The Project Gutenberg EBook of Prisoners of Chance, by Randall Parrish

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Prisoners of Chance

The Story of What Befell Geoffrey Benteen, Borderman,

through His Love for a Lady of France

Author: Randall Parrish

Illustrator: The Kinneys

Release Date: February 25, 2006 [EBook #17856]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PRISONERS OF CHANCE ***

Produced by Al Haines

Author of "When Wilderness was King," "My Lady of the North," "Bob Hampton of Placer," etc.

The manuscript of this tale has been in my possession several years. It reached me through natural lines of inheritance, but remained nearly forgotten, until a chance reading revealed a certain historic basis; then, making note of correspondences in minor details, I realized that what I had cast aside as mere fiction might possess a substantial foundation of fact. Impelled by this conviction, I now submit the narrative to public inspection, that others, better fitted than I, may judge as to the worth of this Geoffrey Benteen.

According to the earlier records of Louisiana Province, Geoffrey Benteen was, during his later years, a resident of La Petite Rocher, a man of note and character among his fellows. There he died in old age, leaving no indication of the extent of his knowledge, other than what is to be found in the yellowed pages of his manuscript; and these afford no evidence that this "Gentleman Adventurer" possessed any information derived from books regarding those relics of a prehistoric people, which are widely scattered throughout the Middle and Southern States of the Union and constitute the grounds on which our century has applied to the race the term "Mound Builders."

Apparently in all simplicity and faithfulness he recorded merely what he saw and heard. Later research, antedating his death, has seemingly proven that in the extinct Natchez tribe was to be found the last remnant of that mysterious and unfortunate race.

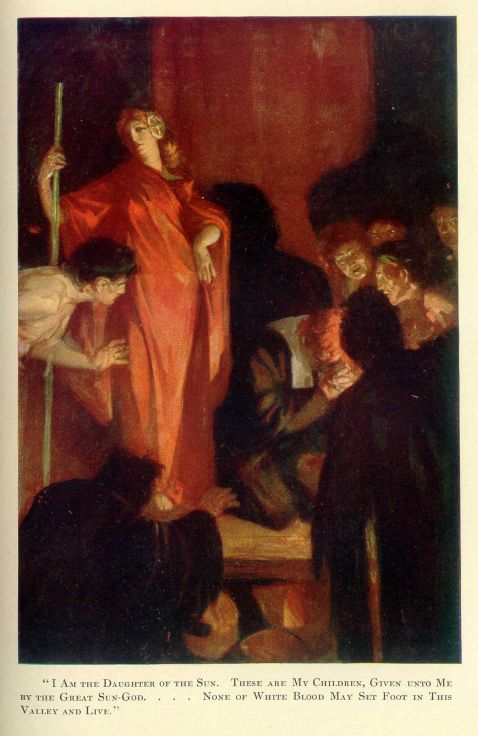

Who were the Mound Builders? No living man may answer. Their history—strange, weird, mysterious—stretches backward into the dim twilight before tradition, its sole remaining record graven upon the surface of the earth, vaguely guessed at by those who study graves; their pathetic ending has long been pictured in our country's story as occurring amid the shadows of that dreadful midnight upon the banks of the Ocatahoola, when vengeful Frenchmen put them to the sword. Whence they came, whether from fabled Atlantis, or the extinct Aztec empire of the South, no living tongue can tell; whither fled their remnant,—if remnant there was left to flee,—and what proved its ultimate fate, no previous pen has written. Out from the darkness of the unknown, scarcely more than spectral figures, they came, wrote their single line upon the earth's surface, and vanished, kings and people alike sinking into speechless oblivion.

That Geoffrey Benteen witnessed the tragic ending of this strange people I no longer question; for I have compared his narrative with all we moderns have learned regarding them, as recorded in the pages of Parkman, Charlevoix, Du Pratz, and Duponceau, discovering nothing to awaken the slightest suspicion that he dealt with other than what he saw. More, I have traced with exactitude the route these fugitives followed in their flight northward, and, although the features of the country are greatly altered by settlements of nearly two hundred years, one may easily discern evidence of this man's honesty. For me it is enough to feel that I have stood beside the massive tomb of this mysterious people—a people once opulent and powerful, the warriors of forgotten battle-fields, the builders of lost civilizations, the masters of that imperial domain stretching from the Red River of the North to the sea-coast of the Carolinas; a people swept backward as by the wrath of the Infinite, scourged by famine, decimated by pestilence, warred against by flame, stricken by storm, torn asunder by vengeful enemies, until a weakened remnant, harassed by the French sword, fled northward in the night to fulfil the fate ordained of God, and finally perished amid the gloomy shadows of the grim Ozarks, bequeathing to the curious future neither a language nor a name.

But this I leave with Geoffrey Benteen, and turn to my own simpler task, a review of the peculiar circumstances leading up to this narrative, involving a brief chapter from the records of our Southwest.

The early history of the Province of Louisiana is so complicated by rapid changes in government as to confuse the student, rendering it extremely difficult to comprehend correctly the varied and conflicting interests—aristocratic, official, and commercial—actuating her pioneer colonists. The written records, so far as translated and published, afford only a faint reflection of the varied characteristics of her peculiar, changing population. The blue-eyed Arcadian of her western plateaus, yet dreaming upon his more northern freedom; the royalist planter of the Mississippi bottoms, proud of those broad acres granted him by letters-patent of the King; the gay, volatile, passionate Creole of the town, one day a thoughtless lover of pleasure, the next a truculent wielder of the sword; the daring smugglers of Barataria, already rapidly drifting into open defiance of all legal restraint; together with the quiet market gardeners of the Côte-des-Allemands, formed a heterogeneous population impossible to please and extremely difficult to control.

Varied as were these types, yet there were others, easy to name, but far more difficult to classify in their political relationships—such as priests of the Capuchin order; scattered representatives of Britain; sailors from ships ever swinging to the current beside the levee; sinewy backwoodsmen from the wilds of the Blue Ridge; naked savages from Indian villages north and east; raftsmen from the distant waters of the Ohio and Illinois, scarcely less barbarian than those with redder skin; Spaniards from the Gulf islands, together with a negro population, part slave, part free, nearly equal in point of numbers to all the rest.

And over all who was the master?

It would have been difficult at times to tell, so swiftly did change follow change—Crozat, Law, Louis the Fifteenth, Charles the Third, each had his turn; flag succeeded flag upon the high staff which, ever since the days of Bienville, had ornamented the Place d'Armes, while great merchants of Europe played the occupants of thrones for the bauble of this far western province, whose heart, nevertheless, remained forever faithful to sunny France.

As late as 1768 New Orleans contained scarcely more than three thousand two hundred persons, a third of these being black slaves. Sixty-three years previously Bienville had founded Louisiana Province, making choice of the city site, but in 1763 it suited the schemes of him, who ruled the destinies of the mother country, to convey the yet struggling colony into the control of the King of Spain. It was fully two years later before word of this unwelcome transfer reached the distant province, while as much more time elapsed ere Don Antonio de Ulloa, the newly appointed Spanish governor, landed at New Orleans, and, under guard of but two companies of infantry, took unto himself the reins. Unrest was already in the air,—petitions and delegations laden with vehement protests crossed the Atlantic. Both were alike returned, disregarded by the French King. Where it is probable that a single word of wise counsel, even of kindly explanation, might have calmed the rising tumult, silence and contempt merely served to aggravate it.

It has been written by conscientious historians that commercial interests, not loyalty to French traditions, were the real cause of this struggle of 1768. Be that as it may, its leaders were found in the Superior Council, a body of governors older even than New Orleans, of which the patriotic Lafrénière was then the presiding officer, and whose membership contained such representative citizens as Foucault, Jean and Joseph Milhet, Caresse, Petit, Poupet, a prominent lawyer. Marquis, a Swiss captain, with Bathasar de Masan, Hardy de Boisblanc, and Joseph Villere, planters of the upper Mississippi, as well as two nephews of the great Bienville, Charles de Noyan, a young ex-captain of cavalry, lately married to the only daughter of Lafrénière, and his younger brother, a lieutenant in the navy.

