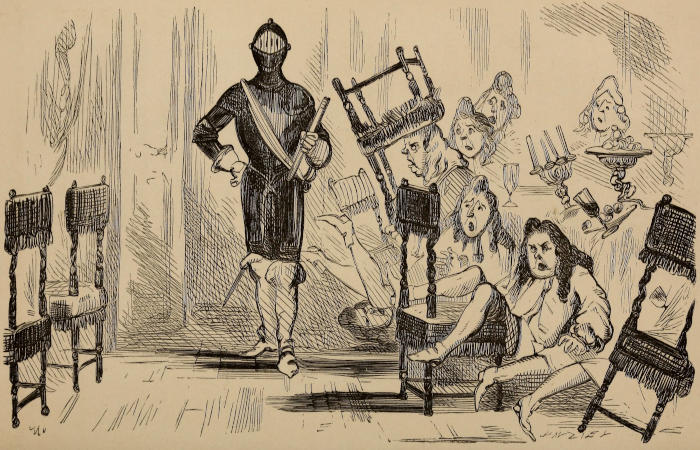

MAUDE ALLINGHAME.—p. 19.

Front.

MIRTH AND METRE.

MIRTH AND METRE—p. 80.

LONDON AND NEW YORK:

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & CO.

1855.

MIRTH AND METRE.

BY

TWO MERRY MEN.

Frank E. Smedley,

AND

Edmund H. Yates.

“I’D RATHER HAVE A FOOL TO MAKE ME MERRY, THAN EXPERIENCE

TO MAKE ME SAD.”—SHAKSPEARE.

With Illustrations by M’Connell.

LONDON:

GEO. ROUTLEDGE & CO., FARRINGDON STREET.

NEW YORK: 18, BEEKMAN STREET.

1855.

If any one of those mysterious autocrats who “do” the reviews “on” some newspaper or serial shall, in his condescension, deign to inform public opinion what he may think about Mirth and Metre, that autocrat, unless he be in an unhoped-for state of benignity, will, doubtless, commence with the agreeable remark that “the work before us consists of certain Lays and Legends, written in paltry imitation of the productions of the inimitable Thomas Ingoldsby.”

Admitting the imputation without cavil, (except at the word “paltry,” which really is too bad, don’t you think so, dear reader?) the authors would inquire whether such an admission legitimately exposes them to hostile criticism? When the late Mr. Barham produced the “Ingoldsby Legends,” he, as it were, founded a new school of comic versification. That this is not a mere ipse dixit of our own is evinced by the fact that, in common parlance, a man who adopts this style of composition is said to have written an “Ingoldsby,” as he might be said to have written an Epic, had he chosen that form instead.

To assert that only a very small shred of Mr. Barham’s mantle has fallen upon any of his imitators (a fact to which none will more readily assent than the present writers), is simply to state that the standard we have proposed to ourselves is a high one, and proportionately difficult to attain.

is a fact which does not appear to have checked the energies or paralysed the ambition of the “king of men;” nor was Waterloo the less a great victory because Julius Cæsar had a few centuries before successfully invaded Gaul.

To our thinking, however, the common sense of the matter lies (after the usual fashion of that inestimable quality) in a nutshell. A servile copy of any particular style—a hash of old ideas, or want of ideas, served up after the manner of some popular writer—is a bad thing, against which all true lovers of literature are bound to raise their voices whenever they meet with it; but if a young author, imbued with admiration of, and respect for, some man of genius who has lived before him, sees fit to embody his own thoughts and feelings in a form which experience has approved, rather than confuse himself and his readers, in his frantic strivings after originality, by torturing words out of their natural meaning, and marshalling them in a metre against which the ear rebels, we conceive no just canon of criticism can forbid his doing so. To which of these categories the Lays and Legends in this Volume are to be assigned, we leave it to our readers to determine.

Frank E. Smedley.

Edmund H. Yates.

| PAGE | |

| MAUDE ALLINGHAME; A LEGEND OF HERTFORDSHIRE. BY FRANK E. SMEDLEY | 1 |

| “YE RIGHT ANCIENT BALLAD OF YE COMBAT OF KING TIDRICH WITH YE DRAGON.” BY FRANK E. SMEDLEY | 23 |

| ST. MICHAEL’S EVE. BY EDMUND H. YATES | 31 |

| THE KING OF THE CATS; A RHINE LEGEND. BY EDMUND H. YATES | 38 |

| THE LAPWING. BY EDMUND H. YATES | 43 |

| THE ENCHANTED NET. BY FRANK E. SMEDLEY | 45 |

| A FYTTE OF THE BLUES. BY FRANK E. SMEDLEY | 53 |

| THE FORFEIT HAND; A LEGEND OF BRABANT. BY FRANK E. SMEDLEY | 55 |

| SIR RUPERT THE RED. BY EDMUND H. YATES | 71 |

| COUNT LOUIS OF TOULOUSE. BY EDMUND H. YATES | 82 |

| ANNIE LYLE. BY EDMUND H. YATES | 84 |

| JACK RASPER’S WAGER; OR, “NE SUTOR ULTRA CREPIDAM.” BY EDMUND H. YATES | 86 |

| THE OVERFLOWINGS OF THE LATE PELLUCID RIVERS, ESQ. BY EDMUND H. YATES | 94 |

Frank E. S.

