The Project Gutenberg eBook of Little Mother Goose, by Anonymous

Title: Little Mother Goose

Author: Anonymous

Release Date: February 26, 2023 [eBook #70137]

Language: English

Produced by: Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

BOSTON

DeWOLFE, FISKE AND CO.

361 and 365 Washington Street

Copyright, 1895,

by

Alpha Publishing Company.

All rights reserved.

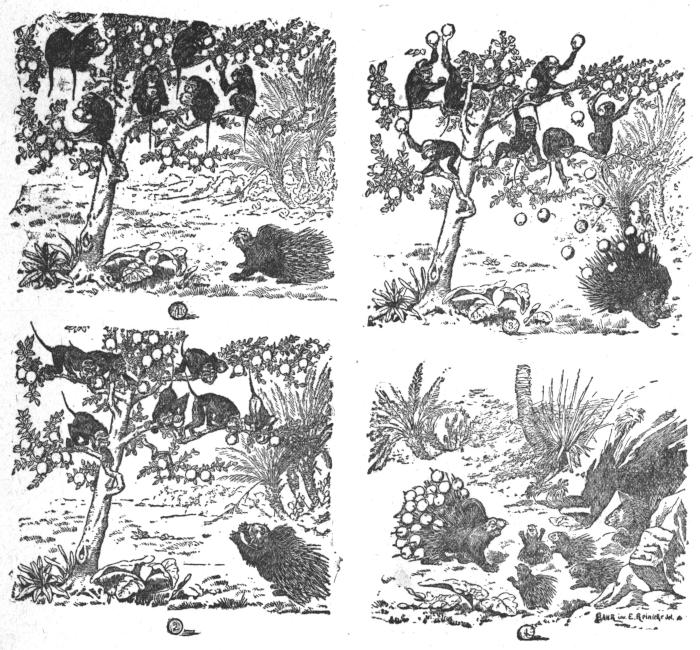

One day Father Porcupine was out hunting food. He came to a tree in which sat a lot of monkeys eating oranges. He asked for some, but the unkind monkeys only pelted him with the fruit as hard as they could! Then Father Porcupine laughed and put up his quills, and the oranges stuck on them. When his quills were stuck full he started for home, and he and his family had a fine dinner.

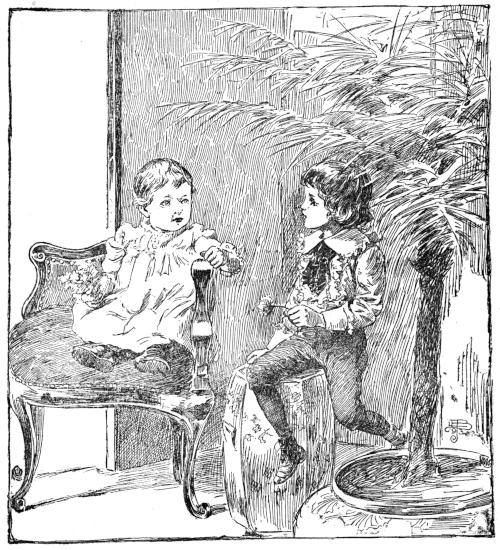

THE PLEASANT SPOT.

There was a “pleasant spot” in Mrs. Hall’s parlor, and every day at just three o’clock in the afternoon, if they had been perfectly good children, little Dick and Fanny Hall could go in and sit in that place an hour, and nobody else could go there at that time. The “pleasant spot” was under the green palm tree.

If they had behaved well, Dick and Fanny always went to their mother at ten minutes of three to be made as “sweet as roses.” But if they had been naughty they never went.

What did they do in the “pleasant spot?” They told each other stories, and they themselves made the stories.

Fanny’s stories were very short ones, such as this:

“One day a little small new small small baby-girl fly went into a rose, an’ her mama was not looking, an’ she los’ her way in the rose’s leaves an’ never comed out, an’ that little girl-fly never saw her mama any more, never, never, never again, Dicky.”

Dicky’s stories were short too, and such as this one:

“Sometimes, when little boys have a toy train, just a tin one, and they are playing with it, it turns into a live train, and the engine puffs out live smoke, and live people travel in it. But if their fathers and mothers look, or anybody, it is a tin train. And this is a fairy story, Fanny.”

Or like this one, which Dicky said was a “nadventure:”

“One time, when three little boys went up the mountain, they set their lunch basket down on the tip-top. In about two minutes they heard a noise at their basket, and a chipmunk stood there, and the chipmunk had one of their cookies in his paws!”

M. Dunleath.

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

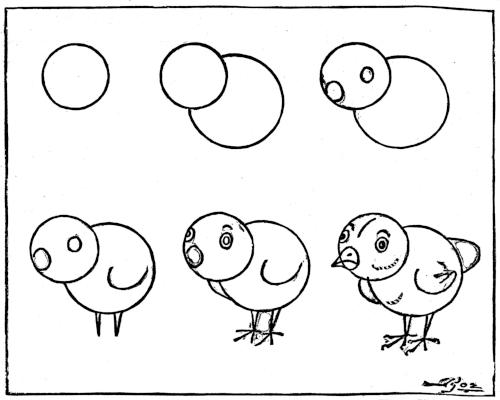

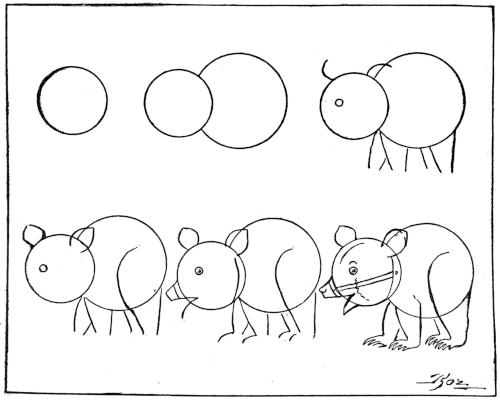

Draw a small circle around a small cent, a large circle around a large copper cent (or a two-cent piece, or a silver quarter), as in the designs—and then in a twinkling you will have a picture of a baby hen—that is, a chicken.

P. S. C.

Scene: A Nursery at night; a wakeful baby sitting up in its crib; the full moon shining in at the window.

BABY BEE AND THE MOON.

Pax Prescott.

“Why need I turn in my toes?” cried out Gosling Goose one day. “Little boys don’t, and I think it’s why they can run faster than we!”

Mrs. Goose smiled; but Mr. Goose said, “Goslings should be seen and not heard!”

“Mama, give me a keecoo,” said Carl.

“My child, there isn’t a cookie in the house,” said Mama.

“Do you wis’ you had some?” asked Carl, planting his chubby elbows in Mama’s lap.

“Indeed I do,” said Mama. “I certainly do wish that when Bridget went, she had left something in the house to eat!”

Five minutes later, Carl, with his mama’s large travelling bag on his arm, closed the back gate behind him, and trudged down the street.

A “lovely lady” that Carl knew lived in the first house round the corner, and he walked up to the front door and rang the bell.

The lady herself came to the door.

“Please give Carl keecoo. Bwidget’s gone, and us haven’t one fing in the house to eat,” and Carl extended the open bag to his astonished friend.

“Bless your heart!” she said, drawing her little friend in, and when he left he had ten cookies in his bag. She certainly was a “lovely lady” but Carl wished she hadn’t smiled so much with her eyes.

A little further on, another lady lived who often called to see mama, and Carl gave her door-bell a pull. This time a maid came, and Carl was shown into the parlor.

When Mrs. Lee came in and heard Carl’s errand she, too, “smiled,” and into his bag went eight beautiful doughnuts.

Three or four more friends were visited, and at every place Carl’s bag grew heavier.

With a happy heart he hurried home, and bursting into the sitting-room he excitedly empties the contents of his bag into mama’s lap.

There were cookies, yellow and brown, of all shapes and sizes, and doughnuts both round and square.

“Carl! Where in the world”—began mama.

“Yesh, isn’t you glad?” interposed Carl. “They was all gibbed to me for you, and every buddy sent their love!”

This is how “Keecoo Carl” came by his name.

Carrie A. Griffin.

P. S. C.

“Do you know any stories?” was the first thing Jimmy said to his little cousin visitor.

“I do,” said Sally, smiling. “What kind do you like best?”

“All the kinds,” said Jimmy promptly. “Do you know any about animals?”

JIMMY AND SALLY.

“I do,” said Sally. “I know a first-rate one about my own cat.”

“Tell it, now,” said Jimmy.

“I will,” said Sally. “I will begin it right now.”

Jimmy came around in front where he could “see every word.” “Begin!” said he.

“I am beginning,” said Sally. “My cat is just as old as I am. We were kittens together. Mama says she used to rock us in the cradle. One of the first things I remember, Jimmy, is my cat. She is a very big gray cat with a ringed coon tail.”

“Got a name?” asked Jimmy.

“She has. Big Betsey. Big Betsey goes to the country in summer. Mama wouldn’t think of leaving her behind to look out for herself. And we think, Jimmy, that Big Betsey always knows on what day we shall start. We think, Jimmy, that she understands a great many words that we say.

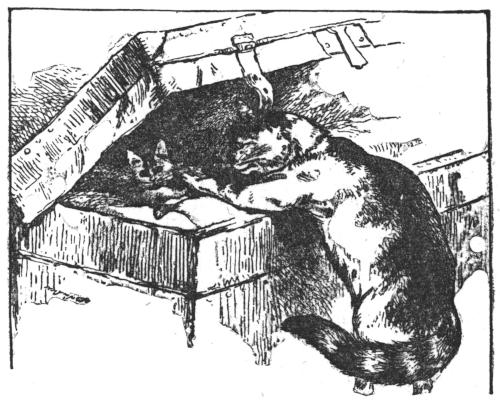

“Last summer she had a very smart handsome kitten, a great pet with us all, and we think Big Betsey understood us when we said we did not think the kitten could be taken too. The morning we were to start, when Mama went upstairs, there in one of the trunks lay Big Betsey’s kitten, and there Big Betsey stood packing her as nicely as possible, standing up on her back feet and tucking her in with her paws! Did you ever hear of such a thing, Jimmy?”

“No,” said Jimmy, “I didn’t. Did the kitten go?”

“She did,” said Sally.

“In the trunk? O, I hope she did—please, cousin Sally, please say she did!” entreated Jimmy.

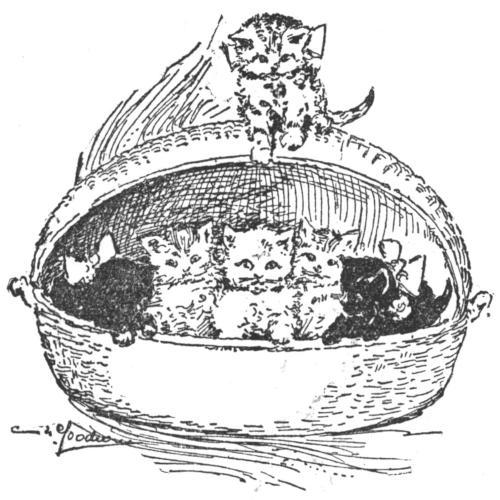

MY KITTY SHALL GO!

“She’d have smothered, Jimmy, all locked in where she couldn’t get any fresh air to breathe. She and Big Betsey went in a basket, and had part of my seat. This is The End, Jimmy.”

“It’s a very nice animal story,” said Jimmy.

M. Dunleath.

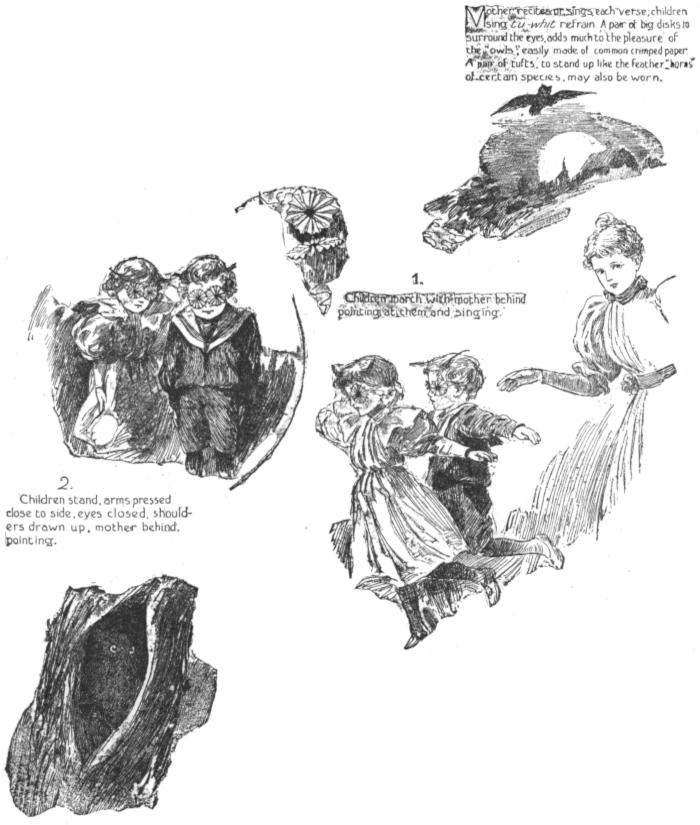

Mother recites or sings each verse; children sing tu-whit refrain. A pair of big disks to surround the eyes adds much to the pleasure of the “owls”, easily made of common crimped paper. A pair of tufts, to stand up like the feather “horns” of certain species, may also be worn.

