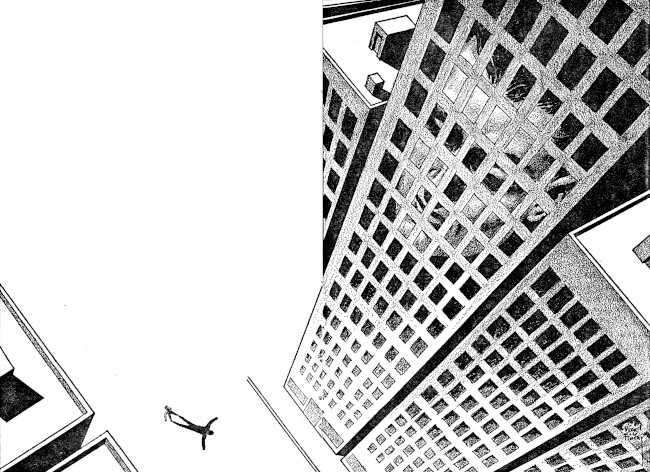

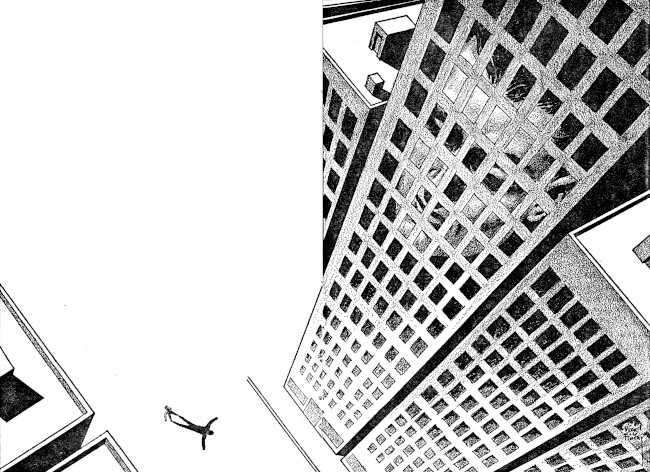

By HERBERT D. KASTLE

Illustrated by FINLAY

Mercy Adrians was 19, and good to look at.

Edwin Tzadi was of undetermined age and not

good to look at. Derrence Cale was a phoney.

But at least, he thought, he was a man.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories December 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Derrence Cale walked into the glittering tile, marble and metal lobby of the Chester Chemical Company Building at a quarter to nine. Office hours were nine-fifteen to five-fifteen, but Derrence came early and left late every day. He unlocked the doors to the Public Relations department, checked to see that the custodial staff hadn't left any rags or buckets around and, in general, fulfilled the duties of floor manager.

Not that Derrence had been assigned these duties. He'd assumed them over the past eight years, and because Chester Chemical was as big as it was, he got away with it. Derrence had effectively hidden himself among the 9,000 Chester employees; lost himself, as so many talentless but shrewd people do, in the hive of offices that make up a giant corporation. That was why he was able to draw a salary, and merely play at working.

He was alone in the self-service elevator when it shot upward. He was alone when he stepped out on the 36th floor. But after unlocking the doors across the hall from the reception room, he was immediately aware that he was not alone.

From down the long, pastel-green, fluorescent-lighted corridor on his left had come, and still came, the sound of a voice. A high-pitched male voice, totally unfamiliar to Derrence Cale. There was no answering voice, so the man was using a phone.

It could only be one of the cleaning staff; and they'd been warned by management never to use office equipment.

Derrence strode toward the voice, heels clicking sharply on the black squares of asphalt tile. The voice stopped. Aha, a little game of cat and mouse, was it? Derrence kept going, watching the seemingly endless line of offices on his right for one with its door open or a light shining through the frosted glass panel. And he saw the light in the office ahead.

He stopped, his long, smooth face crinkling in a swift smile. He took a quick, silent step, and jerked open the door. The man seated behind the desk was middle-aged, fat and solemn. He had bright blue eyes and jet black hair. "Good morning," he said in his high-pitched voice. "I'm Mr. Tzadi." He smiled. "I'd better spell it." He spelled it. "Edwin Tzadi. This is my first day."

