The Project Gutenberg EBook of Riding for Ladies, by W. A. Kerr This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Riding for Ladies Author: W. A. Kerr Release Date: May 4, 2012 [EBook #39610] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RIDING FOR LADIES *** Produced by Julia Miller and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

PREFACE.

This work should be taken as following on, and in conjunction with, its predecessor on "Riding." In that publication will be found various chapters on Action, The Aids, Bits and Bitting, Leaping, Vice, and on other cognate subjects which, without undue repetition, cannot be reintroduced here. These subjects are of importance to and should be studied by all, of either sex, who aim at perfection in the accomplishment of Equitation, and who seek to control and manage the saddle-horse.

W. A. K.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | The Lady's Horse | 6 |

| III. | Practical Hints: How to Mount, 14 —The Seat, 22—The Walk, 27—The Trot, 33—The Canter, 39—The Hand-Gallop and Gallop, 44—Leaping, 46—Dismounting, 51 | |

| IV. | The Side Saddle | 52 |

| V. | Hints Upon Costume | 63 |

| VI. | À la Cavalière | 73 |

| VII. | Appendix I.—The Training of Ponies for Children | 81 |

| Appendix II.—Extension and Balance Motions | 89 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE | |

| Preparing to Mount | 17 |

| Mounting—Second Position | 19 |

| Mounted—Near Side | 22 |

| Right and Wrong Elbow Action | 26 |

| Right and Wrong Mount | 28 |

| Turning in the Walk—Right and Wrong Way | 31 |

| Right and Wrong Rising | 34 |

| The Trot | 38 |

| Free but not Easy | 43 |

| The Leap | 48 |

| The Side Saddle, Old Style | 53 |

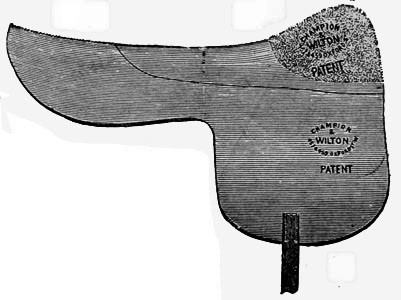

| The Safety Saddle | 54 |

| Saddles | 55-62 |

| The "Zenith" Habit—Jacket Body | 65 |

| Costumes | 78 |

RIDING FOR LADIES.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTORY.

What I have said on the excellence of horse-exercise for boys and men, applies equally to girls and women, if, indeed, it does not recommend itself more especially in the case of the latter. For the most part the pursuits of women are so quiet and sedentary that the body is rarely called into that complete activity of all the muscles which is essential to their perfect development, and which produces the strength and freedom of movement so indispensable to perfect grace of carriage.

The woman who has been early accustomed to horse-exercise gains a courage and nerve which it would be difficult to acquire in a more pleasant and healthful manner. She also gains morally in learning to feel a sympathy with the noble animal to whom she is indebted for so much enjoyment, and whose strength and endurance are too often cruelly abused by man. Numerous instances have occurred in my experience of the singular influence obtained by ladies over their horses by simple kindness, and I am tempted to introduce here an account of what gentle treatment can effect with the Arab. The lady who told the tale did not lay claim to being a first-rate horsewoman. Her veracity was undoubted, for her whole life was that of a ministering angel. She wrote thus: "I had a horse provided for me of rare beauty and grace, but a perfect Bucephalus in her way. She was only two generations removed from a splendid Arabian, given by the good old king to the Duke of Kent when H.R.H. went out in command to Nova Scotia. The creature was not three years old, and to all appearance unbroken. Her manners were those of a kid rather than of a horse; she was of a lovely dappled gray, with mane and tail of silver, the latter almost sweeping the ground; and in her frolicsome gambols she turned it over her back like a Newfoundland dog. Her slow step was a bound, her swift motion unlike that of any other animal I ever rode, so fleet, so smooth, so unruffled. I know nothing to which I can compare it. Well, I made this lovely creature so fond of me by constant petting, to which, I suppose, her Arab character made her peculiarly sensitive, that my voice had equal power over her, as over my faithful docile dog. No other person could in the slightest degree control her. Our corps, the 73rd Batt. of the 60th Rifles, was composed wholly of the élite of Napoleon's soldiers, taken in the Peninsula, and preferring the British service to a prison. They were, principally, conscripts, and many were evidently of a higher class in society than those usually found in the ranks. Among them were several Chasseurs and Polish Lancers, very fine equestrians, and as my husband had a field-officer's command on detachment, and allowances, our horses were well looked after. His groom was a Chasseur, mine a Pole, but neither could ride "Fairy" unless she happened to be in a very gracious mood. Lord Dalhousie's English coachman afterwards tried his hand at taming her, but all in vain. In an easy quiet manner she either sent her rider over her head or, by a laughable manœuvre, sitting down like a dog on her haunches, slipped him off the other way. Her drollery made the poor men so fond of her that she was rarely chastised, and such a wilful, intractable wild Arab it would be hard to find. Upon her I was daily mounted. Inexperienced in riding, untaught, unassisted, and wholly unable to lay any check upon so powerful an animal, with an awkward country saddle, which, by some fatality, was never well fixed, bit and bridle to match, and the mare's natural fire increased by high feed, behold me bound for the wildest paths in the wildest regions of that wild country. But you must explore the roads about Annapolis, and the romantic spot called the "General's Bridge," to imagine either the enjoyment or the perils of my happiest hour. Reckless to the last degree of desperation, I threw myself entirely on the fond attachment of the noble creature; and when I saw her measuring with her eye some rugged fence or wild chasm, such as it was her common sport to leap over in her play, the soft word of remonstrance that checked her was uttered more from regard to her safety than my own. The least whisper, a pat on the neck, or a stroke down the beautiful face that she used to throw up towards mine, would control her; and never for a moment did she endanger me. This was little short of a daily miracle, when we consider the nature of the country, her character, and my unskilfulness. It can only be accounted for on the ground of that wondrous power which, having willed me to work for a time in the vineyard of the Lord, rendered me immortal till the work should be done. Rather, I should say, in the words of Cooper, which I have ventured to slightly vary—

"'Tis plain the creature whom He chose to invest

With queen-ship and dominion o'er the rest,

Received her nobler nature, and was made

Fit for the power in which she stands arrayed."

Strongly as I advocate early tuition, if a girl has not mounted a horse up to her thirteenth year, my advice is to postpone the attempt, unless thoroughly strong, for a couple of years at least. I cannot here enter the reason why, but it is good and sufficient. Weakly girls of all ages, especially those who are growing rapidly, are apt to suffer from pain in the spine. "The Invigorator" corset I have recommended under the head of "Ladies' Costume" will, to some extent, counteract this physical weakness; but the only certain cures are either total cessation from horse exercise, or the adoption of the cross, or Duchess de Berri, seat—in plain words, to ride à la cavalière astride in a man's saddle. In spite of preconceived prejudices, I think that if ladies will kindly peruse my short chapter on this common sense method, they will come to the conclusion that Anne of Luxembourg, who introduced the side-saddle, did not confer an unmixed benefit on the subjects of Richard the Second, and that riding astride is no more indelicate than the modern short habit in the hunting field. We are too apt to prostrate ourselves before the Juggernaut of fashion, and to hug our own conservative ideas.

Though the present straight-seat side-saddle, as manufactured by Messrs. Champion and Wilton, modifies, if it does not actually do away with, any fear of curvature of the spine; still, it is of importance that girls should be taught to ride on the off-side as well as the near, and, if possible, on the cross-saddle also. Undoubtedly, a growing girl, whose figure and pliant limbs may, like a sapling, be trained in almost any direction, does, by always being seated in one direction, contract a tendency to hang over to one side or the other, and acquire a stiff, crooked, or ungainly seat. Perfect ease and squareness are only to be acquired, during tuition and after dismissal from school, by riding one day on the near and the next on the off-side. This change will ease the horse, and, by bringing opposite sets of muscles into play, will impart strength to the rider and keep the shoulders level. Whichever side the rider sits, the reins are held, mainly, in the left hand—the left hand is known as the "bridle-hand." Attempts have frequently been made to build a saddle with two flaps and movable third pommel, but the result has been far from satisfactory. A glance at a side-saddle tree will at once demonstrate the difficulty the saddler has to meet, add to this a heavy and ungainly appearance. The only way in which the shift can be obtained is by having two saddles.