1. Children march with mother behind pointing at them and singing.

2. Children stand, arms pressed close to side, eyes closed, shoulders drawn up, mother behind pointing.

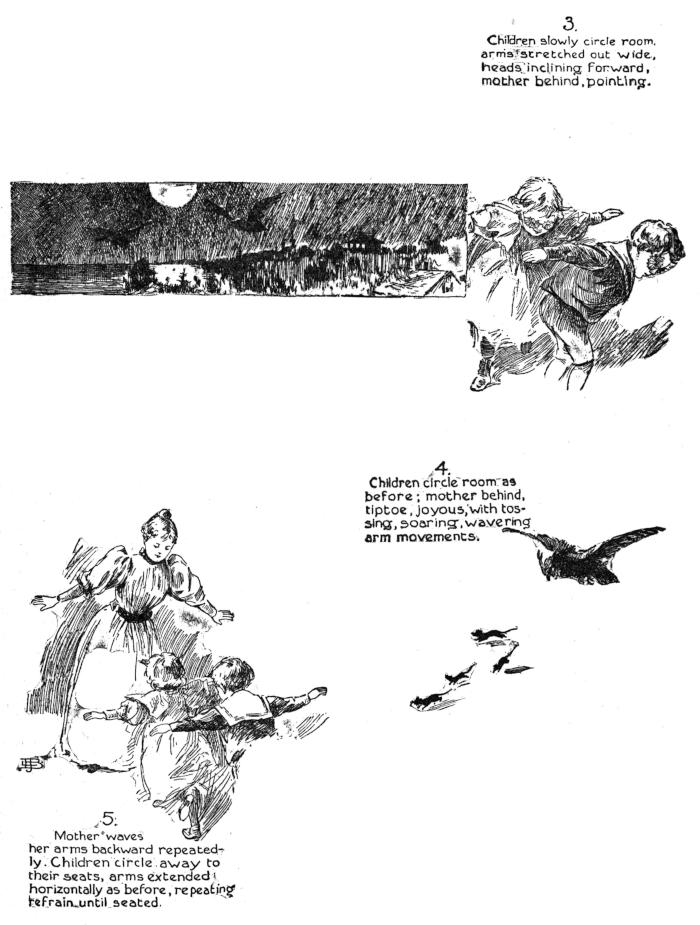

3. Children slowly circle room, arms stretched out wide, heads inclining forward, mother behind, pointing.

4. Children circle room as before; mother behind, tiptoe, joyous, with tossing, soaring, wavering arm movements.

5. Mother waves her arms backward repeatedly. Children circle, away to their seats, arms extended horizontally as before, repeating refrain until seated.

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

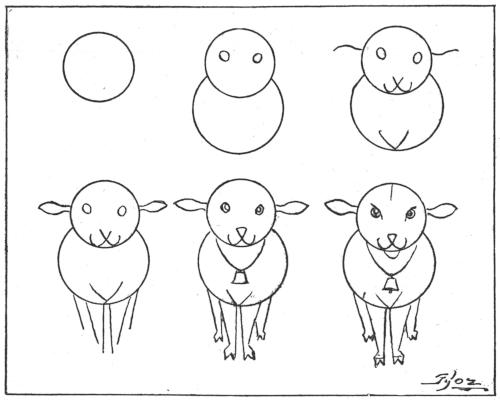

Draw two circles, a small one at the top, a large one below and behind it, as in the first two designs. Draw around a small cent and a large copper cent (or two-cent piece, or silver quarter). Add two tiny circles for eyes, then the lines in the following designs, and finally you will have a spring lamb with a tinkling bell.

(Lilybud to herself.)

(Lilybud to mama.)

P. S. C.

(Mother, or teacher sings:)

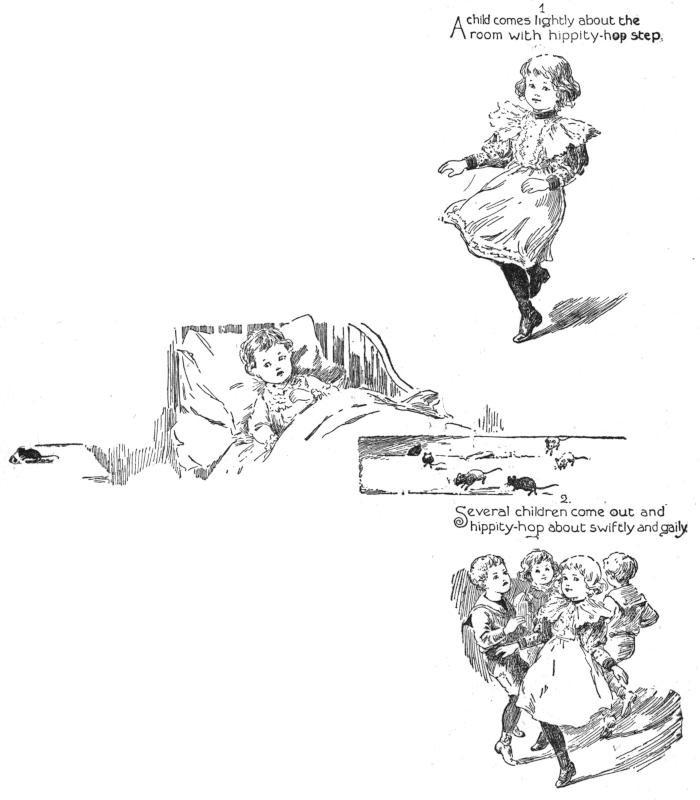

1. A child comes lightly about the room with hippity-hop step.

2. Several children come out and hippity-hop about swiftly and gaily.

(Child sings:)

(Mother sings:)

(Children, pausing, sing:)

(Mother sings:)

(Children sing, joining hands, dancing in a round:)

3. Children hippity-hop around in pairs, joyously.

4. Children hippity-hop about gently.

(Mother sings:)

(Children sing, dancing in a round:)

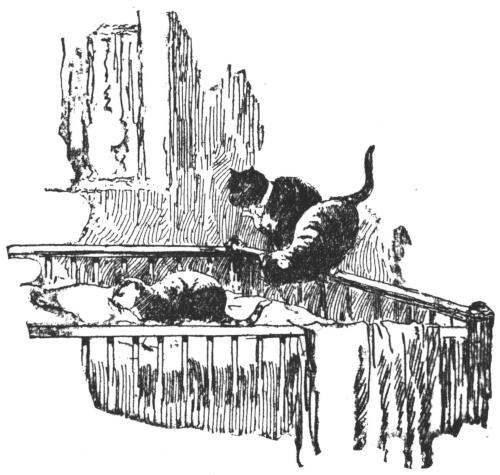

Miss Howells has told the story of Posy Pinkham’s cat that dreamed. This is a story of two other cats Posy had.

The cats were sisters. Their names were Fluff and White-face. Fluff was a gentle milk cat. White-face was a fierce mouser. White-face would often bite and claw her sister, but Fluff never bit and clawed back.

Once, however, Fluff bit and clawed first, and there was a fight, and Fluff—but that’s the story.

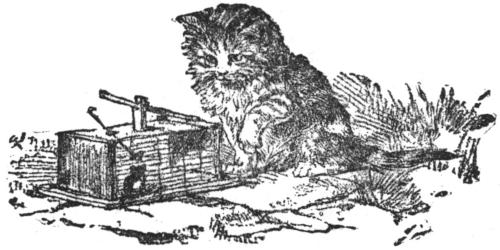

Papa Pinkham had caught a gray mouse in the wire cage-trap. It was so cunning Posy begged to keep it, and Papa Pinkham left it in the cage-trap and went off to business. Posy fed the mouse with five kernels of corn, and then went to dress her doll Lilybell for breakfast.

FLUFF ALSO ADMIRES THE MOUSE.

Fluff had been looking on. Now she went close up to the cage and sat down.

Just then White-face came creeping, creeping up, in the way of mouse-hunting cats.

“Hush,” she whispered to Floss; “there’s a mouse; see me catch it!”

THE FIGHT.

“No,” whispered Floss, “it’s such a cunning mouse, so soft and smooth, such bright little eyes, such a long slim tail—no, don’t.”

“I shall, I say!”

“No, you mustn’t—besides, it is Posy’s mouse.”

“I don’t care, I want it!”

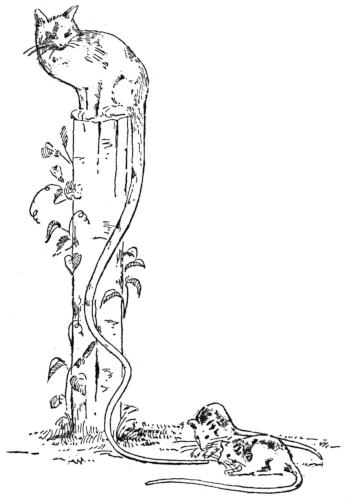

UP THE TREE.

Just then the mouse moved so its tail came through the wires. White-face sprang, but Floss sprang quicker, not at the tail, but at her fierce sister.

White-face was very angry; she bit and clawed terribly; she scratched Floss across the face—but Floss fought on.

At last White-face got away, and ran out the door and up a tree. Floss chased her and nipped the tip of her tail as she climbed. Then she ran back to the house, and told Posy all about it.

WEARING THE RIBBON.

Posy hugged the kind little cat, and tied a beautiful ribbon about her neck, and told her she was brave as a lion, and kind as—as—a little girl!

But White-face got no ribbon, and no praise—and she was so scared she staid up in the tree all day.

C. P. Stuart.

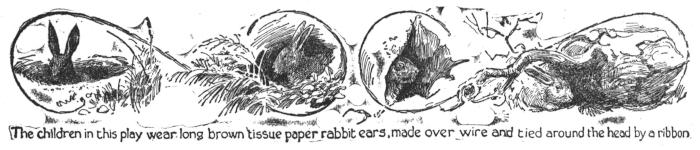

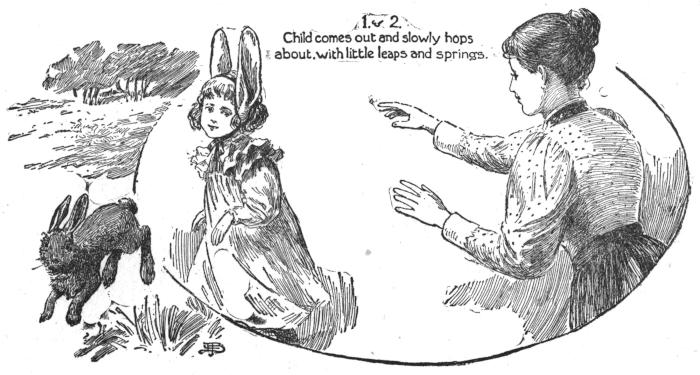

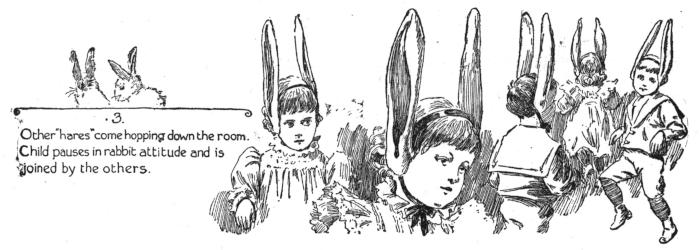

The children in this play wear long brown tissue paper rabbit ears, made over wire and tied around the head by a ribbon.

(Mother sings:)

(Child sings:)

(Mother sings, seeking to capture child:)

(Child sings, springing away in little leaps:)

1. & 2. Child comes out and slowly hops about, with little leaps and springs.

3. Other “hares” come hopping down the room. Child pauses in rabbit attitude and is joined by the others.

(Mother sings, following after child:)

(Child sings:)

(Mother sings:)

(Children sing:)

(Mother sings, shuddering:)

(Children sing, springing away:)

4. Children circle room to seats.

THE GREAT SAND FORT.

Ella Farman Pratt.

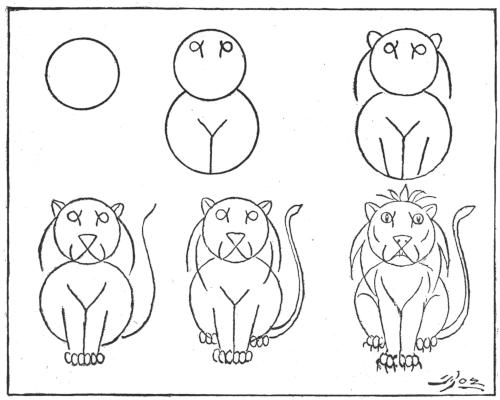

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

Draw a small circle (around a small cent), then a large circle directly below and behind it (around a large copper cent, or two-cent piece, or silver quarter), as in the first and second designs. Then add the lines in the following designs, and a big lion will sit staring at you.

