ON

DIGESTION

AND

DIETETICS.

By ANDREW COMBE, M. D.

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS IN EDINBURGH,

AND

CONSULTING PHYSICIAN TO THEIR MAJESTIES THE KING AND QUEEN

OF THE BELGIANS.

SECOND EDITION

REVISED AND ENLARGED.

“Nor is it left arbitrary, at the will and pleasure of every man, to do as he list; after the dictates of a depraved humour and extravagant phancy, to live at what rate he pleaseth; but every one is bound to observe the Injunctions and Law of Nature, upon the penalty of forfeiting their health, strength, and liberty,—the true and long enjoyment of themselves.”

Mainwayringe.

EDINBURGH:

MACLACHLAN & STEWART;

AND SIMPKIN, MARSHALL & CO. LONDON.

MDCCCXXXVI.

PRINTED BY NEILL & CO. OLD FISHMARKET.

[v]

ADVERTISEMENT

TO THE

SECOND EDITION.

The first edition of the present volume consisted of 2000 copies, and has been exhausted in little more than five months. Already, also, it has been twice reprinted in the United States. This success is extremely gratifying, and shews that the desire for information on the subject of the human constitution, is rapidly extending in proportion as it is discovered to be perfectly within the comprehension of every ordinary capacity, and to be directly and easily applicable to the farther improvement of the moral and physical condition of man.

The edition now offered to the public has been carefully revised, and about twenty pages of new matter have been added. Still, I fear, that many imperfections remain, which leisure and more confirmed[vi] health might have enabled me to remove, but which, under present circumstances, I feel compelled to leave to the good-natured indulgence of the reader.

It has been suggested by a professional critic for whose judgment I feel the utmost deference, that “the work would really have been more useful if the physiological or introductory part had been more condensed;” as much of it will, he thinks, be neither readily comprehended, nor usefully retained by the general reader.[1] My only reason for not acting on this suggestion is, that I regard the exposition of the laws of digestion of which that part consists, as the foundation on which all the dietetic rules contained in the second part must necessarily rest,—and am therefore extremely anxious that their nature and mode of operation should be thoroughly understood by the ordinary reader, even at the risk of too great minuteness. I am quite aware that the detail into which I have entered must appear tedious to every well educated practitioner; but as the book was intended more for the general than for the medical reader, the latter is evidently a less competent judge in this particular matter than the former. On referring, accordingly, to an unprofessional critic of no small ability and reputation, we find him of an entirely opposite opinion. For—“Of[vii] the two divisions of the book,” he thinks, “the FIRST is the most satisfactory and interesting, from the nature of its subject and the popular novelty of much of the information it imparts, or the force and freshness with which obvious truths are presented.”[2] And as other non-medical reviewers concur in this decision, I feel bound to attach more weight to them in what more especially concerns the class of readers to which they belong, and to retain the whole of the part objected to. In a purely medical question, on the other hand, I would as unhesitatingly have yielded to the judgment of the professional critic.

Edinburgh, 8 Alva Street,

November 1, 1836.

| Preface, | xvii |

| PART I. PHYSIOLOGY OF DIGESTION. |

|

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTORY REMARKS. |

|

| Waste or loss of substance always attendant on action—In the vegetable and animal kingdoms waste is greater than in the physical—Living bodies are distinguished by possessing the power of repairing waste—Vegetables, being rooted in one place, are always in connection with their food—Animals, being obliged to wander, receive their food at intervals into a stomach—Nutrition most active when growth and waste are greatest—In vegetables the same causes which increase these processes also stimulate nutrition—But animals require a monitor to warn them when food is needed—The sense of Appetite answers this purpose—The possession of a stomach implies a sense of Appetite to regulate the supplies of food, | 1–10 |

| CHAPTER II. THE APPETITES OF HUNGER AND THIRST. |

|

| Hunger and Thirst, what they are—Generally referred to the stomach and throat, but perceived by the brain—Proofs and illustrations—Exciting causes of hunger—Common theories unsatisfactory—Hunger sympathetic of the state of the body as well as of the stomach—Uses of appetite—Relation between waste and appetite—Its practical importance—Consequences of overlooking it illustrated by analogy of the whole animal kingdom—Disease from acting in opposition to this relation—Effect of exercise on appetite explained—Diseased appetite—Thirst—Seat of Thirst—Circumstances in which it is most felt—Extraordinary effects of injection of water into the veins in cholera—Uses of thirst, and rules for gratifying it, | 11–39 |

| CHAPTER III. MASTICATION, INSALIVATION, AND DEGLUTITION. |

|

| Mastication—The teeth—Teeth, being adapted to the kind of food, vary at different ages and in different animals—Teeth classed and described—Vitality of teeth and its advantages—Causes of disease in teeth—Means of protection—Insalivation and its uses—Gratification of taste in mastication—Deglutition, | 40–57 |