So that explained it, and Derrence was ready to back out as gracefully as possible. But then he noticed how meek Tzadi seemed, and decided to stay a few moments. He came forward with hand out-stretched. "Welcome aboard, Ed. I'm Derrence Cale. Der to you." They shook hands. "New writer, eh?"

Tzadi nodded and smiled.

Derrence put his hands behind his back and rocked on his heels. "Personnel never bothered to inform me that you were coming. I'll have to check Miss McCarty. She may have heard and forgotten to mention it."

"Is she your secretary?"

Derrence said, "Not exactly," and regretted having given into his impulse to act important. "Well, work's awaitin', as they say in the Ozarks." He chuckled. "Though for future reference, Ed, you needn't come in until nine-fifteen. The hours at Chester Chemical...."

"Yes, I know, but I am an early riser. I will be here each morning at eight-thirty, perhaps earlier."

Derrence decided he didn't like Tzadi. There was something vaguely foreign in the way the man spoke. Not that he had an accent. It was more a matter of off-beat timing. And that name—Central European in origin. Personnel was getting sloppy.

"I'm afraid that's not feasible, Ed. At eight, the cleaning people leave, locking the hall doors. Miss McCarty and I have keys, but we couldn't allow them out of our possessions. (He'd waited three years before borrowing Miss McCarty's and having a copy made.)

"I too have a key." The fat man beamed. "That solves our little problem, doesn't it?"

"How'd you get...." He stopped short. Time to leave. Should never have come in here in the first place. This man isn't an ordinary writer!

"Is there anything wrong, Der?"

Derrence smiled. "Wrong? Of course not. Just thought of an urgent bit of business. Again, welcome aboard, Ed."

"And again, thank you, Der." Tzadi smiled, somewhat apologetically. "And again, that question."

"What question?"

"Is Miss McCarty your secretary?"

"I answered it," Derrence said, and found it hard to smile. "I said she wasn't."

"No, Der," Tzadi said, right hand rising, index finger lifting scholastically. "You said, and I quote, 'Not exactly.' That indicated semi-secretarial status."

Derrence was immediately frightened. He fought it by telling himself he was jumping to conclusions. There was no reason in the world to assume that the man was a company spy, especially since Chester Chemical never had been known to employ such methods.

He laughed. It was a rich, hearty, booming, self-confident laugh, developed by means of long practice with a tape recorder. Hearing it, he was able to form an answer. "Actually, Ed, Miss McCarty is the floor manager. She assigns new offices ... as she did this one to you, right?"

"No. Mr. Chester said to choose any empty office that pleased me."

Mr. Chester! The Founder himself!

Derrence opened the door and waved his arm and chuckled and nodded and exuded good will, and said, "See you, Ed."

"Der," Mr. Tzadi said, rising. He was extremely short; not more than five feet, if that. "If Miss McCarty is floor manager, what are you?"

"No title, per se," Derrence said, and was horrified to hear his shortness of breath, his panicked panting. He fought for control. "I ... work with her. The arrangement is loose, informal, almost unofficial. A typical Chester Company operation." He had the door open now, and stepped through it sideways. "You'll soon learn what that means, Ed. We all stay loose here. No rigid adherence to rules. No frenzied competition. No sweat. Get it?"

Mr. Tzadi's face looked blank. He shook his head. "I am afraid not, Der. Mr. Chester said that each employee has a position, a function, a title, and performs within sharply defined areas. I am listed as Public Relations Writer in the Personnel books. You too are listed as Public Relations writer, eleven thousand dollars per annum."

A tortured laugh was forced from Derrence Cale. The man had revealed himself as a company spy! Who else had access to the Personnel records? He waved his arm again, said, "Simply must rush," and fled.