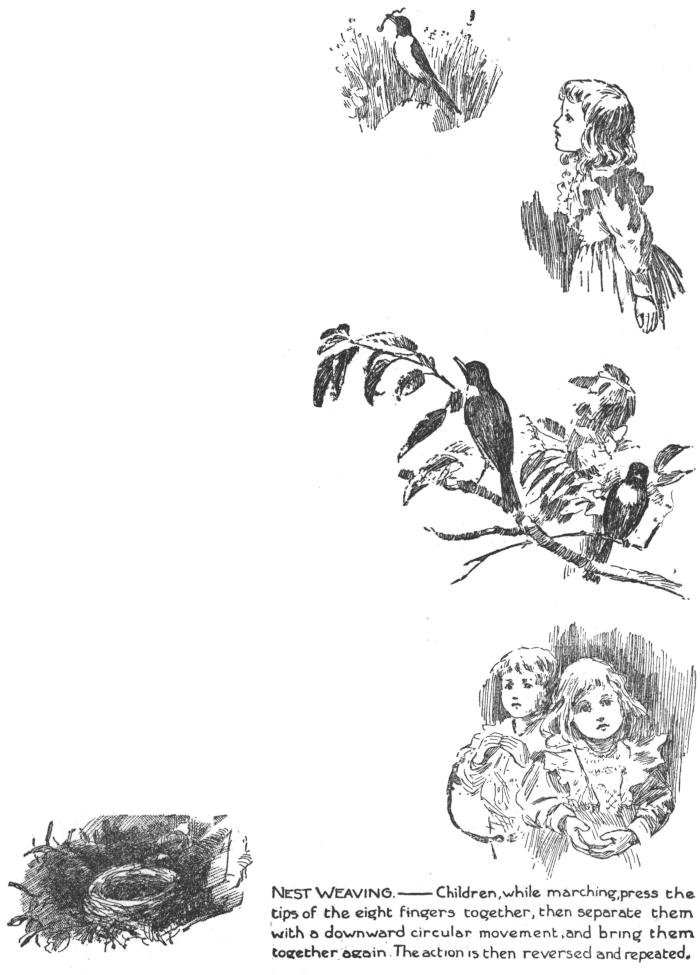

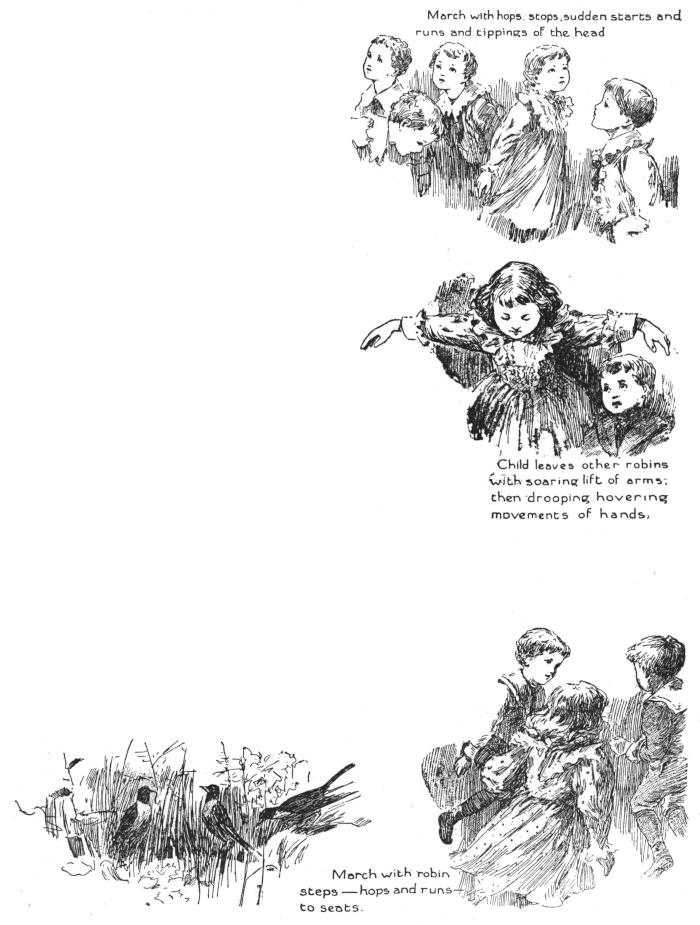

(A child is heard singing “Chee-ree! Cheer-up.” Looking about, this way and that, mother sings.)

(Child enters, singing.)

(Mother sings.)

(Children enter, singing robin refrain.)

(Mother sings.)

(Children sing robin refrain.)

Nest Weaving.—Children, while marching, press the tips of the eight fingers together, then separate them with a downward circular movement, and bring them together again. The action is then reversed and repeated.

March with hops, stops, sudden starts and runs and tippings of the head.

Child leaves other robins with soaring lift of arms; then drooping hovering movements of hands.

March with robin steps—hops and runs—to seats.

(Mother sings.)

(Children sing robin refrain.)

(Mother sings.)

(Children sing robin refrain.)

(Mother sings.)

(Children sing robin refrain.)

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

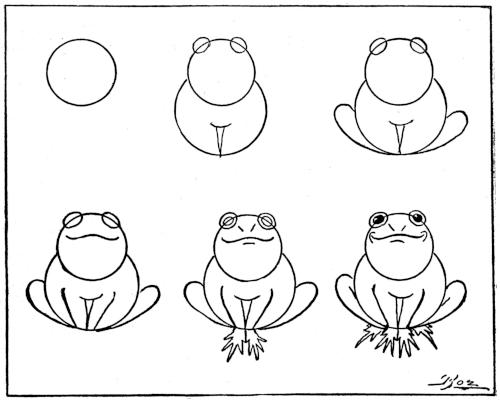

Draw a small circle (around a small cent), and a large circle below and behind it (around a large copper cent, or two-cent piece, or silver quarter), as in the first two designs. Add eyes, mouth, legs and feet, as in the other designs, and a fat frog will smile up at you.

M. Dunleath.

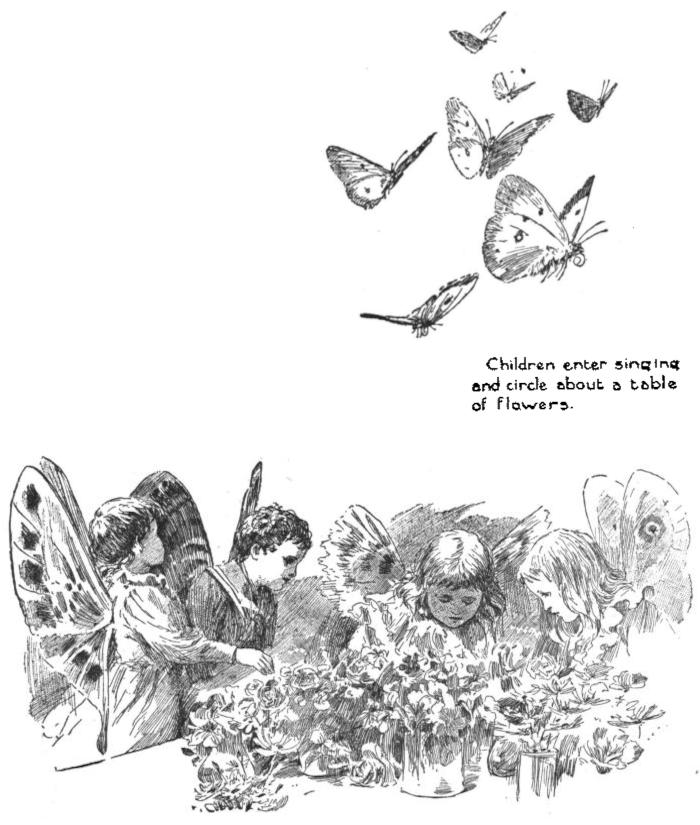

A few slight changes, such as “I am a butterfly” for first line, will fit the song to be sung by one child instead of several. The suitable changes will suggest themselves to mother or teacher. A butterfly-look may be given to the little ones by wings of tissue paper fastened between the shoulders, or even by broad bows of wide, gay-colored ribbon.

Children enter singing and circle about a table of flowers.

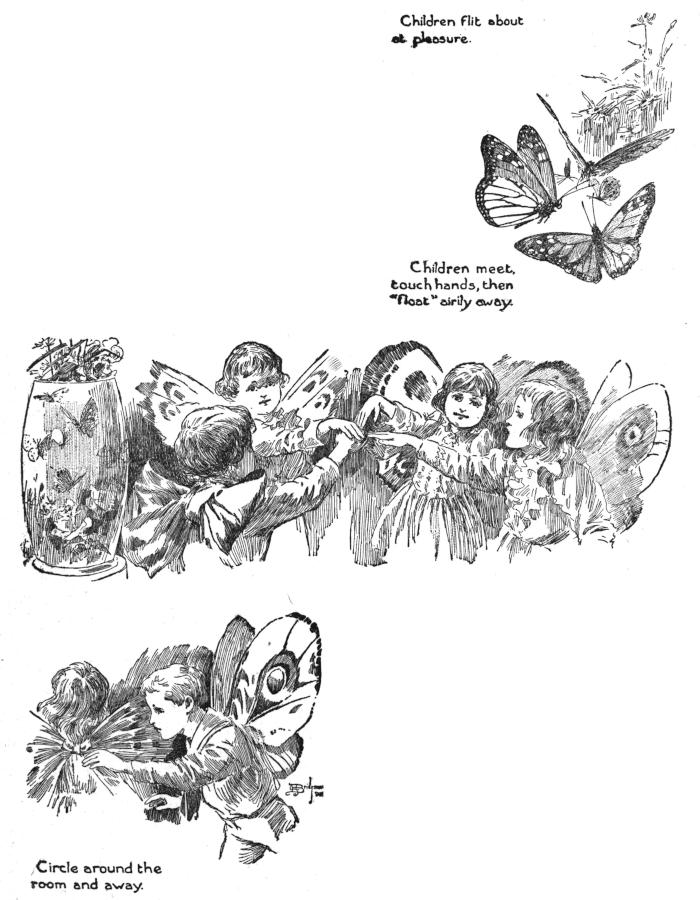

Children flit about at pleasure.

Children meet, touch hands, then “float” airily away.

Circle around the room and away.

Little Janie came up to her big brother. She laid her little thin hand on his book. “Charlie, I wish I had something nice and new to play with,” she said to him.

“All right,” said Charlie, laying down his book. “You shall have it. What shall it be?”

Little Janie had been very ill a long time, and now everybody was very kind to her, very patient. Poor little Janie!

“Well,” said Janie, “I wish I had a pony to ride.”

“All right,” said the big brother, “you shall have him, in just twenty minutes. I will come in just twenty minutes and get you.” And off he went.

In about twenty-two minutes he was back again. First he blindfolded Janie. Then he took her in his arms and carried her away. Then he set her down on—a pony. Then he took off the “blindfold.” And then little Janie laughed. It was indeed a very, very funny pony on which little Janie sat.

Laura Howells.

THE PONY CHARLIE MADE.

MY KITTEN.

Eleanor W. F. Bates.

THE OLD WHITE MANSION.

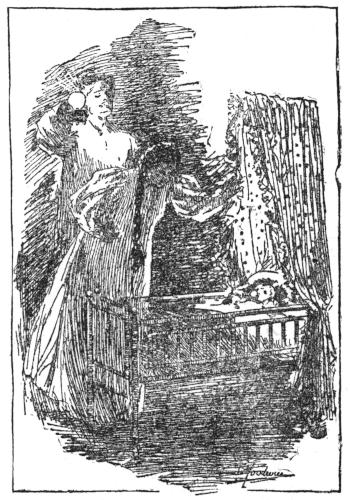

There was a day in her baby-life that little Mary Ellen always spoke of as “my first day.”

“It was when I was a little crib-baby, a little bye-o-baby, you know,” Mary Ellen would say.

Mary Ellen meant it was the first day she could remember.

She remembered it by two things—it was the first time she ever heard her pretty mama scream, and the first time she ever got her little hands into the fur of a cat.

Mary Ellen was in her crib, in the pretty baby-room of the big white mansion, called “The House of the Grandmothers.” A pink rosebush was growing in a blue-and-white pot, a yellow canary hung in the window, and the sunshine was streaming in over everything. Mary Ellen was lying awake, looking at the pretty window, when all at once something made her turn her eyes.

There, on the foot-rail, sat some beautiful, furry, bright-eyed creatures, looking at her, and making the most lovely noise. She smiled at them, saying, “goo-goo-goo.” At that, one of them hopped down on the quilt, then came closer, blinking its green eyes and still making the lovely noise. Mary Ellen’s tiny body gave a quick little spring, and—O, delightful!—her hands grabbed into the soft warm fur of a kitty.

Then came the scream, and mama with it, both through the open door.

“Dick! mercy! come quick! scat! scat!”

Not only papa came, but the two grandmamas and one of the great-grandmothers, all four looking scared.