NAOMI (A HIGH-CASTE ARABIAN MARE).

CHAPTER II.

THE LADY'S HORSE.

There is no more difficult animal to find on the face of the earth than a perfect lady's horse. It is not every one that can indulge in the luxury of a two-hundred-and-fifty to three-hundred-guinea hack, and yet looks, action, and manners will always command that figure, and more. Some people say, what can carry a man can carry a woman. What says Mrs. Power O'Donoghue to this: "A heavy horse is never in any way suitable to a lady. It looks amiss. The trot is invariably laboured, and if the animal should chance to fall, he gives his rider what we know in the hunting-field as 'a mighty crusher.' It is indeed, a rare thing to meet a perfect 'lady's horse.' In all my wide experience I have met but two. Breeding is necessary for stability and speed—two things most essential to a hunter; but good light action is, for a roadster, positively indispensable, and a horse who does not possess it is a burden to his rider, and is, moreover, exceedingly unsafe, as he is apt to stumble at every rut and stone."

Barry Cornwall must have had something akin to perfection in his mind's eye when penning the following lines:—

"Full of fire, and full of bone,

All his line of fathers known;

Fine his nose, his nostrils thin,

But blown abroad by the pride within!

His mane a stormy river flowing,

And his eyes like embers glowing

In the darkness of the night,

And his pace as swift as light.

Look, around his straining throat

Grace and shifting beauty float!

Sinewy strength is in his reins,

And the red blood gallops through his veins."

How often do we hear it remarked of a neat blood-looking nag, "Yes, very pretty and blood-like, but there's nothing of him; only fit to carry a woman." No greater mistake can be made, for if we consider the matter in all its bearings, we shall see that the lady should be rather over than under mounted.

The average weight of English ladies is said to be nine stone; to that must be added another stone for saddle and bridle (I don't know if the habit and other habiliments be included in the nine stone), and we must give them another stone in hand; or eleven stone in all. A blood, or at furthest, two crosses of blood on a good foundation, horse will carry this weight as well as it can be carried. It is a fault among thoroughbreds that they do not bend the knee sufficiently; but there are exceptions to this rule. I know of two Stud Book sires, by Lowlander, that can trot against the highest stepping hackney or roadster in the kingdom, and, if trained, could put the dust in the eyes of nine out of ten of the much-vaunted standard American trotters. Their bold, elegant, and elastic paces come up to the ideal poetry of action, carrying themselves majestically, all their movements like clockwork, for truth and regularity. The award of a first prize as a hunter sire to one of these horses establishes his claim to symmetry, but, being full sixteen hands and built on weight-carrying lines, he is just one or two inches too tall for carrying any equestrienne short of a daughter of Anak.

Though too often faulty in formation of shoulders, thoroughbreds, as their name implies, are generally full of quality and, under good treatment, generous horses. I do not chime in with those who maintain that a horse can do no wrong, but do assert that he comes into the world poisoned by a considerably less dose of original sin than we, who hold dominion over him, are cursed with.

Two-year-olds that have been tried and found lacking that keen edge of speed so necessary in these degenerate days of "sprinting," many of them cast in "beauty's mould," are turned out of training and are to be picked up at very reasonable prices. Never having known a bit more severe than that of the colt-breaker and the snaffle, the bars of their mouths are not yet callous, and being rescued from the clutches of the riding lads of the training-stable, before they are spoiled as to temper, they may, in many instances, under good tuition, be converted into admirable ladies' horses—hacks or hunters. They would not be saleable till four years old, but seven shillings a week would give them a run at grass and a couple of feeds of oats till such time as they be thoroughly taken in hand, conditioned, and taught their business. The margin for profit on well bought animals of this description, and their selling price as perfect lady's horses, are very considerable.

In my opinion no horse can be too good or too perfectly trained for a lady. Some Amazons can ride anything, play cricket, polo, golf, lawn-tennis, fence, scale the Alps, etc., and I have known one or two go tiger-shooting. But all are not manly women, despite fashion, trending in that unnatural, unlovable direction. One of their own sex describes them as "gentle, kindly, and cowardly." That all are not heroines, I admit, but no one who witnessed or even read of their devoted courage during the dark days of the Indian mutiny, can question their ability to face terrible danger with superlative valour. The heroism of Mrs. Grimwood at Manipur is fresh in our memory. What the majority are wanting in is nerve. I have seen a few women go to hounds as well and as straight as the ordinary run of first-flight men. That I do not consider the lady's seat less secure than that of the cross-seated sterner sex, may be inferred from the sketch of the rough-rider in my companion volume for masculine readers, demonstrating "the last resource," and giving practical exemplification of the proverb, "He that can quietly endure overcometh." What women lack, in dealing with an awkward, badly broken, unruly horse, is muscular force, dogged determination, and the ability to struggle and persevere. Good nerve and good temper are essentials.

Having given Barry Cornwall's poetic ideal of a horse, I now venture on a further rhyming sketch of what may fairly be termed "a good sort":—

"With intelligent head, lean, and deep at the jowl,

Shoulder sloping well back, with a skin like a mole,

Round-barrelled, broad-loined, and a tail carried free,

Long and muscular arms, short and flat from the knee,

Great thighs full of power, hocks both broad and low down,

With fetlocks elastic, feet sound and well grown;

A horse like unto this, with blood dam and blood sire,

To Park or for field may to honours aspire;

It's the sort I'm in want of—do you know such a thing?

'Tis the mount for a sportswoman, and fit for a queen!"

My unhesitating advice to ladies is Never buy for yourself. Having described what you want to some well-known judge who is acquainted with your style of riding, and who knows the kind of animal most likely to suit your temperament, tell him to go to a certain price, and, if he be a gentleman you will not be disappointed. You won't get perfection, for that never existed outside the garden of Eden, but you will be well carried and get your money's worth. Ladies are not fit to cope with dealers, unless the latter be top-sawyers of the trade, have a character to lose, and can be trusted. There has been a certain moral obliquity attached to dealing in horses ever since, and probably before, they of the House of Togarmah traded in Tyrian fairs with horses, horsemen, and mules. Should your friend after all his trouble purchase something that does not to the full realize your fondest expectation, take the will for the deed, and bear in mind "oft expectation fails, and most oft there where most it promises."

With nineteen ladies out of every score, the looks of a horse are a matter of paramount importance: he must be "a pretty creature, with beautiful deer-like legs, and a lovely head." Their inclinations lead them to admire what is beautiful in preference to what is true of build, useful, and safe. If a lady flattered me with a commission to buy her a horse, having decided upon the colour, I should look out for something after this pattern: one that would prove an invaluable hack, and mayhap carry her safely and well across country.

Height fifteen two, or fifteen three at the outside; age between six and eight, as thoroughbred as Eclipse or nearly so. The courage of the lion yet gentle withal. Ears medium size, well set on, alert; the erect and quick "pricking" motion indicates activity and spirit. I would not reject a horse, if otherwise coming up to the mark, for a somewhat large ear or for one slightly inclined to be lopped, for in blood this is a pretty certain indication of the Melbourne strain, one to which we are much indebted. The characteristics of the Melbournes are, for the most part, desirable ones: docility, good temper, vigorous constitution, plenty of size, with unusually large bone, soundness of joints and abundance of muscle. But these racial peculiarities are recommendations for the coverside rather than for the Park. The eye moderately prominent, soft, expressive, "the eye of a listening deer." The ears and the eyes are the interpreters of disposition. Forehead broad and flat. A "dish face," that is, slightly concave or indented, is a heir-loom from the desert, and belongs to Nejd. The jaws deep, wide apart, with plenty of space for the wind-pipe when the head is reined in to the chest. Nostrils long, wide, and elastic, exhibiting a healthy pink membrane. We hear a good deal of large, old-fashioned heads, and see a good many of the fiddle and Roman-nosed type, but, in my opinion, these cumbersome heads, unless very thin and fleshless, are indicative of plebeian blood.