On the twenty-seventh of October, 1768, every Frenchman in Louisiana Province was marching toward New Orleans. That same night the guns at the Tehoupitoulas Gate—the upper river corner—were spiked; while yet farther away, along a narrow road bordering the great stream, armed with fowling pieces, muskets, even axes, the Arcadians, and the aroused inhabitants of the German coast, came sweeping down to unite with the impatient Creoles of the town. In the dull gray of early morning they pushed past the spiked and useless cannon, and, with De Noyan and Villere at their head, forced the other gates and noisily paraded the streets under the fleur de lis. The people rose en masse to greet them, until, utterly unable to resist the rising tide of popular enthusiasm, Ulloa retired on board the Spanish frigate, which slipped her cables, and came to anchor far out in the stream. Two days later, hurried no doubt by demands of the council, the governor set sail for the West Indies, leaving the fair province under control of what was little better than a headless mob.

For now, having achieved success, the strange listlessness of the Southern nature reasserted itself, and from that moment no apparent effort was made to strengthen their position—no government was established, no basis of credit effected, no diplomatic relations were assumed. They had battled for results like men, yet were content to play with them like children. For more than seven months they thus enjoyed a false security, as delightful as their sunny summer-time. Then suddenly, as breaks an ocean storm, that slumbering community was rudely aroused from its siestas and day-dreaming by the report that Spaniards were at the mouth of the river in overwhelming force.

Confusion reigned on every hand; scarcely a hundred men rallied to defend the town; yet no one fled. The Spanish fleet consisted of twenty-four vessels. For more than three weeks they felt their uncertain way around the bends of the Mississippi, and on the eighteenth of August, 1769, furled their canvas before the silent batteries. Firing a single gun from the deck of his flag-ship, the frigate "Santa Maria," Don Alexandro O'Reilly, accompanied by twenty-six hundred chosen Spanish troops and fifty pieces of artillery, landed, amid all the pomp of Continental war, taking formal possession of the province. That night his soldiers patrolled the streets, and his cannon swept the river front, while not a Frenchman ventured to stray beyond the doorway of his home.

Within the narrow space of two days the iron hand of Spain's new Captain-General had closed upon the leaders of the bloodless insurrection, his judgments falling with such severity as to earn for him in the annals of Louisiana the title of "Cruel O'Reilly." Among those of the revolutionists before mentioned, Petit, Masan, Doucet, Boisblanc, Jean Milhet, and Poupet were consigned to Moro Castle, Havana, where they remained a year, and then were stripped of their property and forbidden ever again to enter the province of Louisiana. The younger Bienville escaped with the loss of his fortune. Foucault met his fate resisting the guard on board the "Santa Maria," where he was held prisoner; while Lafrénière, De Noyan, Caresse, Marquis, and Joseph Milhet were condemned to be publicly hanged. The earnest supplication, both of colonists and Spanish officials, shocked by the unjust severity of this sentence, sufficed to save them from the disgrace of the gallows, but fated them to fall before the volley of a file of grenadiers.

With the firing of the sunset gun the evening of their last earthly day, the post-captain visited the condemned men, and spoke with each in turn; they numbered five. All through the dark hours of that night heavily armed sentries stood in the narrow passageway before nail-studded doors, while each hour, as the ship's bell struck, the Commandant of Marine peered within each lighted apartment where rested five plainly outlined forms. With the first gray of the dawn the unfortunate prisoners were mustered upon deck, but they numbered only four. And four only, white faced, yet firm of step and clear of eye, stood an hour later with backs to the rising sun and hearts to the levelled rifles, and when the single volley had echoed and reechoed across the wide river, the white smoke slowly lifting and blown away above the trees, only four lifeless bodies lay closely pressed against the red-brick wall—the fifth condemned man was not there: Chevalier Charles de Noyan had escaped his fate. Like a spirit had he vanished during those mysterious hours between midnight and dawn, leaving no trace of his going save a newly severed rope which hung dangling from a foreyard.

But had he escaped?

That morning—as we learn from private letters sent home by officers of the Spanish fleet—there came to the puzzled O'Reilly a report that in the dense blackness of that starless night a single boat sought to slip silently past beneath the deep shadows of the upper battery. Unhalting in response to a hail of the sentry, a volley was hastily fired toward its uncertain outline, and, in the flare of the guns, the officer of the guard noted the black figure of a man leap high into air, and disappear beneath the dark surface of the river. So it was the Captain-General wrote also the name "Charles de Noyan" with those of the other four, endorsing it with the same terse military record, "Shot at sunrise."

Nor since that fateful hour has the world known otherwise, for, although strange rumors floated down the great river to be whispered about from lip to lip, and New Orleans wondered many a long month whither had vanished the fair young wife, the daughter of Lafrénière, yet no authentic message found its way out of the vast northern wilderness. For nearly one hundred and fifty years history has accepted without question the testimony of the Spanish records. The man who alone could tell the strange story was in old age impelled to do so by a feeling of sacred duty to the dead; and his papers, disarranged, ill-written, already yellowed by years, have fallen to my keeping. I submit them without comment or change, save only as to the subdivision into chapters, with an occasional substitution for some old-time phrase of its more modern equivalent. He who calls himself "Geoffrey Benteen, Gentleman Adventurer," shall tell his own tale.

R. P.

I am Geoffrey Benteen, Gentleman Adventurer, with much experience upon the border, where I have passed my life. My father was that Robert Benteen, merchant in furs, the first of the English race to make permanent settlement in New Orleans. Here he established a highly profitable trade with the Indians, his bateaux voyaging as far northward as the falls of the Ohio, while his influence among the tribesmen extended to the eastern mountains. My mother was of Spanish blood, a native of Saint Augustine, so I grew up fairly proficient in three languages, and to them I later added an odd medley of tribal tongues which often stood me in excellent stead amid the vicissitudes of the frontier. The early death of my mother compelled me to become companion to my father in his wanderings, so that before I was seventeen the dim forest trails, the sombre rivers, and the dark lodges of savages had grown as familiar to me as were the streets and houses of my native town. Hence it happened, that when my father fell the victim of a treacherous blow, although he left to my care considerable property and a widely scattered trade, I could not easily content myself with the sameness of New Orleans; there I felt almost a stranger, ever hungering for the woods and the free life of the mountains.

Yet I held myself to the work in hand until successful in straightening out the tangled threads, and might have remained engaged in peaceful traffic until the end of life, had it not been for a misunderstanding with her who held my heart in captivity to her slightest whim. It matters little now the cause of the quarrel, or where rested the greater blame; enough that its occurrence drove me forth reckless of everything, desirous only to leave all of my own race, and seek amid savage environment and excitement forgetfulness of the past.

It was in September of the year 1769—just forty-eight years ago as I write—that I found myself once again in New Orleans, feeling almost a stranger to the town, except for the few rough flatboat-men in company with whom I had floated down the great river. Five years previously, heartsick and utterly careless of life, I had plunged into the trackless wilderness stretching in almost unbroken virginity to north and east, desiring merely to be left alone, that I might in solitude fight out my first grim battle with despair, saying to myself in all bitterness of soul that never again would I turn face to southward or enter the boundaries of Louisiana Province. During those years, beyond reach of news and the tongue of gossip, I wandered aimlessly from village to village, ever certain of welcome within the lodges of Creeks and Shawnees, or farther away amid those little French border towns dotting the Ohio and the Illinois, constantly feeling how little the world held of value since both my parents were gone, and this last blow had fallen. I loved the free, wild life of the warriors with whom I hunted, and the voyageurs beside whom I camped, and had learned to distrust my own race; yet no sooner did I chance to stand again beside the sweeping current of the broad Mississippi, than I was gripped by the old irresistible yearning, and, although uninspired by either hope or purpose, drifted downward to the hated Creole town.

I had left it a typical frontier French city, touched alike by the glamour of reflected civilization and the barbarism of savagery, yet ever alive with the gayety of that lively, changeable people; I returned, after those five years of burial in forest depths, to discover it under the harsh rule of Spain, and outwardly so quiet as to appear fairly deserted of inhabitants. The Spanish ships of war—I counted nineteen—lay anchored in the broad river, their prows up stream, and the gloomy, black muzzles of their guns depressed so as to command the landing, while scarcely a French face greeted me along the streets, whose rough stone pavements echoed to the constant tread of armed soldiers.

Spanish sentries were on guard at nearly every corner. Not a few halted me with rough questioning, and once I was haled before an officer, who, hearing my story, and possibly impressed by my proficiency in his language, was kind enough to provide me with a pass good within the lines. Yet it proved far from pleasant loitering about, as drunken soldiers, dressed in every variety of uniform, staggered along the narrow walks, ready to pick a quarrel with any stranger chancing their way, while groups of officers, gorgeous in white coats and gold lace, lounged in shaded corners, greeting each passer-by with jokes that stung. Every tavern was crowded to the threshold with roistering blades whose drunken curses, directed against both French and English, quickly taught me the discretion of keeping well away from their company, so there was little left but to move on, never halting long enough in one place to become involved in useless controversy.

