AT THE BLACK ROCKS

AT THE BLACK ROCKS

BY REV. EDWARD A. RAND

LONDON, EDINBURGH,

DUBLIN, AND NEW YORK

THOMAS NELSON

AND SONS

CONTENTS

AT THE BLACK ROCKS.

I.

WAS HE WORTH SAVING?

"I might try," squeaked a diminutive boy, whose dark eyes had an unfortunate twist.

"Ye-s-s, Bartie," said his grandmother doubtfully, looking out of the window upon the water wrinkled by the rising wind.

"Wouldn't be much wuss," observed Bartholomew's grandfather, leaning forward in his old red arm-chair and steadily eying a failing fire as if arguing this matter with the embers. Then he added, "You could take the small boat."

"Yes," said Bart eagerly. "I could scull, you know; and if the doctor wasn't there when I got there, I could tell 'em you didn't feel well, and he might come when he could."

"That will do, if he don't put it off too long," observed the old man, shaking his head at the fire as if the two had now settled the matter between them. "Yes, you might try."

Bartie now went out to try. Very soon he wished he had not made the trial. Granny Trafton saw him step into the small boat moored by the shore, and then his wiry little arms began to work an oar in the stern of the boat. "Gran'sir Trafton," as he was called, came also to the window, and looked out upon the diminutive figure wriggling in the little boat.

"He will get back in an hour," observed Gran'sir Trafton.

"Ought to be," said Granny Trafton.

It is a wonder that Bartie ever came back at all. He was the very boy to meet with some kind of an accident. Somehow mishaps came to him readily. If any boy had a tumble, it was likely to be Bartie Trafton. If measles slyly stole into town to be caught by somebody, Bartie Trafton was sure to be one catcher. In a home that was cramped by poverty--his father at sea the greater fraction of the time, and the other fraction at home drunk--this under-sized, timid, shrinking boy seemed as continually destined for trouble as the Hudson for the sea.

"I don't amount to much," was an idea that burdened his small brain, and the community agreed with him. If the public had seen him sculling Gran'sir Trafton's small boat that day, it would have prophesied ill before very long. The public just then and there upon the river was very limited in quantity. It consisted of two fishermen wearily pulling against tide a boat-load of dried cod-fish, a boy fishing from a rock that projected boldly and heavily into the water, and several boys playing on the deck of an old schooner which was anchored off the shore, and had been reached by means of a raft.

The fishermen pulled wearily on. The boys on the schooner deck ran and shouted at their play. The young fisherman's line dangled down from the crown of the big shore-rock. The small sculler out in Gran'sir Trafton's small boat busily worked his oar. Bart did not see a black spar-buoy thrusting its big arm out of the water, held up as a kind of menace, in the very course Bart was taking. How could Bart see it? His face was turned up river, and the buoy was in the very opposite quarter, not more than twenty feet from the bow of the boat Bart was working forward with all his small amount of muscle. A person is not likely to see through the back of his head. Closer came the boat to the buoy. Did not its ugly black arm, amid the green, swirling water, tremble as if making an angry, violent threat? Who was this small boy invading the neighbourhood where the buoy reigned as if an outstretched sceptre? On sculled innocent Bartholomew, the threatening arm shaking violently in his very pathway, and suddenly--whack-k! The boat struck, threatened to upset, and did upset--Bart! He could swim. After all the unlucky falls he had had into the water, it would have been strange if he had not learned something about this element; but he had reached a place in the river where the out-going current ran with strength, and took one not landward but seaward. How long could he keep above water--that timid, shrinking face appealing for pity to every spectator? The boys on the deck of the old schooner soon saw the empty dory floating past, and they now caught also the cry for help from the pitiful face of the panting swimmer--a cry that amid their loud play they had not heard before.

"O Dick," said one of the younger boys, "there's a fellow overboard, and there's his boat! Quick!"

At this sharp warning every one looked up. Then they rushed to the schooner's rail and looked over. Yes: there was the white face in the water; there was the drifting boat.

The boy addressed as Dick was the leader of the party. His black, staring eyes, and his profusion of black, curly hair, would have attracted attention anywhere. His eyes now sparkled anew, and he tossed back his bushy curls, exclaiming,--

"Boys, to the rescue! Attention! Man the Great Emperor."

"Throw this rope," was a suggestion made by another boy, seizing a rope lying on the deck. A rope did not move Dick's imagination so powerfully as the Great Emperor. The rope was not nearly so daring as the raft, though it would have given speedy and sufficient help.

"To the rescue!" rang out Dick's voice. "Not in a rush! Ho, there! Orderly, men!"

Strutting forward with a blustering air, Dick led his rescue-band to the Great Emperor, which at the impulse of every rocking little wave thumped against the schooner's hull. The band of rescuers went down upon the raft with more of a tumble than was agreeable to Captain Dick of the Great Emperor. Dick concluded that there was too much of a crew to dexterously manage the raft in the swift voyage that must now be made. Several would-be heroes were sent back disappointed to the schooner, and they proceeded, when too late, to cast the rope which had been ignominiously spurned. It splashed the water in vain. Bartie tried to reach it; but it was like Tantalus in the fable striving to pluck the grapes beyond his grasp.

"Cast off!" Dick was now shouting excitedly, pompously. "Pull with a will for the shipwrecked mariner!" was his second order.

This meant to use two poles in poling and paddling, as might be more advantageous.

In the meantime the boy fisherman on the rock had been operating energetically though quietly. He had seen the catastrophe, and had not ceased to watch the little fellow who was struggling with the current somewhere between the schooner and the shore. Bartie had aimed to reach the shore, and the distance was not great; but just in this place the current ran with swiftness and power, and the little fellow's strength was failing him. He had given several shrieks for help, but it seemed as if he had been doing that thing all through life; and as the world outside of gran'sir and granny had not paid much attention to his appeals, would the world do it now? Bart had almost come to the conclusion that it would be easier to sink than to struggle, when he heard a noise in the water and close at hand. Was it the Great Emperor? No; its deck was still the scene of an impressive demonstration of getting ready to do something. The noise heard by Bart had been made by the boy fisherman, who, stripping off his jacket, kicking off his boots, and sending his stockings after them, had thrown himself into the water, and was making energetic headway toward Bart. It was good swimming--that of some one who had both skill and strength on his side.

"Bartie!" he shouted.

What a world of hope opened before Bartie at the sound of that voice!

"Here! here! Put your hands on my shoulders, not round my neck, you know. There! that is it. Now swim. We'll fetch her."

Fetch what? It was a pretty difficult thing to say definitely what that indefinite "her" might mean. The current was still strong. Bart's rescuer, if alone, could have gained the shore again; but could he bring the rescued? Bart's face, pitiful and pale, projected just above the water, and as his wet hair fell back upon his forehead his countenance looked like that of a half-drowned kitten.

A third party on the river, that of the fishermen in their cod-laden boat moving slowly up river and hugging the shore for the sake of help from the eddies, had now become conscious that something was going on.

"What's that a-hollerin'?" asked one of the men, Dan Eaton, reversing his head.

"Trouble enough!" exclaimed Bill Bagley, who had also taken a look ahead. "Pull, Bill!"

"Put for them two boys, Dan! one is a-helpin' t'other."

The boat began to advance as if the dead cod-fish had become live ones and were lending their strength to the oarsmen.

"Good!" thought the rescuer in the water, who saw between him and the far-off, level, misty sky-line a boat and the backs of two fishermen. "Hold on there!" he said encouragingly to Bartie; "there's a boat coming!"

The help did not arrive any too soon. Bartie's hands were resting lightly on his rescuer's shoulders, and he was arguing if he could not throw his arms around the neck of his beloved object, whether it might not be well to relinquish his feeble, tired hold altogether, and drop back into the soft, yielding depths of the water all about him; such an easy bed to lie down in! Life had given him so many hard berths. This seemed a relief.

"Ho, there you are!" shouted Dan, as the boat came up. He seized Bartie, while Bill Bagley gripped the other boy, and both Bartie and his companion were hauled into the boat, rather roughly, and somewhat after the fashion of cod-fish, but effectually.

"Now, Dan, let us pull for that cove and land our cargo!" said Bill. "You boys can walk home? We have got to go to the other side and take our fish to town."

"Oh yes," said the rescuer.

"I--I--can--walk!" exclaimed the shivering Bartie.

"Ah, youngster, you came pretty near not walking ag'in if it hadn't been for t'other chap."

This made Bartie feel at first very sober, and then he looked very grateful as he turned toward his rescuers and said,--

"I--thank--you all. I--I--I'll do as--much for you--some time."

"Will ye?" replied Bill Bagley with a grin. "Really, I hope we shan't be in that fix where you'll have to."

"See there!" exclaimed Dan. "There's the boat adrift!"

The Trafton boat was leisurely floating down the stream. Bart had forgotten all about this craft. A frightened look shadowed his face.

"Don't you worry, Johnny!" said Bill Bagley kindly. "We will land you, and then go a'ter your craft."

"But I promised gran'sir to go for the doctor."

"Dr. Peters?"