[1] The following legend is founded on a story current in the part of Herts where the scene is laid; the house was actually burnt down about ten years ago, having just been rendered habitable.

[2] The name of a lonely common near Harpenden, formerly a favourite site for prize-fights.

Frank E. S.

[Should any reader wish to learn more of the various personages here mentioned, we refer him to the “Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, from the earlier Teutonic and Scandinavian Romances,” to which we are indebted for our information on the subject.]

[3] King Tidrich, Dietrich, or Theoderic, the son of Thietmar, king of Bern, and the fair Odilia, daughter of Essung Jarl, was, as it were, the central hero of that well-known, popular, and interesting work the “Book of Heroes,” which relates the deeds of the champions who attached themselves to him, and the manner in which they joined his fellowship.

[4] Tidrich of Bern was also king of Aumlungaland (Italy); he espoused Herraud, daughter of King Drusiad, a relation of Attila.

[5] These three champions were among the eleven heroes who accompanied Tidrich in his memorable expedition to contend against the twelve guardians of the Garden of Roses at Worms.

[6] They had a weakness for naming swords in those days, just as in the nineteenth century we delight in bestowing euphonious titles on “villa residences,” puppy dogs, and men-of-war!

[7] Sigurd, or Siegfried, son of Sigmond, king of Netherland, is the chief hero of the Nibelungen Lay. There are various accounts of his death, one of the least improbable supposes him to have been destroyed by a dragon.

E. H. Y.

ST. MICHAEL’S EVE.—p. 36.

E. H. D.

E. H. D.

Frank E. S.

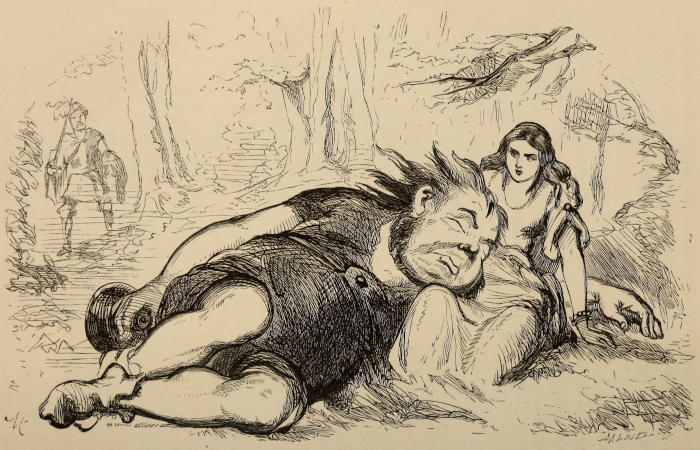

THE ENCHANTED NET.—p. 51.

Frank E. S.

DE RODON.

Heraldic work furnished to order.

Frank E. S.

[8] The facts (?) of this Legend are taken, by poetical licence, from “Legends of the Rhine,” by the author of “Highways and Byways.”

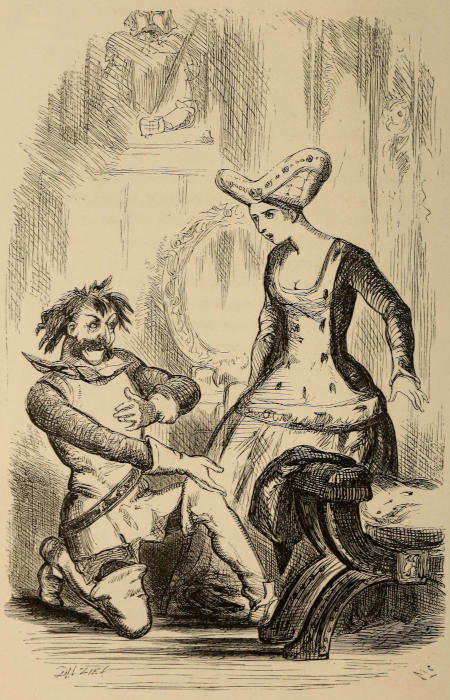

THE FORFEIT HAND.—p. 60.