The setting on of the head is a very important point. The game-cock throttle is the right formation, giving elasticity and the power to bend in obedience to the rider's hand. What the dealers term a fine topped horse, generally one with exuberance of carcase and light of limbs, is by no means "the sealed pattern" for a lady; on the contrary, the neck should be light, finely arched—that peculiarly graceful curve imported from the East,—growing into shoulders not conspicuous for too high withers. "Long riding shoulders" is an expression in almost every horseman's mouth, but very high and large-shouldered animals are apt to ride heavy in hand and to be high actioned. Well-laid-back shoulders, rather low, fine at the points, not set too far apart, and well-muscled will be found to give pace with easy action.

He should stand low on the legs, which means depth of fore-rib, so essential in securing the lady's saddle, as well as ensuring the power and endurance to sustain and carry the rider's weight in its proper place. Fore-legs set well forward, with long, muscular arms, and room to place the flat of the hand between the elbows and the ribs. The chest can hardly be too deep, but it can be too wide, or have too great breadth between the fore-legs. The back only long enough to find room for the saddle is the rule, though, in case of a lady's horse, a trifle more length unaccompanied by the faintest sign of weakness, will do no harm. For speed, a horse must have length somewhere, and I prefer to see it below, between the point of the elbow and the stifle joint. Ormonde, "the horse of the century," was nearly a square, i.e. the height from the top of the wither to the ground almost equalled the length of his body from the point of the shoulder to the extremity of the buttock. Horses with short backs and short bodies are generally buck-leapers, and difficult to sit on when fencing. The couplings or loins cannot be too strong or the ribs too well sprung; the back ribs well hooped. This formation is a sign of a good constitution. The quarters must needs be full, high set on, with straight crupper, well rounded muscular buttocks, a clean channel, with big stifles and thighs to carry them. Knees and hocks clean, broad, and large, back sinews and ligaments standing well away from the bone, flat and hard as bands of steel; short well-defined smooth cannons; pasterns nicely sloped, neither too long nor too short, but full of spring; medium sized feet, hard as the nether millstone. If possible, I should select one endowed with the characteristic spring of the Arab's tail from the crupper. Such a horse would, in the words of Kingsley, possess "the beauty of Theseus, light but massive, and light, not in spite of its masses, but on account of the perfect disposition of them."

There is no need for the judge to run the rule, or the tape either, over the horse. His practised eye, almost in a glance, will take in the general contour of the animal; it will tell him whether the various salient and important points balance, and will instantly detect any serious flaw. When selecting for a lady who, he knows, will appreciate sterling worth rather than mere beauty, he may feel disposed to gloss over a certain decidedness of points and dispense with a trifle of the comely shapeliness of truthfully moulded form. Having satisfied myself that the framework is all right, I would order the horse to be sauntered away from me with a loose rein, and, still with his head at perfect liberty, walked back again. I would then see him smartly trotted backwards and forwards. Satisfied with his natural dismounted action, I should require to see him ridden in all his paces, and might be disposed to get into the saddle myself. Having acquitted himself to my satisfaction, he would then have to exhibit himself in the Park or in a field, ridden in the hands of some proficient lady-rider. A few turns under her pilotage would suffice to decide his claims to be what I am looking for. If he came up to my ideas of action, or nearly so, I should not hesitate—subject to veterinary certificate of soundness—to purchase. Finally, the gentleman to examine the horse as to his soundness would be one of my own selection. Certain of the London dealers insist upon examinations being made by their own "Vets," and "there's a method in their madness." When such a stipulation is made, I invariably play the return match by insisting upon having the certificate of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, where the investigation is complete and rigorous. The very name of "the College" is gall and wormwood to many of these "gentlemen concerned about horses."

CHAPTER III.

PRACTICAL HINTS.

How To Mount.

Previous to mounting, the lady should make a practice of critically looking the horse over, in order to satisfy herself that he is properly saddled and bridled. Particular attention should be paid to the girthing. Though ladies are not supposed to girth their own horses, occasion may arise, in the Colonies especially, when they may be called upon to perform that office. Information on this essential and too oft-neglected point may not be out of place. Odd as it may sound, few grooms know how to girth a horse properly, and to explain myself I must, for a few lines, quit the side-saddle for the cross-saddle. Men often wonder how it is that, on mounting, the near stirrup is almost invariably a hole or more the longer of the two. The reason is this: the groom places the saddle right in the centre of the horse's back and then proceeds to tighten the girths from the near or left side. The tension on the girth-holder, all from one side, cants the saddle over to the left, to which it is still further drawn by the weight of the rider in mounting and the strain put upon it by the act of springing into the saddle. This list to port can easily be obviated by the groom placing the heel of his left hand against the near side of the pommel, guiding the first or under-girth with the right hand till the girth-holder passes through the buckle and is moderately tight, then, with both hands, bracing it so that room remains for one finger to be passed between it and the horse. The same must be done in the case of the outer girth.

In a modified degree the side-saddle is displaced by the common mode of girthing. The surcingle should lie neatly over the girths, and have an equal bearing with them. When the "Fitzwilliam girth" is used—and its general use is to be advocated, not only on account of its safety and the firmness of the broad web, but for its freedom from rubbing the skin behind the elbow—the leather surcingle of the saddle will take the place of the usual leather outside strap supplied with this girth.

For inspection the horse should be brought up to the lady, off side on. She should note that the throat-lash falls easily, but not dangling, on the commencement of the curve of the cheek-bone, and that it is not buckled tight round the throttle, like a hangman's "hempen-tow." The bridoon should hang easily in the mouth, clear of the corners or angles, and not wrinkling them; the curb an inch or so above the tusk, or, in the case of a mare, where that tooth might be supposed to be placed. She will see that the curb-chain is not too tight, that the lip-strap is carried through the small ring on the chain, also that the chain lies smooth and even. In fixing the curb, if the chain be turned to the right, the links will unfold themselves. It is taken for granted that by frequent personal visits to the stable, or by trusty deputy, she is satisfied that the horse's back and withers are not galled or wrung. A groom withholding information on this point should, after one warning, get his congé. That the bits and stirrup be burnished as bright as a Life Guardsman's cuirasse, the saddle and bridle perfectly clean, and the horse thoroughly well groomed, goes without saying. All the appointments being found in a condition fit for Queen's escort duty, we now proceed to put the lady in, not into, her saddle. She should approach the horse from the front, and not from behind.

After a kind word or two and a little "gentling," she, with her whip, hunting crop, or riding cane in her right hand, picks up the bridoon rein with her left, draws it through the right smoothly and evenly, feeling the horse's mouth very lightly, until it reaches the crutch, which she takes hold of. In passing the rein through the hand, care must be taken that it is not allowed to slacken so that touch of the mouth is lost. Attention to this will keep the horse in his position whilst being mounted; for should he move backward or forward or away as the lady is in the act of springing into the saddle, he not only makes the vaulting exceedingly awkward, but dangerous. Many horses sidle away as the lady is balanced on one foot and holding on to the pommel with the right hand, in which case she must at once quit her hold or a fall will follow.

