebellion, that Catholics though the villagers were, they knew by past experience that these very troopers who had fought for James at Sedgemoor and elsewhere were now equally ready to plunder them as Papists and Jacobites in the name of William; and behind their barred doors there was many a one, I wot, that night[51] who trembled for the loss of such goods as he possessed and for the safety of his women folk.

At the end of the street the cornet turned sharply to the right and entered a square courtyard, at the opposite side of which stood an old-fashioned inn.

A blaze of light came from its windows, through one of which could be distinguished the dark figures of the troopers of De Brito’s party. We drew rein before the door, and almost ere we could dismount the landlord stood upon the steps.

“Welcome, gentlemen,” he said, bowing. “What is your pleasure?”

He was a round-faced, portly man, with an air somewhat above that of the keeper of a country inn. There was a nameless something about him that told me he had at one time been a soldier.

“You can find room for us to-night, I suppose?” I answered.

“Well,” he replied slowly, “my rooms are small, but if a couple of lofts——”

“That will do for us,” the sergeant said gruffly. “Better a board than six feet of earth on such a night.”

“Aye, and good liquor in plenty to soften it,” cried a trooper, and the men laughed.

“You shall find no complaint with that, I promise you,” said the landlord. “There are wines to suit all tastes, and as for my cider, ’tis second to none in all Devonshire.”

“To the devil with your cider!” said a trooper roughly. “Give us brandy, hot, and of the best, if you would[52] keep this hen coop from being burned round your ears!”

“And a pretty wench to serve it!” cried another.

“As you please, gentlemen! As you please!” the landlord hastened to say. “None should know better than I how to treat you. I have cognac here—the best out of France. But come inside, gentlemen, and my men shall look to your horses.” He turned and led the way indoors.

In a square, stone-paved room on the right of the passage we found De Brito’s troopers, a plentiful supply of ale upon the low tables before them, who greeted their comrades with boisterous shouts of welcome.

“Would it not be advisable, monsieur, to seek another apartment?” said M. de Launay. “Your men are gallant fellows, but save on the field of battle, I prefer them at a distance.”

“By all means,” I answered. “You have another room?” I said, turning to the landlord.

“This way,” he replied, leading me, closely followed by Cornet Graham and the marquis, down a narrow, low-ceilinged passage.

“You have seen service yourself?” I said sharply.

“Aye, years ago,” he replied briefly. “I fought for the Swede.”

He stopped before a door upon the left, and with many apologies for his lack of space, ushered us into what proved to be the kitchen of the inn. It was a large room well stocked with articles pertaining to its character. Here a row of brightly polished pans, there a[53] score of reeves of onions, while from a hook in one corner hung a well-cured ham.

Before a great fire of logs De Brito was sitting, a leather flask and tankard upon a table at his side, to the former of which I saw he had been paying liberal attention. He looked up as we entered.

“So you’ve come at last,” he said thickly. “Landlord, bring glasses for these gentlemen, and more brandy. What the devil!” he broke off suddenly, catching sight of my face. “Did the dove turn out to be a hawk, after all? Well, she has not marred your beauty!” and he laughed insolently.

But I could brook no more.

All the passion that was smouldering in my heart flashed into sudden flame.

“Curse you!” I cried, and I caught the tankard from the table and flung the contents in his face; then, drawing my sword, I placed myself on guard.

He dashed the liquor from his eyes (it had been half full of the raw spirit) and sprang to his feet with a furious oath.

But he had reckoned without his cost. Even as he snatched his blade from the table where he had laid it the fumes of the brandy that he had been drinking heavily mounted to his brain. He staggered forward, his knees gave way under him, and he fell to the floor, where he lay, unable to rise.