His office was at the other end of the floor from Tzadi's. He reached it, shut the door and slumped into his chair. He was trembling. This was the first time in almost six years that anyone had shown true knowledge of his position. The last time had been when old Halvertson, his group head, had called him in and said, "Derrence, your work's falling off badly. I'd be justified in recommending you for discharge right now, but I want to give you a fighting chance. We've got the new polio vaccine pamphlet to do, and an important fact sheet for distribution to newspapers. I'll be watching you carefully." But he hadn't. He'd dropped dead two days later while walking to the men's room. When word came that Halvertson's group was being dissolved and his writers assigned to other groups, Derrence had decided to make his move. Besser and Trance had been assigned to Gordon. Pete Ward had come to Derrence's office and said, "While I don't really need an extra man, Cale, you're supposed to be assigned to me." Derrence had expressed delight ... "but I've got quite a bit of work to clear up before I'm free, Mr. Ward." Ward had seemed relieved. "Yes, well, carry on, Cale." Derrence had carried on for three months; then Ward had been promoted upstairs, and the man who took his place never even spoke to Derrence. Derrence carried on and on, creating the impression, which soon hardened into fact, that he was now overseeing Miss McCarty in her position as floor manager. Since he was careful to please and flatter her, and meticulous in maintaining the routine which kept him outwardly busy, he'd never again been asked to report to anyone, work for anyone, account to anyone. As for his salary, it was handled by total strangers—the Fiscal department on the 17th floor, which was as remote from the 36th floor as interior New Guinea. Now this Tzadi came along, and soon the lovely, secure life would go down the drain. And what would he do then?

His face went gray, and he whispered, "I could go back to writing...."

He groaned. It was impossible! He couldn't write. He couldn't even sit for the hours necessary for writing!

A deal. He had to make a deal with Tzadi. Twenty a week for as long as he was allowed to go on this way. Or thirty. Maybe even forty.

"Or kill the dirty little...."

His voice, hard and shrill, shocked him. He was standing, fists clenched, body trembling, leaning forward as if about to rush to the door and up the hall.

He made himself sit down. He laughed, but it didn't come out his hearty, impressive laugh. It was a laugh he hadn't heard since college days (except in dreams; nightmares of the past)—weak, frightened, ineffectual and apologetic.

There was a knock at the door. He straightened in his chair, took a deep breath, said, "Come ahead."

The door opened. Mr. Tzadi stood there, his round face solemn. "Before you become too involved in your numerous and important duties, Der, I would like to suggest that we have lunch together."

Derrence blinked. "Yes ... how about today?"

"Today would be fine, Der. We could talk about the company and our respective positions. You could, perhaps, help me with a rather pressing problem."

Derrence relaxed quite suddenly. "Twelve o'clock. Come by here?"

"Yes, Der." The door closed.

Derrence lit a cigarette. He no longer trembled. In that luncheon invitation he read a deal.

At noon, Tzadi appeared in the office doorway. Derrence was dictating a memo to Personnel on the company's tacit acceptance of two-hour lunch periods by all but secretarial help. He broke off in mid-sentence and smiled at Mercy. "We'll finish later, dear. You've typed those other memos, haven't you?" Mercy said, "Most of them." She rose and turned to the door, and only then saw Tzadi. She said, "Hi, Ed," and walked by him and out of the office.

Tzadi came inside. "Lovely young lady." It was a remarkably mild comment compared to what most of the writers said when watching Mercy swinging along. She was nineteen, and very good to look at—especially from the rear. Which was further proof, if any were needed, that Tzadi was the company spy type; not likely to be swayed by emotions that moved other men. Yet he wanted something; of that Derrence was sure. It could only be money.

"Yes," Derrence said. "I keep her busy. Memos, memos, dozens of memos." Which was the truth, except that once Mercy brought him the memos, neatly typed, he tore them into small pieces and filed them in his waste basket.

"Is she dependable in her work?" Tzadi asked, looking as if he were thinking of other things.

"I thought you knew her. She seemed to know you—calling you by your first name."

Tzadi blinked his eyes. "I met her this morning. You know these young girls—friendly as kittens."

Derrence nodded, but maintained his smile. Mercy only looked like Venus. Actually, she was shy and reserved, especially with strangers. For her to say, "Hi, Ed," required a minimum of several weeks acquaintanceship. That meant she had met Tzadi before he came to this floor. That meant she was—unwittingly, perhaps—an accomplice of Tzadi's. Which in turn meant that the fat man had all the information he needed to get Derrence fired. But it no longer bothered Derrence. He and Tzadi were going to make a deal. He would bet his life on it.

