|

THRILLING ADVENTURE |

MOTOR FICTION |

|

NO. 28 SEPT. 4, 1909. |

FIVE CENTS |

|

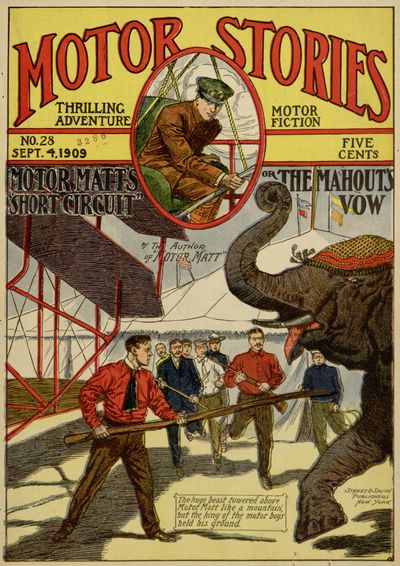

MOTOR MATT'S "SHORT CIRCUIT" |

or THE MAHOUT'S VOW |

| by The Author of "Motor Matt" | |

|

Street & Smith Publishers New York |

|

| MOTOR STORIES | |

| THRILLING ADVENTURE | MOTOR FICTION |

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Copyright, 1909, by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

| No. 28. | NEW YORK, September 4, 1909. | Price Five Cents. |

Motor Matt's "Short=circuit"

OR,

THE MAHOUT'S VOW.

By the author of "MOTOR MATT."

CHAPTER I. THE SERPENT CHARMER.

CHAPTER II. A BAD ELEPHANT.

CHAPTER III. BURTON'S LUCK.

CHAPTER IV. MOTOR MATT'S COURAGE.

CHAPTER V. DHONDARAM'S EXCUSE.

CHAPTER VI. ROBBERY.

CHAPTER VII. BETWEEN THE WAGONS.

CHAPTER VIII. A PEG TO HANG SUSPICIONS ON.

CHAPTER IX. A WAITING GAME.

CHAPTER X. A TRICK AT THE START.

CHAPTER XI. IN THE AIR WITH A COBRA.

CHAPTER XII. A SCIENTIFIC FACT.

CHAPTER XIII. PING ON THE WRONG TRACK.

CHAPTER XIV. FACING A TRAITOR.

CHAPTER XV. MEETING THE HINDOO.

CHAPTER XVI. A BIT OF A BACKSET.

ON THE BAHAMA REEFS.

THE STORY OF A WILD GOOSE.

Matt King, otherwise Motor Matt.

Joe McGlory, a young cowboy who proves himself a lad of worth and character, and whose eccentricities are all on the humorous side. A good chum to tie to—a point Motor Matt is quick to perceive.

Ping, a Chinese boy who insists on working for Motor Matt, and who contrives to make himself valuable, perhaps invaluable.

Carl Pretzel, an old chum who flags Motor Matt and more trouble than he can manage, at about the same time. In the rôle of detective, he makes many blunders, wise and otherwise, finding success only to wonder how he did it.

Dhondaram, a Hindoo snake charmer and elephant trainer, who is under an obligation to Ben Ali and gets into trouble while trying to discharge it.

Andy Carter, ticket-man for Burton's Big Consolidated Shows; a traitor to his employer, and who emerges from his evil plots with less punishment than he deserves.

Boss Burton, manager and proprietor of the "Big Consolidated," who, in his usual manner, forms hasty conclusions, discovers his errors, and shows no sign of repentance.

Archie Le Bon, a trapeze performer who swings on a flying bar under Motor Matt's aëroplane—and has a bad attack of nerves.

Ben Ali, an old Hindoo acquaintance who figures but briefly in the story. His vow, and the manner in which he sought its fulfillment, brings danger to the king of the motor boys.

THE SERPENT CHARMER.

A brown man in a white turban sat by the river. It was night, and a little fire of sticks sent strange gleams sparkling across the water, and touched the form of the brown man with splashes of golden light.

The man was playing on a gourd flute. The music—if such it could be called—was in a high key, but stifled and subdued. Under the man, to keep his crouching body from the earth, had been spread a piece of scarlet cloth. In front of him was a round wicker basket, perhaps a foot in diameter by six inches high.

As the man played, the notes of the flute coming faster and faster, the lid of the basket began to tremble as by some pent-up force. Finally the lid slid open, and a hooded cobra lifted its flat, ugly head. With eyes on those of the serpent charmer, the cobra began weaving back and forth in time to the music. Now and then the snake would hiss and dart its head at the man. The latter would dodge to avoid the striking fangs, meanwhile keeping up his flute-playing.

It was an odd scene, truly, to be going forward in a country like ours—cut bodily from the mysteries of India and dropped down on the banks of the Wabash, there, near the intensely American city of Lafayette.

While the brown man was playing and the cobra swayed, and danced, and struck its lightning-like but ineffectual blows, another came into the ring of firelight, stepping as noiselessly as a slinking panther. He, like the other, wore a turban, and there was gold in his ears and necklaces about his throat.

The first man continued his flute-playing. The other, with a soft laugh, went to the player's side, sank down, and riveted his own snakelike orbs upon the diamond eyes of the cobra. Once the serpent struck at him, but he drew back and continued to look. With one hand the newcomer took the flute from the player's lips and laid it on the ground; then, in a silence broken only by the crackling fires, the eyes of the man snapped and gleamed and held those of the cobra.

The effect was marvelous. Slowly the cobra ceased its rhythmical movements and dropped down and down until[Pg 2] it retreated once more into the basket; then, with a quick hand, the lid of the receptacle was replaced and secured with a wooden pin.

"Yadaba!" exclaimed the first man.

"Not here must you call me that, Dhondaram," said the second. "I am known as Ben Ali."

Dhondaram spat contemptuously.

"'Tis a name of the Turks," he grunted; "a dog's name."

"It answers as well as any other."

These men were Hindoos, and their talk was in Hindustani.

"You sent for me at Chicago," proceeded Dhondaram; "you asked me to come to this place on the river, and to bring with me my most venomous cobra. See! I am here; and the cobra, you have discovered that the flute has no power to quiet its hostility. Your eyes did that, Yada—your pardon; I should have said Ben Ali. Great is the power of your eyes. They have lost none of their charms since last we met."

Ben Ali received this statement moodily. Picking up a small pebble, he cast it angrily into the fire.

"Why have you brought me here?" inquired Dhondaram, rolling a cigarette with materials taken from the breast of his flowing robe.

"Because," answered Ben Ali, "I have made a vow."

"By Krishna," and Dhondaram threw himself forward to light his cigarette at the fire, "vows are evil things. They bring trouble—nothing less."

"This one," hissed Ben Ali, "will bring trouble to an enemy of mine."

"And to yourself, it may be," added Dhondaram, resuming his squatting attitude on the scarlet cloth and whiffing a thin line of vapor into the air.

"The goddess Kali protects me," averred Ben Ali. "It is written in my forehead."

"What else is written in your forehead?" asked Dhondaram after a space. "What was it that caused you to send for me, and to ask me to leave my profitable work in the museum, come here, and bring the worst of my hooded pets?"

Ben Ali, in the silence that followed, picked up more pebbles and cast them into the fire.

"During the feast of Nag-Panchmi," he observed at last, "years since, Dhondaram, a mad elephant crushed a boat on the Ganges. You were in the boat, and I snatched you from certain death."

Dhondaram's face underwent a swift change.

"That, also," he said in a subdued tone, "is written in my forehead. I remembered it when your letter came to me. I owe you obedience until the debt is paid. I am here, Ben Ali. Command me."

"Such baht! You, with the cobra, Dhondaram, will go against my enemy and fulfill my vow. That will repay the debt."

A look of fear crossed Dhondaram's face. It passed quickly, but had not escaped the keen eyes of Ben Ali.

"You are afraid!" and he sneered as he spoke.

"And if I am?" protested the other. "I am bound to obey, and lose my life, if I must, in paying for the saving of it during the feast of Nag-Panchmi. Who is your enemy, Aurung Zeeb?"

Ben Ali struck the ground with his clinched fist.

"Aurung Zeeb is a coward!" he exclaimed. "He fled and left me to work out my vengeance alone. Hurkutjee! Let us speak no more of him. You knew of my brother, the rajah? How our sister married the feringhi, Captain Lionel Manners, of the English army? How he died, and his wife perished in the ghats, by suttee? Of the daughter they left, Margaret Manners? How, out of hatred to the rajah, I brought the girl to this country and destroyed her will by the power of the eyes? How we traveled with the show of Burton Sahib?"

Dhondaram nodded gravely.

"I know," he replied.