Having adjusted the rein of the bridoon to an equal length, the whip point down with the end of the rein on the off side, she stands looking in the direction the horse is standing—i.e., to her proper front, her right shoulder and arm in contact with the flap of the saddle near side. The mounter advances facing her, and, close to the horse's shoulder, can perform his office in three different ways. Stooping down, he places his right hand, knuckles downwards, on his right knee, and of it the lady makes a sort of mounting block, whence, springing from the left foot, she reaches her saddle. When she springs she has the aid of her grip on the crutch, supplemented by the raising power of her left hand resting on the man's shoulder. Or the groom aids the spring by the uplifting of both the hand and the knee. The third method is, for the mounter—his left arm, as before, touching the horse's shoulder—to stoop down till his left shoulder comes within easy reach of the lady's left hand, which she lays on it. He at the same time advances his left foot till it interposes between her and the horse and makes a cradle of his hands, into which she places her left foot. Her grip is still on the crutch, and she still feels the horse's mouth. One, two, three! she springs like feathered Mercury, and he, straightening himself, accentuates the light bound, and straightway she finds herself in the saddle.

PREPARING TO MOUNT.

It is dangerous to face the mounter in such a position that the spring is made with the rider's back to her horse's side, for in the event of his starting suddenly or "taking ground to her right," an awkward full-length back-fall may result. The foot must be placed firmly in the mounter's hand; during the lift it must not be advanced, but kept under her, and he must not attempt to raise her till her right foot be clear of the ground. The best plan that can be adopted with a horse in the habit of moving away to one side is to stand him against a low wall or paling, or alongside another horse. A quiet, well-trained horse may stand as firm as one of the British squares at Waterloo, or "the thin red line" at Balaclava, for times without number, but from some unforeseen alarm may suddenly start aside. The spring and lift must go together, or the lady may, like Mahomet's coffin, find herself hanging midway. Practice alone can teach the art of mounting lightly and gracefully, and to an active person there is no difficulty.

There is yet another method of mounting which requires considerably more practice—doing away with the services of a mounter,—and that is for the lady to mount herself. In these days, when so many ladies practise gymnastics and athletic exercises generally, there ought to be no difficulty in acquiring this useful habit. The stirrup is let out till it reaches to about a foot from the ground, the pommel is grasped with the right hand, and with a spring the rider is in her seat. The stirrup is then adjusted to its proper length. Unless the horse be very quiet the groom must stand at his head during this process of mounting.

Mounting from a chair or a pair of steps is certainly not an accomplishment I should recommend ladies to indulge in; still, there are occasions when the friendly aid of a low wall, a stile, the bar of a gate, or even a wheelbarrow, comes handy. In such a predicament, take the bridoon across the palm of the left hand, and drawing the bit rein through on each side of the little or third finger till the horse's mouth be felt, place the right foot in the stirrup, grasp the leaping-head with the left and the upright pommel with the right hand, and spring into the saddle, turning round, left about, in so doing. When in the saddle, disengage the right foot from the stirrup and throw the right leg over the upright head.

MOUNTING—SECOND POSITION.

When the lady is in the saddle, that is, seated on it, not in riding position but before throwing her right leg over the crutch, the groom, without releasing the hold of her foot altogether, adjusts the folds of the habit, care being taken that there is no crease or fold between the right knee and the saddle. This, in the case of a Zenith, is a matter speedily arranged, and, the adjustment being to her satisfaction, she at once pivots on the centre, and raises her right leg into its place over the crutch. The foot is then placed in the stirrup. When a good seat has been acquired, and the rider does not encumber herself with needless underclothing, this arrangement of habit had best be deferred till the horse is in motion; she can then raise herself in the saddle by straightening the left knee, and, drawing herself forward by grasping the pommel with the right hand, arrange the folds to her entire satisfaction with the left.

Attention must be paid to the length of the stirrup, for on it depends greatly the steadiness of the seat. Many ladies are seen riding with a short stirrup; but this is an error, for it destroys the balance, without which there can be no elegance, invariably causes actual cramp and gives a cramped appearance, forces the rider out of the centre of the saddle, so that the weight on the horse's back is unevenly distributed, and displays too much daylight when rising in the trot. On the other hand, too long a stirrup is equally objectionable, as it causes the body to lean unduly over to the near side in order to retain hold of it, depresses and throws back the left shoulder, and destroys the squareness of position. The length of stirrup should be just sufficient that the rider, by leaning her right hand on the pommel, can, without any strain on the instep, raise herself clear of the saddle; this implies that the knee will be only bent sufficiently to maintain the upward pressure of the knee against the concave leaping-head. The stirrup is intended as a support to the foot, not as an appui to ride from; it is not intended to sustain the full weight of the body, and when so misapplied is certain to establish a sore back. I am strongly of opinion that to be in all respects perfect in the equestrian art, a lady should learn, in the first instance, to ride without a stirrup, so as, under any circumstances that may arise, to be able to do without this appendage. Those who aspire to honours in the hunting-field certainly should accustom themselves to dispense with the stirrup, as by so doing they will acquire a closer and firmer seat; moreover, its absence teaches the beginner, better than any other method, to ride from balance, which is the easiest and best form of equitation for both horse and rider. Many horsewomen are under the impression that it is impossible to rise without the aid of the stirrup, but that such is not the case a course of stirrupless training will soon prove. I do not suggest that riding thus should be made a habit, but only strenuously advocate its practice.

A very general fault, and an extremely ugly one among lady riders, is the habit of sticking out the right foot in front of the saddle. It is not only unsightly, but loosens the hold, for if the toe be stuck out under the habit like a flying jib-boom, the leg becomes the bowsprit, and it is impossible for a straightened leg to grip the crutch. Bend the knee well, keep the toe slightly down, and this ugly habit is beyond the pale of possibility. This ungraceful posture may be caused by the pommels being placed so near together that there is not sufficient room for the leg to lie and bend easily, but this excuse will not hold good in the case of the straight-seat-safety-side-saddle, for it has only one pommel or crutch and one leaping-head.

Having got the lady into her saddle, we next attempt so to instruct her that it may be remarked—

"The rider sat erect and fair."—Scott.

The Seat.

Hitherto, during the process of mounting and settling herself comfortably, the reins have been in the rider's right hand. Now that women can sit square and look straight out and over their horses' ears, much more latitude is permitted in the hold of the reins. It is no longer essential to hold them only in the left hand, for as often as not—always in hunting or at a hand-gallop—both hands are on the bridle. But, as a rule, the left should be the bridle hand, for if the reins be held in the right, and the horse, as horses often will, gets his head down or bores, the right shoulder is drawn forward, and the left knee, as a matter of course, being drawn back from under, loses its upward pressure against the leaping-head, and the safety of the seat is jeopardized. Were the rein to give way the rider would probably fall backwards off the horse over his off-quarter. On the other hand, when the reins are all gathered into the left hand, the harder the horse may take the bit in his teeth, and the lower he may carry his head, the firmer must be the grip of the crutch and the greater the pressure against the leaping-head.

MOUNTED—NEAR SIDE.

As the reins must not be gathered up all in a bunch, I give the following directions for placing them in the hand. If riding with a snaffle, as always should be the case with beginners, the reins ought to be separated, passing into the hands between the third and fourth fingers, and out over the fore or index-finger, where they are held by the thumb. In the case of bit and bridoon (the bridoon rein has generally a buckle where it joins, whereas that of the bit is stitched), take up the bridoon rein across the inside of the hand, and draw the bit rein through the hand on each side of the little or third finger until the mouth of the horse be gently felt; turn the remainder of the rein along the inside of the hand, and let it fall over the forefinger on to the off-side; place the bridoon rein upon those of the bit, and close the thumb upon them all.

A second plan equally good is, when the horse is to be ridden mainly on the bridoon: the bridoon rein is taken up by the right hand and drawn flatly through on each side of the second finger of the bridle-hand, till the horse's mouth can be felt, when it is turned over the first joint of the forefinger on to the off-side. The bit rein is next taken up and drawn through on each side of the little finger of the bridle-hand, till there is an equal, or nearly equal, length and feeling with the bridoon, and then laid smoothly over the bridoon rein, with the thumb firmly placed as a stopper upon both, to keep them from slipping. A slight pressure of the little finger will bring the bit into play.