“They were right on the foot-rail of her crib—the three tiger-cats,” gasped mama, “and one had jumped down on her! I don’t much think they’ve scratched her, but they might have—just think of it, Dick!”

Papa Dick smiled. “Awful!” said he. “No doubt, Nan, they came in purposely to eat your baby up!”

The grandmothers smiled too. “Nan! as if our cats would hurt Mary Ellen!” said the youngest grandmother.

“Well, you can all laugh,” said Mama Nan, “but I think six cats are much too many in a house where there’s a baby.”

THE TIGER CATS.

“Six cats is rather many,” laughed papa, “but then there are six grandmothers, too, you know, to keep them off.”

Ella Farman Pratt.

There were two or three other events in her baby days that little Mary Ellen always wished she could remember.

THE BIG CAT-BASKET.

One was her first birthday celebration. It was not like any that any other little baby ever had. Little Mary Ellen had a birthday when she was six months old!

The youngest of the four great-grandmothers, Mrs. Persis, was talking one day with Madam Esther, the next-to-the-oldest great-grandmother. “It is time Nan’s baby had some kind of a celebration,” said she. “Why not let her have a birthday the day she is six months old?”

“Who ever heard of such a thing!” Madam Esther gasped.

“Why, we have!” laughed Grandmother Lee, Mary Ellen’s father’s mother. “All we six here have heard of it, hav’n’t we, just this very minute?”

“Well, this is an idea,” said Grandmother Camp, Mary Ellen’s mother’s mother. “A birthday at six months old! Still, if we choose, what is to prevent? I’ll ring for Nan.”

They were all in Miss Persis’ room, the large southwest corner room, in their rocking-chairs, sitting in the sun. The cats lay in the big cat-basket, basking in the golden warmth.

When Mama Nan came in, her mother told her the plan. “Did I ever hear anything so absurd!” cried Mama Nan.

Papa Dick said, “Why not?” and helped the plan on.

So Mary Ellen had the celebration. It was held in Mrs. Persis’ sunny sitting-room, and she was taken in in her best embroidered robe and blue ribbons with a pink rose stuck in each bow, and the cats had new blue ribbons with rosebuds tied in—and what do you think was the center-piece on the tea-table?

Why, Mary Ellen herself, on a pink sofa pillow, nestled in among the big lace ruffles!

And her birthday presents? Six white sugar-candy doves. And when, one by one, they were held up to her face to see, what do you think Mary Ellen did? At the last dove she put out her little pink tongue on its white breast and had her first taste of candy.

MARY ELLEN AND THE CANDY DOVE.

It was a beautiful time, and too bad it was little Mary Ellen couldn’t ever remember it!

Ella Farman Pratt.

Two other celebrations followed little Mary Ellen’s birthday as fast as possible. Mary Ellen’s mama said the baby’s six grandmothers made her dizzy with their frolicsome plans.

THE SIX STOCKINGS.

But Christmas was coming, and certainly a baby’s first Christmas must be celebrated.

Great-grandmother Day, one of Mary Ellen’s father’s grandmothers, said one day to Mama Nan, “I suppose Mary Ellen has six stockings?”

“Why, yes, I suppose so—why do you ask?”

“You may hang them for her Christmas Eve,” said the venerable lady. “Stockings have never been hung in this house, but Mary Ellen probably will have to be indulged.”

Great-grandmother Day was the oldest of the four great-grandmothers. She was a very dignified old lady, and wore steel-bowed spectacles and carried a snuff-box in her pocket with a vanilla bean in it, and was treated with the greatest respect throughout the house.

Christmas Eve, six baby socks hung in a row in the nursery, and what do you think was in them next morning?

Six tiny packages, just alike. There were six fifty-dollar bank notes. Each was labelled: “To be kept for Mary Ellen’s wedding-dress.”

Mary Ellen’s mama looked as if she would cry. Papa Dick said, “I wonder what these grandmothers will do next!”

Mary Ellen’s next celebration was on New-Year’s Day. Nothing would do but that the Baby must make New-Year’s calls. Her mama feared she might take cold from “drafts,” being carried in and out of so many rooms, but Papa Dick said, “O, bundle her up!”

So New-Year’s morning Mary Ellen was dressed in her long white cashmere cape-cloak and her white velvet hood, and was carried about the house, up stairs and down, to call on her grandmothers in their own rooms. She was quite equal to the occasion. She said, “Da-da, da-da!” (“Happy New-Year!”) to each and every one who took her mite of a hand, and came home to her crib with something shut fast in her fingers her mama did not see at all!

Ella Farman Pratt.

MAKING NEW-YEAR’S CALLS.

What it was Mary Ellen had in her soft little pink hand when she came back from the New-Year’s calls and still had in it when she was laid in her “cribsie-nest” New-Year’s night, nobody knew.

“DON’T YOU SMELL PEPPERMINT?”

It was small and round and flat and smooth. Mary Ellen hardly felt it, and as the hand of a little baby mostly keeps itself shut very tight it did not drop out, and by and by it grew just the least bit sticky and staid fast.

To be sure, when Mama Nan was undressing her and putting on her nightgown she suddenly began to sniff. “I seem to smell peppermint,” she said, and dipped her nose down among Mary Ellen’s ruffles. Then she lifted her head and sniffed all about in the air in the funniest way. “If she were not mine,” she said, “I should certainly say somebody had been giving this child peppermint! Come here, Dick! Don’t you smell peppermint? Put your head down here!”

Papa Dick put his nose down in Mary Ellen’s ruffles and sniffed. He said it did seem as if he got a whiff of peppermint, but perhaps babies always smelt of peppermint.

“Of course she hasn’t had any,” Mama Nan said at last, and they went out and left the baby to her dreams, and the baby said nothing. The little hand staid shut, and she went to sleep.

HE FLASHED UP THE NIGHT LAMP.

That night, suddenly, just as the nursery clock began striking twelve, there was an outcry from the crib, so sharp, so painful, that it brought Mama Nan to her feet in the millionth part of a second. Papa Dick, too! He flashed up the night lamp and then there was a second scream, from Mama Nan, and she dropped in a heap by the crib. As for Papa Dick, his hair stood on end. He dashed at the crib and snatched a small mouse, a live mouse but ever so little, from Mary Ellen’s fingers that were clutching it tight. In his horror he flung it into the water-pitcher. Then he flung the water, some of it, and the mouse with it, into Mama Nan’s face, for she had fainted; and the mouse leaped from Mama Nan’s wet cheek and ran for his life.

The next minute both were bending over Mary Ellen. Her big blue eyes, full of tears, were just shutting to sleep again. A tiny pink peppermint lay on the crib quilt. Mama Nan pounced on it. “What did I tell you!” she cried.

Papa Dick was examining the warm little hand. It was very sticky and sugary. There was a tiny red spot, like a pin-prick, on one side of the palm. “The mouse was after the candy,” said he, “and she just shut her fingers on him when he bit—hurrah for our baby, Nan!”

“Bit!” screamed Nan, and for a moment she looked as if she might faint again. “Old Lady Lois must have given it to her when we were upstairs to-day—she is forever eating peppermints! I should think she would have known better!”

But dear Old Lady Lois, who truly was as fond of sweets as a child, had not given her the peppermint. She had dropped it on her lap and little Mary Ellen’s hand had chanced to close over it, and had brought it home.

Ella Farman Pratt.

The Grandmothers were in Mrs. Persis’ room. Large and sunny, it was the favorite sitting-room, and the big cat-basket was generally kept there.

As usual they were all doing something for Mary Ellen. Grandmama Camp was embroidering on a little petticoat. The others were embroidering too, or crocheting, except the oldest two of the great-grandmothers. Mrs. Day was knitting a yarn stocking about the size for a little girl of six, Old Lady Lois was pasting colored pictures in a scrap-book.

They were talking of the child. “I often wonder how she is ever going to know us apart,” Grandmama Lee was saying. “Six of us!”

Mrs. Persis laughed. “Poor baby! who ever before heard of six grandmothers in one house! just how she will learn to tell us apart is a question!”

“MRS. PERSIS.”

“I never thought we resembled one another,” remarked Great-grandmother Day.

No, they did not.

MRS. CAMP AND OLD LADY LOIS.

There was Grandmama Lee, and Great-grandmother Lee who was called “Mrs. Persis,” and Great-grandmother Day. These three belonged to Papa Dick and had lived in the house ever since he could remember. Grandmama Lee, Papa Dick’s mother, was young and plump and smiling, with nut-brown hair waving over her forehead—a very nice grandmother. Great-grandmother Lee, “Mrs. Persis,” was roly-poly with a double chin, puffs of white hair, bright eyes, and any of the cats sat on her shoulder when they liked. Great-grandmother Day was the one who walked with a cane and wore caps.

Grandmama Camp and Great-grandmother Camp and Great-grandmother Gray who was called “Old Lady Lois,” belonged to Mama Nan, and when Papa Dick married her he brought them all home to his own house. He said he liked the idea. Mrs. Camp, Mama Nan’s mother, was a young, handsome, stylish woman with black hair and black eyes. Great-grandmother Camp, called “Madam Esther,” was tall and also had black hair and black eyes. “Old Lady Lois,” Mrs. Gray, was quite a beautiful old lady. She had a sweet face, and always wore a flower in her soft white mull kerchiefs.

“I think I know,” said Grandmama Camp, looking around on the others, “just how Nan’s baby will tell us apart.”

“How,” they asked. But she would not tell them.

Ella Farman Pratt.

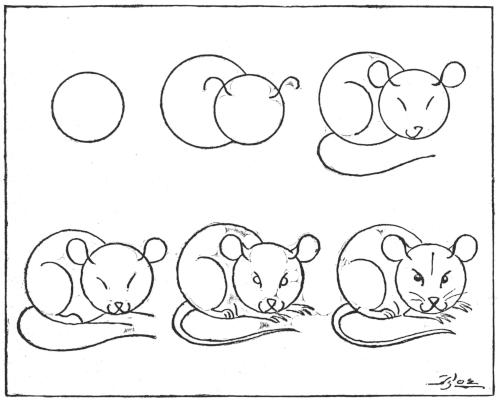

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

Draw two circles, one small, one large, the small one lapping over the other, as in the first and second drawings. Use a small cent in drawing the small circle, and a large copper cent (or a two-cent piece, or a silver quarter) in drawing the large circle. After that you will easily make a picture of a bright-eyed, long-tailed, nibbling mouse.

One day, suddenly Mary Ellen began to creep.

“CREEP! CREEP!”

She was sitting on the rug, reaching for her playthings—her rag doll and her rag kitten. She had tossed them too far and there was no one in the nursery to help get them, and finally in her repeated reaching forward, over she went on her nose! Mama was not there to set her up again and say, “Bumpity-bump! Up she must jump!” and she whimpered a bit. But she wanted her playthings, and struggling for them she kicked her little legs out behind her and tried to jump along on her little stomach. At last in her mighty effort she drew her little knees up under her, lifted her little back, and away she went, creep! creep! creep! and with a very red face and a gurgle of delight grabbed her doll and cat. Then she tumbled down on her face again. But finally she got herself turned over, and lay there on the carpet, contented.

And there she still lay, gurgling and cooing over dolly, when Mama Nan came in, and Grandma Camp. Mama Nan stared at her baby, then at the rug where the ivory rattle and pillows lay, then at Mary Ellen again.

“What does this mean?” she cried. “She is fully ten feet away from where I left her!”

Mama Nan’s mother smiled. “I think, Nan, that Mary Ellen has had another adventure. I rather think she has been creeping!”

For a moment Mama Nan looked more astonished and bewildered than before. Then she turned and flew out along the little hall that led to the library. “O, Dick!” she cried. “Come in here! What do you think? Mary Ellen has been creeping.”

Papa Dick looked, for a second, fully as astonished as Mama Nan. Then he said, “Well, it’s all right, isn’t it? She’d have to do it sometime, wouldn’t she?”

MAMA NAN IS ASTONISHED.

Mama Nan breathlessly told him about it. “Well,” he agreed, “it must have been quite an exhibition. Suppose we go in and see if she can be got to repeat the performance,” and back to the nursery they both hurried.

Ella Farman Pratt.

But there was something more to be done than just to say, “Come, Baby! come to mama,” to get Mary Ellen to creep again.

“COME GET THE BOO’FUL BIRD!”

Mary Ellen’s papa, mama, and maternal grandmama all got down on the floor at the opposite end of the room, and smiled and held out hands and coaxed and chirruped; and Mary Ellen smiled in return and crowed and jounced her little self up and down, and seemed ever so many times to be on the very point of starting to go, but after all did not once make any effort to get over on her little hands and knees and creep. It ended every time in her sitting there and reaching for them to come over and get her.

“She’ll never do it again,” said Mama Nan.

“Perhaps she hasn’t at all,” said Papa Dick. “She may just have rolled there. Do you know that she crept?”

“Oh! she crept,” said Mrs. Camp. “I examined her hands and knees.”

Now there was one thing Mary Ellen had always wanted more than anything else and many times had reached up her little hands for—the red and green parrot on the bronze perch. But though the bird had an equal curiosity about the baby, Mama Nan would never let Dom Pedro be brought near her child for fear that cruel hooked bill might bite!