| CHAPTER IV. ORGANS OF DIGESTION—THE STOMACH—THE GASTRIC JUICE. |

|

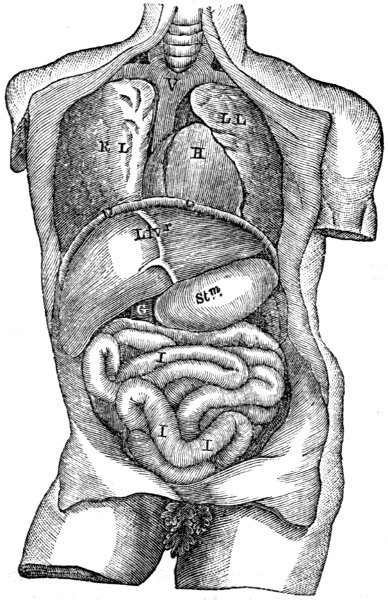

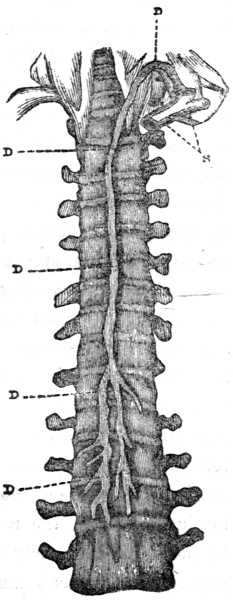

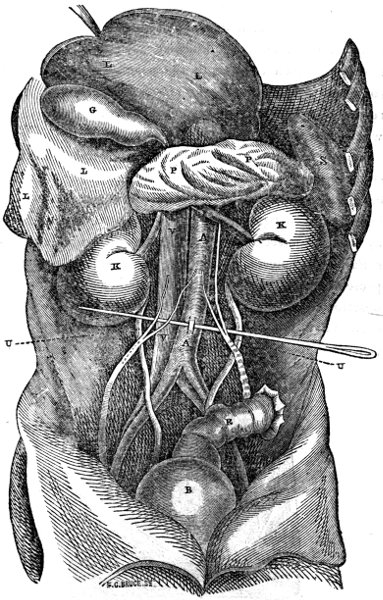

| Surprising power of digestion—Variety of sources of food—All structures, however different, formed from the same blood—General view of digestion, chymification, chylification, sanguification, nutrition—The stomach in polypes, in quadrupeds, and in man—Its position, size, and complexity, in different animals—Its structure; its peritoneal, muscular, and villous coats; and uses of each—Its nerves and bloodvessels; their nature, origins, and uses—The former the medium of communication between the brain and stomach—Their relation to undigested food—Animals not conscious of what goes on in the stomach—Advantages of this arrangement—The gastric juice the grand agent in digestion—Its origin and nature—Singular case of gunshot wound making a permanent opening into the stomach—Instructive experiments made by Dr Beaumont—Important results, | 58–108 |

| CHAPTER V. THEORY AND LAWS OF DIGESTION. |

|

| Different theories of Digestion—Concoction—Fermentation—Putrefaction—Trituration—Chemical solution—Conditions or laws of digestion—Influence of gastric juice.—Experiments illustrative of its solvent power—Its mode of action on different kinds of aliment—beef, milk, eggs, soups, &c.—Influence of temperature—Heat of about 100° essential to digestion.—Gentle and continued agitation necessary—Action of stomach in admitting food—Uses of its muscular motion—Gastric juice acts not only on the surface of the mass, but on every particle which it touches—Digestibility of different kinds of food—Table of results—Animal food most digestible—Farinaceous next—Vegetables and soups least digestible—Organs of digestion simple in proportion to concentration of nutriment—Digestibility depends on adaptation of food to gastric juice more than on analogy of composition—Illustrations.—No increase of temperature during digestion—Dr Beaumont’s summary of inferences, | 109–151 |