"Yes."

"Wall, Dan and I are goin' near the old man's, and we'll send him over.--Won't we, Dan?"

"And I'll bring your boat up to your landing," said his young rescuer to Bart. "So you go right home and get warm and don't worry."

A thankful look, like sunshine out of a dark cloud, broke out of Bart's black eyes, and he shrank closer to the sympathetic breast on which he leaned.

"I'll do as much for you," he whispered to the boy fisherman.

"That's all right, Bartie," replied his rescuer.

"See here!" now inquired Dan. "What are those spoonies up to? Where are they a-goin', I wonder, on that raft? To Afriky?"

"Guess that craft's got to be picked up too. She's a-makin' for the sea in spite of all their polin'," said Bill.

The Great Emperor was indeed moving seaward. Captain Dick was frantically ordering his crew to "pull her round;" but like sovereigns generally, the Great Emperor had a mind of its own, and would not be "pulled round." Deliberately the raft was making headway for the open sea, and possibly "Afriky." It might be a conspiracy on the part of wind and tide to aid in this wilful attempt of the raft; but if a conspiracy, it was no secret. The tide was openly pressing against the raft with its broad blue shoulders, and the wind openly blew against the boys, as if they were so much canvas spread for its filling.

"What you up to, fellers?" shouted Dick to Dab and John Richards, who managed one of the poles. "Bring her round and head her for the shore!"

"We can't," said John pettishly.

"Can't!" replied Dick in scorn. "Why can't you? Tell me! Then we will spend the night on the sea.-- You pull, Jimmy."

"Can't!" said Jimmy Davis nervously. "She--she--won't turn--and--"

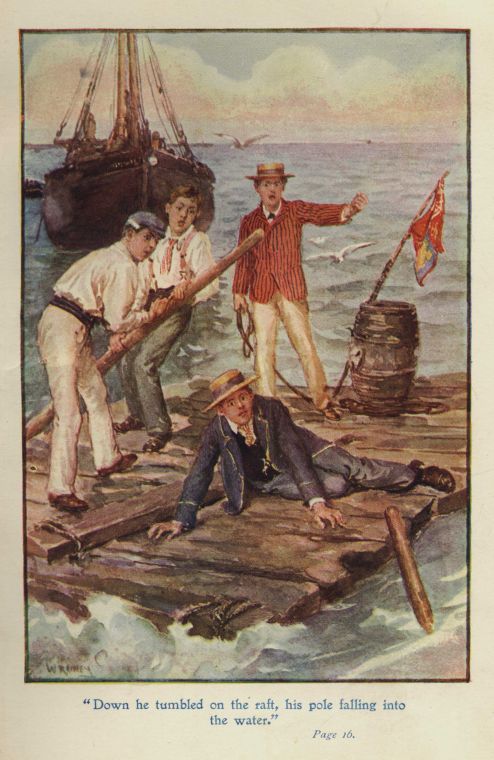

Here his pole slipped out of its hole and down he tumbled on the raft, his pole falling into the water.

"Oh dear!" shrieked Dick. "What a set! There goes that oar! Reach after it, Dab!"

Dab already was beating the water furiously with his pole in his efforts to reach that "oar" now adrift. It was all in vain. The conspiracy to take them all to sea and there let them spend the chilly night had spread to the very equipments of the Great Emperor.

"Catch me on a raft ag'in!" whimpered John Richards.

"Catch me on one with you!" replied Dick fiercely. "Might have got that boy if you had pulled, and now those other folks have got him."

"'Those other folks' are coming after us!" observed Dab Richards.

"Oh dear!" groaned the humiliated Dick. "Make believe pull up river."

"I won't!" said John Richards.

"Pull so that they may think that we don't need them. Now!" urged Dick.

"I won't!" declared Dab.

Jimmy Davis also was going to say, "I won't;" but he remembered that his pole was in the water, and refrained. He looked rebellious, though he said nothing.

There was now not only a conspiracy among the elements, but a mutiny among the crew. Dick sulked.

"Let her drift!" he said. "I don't care!"

"She won't drift long!" remarked Dab sarcastically. "The Great Emperor, that started to pick up somebody, is now going to be picked up by somebody."

Yes, the fishermen were pulling out from the shore. They picked up the boat, attached it to their own craft, and then laboriously rowed for the vessel in the hands of conspirators without and mutineers within.

"Where you chaps bound?" shouted Dan.

"Bound for the bottom of the sea," said Dick grimly.

"We'll stave that off," said Bill. "Here, take this rope! Now, we must try to git you ashore."

It was rather a queer tug-boat that did the towing---a fisherman's dory in which, sandwich fashion, alternated piles of codfish and oarsmen rowing; Bill, Dan, and Bart's rescuer. It was a singular fleet also that was towed ashore--the Great Emperor and Gran'sir Trafton's boat.

"Who is that boy rowing with those fishermen?" wondered Dick. "Can it be--"

Then he concluded it could not be.

Again he guessed. "Must be--"

Then he declared it was somebody else.

Finally, when this strange fleet had been beached, Dick shouted out, "That you, Dave Fletcher?"

"Nobody else," answered Bart's rescuer, advancing. "I have been nodding to you, but I guess you didn't know who it was; and I don't wonder--the way I look after my bath. Haven't got on the whole of my rig yet. How is Dick Pray?"

The two shook hands warmly.

"I haven't seen you for some time, Dave. I have been from home a while, going to school and so on. I am stopping at my cousin's, Sam Whittles, just now."

"And I have been here only a few days, visiting at my uncle's, Ferguson Berry."

"All right. We will see each other again then. I'll leave the old raft here and come for it when the tide is going up river."

"And I am going to get the doctor. Oh no, come to think of it, these men will get him for that little fellow's folks--the one we picked up, you know."

"We? You, rather. You did first-rate. Well, who was that little shaver?"

"I heard somebody call him Bartie. That's for Bartholomew, I guess."

"Oh, it's 'Mew,'" explained Dab. "Bartholo*mew*; and they say 'Mew' for short--'Little Mew.'"

"His face looked like a kitten's there in the water," said Dick, "and he mewed pitifully. I've heard of him. Sort of a slim thing. Well, may sound sort of heartless, but I guess some folks would say he is hardly worth the saving. Oh, you're off, are you?"

"Yes," said one of the two fishermen who were now pushing their boat off from shore. "We must get to town with our fish as soon as we can."

"Well, friends, I am much obliged to you," said Dick Pray.

"So am I! so am I!" said several others.

"Count me in too," exclaimed Dave Fletcher. "Might not have been here without you.--Give 'em three cheers, boys!"

Amid the huzzahs echoing over the waters, the fishermen, smiling and bowing, rowed off.

"Many thanks, boys, if you will help me to turn Bart's boat over and get the water out. I must row it up to the rock where the rest of my clothes are, and then we might all go along together. We can pick up the fellows on the schooner."

The remnant of Captain Dick's crew on board the schooner gladly abandoned it when Gran'sir Trafton's boat came along, and all journeyed in company up the river.

And where was Little Mew? He went home only to be scolded by gran'sir because he had not brought the doctor, and because he had somehow got into the water somewhere. Granny was not at home, and Little Mew dared not tell the whole story. He was sent upstairs to change his clothes and stay there till granny got home.

"Gran'sir don't know I haven't got another shift," whined Little Mew. "Got to get these wet things off, anyhow."

He removed them and then crept into bed. It was dark when granny returned.

From the window at the head of his bed Bartie watched the sun go down, and then he saw the white stars come into the sky.

About that time the evening breeze began to breathe heavily; and was that the reason why the stars, blossom-like, opened their fair, delicate petals, even as they say the wind-flowers of spring open when the wind begins to blow?

"They don't seem to amount to much--just like me," thought Bartie; and having thus come into harmony with the world's opinion of himself, he closed his eyes, like an anemone shutting its petals, and went to sleep.

Don't stars amount to much? They would be missed if, some night, people looking up should learn that they had gone for ever.

And granny coming home, having learned elsewhere the full story of Little Mew's exposure to an awful peril, went upstairs, and, candle in hand, looked down on the motherless child in bed fast asleep.

"Poor little boy!" she murmured. "I should miss him if he was gone. Yes, I should terribly."

She wiped her eyes, and then tucked up Bartie for the night.

II.

CAUGHT ON THE BAR.

Dave Fletcher and Dick Pray were boys who had grown up in the same town, but from the same soil had come two very different productions. They were unlike in their personal appearance. Dick Pray would come down the street throwing his head to right and left, scattering sharp, eager glances from his restless black eyes, and swinging his hands.

"Somebody is coming," people would be very likely to say.

Dave Fletcher had a quiet, unobtrusive, straight-forward way of walking. Dick was quite a handsome youth; but the person that Dave Fletcher saw in the glass was ordinary in feature, with pleasant, honest eyes of blue, and hair--was it brown or black?

Dave sometimes wished it were browner or blacker, and not "a go-between," as he had told his mother.

Dave and Dick were not as yet trying to make their own way; but they were between fifteen and sixteen, and knew that they must soon be stirring for themselves.