It all appeared so unnatural that I felt strangely saddened by the change, and continued aimlessly drifting about the town as curiosity led, resolved to leave its confines at the earliest opportunity. I stared long at the strange vessels of war, whose like I had never before seen, and finally, as I now remember, paused upon the ragged grass of the Place d'Armes, watching the evolutions of a battery of artillery. This was all new to me, representing as it did a line of service seldom met with in the wilderness; and soon quite a number of curious loiterers gathered likewise along the edge of the parade. Among them I could distinguish a few French faces, with here and there a woman of the lower orders, ill clad and coarse of speech. A party of soldiers, boisterous and quarrelsome from liquor, pressed me so closely that, hopeful of avoiding trouble, I drew farther back toward the curb, and standing thus, well away from others, enjoyed an unobstructed view across the entire field.

The battery had hitched up preparatory to returning to their quarters before I lost interest in the spectacle and reluctantly turned away with the slowly dispersing crowd. Just then I became aware of the close proximity of a well-dressed negro, apparently the favored servant in some family of quality. The fellow was observing me with an intentness which aroused my suspicion. That was a time and place for exercising extreme caution, so that instinctively I turned away, moving directly across the vacated field. Scarcely had I taken ten steps before I saw that he was following, and as I wheeled to front him the fellow made a painful effort to address me in English.

"Mornin', sah," he said, making a deep salutation with his entire body. "Am you dat Englisher Massa Benteen from up de ribber?"

Leaning upon my rifle, I gazed directly at him in astonishment. How, by all that was miraculous, did this strange black know my name and nationality? His was a round face, filled with good humor; nothing in it surely to mistrust, yet totally unknown to me.

"You speak correctly," I made reply, surprise evident in the tones of my voice. "I have no reason to deny my name, which is held an honest one here in New Orleans. How you learned it, however, remains a mystery, for I never looked upon your face before."

"No, sah; I s'pects not, sah, 'cause I nebber yet hab been in dem dere parts, sah. I was sent yere wid a most 'portant message fer Massa Benteen, an' I done reckon as how dat am you, sah."

"An important message for me? Surely, boy, you either mistake, or are crazy. Yet stay! Does it come from Nick Burton, the flatboat-man?"

"No, sah; it am a lady wat sent me yere."

He was excessively polite, exhibiting an earnestness which caused me to suspect his mission a grave one.

"A lady?"

I echoed the unexpected word, scarcely capable of believing the testimony of my own ears. Yet as I did so my heart almost ceased its throbbing, while I felt the hot blood rush to my face. That was an age of social gallantry; yet I was no gay courtier of the town, but a hunter of the woods, attired in rough habiliments, little fitted to attract the attention of womanly eyes amid the military glitter all about.

A lady! In the name of all the gods, what lady? Even in the old days I enjoyed but a limited circle of acquaintance among women. Indeed, I recalled only one in all the wide province of Louisiana who might justly be accorded so high an appellation even by a negro slave, and certainly she knew nothing of my presence in New Orleans, nor would she dream of sending for me if she did. Convinced of this, I dismissed the thought upon the instant, with a smile. The black must have made a mistake, or else some old-time acquaintance of our family, a forgotten friend of my mother perhaps, had chanced to hear of my return. Meanwhile the negro stood gazing at me with open mouth, and the sight of him partially restored my presence of mind.

"Is she English, boy?"

"No, sah, she am a French lady, sah, if ebber dar was one in dis hyar province. She libs ober yonder in de Rue Dumaine, an' she said to me, 'Yah, Alphonse, you follow dat dar young feller wid de long rifle under his arm an' de coon-skin cap, an' fotch him hyar to me!' Dem am de bery words wat she done said, sah, when you went by our house a half-hour ago."

"Is your mistress young or old?"

The black chuckled, his round face assuming a good-natured grin.

"Fo' de Lawd, Massa, but dat am jest de way wid all you white folks!" he ejaculated. "If she was ol', an' wrinkled, an' fat, den dat settle de whole ting. Jest don't want to know no mor'."

"Well," I interrupted impatiently, "keep your moralizing to yourself until we become better acquainted, and answer my question—Is the woman young?"

My tone was sufficiently stern to sober him, his black face straightening out as if it had been ironed.

"Now, don't you go an' git cross, Massa Benteen, case a laugh don't nebber do nobody no hurt," he cried, shrinking back as if expecting a blow. "But dat's jest wat she am, sah, an' a heap sweeter dan de vi'lets in de springtime, sah."

"And she actually told you my name?"

"Yas, sah, she did dat fer suah—'Massa Geoffrey Benteen, an Englisher from up de ribber,' dem was her bery words; but somehow I done disremember jest persactly de place."

For another moment I hesitated, scarcely daring to utter the one vital question trembling on my lips.

"But who is the lady? What is her name?" As I put the simple query I felt my voice tremble in spite of every effort to hold it firm.

"Madame de Noyan, sah; one ob de bery first famblies. Massa de Noyan am one ob de Bienvilles, sah."

"De Noyan? De Noyan?" I repeated the unfamiliar name over slowly, with a feeling of relief. "Most certainly I never before heard other."

"I dunno nothin' 'tall 'bout dat, Massa, but suah's you born dat am her name and Massa's; an' you is de bery man she done sent me after, fer I nebber onct took my eyes off you all dis time."

There remained no reasonable doubt as to the fellow's sincerity. His face was a picture of disinterested earnestness as he fronted me; yet I hesitated, eying him closely, half inclined to think him the unsuspecting representative of some rogue. That was a time and place where one of my birth needed to practise caution; racial rivalry ran so high throughout all the sparsely settled province that any misunderstanding between an English stranger and either Frenchman or Spaniard was certain to involve serious results. We of Northern blood were bitterly envied because of commercial supremacy. I had, during my brief residence in New Orleans, witnessed jealous treachery on every hand. This had taught me that enemies of my race were numerous, while, it was probable, not more than a dozen fellow-countrymen were then in New Orleans. They would prove powerless were I to become involved in any quarrel. Extreme caution under such conditions became a paramount duty, and it can scarcely be wondered at that I hesitated to trust the black, continuing to study the real purpose of his mysterious message. Yet the rare good-humor and simple interest of his face tended to reassure me. A lady, he said—well, surely no great harm would result from such an interview; and if, as was probable, it should prove a mere case of mistaken identity, a correction could easily follow, and I should then be free to go my way. On the other hand, if some friend really needed me, a question of duty was involved, which—God helping—I was never one to shun; for who could know in how brief a space I might also be asking assistance of some countryman. This mysterious stranger, this Madame de Noyan of whom I had never heard, knew my name—possibly had learned it from another, some wandering Englishman, perchance, whom she would aid in trouble, some old-time friend in danger, who, afraid to reveal himself, now appealed through her instrumentality for help in a strange land. Deciding to brave the doubt and solve the mystery by action, I flung the long rifle across my shoulder and stood erect.

"All right, boy, lead on," I said shortly. "I intend to learn what is behind this, and who it is that sends for me in New Orleans."

Far from satisfied with the situation, yet determined now to probe the mystery to the bottom, I silently followed the black, attentive to his slightest movement. It was a brief walk down one of the narrow streets leading directly back from the river front, so that within less than five minutes I was being silently shown into the small reception room of a tasty cottage, whose picturesque front was half concealed by a brilliant mass of trailing vines. The heavy shades being closely drawn at the windows, the interior was in such gloom that for the moment after my entrance from the outside glare I was unable to distinguish one object from another. Then slowly my eyes adjusted themselves to the change, and, taking one uncertain step forward, I came suddenly face to face with a Capuchin priest appearing almost ghastly with his long, pale, ascetic countenance, and ghostly gray robe sweeping to the floor.

Startled by this unexpected apparition, and experiencing an American borderer's dislike and distrust for his class, I made a hasty move back toward where, with unusual carelessness, I had deposited my rifle against the wall. Yet as I placed hand upon it I had sufficiently recovered to laugh silently at my fears.

"Thou hast responded with much promptitude, my son," the priest said in gentle voice, speaking the purest of French, and apparently not choosing to notice my momentary confusion. "It is indeed an excellent trait—one long inculcated by our Order."