Thirdly, when the control is to be entirely from the bit or curb; the bit rein is taken up by the stitching by the right hand within the bridoon rein, and drawn through on each side of the little finger of the left or bridle-hand, until there is a light and even feel on the horse's mouth; it is then turned over the first joint of the forefinger on the off-side. The bridoon rein is next taken up by the buckle, under the left hand, and laid smoothly over the left bit rein, leaving it sufficiently loose to hang over each side of the horse's neck. The thumb is then placed firmly on both reins, as above.

These different manipulations of the reins may be conveniently practised at home with reins attached to an elastic band, the spring of the band answering to the "feel" on the horse's mouth. But, in addition to these various systems of taking up the reins, much has to be learnt in the direction of separating, shortening, shifting, and so forth. With novices the reins constantly and imperceptibly slip, in which case, the ends of the reins hanging over the forefinger of the bridle-hand are taken altogether into the right, the right hand feels the horse's head, while the loosened fingers of the bridle-hand are run up or down the reins, as required, till they are again adjusted to the proper length, when the fingers once more close on them.

In shifting reins to the right hand, to relieve cramp of the fingers, and so forth, the right hand must always pass over the left, and in replacing them the left hand must be placed over the right. In order to shorten any one rein, the right hand is used to pull on that part which hangs beyond the thumb and forefinger. When a horse refuses obedience to the bridle-hand, it must be reinforced by the right. The three first fingers of the right are placed over the bridoon rein, so that the rein passes between the little and third fingers, the end is then turned over the forefinger and, as usual, the thumb is placed upon it. Expertness in these "permutations and combinations" is only to be arrived at by constant practice. They must be performed without stopping the horse, altering his pace, or even glancing at the hands.

The reins must not be held too loose, but tight enough to keep touch of the horse's mouth; and, on the other hand, there must be no attempt to hold on by the bridle, or what is termed to "ride in the horse's mouth." A short rein is objectionable; there must be no "extension motions," no reaching out for a short hold. The proper position for the bridle-hand is immediately opposite the centre of the waist, and about three or four inches from it, that is, on a level with the elbow, and about three or four inches away from the body. The elbow must neither be squeezed or trussed too tightly to the side, nor thrust out too far, but carried easily, inclining a little from the body. According to strict manège canons, the thumb should be uppermost, and the lower part of the hand nearer the waist than the upper, the wrist a little rounded, and the little finger in a line with the elbow. A wholesome laxity in conforming to these hard-and-fast rules will be found to add to the grace of the rider. Chaque pays chaque guise, and no two horses are alike in the carriage of the head, the sensitiveness of the mouth, and in action. Like ourselves, they all have their own peculiarities.

THE RIGHT AND WRONG ELBOW ACTION.

The Walk.

The rider is now seated on what—in the case of a beginner—should be an absolutely quiet, good-tempered, and perfectly trained horse. Before schooling her as to seat, we will ask her to move forward at the walk. At first it is better to have the horse led by a leading rein till the débutante is accustomed to the motion and acquires some stock of confidence. She must banish from her mind all thoughts of tumbling off. We do not instruct after this fashion:—Lady (after having taken several lessons at two guineas a dozen) loq.: "Well, Mr. Pummell, have I made any good progress?" "Well, I can't say, ma'am," replies the instructor, "as 'ow you rides werry well as yet, but you falls off, ma'am, a deal more gracefuller as wot you did at first." We do not say that falls must not be expected, but in mere hack and park riding they certainly ought to be few and far between. At a steady and even fast walk the merest tyro cannot, unless bent on experiencing the sensation of a tumble, possibly come to the ground. Doubtless the motion is passing strange at first, and the beginner may be tempted to clutch nervously at the pommel of her saddle, a very bad and unsightly habit, and one that, if not checked from the very first, grows apace and remains.

It is during the walk that the seat is formed, and the rider makes herself practically acquainted with the rules laid down on the handling of the reins. A press of the left leg, a light touch of the whip on the off-side, and a "klk" will promptly put the horse in motion. He may toss his head, and for a pace or two become somewhat unsteady; this is not vice but mere freshness, and he will almost immediately settle down into a quick, sprightly step, measuring each pace exactly, and marking regular cadence, the knee moderately bent, the leg, in the case of what Paddy terms "a flippant shtepper," being sharply caught up, appearing suspended in the air for a second, and the foot brought smartly and firmly, without jar, to the ground. This is the perfection of a walking pace. By degrees any nervousness wears off, the rigid trussed appearance gives place to one of pliancy and comparative security, the body loses its constrained stiffness, and begins to conform to and sway with the movements of the horse. The rider, sitting perfectly straight and erect, approaches the correct position, and lays the foundation of that ease and bearing which are absolutely indispensable.

RIGHT MOUNT. WRONG MOUNT.

After a lesson or two, if not of the too-timid order, the lady will find herself sitting just so far forward in the saddle as is consistent with perfect ease and comfort, and with the full power to grasp the upright crutch firmly with her right knee; she will be aware of the friendly grip of the leaping-head over her left leg; the weight of her body will fall exactly on the centre of the saddle; her head, though erect, will be perfectly free from constraint, the shoulders well squared, and the hollow of the back gracefully bent in, as in waltzing. This graceful pose of the figure may be readily acquired, throughout the preliminary lessons, and indeed on all occasions when under tuition, by passing the right arm behind the waist, back of the hand to the body, and riding with it in that position. Another good plan, which can only be practised in the riding-school or in some out-of-the-way quiet corner, and then only on a very steady horse, is for the beginner, without relaxing her grip on the crutch and the pressure on the leaping-head, as she sits, to lean or recline back so that her two shoulder-blades touch the hip-bones of the horse, recovering herself and regaining her upright position without the aid of the reins. The oftener this gymnastic exercise is performed the better.

At intervals during the lessons she should also, having dropped her bridle, assiduously practise the extension motions performed by recruits in our military-riding schools. [See Appendix.] The excellent effects of this physical training will soon be appreciated. But, irrespective of the accuracy of seat, suppleness and strength of limb, confidence and readiness these athletic exercises beget, they may, when least expected, save the rider's life. Some of those for whose instruction I have the honour to write, may find themselves placed in a critical situation, when the ability to lie back or "duck" may save them from a fractured skull.

Inclining the body forward is, from the notion that it tends towards security, a fault very general with timid riders. Nothing, however, in the direction of safety, is further from the fact. Should the horse, after a visit to the farrier and the usual senseless free use of the smith's drawing and paring-knife, tread upon a rolling stone and "peck," the lady, leaning forward, is suddenly thrown still further forward, her whole weight is cast upon his shoulders, so he "of the tender foot" comes down and sends his rider flying over his head. A stoop in the figure is wanting in smartness, and is unattractive.

TURNING IN THE WALK—RIGHT AND WRONG WAY.

It is no uncommon thing to see ladies sitting on their horses in the form of the letter S, and the effect can hardly be described as charming. This inelegant position, assumed by the lady in the distance, is caused by being placed too much over to the right in the saddle, owing to a too short stirrup. In attempting to preserve the balance, the body from the waist upwards has a strong twisted lean-over to the left, the neck, to counteract this lateral contortion of the spine, being bent over to the right, the whole pose conveying the impression that the rider must be a cripple braced up in surgeon's irons and other appliances. Not less hideous, and equally prevalent, is the habit of sitting too much to the left, and leaning over in that direction several degrees out of the perpendicular. A novice is apt to contract this leaning-seat from the apprehension, existing in the mind of timid riders, that they must fall off from the off rather than from the near side, so they incline away from the supposed danger. Too long a stirrup is sometimes answerable for this crab-like posture. In both of these awkward postures, the seat becomes insecure, and the due exercise of the "aids" impossible. What is understood by "aids" in the language of the schools are the motions and proper application of the bridle-hand, leg, and heel to control and direct the turnings and paces of the horse.

The expression "riding by balance" has been frequently used, and as it is the essence of good horsemanship, I describe it in the words of an expert as consisting in "a foreknowledge of what direction any given motion of the horse would throw the body, and a ready adaptation of the whole frame to the proper position, before the horse has completed his change of attitude or action; it is that disposition of the person, in accordance with the movements of the horse, which preserves it from an improper inclination to one side or the other, which even the ordinary paces of the horse in the trot or gallop will occasion." In brief, it is the automatic inclination of the person of the rider to the body of the horse by which the equilibrium is maintained.