They had already begun to intimate how they would stir in after life.

Dave had a quiet, resolute way. There was no pretence or bluster in his methods. In a modest but manly fashion he went ahead and did the thing while Dick was talking about it, and perhaps magnifying its difficulty, that inferentially his courage and pluck in attempting it might be magnified. Dick's way of strutting down-street illustrated his methods and manners. There was a great deal of bluster in him. Nobody was more daring than he in his purposes, but for the quiet doing of the thing that Dick dared, Dave was the boy. Somehow Dick had received the idea that the world is to be carried by a display of strength rather than its actual use; that men must be impressed by brag and noise. Thus overpowered by a sensational manifestation they would be plastic to your hands, whatever you might wish to mould them into. Dick did not hesitate to attack any fort, scale any mountain, or cross any sea--with his tongue. When it came to the using of some other kind of motive power--legs for instance--he might be readily outstripped by another. Among the boys at Shipton he had made quite a stir at first. His bluster and brag made a sensation, until the boys began to find out that it was often wind and not substance in Dick's bragging; and they were now estimating him at his true value. Dave Fletcher was little known to any of them save small Bartholomew Trafton; but Dave's modest, efficient style of action they had seen in the saving of Little Mew, and they were destined to witness it in another impending catastrophe.

"Uncle Ferguson, who owns that old schooner off in the river?" asked Dave one day, as he was eating his way through a generous pile of Aunt Nancy's fritters. It was the craft to which had been tied the Great Emperor.

"Why, David?"

"Because some of us boys want to go there and stay a night or two. We take our provisions with us, and each one a couple of blankets, and so on, and we can be as comfortable on the schooner as can be. Would you and Aunt Nancy mind if we went?"

"Mind if you went? No; I don't know as I do.--What do you say, Nancy?"

Uncle Ferguson was a middle-aged man, with ruddy complexion and two blue eyes that almost shut and then twinkled like stars when he looked at you.

Aunt Nancy was a plain, sober woman, with sharp, thin features, and bleached eyes of blue.

"Don't know as I mind," declared Aunt Nancy. "If you don't git into the water and drown, you know."

"Oh, that's all right," said the nephew.

"Only you must see the owner of the schooner," advised the uncle.

"The owner?"

"Yes; Squire Sylvester. He is very particular about anything he owns."

"Oh, I didn't know the thing had an owner," said Dave, laughing. "It seems to lie there in the stream doing nothing. The boys didn't say anything about an owner."

"Squire Sylvester is very particular," asserted Uncle Ferguson. "He got his property hard, and looks after it."

"Yes, he is very pertickerler," added Aunt Nancy.

"Well, we will see him by all means. We boys--"

"Didn't think; that is it, David. Now, when I was a boy we always asked about things," said Uncle Ferguson.

"Well, husband, boys is boys, in them days and these days. I remember your mother used to say her five boys used to cut up and--"

"Well," replied Uncle Ferguson, rising from the table, "this won't feed the cows; and I must be a-goin'. I would see Sylvester, David."

"All right, uncle."

Dave announced his intention to Dick half-an-hour later.

"Well, go, if you want to. We fellows were not going to say anything to anybody. Who would be the wiser? The thing lies in the river, knocking around in the tide, and seems to say, 'Come and use me, anybody that wants to.'"

"If we owned the schooner we would prefer to have it asked for, if she was going to be turned into a boarding-house for a day or two."

"I suppose it would be safer to ask. If we didn't ask, and the owner should come down the river sailing and see us, wouldn't there be music?"

"We will save the music, Dick. I will just ask him."

As Dave neared Squire Sylvester's office he could see that individual through the window. He was a man about fifty years old, his features expressing much force of character, his sharp brown eyes looking very intently at any one with whom he might be conversing. Dave hesitated at the door a moment, and then summoning courage he lifted the latch of the office door and entered.

"Good-day, sir."

The squire nodded his head abruptly and then sharply eyed the boy before him.

"We boys, sir--"

"Who are you?" asked the squire curtly.

"David Fletcher. I am visiting at my uncle's, Ferguson Berry."

"Humph! Yes, I know him."

"We boys, sir, wanted to know if you would let us--"

"What boys?"

"Oh, Jimmy Davis, John Richards--"

"I know those."

"Dick Pray---"

"Pray?"

"He is visiting his cousin, Samuel Whittles."

"Oh yes; I've seen him in the post-office. Curly-haired boy; struts as if he owned all Shipton."

"Just so."

"Well?"

"John Richards's brother--that is all. We want to know if you will let us stay out in the old schooner for a while. We will try to be particular and not harm the vessel."

"How long shall you want to be gone?"

"Oh, two or three days and nights."

"Humph! Well, you can't have any fire on board. Got a boat?"

"Yes, sir."

"Of course, for you can't wade out to her. Put it out there on purpose so folks couldn't paddle and wade out to her, such as tramps, you know. Well, if you have a boat you can cook on shore."

"Yes, sir."

"You may have a lantern at night. No objection to that."

"We will remember."

"All right, then."

"Oh, thank you! Good-day, sir."

"Good-day."

The squire's sharp brown eyes followed Dave as he went out of the door, and then watched him as he tripped down the street laughing and whistling.

"Like all young chaps--full of fun. Rather like that boy."

Dave announced the result of the conference to several boys anxiously waiting for him round the corner.

"Got it?" asked Dick Pray.

"Yes; tell us what he said," inquired Dab Richards.

The boys pressed eagerly up to Dave, who announced the successful issue of his application. A burden of painful anxiety dropped from each pair of shoulders, and the boys separated to collect their "traps," promising to meet at Long Wharf, where a boat awaited them. Did ever any craft make a happier, more successful voyage, when the boat received its load two hours later and was then pushed off?

"Everything splendid, boys!" said Dick. "Won't we have a time while we are gone, and won't we come back in triumph?"

The return! How little any of the party anticipated the kind of return that would end their adventure!

"There's the schooner!" shouted Dave. "I can read her name on the stern--RELENTLESS. Letters somewhat dim."

"She is anchored good," said Dab Richards. "Got her cable out."

"Anchor at the bottom of it, I suppose," conjectured Jimmy Davis.

"We will find out, boys, won't we? We will just hoist her a bit, as the sailors say, and see what she carries," said Dick, in a low tone.

"Nonsense!" said Dave. "Sylvester has our word for good behaviour."

"Oh, don't you worry!" said Dick, in a jesting tone. "Let's see! Shall we make our boat fast round there? Where shall it be?"

The best mooring was found for the boat, and then a ladder with hooks on one end was attached to the vessel's rail, and up sprang the boys eagerly.

The Relentless was an old fishing-schooner. She had been stripped of her canvas, and portions of her rigging had been removed. There were the masts, though, still to suggest those trips to distant fishing-grounds, when the winds had filled the canvas and sent the Relentless like an arrow shot from one curving billow to another. There was the galley, empty now of its stove, and showing to any investigator only a rusty pan in one corner; but the wind humming round its bit of rusty funnel told a story of many a savoury dish cooked for a hardy, hungry crew. And the little cabin, so still now, save when a hungry rat softly scampered across its floor, had been a good corner of retreat to many when heavy seas wet the deck on stormy nights and sent the spray flying up into the rigging.

The boys transferred their cargo of bedding and eatables to the deck, and then scattered to ramble through the cabin or descend into the dark, musty hold. They came together again, and lugged their baggage into the cabin, save the dishes and eatables, which were stowed away on shelves.

"This is just splendid, Dick!" declared Dave, leaning over the vessel's rail. "It is going to sea without having the fuss of it."

"That's so, Dave. You don't have any sea-sickness, any blistering your hands with handling ropes, any taking in sail--"

"Oh, it's huge, Dick. Now you want to divide up the work."

"Not going to have any; all going to have a good time."

"But who's going to cook, and bring water, and--"

"Oh, I see! Forgot that."

A division of work was finally pronounced sensible. Dave became "cook," Jimmy Davis was elected "water-boy," Dick took charge of the sleeping arrangements, and the brothers Richards were constituted table-waiters and dish-washers--"without pay," Dave prudently added. All that day, up to twilight, life in the old fishing-schooner was smooth and happy as the music of a marriage-bell. Dave's cooking was adjudged "splendid," and between meals there were spells of story-telling, of games like hide-and-seek about the ancient hull, and of fishing from the deck, though there sometimes seemed to be more fishermen than fish.

At twilight most of the boys were seated in the stern of the vessel, looking out to sea and watching the light fade out of the heavens and the warm sunset glow steal away from the waters.