"And one not unknown to mine—free rangers of the woods, sir priest," I replied coldly, resolving not to be outdone in bluntness of speech. "I suppose you are the 'lady' desiring speech with me; I note you come dressed in character. And now I am here, what may the message be?"

There was neither smile nor resentment visible on his pale face, although he slightly uplifted one slender hand as if in silent rebuke of my rude words.

"Nay, nay, my son," he said gravely. "Be not over-hasty in speech. It is indeed a serious matter which doth require thy presence in this house, and the question of life or death for a human being can never be fit subject for jesting. She who despatched the messenger will be here directly to make clear her need."

"In truth it was a woman, then?"

"Yes, a woman, and—ah! she cometh now."

Even as he gave utterance to the words, I turned, attracted by the soft rustle of a silken skirt at my very side, stole one quick, startled glance into a young, sweet face, lightened by dark, dreamy eyes, and within the instant was warmly clasping two outstretched hands, totally oblivious of all else save her.

"Eloise!" I exclaimed in astonishment. "Eloise—Mademoiselle Lafrénière—can this indeed be you? Have you sent for me?"

It seemed for that one moment as if the world held but the two of us, and there was a glad confidence in her brimming eyes quickly dissipating all mists of the past. Yet only for that one weak, thoughtless instant did she yield to what appeared real joy at my presence.

"Yes, dear friend, it is Eloise," she answered, gazing anxiously into my face, and clinging to my strong hands as though fearful lest I might tear them away when she spoke those hard words which must follow. "Yet surely you know, Geoffrey Benteen, that I am Mademoiselle Lafrénière no longer?"

It seemed to me my very heart stopped beating, so intense was the pain which overswept it. Yet I held to the soft hands, for there was such a pitiful look of suffering upon her upturned face as to steady me.

"No, I knew it not," I answered brokenly. "I—I have been buried in the forest all these years since we parted, where few rumors of the town have reached me. But let that pass; it—it is easy to see you are now in great sorrow. Was it because of this—in search of help, in need, perchance—that you have sent for me?"

She bowed her head; a tear fell upon my broad hand and glistened there.

"Yes, Geoffrey."

The words were scarcely more than a whisper; then the low voice seemed to strengthen with return of confidence, her dark eyes anxiously searching my face.

"I sent for you, Geoffrey, because of deep trouble; because I am left alone, without friends, saving only the père. I know well your faithfulness. In spite of the wrong, the misunderstanding between us—and for it I take all the blame—I have ever trusted in your word, your honor; and now, when I can turn nowhere else for earthly aid, the good God has guided you back to New Orleans. Geoffrey Benteen, do not gaze at me so! It breaks my heart to see that look in your eyes; but, my friend, my dearest friend, do you still recall what you said to me so bravely the night you went away?"

Did I remember! God knew I did; ay! each word of that interview had been burned into my life, had been repeated again and again in the silence of my heart amid the loneliness of the woods; nothing in all those years had for one moment obliterated her face or speech from memory.

"I remember, Eloise," I answered more calmly. "The words you mean were: 'If ever you have need of one on whom you may rely for any service, however desperate (and in New Orleans such necessity might arise at any moment), one who would gladly yield his very life to serve you, then, wherever he may be, send for Geoffrey Benteen.' My poor girl, has that moment come?"

The brown head drooped until it rested in unconsciousness against my arm, while I could feel the sobs which shook her form and choked her utterance.

"It has come," she whispered at last; "I am trusting in your promise."

"Nor in vain; my life is at your command."

She stopped my passionate utterance with quick, impulsive gesture.

"No! pledge not yourself again until you hear my words, and ponder them," she cried, with return to that imperiousness of manner I had loved so well. "This is no ordinary matter. It will try your utmost love; perchance place your life in such deadly peril as you never faced before. For I must ask of you what no one else would ever venture to require—nor can I hold out before you the slightest reward, save my deepest gratitude."

I gazed fixedly at her flushed face, scarcely comprehending the strange words she spoke.

"What may all this be that you require—this sacrifice so vast that you doubt me? Surely I have never stood a coward, a dastard in your sight?"

She stood erect, facing me, proudly confident in her power, with tears still clinging to her long lashes.

"No! you wrong me uttering such a thought. I doubt you not, although I might well doubt any other walking this earth. But listen, and you can no longer question my words; this which I dare ask of you—because I trust you—is to save my husband."

"Your husband?" The very utterance of the word choked me. "Your husband? Save him from what? Where is he?"

"A prisoner to the Spaniards; condemned to die to-morrow at sunrise."

"His name?"

"Chevalier Charles de Noyan."

"Where confined?"

"Upon the flag-ship in the river."

I turned away and stood with my back to them both. I could no longer bear to gaze upon her agonized face uplifted in such eager pleading, such confiding trust; that one sweet face I loved as nothing else on earth.

Save her husband! For the moment it seemed as if a thousand emotions swayed me. What might it not mean if this man should die? His living could only add infinitely to my pain; his death might insure my happiness—at least he alone, as far as I knew, stood in the way. "To die to-morrow!" The very words sounded sweet in my ears, and it would be such an easy thing for me to promise her, to appear to do my very best—and fail. "To die to-morrow!" The perspiration gathered in drops upon my forehead as I wavered an instant to the tempting thought. Then I shook the foul temptation from me. Merciful God! could I dream of being such a dastard? Why not attempt what she asked? After all, what was left for me in life, except to give her happiness?

The sound of a faint sob reached me, and wheeling instantly I stood at her side.

"Madame de Noyan," I said with forced calmness, surprising myself, "I will redeem my pledge, and either save your husband, or meet my fate at his side."

Before I could prevent her action she had flung herself at my feet, and was kissing my hand.

"God bless you, Geoffrey Benteen! God bless you!" she sobbed impulsively; and then from out the dense shadows of the farther wall, solemnly as though he stood at altar service, the watchful Capuchin said:

"Amen!"

Any call to action, of either hazard or pleasure, steadies my nerves. To realize necessity for doing renders me a new man, clear of brain, quick of decision. Possibly this comes from that active life I have always led in the open. Be the cause what it may, I was the first to recover speech.

"I hope to show myself worthy your trust, Madame," I said somewhat stiffly, for it hurt to realize that this emotion arose from her husband's peril. "At best I am only an adventurer, and rely upon those means with which life upon the border renders me familiar. Such may prove useless where I have soldiers of skill to deal with. However, we have need of these minutes flying past so rapidly; they might be put to better use than tears, or words of gratitude."

She looked upward at me with wet eyes.

"You are right; I am a child, it seems. Tell me your desire, and I will endeavor to act the woman."

"First, I must comprehend more clearly the nature of the work before me. The Chevalier de Noyan is already under sentence of death; the hour of execution to-morrow at sunrise?"

She bent her head in quiet acquiescence, her anxious eyes never leaving my face.

"It is now already approaching noon, leaving us barely eighteen hours in which to effect his rescue. Faith! 't is short space for action."

I glanced uneasily aside at the silently observant priest, now standing, a slender gray figure, close beside the door. He was not of an Order I greatly loved.

"You need have no fear," she exclaimed, hastily interpreting my thought. "Father Petreni can be fully trusted. He is more than my religious confessor; he has been my friend from childhood."

"Yes, Monsieur," he interposed sadly, yet with a grave smile lighting his thin white face. "I shall be able to accomplish little in your aid, for my trade is not that of arms, yet, within my physical limitations, I am freely at your service."

"That is well," I responded heartily, words and tone yielding me fresh confidence in the man. "This is likely to prove a night when comrades will need to know each other. Now a few questions, after which I will look over the ground before attempting to outline any plan of action. You say, Madame, that your—Chevalier de Noyan is a prisoner on the fleet in the river. Upon which ship is he confined?"

"The 'Santa Maria.'"

"The 'Santa Maria'?—if memory serve, the largest of them all?"

"Yes! the flag-ship."

"She lies, as I remember, for I stood on the levee two hours ago watching the strange spectacle, close in toward the shore, beside the old sugar warehouse of Bomanceaux et fils."

"You are correct," returned the Capuchin soberly, the lady hesitating. "The ship swingeth by her cable scarce thirty feet from the bank."

"That, at least, has sound of good fortune," I thought, revolving rapidly a sudden inspiration from his answer, "yet it will prove a desperate trick to try."

Then I spoke aloud once more.