"But you do not know of the feringhi boy, the one who flies in the bird machine, and who is called Motor Matt. Because of him I have lost the girl, and she was making much money for me. I was mahout in the show for Burton Sahib's worst elephant, Rajah. No other could drive him, or take care of him. You are a sapwallah, a charmer of serpents, but you are also a charmer of elephants. You can drive them, Dhondaram, as well as I. You can take care of this Rajah beast as well as I."

"I learned to work with the elephants from my brother, the muni," observed Dhondaram. "You have lost the niece you called Haidee?"

"She is under the care of the British ambassador, but she is staying in this town. Perhaps I may get her back—that I do not know. But my vow, Dhondaram, against this feringhi boy, Motor Matt. That is for you to carry out. He has wrecked my plans. I will wreck his. He has put me in danger of my life. Through me, he shall be in danger of his own."

"What am I to do?" queried Dhondaram.

"The show of Burton Sahib is some distance from here, but I will tell you how to find it. The cobra will help you join it, for Burton Sahib is always watching for performers. You must learn to do better with this cobra. By performing with the serpent before Burton Sahib, you will please him. He must have some one to take care of the elephant, Rajah. You will apply for the place. Ha! Do you follow me?"

Dhondaram nodded.

"When you have applied for the place I will tell you what to do. The air machine must be wrecked. Rajah will do that. The feringhi boy must be put where he will not interfere with my plans for my niece—the cobra must do that."

Dhondaram stirred restlessly.

"The law of this country," he murmured, "has a long arm and a heavy fist."

"If you do as I say," went on Ben Ali, "you will not be reached by the arm nor caught by the fist. You will be safe, and so will I; and the vow of Ben Ali will have been carried out."

"You cannot do this yourself?"

"I should be seized if I showed my face again in the show of Burra Burton! I should be thrown into the strong house of the feringhis if I appeared among the tents. Motor Matt has said this, and he has the power to carry out his threat."

"Had Motor Matt the power to do this when he saved Haidee?"

"He had."

"And he held his hand! Why?"

"Because Haidee was under the spell of my eyes. In order to free her, he had to bargain with me. The bargain was that I should go free, but never to trouble Motor Matt or the girl any more. With the girl in my hands, I could secure many rupees from my brother, the rajah, for her. And I hate that brother. He is rich, but[Pg 3] he made me the keeper of his elephants! He lived in luxury, but I herded with the coolies."

Again Ben Ali struck his clinched fist on the earth.

"It may be," said Dhondaram, "that Burton Sahib has secured another keeper for the bad elephant, Rajah? In that case, he would not want me."

"It is not likely," returned Ben Ali. "All the other keepers are afraid of Rajah. Aurung Zeeb was the only Hindoo who could have managed Rajah, and he dare not return to the show any more than I. Burton Sahib will want some one, and he will take you. You will go to him, perform with the cobra, win his favor. Then, and not till then, you will ask for the post of elephant keeper. Burton Sahib, my word for it, will give you Rajah to look after. Then, my friend, you can carry out the terms of my vow. You will pay your debt, and we shall be quits. I shall have no further claim on you."

"And I shall escape the arm of the feringhi law?"

"Even so."

"Tell me what I am to do, and how."

Then, as the little tongues of flame threw their weird play of lights and shadows over the dusky plotters, the talk went on.

A BAD ELEPHANT.

"Great spark-plugs!"

Motor Matt was passing the canvas walls of the menagerie tent of the "Big Consolidated" when a human form ricocheted over the top of it and landed directly in front of him on a pile of hay. The dropping of the man on the hay was accompanied by a wild sound which the king of the motor boys recognized as the trumpeting of an angry elephant. Following this came the noise of quick movements on the other side of the wall, and hoarse voices giving sharp commands.

Matt ran to the man who had fallen on the hay. He was sitting up and staring about him blankly.

"Well, if it isn't Archie Le Bon!" exclaimed Matt. "What sort of way is that to come out of a tent, Le Bon?"

"Couldn't help myself, Matt," was the answer. "A couple of tons of mad elephant gave me a starter. Gee! No more of that in mine. I'm glad this hay happened to be here."

Le Bon got up. Evidently his brain was dizzy, for he supported himself against a guy rope.

"Was it Rajah?" asked Matt.

"Yes."

"Don't you know any better than to fool with that big lump of iniquity?"

"I do now. Burton has offered twenty-five dollars to any one connected with the show who'll take Rajah out in the parade. Thought I'd try it, and I began by doing my best to make friends with the brute. Rajah was about two seconds wrapping his trunk around me and heaving me over the wall. I'm in luck at that, I suppose. The big fellow might have slammed me on the ground and danced a hornpipe on me."

"You don't mean to say that Burton is going to have Rajah in the parade!" exclaimed Matt.

"Says he is," answered Le Bon, "but I'll bet money he won't get any one to ride the elephant. You'd better trot along inside. Your Dutch pard, Carl, had a row with me. We both wanted to try and manage Rajah and annex the twenty-five, and the only way we could settle the question was by drawing straws. For all I know, Carl may be trying to make friends with Rajah now. Head him off, Matt, or there'll be a dead Dutchman on the grounds."

"Carl must be crazy!" exclaimed Matt, whirling around and darting under the canvas.

Archie Le Bon was an acrobat, and one of several brothers who had a hair-raising act in the circus ring; and if Archie couldn't manage Rajah, it was a foregone conclusion that Carl wouldn't be able to.

Still, it was like Carl to be willing to try something of the sort, and the young motorist was eager to call a halt in proceedings before it was too late.

Inside the "animal top" a crowd of men was belaboring Rajah with clubs and sharp prods. The elephant, chained to stakes firmly planted in the ground, was backing away as far as the chains would permit, head up and trunk in the air. Boss Burton, proprietor and manager of the show, was directing operations.

Matt's Dutch pard was very much in evidence. Armed with a piece of sharpened iron, he was hopping around like a pea on a hot griddle, taking a hack at Rajah every time he saw an opening. Joe McGlory was hopping around, too, trying to grab the excited Dutchman and snake him out of harm's way.

Suddenly Rajah lowered his head and executed a wide sweep with his trunk, in a half circle. Carl and a mahout who had charge of the other elephants had their feet knocked from under them. The mahout was thrown flat and quickly dragged to safety, while Carl was stood on his head in a bucket—a bucket that happened to be filled with water.

McGlory caught Carl by the heels and dragged him out into the centre of the tent, the Dutchman thrashing his arms and sputtering as he slid over the ground.

"Confound the brute!" roared Boss Burton; "I'll either take the kinks out of him and have him in the parade, or I'll shoot him. Leave him alone for half an hour, and then we'll maul him some more. How's Le Bon?"

"Not a scratch," Archie Le Bon answered for himself, coming in under the canvas. "But I might have had a broken head."

"You've had enough?" queried Burton.

"A great plenty, thank you. I'm no elephant trainer, Burton, and while I'd like to make a little extra money I guess I'll look for something that's more congenial."

"Dot's me, too," said Carl to Matt and McGlory. "I don'd vas some elephant trainers, I bed you. Vat a ugliness old Racha has! Dot trunk oof his hit me like a railroadt train."

"You were going to try and ride the elephant in the parade, Carl?" demanded Matt.

"I vas t'inking oof id vonce, aber never any more. He iss vorse as I t'ought."

"I heard what he was up to, Matt," put in McGlory, "and hit the high places for here. Arrived just in time to see Le Bon go out between the edge of the wall and the edge of the tent top. Sufferin' skyrockets, but it was quick! Everybody rushed at Rajah, and Carl was right in the thick of it. I thought he'd be smashed into a cocked hat before I could get hold of him."

"Who vas der feller vat left dot pucket oof vater in der vay?" grumbled Carl, mopping his tow hair with a red cotton handkerchief. "Id vas righdt under me ven I[Pg 4] come down. I don'd like dot. Id vas pad enough mitoudt any fancy drimmings in der vay oof a pail oof vater."

"Well, it's a lesson for you to leave Rajah alone."

"T'anks, I know dot. Oof he vas der only elephant vat dere iss, I vouldn't haf nodding to do mit him. Vile I'm vaiding for dot fordune to come from India I haf got to lif, but I vill shdarve pefore I dry to make a lifing taking care oof Racha. Br-r-r, you old sgoundrel!" and Carl turned and shook his fist at Rajah.

Just at this moment Boss Burton stepped up to Matt and his friends.

"Here's a hard-luck proposition!" he glowered. "My biggest elephant raises Cain in a way he never did while Ben Ali had charge of him. Ben Ali was a villain, but he knew how to manage elephants. But Rajah goes in the parade, you can bet your pile on that."

"You don't mean it, Burton!" cried Motor Matt.

"Oh, don't I?" and there was a resolute gleam in the showman's eyes as he faced Matt. "You watch and see," he added.

"You're taking a lot of chances if you stick to that notion," grunted McGlory. "The brute's liable to smash a few cages and let loose a lion or two. By the time you foot the bill, Burton, you'll find you're riding a mighty expensive hobby."