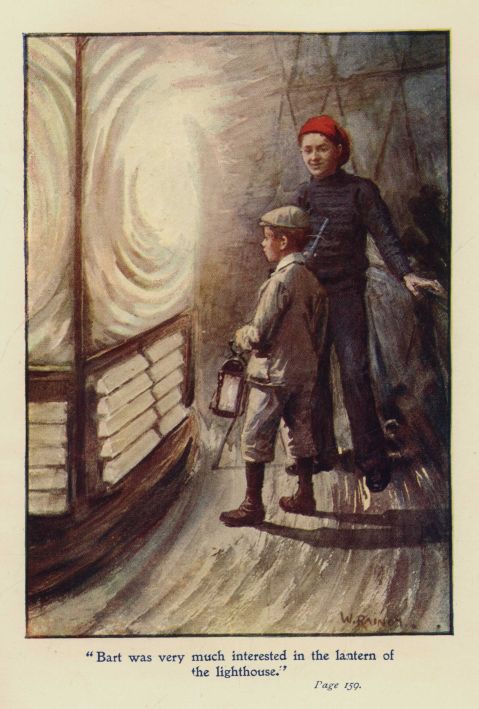

"There's the light starting up in the lighthouse near the bar," said Dab Richards.

Yes, Toby Tolman, keeper of the light at the harbour's mouth, and not far from a dangerous bar, ever changing and yet never going, had kindled a star in the tall lantern as the western clouds dropped their gay extinguisher on the sun's dwindling candle. Between the boys and the outside, dusky surface of ocean water stretched a line of whitest foam, where the waves broke on the bar.

"Getting chilly," said Dave. "Hadn't we better go into the cabin and light our lantern?"

"Guess Dick is looking after that," said Jimmy.

No; Dick was looking after--meddling, rather, with something else. He had whispered to John Richards, "Come here, John," and then led him to the bow of the vessel.

"See here, Johnny."

"What is it, Dick?"

"Wouldn't it be nice to see this old ark move?"

"Move! what for?"

"Oh, I've got tired of seeing it in one place."

"Why, what do you mean? How?"

"Why, just have it go on a little voyage, you know."

"Voyage?"

"You booby, can't you understand?"

"Understand? No," replied John good-naturedly. "Don't see how we can have a voyage without sails, and the masts are bare as bean-poles when there ain't any beans on 'em."

"Oh, you're thick-headed. Don't you see this anchor?"

"Don't see any. I suppose there is one somewhere--covered up, you know, down on the bed of the river."

"Only water covers it, and it could be raised, and we could have a sail without any sails."

"Come on!" said John, who was the very boy for any kind of an adventure. "But," he prudently added, "how could we stop?"

"Drop the anchor again. Why, we could stop any time."

"So we could."

"We could sail, say a hundred feet to-night--tide would drift us down--and then we could drop anchor; and to-morrow, when the tide ran up river, we could sail back again and drop anchor, just where we were before."

"We could keep a-going, couldn't we, Dickie?"

"Certainly. I don't know but we could go quarter of a mile and then back again. We should have, of course, to go with the tide; but the anchor would regulate us."

"So we could. Just the thing. Let's try it. Shall I tell the fellers?"

"No; let's surprise 'em."

"But they'll hear us."

"No; they are quarrelling about something, and they won't notice anything we do here."

"But how can you manage the anchor?"

"Raise it."

"But how raise it?"

"Johnny, I believe you have lost your mind since coming here. What is this I have got my hand on?"

"The capstan."

Dick here laid his hand on a battered old capstan, around which how many hardy seamen had tramped singing "Reuben Ranzo" or some other roaring song of the sea.

"Don't you know how this works?"

"Not exactly."

"I will tell you. You see this bar?"

Dick with his foot kicked a battered but stout bar lying at the foot of the capstan.

"There! one end of the cable to which the anchor is hitched goes round this capstan, you see. Now, if I stick this bar into that hole in the capstan and shove her round--I mean the bar--the capstan will go round too, and that will wind up that cable and draw on the anchor. Don't you see?"

"Yes, I see."

"Well, now we are ready. I will sing something like real sailors."

"The boys will hear us."

"No: they are fighting away; they won't notice."

It was a tongue-fight, but that may be as absorbing as a fist-fight.

"You know 'Reuben Ranzo'?"

"Yes."

"Well, sing in a whisper and pull."

The bar was inserted into the capstan, and the boys, as they shoved on the bar, sang softly,--

"O poor Reuben Ranzo!Ranzo, boys, Ranzo!"

"That's the chorus, Johnny. Sing the other part. Shove hard but sing easy."

"Oh, Reuben was no sailor.Chorus--O poor Reuben Ranzo!Ranzo, boys, Ranzo!O poor Reuben Ranzo!Ranzo, boys, Ranzo!"

"Sing another verse, Johnny. That shove just took up the slack-line, and the next will pull on the anchor. Hun-now, Johnny! You're a real good sailor. Sing easy, but shove."

"He shipped on board of a whaler.Chorus--O poor Reuben Ranzo!Ranzo, boys, Ranzo!O poor Reuben Ranzo!Ranzo, boys, Ranzo!"

The last tug at the bar came hard, but the boys took it as an encouraging sign that the anchor too was coming. They were not mistaken. Another minute, and Johnny eagerly exclaimed,--

"Dick, I do believe she's going!"

"Good! That's so. I knew 'Reuben Ranzo' would bring her."

Yes, the Relentless had relented before the fascinating persuasion of "Reuben Ranzo," and without a murmur of resistance was softly slipping through the dark sea water.

"Can you stop her any time, Dick?" asked Johnny in tones a bit alarmed.

"Easy. Just let the anchor slip back again, you know."

"Shan't we tell the boys?"

"Wait a moment. We want to surprise 'em. They'll find it out pretty soon."

The boys at the stern had been discussing a subject so eagerly that every one had lost his temper, and when that is lost it may not be found again in a moment. It was like starting the Relentless--a thing quite easily done; but as for stopping her--however, I will not anticipate. The boys were quarrelling about a light on shore, and wondering why that illumination was started so early, when it did not seem dark enough for a home light. In the course of the discussion a second light, not far from the first, came into view. Over this the controversy waxed hotter than ever, and led to much being said of which all felt heartily ashamed.

No one heard the creak of the capstan-bar at the bow or the devoted wooing of the Relentless by the fascinating "Reuben Ranzo."

"That's funny," said Dave, after a while. "One of those lights has gone. They have been approaching one another, I have noticed. Look here, fellers: I believe this old elephant is moving!"

"She is," exclaimed Jimmy Davis.

They all turned and looked toward the bow. The figures there were growing dim in the thickening twilight, but they could see Dick and Johnny waving their hats, and of course they could plainly hear them shout, "Hurrah! hurrah!"

"What's the matter?" cried Dave, rushing across the deck.

"Having a sail," said Dick.

"And without a sail too," cried Johnny triumphantly.

"What do you mean?" asked Dab.

"Why, we just hoisted the anchor, and the tide is taking us along," replied Dick. The party at the stern did not know how to take this announcement.

"But," said Dave, advancing toward the capstan, and remembering his promise to Squire Sylvester that he would be "particular," "we are adrift, man!"

"Oh, we can stop any time--just drop the anchor--and the next tide will drift us back where we were before."

"Y-e-s," said Dave, but reluctantly, "if we don't get in water too deep for our anchor. I like fun, Dick, but--"

"Oh, well," replied Dick angrily, "we will stop her now if you think we need to be so fussy.--Just let her go, Johnny."

Johnny, however, did not understand how to "let her go." It seemed to him and the others as if "she" were already going.

"Oh, well, I can show you, if you all are ignorant," said Dick confidently. "Just shove on this bar--help, won't you?--and then knock up that ratchet that keeps the capstan from slipping back--there!"

The weight of the anchor now drew on the capstan, and round it spun, creaking and groaning, liberating all the cable that had been wound upon it; but when every inch of cable had been paid out, what then?

"There! The anchor must be on bottom, and she holds!" shouted Dick in triumph.

"No--she--don't," replied Dab. "We are in deep water, and adrift."

"Can't be," asserted Dick. "All that cable paid out!"

Dick leaned over the vessel's rail and tried to pierce the shadows on the water and see if he could detect any movement. "Don't--see--anything that looks like moving, boys. Surely the anchor holds her," he said, in a very subdued way.

"Dick, see that rock on the shore?" asked Dave.

A ledge, big, shadowy, could be made out.

"Now, boys, keep your eyes on that two or three minutes and see if we stay abreast of it," was Dave's proposed test.

Five pairs of eyes were strained, watching the ledge; but if there had been five hundred, they would not have seen any proof that the vessel was stationary.

The ledge was stationary, but the Relentless--

"Well," said Dick, scratching his head, "I don't think we need worry. We--we--"

"Can drift," said Dab scornfully.

"It is of no use to cry over spilled milk," said Dave, in a tone meant to assure others. "Let's make the best of it, now it's done, and get some fun out of it if we can. All aboard for--Patagonia!"

"Good for you," whispered Dick. "The others are chicken-hearted. We shall come out of it all right; though I wish the schooner's rudder worked, and we might steer her."

The rudder was damaged and would not work.

"Say, boys, we might tow her into shallow water!" suggested Dave. "Come on, come on! Let's have some fun. And see--there's the moon!"

Yes, there was a moon rising above the eastern waters, shooting a long, tremulous arrow of light across the sea. The boys' spirits rose with the moon, and as the light strengthened, their surroundings--the harbour, the lighthouse near the bar, the shores on either hand--were not so indistinct.