"She appeared a veritable monster of the sea to my backwoods eyes; enough to pluck the heart out of a man. Has either of you stepped aboard her?"

The priest shook his shaven head despondently.

"Nay; never any Frenchman, except as prisoner in shackles, has found foothold upon that deck since O'Reilly came. It is reported no negro boatmen are permitted to approach her side with cargoes of fruit and vegetables, so closely is she guarded against all chances of treachery."

"Faith! it must be an important crime to bring such extremity of vigilance. With what is De Noyan charged?"

"He, with others, is held for treason against the King of Spain."

"There are more than one, then?"

"Five." He lowered his voice almost to a whisper. "Madame de Noyan's father is among them."

"Lafrénière?" I uttered the name in astonishment. "Then why am I not asked to assist him?"

The thoughtless exclamation cut her deeply with its seeming implication of neglect, yet the words she strove to speak failed to come. The priest rebuked me gravely:

"Thou doest great injustice by such inconsiderate speech, my son. There are hearts loyal to France in this province, who would count living a crime if it were won at the cost of Lafrénière. He hath been already offered liberty, yet deliberately chooseth to remain and meet his fate. Holy Mother! we can do no more."

I bent, taking her moist hands gently between my own.

"I beg you pardon me, Madame; I am not yet wholly myself, and intended no such offence as my hasty words would seem to imply. One's manners do not improve with long dwelling among savages."

She met my stumbling apology with a radiant smile.

"I know your heart too well to misjudge. Yet it hurt me to feel you could deem me thoughtless toward my father."

"You have seen him since his arrest?"

"Once only—at the Captain-General's office, before they were condemned and taken aboard the flag-ship."

"But the prisoners are Catholics; surely they are permitted the offices of the Church at such a time?"

A hard look swept across the Capuchin's pale, ascetic face.

"Oh, ay! I had quite forgotten," he explained bitterly. "They enjoy the ministrations of Father Cassati, of our Order, as representative of Holy Church."

"Pouf!" I muttered gloomily. "It is bad to have the guard-lines drawn so closely. Besides, I know little about the way of ships; how they are arranged within, or even along the open decks. We meet them not in the backwoods, so this is an adventure little to my taste. It would hardly be prudent, even could I obtain safe footing there, to attempt following a trail in the dark when I knew not where it led. I must either see the path I am to travel by good daylight, or else procure a guide. This Father Cassati might answer. Is he one to trust?"

The priest turned his head away with a quick gesture of indignant dissent.

"Nay!" he exclaimed emphatically. "He must never be approached upon such a matter. He can be sweet enough with all men to their faces; the words of his mouth are as honey; yet he would be true to none. It is not according to the canons of our Order for me thus to speak, yet I only give utterance to truth as I know it in the sight of God. Not even the Spaniards themselves have faith in him. He has not been permitted to set foot upon shore since first he went aboard."

"And you have no plan, no suggestion to offer for my guidance?"

"Mon Dieu, no!" he cried dramatically. "I cannot think the first thing."

"And you, Madame?"

She was kneeling close beside a large chair, her fine dark eyes eagerly searching my face.

"It rests wholly with you," she said solemnly, "and God."

Twice, three times, I paced slowly across the floor in anxious reflection; each time, as I turned, I gazed again into her trustful, appealing eyes. It was love calling to me in silent language far more effective than speech; at last, I paused and faced her.

"Madame de Noyan," I said deliberately, my voice seeming to falter with the intensity of my feelings, "I beg you do not expect too much from me. Your appeal has been made to a simple frontiersman, unskilled in war except with savages, and it is hardly probable I shall be able to outwit the trained guardsmen of Spain. Yet this I will say: I have determined to venture all at your desire. As I possess small skill or knowledge to aid me, I shall put audacity to the front, permitting sheer daring either to succeed or fail. But it would be wrong, Madame, for me to encourage you with false expectation. I deem it best to be perfectly frank, and I do not clearly see how this rescue is to be accomplished. I can form no definite plan of action; all I even hope for is, that the good God will open up a path, showing me how such desperate purpose may be accomplished. If this prove true—and I beg you pray fervently to that end—you may trust me to accept the guidance, let the personal danger be what it may. But I cannot plan, cannot promise—I can only go forward blindly, seeking some opening not now apparent. This alone I know, to remain here in conversation is useless. I must discover means by which I may reach the 'Santa Maria' and penetrate below her deck if possible. That is my first object, and it alone presents a problem sufficient to tax my poor wits to the uttermost. So all I dare say now, Madame, is, that I will use my utmost endeavor to save your hus—the Chevalier de Noyan. I request you both remain here—it would be well in prayer—ready to receive, and obey at once, any message I may need to send. If possible I will visit you again in person before nightfall, but in any case, and whatever happens, try to believe that I am doing all I can with such brains as I possess, and that I count my own life nothing in your service."

However they may sound now, there was no spirit of boasting in these words. Conceit is not of my nature, and, indeed, at that time I had small enough faith in myself. I merely sought to encourage the poor girl with what little hope I possessed, and knew she read the truth behind those utterances which sounded so brave. Even as I finished she arose to her feet, standing erect before me, looking a very queen.

"Never will I doubt that, Geoffrey Benteen," she declared impulsively. "I have seen you in danger, and never forgotten it. If it is any encouragement to hear it spoken from my lips, know, even as you go forth from here, that never did woman trust man as I trust you."

The hot blood surged into my face with a madness I retained barely sufficient strength to conquer.

"I—I accept your words in the same spirit with which they are offered," I stammered, hardly aware of what I said. "They are of greatest worth to me."

I bowed low above the white hand resting so confidingly within mine, anxious to escape from the room before my love gave utterance to some foolish speech. Yet even as I turned hastily toward the door, I paused with a final question.

"The negro who guided me here, Madame; is he one in whom I may repose confidence?"

"In all things," she answered gravely. "He has been with the De Noyan family from a child, and is devoted to his master."

"Then I take him with me for use should I chance to require a messenger."

With a swift backward glance into her earnest dark eyes, an indulgence I could not deny myself, I bowed my way forth from the room, and discovering Alphonse upon the porch, where he evidently felt himself on guard, and bidding him it was the will of his mistress that he follow, I flung my rifle across my shoulder, and strode straight ahead until I came out upon the river bank. Turning to the right I worked my way rapidly up the stream, passing numerous groups of lounging soldiers, who made little effort to bar my passage, beyond some idle chaffing, until I found myself opposite the anchorage of the Spanish fleet.

In the character of an unsophisticated frontiersman, I felt no danger in joining others of my class, lounging listlessly about in small groups discussing the situation, and gazing with awe upon those strange ships of war, swinging by their cables in the broad stream. It was a motley crew among whom I foregathered, one to awaken interest at any other time—French voyageurs from the far-off Illinois country, as barbarian in dress and actions as the native denizens of those northern plains, commingling freely with Creole hunters freshly arrived from the bayous of the swamp lands; sunburnt fishermen from the sandy beaches of Barataria, long-haired flatboat-men, their northern skin faintly visible through the tan and dirt acquired in the long voyage from the upper Ohio; here and there some stolid Indian brave, resplendent in paint and feathers, and not a few drunken soldiers temporarily escaped from their commands. Yet I gave these little thought, except to push my way through them to where I could obtain unobstructed view of the great ships.

The largest of these, a grim monster to my eyes, with bulging sides towering high above the water, and masts uplifting heavy spars far into the blue sky, rendered especially formidable by gaping muzzles of numerous black cannon visible through her open ports, floated just beyond the landing. I measured carefully the apparent distance between the flat roof of the sugar warehouse, against the corner of which I leaned in seeming listlessness, and the lower yards of her forward mast—it was no farther than I had often cast a riata, yet it would be a skilful toss on a black night.

However, I received small comfort from the thought, for there was that about this great gloomy war-ship—frigate those about me called her—which awed and depressed my spirits; all appeared so ponderously sullen, so massive with concealed power, so mysteriously silent. My eyes, searching for each visible object, detected scarcely a stir of life aboard, except as some head would arise for an instant above the rail, or my glance fell upon the motionless figure of a sentry, standing at the top of the narrow steps leading downward to the water, a huge burly fellow, whose side-arms glistened ominously in the sun. These were the sole signs of human presence; yet, from snatches of conversation, I learned that hidden away in the heart of that black floating monster of wood and iron, were nearly four hundred men, and the mere knowledge made the sombre silence more impressive than ever.