E. H. Y.

SIR RUPERT THE RED—p. 79.

E. H. Y.

E. H. Y.

E. H. Y.

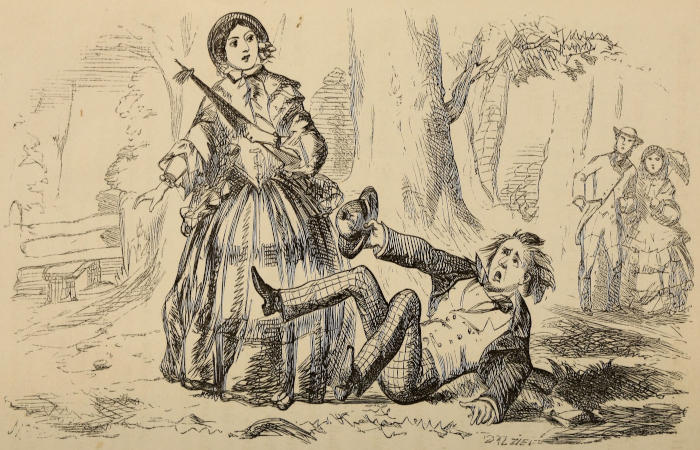

JACK RASPER’S WAGER.—p. 92.

In submitting to the public some of the productions of my lamented friend Rivers, I think it right to endeavour to sketch some faint outline of the career of their illustrious author. “The world knows nothing of its greatest men,” says Philip Van Artevelde, and its general ignorance of Rivers clearly proves the truth of the remark.

Born of poor but respectable parents, in the parish of St. Pancras, at an early age Rivers evinced symptoms of that poetic talent which, in later life, made him so renowned—I mean, which would have made him so renowned, had he not been crushed by the wretched blindness and illiberality of the publishers of the metropolis. He could not have been more than five years of age when he first burst forth in metrical numbers; it was at the family dinner-table, when, pointing first to the smoking joint, then to the domestic implement by which he was conveying a portion of it to his mouth, he exclaimed—

A moment after, indicating the beer jug, his juvenile “poet’s eye, in a fine frenzy rolling,” he continued, “chalk!” His meaning on this point was vague, but it is generally considered he implied that the liquid was not paid for at the time, but was chalked up behind the door to the family account—a custom prevalent, I have ascertained, in many parts of the United Kingdom. From that period until his death he was constantly engaged in writing;—though his[95] name never appeared to any of his productions, they were most extensively read; indeed, one of his minor poems—

has been considered so successful, that the publication of it is annually revived, and the fourteenth of February, sacred to St. Valentine, is the day usually chosen for its reappearance.

For the last twenty years of his life, poor Rivers laboured under severe fits of melancholy and depression, the cause of which he long held secret. Shortly before his decease, however, he confided to me the source of his grief. It was, that manuscripts which he had forwarded on approval to various publishers, had been returned as worthless, while a few months afterwards the same publishers would send forth books of poems in which the most direct plagiarisms from my poor friend’s productions would appear. He made me solemnly pledge myself to see him righted in the opinion of the world, and hence the publication of these papers.

I regret exceedingly to be obliged to hold up to public odium names which have hitherto stood so highly as those of Mr. A—f—d T—ys—n and his publisher, Mr. M—x—n, but I defy any candid reader to peruse the following vigorous and striking stanzas of my poor friend’s, and then turn to that weak and rambling production, “L—cks—y H—ll,” without perceiving which is the grand original, which the mean and despicable parody!

Such is the noble ballad of Vauxhall! but Rivers was master of all styles. The following exquisite picture of the joys and sorrows of modern domestic life presents an example of that happy blending[99] of the real and the romantic with which the head of Rivers overflowed. The ballad of “Boreäna” has been kindly communicated by my literary friend Frank Fairleigh, who knew, loved, and admired Rivers as much as myself. After pointing out some of the more subtle and mysterious beauties of this matchless lyric, Fairleigh adds, “and yet after this, A—f—d T—ny—n had the face to publish that bombastic, trashy ballad of “Oriana,” and pretend it was original; where does that misguided man expect to go to?”

My poor friend had always within him a certain classical fondness of the ancient style of poetry; none of your vulgar Alcaics and Sapphics—“These,” he used to remark, “Horace, Tibullus, or any fellow of that calibre could manage; but the glorious hexameters and pentameters of Homer, Virgil, and Ovid,—they’re the things, my boy!” His delight in this species of composition was so great that at school we used to call him, as a nickname, “Professor Long-and-short-fellow.” It curdles my blood to think that some obscure person in America, who has latterly been indulging in dactyllic and spondaic metre, has dared to name himself[102] partly in imitation of the sobriquét by which we designated our friend.