"Not so bad," said Dick in a low tone to Dab. "There's our boat, you know. We can get into that and let this old wreck go. We can get ashore. We will have a lot of fun out of this."

The situation was delightful, as Dick continued to paint its attractions. They could have a "lot of fun" out of the schooner, and at the same time abandon the source of it when that failed them. Dave talked differently.

"Come, boys, we must try to get the old hulk ashore," he said. "I believe in staying by this piece of property long as we got permission to use it; but we will make the best of our situation. All hands into the boat to tow the schooner into shallow water!"

The boys responded with a happy shout, and climbed over the vessel's side, descending by the ladder that still clung to the rail.

"What have we got to tow with?" asked Jimmy Davis.

"That is a conundrum!" replied Dave. "Didn't think of that!"

"May find something on the deck," suggested Dick.

A hunt was made, but no rope could be found.

"Boys, we have got to tow with the boat's painter; it's all we have got," said Dave, in a disgusted tone. This rope was about ten feet long. It was attached to the schooner's bow, and how those small arms did strain on the oars and strive to coax the Relentless into shoal water!

"Give us a sailor's song, Dick," said Jimmy Davis.

"I will, boys, when I get my breath," replied Dick, puffing after his late efforts and wiping the sweat from his brow. "I'll start 'Reuben Ranzo.'"

The boys sang with a will, and their voices made a fine chorus.

"Reuben" had been able to coax the schooner away from her moorings, but he could not win her back.

True to her name, she obstinately drifted on.

"Don't you know anything else?" inquired Dave.

"I know 'Haul the Bow-line.'"

"Give us that, Dick."

"I'll start you on the words, boys,--

'Haul the bow-line, Kitty is my darling;Haul the bow-line, the bow-line haul.'

Sing and pull, boys."

The boys sang and the boys pulled, and there was a fierce straining on that bow-line; but no soft words about "Kitty" had any effect on the Relentless. It seemed as if this obdurate creature were moved by an ugly jealousy of "Kitty," and drifted on and on.

"It's of no use!" declared Dick. "I move we untie our rope and go ashore and let the old thing go. We have done what we could to get ashore."

He did not say that he had done what he could to get the Relentless adrift, and had fully succeeded. Dave did not twit him with the fact, but he was not ready to abandon the schooner.

Some of the boys murmured regrets about their "things." They did not want to forsake these.

"Well, boys," said Dick, with a boastful air, "I'll get you out of the scrape somehow. We might go on deck again, and hold a council of war and talk the situation over."

Any change was welcomed, and the boys scrambled on deck again. Dick was the last of the climbing column.

"Hand that painter up here and I'll make it fast," said Dave. "Then come up and we will talk matters over."

"Oh!" said Dick, who was half-way up the ladder, "I forgot to bring that rope up."

He descended the ladder and reached out his foot to touch the boat, but he could not find it! When he had left the boat, a minute ago, he gave it unintentionally a parting kick, and--and--alas! The boat was now too far from the schooner's side to be reached by Dick's foot.

"Get something!" he gasped. "Bring a--pole--and--get that boat!"

The boys scattered in every direction to find a--they did not know what, that in some way they might reach after and capture that escaping boat. Their excitement was intense but fruitless. There were now two vessels adrift--a schooner and a dory--serenely floating in the still but strong current, steadily moving seaward, and the moonlight that had been welcomed only revealed to them more plainly the mortifying situation of the party.

"Ridiculous!" exclaimed Dick.

Most of the boys looked very sober. Dave put his hands in his pockets and whistled.

"Well, boys, don't you worry! I'll get you out of this in good fashion yet," cried Dick. "We can't go far to sea, and then the tide will bring us back again in the morning."

"Far to sea!" said Dab mockingly. "There's the lighthouse on the left, and it looks to me as if we should hit the bar!"

The bar! The boys started. At the mouth of the river the sand brought down from the yielding shores would accumulate, and it formed a bar whose size and shape would annually change, but the obstacle itself never disappeared. There it stretched in the navigator's way, seriously narrowing the channel; and of how many catastrophes that "bar" had been the occasion! The breakers above were soft and white, and the sand below was yielding and crumbling; and yet just there how many vessels had been tripped up by that foot of sand thrust out into the harbour! The boys laughed and tried to be jolly, but no one liked the situation. It was a very picturesque scene,--the moonlight silvering the sea, the calmly-moving schooner and boat, that lighthouse like a tall, stately candlestick lifting its quiet light; but, for all that, there was the bar! Either the night-wind was growing very chilly, or the boys shivered for another reason.

"Don't worry, fellows," said Dick, putting as much courage as possible into his voice. "When this old thing hits, you see, we shan't drift right on to the bar, but our anchor will catch somewhere on this side. That will hold us. I can swim, and I'll just drop into the sea and make for the light and get Toby Tolman's boat, and come and bring you off."

He then proceeded to hum "Reuben Ranzo;" but nobody liked to sing it, and Dick executed a solo for this unappreciative audience.

"How--how deep is the water inside the bar?" said chattering Jimmy Davis. He felt the cold night-air, and he shook as if he had an ague fit.

"Pretty deep," solemnly remarked Dab Richards.

The musical hum by the famous soloist, Dick Pray, ceased; only the breakers on the bar made their music.

Dick began to doubt seriously the advisability of dropping into that deep gulf reputed to be inside the bar. It was now not very far to the lighthouse, and the surf on the bar whitened in the moonlight and fell in a hushed, drowsy monotone. People by the shore may be hushed by this lullaby of the ocean, but to those boys there was nothing drowsy in its sound; it was very startling.

"I--I--I--" said Jimmy.

"What is it, Jimmy?" asked Dave.

Jimmy did feel like wishing aloud that he could be at home, but he concluded to say nothing about it. Steadily did the Relentless drift toward that snow-line in the dark sea.

"Almost there!" cried Dave.

"May strike any moment!" shouted Dab.

Yes, nearer, nearer, nearer, came the Relentless to that foaming bar. The boat had already arrived there, and Dave saw it resting quietly on its sandy bed. Did he notice a glistening strip of sand beyond the surf? He had heard some one in Shipton say that at very low tide there was no water on portions of the bar. This fact set him to thinking about his possible action. It now seemed to him as if the distance between the stern of the vessel and the bar could not be more than a hundred feet. The bow of the vessel pointed up river. She was going "stern on." How would it strike--forcibly, easily?

"Ninety feet now!" thought Dave. "Will the shock upset her, pitch us out, or what?"

Sixty feet now!

"The bar looks sort of ugly!" remarked Johnny Richards.

Thirty feet now!

"Wish I was in bed!" thought Jimmy Davis.

Twenty feet now!

Had the schooner halted? The boys clustered in the bow and looked anxiously over to the bar.

"Boys, she holds, I do believe," said Dave.

"All right!" shouted Dick--"all right! The anchor holds!"

It did seem an innocent, all-right situation: just the quiet sea, the musically-rolling surf along the bar, the stately lighthouse at the left, and that schooner quietly halting in the harbour.

"Now, boys," exclaimed Dick, "we can--"

"I thought you were going to swim to the lighthouse?" observed Dab.

"Oh, that won't be necessary now," replied Dick. "We are just masters of the situation. The moment the tide turns we can weigh anchor and drift back again just as easy! Be in our old quarters by morning, and nobody know the difference. Old Sylvester himself might come down the river, and he would find everything all right. Ha! ha!"

Dick's confidence was contagious, and when he proposed "Haul the Bow-line," his companions sang with him, and sang with a will. How the notes echoed over the sea! Such a queer place to be singing in!

"Mr. Toby Tolman," said Dick, facing the lighthouse, "we propose to wake you up! Let him have a rouser. Give him 'Reuben Ranzo!'"

While they were administering a "rouser" to Mr. Toby Tolman, somebody at the stern was dropping into the sea. He had stripped himself for his swim, and now struck out boldly for the bar. Reaching its uncovered sands he ran along to the boat, lying on the channel side of the bar and not that of the lighthouse, leaped into the boat, and, shoving off, rowed round to the bow of the schooner. There was a pause in the singing, and Dick Pray was saying, "This place makes you think of mermen," when Dab Richards, looking over the vessel's side, said, "Ugh! if there isn't one now!"

"Where--where?" asked Johnny.

"Ship ahoy!" shouted Dave from the boat. "How many days out? Where you bound? Short of provisions?"

"Three cheers for this shipwrecked mariner just arrived!" cried Dab. And the hurrahs went up triumphantly in the moonlight. Dave threw up to the boys the much-desired painter, and the runaway boat was securely fastened.

"There, Dave!" said Dick, as he welcomed on deck the merman: "I was just going after that thing myself, just thinking of jumping into the water, but you got ahead of me. Somehow, I hate to leave this old craft."

"I expect," said Dab Richards, a boy with short, stubby black hair and blue eyes, and lips that easily twisted in scorn, "we shall have such hard work to get Dick away from this concern that we shall have to bring a police-officer, arrest, and lug him off that way."