| CHAPTER VI. CHYLIFICATION, AND THE ORGANS CONCERNED IN IT. |

|

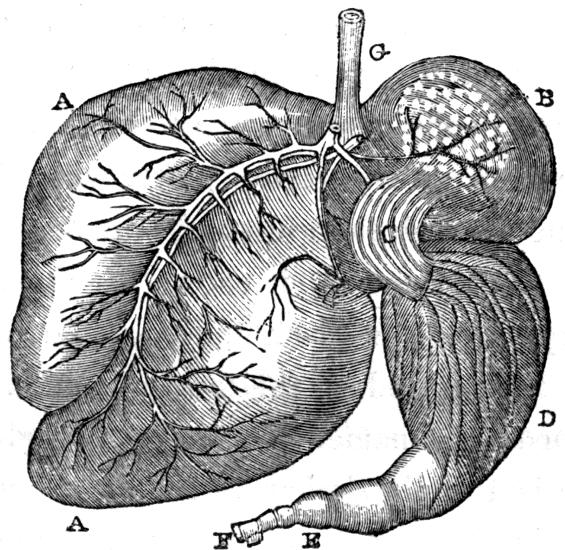

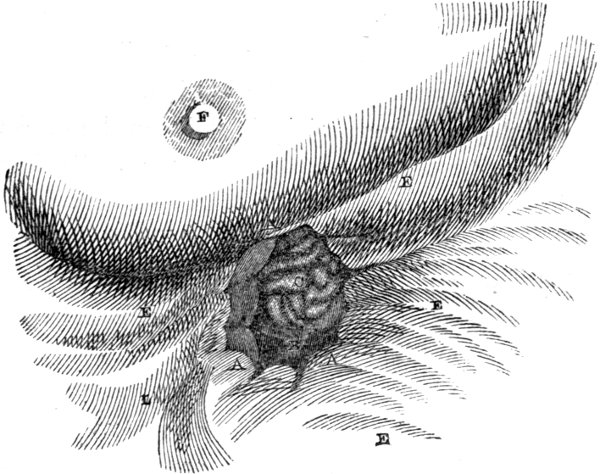

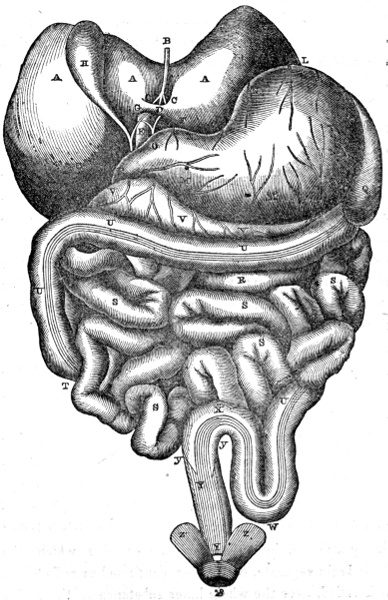

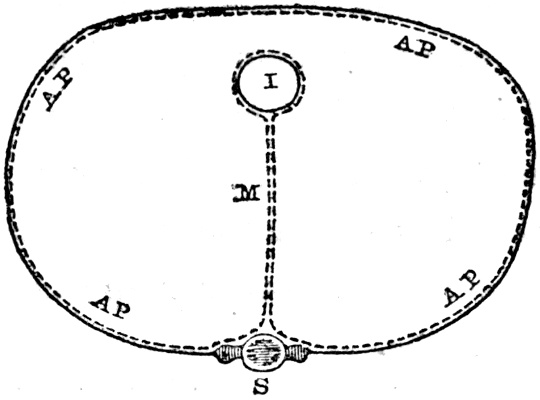

| Chylification—Not well known—Organs concerned in it—The intestinal canal—Its general structure—Peritoneal coat—Mesentery—Muscular coat—Uses of these—Air in intestines—Uses of—Mucous coat—Analogous to skin—The seat of excretion and absorption—Mucous glands—Absorbent vessels—Course of chyle towards the heart—Nerves of mucous coat—Action of bowels explained—Individual structure of intestines—The Duodenum—Jejunum—and Ileum—Liver and pancreas concerned in chylification—Their situation and uses—Bile, its origin and uses—The pancreas—Its juice—The jejunum described—The ileum—Cœcum—Colon—and Rectum—Peristaltic motion of bowels—Aids to it—Digestion of vegetables begins in stomach but often finished in the bowels—Illustration from the horse—Confirmation by Dupuytren, | 152–183 |

| PART II. THE PRINCIPLES OF DIETETICS VIEWED IN RELATION TO THE LAWS OF DIGESTION. |

|

| CHAPTER I. TIMES OF EATING. |

|

| The selection of food only one element in sound digestion—Other conditions essential—Times of eating—No stated hours for eating—Five or six hours of interval between meals generally sufficient—But must vary according to circumstances—Habit has much influence—Proper time for breakfast depends on constitution, health, and mode of life—Interval required between breakfast and dinner—Best time for dinner—Circumstances in which lunch is proper—Late dinners considered—Their propriety dependent on mode of life—Tea and coffee as a third meal, useful in certain circumstances—Supper considered—General rule as to meals—Nature admits of variety—illustrations—but requires the observance of principle in our rules, | 187–217 |

| CHAPTER II. ON THE PROPER QUANTITY OF FOOD. |

|

| Quantity to be proportioned to the wants of the system—Appetite indicates these—Cautions in trusting to appetite—General error in eating too much—Illustrations from Beaumont, Caldwell, Head, and Abercrombie—Mixtures of food hurtful chiefly as tempting to excess in quantity—Examples of disease from excess in servant-girls from the country, dressmakers, &c.—Mischief from excessive feeding in infancy—Rules for preventing this—Remarks on the consequences of excess in grown persons—Causes of confined bowels explained—And necessity of fulfilling the laws which God has appointed for the regulation of the animal economy inculcated, | 218–250 |

| CHAPTER III. OF THE KINDS OF FOOD. |

|

| What is the proper food of man?—Food to be adapted to constitution and circumstances—Diet must vary with time of life—Diet in infancy—The mother’s milk the best—Substitutes for it—Over-feeding a prevalent error—Causes which vitiate the quality of the milk—Regimen of nurses—Weaning—Diet after weaning—Too early use of animal food hurtful—Diet of children in the higher classes too exciting—and produces scrofula—Mild food best for children—Incessant eating very injurious—Proper diet from childhood to puberty—It ought to be full and nourishing but not stimulating—Often insufficient in boarding-schools—Diet best adapted for different constitutions in mature age—Regimen powerful in modifying the constitution, mental as well as physical—Farther investigation required, | 251–287 |