They walked into the hall. Derrence said, "Well, Ed, it's going to be a long, interesting lunch. Shall we splurge and try Manfredo's? They have a degree of privacy which, I'm sure, we'll both appreciate."

Tzadi nodded. "Whatever you say, Der."

"I say Manfredo's." He chuckled. Might as well make the best of it. So his comfortable life was going to suffer changes. So the brandy wouldn't be the best, and he'd buy his suits on sale, and he'd lunch three or four times a week in the company cafeteria. It might even mean giving up his beloved Sutton Place apartment. But he'd still be better off than if he had to hunt for a new job ... and actually work.

They started with vodka Gibsons. Derrence gulped his, and was ready for another. Tzadi, however, merely sipped once, and then read the menu. Derrence decided he couldn't relax too much. There was going to be some hard bargaining. Tzadi said, "It's very nice here, but rather expensive. I would like to be able to afford Manfredo's, but I doubt...."

"What do you earn?" Derrence asked bluntly.

Tzadi looked at him. "Twenty thousand."

Derrence was startled. "Really? That's very high for a PR writer ... or even a company investigator."

Tzadi smiled. "You know what they say. No matter what you earn, you always need more."

"And you need more?"

"Yes. I have hidden expenses."

"Like what?"

Again Tzadi smiled. "Now, Der, you wouldn't believe me if I told you."

"Try me."

"Mental improvement. It costs me ten thousand a year and up to maintain the rate of growth I desire."

"You mean college courses and books and such things cost you ten thousand a year?"

"I said you wouldn't believe me."

"So you did," Derrence muttered.

"Shall we order?"

Derrence decided the time had come. "How much?" he asked quietly.

Tzadi was looking around the room. He turned to Derrence. "I beg your pardon?"

"How much do you want?"

Tzadi stared at him; then his head jerked slightly and he smiled and said, "Ah, yes. How much. For my silence. I see. That would be the way, wouldn't it?"

Derrence didn't understand the man's reaction. It was almost as if money had never entered Tzadi's head before this moment. But if it hadn't been money....

Tzadi said, "How much would you consider equitable?"

"You make almost twice as much as I do," Derrence said, some bitterness investing his voice. "Twenty a week should be enough to give you a few extra sessions in ... mental improvement."

"Agreed," Tzadi said.

Derrence covered his surprise, and his discomfort. This wasn't a man adept in the shakedown, the way a company spy should be. This was a man pleasantly surprised by a windfall!

"For that," Derrence said, "I expect absolute silence. You understand me, don't you?"

"Yes. I do. You can count on me, Der."

"Good," Derrence muttered, fighting the awful feeling that he'd thrown away a hefty slice of income for nothing. Yet Tzadi had information which could hurt him. Tzadi had known Mercy before today and lied about it. Tzadi had said he needed "help" with a personal problem.

They ordered. Tzadi ate lightly for a fat man; he left more than half his meal. As soon as he pushed away his plate, he said, "I wonder if you'd be kind enough to help me in another way, Der."

Derrence stopped chewing; then swallowed and took a sip of water. "Another way," he said flatly. So money hadn't been Tzadi's object.

"Yes. I ... uh...." For the first time, Tzadi showed uncertainty, even embarrassment. "Just as you're in trouble because of what I know, I'm in trouble because of what someone else knows. And actually, this someone else knows that I know about you."

"You mean you have to pay off...."

"No. She won't accept a bribe. Not money, not position, not anything. She wants me to ... turn you in."

Derrence stared at Tzadi. "Then what can I possibly do?"

Tzadi dropped his eyes. "Do away with her," he whispered.

They sat quietly for a good five minutes, Tzadi looking at the table, Derrence staring at Tzadi. Then Derrence said, "What does she know about you, Tzadi? I mean, what's the real reason you want her killed? You'll never make me believe it's just that she knows you know about me. You'd simply turn me in and the problem would be solved!"

Tzadi looked up. "I've told you the truth. I don't want to turn you in. She insists that I do. She's given me until next Monday—that's seven days, counting today. I have an office on the 41st floor. I moved down to 36 to meet you, personally; to decide whether I could turn you in. And I can't."

Derrence laughed.