The rider having to some extent perfected herself in walking straight forward, inclining and turning to the right and to the right about, and in executing the same movements to the left, on all of which I shall have a few words to say later, and when she can halt, rein back, and is generally handy with her horse at the walk, she may attempt a slow Trot, and here her sorrows may be said to begin.

The Trot.

In this useful but trying pace the lady must sit well down on her saddle, rising and falling in unison with the action of the horse, springing lightly but not too highly by the action of the horse coupled with the flexibility of the instep and the knee. As the horse breaks from the walk into the faster pace, it is best not to attempt to rise from the saddle till he has fairly settled down to his trot—better for a few paces to sit back, somewhat loosely, and bump the saddle. The rise from the saddle is to be made as perpendicularly as possible, though a slight forward inclination of the body from the loins, but not with roached-back, may be permitted, and only just so high as to prevent the jar that ensues from the movements of the rider with the horse not being in unison. The return of the body to the saddle must be quiet, light, and unlaboured. Here it is that the practice without a stirrup will stand the novice in good stead.

This pace is the most difficult of all to ladies, and few there be that attain the art of sitting square and gracefully at this gait, and who rise and fall in the saddle seemingly without an effort and without riding too much in the horse's mouth. Most women raise themselves by holding on to the bridle. Instead of rising to the right, so that they can glance down the horse's shoulder, and descending to left, and thus regain the centre of the saddle, they persist in rising over the horse's left shoulder, and come back on to the saddle in the direction of his off-quarter. This twist of the body to the left destroys the purchase of the foot and knee, and unsteadies the position and hands. Though I have sanctioned a slight leaning forward as the horse breaks into his trot, it must not be overdone, for should he suddenly throw up his head his poll may come in violent contact with the rider's face and forehead, causing a blow that may spoil her beauty, if not knock her senseless.

RIGHT AND WRONG RISING.

Till the rider can hit off the secret of rising, she will be severely shaken up—"churned" as a well-known horsewoman describes the jiggiddy-joggoddy motion,—the teeth feel as if they would be shaken out of their sockets, and stitch-in-the-side puts in its unwelcome appearance. Certes, the preliminary lessons are very trying ones, the disarrangement of "the get-up" too awful, the fatigue dreadful, the alarm no trifle. Nothing seems easier, and yet nothing in the art equestrian is so difficult—not to men with their two stirrups, but to women with one only available. What is more grotesque, ridiculous, and disagreeable than a rider rising and falling in the saddle at a greater and lesser speed than that of her horse? And yet, fair reader, if you will have a little patience, a good deal of perseverance, some determination, and will attend to the hints I give, you shall, in due course, be mistress over the difficulty, and rise and fall with perfect ease and exquisite grace, free from all embarras or undue fatigue.

First of all, we must put you on a very smooth, easy, and sedate trotter; by-and-by we may transfer your saddle to something more sharp and lively, perhaps even indulge you with a mount on a regular "bone-setter." To commence with, the lessons, or rather trotting bouts, shall be short, there shall be frequent halts, and during these halts I shall make you drop your reins and put you through extension and balance motions, endeavour to correct your position on the saddle, catechize you closely on the "aids," and introduce as much variety as possible.

Before urging your steed into his wild six or seven-mile-an-hour career, please bear in mind that you must not rise suddenly, or with a jerk, but quietly and smoothly, letting the impetus come from the motion of the horse. The rise from the saddle must not be initiated by a long pull and strong pull at his mouth, a spasmodic grip of your right leg on the crutch, or a violent attempt to raise yourself in the air from your stirrup. The horse will not accommodate his action to yours, you must "take him on the hop," as the saying is. If horse and rider go disjointly, or you do not harmonize your movements with his, then it is something as unpleasant as dancing a waltz with a partner who won't keep time, or rowing "spoonful about."

Falling in with the trot of a horse is at first very difficult. In order to facilitate matters as much as possible, you shall, for a few days, substitute the old-fashioned slipper for the stirrup, as then the spring will come from the toes and not from the hollow of the foot; this will lessen the exertion and be easier. If nature has happened to fashion you somewhat short from the hip to the knee, and you will attend to instruction and practice frequently, the chances are strong in your favour of conquering the irksome "cross-jolt." Separate your reins, taking one in each hand, feeling the mouth equally with both reins, sit well down on your saddle, keep your left foot pointed straight to the front, don't attempt to move till the horse has steadied into his trot, which, in case of a well trained animal, will be in a stride or two, then endeavour, obeying the impulse of his movement, to time the rise.

A really perfectly broken horse, "supplied on both hands," as it is termed, leads, in the trot as in the canter, equally well with either leg, but, in both paces, a very large majority have a favourite leading leg. By glancing over the right shoulder the time for the rise may be taken. Do not be disheartened by repeated failures to "catch on;" persevere, and suddenly you will hit it off. When the least fatigued, pull up into a walk, and when rested have another try. At the risk of repetition, I again impress on you the necessity of keeping the toe of the left foot pointed to the front, the foot itself back, and with the heel depressed. Your descent into the saddle should be such that any one you may be riding straight at, shall see a part of your right shoulder and hip as they rise and fall, his line of vision being directed along the off-side of the horse's neck. When these two portions of your body are so visible then the weight is in its proper place, and there is no fear of the saddle being dragged over the horse's near shoulder. For a few strides there is no objection to your taking a light hold of the pommel with the right hand, in order to time the rise, but the moment the "cross-jolt" ceases, and you find yourself moving in unison with the horse, the hold must be relaxed. Some difficulty will be found in remaining long enough out of the saddle at each rise to avoid descending too soon, and thus receive a double cross-jolt; but this will be overcome after a few attempts. Keep the hands well down and the elbows in.

THE TROT.

Varying the speed in the trot will be found excellent practice for the hands; the faster a horse goes, generally speaking, the easier he goes. He must be kept going "well within himself," that is he must not be urged to trot at a greater speed than he can compass with true and equal action. Some very fast trotters, "daisy cutters," go with so little upward jerk that it is almost impossible to rise on them at all. Any attempt at half-cantering with his hind legs must be at once checked by pulling him together, and, by slowing him down, getting him back into collected form. Should he "break" badly, from being over-paced, into a canter or hard-gallop, then rein him in, pulling up, if need be, into a walk, chiding him at the same time. When he again brings his head in and begins to step clean, light, and evenly, then let him resume his trot. If not going up to his bit and hanging heavy on the hand, move the bit in his mouth, let him feel the leg, and talk to him. Like ourselves, horses are not up to the mark every day, and though they do not go to heated theatres and crowded ball-rooms, or indulge as some of their masters and mistresses are said to do, they too often spend twenty hours or more out of the twenty-four in the vitiated atmosphere of a hot, badly ventilated stable, and their insides are converted into apothecaries' shops by ignorant doctoring grooms. When a free horse does not face his bit, he is either fatigued or something is amiss.

The Canter.

Properly speaking, this being, par excellence, the lady's pace, the instruction should precede that of the trot. The comparative ease of the canter, and the readiness with which the average pupil takes to it, induces the beginner to at once indulge in it. It is, on a thoroughly trained horse, so agreeable that the uninitiated at once acquire confidence on horseback. Moreover, it is the pace at which a fine figure and elegant lady-like bearing is most conspicuously displayed, and for this, if for no other reason, the pupil applies herself earnestly—shall I say lovingly?—to perfect herself in this delightful feature of the art. On a light-actioned horse, one moving as it were on springs, going well on his haunches, and well up to this bit, the motion is as easy as that of a rocking-chair. All the rider has to do is to sit back, keep the body quite flexible and in the centre of the saddle, preserve the balance, and, with pressure from the left leg and heel, and a touch of the whip, keep him up to his bit. She will imperceptibly leave the saddle at every stride, which, in a slow measured canter, will be reduced to a sort of rubbing motion, just sufficient to ease the slight jolt caused by the action of the haunches and hind legs.