Recollecting poor Pellucid’s warm admiration of the hexameter then, I have made strict search among his papers, on the chance of finding some classical Latin or Greek poem of his composition, but without success. At one time a ray of hope darted through me, as I came upon a paper carefully folded, and docketted, “Notions for a Fight between Hector and Achilles;” I unfolded it eagerly, but, alas! it was only a fragment, the words “Arma virumque cano” were legibly inscribed in my friend’s neat hand, but it was evident that he had either been called away, or that the Muse had deserted him at the critical moment, as he had left it without another word. At length I chanced to find the following poem, descriptive of a picnic at Cliefden and its consequences, in the true classical verse, but, before submitting it to the world, I must remark that on the outside cover of the MS. is written, in pencil, and in a hand very similar to that of Mr. B⸺, the publisher, of F⸺ Street, “Query? Evang’⸺;” the rest of the word is illegible, and I could never comprehend the meaning of the comment.

Note by the Editor.—In transcribing this poem from my friend’s MS., I feel it my duty to state that his touching description of his love was not without foundation. The “knock-down blow” he received did not entirely floor him; he sought to see the lady again, and, on being repulsed, commenced a very pretty little poem, beginning—

Here he stopped, which, I think, was a pity, as he evidently possessed the feeling and talents essential to an amatory poet.

PELLUCID RIVERS.—p. 105.

It is a melancholy pleasure to me to wander among these vestiges of the departed great man; to trace his various thoughts from his earliest infancy to the time when death robbed the world of what should have been its brightest ornament, and left to it merely the paste and tinsel, the gewgaw and tomfoolery of literature.

Of his father he has left many records. This person, upon whom the honour of being Pellucid’s progenitor devolved, appears to have been a worthy undertaker; an unprofitable one, however, for he never undertook anything well, nor carried it out successfully. Nevertheless, his failings or shortcomings in life, served but to increase the love his son bore him, and which is manifested in many poetical scraps, evidently written in early life, one of which, commencing—

is worthy of comparison with anything of Byron’s; it is, however, too long for extract. To his schooldays also, I find many pleasing allusions scattered through his manuscripts. In a letter to his sister (which, from family reasons, I am precluded from publishing) he draws a wonderful sketch of his pedagogue, whom he describes as being a man severe and stern to view, but who often relaxed to a joke with his scholars, and was the best hand at argument in the village, using words of such learned length and wondrous sound, that the amazed rustics stood gaping at his knowledge. His “Ode on a Distant Prospect of Islington Free-school,” is also full of pleasing reminiscences of his younger days.

Late in life Rivers began to take a great interest in theatrical matters, and I find among his MSS. the following poem, evidently written shortly before his decease. One curious fact connected[107] with these verses is, that as executor of poor Pellucid, I am at present at loggerheads with one Mr. McAuley, a Scotch gentleman, who, absurdly enough, claims their authorship:—

“Poeta nascitur non fit,” is a trite but wise aphorism. Few men have selected such varied subjects as my friend Rivers, and few have dealt with their choice so successfully. Unlike your modern writers, who put on one suit of similes and wear it threadbare (such as Alessandro Smiffini, for instance, who is never tired of gazing at the moon or dipping in the sea), Pellucid’s kindly nature immortalises even the most trivial occurrences of his life. The following extract from his works will show what I mean. Unblessed with riches, he had incurred a small bill at a restaurant, in the neighbourhood of his lodgings, and one night the proprietor of the hostelry effected an entrance into his apartment, and refused to quit until the claim was settled. This circumstance, which would have discomposed a less happy mind, gave him the idea for a set of verses, which he named “The Tankard,” and which he calls, “A Domestic Scene turned into Poetry.” Again, on this manuscript is a pencilled query (in the same writing to which I have before alluded), “Does he mean Edgar Poe—try?” I confess this joke is beyond my poor powers of brain. Perhaps my readers will be able to interpret it, when they read the verses, which run thus:—

I have concluded my extracts; the remaining poems are principally of a private and personal nature, which renders them unfitted for publication.

After a perusal of his verses there will, I trust, be very few persons who will not at once appreciate the powers of my lamented friend, and grieve over the illiberal treatment he experienced. Should I find that tardy justice is done to his productions, and that they meet with that posthumous popularity which is undoubtedly their due, the effort which I have made to bring him into notice, and to shake the dii majores of the literary world on their unstable thrones, will not have been unrewarded.

Edmund H. Yates.

LONDON:

SAVILL AND EDWARDS, PRINTERS, CHANDOS STREET

COVENT GARDEN.