| CHAPTER IV. CONDITIONS TO BE OBSERVED BEFORE AND AFTER EATING. |

|

| General laws of organic activity apply to the stomach as well as to other parts—Increased flow of blood towards the stomach during digestion—Hence less circulating in other organs—and consequently less aptitude for exertion in them—Bodily rest and mental tranquillity essential to sound digestion—Rest always attended to before feeding horses—Hence also a natural aversion to exertion immediately after eating—Mischief done by hurrying away to business after meals—Severe thinking hurtful at that time—Playful cheerfulness after dinner conducive to digestion—The mind often the cause of indigestion—Its mode of operation explained—Also influences nutrition—Illustration from Shakspeare—Importance of attending to this condition of health enforced, | 288–303 |

| CHAPTER V. ON DRINKS. |

|

| Thirst the best guide in taking simple drinks—Thirst increased by diminution of the circulating fluids—The desire for liquids generally an indication of their propriety—Much fluid hurtful at meals—Most useful three or four hours later—The temperature of drinks is of consequence—Curious fall of temperature in the stomach from cold water—Ices hurtful after dinner—Useful in warm weather, when digestion is completed and caution used—Cold water more dangerous than ice when the body is overheated—Tepid drinks safest and most refreshing after perspiration—Kinds of drink—Water safe for every constitution—Wine, spirits, and other fermented liquors, too stimulating for general use, but beneficial in certain circumstances—Test of their utility, | 304–323 |

| CHAPTER VI. ON THE PROPER REGULATION OF THE BOWELS. |

|

| Functions of the intestines—The action of the bowels bears a natural relation to the kind of diet—Illustrations—And also to the other excretions—Practical conclusions from this—Different causes of inactivity of bowels—Natural aids to intestinal action—General neglect of them—Great importance of regularity of bowels—Bad health from their neglect—especially at the age of puberty—Natural means preferable to purgatives—Concluding remarks, | 324–339 |

| Index, | 341–350 |

[xvii]

The present volume is essentially a continuation of the work first published about two years ago, under the title of “The Principles of Physiology applied to the Preservation of Health and to the Improvement of Physical and Mental Education;” and its object is the same—namely, to lay before the public a plain and intelligible description of the structure and uses of some of the more important organs of the human body, and to shew how information of this kind may be usefully applied, not only in the prevention of suffering, but in improving the physical, moral, and intellectual condition of man.

In “The Principles of Physiology,” the structure and functions of the skin, muscles, bones, lungs, and nervous system, the laws or conditions of their healthy action, and the unsuspected origin of many of their diseases in infringements of these laws, were explained in succession at considerable length; and[xviii] the means by which their health and efficiency might best be secured were pointed out. It was stated that, in selecting these organs as subjects for discussion, I had been guided by the desire to notice in preference those functions which are most influential in their operation on the general system, and at the same time least familiarly known; and that, if the attempt to convey the requisite information in a manner suited to the general reader should prove successful, I would afterwards prepare a similar account of others, in the right understanding and management of which our interest is not less deeply involved, but in regard to which much ignorance continues nevertheless to prevail, even among the most liberally educated classes of society.

The numerous proofs which I received of the utility of my former work, not only from professional and literary journals, but also from individuals previously unknown to me,—many of them guardians and instructors of youth, speaking from personal experience,—together with the rapid sale of four large editions in little more than two years, soon completely satisfied me that I had neither been deceived as to the real importance of physiological knowledge to the general public, nor been altogether unsuccessful in the method of conveying it. Thus encouraged, accordingly, I cheerfully resumed my labours, and, from[xix] materials which had been long accumulating, began the preparation of the treatise now submitted to the indulgent consideration of the reader.

The matters discussed on the present occasion relate chiefly to the function of Digestion and the principles of Dietetics; and in selecting them I have been guided by the same principle as before. It may, at first sight, be doubted whether I have not exceeded proper bounds in thus dedicating a whole volume to the consideration of a single subject; but the more we consider the real complication of the function of Digestion,—the extensive influence which it exercises at every period of life over the whole of the bodily organization,—the degree to which its morbid derangements undermine health, happiness, and social usefulness,—and especially the share which they have in the production of scrofulous and consumptive as well as of nervous and mental affections,—we shall become more and more convinced of the deep practical interest which attaches to a minute acquaintance with the laws by which it is regulated. In infancy, errors in diet, and derangement of the digestive organs, are admitted to be among the principal causes of the striking mortality which occurs in that period of life. In youth and maturity, the same influence is recognised, not only in the numerous forms of disease directly traceable to that origin, but also in the universal[xx] practice of referring every obscure or anomalous disorder to derangement of the stomach or bowels. Hence, too, the interest which has always been felt by the public in the perusal of books on Dietetics and Indigestion; and hence the prevailing custom of using purgatives as remedies for every disorder, very often with good, but not unfrequently with most injurious effects.