But now, suddenly, she said, “See here, Dick! go get the parrot!”

When the bird was brought and began to shout, “Holloa, Young Woman!” which was Papa Dick’s usual salutation to his daughter, Mary Ellen began to jump herself up and down again and pat-a-cake in a perfect frenzy of delight.

“Come get the boo’ful bird!” called Mama Nan. “Come to mama, baby, and have the pretty bird!”

But Mary Ellen seemed to have lost all knowledge of her new art of locomotion. She continued to jounce and crow, while her papa had to grasp hard hold of the parrot to keep him from flying out of his hands.

MARY ELLEN AND DOM PEDRO.

In the midst of the excitement Old Lady Lois came in. The reason of the queer scene was explained to her. “Bless your hearts!” exclaimed she. She crossed the floor, lifted the child, poised her a moment on her feet, then gently laid her down, face forward; and at that second the parrot flapping his wings in a new struggle to fly, Mary Ellen, with a great crow set off on hands and knees to meet him.

Quite around the nursery she followed after her papa and the brilliant bird. Then, as reward, she was taken up on her papa’s knee, and let to lay her little hand upon the feathery green back and to stroke the gorgeous green and red tail feathers. As for the parrot—of course he did not bite! he only said, “And what d’ye think now, Young Woman?”

After this, Mary Ellen could creep; could creep with the greatest velocity. But whenever she crept, and wherever, her journeys always ended at the foot of the bronze parrot-perch, and Dom Pedro always leaned over and spoke to her, and said as he peered down at the golden-haired little girlie, “Holloa, Young Woman! holloa!”

Ella Farman Pratt.

MARY ELLEN’S FIRST TOOTH.

Almost as soon as Mary Ellen could creep, she tried to walk; and on the same day she took her first step “all alone-y,” a little tooth came into sight. The big white house was in a state of excitement. The grandmothers were downstairs all day. Mrs. Persis was sure she had felt the tooth for a week. All had to touch the bit of sharp pearl. “I believe the little rogue knows she is biting us,” Madam Esther said as Mary Ellen let go her finger with a gurgle of a laugh. She pointed out a tiny red spot on her finger and declared the tooth had made it. The others came and gazed, and Papa Dick said grandmothers were queer beings.

But he and Mama Nan “felt” the tooth, too, when once they were alone with Mary Ellen. They seemed to think it very wonderful that the tiny pearl should appear in their baby’s mouth. They peered at it so often during the next few days that at last, if anyone said, “Now let’s see ’ittle toofy!” Mary Ellen began to cry and scream.

After Mary Ellen could creep she wouldn’t stay on her rug. She would hitch along until off, and then start to creep. Next minute up she would raise her little body and walk off, all-fours, on hands and feet, pounding along like a little dog until she got to a chair, when she would pull herself upright. Then, with her little hands patting the chair-seat joyfully, she would step about it as fast as she could go, jumping, gurgling and crowing, until in her wild glee down she would tumble! And one day, in climbing up after a tumble, she found the chair could walk too! Mary Ellen made experiments. A good smart push, and off the chair would start over the smooth floor, and Mary Ellen with it, crowing like a little rooster.

AT THE OPEN DOOR.

Suddenly, one morning Mary Ellen appeared to have an idea in her little head. She had been left on the rug with her playthings. There was no one in the room except the cats and Dom Pedro. The cats raced about, and Dom Pedro scolded: “Scat! Scat! Less noise I say!” Mary Ellen took no notice. She set off, hitching along, for the door open into the hall. As soon as she was over the threshold she started on a fast creep for the stairs.

“Young Woman!” Dom Pedro called. Mary Ellen crept on, the cats frolicking along with her. Dom Pedro’s perch stood where he had a good view of the stairs, and now, as Mary Ellen laid her little hand on the bottom step he burst into a perfect frenzy of hoarse calls and squeaks.

Ella Farman Pratt.

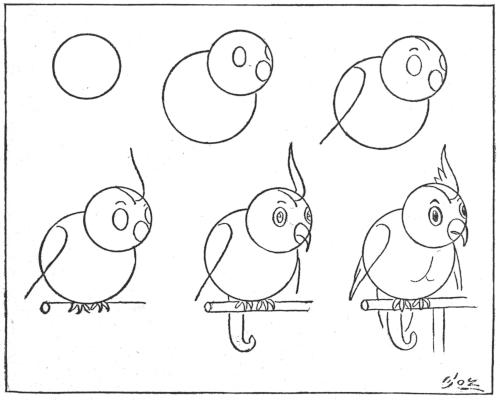

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

Draw a small circle, and then a large circle below and behind it, and a little to one side—as in the first two designs. (Draw the circles around a small cent and a large copper cent, or two-cent piece, or silver quarter.) Add the lines in the other four designs, and you will have a pretty Poll Parrot on its perch.

SHE CAME TO A DOOR.

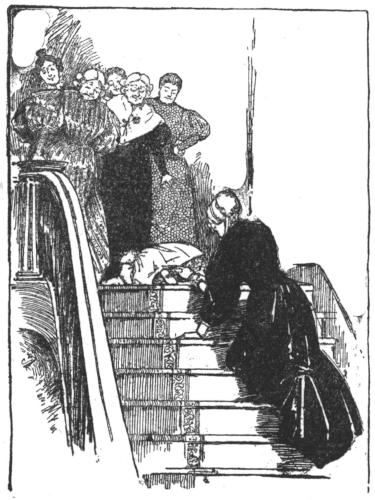

Mary Ellen paid no attention to Dom Pedro’s cries. She pressed one fat hand down hard on the first stair and steadied herself and straightened herself up until her little knees were level with the step, and then on it—and there she was, up a stair! Her little face was very red, and she was very puffy all over. But she seemed to have an instinct as to what to do next. Or perhaps she had studied it all out on her rug. Learned men are trying to pry into the minds of babies now, but as yet none has discovered very much as to what a baby thinks of, or whether it thinks anything. She grasped hold of a baluster-round with one hand and laid a sturdy little knee on the next stair, and in this way up she went, panting and puffing and getting on up, she and the kittens, but never making a loud sound, excepting a little grunt now and again.

But the moment she reached the top she broke out into a delighted gurgle of little words: “Gum-um! gum-um!” Then she got herself on her feet—a very dusty, mussed-up, red-faced, white-frocked baby, her sunshiny hair wet on her heated forehead, but her blue eyes sparkling. She steadied herself in her little red kid slippers and then, her hands against the wall, she stepped along, step by step, until she came to a door. On that she spatted with her two little hands and said, “Gum-um! gum-um!”

There was a sudden hurry inside, and the door opened, and Mary Ellen and the six kittens went tumbling in together down on the floor. Great-Grandmother Day cried out, “The Good Lord preserve us!” and sank back in a chair.

The next minute she had caught the child up. Mary Ellen was crying lustily, for she had bumped her nose in a very bad way, and as Great-Grandmother Day sank back with her in the chair again, doors flew open all about and grandmothers came flying along from all quarters.

MAMA NAN LOOKED WHITE.

“What is it? Is Mary Ellen here? What is the matter?”

Great-Grandmother Day addressed herself to Madam Esther. “I know you keep brown paper by you—bring me a piece of brown paper wet in ice water for this child’s nose.”

At this moment, brought by Mary Ellen’s shrill screams and the parrot’s outcry, Mama Nan appeared flying up the stairs.

“What is it? Where is Mary Ellen? Have you got Mary Ellen up here?”

She entered just as the piece of brown paper was being laid on Mary Ellen’s nose, and her words ended in a little shrill cry like that of a frightened mother-bird.

“This child came up the stairs alone!” said Great-Grandmother Day, severely, speaking to all in the room. She rose and delivered the child to its mother and then, faint for the first time in her life, was led back to the chair by Old Lady Lois and Mrs. Lee.

By this time Mary Ellen was snuggling down in her mother’s neck in great content, and her sobs were ceasing. But poor Mama Nan looked very white. “I shall never know another moments peace,” she said piteously.

“Nonsense,” said her mother. “You did the very same thing yourself, Nan. You were just about the age of Mary Ellen.”

On the way downstairs, Mary Ellen raised her head and said, “Gum-um! gum-um!”

“Yes, you did go to see Gum-um,” answered her mama; “but you mustn’t do it again.”

Ella Farman Pratt.

None of the “gum-ums” supposed Mary Ellen would try coming up stairs again. Her poor little bumped nose would be a warning. But Papa Dick thought she would, and said someone ought to be in the nursery all the time.

“MARY ELLEN MUSTN’T TOUCH!”

“No, no,” said Mama Nan. “My little Mary Ellen must grow up able to do right without being watched. If somebody sits by her and prevents her from everything, how can I ever tell whether she is good or whether she is bad?”

“Well,” said Papa Dick, “I hope you wont come to grief a-carrying out your ideas about your little Mary Ellen.”

The next day after her adventure, Mary Ellen was left alone as usual with her playthings. Her little nose was black-and-blue, and gave her a look of not being a specially good child. Once or twice she put her little hand up to her face. “Nosey ache, Dom P’e-do,” she said to the parrot.

Great-Grandmother Day’s tall old pier glass stood in the room. On its low marble shelf Mama Nan generally kept a vase filled with flowers. It was a glass vase, and very tall and slender. She had been warned about leaving this vase in Mary Ellen’s reach. “She will pull it over some day,” said Madam Esther, “and the vase’ll break and she’ll get cut with the broken glass.”

Mama Nan said “no, she is to learn not to touch things.” But after the parrot, the vase of flowers was the first object the baby took notice of. Mama Nan would take a flower out and give to her, then set the vase back, shake her head and say slowly, “Mary Ellen mustn’t touch!”

“Mary Ellen is a little human being,” she said, “and knows just as well as I do that I mean she is not to touch the vase.”

“Yes,” said Papa Dick, “and because she is a little human being she will some day investigate that vase for herself.”

MARY ELLEN DIDN’T LIKE WATER.

And now that day had come. Mary Ellen sat for a time on the rug after her mother went out, holding her rag doll by one leg. Suddenly she dropped the doll and made vigorously for the mirror. She didn’t hesitate a second after getting there. She reached for the biggest rose of the lot, grabbed it by its head and pulled. Over came the vase, crash, splash, drench! Mary Ellen gazed at the puddle. She didn’t like water. When it spread out and wet her dress, she struck at it and drew herself away. “Notty watty!” she said. This amused the parrot and he laughed. “Notty watty!” she cried, looking up at him, and struck at it again. Mary Ellen had never seen anything struck, but it was a very fierce little blow she gave the puddle of drenched flowers. Then she set off with her big rose for the open door into the hall, and up the stairs she went, and nearly twice as quick as on the day before.

Ella Farman Pratt.

“No Kit, no toys. I think children don’t need their toys at the beach.” So said Kit’s mother.

Poor little Kit laid down the armful she had fetched to the trunks. “How will I ’muse me?” said she mournfully.

“O,” said her mother cheerfully, “there is a wonderful seashore plaything which I shall buy you.”

All the way Kit thought about this “plaything.” It proved to be a little blue wooden pail and a spoon.

Kit had never seen outdoors sand before. “Nurse,” said she, “Is this sand all sc’ubbing sand?”

KIT AND HER PRECIOUS PAIL.

The little blue pail was truly a “wonderful plaything.” Kit forgot doll-house and dolls. She was world-building—mountains and caves and rivers and seas; wells and “little homes” for star-fish and sand-crabs; great treasure-vaults for shells and pebbles; gardens of sea-weed. Other children had sand-pails. Some days they toiled in company, and built long lines of forts. Other days they built large cities. One boy dug a deep well and called it an “oil well.” He sunk a small tin cup of kerosene in it and put in rags and set it afire with a match, and the whole little crowd jumped up and down and shouted. But Kit’s mother and other mothers put it out and said it was wrong.

On the last day of all Kit filled her pail with “sc’ubbing sand” to carry home.

Louise Kendrick.

Not one of the grandmothers heard Mary Ellen on the stairs or on the landing, and the little creature patted along by the wall in her pretty red slippers, past the door where she had tumbled in the day before, past Madam Esther’s, and turned into the other hall with her rose. This hall was lighted by a large window, and as Mary Ellen felt the sunshine full in her face she began to smile and look like herself again. She pattered along faster, smiling and smiling, and just as she came to the last door was on the point of exploding into a whole fireworks of laughs and crows and calls, as was her way when very much pleased.

“Gum-um!” she called, but first running into the corner and backing up close against the wall. Mary Ellen had no notion of falling in when this door opened.

It was at Old Lady Lois’s room that she had stopped, as she her little self knew very well. The door opened instantly. But the dear old great-grandmother did not see the child at first. She looked all about her, as if very much alarmed.

“Yosy!” Mary Ellen cried out. “Yosy, Gum-um!” She toddled forward and held up the big wet rose.

Old Lady Lois gathered her up in her arms and went in. “Are you up here again, child?” she said, reproachfully.

“Yosy,” said Mary Ellen. “Yosy.”

“Yes, pretty rosy,” answered Old Lady Lois.