"Shouldn't wonder," replied Dick. "Couldn't be persuaded to abandon this dear old tub."

"Well, boys, I'm going to the lighthouse as soon as I'm dressed," said Dave.

There was a hubbub of inquiries and comments.

"What for?" asked Dick. "Ain't we all right?"

"I hope so; but I want to keep all right. I want to ask the light-keeper--"

"But all we have got to do is to pull up anchor when the tide comes, and drift back."

"Oh yes; we can drift back, but where? We can't steer the schooner. We don't know what currents may lay hold of her and take her where we don't want to go. There are some rocks with an ugly name."

"'Sharks' Fins!'" said Jimmy. "Booh!"

"What if we ran on to them?" said Dave. "We had better go and ask Toby Tolman's opinion. He may suggest something--tell us of some good way to get out of this scrape. He knows the harbour, the currents, the tides, and so on. Any way, it won't do any harm to speak to him. I won't bother anybody to go with me. Stay here and make yourselves comfortable; I will dress and shove off."

When Dave had dressed and returned, he found every boy in the boat. Dick Pray was the first that had entered.

"Hullo!" shouted Dave. "All here, are you? That's good. The more the merrier."

"Dave, we loved you so much we couldn't leave you," asserted Dick.

"We will have a good time," said Dave. "All ready! Shove off! Bound for the lighthouse!"

The old schooner was left to its own reflections in the sober moonlight, and the boat slowly crept over the quiet waters to the tall lighthouse tower.

III.

DID THE SCHOONER COME BACK?

Mr. Toby Tolman sat in the snug little kitchen of the lighthouse tower. He was alone, but the clock ticked on the wall, and the kettle purred contentedly on the stove. Music and company in those sounds.

The light-keeper had just visited the lantern, had seen that the lamp was burning satisfactorily, had looked out on the wide sea to detect, if possible, any sign of fog, had "felt of the wind," as he termed it, but did not discover any hint of rough weather. Having pronounced all things satisfactory, he had come down to the kitchen to read awhile in his Bible. The gray-haired keeper loved his Bible. It was a companion to him when lonely, a pillow of rest when his soul was weary with cares, a lamp of guidance when he was uncertain about the way for his feet, a high, strong rock of refuge when sorrows hunted his soul.

"I just love my Bible," he said.

He had reason to say it. What book can match it?

As he sat contentedly reading its beautiful promises, he caught the sound of singing.

"Some fishermen going home," he said, and read on. After a while he heard the sound of a vigorous pounding on the lighthouse door.

"Why, why!" he exclaimed in amazement, "what is that?"

He rose and hastily descended the stair-way leading to the entrance of the lighthouse. To gain admission to the lighthouse, one first passed through the fog-signal tower. The lighthouse proper was built of stone; the other tower was of iron. They rose side by side. A covered passage-way five feet long connected the two towers, and entrance from the outside was first through the fog-signal tower. The foundation of each tower was a stubborn ledge that the sea would cover at high-water, and it was now necessary to have all doors beyond the reach of the roughly-grasping breakers. Otherwise they would have unpleasantly pressed for admittance, and might have gained it. The entrance to the fog-signal tower was about twenty feet above the summit of the ledge, and from the door dropped a ladder closely fastened to the tower's red wall. Around the door was a railed platform of iron, and through a hole in the platform a person stepped down upon the rounds of the ladder. Toby Tolman seized a lantern, and crossing the passage-way connecting the two towers, entered the fog-signal tower, and so gained the entrance. Just above the threshold of the door he saw the head and shoulders of a boy standing on the ladder.

"Why! who's this, at this time of night?" said Toby.

"Good-evening, sir. Excuse me, but I wanted to ask you something."

It was Dave Fletcher.

"Any trouble?"

"Well, yes."

"Come in, come in! Don't be bashful. Lighthouses are for folks in trouble."

"Thank you."

When Dave had climbed into the tower Dick Fray's curly head appeared.

"Oh, any more of you?" asked the keeper. "Bring him along."

"Good-evening," said Dick.

Then Jimmy Davis thrust up his head.

"Oh, another?" asked Toby. "How many?"

"Not through yet, Mr. Tolman," said Dave, laughing.

Johnny Richards stuck up his grinning face above the threshold.

"Any more?" said the light-keeper.

And this inquiry Dab Richards answered in person, relieving the ladder of its last load.

"Why, why! wasn't expecting this! All castaways?"

"Pretty near it, Mr. Tolman," said Dick.

"Come up into the kitchen, and then let us have your story, boys."

They followed the light-keeper into the kitchen, so warm, so cheerfully lighted.

In the boat Dick Pray had been very bold, and said he would go ahead and "beard the lion in his den;" but when at the foot of the lighthouse, he concluded he would silently allow Dave to precede him. The warmth of the kitchen thawed out Dick's tongue, and now that he was inside he kept a part of his word, and made an explanation to the light-keeper. He stated that they had had permission to "picnic" on the schooner, had--had--"got adrift"--somehow--and were caught on the bar, and the question was what to do.

"Perhaps you can advise us still further," explained Dave. "One suggestion is that when the tide turns we pull up anchor and drift back with the tide."

"Anchor?" asked Mr. Toby Tolman. "I thought you went on because you couldn't help it. Didn't know you dropped anchor there."

Dick blushed and cleared his throat.

"The schooner was anchored, but," said Dick, choking a little, "we--we--got--got--into water too deep for our anchor, and kept on drifting till the anchor caught in the bar."

"Oh!" said the light-keeper, who now saw a little deeper into the mystery, though all was not clear to him yet. "What will you do now? It is a good rule generally, when you don't know which way to move, not to move. Now, if you pull up anchor and let the next tide take you back, there is no telling where it will take you. Some bad rocks in our harbour as well as a lot of sand. 'Sharks' Fins' you know about. An ugly place. Now let me think a moment."

The light-keeper in deep thought walked up and down the floor, while the five boys clustered about the stove like bees flocking to a flaming hollyhock.

"See here: I advise this. Don't trouble that anchor to-night. The sea is quiet. No harm will be done the schooner, and her anchor has probably got a good grip on some rocks down below, and the tide won't start her. A tug will bring down a new schooner from Shipton to-morrow, and I will signal to the cap'n, and you can get him to tow you back. What say?" asked the keeper. "'Twill cost something."

"That plan looks sensible," said Dave. "I will give my share of the expense."

Dick looked down in silence. He wanted to get back without any exposure of his fault. The tug meant exposure, for the world outside would know it. The tide as motive power, drifting the schooner back, would tell no tales if the schooner went to the right place. There would, however, be danger of collision with rocks, and then the bill of expense would be greater and the exposure more mortifying. He scratched his head and hesitated, but finally assented to the tug-boat plan, and so did the other boys.

"Very well, then," said the keeper, "make yourselves at home, and I'll do all I can to make you comfortable."

What, stay there? Did he mean it? He meant a night of comfort in the lighthouse.

What a night that was!

"I wouldn't have missed it for twenty pounds," Johnny Richards said to those at home.

And the breakfast! It was without parallel. The schooner was held by its anchor inside the bar, and the boys in the morning visited their provision-baskets, and brought off such a heap of delicacies that the light-keeper declared it to be the "most satisfyin' meal" he had ever had inside those stone walls.

About nine o'clock he said, "Now, boys, I expect the tug-boat will be down with that schooner. When the cap'n of the tug-boat has carried her through the channel, I will signal to him--he and I have an understanding about it--and he will come round and tow you up, I don't doubt. You might be a-watching for her smoke."

Soon Dab Richards, looking up the harbour, cried out, "Smoke! she's coming!"

Yes, there was the tug-boat, throwing up a column of black smoke from her chimney, and behind her were the freshly-painted hull, and new, clean rigging of the lately launched schooner. The boys, save Dave, went to the Relentless, as the light-keeper said he would fix everything with the tug-boat, "make a bargain, and so on," and Dave could hear the terms and accept them for the party if he wished. The light-keeper had also promised in his own boat to put Dave aboard the tug.

But what other tug-boat was it the boys on the Relentless saw steaming down the harbour? They stood in the bow and watched her approach.

"She looks as if she were going to run into us," declared Dick.

"She certainly is pointing this way," thought Johnny.

"Our friends may be alarmed for us," was Dab's suggestion.

This could not be, the other boys thought, and they dismissed it as a teasing remark by Dab. And yet the tug-boat was coming toward them like an arrow feathered with black smoke and shot out by a strong arm.

"It is certainly coming toward us," cried Dick in alarm. Who was it his black eyes detected among the people leaning over the rail of the nearing tug-boat?

He looked again.

He took a third look.

"Boys," he shouted, "put!"

How rapidly he rushed for a hatchway, descending an old ladder still in place and leading into the schooner's hold! Fear is catching. Had Dick seen a policeman sent out in a special tug to hunt up the boys and secure the vessel? Johnny Richards flew after Dick. Jimmy Davis followed Johnny. Dab was quickly at the heels of Jimmy. Down into the dark, smelling hold, stumbling over the keelson, splashing into the bilge water, and frightening the rats, hurried the still more frightened boys.