Numerous and popular, however, as writings on Dietetics have been, and excellent as are many of the precepts which have been handed down by them from the earliest ages, sanctioned by the warm approval of every successive generation, it is singular how very trifling their influence has been, and continues to be, in altering the habits of those to whom they are addressed. In a general way, we all acknowledge that diet is a powerful agent in modifying the animal economy; yet, from our conduct, it might justly be inferred, that we either regarded it as totally devoid of influence, or remained in utter ignorance of its mode of operation, being left to the guidance of chance alone, or of notions picked up at random, often at variance with reason, and, it may be, in contradiction even with our own daily experience.

It has been alleged by a friendly critic of the first edition, that the author is too sanguine in expecting that the mere communication of knowledge will[xxi] suffice to alter the habits of the race, and that, although the information conveyed in the present volume may be turned to account by third parties—by mothers and nurses, for example—“yet with respect to the direct effect upon eaters,” slender results must be anticipated. “The world,” it is wittily added, “will read, admire, and applaud Dr Combe on Digestion and Dietetics, and then go on in its usual way eating what it likes, and digesting what it can.” The Author, however, never entertained the hope that his work would immediately produce the slightest perceptible change in the general practices of society, or that many healthy men of mature age and confirmed habits would forsake their accustomed regimen merely because it was shewn to be at variance with the laws of Nature. But as human conduct is in some measure influenced by knowledge, he is still confident enough to believe, that, among valetudinarians and the young of both sexes, whose habits are not formed, and numbers of whom err as much from ignorance as from the force of passion, many may be found who will be glad to obtain the guidance of knowledge and principle in the regulation of their mode of life; and that even many parents, who may not have resolution enough to forsake mischievous indulgences to which they have long been accustomed, may nevertheless be anxious to avail themselves[xxii] of any assistance on which they can depend for the better bringing up of their children. If in these expectations he is not too sanguine, the future advantage to the race from the present diffusion of dietetic knowledge is as certain, and almost as encouraging, as if its effects were instantaneous on both old and young. In the march of human improvement, months and years count but as moments. The men of to-day will soon have acted their part, and give place to those who are now with youthful energy adding to their knowledge, and throwing off a portion of the prejudices of their fathers. They in their turn will speedily be succeeded by their children, and the discoveries of the one generation will thus become the established and influential truths of the next. Each individual change in the habits of society may be so slow and minute as at the moment to escape our notice, but it is not on that account the less real. Nobody who compares the coarse feeding and riotous convivialities of our forefathers, at the beginning of last century, with the more refined and temperate habits of the present day, will think of denying that a prodigious step has been made in the interval even with respect to eating and drinking, which the critic seems to consider as so much beyond the influence of reason. And yet, if we take any single year of the whole century, we shall be unable to particularize any marked reformation which took[xxiii] place within its limits. This being the case, then, can we, their descendants, maintain that we are arrived so nearly at perfection as to leave no room for corresponding improvement in our day? My conviction is so much the reverse, that it seems to me certain that our onward progress will continue through generations yet unborn, with the same steadiness as it has done through generations long since gathered to their fathers; and that every attempt made to render man better acquainted with the laws of his own constitution, and thereby provide him with fixed and better principles of action, will exert a positive and decided influence on the progress of the race, proportioned in extent to the truth, clearness, and general applicability of the views which are unfolded. On such considerations do I ground my hope that the present volume, notwithstanding its numerous defects, will (in so far as it really embodies truths of practical importance) contribute in its own limited sphere to the general end.

The real cause of the little regard paid to dietetic rules—and it is of consequence to remark it—is not so much indifference to their influence, or even the absolute want of valuable information, as the faulty manner in which the subject is usually considered. In many of our best works, the relation subsisting between the human body on the one hand, and the qualities of alimentary substances on the other, is altogether[xxiv] lost sight of, although it is the only solid principle on which their proper adaptation to each other can be based. In this manner, while the attention is carefully directed to the consideration of the abstract qualities of the different kinds of aliment, little or no regard is paid to the relation in which they stand to the individual constitution, as modified by age, sex, season, and circumstances, or to the observance of the fundamental laws of digestion. And hence, although these conditions are not unfrequently of much greater importance to the general health than even the right selection of food, yet, when indigestion arises from neglecting them, the food alone is blamed, and erroneous conclusions are drawn, by relying on which, upon future occasions, we may easily be led into still more serious mistakes.

It is, indeed, from being left in this way without any guiding principle to direct their experience, and test the accuracy of the precepts laid down to them for the regulation of their conduct, that many persons begin by being bewildered by the numerous discrepancies which they meet with between facts and doctrine, between counsel and experience,—and end by becoming entirely sceptical on the subject of all dietetic rules whatever, and regarding them as mere theoretical effusions, based on fancy, and undeserving of a moment’s consideration.

The true remedy for this state of things is, not to[xxv] turn away in disgust and despair, but to resort to a more rational mode of inquiry—certain that, in proportion as we advance, some useful result will reward our labours. Such, accordingly, has been my aim in the present publication; and if I shall be found to have been even moderately successful in attaining it, I shall rejoice in the confident conviction that others will be led to still more positive and beneficial results. Utility has been my great object throughout. In following what I conceive to be an improved mode of investigation, I have in some instances placed known facts in a new point of view, and deduced from them practical inferences of considerable value and easy application: but beyond this, I lay no claim to originality; and if I have any where used expressions which may seem either to do injustice to others or to arrogate too much credit to myself, it has been entirely without any such design, and, consequently, I will be prompt to acknowledge my error and rectify the involuntary mistake.