“Yosy!” persisted Mary Ellen.

“YOSY!” SAID MARY ELLEN.

“You best take the flower, Mrs. Gray,” said Mrs. Camp. The others had heard the chirping of the little voice and had come in to see what had happened.

“Don’t you see she has brought it on purpose for you? I told you she would know us apart. I knew she would know you by your flower! She must have been very observing when her mother has had her up here, to know which was your room.”

“Yosy,” said Mary Ellen, pushing the wet flower up against the gentle old face. This time Old Lady Lois took the rose and pinned it in her kerchief. She looked very pleased. The child seemed satisfied now. She laid her little yellow head back on the white kerchiefed shoulder and looked around on the others.

“I shouldn’t be surprised,” said Mrs. Persis, contemplating her, “if she has broken the vase getting the rose out. Her dress seems very wet.”

“Notty watty,” said Mary Ellen.

Madam Esther had gone down-stairs. She came up now with Mary Ellen’s father and mother. Poor Mama Nan seemed even more terrified and breathless than on the day before. “I told you I should never know another moment’s peace,” said she.

Papa Dick laughed at her. “You ought to feel relieved,” said he. “Here your smart little Mary Ellen has taught herself, all alone, how to go up-stairs.”

But Mama Nan was not to be comforted in that way. “What is to be done?” said she. “She will undertake this thing every day.” And here she quite broke down and began to sob in a miserable helpless way.

Nobody spoke for a minute. Then Great-Grandmother Day said gently, “Just let me take her in charge, Nancy. I promise you the child shall soon go up and down with perfect safety.”

Mama Nan started up in fresh terror. “She has got to learn how to go down too? Oh, me!”

MARY ELLEN LOOKED AFTER THEM.

“See here, Nan, you better come down-stairs,” said Papa Dick, a droll look about his mouth.

They went out, leaving Mary Ellen with her grandmothers. She sat up and looked after them, with big eyes. “Mama k’y!” she said.

Ella Farman Pratt.

TEACHING MARY ELLEN.

“Getting down-stairs,” said Great-grandmother Day, “doesn’t come so natural to a child as getting up-stairs does. And there is more danger about it. Mary Ellen ought to be taught how to do it, and then be watched. And the sooner the better, for evidently she is coming up here when she pleases.”

The venerable lady stood her cane up in a corner, took Mary Ellen from Old Lady Lois’s lap, gave her a finger and toddled her along to the staircase, and placed her on the floor, her little back to the stairs. Then she stepped down. “Come,” said she, “let’s go down-y, down-y, down-y!”

“See, she is going,” said Mrs. Persis.

But not exactly going was Mary Ellen. Great-grandmother Day had taken hold of her ankle, and was seeking to draw the little red-slippered foot down to the first stair. Feeling herself going, she knew not where, Mary Ellen began to scream, then threw herself flat on the landing.

“Mercy! I hope Nan doesn’t hear this!” said Mrs. Camp.

“She doesn’t,” said Mrs. Lee. “Dick and she have just driven out of the yard.”

Mrs. Day straightened herself up, with a red face. “She will do it all right in a minute or so,” she said. “Babies are born with instincts to do these needful things, just the same as cats and colts.”

After a long breath or two, Mrs. Day bent down and tried again. But Mary Ellen was really terrified, and screamed louder than before. This time she kicked too, and so hard that her poor Great-grandmother had to let go.

“Notty Gum-um!” cried the child.

“Turn her round,” said Mrs. Camp. “Perhaps her ‘instinct’ is to go frontwards. Nan’s was.”

And when Mary Ellen was turned, and could see what she was doing, and where she was, and Mrs. Day coaxed again, “Down-y, down-y, now!” the wonderful “instinct” began to stir. She held on to the landing, behind, with both hands, gave a quick hitch, and set her little self on the next step below all right. And down they got her at last, with great fun.

“Nan used to go down that way, so fast she seemed to be just sliding down,” said Nan’s mother, “and now she is so scared about Mary Ellen!”

A BABY NO LONGER.

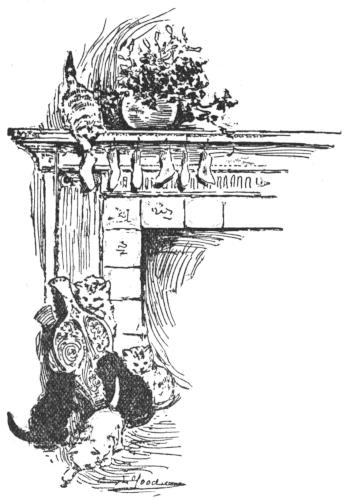

Well, the day came at last when nobody was worried to find Mary Ellen going up or coming down quite alone, holding to the baluster by one hand, and perhaps a cat on the other arm. She visited first one and then another of her grandmothers, never making two visits on one trip. She seemed to be led by the kind of play she had in her little mind. In Mrs. Persis’s room it was the cat-basket, and a frolic with the cats. In Great-Grandmother Day’s it was to ride the cane cock-horse, like a little boy, thumping it about with plenty of noise. Some days she had a flower to carry to “Yady Yois.” She went up to Mrs. Lee’s room to look at pictures. In Madam Esther’s she picked up buttons; when Madam Esther, who loved quiet, heard the little red slippers stopping at her door, she hurried to overturn her button-box. In Mrs. Camp’s room the little visitor “made moosic” on the guitar strings.

It was to get for “Yady Yois” a big red dahlia that had blossomed by the gate, that one day, all by herself, Mary Ellen clambered down from the veranda, and took her first journey out into the world. She ran skipping over the green grass, tossing her little arms and singing “da-da! da-da!” at the top of her voice. Her yellow hair was blowing all about her face and shining in the September sun and wind.

Her father caught her up, as he came in through the gate. “O, ho!” said he. “Running away, is she? Not a baby any longer, but an independent little girl!”

Ella Farman Pratt.

They called her “Little Sun-bonnet.” I will tell you why.

BETH.

Her mama had promised to take her to a picnic, and for days little Beth could talk of nothing else.

The night before the picnic day Beth had caught sight of little round cakes, tarts, and a Washington-pie on the pantry shelf, and when her bed-time came, and she was up in her little room with mama, she asked so many, many questions that at last mama said:

“There, there, dear, you must go to sleep, so as to wake very, very early in the morning.”

After mama had left her, Beth lay for a long time thinking; and this awful thought came to her: suppose she shouldn’t wake “very, very early,” and so have no time to get dressed for the picnic!

In a twinkling Beth was out of bed. She pulled on her stockings. She buttoned the six buttons of each small boot, and as many buttons of her dress as she could reach. Then she felt around in the dark for her pink calico sun-bonnet. This she tied tightly under her chin. Then she crept softly back into bed.

How mama laughed when she came into her little daughter’s room in the morning! And how everyone else laughed! And now you know how Beth came to be called “Little Sun-bonnet.”

Carrie A. Griffin.

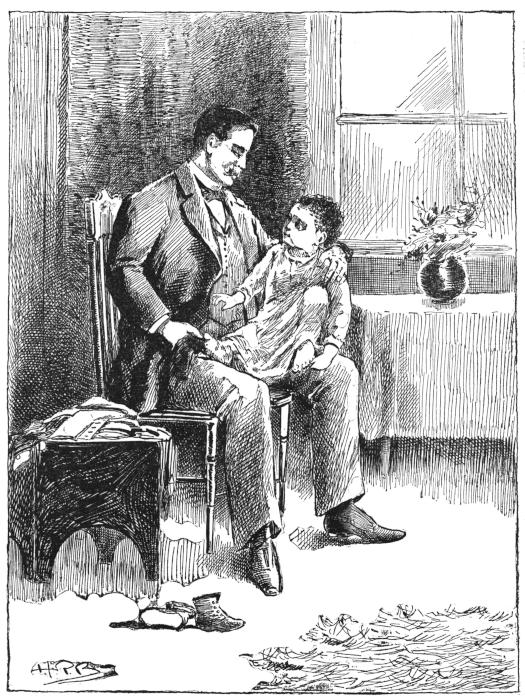

Jack came trotting into papa’s room one morning with two little black stockings in one hand, two little black boots in the other, and several small articles of clothing over his shoulder.

“STOP, PAPA! STOP!” CRIED JACK.

“Papa,” he said, “does you know how to dwess yittle boys? Gumma’s gone.”

“Yes, indeed, my little man,” said papa; and he lifted Jack to his knee, and began to pull on one small stocking.

“Stop, papa! stop!” cried Jack. “Dat ain’t a-way! Gumma don’ do it dat-a-way!”

“Well, how does ‘Gumma’ do it?” asked papa, pausing for instruction.

“Dis-a-way,” said Jack, taking up one foot and then carefully grasping a fat toe in his chubby hand.

“Here, Mishter Toe, you an’ your bruzzers mus’ go into your yittle black house; now don’ begin to w’iggle. One, two, free, dere—you go!” and Jack pulled his stocking over his five toes, and up to his knee. Then looking up into his papa’s face he said: “See?”

“Yes,” said papa, smiling. “Here goes the other foot. Now, Mr. Toe, you and all your brothers”—

“No, no, papa!” cried Jack; “dat one is Mishis Toe, an’ you mus’ say, ‘all your yittle sissers.’”

“O, ho!” said papa. “Well then, Mrs. Toe, and all your little sisters! One, two, three, there you go!” and the second stocking was on.

“Now,” said Jack, “you mus’ put on the woof.”

“The what?” asked papa.

“The woof to the house,” and Jack pointed to his boot.

“Oh! the roof. Very well,” and papa put on the boot and begun buttoning it with his fingers.

“Dat ain’t a-way!” cried Jack again. “You mus’ get a hooker and lock all ’e’ doors, so all the yittle bruzzers and sissers won’ get out ’e’ house for all day.”

“Now see here, young man,” said papa, “does grandma go through with all this rigmarole every morning?”

“Of courth,” said Jack, looking at papa with surprised eyes.

“Well, papa hasn’t the time, so let me get you into your clothes quick, before the breakfast bell rings.”

So Jack had to submit to being dressed in a hurry, without his grandmother’s pleasant romancing.

The minute he got downstairs he went to his mama and asked:

“Fen’s my gumma comin’ home?”

“She is coming to-morrow,” said mama.

“Dat’s nice,” said Jack, “for” he whispered into mamma’s ear, “my papa don’ know how to dwess yittle boys.”

Carrie A. Griffin.

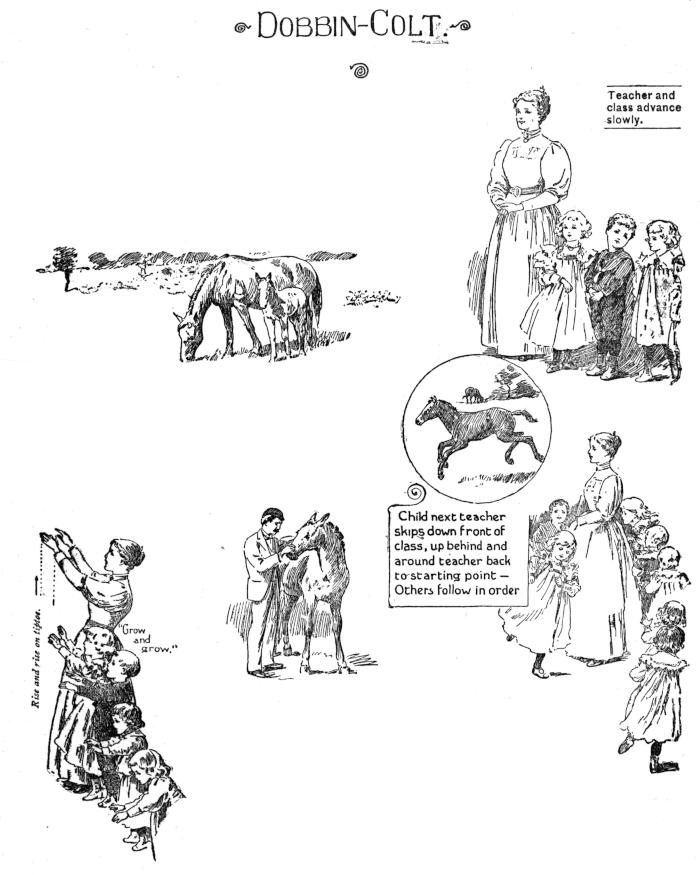

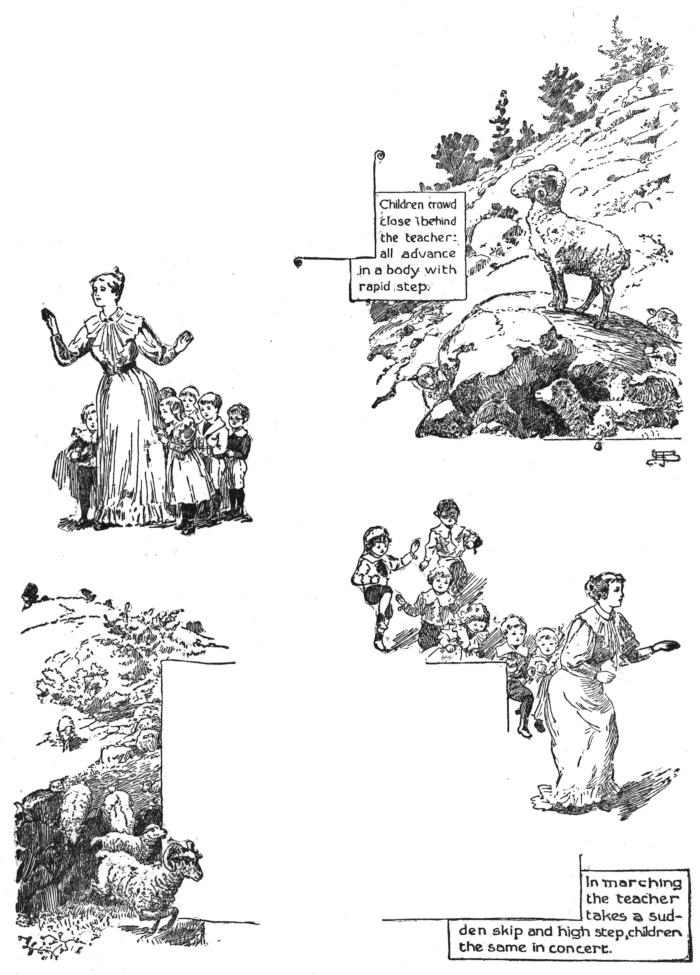

Teacher and class advance slowly.