"Rajah goes in the parade," shouted the angry showman, "or I put a bullet into him. I've got my mad up now."

"Who'll take him?" queried Matt.

"If I can't find any one to put him through his paces, by gorry I'll do it myself!"

"Then the Big Consolidated," said McGlory, "might as well look for another boss."

"See here, Burton," went on Matt, "you've been having the aëroplane tag your string of four elephants during the parade, and Rajah's been at the end of the string and right in front of the flying machine. You've got to give the machine another place. I'll not take chances with it, if Rajah's in the march. You ought to remember what a close call the brute gave us in Lafayette."

"Nobody's going to change places in the parade!" declared Burton.

He was a man of mercurial temperament, and could only be managed by firmness.

"Either Rajah stays out of the procession," exclaimed Motor Matt calmly, "or the Comet does."

"And you can paste that in your hat, Burton," added McGlory. "What Pard Matt says goes."

"Oh, hang it," growled Burton, coming to his senses; "if you fellows bear down on me like that, of course you win out; but I hate to have a measly elephant butt into my plans and make me change 'em. Now——"

"Say, Mr. Burton," spoke up a canvasman, stepping to the showman's side and touching his arm, "there's a dark-skinned mutt in a turban what wants ter see ye in the calliope tent."

Burton whirled on the canvasman.

"Dark skinned man in a turban?" he repeated. "Does he look like a Hindoo?"

"Dead ringer for one."

"Maybe it's Ben Ali——"

"No, he ain't. I know Ben Ali, and this ain't him."

"That tin horn won't show up among these tents in a hurry, Burton," said McGlory. "He knows he'll get what's coming, if he does."

"Then," continued Burton, "it's dollars to dimes it's Aurung Zeeb."

"Not him, neither," averred the canvasman. "This bloke wears a red tablecloth and carries a basket. Looks ter me like he had somethin' he wanted ter sell."

"I'll go and talk with him. Come on, Matt, you and McGlory."

Matt, McGlory, and Carl followed the showman under the canvas and into the calliope "lean-to." Here there was a chocolate-colored individual answering the canvasman's description. But he was not wearing the red tablecloth. Instead, he had spread it on the ground and was sitting on it. In front of him was a round, flat-topped basket, and in his hands was a queer-looking musical instrument.

"You want to see me?" demanded the showman, as he and the boys came to a halt in front of the Hindoo.

The latter swept his eyes over the little group.

"You Burton Sahib?" he inquired, bringing his gaze to a rest on the showman.

"Yes," was the answer.

"You look, see what I can do?" queried the Hindoo.

"If you've got something you want to sell——"

"The honorable sahib makes the mistake. Dekke!"

Then, with this native word, which signifies "look," the Hindoo dropped his eyes to the round, flat basket and brought the end of the musical instrument to his lips.

BURTON'S LUCK.

While the notes of the gourd flute echoed through the tent, the cover of the round basket began to quiver and shake. Finally it slipped back, and there were startled exclamations and a brisk, recoiling movement on the part of the spectators as the head of a venomous cobra showed itself.

"A snake charmer!" muttered Burton, disappointment in his voice. "They're as common as Albinos—and about as much of a drawing card."

"That's a cobra di capello he's working with," remarked Matt, staring at the snake with a good deal of interest. "I saw one in a museum once, and heard a lecturer talk about it. The lecturer said that the bite of a cobra is almost always fatal, and that there is no known antidote for the poison; that the virus works so quickly it is even impossible to amputate the bitten limb before the victim dies."

"Shnakes iss pad meticine," muttered Carl, "und I don'd like dem a leedle pit."

"Sufferin' rattlers!" exclaimed McGlory. "I've been up against scorpions, Gila monsters, and tarantulas, but blamed if I ever saw a snake in a sunbonnet before—like that one."

The cobra's hood, which was fully extended, gave it the ridiculous appearance of wearing a bonnet, and there was something grewsome in the way the reptile's head swayed in unison with the flute notes. Suddenly the head darted sideways.

Motor Matt's quickness alone kept him from being bitten. He leaped backward, just in the nick of time to avoid the darting fangs. McGlory, wild with anger,[Pg 5] picked up an iron rod that was used about the calliope and made a threatening gesture toward the snake.

"Speak to me about that!" he breathed. "What kind of a snake tamer are you, anyhow? If you think we're going to stand around and let that flat-necked poison thrower get in its work on us, you——"

The cowboy made ready to use the rod, but Matt caught his arm.

"Hold up, Joe," said Matt. "No harm has been done, and this is a mighty interesting performance."

"Aber der sharmer don'd vas aple to put der shnake to shleep mit itseluf," demurred Carl. "Der copra don'd seem to like der moosic any more as me."

"Probably the snake's fangs have been pulled," put in Burton. "I know the tricks of these snake fakirs."

"He got very good fangs, sahib," declared the Hindoo, dropping the flute and getting up. "He pretty bad snake, hard to handle. Now, watch."

Leaning forward, the Hindoo made a quick grab and caught the snake about the neck with one hand. After whirling it three times around his head, he let it fall on the earth in front of him. To the surprise of the boys and Burton, the cobra lay at full length, rigid and stiff, and straight as a yardstick.

The serpent charmer then walked around the cobra, singing a verse of Hindustani song.

"Jupiter!" exclaimed Burton. "I've heard the Bengal girls chant that song when they went to the well, of an evening, with their water pitchers on their heads. That's the time I was in India after tigers."

"Dekke!" cried the Hindoo; "I have killed my snake, my beautiful little snake! But I have a good cane to walk with."

Then, taking the rigid reptile up by the tail, he pretended to walk with it.

"How you like to buy my cane, sahib?" he asked, swinging the cobra up so that its head was close to the young motorist's breast.

Matt shook his head and stepped quickly back.

"Take the blasted thing away!" snarled McGlory. "Don't get so careless with it."

"The snake's hypnotized," explained Burton. "When he swung it around his head he put it to sleep."

The Hindoo smiled; then, thrusting the head of the rigid snake under his turban, he pushed it up and up until all but the tip of the tail had disappeared under the headdress. After that, with a quick move, he snatched off the turban. The venomous cobra was found in a glittering coil on his head.

With both hands the Hindoo lifted the drowsy cobra from his head, dropped it into the basket, closed the lid, and pushed the peg into place.

"That's a pretty good show," remarked Burton, "but it's old as the hills. Where did you come from?"

"Chicago," replied the snake charmer. "I want a job with Burton Sahib."

"What's your name?"

"Dhondaram."

"There's not a thing I can give you to do in the big show," said Burton, "but maybe the side show could find a place for you. Snake charmers are side-show attractions, anyhow."

Dhondaram was giving most of his attention to Matt, although speaking with Burton.

"He acts as though he knew you, pard," observed McGlory.

Dhondaram must have caught the words, for instantly he shifted his gaze from Matt to the showman.

"Burra Burton can't give me a job in the big show?" he went on.

"No," was Burton's decisive reply. "You're a Hindoo. Tell me, do you know a countryman of yours named Ben Ali?"

Dhondaram shook his head.

"Or Aurung Zeeb?"

Another shake of the head. Dhondaram, seemingly in much disappointment, gathered up his scarlet robe and his basket and started out.

"Know of any one who can handle an elephant?" Burton called after him.

Dhondaram whirled around, his eyes sparkling.

"I handle elephants, sahib," he declared.

"You can?" returned the showman jubilantly. "Well, this is a stroke of luck, and no mistake. Are you good at the job?"

"Good as you find," was the complacent response.

"This elephant's a killer," remarked the showman cautiously.

"He can't kill Dhondaram, sahib," said the Hindoo, with a confident smile.

"He has just been in a tantrum, and threw one man through the tent."

"The elephant, when he is mad, must be looked after with knowledge, sahib."

"Well, you come on, Dhondaram, and we'll see how much knowledge you've got."

Dhondaram dropped in behind Burton, and Matt and his friends fell in behind Dhondaram. Together they repaired to the animal tent.

"Don't like the brown man's looks, hanged if I do, pard," muttered McGlory.

"Me, neider," added Carl. "He iss like der shnake, I bed you—ready to shtrike ven you don't exbect dot. Aber meppy he iss a goot hand mit der elephant. Ve shall see aboudt dot."

When they were back in the animal tent, Burton and the boys found Rajah still in vicious mood. Straining at his chains, the big brute was swaying from side to side, reaching out with his trunk in every direction and trying to lay hold of something.

"Himmelblitzen, vat a ugly feller!" murmured Carl, standing and staring. "He vouldt schust as soon kill somepody as eat a wad oof hay. You bed my life I vas gladt I gave oop trying to manach him."

"There's the elephant, Dhondaram," spoke up Burton, pointing. "He's a killer, I tell you, and I'll not be responsible for damages."