In preparing the present volume for the press, I have derived the utmost advantage from a very valuable work by Dr Beaumont, an American writer, which—though faulty in its arrangement, and necessarily defective in many essential particulars—contains an authentic record of some of the most curious and instructive observations which have ever been[xxvi] made on the process of digestion. That excellent and enlightened physiologist had the rare good fortune to meet with a case where an artificial opening into the stomach existed, through which he could see every thing that took place during the progress of healthy digestion; and, with the most disinterested zeal and admirable perseverance, he proceeded to avail himself of the opportunity thus afforded of advancing human knowledge, by engaging the patient, at a heavy expense, to live with him for several years, and become the subject of numerous and carefully conducted experiments. Of the results thus obtained, I have not scrupled to make the freest and most ample use—not from considering them as positively new (for even Dr Beaumont lays little claim to the merit of a discoverer), but because they come before us so entirely freed from the numerous sources of error and doubt which formerly impaired their value, that they can now, for the first time, be safely trusted as practical guides in the science of dietetics. From Dr Beaumont’s work, also, being still inaccessible to the British reader, it is a bare act of justice towards him, and also the best way of fulfilling the objects he had in view, to make its contents known as widely as possible: for wherever they are known, they will be acknowledged to redound to his credit, not less as a man than as a philosopher.

[xxvii]

Objections have been stated to several of the repetitions which occur in the following pages. The only apology I have to offer for them is, that I committed them deliberately, because they seemed to me necessary to ensure clearness, and because the intimate manner in which the different functions are connected with each other, sometimes made it impossible to explain one without again referring to the rest. My prime objects being to render the meaning unequivocally plain, and impress the subject deeply upon the reader’s mind, I thought it better to risk in this way the occasional repetition of an important truth, than to leave it in danger of being vaguely apprehended, or its true value unperceived. For these reasons, it is hoped that the fault—if such it is—will be leniently overlooked.

Those who wish to study more fully the subject of Dietetics, will find much useful information in Dr Hodgkin’s “Lectures on the Means of Promoting and Preserving Health;” Professor Dunglison “On the Influence of Atmosphere and Locality, Change of Air and Climate, Seasons, Food, Clothing, Bathing, Exercise, Sleep, Corporeal and Intellectual Pursuits, &c. &c. &c. on Human Health;” Dr Paris “On Diet;” and Dr Kilgour’s “Lectures on the Ordinary Agents of Life, as applicable to Therapeutics and Hygiène.”

[1]

Waste or loss of substance always attendant on action.—In the vegetable and animal kingdoms waste is greater than in the physical.—Living bodies are distinguished by possessing the power of repairing waste.—Vegetables, being rooted in one place, are always in connexion with their food.—Animals, being obliged to wander, receive their food at intervals into a stomach.—Nutrition most active when growth and waste are greatest.—In vegetables the same causes which increase these processes also stimulate nutrition.—But animals require a monitor to warn then when food is needed.—The sense of Appetite answers this purpose.—The possession of a stomach implies a sense of Appetite to regulate the supplies of food.

Throughout every department of Nature waste is the invariable result of action. Even the minutest change in the relative position of inanimate objects cannot be effected without some loss of substance. So well is this understood, that it is an important aim in mechanics to discover the best means of reducing to the lowest possible degree the waste consequent upon motion. Entirely to prevent it is admitted to be beyond the power of man; for, however nicely parts may be adjusted to each other, however hard and durable their materials, and however smoothly motion may go on, still in the course of time loss of substance becomes evident, and repair and renewal[2] become indispensable to the continuance of the action.

It is thus a recognised fact, or general law of nature, that nothing can act or move without undergoing some change, however trifling in amount. Not even a breath of wind can pass along the surface of the earth without altering in some degree the proportions of the bodies with which it comes into contact; and not a drop of rain can fall upon a stone without carrying away some portion of its substance. The smoothest and most accurately formed wheel, running along the most level and polished railroad, parts with some portion of its substance at every revolution, and in process of time is worn out and requires to be replaced. The same effect is forcibly, though rather ludicrously, exemplified in the great toe of the bronze statue of St Peter at Rome, which in the course of centuries has been worn down to less than half its original size by the successive kisses of the faithful; and I venture to mention it, because it affords one of the best specimens of the operation of a principle, the existence of which, from the imperceptibly small effect of any single act, might otherwise be plausibly denied.