Child next teacher skips down front of class, up behind and around teacher back to starting point—Others follow in order.

“Grow and Grow.” Rise and rise on tiptoe.

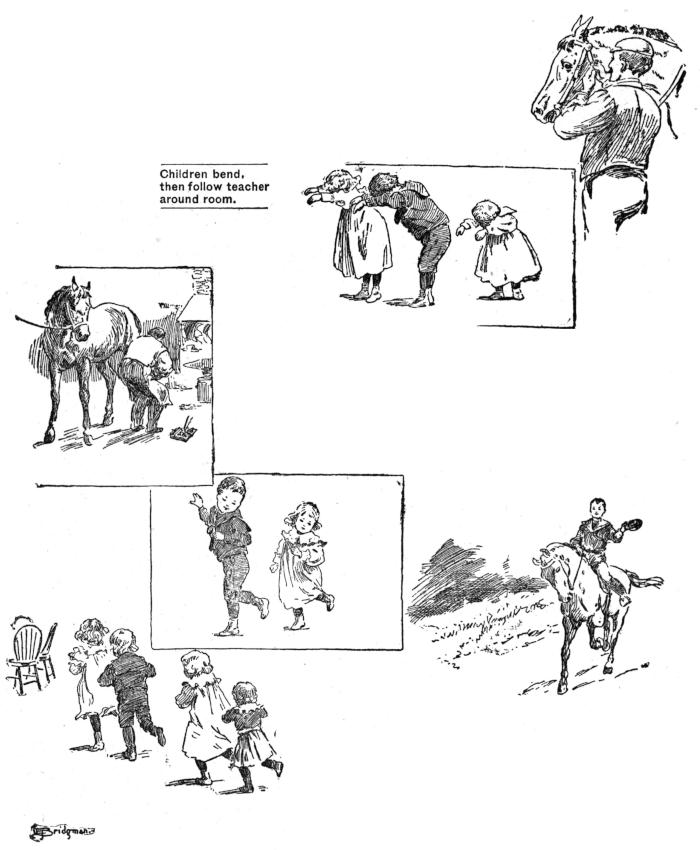

Children bend, then follow teacher around room.

In this play the children should wear little bells on ribbons.

Children follow teacher, single file, slowly, in winding line.

All pause in semicircle, bend heads, drink from hollowed palms, then follow teacher back, bending and moving heads from side to side as if cropping grass.

Children crowd close behind the teacher: all advance in a body with rapid step.

In marching the teacher takes a sudden skip and high step, children the same in concert.

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

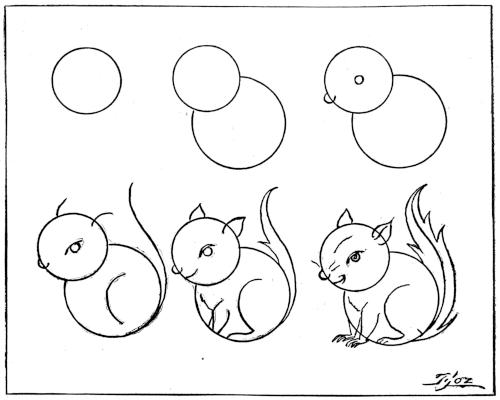

First, find two pennies, one small, one large (or, if a big old-fashioned copper cent is not to be found in papa’s pocket, a two-cent piece, or a silver quarter, will do as well). Then take slate, or paper, and pencil, and draw a small circle and a large circle, as in the first and second pictures. To these lapping circles, add eye, nose, mouth, ears, legs, feet, and last of all a fine bushy tail—and, behold! the nimble pennies have changed to a gay little Christmas “nut-cracker”—which everybody knows is one of the squirrel’s nicknames.

P. S. C.

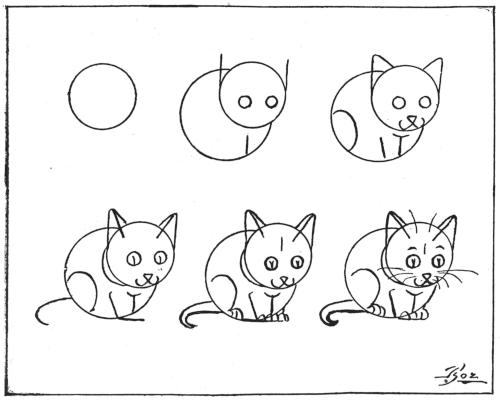

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

Through the year “The Nimble Pennies” will open the gates to a cunning menagerie for the little nursery girls and boys. Ask papa or mama for two cents, one small and one large (a two-cent piece, or a silver quarter, will do as well if a large copper cent is not to be had). Draw circles around the pennies, as in the first and second pictures, then add eyes, nose, mouth, ears, legs, feet, tail, and last of all whiskers—and, lo! the pennies have nimbly changed to a cat!

P. S. C.

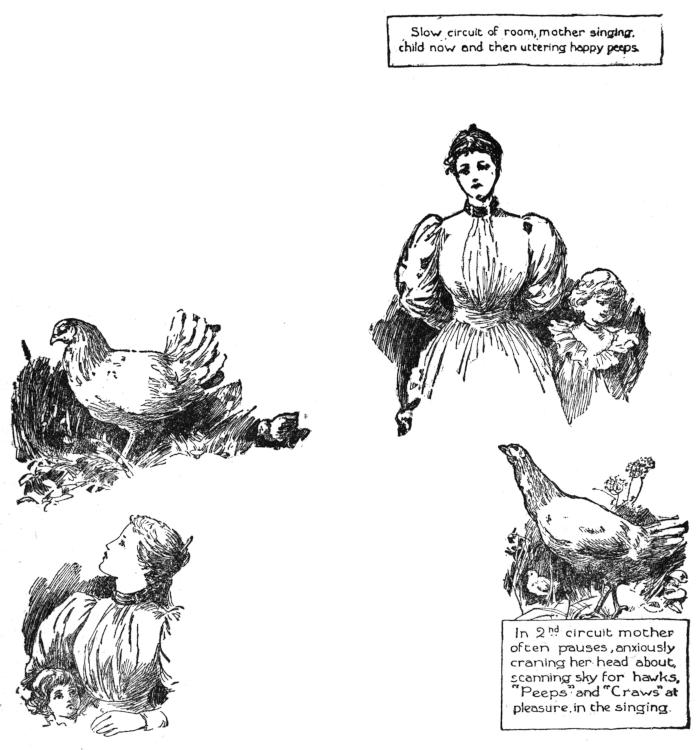

Slow circuit of room, mother singing, child now and then uttering happy peeps.

In 2nd circuit mother often pauses, anxiously craning her head about, scanning sky for hawks, “Peeps” and “Craws” at pleasure, in the singing.

3d. circuit is interspersed with running steps and darts of the head. Child runs at all “calls” with outstretched arms and chirps.

In the 4th circuit, side by side they sip from hands, uplifting heads at each swallow. Finish circuit, child walking behind mother.

After the little boys were all snug in bed for the night, Norah would go in to put out the lamp. And this is the story she would tell them, while they leaned on their elbows and watched her face closely, for “it’s a seeing story as well as a hearing story,” Teddy said.

THE WAYS NORAH LOOKED.

“Once there was a man, and he looked just like this,” and Norah twisted her under-jaw around to the right. “And his wife looked like this,” and Norah twisted her jaw to the left.

“And they had a boy who looked like this,” and Norah drew her under-jaw in back of the upper one; “and a girl that looked liked this,” and Norah threw her under-jaw out beyond the upper.

“And they had a dog that looked like this,” and Norah pursed up her mouth to look like a round “O.”

“When it was bed-time the family wanted to blow out the candle.

“And the man would blow like this,” and Norah puffed out of the right corner of her mouth, “but he couldn’t do it.

“And his wife would blow like this,” said Norah, puffing out of the left corner, “but she couldn’t do it.

“And the boy would blow like this,” and Norah threw back her under-jaw and blew downwards, “but he couldn’t do it.

“And the girl would blow like this,” said Norah, throwing her under-jaw forwards and blowing upward, “but she couldn’t do it.

“Then the dog would come along and blow like this.”

Out went the light!

“Good night,” said Norah.

The little boys always laughed then, and cuddled down to sleep.

Mattie W. Baker.

“WHICH IS THE TALLEST?”

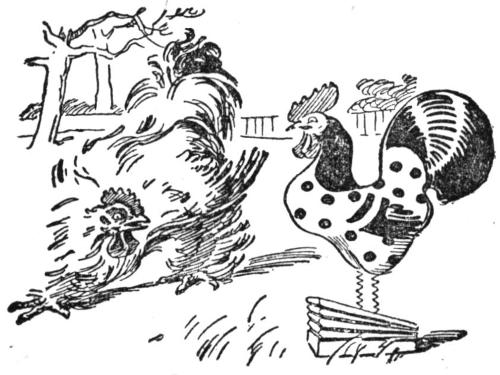

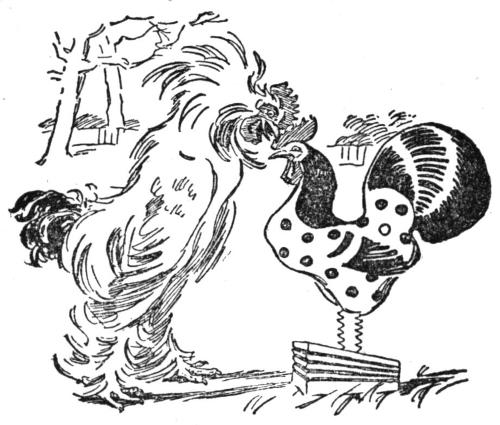

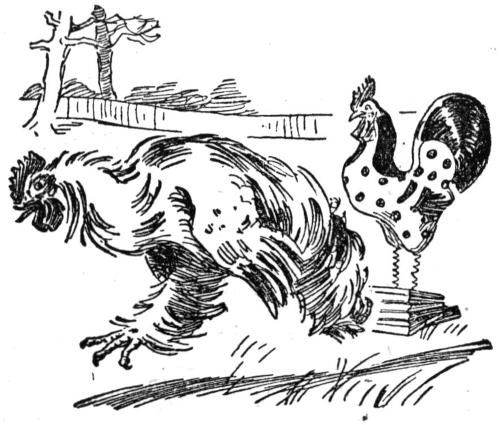

One day Baby left his rooster-toy out on the grass, and there he stayed all night.

THE BRAHMA DREW BACK.

Soon after sunrise the White Brahma cock came out for a walk, and his eye fell on the stranger. “What’s this?” said he, drawing back. He noticed the gold spots on the stranger’s breast, and his curling green and blue tail feathers, and his wrath rose. “I’ll curl his impudent feathers!” said he, and flew at him prepared to tear his comb out by the roots. The stranger did not show fight and was borne down, yet began to crow, and gave out such a string of victorious cock-a-doodles that the White Brahma turned and ran for his life. He did not know what Baby knew—that if you bore the rooster-toy down hard he would cock-a-doodle six times running.

THE BRAHMA FLEW AT HIM.

THE BRAHMA RAN.

John Peters.

P. S. C.

“SORRY-BOY.”

M. D.

On July third Percy’s mama went up to wake him.

He cried out when she kissed him, “Oh, mama, I was having a splendid dream! I had just put eighteen packs of fire-crackers in a barrel under your window, and set them off, and they were just going to bang!”

“Never mind,” said mama, laughing. “You will get all the bang you want to-morrow.”

About ten o’clock mama missed Percy.

There were “symptoms” of him everywhere; his little straw hat on the hall floor, his top in the dining-room, his cars in the parlor, his dog in the porch, his bicycle down by the front gate. But no Percy.