"I myself will be responsible, sahib," answered the Hindoo. "Hold my basket, sahib?" he asked, extending the receptacle toward Carl.

Carl yelled and jumped back as though from a lighted bomb.

"Nod for a millyon tollars!" he declared. "Take id avay."

Dhondaram smiled and placed the basket on the ground; then over it he threw the red robe.

"Dekke, sahibs," he remarked, taking a sharp-pointed knife from a sash about his waist. "Look, and you will see how I manage the elephant in my own country."

Fearlessly he stepped forth and posted himself in front of Rajah. It may be that the angry brute recognized something familiar in the Hindoo's clothes, for he stopped lurching back and forth and watched the brown man.

"You got to be brave, sahibs," remarked the Hindoo, keeping his eyes on the elephant's. "If you have the fear, don't let the elephant see. The elephant is always a big coward, and he make trouble only when he think he got cowards to deal with. Watch!"

With that, Dhondaram stepped directly up to the big head of Rajah. Up went the head, the trunk elevated and curved as though for a blow.

Matt and his friends held their breath, for it seemed certain the brown man would be crushed to death under their very eyes.

But he was not. Rajah's trunk did not descend. In a sharp, authoritative voice Dhondaram began talking in his native tongue. Every word was accompanied by a sharp thrust of the knife.

The huge bulk of the elephant began to shiver and to recoil slowly, releasing the pull on the chains. Presently the big head lowered and the trunk came down harmlessly.

Then, at a word from the Hindoo, the elephant knelt lumberingly on his forward knees, stretching out his trunk rigidly. Dhondaram stepped on the trunk and was lifted, gently and safely, to the broad neck. At another word of command, Rajah rose, and Dhondaram, from his elevated place, smiled and saluted.

"It is easy, sahibs," said he. "This elephant is not a bad one."

Burton clapped his hands.

"Do you want a job as Rajah's mahout?" he asked.

"Yes," was the answer.

The showman turned to Matt.

"Are you willing to take the Comet in the parade with Rajah," he inquired, "now that we have a better driver than even Ben Ali to look after the brute?"

"Dhondaram is a marvel!" exclaimed Matt. "Yes, Burton, we'll be in the parade with the aëroplane."

"Good! Hustle around and get ready. There's not much time. Come down, Dhondaram, and get the blankets on Rajah. The parade will start in half an hour."

The boys hurried out of the tent and into the calliope "lean-to." The Comet had to be put in readiness, and McGlory and Ping, the Chinese boy, had costumes to put on.

MOTOR MATT'S COURAGE.

During the exhibition at Lafayette, Indiana, the Comet had caught fire while in the air and the king of the motor boys had made a dangerous descent in safety. The machine had been damaged, however, and, when the show left the town, Matt and his friends had remained behind to make repairs. These repairs had occupied two days. When they were finished, Matt and McGlory had rejoined the show, flying from Lafayette in the aëroplane and scattering Burton's handbills over the country as they came. Carl Pretzel and Ping, the Chinaman, had caught up with the show by train, there being no place for them on the Comet.

The flight through the air had been made in the face of a tolerably stiff breeze, and Matt and McGlory had found it necessary to lie over almost the entire night on account of a high wind. The flying machine, however, had caught up with the show that very morning.

The Big Consolidated had pitched its tents in the outskirts of Jackson, Michigan, just across the railroad tracks on the road to Wolf Lake.

Matt's work, for which he and his friends were receiving five hundred and fifty dollars a week, was to drive the aëroplane, under its own power, in the parade, and to give two flights daily on the grounds—one immediately after the parade and the other before the evening performance—wind and weather permitting. During these flights Archie Le Bon was carried up on a trapeze under the flying machine.

When the boys reached the place where the aëroplane had been left in charge of Ping, they began at once replenishing the gasoline and oil tanks and seeing that everything was shipshape for the journey on the bicycle wheels.

Ping, while primarily one of the Comet's attendants, had also shown a decided regard for the steam calliope. The calliope operator was teaching him to play a tune on the steam sirens, in return for which attention the Chinaman always provided the musical instrument with the water necessary to make the steam that operated the whistles.

Knowing that he would have to look after the aëroplane, Ping had performed his calliope duties early in the day.

The arrival of Carl with Matt and McGlory was a distinct disappointment to Ping. He and the Dutch boy had had a set-to at the time of their first meeting, and, although Matt had made them shake hands, yet there still rankled in their bosoms a feeling of hostility toward each other. Nevertheless, they kept this animosity in the background whenever Matt or McGlory was near them.

During the trip from Lafayette to Jackson on the train the two had ridden in different cars. They were not on speaking terms when away from Matt King and his cowboy pard.

Carl was just beginning his engagement with the Big Consolidated. He was traveling with the show while waiting for some money to reach him from India. There was nothing for him to do about the Comet, so he secured a job playing the banjo in the side show while a so-called Zulu chief performed a war dance on broken glass in his bare feet.

When the flying machine was in readiness the wagons and riders were already forming for the parade.

"You'll have to hustle to get into your clothes, Joe," said Matt, "you and Ping. Get a move on, now. While you're away I'll watch the Comet."

McGlory and Ping started at once for the calliope tent, which they used as general rendezvous and dressing room. They rode on the machine in costume—McGlory in swell cowboy regalia and Ping in a barbaric get-up that made him look as though he had tumbled off a last year's Christmas tree.

Carl had nothing to do until after the aëroplane flight, and so he remained with Matt until the procession started.

"Here comes dot pad elephant, Racha," murmured Carl, pointing to the string of four elephants lumbering[Pg 7] in their direction from the animal tent. "Der Hintoo iss pooty goot ad bossing der elephant, aber I don'd like his looks."

"He's all right, Carl," laughed Matt easily. "It's Rajah's looks you don't like."

"Vell, I dell you somet'ing, bard. Oof der elephant geds his madt oop, all you got to do is to turn some veels und sail indo der air mit der Gomet."

"We couldn't do that. When the Comet takes to the air she has to have a running start. There's no chance for such a start while we're in the parade."

"So? Vell, keep your eyes shkinned bot' vays und look oudt for yourseluf. I got some hunches alretty dot you vill haf drouples."

"We'll not have any trouble," returned Matt confidently.

A few minutes after the elephants had dropped into line in front of the aëroplane, McGlory, his big spurs clinking at his heels, and Ping, rattling with tin ornaments and spangles, ran toward the Comet. Ping was helped to the upper wing, and Matt and McGlory took their places in the seats on the lower plane.

Carl drew off and cast a gloomy look at Ping, sitting cross-legged on the overhead plane and languidly beating the air with a fan.

"You look like nodding vat I efer see!" whooped Carl, envious to a degree that brought out the sarcastic words in spite of himself.

"My see plenty things likee Dutchy boy when my no gottee gun," chattered Ping.

"Py shinks," rumbled Carl, beside himself, "I vill make you eat dose topacco tags vat you haf on!"

"Makee tlacks," answered Ping, with a maddening wave of the fan; "makee tlacks to side show and plingee-plunk for Zulu man! My makee lide in procesh."

The Chinaman's lordly way worked havoc with Carl's nerves. He howled angrily and rushed forward. At just that moment the parade got under way, and the aëroplane lurched and swayed across the ground toward the road.

"Carl," cried Matt sternly, "keep away!"

The Dutch boy had to content himself with drawing back, shaking his fist at the glittering form on the upper wing of the aëroplane, and saying things to himself.

The parade was but a wearying repetition of the many Matt, McGlory, and Ping had already figured in. The glitter of tinsel, the shimmer of mirrors, the prancing steeds and their mediæval riders, the funny clowns, the camels and elephants, and the blare of the bands had long since lost their glamour. For Matt and his friends the romance had died out, and they were going about their work on a business basis.

The motor boys and their gasoline air ship always commanded attention and were loudly cheered. The fame of Motor Matt's exploits had been told in handbills and dodgers by the clever showman, and, too, Burton had seen to it that the young motorist secured ample space in the newspapers. This, naturally, aroused a great deal of interest, and it had long ago been conceded that Burton's greatest attractions were Matt and his aëroplane.

Rajah was a very good elephant during the entire parade. As usual, his mate, Delhi, marched ahead of him, and always had a pacifying effect. Dhondaram, perched on Rajah's neck, kept the huge brute lumbering in a straight line.

But it seemed strange to Matt and McGlory that Rajah, after his fit of madness, could be so suddenly brought into subjection.

"I'll bet my spurs," remarked McGlory, early in the parade, "that Rajah will cut up a caper yet."

"If he does," answered Matt, "I hope the Comet will be out of his way. But this Dhondaram, Joe, seems to be an A One Mahout, and I believe he can hold Rajah down."