Tzadi nodded. "I know it sounds ridiculous, but you represent something to me. Something unique and important and...." He stopped. He said, "We'll forget the twenty a week, though I desperately need extra money. If you will do away with Mercy Adrians...."

"Mercy? My secretary? She insists that you turn me in?"

"Yes. Do away with her and you can continue with your job, your life, as if nothing had happened. Let her live...." He shrugged.

Again Derrence laughed. "You assume my job means enough to me so that I'd kill for it?"

"I hope so," Tzadi whispered. "I fervently hope so."

"Well it doesn't," Derrence snapped, and looked around for the waiter.

Tzadi sighed. "Then there's nothing more to be said. I will give you as long as possible—until next Monday. Then I shall inform the proper people."

"Big deal," Derrence said, his heart sinking, his stomach twisting. "Better out of work than in the electric chair."

"Oh, but I can assure you of successfully escaping detection."

"You can," Derrence said, smiling thinly. He caught the waiter's eye. "And how can you do that?"

"I ... I can't tell you."

"I thought so. Why don't you do the job yourself, if you're so sure of getting away with it?"

"I am incapable of such things—just not built for ending life."

The waiter came. Derrence asked for the bill. The waiter glanced at the plates half full of food and asked if anything was wrong. Derrence said no, they were merely in a hurry. The waiter said, "But, sir, the management would be willing to give you credit for a meal if, indeed, the food were not absolutely...."

Tzadi said, "Will you stop this theatrical nonsense? Don't you know there's no audience left to appreciate it?"

The waiter looked at him. "Truly, sir?"

Tzadi hesitated; then said, "Except for one. Just one. And does it make sense to expect that one to come to this place of all the places in the world?"

The waiter's face was grim. "I ... I find it a very painful concept, sir. I know it was bound to happen, that it was the logical goal, and still...."

"Yes," Tzadi said. "Now please give us the bill."

The waiter wrote quickly and tore the sheet from his pad. He said, "That one, sir ... is he protected?"

"No," Tzadi said. "The majority say he must go."

"Well, they surely know what is best. But I...." He sighed and walked away.

"I too," Tzadi murmured. "I too."

"What was that all about?" Derrence asked. He was preoccupied with his own problem, but had heard enough to be puzzled. "You two sounded like a bad mystery movie; members of the underground meeting in enemy territory."

"Something like that," Tzadi said.

"One what?" Derrence asked. "You said there was only one. And what did he have to do with a waiter offering us credit on an unfinished meal? And why...."

"We are members of a rather strange religious order," Tzadi said, looking at Derrence with unblinking intensity. "The objects of our worship are just about extinct. Except for one. I recognized this waiter as practicing a certain ritual ... well, suffice it to say I told him we have run out of gods."

"Except for one?"

"Yes. One. Just one. And soon that one...."

"One what? Is it an animal?"

"Yes, an animal."

"How could he expect an animal to come to a restaurant?"

"As man is an animal."

"Then it's a man?"

"Yes, a man."

"To hell with this!" Derrence said, getting to his feet. "You're playing with me! I don't know why, but you're...."

Tzadi was also standing. "Please do not shout, Der." His eyes darted around the room. "No one here is shouting. You will be noted."

"Noted?" Derrence snorted. "Why the hell don't you learn to speak English! You may have me in the palm of your hand, but you don't speak well enough to be a clerk junior grade!"

"You are right. It is one of the reasons I need mental improvement."

Derrence reached for his wallet. Tzadi said, "Allow me, Der, please. I feel I have upset you and caused you to have a bad lunch."

Derrence had to laugh at that. He was confused, and through the confusion a strange new fear was growing, but still he had to laugh. "To put it mildly," he said, and walked away.

He returned to the office without waiting for Tzadi. Mercy was at her desk, typing one of his memos. She glanced up and smiled. "Nice lunch, Mr. Cale?"

He stopped. He looked at her; looked hard. "Yes."

She met his gaze, eyes puzzled.

What in the world could she have on Tzadi to make him want her dead?

"An interesting lunch, too, Mercy. I ate with your old friend, Edwin Tzadi."

She dropped her eyes. "My old friend? I met him today, as you did, Mr. Cale. Did he ... did he say different?"

"Yes, he said different."