"Who was it, Dick?" asked Dab.

"Keep still boys; don't say anything."

"Can't you tell his name?" whispered Johnny.

There it was, down in the dark, that Dick whispered the fearful name. When the tug-boat, the Leopard, carrying Dave neared the schooner, the captain said, "You have another tug there. It is the Panther."

The Leopard hated the Panther, and would gladly have clawed it out of shape and sunk it.

"I don't understand why the Panther is there," said Dave; "I really don't know what it means."

"You see," said the master of the Leopard fiercely, "if that other boat is a-goin' to do the job, let her do it (he will probably cheat you). I can't fool away my time. The Sally Jane is waitin' up stream to be towed down, and I would like to get the job."

"We will soon find out what it means, sir. Just put me alongside the schooner."

"I will put my boat there, and you can jump out."

Who was it that Dave saw on the schooner's deck? Dave trembled at the prospect. He could imagine what was coming, and it came.

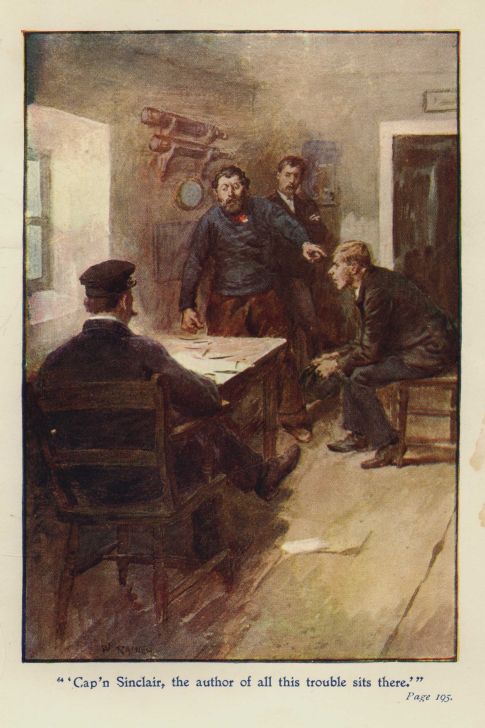

"Here, young man, what have you been up to? A precious set of young rascals to be running off with my property. I thought you said you would be particular. The state prison is none too good for you," said this unexpected and gruff personage.

"Squire Sylvester," replied Dave with dignity, "just wait before you condemn after that fashion; wait till you get the facts. I did try to be particular. I don't think it was intended when it was done; boys don't think, you know--"

"When what was done?"

"Why, the anchor lifted--weighed--"

"Anchor lifted!" growled Squire Sylvester. "What for?"

"Just to see it move, and have a little ride, I think."

"Have a little sail! Didn't you know, sir, it was exposing property to have a little sail?"

Here the squire silently levelled a stout red forefinger at this opprobrious wretch, this villain, this thief, this robber on the high seas, this--with what else did that finger mean to label David Fletcher?

"But the anchor was dropped again, and it was thought, sir, that it--that it would stop--"

"And the vessel did not stop! Might have guessed that, I should say. You got into deep water."

"We were going to hire the Leopard to tow it back, and any damages would have been paid. I am very sorry--"

"No apologies, young man. What's done is done. I have got a tug-boat to take the vessel back."

"And you don't want me?" here shouted the captain of the Leopard.

"Of course not," muttered the captain of the Panther, showing some white teeth in derision.

"I don't know anything about you," said Squire Sylvester to the captain of the Leopard; "this other party may settle with you."

"I'll pay any bill," said Dave to the Leopard, whose steam was escaping in a low growl.

"Can't waste any more time," snarled the Leopard. He rang the signal-bell to the engineer, and off went his tug.

"Well, where are your companions?" said Squire Sylvester to Dave.--"O Giles," he added to the Panther, "you may start up your boat if you have made fast to the schooner."

"Weigh the anchor fust, sir."

"Oh yes, Giles."

The anchor weighed, the Panther then sneezed, splashed, frothed, and the Relentless followed it. Squire Sylvester declared that he must find the other runaways; that they must be on board the schooner, and he would hunt for them. He discovered them down in the hold, and out of the shadows crawled four sheepish, mortified hide-aways.

And so back to its moorings went the old schooner.

Back to his office went Squire Sylvester, mad with others, and mad with himself because mad with others.

Back to their homes went a shabby picnic party, and after them came a bill for the expense of the Relentless's return trip. It costs something in this life to find out that the thing easily started may not be the thing easily stopped.

IV.

WHAT WAS HE HERE FOR?

Bartie Trafton, alias Little Mew, was crouching behind a clump of hollyhocks in a little garden fronting the Trafton home. It was a favourite place of retreat when things went poorly with Little Mew. They had certainly gone unsatisfactorily one day not long after the sail that was not a sail. He had perpetrated a blunder that had brought out from Gran'sir Trafton the encouraging remark that he did not see what the boy was in this world for. Bartie had retreated to the hollyhock clump to think the situation over. He was ten years old, and life did have a hard look to Little Mew. He never supposed that his father cared much for him. When the father was ashore he was drunk; when he came to his senses, and was sober, then he went to sea. Bart sometimes wondered if his mother thought of him and knew how he was situated.

"She's up in heaven," thought Bart among the hollyhocks, and to Bart heaven was somewhere among the soft, white clouds, floating like the wings of big gulls far above the tops of the elms that overhung the roof of the house and looked down upon this poor little unfortunate. If earth brought so little happiness, because bringing so little usefulness, then why was Bart on the earth at all?

"I don't see," he murmured.

The question was a puzzle to him. He was still looking up when he heard the voice of somebody calling.

"It is somebody at the fence," he said. It was a musical voice, and Bart wondered if his mother wouldn't call that way. He turned; and what a sweet face he saw at the fence!--a young lady with sparkling eyes of hazel, fair complexion, and cheeks that prettily dimpled when she laughed. He surely thought it must be his mother grown young and come back to earth again. There was some difference between that face, so picturesquely bordered with its summer hat, and the puzzled, irregular features under the old, ragged straw hat that Bart wore.

"Are you the little fellow I heard about that got into the water one day?" asked the young lady.

"Yes'm," said Bart, pleased to be noticed because he had been in the water, while thankful to be out of it.

"Well, I'm getting up a Sunday-school class, and I should like very much to have you in it. Would you like to come?"

"Yes'm," said Bart eagerly, "if--if granny and gran'sir would let me."

"Where are they? You let me ask them."

"She's got a lot of tunes in her voice," thought Bart, eagerly leading the young lady into the presence of granny and gran'sir.

They were in a flutter at the advent of so much beauty and grace, and gave a ready permission.

"Now, Bartie--that is your name, I believe--"

"Yes'm."

"I shall expect you next Sunday down at that brick church, Grace Church, just on the corner of Front Street."

"I know where it is."

"And one thing more. Do you suppose you could get anybody else to come?" asked the young lady.

"I'll try."

"That's right. Do so. Good-bye."

"Good-bye."

Bart was puzzled to know whom to solicit for the Sunday school. Gran'sir was so much interested in the young lady that Bart concluded gran'sir would be willing to go if asked and if well enough; but Bart concluded that gran'sir was too old, and he said nothing. Sunday itself, on his way to the church, Bart saw a recruit. It was Dave Fletcher.

"Oh, you will go with me, won't you? I haven't anybody yet," he said eagerly.

"What do you mean?" replied the wondering Dave.

"Oh, go to Sunday school with me. I said I would try to bring some one."

Dave smiled, and Bart interpreted the smile as one half of an assent.

"Oh, do go! I said I would try. And she's real pretty."

"Who? your teacher?"

"Yes."

"Well, that is an inducement. But I am only going to be here a Sunday or two. My visit is almost over."

"Oh, well, it would please teacher."

Dave smiled again, and this Bart interpreted as the other half of the assent desired.

"Oh, I am so glad! I'll tell you where it is."

"W-e-l-l! It won't do any harm. I can go as visitor, and I suppose it would please my family--"

"Family?"

"My father and mother and sister, if they should know I had visited the Sunday school. Come along! We don't want to be late, you know. I'll be visitor, and perhaps they will want me to make a speech at the school. Ha! ha!"

Bart pulled Dave eagerly into the entry of the church, and then looked through the open door into the room where he knew the Sunday school met; for Bart had been a visitor once in that very same place.