It was about half-past eleven when the dusty paraders began filing back into the show grounds, the cages pulling into the menagerie tent, the riders taking their horses to the stable annex, and Matt driving the aëroplane to the spot from which the first exhibition flight of the day was to be made.

"You and Ping go and peel off your show togs," said Matt to McGlory, as soon as the Comet had been brought to a halt and he and his friends had dropped off the machine, "and then come back and take charge of the start. I've got to fix that electric wiring, or I'll get short-circuited while I'm up with Le Bon."

He pulled off his coat while he was speaking, and dropped coat and hat on the ground; then, as McGlory and Ping made their way toward the calliope tent through a gathering throng of sightseers, the young motorist opened a tool box and stepped around toward the rear of the aëroplane to get at the battery and adjust the connections.

A sharp tent stake, carelessly dropped by one of the show's employees, lay in the way and Matt kicked it aside. He gave a look around, and saw that Dhondaram was having some trouble getting Rajah into the menagerie tent. Thinking nothing of this, Matt proceeded to the rear of the planes and threw himself across the lower wing, close to the motor and the battery.

While he was busily at work he heard a series of startled yells, apparently coming from the crowd that was massing to witness the flight of the Comet. Withdrawing hastily from his place on the lower plane of the machine, Matt dropped to the ground and ran around the ends of the right-hand wings. What he saw was enough to play havoc with the strongest nerves.

Right and left the crowd was scattering in a veritable panic, and through the lane thus made came Rajah, hurling himself along in a direct line for the Comet. There was no one on the animal's back, and the gay trappings which covered him were fluttering and snapping in the wind of his flight.

Rajah had always had a dislike for the aëroplane. Its ungainly form seemed to annoy him. In the present instance this was no doubt a fortunate thing. Had the brute not kept his attention on the air ship, he might have turned on the frightened throng and either killed or injured a dozen people.

Motor Matt knew Rajah was charging the Comet, and the lad's first impulse was to get out of the way; then, reflecting that he and his friends stood to lose the aëroplane unless he made a decided stand of some sort, he caught up the tent stake, which lay near at hand, and jumped fearlessly in front of the flying machine.

This move was not all recklessness on Matt's part. He recalled what Dhondaram had said to the effect that an elephant was a coward, and brave only when he had cowardly human beings to deal with.

Well behind Rajah came a detachment of canvasmen, carrying ropes and iron bars, and one armed with a rifle. The king of the motor boys had seen these men, and he[Pg 8] knew that if he could keep Rajah from his work of destruction until the men had had time to come up the Comet would be saved.

Cries of consternation went up from the spectators as they saw the elephant plunge toward Matt. The lad gave a fierce shout as the brute drew close, and waved the tent stake.

"Get out of the way, King! Out of the way, or you'll be killed!"

This was Burton's voice ringing in Matt's ears, and coming from he knew not where. But the command had no effect on the daring young motorist. He did not move from his position.

Rajah wavered. Although he slackened his headlong rush, he still continued to come on.

When he was close, and Matt could look into his vicious little eyes, he halted, crouched back, and lifted his trunk.

The lad jumped forward and began to use the pointed end of the stake vigorously. Rajah's head was up, and his sinuous trunk twined in the air.

The huge beast towered above Motor Matt like a mountain, but the king of the motor boys held his ground.

DHONDARAM'S EXCUSE.

What might have happened to Matt had not the canvasmen arrived while he was pluckily facing and prodding Rajah, it is hard to say. Certainly the young motorist's brave stand held the elephant at bay and saved the aëroplane. Before Rajah could make up his mind to strike Matt down and trample over him to the Comet, the frenzied brute was assailed on all sides and, under the angry direction of Boss Burton, was beaten into a state of sullen obedience.

"Where's that confounded Hindoo?" roared Burton, as two of the other elephants hauled Rajah off toward the animal tent.

McGlory, in his shirt sleeves, pushed through the crowd and up to the aëroplane in time to hear the question.

"Dhondaram is up there in the calliope tent," said the cowboy; "leastways he was a while ago. When Ping and I dropped into the lean-to to change our togs, the Hindoo was stretched on the floor, groaning like a man who was having a fit. He didn't seem to be so terribly bad off, in spite of the way he was taking on, and I didn't have much time to strip off my puncher clothes and get back here. Just as I got into my regular make-up, and before I could take another look at Dhondaram, a fellow ran by and yelled that Rajah was runnin' wild again and headin' for the Comet. That was enough for me, and I hustled hot foot for here. I saw you, pard," and here the cowboy turned to Matt, "standing off that big brute with a tent stake. Speak to me about that! Say, I'm a Piegan if I ever thought you'd get out of that mix with your scalp."

"It was a fool thing you did, King," growled Burton, very much worked up over the way events had fallen out. "You had about one chance in a hundred of getting out alive. What did you do it for?"

"There wasn't any other chance of saving the Comet," answered Matt, a bit shaken himself now that it was all over and he realized how close a call he had had.

"Your life, I suppose, isn't worth anything in comparison with the value of this aëroplane," scoffed Burton.

"That sort of talk is foolish, Burton," said Matt. "I remembered what Dhondaram had said about not being a coward around Rajah, so I jumped in and got between the elephant and the machine. But there's no use talking now. The aëroplane has been saved, and there's nothing much the matter with me."

"There is some use of talking," snapped Burton. "Here comes Dhondaram, with Ping. Now we can find out how Rajah got away. Dhondaram has starred himself—I don't think. If that's the best he can do, on his first try-out, I might as well give him the sack right here."

The Hindoo and the Chinese boy were coming through the excited crowd toward the aëroplane. Dhondaram staggered as he walked, and there was a wild look in his face.

"What's the matter with you, Dhondaram?" demanded Burton sharply, as the eyes of the little group near the Comet turned curiously on the Hindoo.

"I was sick, sahib," mumbled the brown man, laying both hands on the pit of his stomach and rolling his eyes upward.

"Sick?" echoed Burton incredulously. "It must have come on you mighty sudden."

"It did, sahib. I came in from the parade, then all at once I could not see and grew weak—jee, yes, so weak I could not stay on Rajah's back, but fell to the ground and lay there for a moment, not knowing one thing. When I came to myself I was in a tent, and the feringhi sahib,"—he pointed to McGlory—"and the Chinaman sahib were getting clear of their clothes. When I get enough strength, I come here. Such bhat, sahib. What I say is true."

"You had Rajah properly tamed," went on Burton; "I never saw him act better in the parade than he did this morning. What caused him to make such a dead set at this flying machine the moment you dropped off his back?"

"Who can say, sahib?" asked Dhondaram humbly. "He not like the machine, it may be. Has he a cause to dislike the bird-wagon? The elephant, Burton Sahib, never forgets. A hundred years is to him as a day when it comes to remembering."

One of the canvasmen stepped up and asserted that he had seen Dhondaram drop off Rajah's back and then get up and reel away. Thereupon the canvasman, expecting trouble, called for some of the other animal trainers, and they picked up the first things they could lay hands on and started after the charging elephant.

This was corroborative of the Hindoo's story, as was also the statement made by McGlory.

"Are you subject to attacks like that?" queried Burton, with a distrustful look at the new mahout.

"Not at all, sahib," replied the Hindoo glibly. "It was the first stroke of the kind I have ever suffered. By Krishna, I hope and believe it will be the last."

"Well," remarked Burton grimly, "if you ever have another, you'll be cut out of this aggregation of the world's wonders. Now hike for the menagerie and do your best to curry Rajah down again."

Without a word Dhondaram wheeled and vanished[Pg 9] into the crowd. McGlory turned, caught Matt's arm, and pulled him off to one side.

"What's your notion about this, pard?" he asked.

"I haven't any," said Matt. "It's something to think over, Joe, and not form any snap judgments."

The cowboy scowled.

"These Hindoos are all of the same breed, I reckon," he muttered, "and you know what sort of fellows Ben Ali and Aurung Zeeb turned out to be."

Matt nodded thoughtfully.

"I don't believe one of the turban-tops is to be depended on," proceeded McGlory. "They're all underhand and sly, and not one of 'em, as I size it up, but would stand up a stage or snake a game of faro if he got the chance."

"There you go with your snap judgment," laughed Matt.

"It's right off the reel, anyhow," continued McGlory earnestly. "That Rajah critter was as meek as pie all through the parade. It don't seem reasonable that he'd take such a dead set at the Comet all at once. And, as for Dhondaram getting an attack of cramps, he stood about as much chance of that as of bein' struck by lightning."

Matt was silent.

"Blamed queer," continued McGlory, "that Ben Ali and Aurung Zeeb should drop out, and then, two days after, this other Hindoo should show up. For a happenchance, pard, it's too far-fetched. There's something rotten about it."

"What had Dhondaram got against the Comet?" asked Matt.

"I pass that."

"You're hinting, in a pretty broad way, Joe, that the new mahout deliberately set Rajah on to smash the aëroplane."