Except for gossiping spectators lining the shore, nothing living appeared about the entire scene, if I except a dozen or more small boats, propelled by lusty black oarsmen, deeply laden with produce, busily plying back and forth between various vessels, seeking market for their wares. Even these, as the priest told me, had apparently been warned away from the flag-ship, as I observed how carefully they avoided any approach to her boarding-ladder. The longer I remained, the more thoroughly hopeless appeared any prospect of success. Nor could I conjure up a practical—nay! even possible—method of placing so much as a foot on board the "Santa Maria." Surely never was prison-ship guarded with more jealous care, and never did man face more hopeless quest than this confronting me. The longer I gazed upon that grim, black, sullen mass of wood and iron—that floating fortress of despotic Spanish power—the more desperate appeared my mission; the darker grew every possibility of plucking a victim from out that monster's tightly closed jaws. Yet I was not one to forego an enterprise lightly because of difficulty or danger, so with dogged persistency I clung to the water front, knowing nowhere else to go, and blindly trusting that some happening might open to me a door of opportunity.

It frequently seems that when a man once comes, in a just cause, to such mind as this, when he trusts God rather than himself, there is a divinity which aids him. Surely it was well I waited in patience, for suddenly another produce boat, evidently new to the trade, deeply laden with fruit and roots, bore down the river, the two negroes at the oars pointing its blunt nose directly toward the flag-ship, attracted no doubt by its superior size. Instantly noting their course I awaited their reception with interest, an interest intensified by a drawling English voice from amid the crowd about me, saying:

"I reckon thar'll be some dead niggers in thet thar bumboat if they don't sheer off almighty soon."

Scarcely were these prophetic words uttered, when the soldier statue at the head of the boarding-stairs swung his musket forward into position, and hailed in emphatic Spanish, a language which, thanks to my mother, I knew fairly well. There followed a moment of angry controversy, during which the startled negroes rested upon their oars, while the enraged guard threatened to fire if they drifted a yard closer. In the midst of this hubbub a head suddenly popped up above the rail. Then a tall, ungainly figure, clad in a faded, ill-fitting uniform, raised itself slowly, leaning far out over the side, a pair of weak eyes, shadowed by colored glasses, gazing down inquiringly into the small boat.

"Vat ees it you say you have zare?" he asked in an attempt at French, which I may only pretend to reproduce in English. "Vat ees ze cargo of ze leetle boat?"

Instantly the two hucksters gave voice, fairly running over each other in their confused jargon, during which I managed to distinguish native names for potatoes, yams, sweet corn, peaches, apples, and I know not what else.

The Spaniard perched high on the rail waved his long arms in unmitigated disgust.

"Caramba!" he cried the moment he could make his voice distinguished above the uproar. "I vant none of zos zings; Saint Cristoval, non! non! Ze Capitaine he tole me get him some of ze olif—haf you no olif in ze leetle boat?"

The darkies shook their heads, instantly starting in again to call their wares, but the fellow on the rail waved them back.

"Zen ve don't vant you here!" he cried shrilly. "Go vay dam quick, or else ze soldier shoot." As if in obedience to an order the stolid guard brought his weapon menacingly to the shoulder.

How the episode terminated I did not remain to learn. At that moment I only clearly comprehended this—I had a way opened, an exceedingly slight one to be sure, of doubtful utility, yet still a way, which might lead me into the guarded mystery of that ship. The time for action had arrived, and that was like a draught of wine to me. Eagerly I slipped back through the increasing crowd of gaping countrymen, to where the negro had found a spot of comfort in the sun.

"Alphonse!" I called, careful to modulate my voice. "Wake up, you black sleepy-head! Ay! I have you at last in the world again. Now stop blinking, and pay heed to what I say. Do you chance to know where, for love, money, or any consideration, you could lay hands on olives in this town?"

The fellow, scarcely awake, rolled up the whites of his eyes for a moment, and scratched his woolly pate, as if seeking vainly to conjure up some long-neglected memory. Then his naturally good-humored countenance relaxed into a broad grin.

"Fo' de Lord, yas sah! I'se your man dis time suah 'nough. Dat fat ol' Dutchman, down by de Tehoupitoulas Gate, suah as you're born had a whole barrel ob dem yesterday. I done disremember fer de minute, boss, jist whar I done saw dem olibs, but I reckon as how de money 'd fotch 'em all right."

I drew forth a handful of French coins.

"Then run for it, lad!" I exclaimed in some excitement. "Your master's life hangs upon your speed—hold, wait! do you remember that old tumble-down shed we passed on our way here; the one which had once been a farrier's shop?"

The negro nodded, his eyes filled with awakened interest.

"Good; then first of all bring me a suit of the worst looking old clothes you can scare up in the negro quarters of this town. Leave them there. Then go directly to this Dutchman's, buy every olive he has for sale at any price, load them into a boat—a common huckster's boat, mind you, and remain there with them until I come. Do you understand all that?"

"Yas, Massa; I reckon as how I kin do dat all right 'nough." The fellow grinned, every white ivory showing between his thick red lips.

"Don't stop to speak to any one, black or white. Now trot along lively, and may the Lord have mercy on you if you fail me, for I pledge you I shall have none."

I watched him disappear up the street in a sort of swinging dog-trot, took one more glance backward at the huge war-ship, now swinging by her cable silent and mysterious as ever, and turned away from the river front, my brain teeming with a scheme upon the final issue of which hung life or death.

I had seldom assumed disguise, except when wearing Indian garb upon the war-trail. Yet in boyhood I had occasionally masqueraded as a negro so successfully as to deceive even my own family. With this in mind the resolve was taken that in no other guise than that of a foolish, huckstering darky could I hope to attain the guarded deck of that Spanish frigate. This offered only the barest chance of success, yet such chances had previously served me well, and must be trusted now. Opportunity frequently opens to the push of a venturesome shoulder.

Once determined upon this I set to work, perfecting each detail which might aid in the hazardous undertaking. Much was to be accomplished, and consequently it was late in the afternoon before the two of us, myself as much a negro to outward appearance as my sable companion, floated anxiously down the broad river in a battered old scow heaped high with every variety of country produce obtainable. Drifting with the current, I kept the blunt nose pointed directly toward the bulging side of the "Santa Maria," yet without venturing to glance in that direction, until a sharp challenge of the vigilant sentinel warned us to sheer off.

Slowly shipping the heavy steering oar, finding it difficult even in that moment of suspense to suppress a smile at the expression of terror on Alphonse's black face, I stood up, awed by the solemn massiveness of the vast bulk towering above me, now barely thirty feet away. For the first time I realized fully the desperation of my task, and my heart sank. But the gesticulations of the wrathful guard could no longer be ignored, and, smothering an exclamation of disgust at my momentary weakness, I nerved myself for the play.

"Caramba!" the fellow shouted roughly in his native tongue. "Stop there, you lazy niggers; don't let that boat drift any closer. Come, sheer off, or, by all the saints, I 'll blow a hole clear through the black hide of one of you!"

"Hold her back, boy!" I muttered hurriedly to the willing slave. "That soldier means to shoot."

Then I held up a handful of our choicest fruit into view.

"I have got plenty vegetables, an' lot fruit fer sell," I shouted eagerly in negro French, putting all the volume possible into my voice, hopeful my words might penetrate the hidden deck above. "Plenty 'tatoes, peaches, olibs—eberyting fer de oppercers."

"Don't want them—pull away, and be lively about it."

It was a moment of despair, every hope suspended in the balance; my heart beating like a trip-hammer with suspense. The thoroughly enraged guard lifted his gun to the shoulder; there was threat in his eyes, yet I ventured a desperate chance of one more word.

"I got de only olibs on dis ribber."

"Bastenade!" yelled the infuriated fellow. "I 'll give you a shot to pay for your insolence."

Even as he spoke, fumbling the lock of his gun, that same head observed before suddenly popped over the high rail like Punch at a pantomime.

"Vat zat you say, nigger?" its owner cried doubtingly. "Vas it ze olif you haf zare in ze leetle boat?"

I eagerly held up into view a choice handful of green fruit, my eyes hopeful.

"Oui, Señor Oppercer—fresh olibs; same as ob your lan'."

The Spaniard was standing upright on the rail by this time, clinging fast to a rope dangling from above, leaning far over, no slight interest depicted upon his pinched, sallow countenance.

"It's all right, sentry," he said sharply to the soldier, who lowered his gun with a scowl indicating his real desire. My newly found friend lifted his squeaking voice again in unfamiliar speech.