As regards dead or inanimate matter, the destructive influence of action is constantly forced upon our attention by every thing passing around us; and so much human ingenuity is exercised to counteract its effects, that no reflecting person will dispute the universality of its operation. But when we observe shrubs and trees waving in the wind, and animals undergoing violent exertion, for year after year, and yet both continuing to increase in size, we may be inclined, on a superficial view, to regard[3] living bodies as constituting exceptions to the rule. On more careful examination, however, it will appear that waste goes on in living bodies not only without any intermission, but with a rapidity immeasurably beyond that which occurs in inanimate objects. In the vegetable world, for instance, every leaf of a tree is incessantly pouring out some portion of its fluids, and every flower forming its own fruit and seed, speedily to be separated from and lost to its parent stem; thus causing in a few months an extent of waste many hundred times greater than what occurs in the same lapse of time after the tree is cut down, and all its living operations are at a close. The same thing holds true in the animal kingdom. So long as life continues, a copious exhalation from the skin, the lungs, the bowels, and the kidneys, goes on without a moment’s intermission; and not a movement can be performed which does not at least partially increase the velocity of the circulation, and add something to the general waste. In this way, during violent exertion several ounces of the fluids of the body are sometimes thrown out by perspiration in a very few minutes; whereas, after life is extinguished, all the excretions cease, and waste is limited to that which results from ordinary chemical decomposition.

So far, then, the law that waste is attendant on action, applies to both dead and living bodies; but beyond this point a remarkable difference between them presents itself. In the physical or inanimate world, what is once lost or worn away is lost for ever. There is no power inherent in the piston of the steam-engine by which it can repair its own loss of particles; and consequently in the[4] course of time it must either be laid aside as useless, or be remodelled by the hand of the workman. But living bodies, whether vegetable or animal, possess the distinguishing characteristic of being able to repair their own waste and add to their own substance. The possession of such a power is in fact essential to their very existence. If the sunflower, which in fine weather exhales thirty ounces of fluid between sunrise and sunset, contained no provision within its own structure for replacing this enormous waste, it would necessarily shrivel and die within a few hours, as it actually does when plucked up by the roots; and, in like manner, if man, whose system throws out every day five or six pounds of substance by the ordinary channels of excretion, possessed no means of repairing the loss, his organization would speedily decay and perish. This very result is frequently witnessed in cases of shipwreck and other disasters, where, owing to the impossibility of obtaining food, death ensues from the body wasting away till it becomes incapable of carrying on the operations of life. In some instances this waste has even proceeded so far that three-fourths of the whole weight of the body have been lost before life became extinct.

It is impossible to reflect on these facts, and others of a similar kind, without having the conviction forced upon our minds, that in every department of nature expenditure of material is inseparable from action, and that, in living bodies, waste goes on so rapidly, and by so many different channels, that life could not be maintained for any length of time without an express provision being made for compensating its occurrence.

[5]

In surveying the respective modes of existence of vegetables and of animals, with the view of ascertaining by what means this compensation is effected, the first striking difference between them which we perceive, is the fixity of position of the one, and the free locomotive power of the other. The vegetable grows, flourishes, and dies, fixed to the same spot of earth from which it sprang; and, however much external circumstances may change around it, it must remain and submit to their influence. If it be deprived of moisture and solar heat and light, it cannot go in search of them, but must remain to droop and to perish. If the earth to which its roots are attached be removed, and a richer soil be substituted than that which its nature requires, it still has no option: it must grow up in rank and unhealthy luxuriance, in obedience to an impulse which it cannot resist. At all hours and at all seasons it is at home, and in direct communication with the soil from which its nourishment is extracted. And being thus without ceasing in contact with its food, it requires no storehouse in which to lay up provision, but receives immediately from the earth, and at every moment, all that is necessary for its sustenance.

But it is otherwise with animals. These not only enjoy the privilege of locomotion, but are compelled to use it, and often to go to a distance, in search of food and shelter. Consequently, if their vessels of nutrition were like those of vegetables in direct communication with external substances, they would be torn asunder at every movement, and the animals themselves exposed either to die from starvation, or to forego the exercise of the[6] higher functions for which their nature is adapted. But the necessity for a constant change of place being imposed on them, a different arrangement became indispensable for their nutrition: and the method by which the Creator has remedied the inconvenience is not less admirable than simple. To enable the animal to move about and at the same time to maintain a connexion with its food, He has provided it with a receptacle or stomach, where it is able to store up a supply of materials from which sustenance may be gradually elaborated during a period of time proportioned to its necessities and mode of life. It thus carries along with it nourishment adequate to its wants; and the small nutritive vessels imbibe their food from the internal surface of the stomach and bowels, where the nutriment is stored up, just as the roots or nutritive vessels of vegetables do from the soil in which they grow. The possession of a stomach or receptacle for food is accordingly a characteristic of the animal system as contrasted with that of vegetables; it is found even in the lowest orders of zoophytes, which in other respects are so nearly allied to plants.

The sole objects of nutrition being to repair waste and to admit of growth, Nature has so arranged that within certain limits it is always most vigorous when growth or waste proceeds with the greatest rapidity. Even in vegetables this relation is distinctly observable. In spring and summer, when vegetative life is most active, and when leaves, flowers, and fruit, are to be formed, and growth carried on, nourishment is largely drawn from the soil, and the elaboration and circulation of the sap are proportionally vigorous; whereas in winter, when the leaves and flowers[7] have passed away, and vegetable life is in repose, little nourishment is needed, and the circulation of the sap is proportionally slow. In accordance with these facts, every one will recollect how freely a shrub or a tree bleeds, as it is called, when its bark is cut early in the season, and how dry it becomes on the approach of winter. It is the activity of the circulation in summer which renders its temporary suspension by transplanting so generally fatal at that season; whereas, owing to the comparative sluggishness with which it is carried on in winter, its partial interruption is then attended with much less risk.