"Then I won't hint, pard, but will come out flat-footed. That's just what I think he did."

"Why?"

"You've got to have a reason for everything? Well, I haven't any reason for that, but I think it, all the same."

"Ping!" called Matt.

The Chinese boy was standing by the front of the aëroplane, patting the forward rudders affectionately, looking at the machine with a fond eye, and apparently exulting over the fact that it had been saved from destruction.

At Matt's call, the boy whirled around and ran toward his two friends.

"Whatee want, Motol Matt?" he asked.

"You came here with the Hindoo," said Matt. "How was that?"

"My follow Hindoo flom tent. Him no gettee sick. My savvy. When McGloly makee lun flom tent, Hindoo jump to feet chop-chop, feel plenty fine. Him makee play 'possum. Whoosh! When him come, my come, too."

"Talk about that!" exclaimed McGlory. "Worse, and more of it. There's a hen on of some kind, pard."

"Ping," proceeded Matt, "I've got a job for you."

"Bully!" cried the Chinaman delightedly.

"What I want you to do," said Matt, "is to watch Dhondaram. Don't let him see you at it, mind, but just dodge around, keep tab on him, and don't let him suspect what you're doing."

"Hoop-ala!" said Ping, delighted at having such a piece of work come his way.

"Think you can attend to that?"

"Can do! You bettee. My heap smarter than Hindoo. You watchee, find um out."

"All right, then. Away with you."

Ping darted off toward the animal tent. At that moment Burton hurried up.

"Better get busy and make your ascent, Matt," said Burton. "The crowd's all worked up about that elephant business, and the quickest way to get the people's minds off it is by giving them something else to watch and talk about."

"I'll start at once," replied Matt, taking his seat in his accustomed place on the lower plane. "Let her flicker, Joe."

The king of the motor boys "turned over" the engine, switched the power into the bicycle wheels, and the Comet, pushed by McGlory and half a dozen canvasmen, raced along the hard ground for a running start.

ROBBERY.

Motor Matt made as graceful an ascent and as pretty a flight in the aëroplane as any he had ever attempted. Archie Le Bon, swinging below the machine on a trapeze, put the finishing touch to the performance by doing some of the most hair-raising stunts. Loud and prolonged were the cheers that floated up to the two with the Comet, and there was not the least doubt but that the aëroplane had successfully diverted the minds of the spectators from the recent trouble with Rajah.

After the Comet had fluttered back to earth, and the crowd had drifted away toward the side show, Matt and McGlory left a canvasman in charge of the machine and dropped in at the cook tent for a hurried meal. There was now nothing for the two chums to do until the next flight of the day, which was billed to take place at half-past six.

"Did you ever have a feeling, pard," said the cowboy, as he and Matt were leaving the mess tent and walking across the grounds toward the calliope "lean-to," "that there was a heap of trouble on the pike, and all of it headed your way?"

"I've had the feeling, Joe," laughed Matt.

"Got it now?"

"No."

"Well, I have."

McGlory halted and looked skyward, simultaneously lifting his handkerchief to test the strength and direction of the wind. Watching the weather had become almost a second nature with the cowboy since he and Matt had been with the Big Consolidated. Aëroplane flights are, to a greater or less extent, at the mercy of the weather, and the more wind during an ascension then the greater the peril for Motor Matt.

"Think the weather is shaping up for a gale this afternoon, Joe?" queried Matt.

"Nary, pard. There's not a cloud in the sky, and it's as calm a day as any that ever dropped into the almanac."

"Not exactly the day to worry, eh?"

"Well, no; but I'm worrying, all the same. What are you going to do now?"

"Catch forty winks of sleep in the calliope tent. We didn't get our full share of rest last night, and I'm feeling the need of it."

When they got to the "lean-to" Matt laid a horse blanket on the ground, close to the wheels of the canvas-covered calliope, and stretched himself out on it. A band was playing somewhere about the grounds, and the sound lulled him into slumber.

The cowboy was not sleepy, and he was too restless to stay in the "lean-to." Matt was hardly asleep before McGlory had left on some random excursion across the grounds.

A man entered the calliope tent. He came softly, and halted as soon as his eyes rested on the sprawled-out form of Motor Matt.

The man was Dhondaram. A burning light arose in the dusky eyes as they continued to rest on the form of the sleeper.

For some time the doors leading into the "big show" had been open. Crowds were entering the menagerie tent, and passing from there into the "circus top." The noise was steady and continuous, so that it was impossible for Matt, who was usually a light sleeper, to hear the entrance of the Hindoo.

Dhondaram lingered for several minutes. He had not his flat-topped basket with him, and he whirled abruptly and hurried out of the "lean-to."

From the look that flamed in the face of the Hindoo as he left, it seemed as though he was intending to return again—and to bring the cobra with him.

He had not been gone many minutes, however, when Boss Burton entered the calliope tent. This was where he usually met the man from the ticket wagon, as soon as the receipts had been counted and put up in bags, received the money, and carried it to the bank. This part of the work had to be accomplished before three o'clock in the afternoon, as the banks closed at that hour. The money from the evening performance always accompanied Burton in the sleeping car on the second section of the show train, and was deposited in the next town on the show's schedule.

Burton did not see Matt lying on the ground, close up to the calliope, and seated himself on an overturned bucket and lighted a cigar. The weed was no more than well started, when Dhondaram, carrying his basket, appeared softly in the entrance. At sight of Burton, the Hindoo stifled an exclamation and came to a startled halt.

"What's wrong with you?" demanded the showman.

"Nothing at all, sahib," answered Dhondaram, recovering himself.

"Feeling all right now?"

"Yes, sahib."

"Good!"

Without lingering for further talk, Dhondaram faced about and glided away.

The conversation between the showman and the Hindoo had awakened Matt. The young motorist sat up blinking and looked at Burton. He knew how the proprietor of the Big Consolidated always met the ticket man in the calliope tent, about that time in the afternoon, and checked up and received the proceeds for deposit in the local bank.

"Much of a crowd, Burton?" called Matt.

"Oh, ho!" he exclaimed. "You've been taking a snooze, eh?"

"A short one. Trying to make up for a little sleep I lost last night. What time is it, Burton?"

"About half-past two. Say," and it was evident from Burton's manner that the thought flashing through his brain had come to him suddenly, "I want to talk with you a little about that Dutch pard of yours."

"Go ahead," said Matt, leaning back against one of the calliope wheels; "what about Carl?"

"Is he square?" continued Burton.

"Square?" repeated Matt. "Why, he's as honest a chap as you'll find anywhere. If he wasn't, he wouldn't be training with McGlory and me. You ought to know that, Burton."

"You ain't infallible, I guess. Eh, Matt? You're liable to make mistakes, now and then, just like anybody else."

"I suppose so, but I know Carl too well to make any mistake about him. What gave you the idea he was crooked?"

"I never had the idea," protested Burton. "I just asked for information, that's all. He came to the show on your recommendation, and I've taken him in, but I like to have a line on the people I get about me."

"There's more to it than that," said Matt, studying Burton's face keenly. "Out with it, Burton."

"Well, then, I don't like the Dutchman's looks," acknowledged Burton. "Ping told me——"

"Oh, that's it!" muttered Matt. "Ping told you—what?"

"Why, that he caught the Dutchman going through his pockets last night. If that's the kind of fellow Carl is, I——"

"Take my word for it, Burton," interrupted Matt earnestly, "my Dutch pard is on the level. He makes a blunder, now and then, but he's one of the best fellows that ever lived."

"What did Ping talk to me like that for?"

"He and Carl don't hitch. There's a little petty rivalry between them, and they're a bit grouchy."

"Is Ping so grouchy that he's trying to make people believe Carl's a thief?"

"Ping is a Chinaman, and he has his own ideas about what's right and wrong. I'll talk to him about this, though."

"You'd better. Certainly you don't want one of your pards circulating false reports about another." Burton looked at his watch impatiently. "I wonder where Andy is?" he muttered, "He's behindhand, now, and if he delays much longer, I'll not be able to get to the bank before closing time."

"He may have had such a big afternoon's business," suggested Matt, "that it's taking him a little longer to get the money counted, and into the bags."

"The business was only fair—nothing unusual. Andy has had plenty of time to sack up the money and get here with it."

Andy Carter was the ticket man. He was middle-aged, an expert accountant, and was usually punctual to the minute in fulfilling his duties to his employer.

"Have you seen anything of Dhondaram lately?" Matt inquired casually.

"He blew in here with his little basket just before you woke up. Didn't you see him?"

"I heard you talking," answered Matt, "and that's what wakened me, but I didn't see who you were talking with. Did he get Rajah under control again, Burton?"

A puzzled look crossed the showman's face.

"He can manage that big elephant as easily as I can manage a tame poodle, and he wasn't two minutes with the brute before he had him as meek as Moses. What I can't understand is how Rajah ever broke away and went on the rampage like he did."