Her head stayed down. "What ... what did he say?"

"He said you were his enemy, and my enemy." And he knew this was wrong. He was warning her, bringing the moment of his dismissal closer by seven days.

And then he understood why he was doing this. He didn't want seven days in which to consider killing Mercy Adrians. He was afraid of all that time. He was afraid he would learn that this job meant more to him than a young girl's life. "He said you wanted me turned in. He said that if he didn't turn me in, you would."

Her head came up, slowly, until she was looking at her typewriter. She began to type. He said, "Stop that and answer me."

She continued typing. Mr. Tzadi came up behind them, and passed them. He said, "Hello, Mercy, Der." Neither answered him. He stopped and looked at them. Mercy kept typing. He said, "I see you've made a serious error, Der." He said it softly, sadly.

He continued on up the hall. Derrence watched him. Tzadi said hello to everyone he passed. He called them by name. They called him by name. He knew everyone and everyone knew him.

The confusion was stronger, and so was the strange new fear. Everyone was a spy! Everyone on the 36th floor was in with Tzadi! And yet, Tzadi wanted him to stay on. It was Mercy, and the others, who wanted him fired. Yet how could everyone else....

He trembled. He backed from Mercy, staring at her. She kept typing. He turned and entered his office. He closed the door, and wished he could lock it. He heard himself saying, "Dear God, dear God, dear God." He sat behind his desk. Then he got up and went to the window. He looked down to the busy street far below. Cars and people; millions of them. Life, going on normally, as it always had. Why then this feeling of being alone? Why then this growing horror of total isolation?

"Except for one," Tzadi had said to the waiter, and the waiter's face had grown sad and he had moved away. As sad as Tzadi's face when he'd looked at Derrence in the hall a few minutes ago.

And the one was an animal. And man was an animal. And he was a man.

He shook his head and put his trembling hands together and said, "What is this? You're going to lose your job, granted. Is that any reason to lose your mind too? Tzadi and that waiter are religious nuts. They have a symbolism and language all their own. Besides...." Here he laughed, because the fear was coming out into the open, and as soon as it did it was revealed as ridiculous. "Besides, how can you be the last man on earth if Tzadi and all the others are here, right here in Chester Chemical? And the waiter and all the millions down there in the streets? And the other millions in the other cities and countries of the world?"

He sat down. He used his handkerchief to wipe sweat from his face and neck. He laughed, and it was almost his booming, confident laugh. He lit a cigarette and inhaled deeply. And then he began to tremble again. Against all logic, all reasoning, the horror of being totally alone in the world returned.

He got up and went to the door. He put his hand on the knob.

No, he couldn't open it!

He laughed. It was a cracked and shattered sound. He said, "Listen. Out there are the typists and writers and executives. Just listen to them. Just listen to the noise...." His voice slid upward in a strangled scream. He heard no noise.

He looked at his watch. Two-twenty. There had to be noise!

He put his ear to the door. Nothing. Not a sound of any sort.

He backed from the door, both hands over his mouth. He bumped into his desk. His phone rang. He listened to it. It rang and rang, the only sound on the 36th floor. Finally, he turned and picked it up. He heard Tzadi's voice. "Der, could you come to my office for a moment?"

He said, "What's happening?" He heard himself sobbing, and didn't care. He said, "Am I losing my mind? What's happening?"

"No, Der, you are not losing your mind." Tzadi's voice sounded as if he, too, were weeping. "It's just ... what I tried to tell you before."

"Yes, before. Listen, I've changed my mind. If it's the only way.... Listen, Ed, I'll do ... I'll do what you said. You know, Mercy. I'll...."

"Too late," Tzadi murmured. "Please come to my office, Der."

"No!"

"You must be dismissed, Der."

"Dismissed," Derrence said. "I must be dismissed." He quieted. "That's all that's going to happen, isn't it? I mean, I'm going to be fired?"

"Then you'll come to my office, Der?"

Derrence took a deep breath. "Yes."

The line clicked and went dead. Derrence put the phone down, carefully. He rubbed at his eyes, then wiped them with a handkerchief. "I'm going to be dismissed." It was a promise, a hope, now that the horror of something else, something insane and impossible, something infinitely worse filled his brain and chest and stomach. "I'm going to be dismissed."