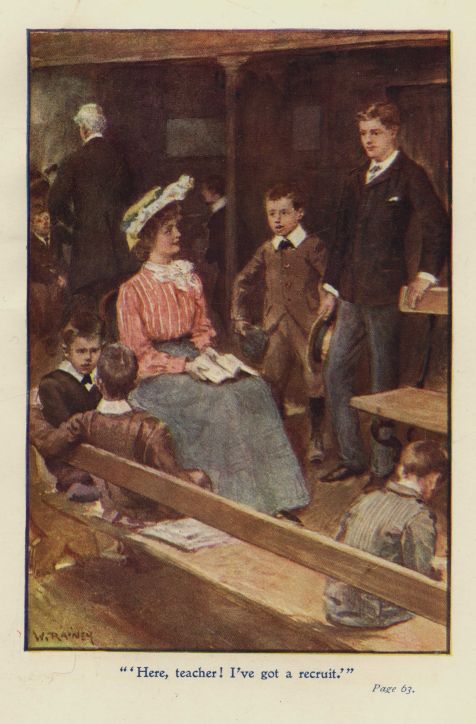

"Oh, I see teacher," thought Bart, spying his friend in a seat not far from the door. Her back was turned toward him, but he had not forgotten the pretty summer hat with its fluttering ribbons of blue. Dave, with a smile, followed the little fellow, who was timorously conveying his prize to the waiting young lady. She looked up as Bart exclaimed, "Here, teacher! I've got one."

"Why, Dave," she exclaimed, "where did you come from?"

"Annie--this you?" he said. The two began to laugh. Bart in surprise looked at them.

"This is my sister, Bart," explained Dave. "Ha! ha!"

That beautiful young lady and the big boy who had saved him sister and brother? He might have guessed such a friend as Dave would have such a sister as this nice young lady. She was visiting at Uncle Ferguson's.

"You see, Dave, when I began my visit I did not expect to teach while here; but I met the minister, Mr. Porter, and he said he wished I would start another class for him in his Sunday school and teach it while here, and I could not say no; and went to work, and have been picking up my class. I didn't happen to tell you."

The Rev. Charles Porter, at this time the clergyman at Grace Church, was an old friend of the Fletcher family. Meeting Annie in the streets of Shipton, and knowing what valuable material there was in the young lady, he desired to set her to work at once; and when her stay in town might be over, he could, as he said, "find a teacher, somebody to continue to open the furrow that she had started."

Dave enjoyed the situation.

"I will play that I am superintendent, Annie, and have come to inspect your class, and will sit here while you teach."

"I don't know about allowing you to stay here, sir, unless you become a member of the class and answer my questions, Dave."

Annie was relieved of the presence of this inspector; for a gentleman at the head of a class opposite, noticing a big boy among Annie's flock of little fellows, kindly invited Dave to sit with his older lads.

"I am Mr. Tolman," said the gentleman. "Make yourself at home among the boys."

"Thank you, sir," said Dave; and his sister, with a roguish smile, bowed him out of her class.

That Sunday was an eventful day to Little Mew. It was pleasant any way to be near this young lady, who seemed to him to be some beautiful being from a sphere above the human kind in which he moved. And then Bart was interested in the subject Annie presented. She talked about heaven and its people. She talked about God; but she did not make him that far-off being that Bart thought he must be, so that the louder people prayed the quicker they would bring him. She told how near he was, all about us, so that we could seem to hear his voice in the pleasant wind, and feel his touch in the soft, warm sunshine.

"But--but," said Bart, "he seems to be behind a curtain. I don't see him."

And then the teacher, her voice to Bart's ear playing a sweeter tune than ever, told how God took away the curtain; how he came in the Lord Jesus Christ; that the Saviour was the divine expression of God's love; and men could see that love going about their streets, coming into their homes, healing their sick, and then hanging on the cross that the world might be brought to God. Bart had been told all this before, but somehow it never got so near him.

"What she says somehow gets into me," thought Bart, looking up into the teacher's face. He thought he would like to ask her one question when he was alone with her. The school was dismissed, and Bart lingered that he might walk away with the teacher.

"Could I ask you about something?" he said, trotting at her side and lifting his queer, oldish face towards her.

"Certainly; ask all the questions you want. I can't say that I can answer them, but there's no harm in asking them."

"Well, what am I in this world for?"

He said it so abruptly that it amused Annie.

"What are you in this world for?"

"Yes'm. I don't seem to amount to much."

Bart eagerly watched the face above him, that had suddenly grown serious; for Annie was thinking of the little fellow's home--of its unattractiveness, of the two old people there that seemed so uninteresting, especially the grandfather, who, as Annie recalled him, seemed to be only a compound of a whining voice, a gloomy face, a bad cough, and a clumsy cane. Then she recalled the slighting way in which she heard people speak of this odd little fellow, who seemed to be a figure out of place in life's problem; one who seemed to run into life's misfortunes, not waiting that they might run into him--one ill-adjusted and awry. Well, what should she say? She thought in silence. Then she stopped him, and looked down into his face.

Bart never forgot it. It was as if all of heaven's beautiful angels she had told about that day were looking at him through her face, and all of heaven's beautiful voices were speaking in her tones.

"Bart," she said, "the great reason why you are in this world is because--God loves you."

What? He wanted to think that over.

"Because what?" he said.

"Why, Bart," she said, "God is a Father--a great, dear Father."

Bart began to think he was; but he had been getting his idea of God through gran'sir's style of religion, and God seemed more like a judge or a big police-officer--catching up people and always marching them off to punishment.

"God is a great, dear Father," the tuneful voice was saying, "and he wants somebody to love him; and the more people he makes, the more there are to love him, or should be, and so he made you. But oh, if we don't love him, it disappoints and grieves him!"

"Does it?" said Bart, thoughtfully, soberly.

"When you are at home--alone, upstairs--you tell God how you feel about it, just as you would tell your mother--"

"Or teacher," thought Bart.

"As you would tell your mother if she were on the earth."

That day, all alone hi his diminutive chamber, kneeling by a little bed whose clothing was all too scanty in cold weather, a boy told God he wanted to love him. When Bart rose from his knees he said to himself, "Now, I must try to love other people."

He went downstairs. Gran'sir was lying on a hard old lounge, making believe that he was trying to read his Bible, and at the same time he was very sleepy. Bart hesitated, and then said,--

"Gran'sir, don't you--you--want me to get you a pillow and put under your head?"

"Oh, that's a nice little boy!" said the weary old grandfather, when his head dropped on the soft pillow now covering the hard arm of the lounge.

"And, gran'sir, I ain't much on readin'; but perhaps, if you'd let me, I might read something, you know."

"Oh, that's a dear little feller," said gran'sir, closing his eyes, so old and tired. He had been trying to read about Jacob and the angels at Beth-el; but the lounge was so tough that the feature of the story gran'sir seemed to appreciate most sensibly was that Jacob slept on a pillow of stones. I can't say how much of the story, as Bart read it, gran'sir heard that day, for he was soon as much lost to the outside world as tired Jacob was. He had, though, a beautiful dream, he afterwards told granny. Yes; in his sleep he seemed to see the ladder with its shining, silver rounds, climbing the sky, and on them were so many angels, oh, so many angels!

"And, granny," whispered gran'sir, "I was a little startled, for one of them angels seemed to have Bartie's face. I hope nothin' is goin' to happen, for I am beginnin' to think we should miss that little chap ever so much."

V.

THE LIGHTHOUSE.

"You say this is your last Sunday at Shipton. Sorry! We shall miss you in the class," said Dave's new Sunday-school acquaintance, Mr. Tolman.

"Thank you, sir," replied Dave; "but as this is only my second Sunday in your class, you won't miss me much."

"Oh yes, we shall. See here, David. There is going to be some company at my house to-morrow night. Bring your sister round to tea."

Dave and Annie were at Mr. Tolman's the evening of the next day; and who was it Dave saw trying to shrink into one corner? A stout, fat man, altogether too big for the corner.

"He looks natural," thought Dave.

At this point the man saw Dave. He had been looking very lonely, but his face now brightened as if he had suddenly seen an old and valued acquaintance.

"Think you don't remember me!" he said, advancing toward Dave, and extending a large brown hand shaped something like a flounder. Dave thought at once of a lighthouse, a sand-bar, and an old schooner halting on the bar.

"Oh, the light-keeper, Mr. Tolman!" cried Dave. "You here?"

"It is my uncle from Black Rocks," said the younger Mr. Tolman, stepping up to this party of two. "Uncle Toby doesn't get off very often from the light, and we thought he ought to have a little vacation, and come and see his relatives."

"My nephew James is very good," said Mr. Toby Tolman. "The last time I saw you," he added, addressing Dave, "I put you on board that tug-boat."

Dave dropped his head.

"Oh, you needn't be ashamed of that affair. I didn't think at the time you could be the cause of the mischief, and I've been told since who it was that was to blame for it."

Dave raised his head.

"Fact is I've been a-thinking of you. Want a job, young man?"

"Me, sir? I expect to go home to-morrow."

"Got to return for anything special?"

"Well, my visit is out."

"Nothing special to call you home?"

"Oh, I help father, and go to school when there is one."

"Well," said the old light-keeper, fixing his eyes on the boy, "how should you like to help to keep a lighthouse for three weeks?"

"Me?" said Dave eagerly.

"Yes, you. You know I have an assistant, Timothy Waters. He wants to be off on a vacation for three weeks, and I must have somebody to take his place. I want somebody who can work in there, sort of spry and handy. Now, I think you would do. How should you like it?"

"When do you want to know?"

"The last of this week."

"I will go home to-morrow and talk it over with the folks, and I can get you an answer by day after to-morrow."

"Yes, that will do."