"There are others on this ground who deserve your suspicions a whole lot more than my Dutch pard," observed Matt.

"You mean that I'd better be watching Dhondaram?"

"Not at all," was the reply. Matt was already having the Hindoo watched, so it was hardly necessary for Burton to attend to the matter. "The Hindoo's actions are queer."

"Hindoos are a queer lot, anyhow. But they're good elephant trainers, and that's the point that gets me, just now."

"Where did Dhondaram say he——"

Motor Matt got no further with his question. Just at that moment a man reeled through the entrance. His hat was gone, his coat was torn, and there was a bleeding cut on the side of his face. With a gasp, he tumbled to his knees in front of Burton.

"Great Jupiter!" exclaimed Burton, leaping to his feet. "Andy! What's happened to you?"

"Robbed!" breathed the ticket man, swaying and holding both hands to his throat; "knocked down and robbed of two bags of money that I was bringing here. I—I——"

By then the startled Matt was also on his feet.

"Who did it?" shouted the exasperated Burton. "Did you see who did it? Speak, man!"

But Carter was unable to speak. Overcome by what he had passed through, he crumpled down at full length and lay silent and still at the showman's feet.

BETWEEN THE WAGONS.

Excitement, and a certain reaction which follows all such shocks as the ticket man had been subjected to, had brought on a fainting spell. A little water soon revived Carter, and he was laid on the blanket from which Matt had gotten up a little while before.

"Now tell me about the robbery," said Burton, "and be quick. While we're wasting time here, the thieves are getting away. I can't afford to let 'em beat me out of the proceeds of the afternoon's show. Who did it, Carter?"

"I don't know, Burton," was the answer.

"Don't know?" repeated the showman blankly. "Can't tell who knocked you down and lifted the two bags, when it was done in broad day! What are you givin' us?" he added roughly.

"It's a fact, Burton," persisted Carter. "I was hit from behind and could not see the man who struck me."

"You've got a cut on your face. How do you account for that if, as you say, you were struck from behind?"

"The blow I received threw me forward against a wagon wheel. The tire cut my cheek. I dropped flat, and didn't know a thing. When I came to myself, of course, the money was gone."

"Here's a pretty kettle of fish, and no mistake!" fumed Burton. "How much money did you have, Andy?"

"A little over eighteen hundred dollars."

"Eighteen hundred gone to pot! By Jupiter, I won't stand for that. Can't you think of some clue, Andy? Pull your wits together. It isn't possible that a hold-up like that could take place in broad day without leaving some clue behind. Think, man!"

"Maybe that new Dutch boy could give you a clue," replied Carter. "He's a friend of Motor Matt's, isn't he?"

"He's a pard of Matt's," said Burton, casting a significant look at the king of the motor boys. "What makes you think he might give us a clue? Don't hang fire, Andy! Every minute we delay here is only that much time lost. Go on—and speak quick."

"I had just left the ticket wagon," pursued Carter, trying to talk hurriedly, "when the Dutchman stepped up to me. He wanted a word in private, as he said, and I told him he'd have to wait until some other time. He said he couldn't wait, and that what he had to tell me was important. I couldn't get away from him, and I agreed to listen to what he had to say providing he didn't delay me more than two or three minutes. With that, he led me around back of the "circus top" and in between two canvas wagons. That's when I got struck from behind."

Motor Matt listened to this in blank amazement. Boss Burton swore under his breath.

"It's a cinch the Dutchman had a hand in the robbery," the showman declared. "He lured Andy in between the wagons, and it was there that some of the Dutchman's confederates knocked Andy down and lifted the bags. If we can lay hands on this Carl, we'll have one of the thieves."

"Don't be too sure of that," interposed Matt. "Carl Pretzel never did a dishonest thing in his life, and I'm sure he can explain this."

"Don't let your regard for the Dutchman blind you to what's happened, Matt," warned the showman. "The only thing he asked Andy to go in between the wagons for was so that the dastardly work would be screened from the eyes of people around the grounds." He turned away, adding: "We'll have to hunt for Carl—and it will be a hunt, I'll be bound. Unless I miss my guess, he and his confederates are a good ways from here with that eighteen hundred dollars."

Burton ran toward the tent door, followed by Matt. Before either of them could pass out, Carl and McGlory stepped through and stood facing them.

Carl had a red cotton handkerchief tied round the back of his head.

"Here he is, by thunder!" cried the surprised Burton.

"So, you see," spoke up Matt, "he didn't run away, after all."

"It's some kind of a bluff he's working," went on Burton doggedly. "I want you," he added, and dropped a heavy hand on Carl's shoulder.

"For vy iss dot?" inquired Carl.

"What do you want the boy for?" said McGlory.

"He helped steal eighteen hundred dollars the ticket man was bringing over here for me to take to the bank," said Burton; "that's what I want him for."

"Iss he grazy?" gasped Carl, falling weakly against McGlory. "Vat dit I do mit der money oof I took it, hey? Und ven dit I take it, und vere it vas? By shinks,[Pg 12]" and Carl rubbed a hand over his bandaged head, "I'm doing t'ings vat I don'd know nodding aboudt. Somepody blease tell me vat I peen oop to."

"Don't you get gay," growled Burton. "It won't help your case any."

"Give me the straight o' this," demanded McGlory.

Burton stepped back and waved a hand in the direction of Andy Carter.

"Look at Andy!" he exclaimed. "He's been beaten up and robbed of two bags of money that he was bringing here. The Dutchman lured him in between a couple of canvas wagons, and that's where the job was pulled off."

"Speak to me about this!" murmured the dazed McGlory. "What about it, Matt?" he added.

Matt did not answer, but stepped over to Carl.

"Why did you ask Carter to step in between the wagons, Carl?" the young motorist asked.

"Pecause I vanted to shpeak mit him alone by himseluf," answered Carl. "Vat's der odds aboudt der tifference, anyvay?"

"What did you want to speak with him about?"

"Vell, I don'd like blaying der pancho for dot Zulu feller. I dit id vonce, und den fired meinseluf. Vat I vant iss somet'ing light und conshenial—hantling money vould aboudt suit me, I bed you. Dot's vat I vanted to see der ticket feller aboudt. I vanted to ask him vould he blease gif me some chob in der ticket wagon, und I took him off vere ve could haf some gonversations alone. Dot's all aboudt it, und oof I shtole some money, vere it iss, und vy don'd I got it? Tell me dot!"

"That's a raw bluff you're putting up," scowled Burton. "You're nobody's fool, even if you do try to make people think so."

"I ain't your fool, neider," cried Carl, warming up. "You can't make some monkey-doodle pitzness oudt oof me. You may own der show und be a pig feller, aber I got some money meinseluf oof it efer geds here from Inchia, so for vy should I vant to svipe your money, hey?"

"What happened between the wagons, Carl?" went on Matt. "Just keep your ideas to yourself, Burton," he added, "and don't accuse Carl until he has a chance to give his side of the story. Did you see the man who knocked Carter down?"

"I don'd see nodding," said Carl.

"Do you mean to say," asked Carter, rising up on the blanket, "that I wasn't knocked down?"

"I don'd know vedder or nod you vas knocked down. How could I tell dot?"

"You were there with Carter—there between the wagons," cried Burton angrily. "Why shouldn't you have seen what happened?"

"Look here vonce."

Carl pulled off his cap and bent his head.

"Feel dere," he went on, touching the back of his head. "Be careful mit your feelings, oof you blease, und tell me vat you findt."

"A lump," said Matt.

"Ouch!" whimpered Carl. "It vas so sore as I can't tell. My headt feels like a parrel, und hurts all ofer. Dot's der reason I ditn't see vat habbened. I vas knocked down meinseluf, und it must haf peen aboudt der same time der dicket feller keeled ofer."

"There you have it, Burton," said Matt, facing the showman. "Carl wanted a job in the ticket wagon, and thought he might get it by talking with Andy Carter. When they got in between the wagons they were both knocked down."

"Rot!" ground out Burton. "Why didn't Carter see the Dutchman when he came to? Or why didn't the Dutchman see Carter, if he got back his wits first?"

"Carl was looking for Carter when I met up with him," put in McGlory.

"The Dutchman wasn't near the wagons when I recovered my senses," came from the ticket man.

"Und I don'd know vedder you vas dere or nod, Carter," explained Carl. "Ven I got to know vere I vas at, I foundt meinseluf vanderin' around mit a sore headt. But I tell you somet'ing, Burton. I peen a tedectif, und a fine vone. How mooch you gif me oof I findt der t'ieves und recofer der money? Huh?"

"I believe you know where that money is, all right," declared the showman, "and if you think I'm going to pay you something for giving it back, you're wrong. If you want to save yourself trouble, you'll hand over the funds."