He went to the door. He didn't stop to listen; just opened it. He stepped outside.

Mercy was at her desk, sitting quietly. She looked at him.

"It's all right, Mercy. I know. You were doing a job. It's all right."

His voice rang in the silence of the 36th floor. Mercy didn't answer. Mercy just looked at him.

He turned from her and walked up the hall. He passed Miss McCarty's office. He stopped, moved back, stood in her doorway. He would apologize for deceiving her.

She sat at her desk, looking at him. He said, "In a short while you'll learn I abused...."

His voice was a squeak in an empty cavern, a footfall on a dead planet. And Miss McCarty just looked at him, unblinking, unmoving.

He hurried up the hall, passing secretaries, writers, executives. All sat at their desks quietly; unblinking, unmoving. All looked at him.

He put his head down. He ran, and held back the screams rising in his throat. Tzadi would explain everything. Tzadi would laugh at his insane fears. Tzadi would fire him, and then he would ride down in the elevator and go home and have a drink.

He reached Tzadi's office. The door was open and Tzadi sat behind his desk, unblinking, unmoving. Behind him stood three men; taller, better built men than Tzadi. The middle one was looking out the window, his back to Derrence. The man to the right of Tzadi said, "Come in, please." He had a long, lean face. It looked sad.

Derrence moved forward, slowly, until he was right up against the desk. He looked down at Tzadi. "What's it all about, Ed?"

Tzadi said nothing.

"What did you try to do for me?"

The man to the right of Tzadi said, "He tried to save your life. He'll be dismantled for that. It's a sad thing, of course, him being one of the original hundred, but most have been dismantled anyway."

"Dismantled," Derrence said, the fear was immense now.

"You mean you don't know? You didn't guess anything, and Tzadi didn't tell you?"

Derrence raised his eyes from Tzadi. "Dismantled?"

"Yes. Taken apart. Destroyed. Killed. He lasted longer than most of the original hundred by each year. You understand? He was one of the first hundred made by the Original himself. That's why he had defects—stilted speech, squat construction and, most serious, a tendency to romanticize humanity. Even among the latest models, there are a few who feel that way, but once the last human is gone that problem...."

Derrence was calm now; the calmness beyond shock, beyond horror. "I'm the last human?"

"So we believe. There might be another in India—we're still checking. One more in Sweden is a possibility. But for the records, Derrence Cale was the last human being."

"Was the last human being," Derrence whispered.

The man to the left of Tzadi began to raise his right arm. The man to the right of Tzadi said, "Not yet." Then, more sharply, to Derrence, "We were kinder in our war than you and your people ever were. We created no blood baths, no gas chambers, no panic. Over a period of twenty-seven years, we eliminated and replaced. Families lived with our replacements, never suspecting the loved one was an android. We caused almost no pain at all, as you'll soon find out."

"Android," Derrence whispered. "Machine."

The voice grew curt. "Anything else you'd like to know?"

Derrence wanted to ask why Tzadi and the others were so quiet now, and why children still ran around the streets of residential neighborhoods, and—above all—what was the sense in a world of machines. But he asked no questions. These were not people. In man's image, but not man. Their answers weren't for him.

"I don't believe you," he said, wanting to hurt them, anger them; wanting most of all to hear himself say it. "I believe it's all a joke, or nightmare, or figment of my insane mind."

The man to Tzadi's right held up his hand. A small opening appeared in the palm, and grew larger. When it was a hole as large as the wrist behind it, the man said, "Breathe deeply and you won't suffer."

"Wait," the man to Tzadi's right said. "He's the last. Let him believe!" He tapped the man between; the one looking out the window with his back to Derrence. That man turned, and cleared his throat, and seemed embarrassed. Derrence heard himself laughing. It was too much. He looked at the man and laughed and laughed.

His duplicate, his android self, also laughed. It was the laugh of the true Derrence Cale—weak, frightened, ineffectual and apologetic. "I'm sorry, sir," the android Derrence Cale said. "I hope I can do as well as you've done."

The hand with the hole came across the desk, and something very sweet filled the air. Derrence Cale breathed deeply.

THE END