Many park-horses and ladies' hacks are trained to spring at once, without breaking into a run or trot, into the canter. All the rider has to do is to raise the hand ever so little, press him with the leg, touch him with the whip, and give him the unspellable signal "klk." The movement or sway of the body should follow that of the horse. As soon as he is in his stride, the rider throws back her body a little, and places her hand in a suitable position. If the horse carries his head well, the hand ought to be about three inches from the pommel, and at an equal distance from the body. For "star-gazers" it should be lower; and for borers it should be raised higher. Once properly under way the lady will study that almost imperceptible willow-like bend of the back, her shoulders will be thrown back gracefully, the mere suspicion of a swing accommodating itself to the motion of the horse will come from the pliant waist, and she will yield herself just a little to the opposite side from that the horse's leading leg is on. If he leads with the off-foot, he inclines a trifle to the left, and the rider's body and hands must turn but a little to the left also, and vice versâ.

It is the rider's province to direct which foot the horse shall lead with. To canter with the left fore leg leading, the extra bearing will be upon the left rein, the little finger turned up towards the right shoulder, the hint from the whip—a mere touch should suffice—being on the right shoulder or flank. It is essential that the bearing upon the mouth, a light playing touch, should be preserved throughout the whole pace. If the horse should, within a short distance—say a mile or so,—flag, then he must be reminded by gentle application of the whip. He cannot canter truly and bear himself handsomely unless going up to his bit. The rider must feel the cadence of every pace, and be able to extend or shorten the stride at will. It is an excellent plan to change the leading leg frequently, so that upon any disturbance of pace, going "false," or change of direction, the rider may be equal to the occasion. The lady must be careful that the bridle-arm does not acquire the ugly habit of leaving the body and the elbow of being stuck out of it akimbo. All the movements of the hand should proceed from the wrist, the bearings and play on the horse's mouth being kept up by the little finger.

Ladies will find that most horses are trained to lead entirely with the off leg, and that when, from any disturbance of pace, they are forced to "change step" and lead with the near leg, their action becomes very awkward and uneven. Hence they are prone to regard cantering with the near leg as disagreeable. But when they come to use their own horses, they will find it good economy to teach them to change the leading leg constantly, both during the canter and at the commencement of the pace. To make a horse change foot in his canter, if he cannot be got readily to do so by hand, leg, and heel, turn him to the right, as if to circle, and he will lead with the off foreleg, and by repeating the same make-believe manœuvre to the left, the near fore will be in front. The beginner, however, had better pull up into the walk before attempting this change. When pulling up from the canter, it is best and safest to let the horse drop into a trot for a few paces and so resume the walk.

There is no better course of tuition by which to acquire balance than the various inclinations to the right and left, the turns to the right and left and to the right and left-about at the canter, all of which, with the exception of the full turns, should be performed on the move without halting. In the turn-about, it is necessary to bring the horse to a momentary halt before the turn be commenced, and so soon as he has gone about and the turn is fully completed, a lift of the hand and a touch of the leg and heel should instanter compel him to move forward at the canter in the opposite direction; he must no sooner be round than off. When no Riding-school is available, one constructed of hurdles closely laced with gorse, on the sheep-lambing principle, will answer all purposes. Should the horse be at all awkward or unsteady, the hurdles, placed one on the top of the other and tied to uprights driven into the ground, closely interlaced with the gorse so that he cannot see through or over the barrier, will form a perfect, retired exercise ground. A plentiful surface dressing of golden-peat-moss-litter will save his legs and feet. In a quiet open impromptu school of this description, away from "the madding crowd," I have schooled young horses so that they would canter almost on their own ground, circling round a bamboo lance shaft, the point in the ground and the butt in my right hand, without changing legs or altering pace, and they would describe the figure eight with almost mathematical precision, changing leg at every turn without any "aid" from me, a mere inclination of the body bringing them round the curves. A horse very handy with his legs can readily change them at the corners when making the full right-angle turn, but there is always at first the danger of one not so clever attempting to execute the turn by crossing the leading leg over the supporting one, when the rider will be lucky to get off with an awkward stumble—a "cropper" will most likely follow. When at this private practice, "make much of your horse"—that is, caress and speak kindly to him, when he does well; in fact, the more he is spoken to throughout the lesson, the better for both parties. So good and discriminating is a horse's ear that he soon learns to appreciate the difference between kindly approval and stern censure. A sympathy between horse and rider is soon established, and such freemasonry is delightful.

FREE BUT NOT EASY.

Never canter on the high road, and see that your groom does not indulge himself by so doing. On elastic springy turf the pace, which in reality is a series of short bounds, if not continued too long at a time, does no great harm, but one mile on a hard, unyielding surface causes more wear-and-tear of joints, shoulders, and frame generally, than a long day's work of alternating walk and trot which, on the Queen's highway, are the proper paces. There is no objection to a canter when a bit of turf is found on the road-side; and the little drains cut to lead the water off the turnpike into the ditch serve to make young horses handy with their legs.

The Hand-gallop and Gallop.

The rider should not attempt either of these accelerated paces till quite confident that she has the horse under complete control. As the hand-gallop is only another and quickened form of the canter, in which the stride is both lengthened and hastened, or, more correctly speaking, in which the bounds are longer and faster, the same rules are applicable to both. Many horses, especially those through whose veins strong hot blood is pulsing, fairly revel in the gallop, and if allowed to gain upon the hand, will soon extend the hand-gallop to full-gallop, and that rapid pace into a runaway. The rider must, therefore, always keep her horse well in hand, so as to be able to slacken speed should he get up too much steam. Some, impatient of restraint, will shake their heads, snatch at their bits, and yaw about, "fighting for their heads," as it is termed, and will endeavour to bore and get their heads down.

A well-trained horse, one such as a beginner should ride, will not play these pranks and will not take a dead pull at the rider's hands; on the contrary, he will stride along quite collectedly, keeping his head in its proper place, and taking just sufficient hold to make things pleasant. But horses with perfect mouths and manners are, like angels' visits, few and far between, and are eagerly sought after by those fortunate beings to whom money is no object. To be on the safe side, the rider should always be on the alert and prepared to at once apply the brake. When fairly in his stride and going comfortably, the rider, leaning slightly forward, should, with both hands on the bridle, give and take with each stroke, playing the while with the curb; she should talk cheerily to him, but the least effort on his part to gain upon the hand must be at once checked. The play of the little fingers on the curb keeps his mouth alive, prevents his hanging or boring, and makes it sensible to the rider's hand.

"Keeping a horse in hand" means that there is such a system of communication established between the rider and the quadruped that the former is mistress of the situation, and knows, almost before the horse has made up his mind what to do, what is coming. This keeping in hand is one of the secrets of fine horsemanship, and it especially suits the light-hearted mercurial sort of goer, one that is always more or less off the ground or in the air, one of those that "treads so light he scarcely prints the plain."

My impression is, despite the numerous bits devised and advertised to stop runaways, that nothing short of a long and steep hill, a steam-cultivated, stiff clay fallow, or the Bog of Allen, will stop the determined bolt of a self-willed, callous-mouthed horse. There is no use pulling at him, for the more you pull the harder he hardens his heart and his mouth. The only plan, if there be plenty of elbow room, is to let him have his wicked way a bit, then, with one mighty concentrated effort to give a sudden snatch at the bit, followed by instantly and rapidly drawing, "sawing," of the bridoon through his mouth. Above all, keep your presence of mind, and if by any good luck you can so pilot the brute as to make him face an ascent, drive him up it—if it be as steep as the roof of a house, so much the better,—plying whip and spur, till he be completely "pumped out" and dead beat. Failing a steep hill, perhaps a ploughed field may present itself, through and round which he should be ridden, in the very fullest sense of the word, till he stands still. Such a horse is utterly unfit to carry a lady, and, should she come safe and sound out of the uncomfortable ride, he had better be consigned to Tattersall's or "The Lane," to be sold "absolutely without reserve."