"Bring ze leetle boat along ze side of ze sheep, you black fellar, an' come up here wiz ze olif fer ze Capitaine."

"Scull in close against those steps, Alphonse," I muttered, overjoyed at this rare stroke of good fortune. "Then pull out a few strokes; but stay alongside until I come back. Don't let any one get aboard, and keep a quiet tongue yourself."

The whites of his eyes alone answered me, he being too badly frightened for speech. The situation was one to grate upon any nerves unaccustomed to danger, yet, trusting the long training of the slave would hold him obedient, I turned away, and, in another moment, had scrambled up the rope ladder, plunging awkwardly over the high rail on to the hitherto concealed deck. My pulses throbbed with excitement over the desperate game fronting me, yet, with a coolness surprising to myself, I lost at that instant every sensation of personal fear, in determination to act thoroughly my assumed character. More lives than one hung in the balance, and, with tightly clenched teeth, I swore to prove equal to the venture. The very touch of those deck planks to my bare feet put new recklessness into my blood, causing me to marvel at the perfection of my own fool play.

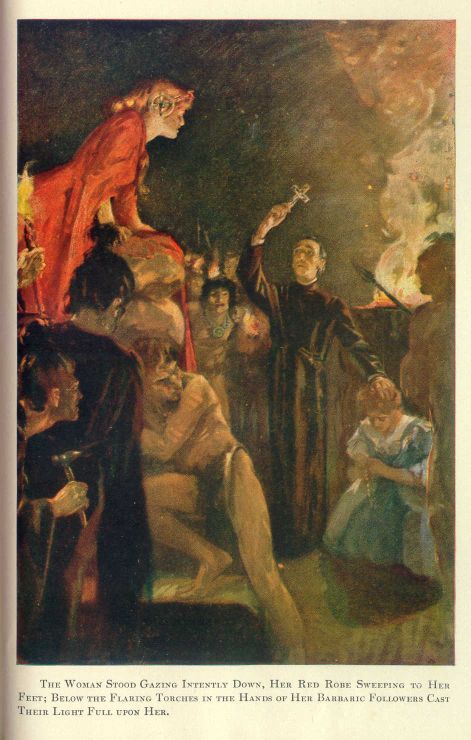

The gaunt Spaniard commanding my presence stood waiting, hardly more than five paces from where I landed, yet so intense became my immediate interest in the strange scene—an interest partly real, but largely simulated for the occasion—that he contented himself watching my confused antics with much apparent amusement, and without addressing me. Even to this hour that scene lies distinct before my eyes. Possessed I skill with pencil I could sketch each small detail from the retina of memory—the solitary sentinel beside the rail, his well-worn uniform of blue and white dingy in the sun; another farther forward, where a great opening yawned; with yet a third, standing rigid before a closed door of the after cabin. An officer, his coat richly decorated with gold braid, wearing epaulets, and having a short sword dangling at his side, paced back and forth across the top of a little house near the stern. I heard him utter some command to a sailor near the wheel, but he never so much as glanced toward me. Perhaps thirty or more seamen, bronzed of face, and oddly bedecked as to hair, lounged idly amid the shadows opposite, while, more closely at hand, that gaunt, cadaverous Spaniard, at whose invitation I was present, leaned against a big gun, puffing nonchalantly at a cigarette, held between lean, saffron-colored fingers. The deck was white as the snows of a northern Winter, while the brass work along the railings and about the cannon glittered brilliantly in the sunshine. There was a gaudy yellow-and-white striped canopy stretched above a portion of the deck aft; the huge masts seemed to pierce into the blue of the skies; while on every side were ranged grim guns of brass and iron.

My role was that of an ignorant, green, half-frightened darky, and I presume I both appeared and acted the natural-born idiot, if I might judge from the expression upon the Spaniard's face, and the broad grin lighting up the fierce countenance of the sentry at the gangway. Yet back of this mask there was grim determination and fixed purpose, so that no article of furniture was along that broad deck which I did not mentally photograph, so as to know its whereabouts if ever I chanced that way again. Ay! even to a little cuddy door beside the cookhouse, apparently opening directly into the mysterious regions below, and a great chest lashed hard against the rail, within which I distinguished the bright colors of numerous flags. I noticed also the odd manner in which queer rope ladders led up from either side of the broad deck to the vast spars high above, rising tier on tier until my head grew dazed with gazing at them.

"Vel, Sambo, my black fellow," grinned the officer, whose eyes were still lazily following my erratic movements as I peered innocently into the muzzle of a brass carronade in apparent hope of discovering the ball, "zis vus ze first time you vus ever on ze war-sheep, I sink likely. How you like stop here, hey, an' fight wis dos sings?" And he rested his yellow hand caressingly upon the breech of the gun.

I shook my head energetically, rendering as prominent as possible the whites of my eyes, at which he grinned wider than ever.

"No, sah, Mister Oppercer Man; you don't git dis hyer nigger into no fought, sah," I protested with vehemence. "I done fought wid de Injuns onct, sah, an' I done don't want no mo'."

"Veil, you not vorry, boy; you voud be no good on ze war-sheep. But now you come wis me to ze Capitaine—bring ze olif."

Bearing a tempting sample of the Spaniard's favorite fruit tightly clutched in my black hand, and pulling my battered straw hat lower in concealment of my telltale hair, I made awkward attempt to shuffle along behind him, as he carelessly advanced toward the after part of the vessel. But I loitered along our passage to examine so many objects of curiosity, asking such a multitude of extremely absurd questions, that we consumed considerable time in traversing even the comparatively short distance to where the rigid sentinel fronted us before the cabin door. My queries were simple enough to have birth in the brain of a fool, yet my guide was of rare good humor, and evidently so amused at my ignorant curiosity that his patience withstood the strain. On my part none were blindly asked, but were intended to open a way toward others of the utmost importance. My sole purpose at that moment was to lull suspicion to rest; when that had been accomplished, then I might confidently hope to pump my trustful victim of such information as I imperatively required. The ignorant questions of an imbecile will oftentimes be frankly responded to, where a wise man might ask in vain, and my first play was to establish my character as a fool. That I had succeeded was already evident.

The statuesque guard before the cabin brought his musket up at our approach with so smart a snap as to startle me into a moment's apparent terror. To the officer's request that we be admitted to the presence of the Captain, he responded briefly that that officer had gone forward half an hour before. My guide glanced about as if uncertain where he had better turn in search.

"Did he go down the hatch?" he queried shortly.

"I know not, Señor Gonzales," was the respectful reply. "But I believe he may be with the prisoners' guard below."

The officer promptly started forward, and, awaiting no formal invitation, I shambled briskly after, keeping as close as possible to his heels. Could I gain a brief glimpse below the deck it would be worth more to me than any amount of blind questioning, and my heart thumped painfully in remembrance of what hung upon his movements. With a single sharp word to the sentry at the hatch he swung himself carelessly over the edge, mysteriously disappearing into the gloom beneath. That was no time for hesitancy, and I was already preparing to do likewise, when the guard, a surly-looking brute, promptly inserted the point of his bayonet into my ragged garment, accompanying this kindly act with a stern order to remain where I was.

"An' what fo' yo' do dat, Señor Sojer?" I cried, in unaffected anguish, rubbing the injured part tenderly, yet speaking loud so that my words should be distinctly audible below. "Dat oppercer man he done tol' me to foller him to de Captain. What fo' yo' stop me wid dat toastin' fork?"

"It's all right, Manuel," sung out a voice in Spanish from the lower darkness. "Let the fool nigger come down."

The thoroughly disgusted soldier muttered something about his orders, that his lieutenant had not ever authorized him to pass fools. Overlooking this personal allusion, and fearing more serious opposition from some one higher in authority, I took advantage of his momentary doubt, promptly swung my legs over the edge of the hatch opening, groped blindly about with my bare feet until they struck the rungs of a narrow ladder, and went scrambling down into the semi-darkness of between-decks, managing awkwardly to miss my final footing, thus flopping in a ragged heap at the bottom.

"Holy Mother! you make more noise zan a sheep in action," grumbled the startled officer, as I landed at his feet. "Vat for you come down ze ladder zat vay?"