Finally she went upstairs, and there was Percy stretched out on his little brass bed, his eyes shut tight.

“Why, Percy,” said mama, as she bent over him, and he opened his eyes. “Are you sick?”

“No, Mama, but it’s a dreadful long time till to-morrow, and I was trying to piece out my dream so’s to hear the bang! Oh, I’m so sorry you woke me up this morning!”

L. E. Chittenden.

AND THAT’S FUN YOU KNOW!

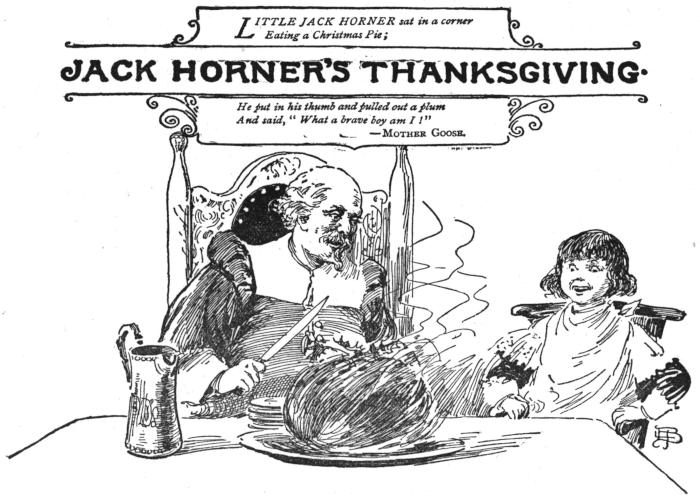

PLUMS FOR BOTH THUMBS.

—Mother Goose.

Clara Doty Bates.

Little Posy Pinkham always declared her cat un-der-stood what she said. I could tell little children many things to show that house-cats and house-dogs do un-der-stand much that is said, and some day I will.

One morning Posy came running downstairs, eager to tell her mama what she had dreamed, and Posy’s cat at once pricked up her ears to listen, for she, too, had had a dream. Any child who watches a cat asleep knows cats dream.

“What makes me dream, mama?” asked Posy.

“O, things you talk about, hear about, and think about.”

“Meow-wow! ou-ou-wow!” remarked Posy’s cat. She was saying that now she understood the reason of her own dream.

Posy’s cat had a very short, stubby tail, while she liked very much better to see long glossy tails, and wished every day of her life that her tail was long and handsome.

In her dream she was sitting on the gate-post, and had a long glossy tail that reached all the way down and lay on the ground, and was so beautiful that rats came into the yard to look at it and admire it.

“I wish dreams could come true,” said Posy.

THE DREAM.

“Ow-wow-ow!” said Posy’s cat; that meant, “I do too.”

Laura Hewells.

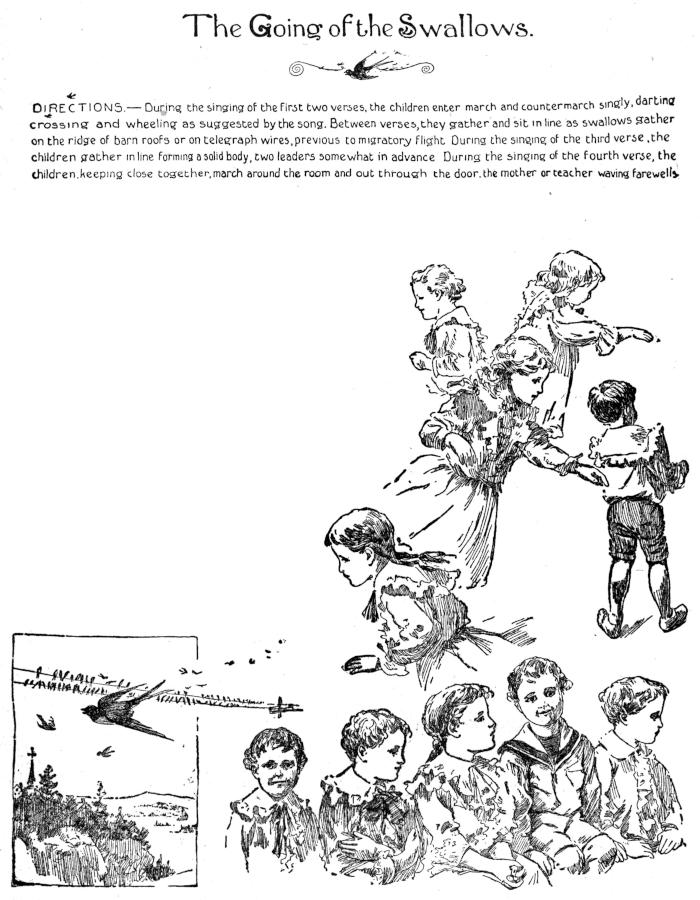

DIRECTIONS.—During the singing of the first two verses, the children enter march and countermarch singly, darting crossing and wheeling as suggested by the song. Between verses, they gather and sit in line as swallows gather on the ridge of barn roofs or on telegraph wires, previous to migratory flight. During the singing of the third verse, the children gather in line forming a solid body, two leaders somewhat in advance. During the singing of the fourth verse, the children, keeping close together, march around the room and out through the door, the mother or teacher waving farewells.

(Mother or Teacher sings:)

(Children sing:)

(Mother sings:)

(Children sing:)

(Mother sings:)

(Children sing:)

(Mother sings:)

(Children sing:)

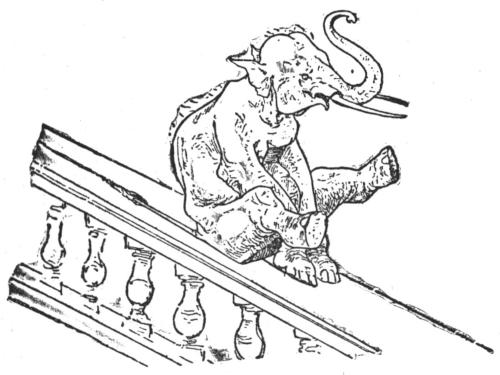

One day when the Show was passing through a village, one of the young trick-elephants heard a little boy laugh out suddenly. This elephant liked little boys; he had a roguish look himself and could take a joke, and never acted “mad” when some mischievous little visitor fed him an empty peanut shell.

THE YOUNG ELEPHANT’S DREAM.

Turning his mouse-colored head, the young elephant looked in at the open door of the house they were passing. He flapped his big ears at what he saw there, and laughed too.

That night when the show was over, and he stood in a row with the other elephants going to sleep, he thought again of what he saw in that open door, and laughed once more. “That must have been fun!” he said to himself. “It must be fun to be a little boy! That trick was funnier than any we circus elephants are taught to do. I wouldn’t mind being a little boy myself! I truly wouldn’t!”

And then the jolly young elephant went to sleep, and dreamed he could do the little boy’s trick—and really he never enjoyed a dream so much before in all his life.

George Dutton.

Heads drooped, eyes closed, hands on knees.

March forward slowly in line, diverging.

March down to the end of the room, heads held high. Sing with emphasis.

(Teacher sings.)

(Teacher sings.)

(Teacher sings.)

(Children join in.)

Turn, sing, right arms lifted like imperious paws.

March around the room rapidly, tossing heads, pursuing teacher, or mother, who “falls in” at the right point, keeping in advance.

March around the room again. “Take the prey” by overtaking and surrounding the teacher, or mother.

(Children sing.)

(Teacher sings.)

(Children sing.)

Grey Burleson.

If a Polar bear went upright, he would be as tall as a man with a boy standing on his head.

But the Polar bear goes on all-fours, and so he is nine feet long instead of nine feet tall.

A big white Polar bear lived at the Zoo—a place where wild animals are kept—in London, twenty-three years. He was named Zero, because he came from the cold Arctic regions. It was so much warmer in London that he was given great cakes of ice to lie on.

Zero weighed nearly a ton; but, though he was so large and so long, his tail was very, very short, as short as a goat’s tail.

Unlike all other bears, the Polar bear’s feet are shod with hair—short hairs set so close that one can’t see between them even with a magnifying glass. With this hairy sole to his feet, the Polar bear can walk on the smoothest ice without slipping.

Crowds of little London boys and girls used to go to the Zoo to watch Zero splash into his cold-water swimming-bath. Zero liked his swimming-bath best of anything in London—that and the ice. He never noticed the children at all.

Polar bears are fondest of fish for food. Zero was also fond of strawberries, but he would not touch the buns and apples the children tossed in between the iron bars of his great cage.

C. P. Stuart.

THE NIMBLE PENNIES.

Draw a small circle, and then a large circle at the right of, and behind, the other—as in the first and second designs. (Use a small cent and a large copper cent, or two-cent piece, or silver quarter.) Then add the lines in the third, fourth, fifth and sixth designs—and you will have a very tame bear wearing a muzzle.

P. S. C.

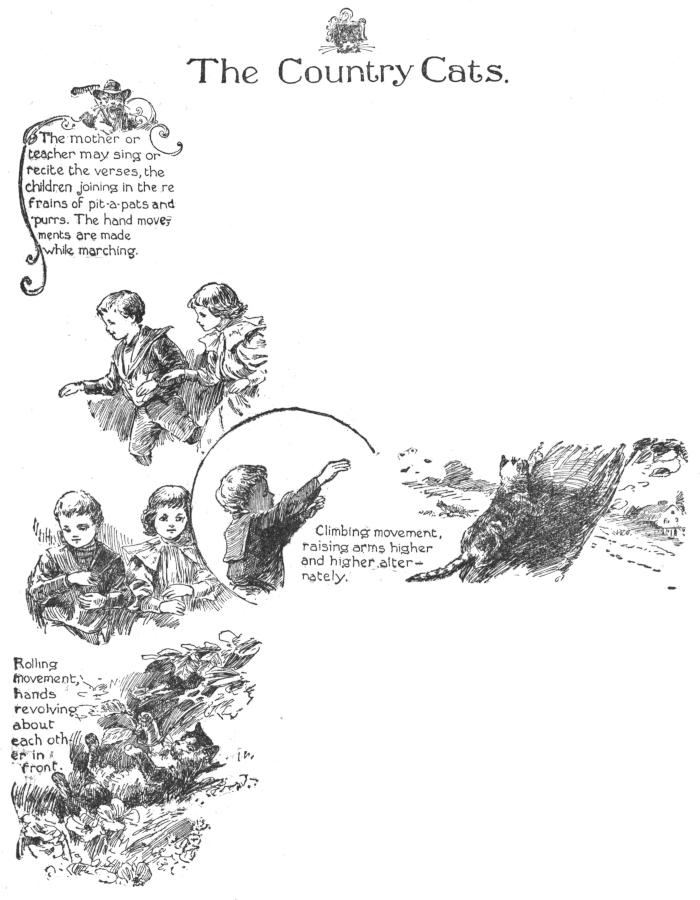

The mother or teacher may sing or recite the verses, the children joining in the refrains of pit-a-pats and purrs. The hand movements are made while marching.

Climbing movement, raising arms higher and higher alternately.

Rolling movement, hands revolving about each other in front.

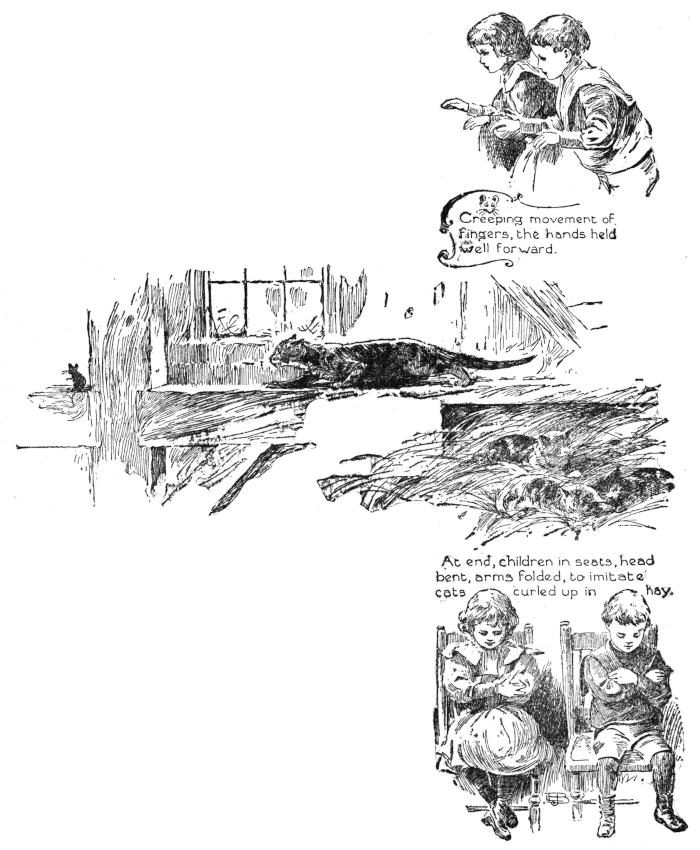

Creeping movement of fingers, the hands held well forward.

At end, children in seats, head bent, arms folded, to imitate cats curled up in hay.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.