Worse still than the runaway professional bolter is the panic-stricken flight of a suddenly scared horse, in which abject terror reigns supreme, launching him at the top of his speed in full flight from some imaginary foe. Nature has taught him to seek safety in flight, and the frightened animal, with desperate and exhausting energy, will gallop till he drops. Professor Galvayne's system claims to be effective with runaway and nervous bolters. At Ayr that distinguished horse-tamer cured, in the space of one hour, an inveterate performer in that objectionable line, and a pair he now drives were, at one time, given to like malpractices.

Do not urge your horse suddenly from a canter into a full gallop; let him settle down to his pace gradually—steady him. Being jumped off, like a racehorse with a flying start at the fall of the flag, is very apt to make a hot, high-couraged horse run away or attempt to do so. Some horses, however, allow great liberties to be taken with them, and others none. All depends on temperament, and whether the nervous, fibrous, sanguine, or lymphatic element preponderates. And here let me remark that the fibrous temperament is the one to struggle and endure, to last the longest, and to give the maximum of ease, comfort, and satisfaction to owner and rider.

Leaping.

"Throw the broad ditch behind you; o'er the hedge

High bound, resistless; nor the deep morass refuse."

Thompson.

Though the "pleasures of the chase" are purposely excluded from this volume, the horsewoman's preliminary course of instruction would hardly be complete without a few remarks on jumping. In clearing an obstacle, a horse must to all intents and purposes go through all the motions inherent to the vices of rearing, plunging, and kicking, yet the three, when in rapid combination, are by no means difficult to accommodate one's self to. It is best to commence on a clever, steady horse—"a safe conveyance" that will go quietly at his fences, jump them without an effort, landing light as a cork, and one that will never dream of refusing. As beginners, no matter what instructors may say and protest, will invariably, for the first few leaps, till they acquire confidence, grip, and balance, ride to some extent "in the horse's mouth," they should be placed on an animal with not too sensitive a mouth, one that can go pleasantly in a plain snaffle.

Begin with something low, simple, and easy—say a three feet high gorsed hurdle, so thickly laced with the whin that daylight cannot be seen through, with a low white-painted rail some little distance from it on the take-off side. If there be a ditch between the rail and the fence, so much the better, for the more the horse spreads himself the easier it will be to the rider, the jerk or prop on landing the less severe. Some horses sail over the largest obstacle, land, and are away again without their appearing to call upon themselves for any extra exertion; they clear it in their stride. Hunters that know their business can be trotted up to five-barred gates and stiff timber, which they will clear with consummate ease; but height and width require distinct efforts, and the rear and kick in this mode of negotiating a fence are so pronounced and so sudden that they would be certain to unseat the novice.

THE LEAP.

It is easiest to sit a leap if the horse is ridden at it in a canter or, at most, in a well-collected, slow hand-gallop. The reins being held in both hands with a firm, steady hold, the horse should be ridden straight at the spot you have selected to jump. Sit straight, or, if anything out of the perpendicular, lean a little back. The run at the fence need only be a few yards. As he nears it, the forward prick of his alert ears and a certain measuring of his distance will indicate that he means "to have it," and is gathering himself for the effort. The rider should then, if she can persuade herself so to do, give him full liberty of head. Certain instructors, and horsemen in general, will prate glibly of "lifting" a horse over his fence. I have read of steeplechase riders "throwing" their horses over almost unnegotiable obstacles, but it is about as easy to upend an elephant by the tail and throw him over the garden wall as it is for any rider to "lift" his horse. Although the horse must be made to feel, as he approaches the fence, that it is utterly impossible for him to swerve from it, yet the instant he is about to rise the reins should be slacked off, to be almost immediately brought to bear again as he descends.

Irish horses are the best jumpers we have, and their excellence may justly be ascribed to the fact that, for the most part, they are ridden in the snaffle bridle. If the horse be held too light by the head he will "buck over" the obstacle, a form of jumping well calculated to jerk the beginner out of her saddle. After topping the hurdle, the horse's forehand, in his descent, will be lower than his hind quarters. Had the rider leant forward as he rose on his hind legs, the violent effort or kick of his haunches would have thrown her still further over his neck, whereas, having left the ground with a slight inclination towards the croup, the forward spring of the horse will add to that backward tendency and place her in the best possible position in which to counteract the shock received upon his forefeet reaching the ground. If the rider does not slacken the reins as the horse makes his spring, they must either be drawn through her hands or she will land right out on his neck.

I have referred to the "buck-over" system of jumping, which is very common with Irish horses. A mare of mine, well-known in days of yore at Fermoy as "Up-she-rises," would have puzzled even Mrs. Power O'Donoghue. She would come full gallop, when hounds were running, at a stone wall, pull up and crouch close under it, then, with one mighty effort, throw herself over, her hind legs landing on the other side little more than the thickness of the wall from where her forefeet had taken off. It was not a "buck," but a straight up-on-end rear, followed by a frantic kick that threatened to hurl saddle and rider half across the field. "Scrutator," in "Horses and Hounds," makes mention of an Irish horse, which would take most extraordinary leaps over gates and walls, and if going ever so fast would always check himself and take his leaps after his own fashion. "Not thinking him," writes this fine sportsman, "up to my weight, he was handed over to the second whipper-in, and treated Jack at first acquaintance to a rattling fall or two. He rode him, as he had done his other horses, pretty fast at a stiff gate, which came in his way the first day. Some of the field, not fancying it, persuaded Jack to try first, calculating upon his knocking it open, or breaking the top bar. The horse, before taking off, stopped quite short, and jerked him out of the saddle over to the other side; then raising himself on his hind legs, vaulted over upon Jack, who was lying on his back. Not being damaged, Jack picked himself up, and grinning at his friends, who were on the wrong side laughing at his fall, said, 'Never mind, gentlemen, 'tis a rum way of doing things that horse has; but no matter, we are both on the right side, and that's where you won't be just yet.'"

The standing jump is much more difficult, till the necessary balance be acquired, than the flying leap. The lower and longer the curve described, the easier to sit; but in this description of leaping, the horse, though he clears height, cannot cover much ground. His motion is like that of the Whip's horse described above, and the rider will find the effort, as he springs from his haunches, much more accentuated than in the case of the flying leap, and therefore the more difficult to sit. As, however, leaping, properly speaking, belongs to the hunting-field, I propose to deal more fully with the subject in another volume.

Dismounting.

When the novice dismounts there should, at first, be two persons to aid—one to hold the horse's head, the other to lift her from the saddle. After a very few lessons, if the lady be active and her hack a steady one, the services of the former may be dispensed with. Of course the horse is brought to full stop. Transfer the whip to the left hand, throw the right leg over to the near side of the crutch and disengage the foot from the stirrup. Let the reins fall on the neck, see that the habit skirt is quite clear of the leaping-head, turn in the saddle, place the left hand upon the right arm of the cavalier or squire, the right on the leaping-head, and half spring half glide to the ground, lighting on the balls of the feet, dropping a slight curtsey to break the jar on the frame. Retain hold of the leaping-head till safely landed.

Very few men understand the proper manner in which to exercise the duties of the cavalier servant in mounting and dismounting ladies. Many ladies not unreasonably object to be lifted off their horses almost into grooms' arms. A correspondent of the Sporting and Dramatic News mentions a contretemps to a somewhat portly lady in the Crimea, whose husband, in hoisting her up on to her saddle with more vigour than skill, sent his better half right over the horse's back sprawling on the ground. It is by no means an uncommon thing to see ladies, owing to want of lift on the part of the lifter and general clumsiness, failing to reach the saddle and slipping down again.

Having dismounted, "make much" of your horse, and give him a bit of carrot, sugar, apple, or some tid-bit. Horses are particularly fond of apples.

CHAPTER IV.

THE SIDE SADDLE.