"You talk like you vas pug-house!" said Carl. "I ain't got der money."

"Who helped you steal it?"

"Nopody! I ditn't know it vos shtole ondil you shpeak aboudt it."

"Stop that line of talk, Burton," put in Matt. "Carl's story is straight, and it satisfies me."

"How much money did the Dutchman have when he came here this morning?" asked Burton.

"T'irty cents," replied Carl. "Modor Matt paid my railroadt fare from Lafayette to Chackson."

"Search him, McGlory," ordered Burton. "Let's see if he has anything about his clothes that will prove his guilt."

Carl began to laugh.

"What's the joke?" snorted Burton.

"Vy," was the answer, "to t'ink I haf eighdeen huntert tollars aboudt me und don't know dot. Go on mit der search, McGlory."

Carl lifted his hands above his head, and the cowboy began pushing his hands into Carl's pockets. In the second pocket he examined he found something which he pulled out and held up for the observation of all. It was a canvas sack, lettered in black, "Burton's Big Consolidated Shows."

"One of the bags that held the money!" exclaimed Carter.

"I told you so!" whooped Burton.

Matt and McGlory were astounded. And so was Carl—so dumfounded that he was speechless.

A PEG TO HANG SUSPICIONS ON.

"Vell, oof dot don'd grab der banner!" mumbled Carl, when he was finally able to speak. "I hat dot in my bocket und don'd know nodding aboudt it! Somepody must haf put him dere for a choke."

"That's a nice way to explain it!" growled Burton. "It cooks your goose, all right. Anything in the bag, McGlory?"

"Nary a thing," answered the bewildered cowboy, turning the bag inside out.

"Go on with the search," ordered Burton.

Mechanically the cowboy finished looking through the Dutch boy's clothes, and all the money he found consisted of two ten-cent pieces and a couple of nickels.

"Where did you hide that money?" demanded Burton sternly, stepping in front of Carl.

"I don'd hite it no blace," cried Carl. "You make me madt as some vet hens ven you talk like dot. Ged avay from me or I vill hit you vonce."

"Carter," went on Burton in a voice of suppressed rage, "call a policeman."

The ticket man had scrambled to his feet, and he now made a move in the direction of the tent door.

"Hold up, Carter!" called Matt; then, turning to Burton, he went on: "You're not going to arrest Carl, Burton, unless you want this outfit of aviators to quit you cold."

The red ran into Burton's face.

"Are you trying to bulldoze me?" he demanded. "I've got eighteen hundred dollars at stake, and I'm not going to let it slip through my fingers just because you fellows threaten to leave the show and take the aëroplane with you. I tell you frankly, King, I don't like the way you're talking and acting in this matter. We've got good circumstantial evidence against your Dutch friend, and he ought to be locked up."

"I admit that there's some evidence," returned Matt, "but you don't know Carl as well as I do. It isn't possible that he would steal a nickel from any one. If there was ten times as much evidence against him, no one could make me believe that."

"You're allowing your friendship to run away with your better judgment. What am I to do? Just drop this business, right here?"

"Of course not. All I want you to do is to leave Carl alone and let the motor boys find the thief."

"I want that money," said Burton, with a black frown, "and I'm satisfied this Dutchman knows where it is."

"And I'm satisfied he doesn't know a thing about it," said Matt warmly.

"How did that bag get into his pocket?"

"If you come to that, why isn't there some of the stolen money in the bag? Do you think for a minute, Burton, that Carl would be clever enough to plan such a robbery, and then be foolish enough to carry around with him the bare evidence of it? You don't give him credit for having much sense. Why should he keep the bag, and then come in here with it in his pocket?"

Burton remained silent.

"Furthermore," proceeded Matt, "if Carl is one of the thieves, or the only thief, why did he come in here at all? Why didn't he make a run of it as soon as he got his hands on the money?"

"Every crook makes a mistake, now and then," muttered Burton. "If they didn't, the law would have a hard time running them down."

"I'll tell you what I'll do," said Matt. "Leave Carl alone. If I can't prove his innocence to your satisfaction, I'll agree to stay four weeks with your show for nothing. You'll be making more than two thousand dollars, and you've only lost eighteen hundred by this robbery."

Burton's feelings underwent a change on the instant.

"Oh, well, if you put it that way," he said, "I'm willing to let the Dutchman off. I only want to do the right thing, anyhow."

"You vas a skinner," averred Carl contemptuously. "I knowed dot from der fairst time vat ve met."

"Sing small, that's your cue," retorted Burton. "Remember," and he whirled on Motor Matt, "if you don't prove the Dutchman's innocence, you're to work for me for four weeks without pay. I'm willing to let it rest in that way."

With that Burton took himself off. His show was doing well and he was not pressed for funds. As for the rest of it, he had shifted everything connected with the robbery to the shoulders of Motor Matt.

McGlory was a bit dubious. He had not known Carl as long as Matt had, and had not the same amount of confidence in him.

"Matt," remarked the Dutch boy with feeling, "you vas der pest friendt vat I efer hat, und you bed my life you don'd vas making some misdakes ven you pelieve dot I ditn't shdeal der money. I don'd know nodding aboudt der pag, nor how it got in my bocket. Dot's der trut'."

"I know that without your telling me, pard," said Matt. "The thing for us to do now is to find out who the real thieves are."

"There must have been only one," said McGlory.

"There must have been two, Joe."

"How do you figure it?"

"Why, because both Carl and Carter were knocked down at the same time. Neither saw what had happened to the other. Two men must have done that."

"Vat a headt it iss!" murmured Carl. "Modor Matt vould make a fine tedectif, I tell you dose."

"You've got a bean on the right number, pard, and no mistake," exulted McGlory.

"Did you see any one near the wagons when you led the ticket man in between them?" asked Matt, turning to look at the place where he had last seen the ticket man standing.

But Carter had left. Presumably, he had followed after Burton.

"I don'd see nopody aroundt der vagons," answered Carl. "Der t'ieves vas hiding, dot's a skinch. Day vas hid avay mit demselufs in blaces vere dey couldt handt Carter und me a gouple oof goot vones. Ouch again!" and Carl rubbed a gentle hand over the red cotton handkerchief.

"Take us to the place where you and Carter were knocked down, Carl," said Matt. "We'll look the ground over and see if we can find anything."

The Dutch boy conducted his two friends toward the rear of the circus tent. Here there were two big, high-sided canvas wagons drawn up in a position that was somewhat isolated so far as the tents of the show were concerned. The wagons had been left in the form of a "V," and Carl walked through the wide opening.

"Dis iss der vay vat ve come in," said he, "I in der lead oof der dicket man. Ven I ged py der front veels oof der vagon, I turn around, und den—biff, down I go like some brick puildings had drowed demselufs on dop oof me. Shiminy grickeds, vat a knock! I don'd know vere Carter vas shtanding, pecause I ditn't see him, I vas hit so kevick."

Matt surveyed the ground. The turf had retained no[Pg 14] marks of the violent work. He examined the rear tires of the wagons. The rims, for the whole of their circumference that was off the ground, were covered with a coating of dried mud; and this caking of mud was not broken at any place.

"Carter must have stood here, in this position," observed Matt, placing himself between the two rear wheels. "He says that he fell against one of the wheels and cut his cheek on the tire. I can't find any trace of the spot where Carter came into such rough contact with either of the tires."

"Don't you think he was telling the truth, pard?" asked McGlory in some excitement. "Is it possible he was using the double tongue, just to——"

"Easy, there," interrupted Matt. "Carter was dazed when he fell, and could hardly have known whether he struck against the tire or against something else. He may have dropped on a stone——"

"No stones here," objected McGlory, with a quiet look over the surface of the ground.

"Well, then it was something else that caused the injury to his cheek. He——"

"Here's something," and McGlory made a dive for the ground and lifted himself erect with an object in his hand. "I reckon it don't amount to anything, though."

"Let's see it," said Matt.

McGlory handed the object to the young motorist. It was a peg, perhaps half an inch thick by three inches long, and had a knob at one end as big as a marble.

"Great spark-plugs!" exclaimed the king of the motor boys, staring from the peg to McGlory and Carl.

"What's to pay?" queried McGlory. "You act as though we'd found something worth while."

"We have," declared Matt, "and everything seems to be helping us on toward a streak of luck in this robbery matter."

"How vas dot?" queried Carl.

"This peg belongs to the Hindoo," said Matt. "It's the contrivance he used for fastening down the lid of that flat basket in which he carries the cobra."

McGlory went into the air with a jubilant whoop.

"He's the thief!" he cried. "I've had a feelin' all along that he was a tinhorn. This proves it! Sufferin' blackguards, Matt, but you've got a head!"

"Vere iss der shnake?" came from Carl, as he looked around in visible trepidation. "Oof der pasket iss oben, den der copra is loose on der grounds. Vat a carelessness!"