Rubbing my numerous bruises energetically, I contented myself with staring up at him as if completely dazed by my fall. Reading in his amused countenance no symptom of awakening suspicion I ventured a quick glance at my new surroundings. We were in what appeared a large unfurnished room, with doors of all sizes opening in every direction, while I could perceive a narrow entry, or passageway, extending toward the after part of the vessel. The roof, formed of the upper deck, was low, upheld by immense timbers, and the apartment, nearly square, was dimly flooded by the sparse light sifting down through the single hatch-opening above, so that, in spite of its large dimensions, it had a cramped and stuffy appearance. The vast butt of the mainmast arose directly in front of me, and, upon a narrow bench surrounding it, a dozen soldiers were lounging, while near the entrance to the passageway, scarcely more than a shadow in that dimness, stood a sentry, stiff and erect, with musket at his shoulder. They were mostly slightly built, dark-featured men, attired in blue and white uniforms, the worse for wear, and were all laughing at my crazy entrance. No doubt my coming afforded some relief to their tiresome, dull routine. While lying there, apparently breathless from my fall, my brains effectively muddled, a young officer advanced hastily from out the gloom to inquire into so unusual an uproar.

"What is all this noise about?" he questioned sharply, striding toward us. "Ah, Gonzales; whom have you here? Another bird to add to our fine collection?"

"If so, it must be a rare blackbird, Señor Francisco," returned my friend, vainly endeavoring to recover his customary gravity. "By Saint Cristobal! I have not laughed so heartily for a year past as at this poor black fool. Faith, I sought to enlist him in the service of His Most Christian Majesty, yet his method of coming down a companion ladder convinced me he sadly lacks the necessary qualifications for a sailor. Hast seen aught of the Captain here below?"

"Ay, comrade, thou wilt find him aft. He hath just had speech once more with the chief rebel, the graybeard they call Lafrénière, and was in raging temper when last we met. Caramba! he even called me an ass, for no more serious fault, forsooth, than that I made the round of my guard unattended. Hath your darky news for him?"

"Nay; the fellow possesseth not sufficient sense to be a messenger, except it may be a message for his stomach to make his humor better," was the reply. "Come, trot along now, boy, and mind where you put down those big feet in the passage."

I struggled upright in response to his order, assisted by the sharp tap of a boot accompanying it, tripped over a gun barrel one of the guard facetiously inserted between my legs, and went down once more, uttering such howl of terror as could be only partially drowned beneath the uproarious laughter of my merry tormentors. It developed into a gantlet, yet I ran the line with little damage, and, after much ducking and pleading, managed to regain my position close to the heels of Señor Gonzales before he turned into the passageway, which, as I now perceived, was dimly illumined by means of a single lantern, hung to a blackened upper beam.

"Well, good luck to both of you," called out the young officer of the guard laughingly as we disappeared. "Yet I 'd hate to have the steering of such a crazy craft as follows in your wake, Gonzales, and I warn you again the Señor Captain will be found in beastly humor."

"I fear nothing," returned my guide, his lean yellow face turned backward over his shoulder. "I have what will bring him greater happiness than a decoration from the King."

Shambling awkwardly forward, simulating all the uncouthness possible, I retained my wits sufficiently to note our surroundings—the long, narrow passage, scarcely exceeding a yard in width, with numerous doors opening on either side. Several of these stood ajar, and I perceived berths within, marking them as sleeping apartments, although one upon the right was evidently being utilized as a linen closet, while yet another, just beyond, and considerably larger, seemed littered with a medley of boxes, barrels, and great bags. This apartment appeared so much lighter than those others, even a stray ray of sunshine pouring directly down into it from above, that I instinctively connected it in my mind with the cook-house on the upper deck, and the open cuddy door I had chanced to notice.

As we approached the farther end this passage suddenly widened into a half circle, sufficiently extended to accommodate the huge butt of the mizzenmast, which was completely surrounded by an arm-rack crowded with short-swords, together with all manner of small arms. A grimly silent guard stood at either side, and I perceived the dark shadow of a third still farther beyond, while the half-dozen cabins close at hand had their doors tightly closed, and fastened with iron bars.

Instinctively I felt that here were confined those French prisoners, the knowledge of whose exact whereabouts I sought amid such surroundings of personal peril, and my heart bounded from sudden excitement. In simulated awkwardness, I unfortunately overdid my part. Shuffling forward, more eager than ever to keep at the heels of my protector, yet with eyes wandering in search of any opening, my bare feet struck against a projecting ring-bolt in the deck, and over I went, striving vainly to regain my balance. Before that human statue on guard could even lower his gun to repel boarders, my head struck him soundly in the stomach, sending him crashing back against one of those tightly closed doors. Tangled up with the surprised soldier, who promptly clinched his unexpected antagonist, and, with shocking profanity, strove to throttle me, I yet chanced to take note of the number "18" painted upon the white wood just above us. Then the door itself was hurled hastily open, and with fierce exclamation of rage a gray-hooded Capuchin monk bounded forth like a rubber ball, and instantly began kicking vigorously right and left at our struggling figures. It gives me pleasure to record that the Spaniard, being on top, received by far the worst of it, yet I might also bear testimony to the vigor of the priest's legs, while we shared equally in the volubility of his tongue.

"Sacre!" he screamed in French, punctuating each sentence with a fresh blow. "Get away from here, you drunken, quarrelling brutes! Has it come to this, that a respectable priest of Holy Church may not hold private converse with the condemned without a brawl at the very door? Mother of God! what meaneth the fracas? Where is the guard? Why don't some of them jab their steel in the blasphemous ragamuffins who thus make mock of the holy offices of religion? Take that, you black, sprawling beast!"

He aimed a vicious stroke at my head, which I ducked in the nick of time to permit of its landing with full force in my companion's ribs. I heard him grunt in acknowledgment of its receipt.

"Where is the guard, I say! If they come not I will strangle the dogs with my own consecrated hands to the glory of God. By the sainted Benedine! was ever one of our Order so basely treated before? Get away, I tell you! 'Tis a disgrace to the true faith, and just as I was about to bring the Chevalier to his knees in confession of his sins!"

Gonzales was fairly doubled up with laughter at the ludicrous incident, choking so that speech had become an utter impossibility. By this time the aroused guards began hurrying forward on a run down the passageway to rescue their imperilled comrade, yet, before the foremost succeeded in laying hands upon me, a newcomer, resplendent in glittering uniform, with an inflamed, almost purple face, leaped madly forth from the opposite side of the mast and began laying about him vigorously with an iron pin, making use meanwhile of a vocabulary of choice Spanish epithets such as I never heard equalled.

"By the shrine of Saint Gracia!" shouted this new arrival hoarsely, glaring about in the dim light as if half awakened from a bad dream. "What meaneth this aboard my ship? Caramba! is this a travelling show—a place for mountebanks and gypsies? Shut the door, you shrieking gray-back of a monk, or I 'll have you cat-o'-nine-tailed by the guard, in spite of your robe. Get up, you drunken brute!"

The crestfallen soldier to whom these last affectionate words were addressed limped painfully away, and then the justly irate commander of His Christian Majesty's flag-ship "Santa Maria" glowered down on me with an astonishment that for the moment held him dumb.

"Where did this dirty nigger come from?" he roared at last, applying one of his heavy sea-boots to me with vehemence. "Who is the villain who dared bring such cattle on board my ship?"

Gonzales, now thoroughly sobered by the seriousness of the situation, attempted to account for my presence, but before he had fairly begun his story, the Captain, who by this time was beyond all reason, burst roaring forth again:

"Oh, so you brought him! You did, hey? Well, did n't I tell you to let no lazy, loafing bumboat-man set foot on board? Do you laugh at my orders, you good-for-nothing scum of the sea? And above all things why did you ever drag such a creature as this down between decks to disgrace the whole of His Majesty's navy? Get up, you bundle of rags!"

I scrambled to my feet, seeking to shuffle to one side out of his immediate sight, but a heavy hand closed instantly on my ragged collar and held me fronting him. For a moment I thought he meant to strike me, but I appeared such a miserable, dejected specimen of humanity that the fierce anger died slowly out of his eyes.

"Francisco," he called sternly, "heave this thing overboard, and be lively about it! Saints of Mercy! he smells like a butcher-boat in the tropics."

Hustled, dragged, cuffed, mercilessly kicked, the fellows got me out upon the open deck at last; I caught one fleeting glimpse of the great masts, the white, gleaming planks under foot, the horrified, upturned, face of Alphonse in the little boat beneath, and then, with a heave and a curse, over I went, sprawling down from rail to river, as terrified a darky as ever made hasty departure from a man-of-war.