In vegetables, the quantity of nourishment taken in entirely depends on, and is regulated by, the circumstances in which they are placed. When they are exposed, as in spring and summer, to the stimulus of heat and light, all their functions are excited, waste and growth are accelerated, and a more abundant supply of nourishment becomes indispensable to their health and existence; and hence, in a dry soil incapable of affording a copious supply of sap, they speedily wither and die. Exposed to cold, on the other hand, and shaded from the light, their vitality is impaired, and the demand for nourishment greatly diminished. This is uniformly the case in winter; and many circumstances shew that the change is really owing to the causes mentioned above, and not to any thing inherent in the constitution of the vegetable itself. In tropical climates, for example, where heat, light, and moisture abound, vegetable life is ever active, and the foliage ever thick and abundant; and even in our own northern region, we are able by artificial heat so far[8] to anticipate the natural order of the seasons, as to obtain the ripened fruit of the vine in the very beginning of spring. The whole system of forcing vegetables and fruit, so generally resorted to for the early supply of our markets, is, in truth, founded on the principle we are now discussing; and by the regulated application of heat, light, and moisture, we are able to hasten or to retard, to a very considerable extent, the ordinary stages of vegetable life. But to ensure success in our operations, we must be careful to proportion the supply of nourishment to the state of the plant at the time. If, by the application of heat, we have stimulated it to premature growth and foliage, we must at the same time provide for it an adequate supply of food, otherwise its activity will exhaust itself, and induce premature decay. Hence the regular watering which greenhouse plants require. But if we have retarded its progress and lowered its vitality by excluding heat and light, the same copious nourishment will not only be unnecessary, but will probably do harm by inducing repletion and disease.

In vegetables, the absorption of food is thus regulated chiefly by the circumstances of heat, moisture, and light, under which the plant is placed, and by the consequent necessity which exists at the time for a larger or smaller supply of nourishment to carry on the various processes of vegetable life. According to this arrangement, nutrition is always most active when the greatest expenditure of material is taking place. When growth is going on rapidly, and the leaves are unfolding themselves, sap is sucked up from the earth in immense quantity; but when these processes are completed as summer advances, and[9] almost no fresh materials are required, except for the consolidation of the new growth and the supply of the loss by exhalation, a much smaller amount of nourishment suffices, and the sap no longer circulates in the same profusion. In autumn, again—when the fruit arrives at maturity, the leaves begin to drop off, and the activity of vegetable life suffers abatement—nutrition is reduced to its lowest ebb; and in this state it continues till the return of spring stimulates every organ to new action, and once more excites a demand for an increased supply.

Nor is the same great principle, of supply requiring to be proportioned to demand, less strikingly apparent in animals. Wherever growth is proceeding rapidly, or the animal is undergoing much exertion and expenditure of material, an increased quantity of food is invariably required; and, on the other hand, where no new substance is forming, and where, from bodily inactivity, little loss is sustained, a comparatively small supply will suffice. But as animals are subjected to much more rapid and violent transitions from activity to inactivity than vegetables are—and thus require to pass more immediately from one kind and quantity of nourishment to another, in order to adapt their nutrition to the ever-varying demands made upon the system—they evidently stand in need of some provision to enforce attention when nourishment is necessary, and to enable them always to proportion the supply to the real wants of the body. Not being, like vegetables, in constant connection with their aliment, they might suffer from neglect if they did not possess some contrivance to warn them in time when to seek[10] and in what quantity to consume it. But in endowing animals with the sense of Appetite, or the sensations of Hunger and Thirst generally included under it, the Creator has guarded effectually against the inconvenience, and given to them a guide in every way sufficient for the purpose.

The very possession of a stomach or receptacle, into which food sufficient for a shorter or longer period can be introduced at one time, and which we have already remarked as characterizing all animals from the lowest to the highest, almost necessarily implies the co-existence of some watchful monitor, such as appetite, to enforce attention to the wants of the system, with an earnestness which it shall not be easy to resist. If this were not the case in man, for example—if he had no motive more imperative than reason to oblige him to take food—he would be constantly liable, from indolence and thoughtlessness, or the pressure of other occupations, to incur the penalty of starvation, without being previously aware of his danger. But the Creator, with that beneficence which distinguishes all His works, has not only provided an effectual safeguard in the sensations of hunger and thirst, but moreover, attached to their regulated indulgence a degree of pleasure which never fails to insure attention to their demands, and which, in highly civilized communities, is apt to lead to excessive gratification. Such being the important charge committed to the appetites of hunger and thirst, it will be proper to submit to the reader, before entering upon the consideration of the more complicated process of digestion, a few remarks on their nature and uses.

[11]

Hunger and Thirst, what they are—Generally referred to the stomach and throat, but perceived by the brain—Proofs and illustrations—Exciting causes of hunger—Common theories unsatisfactory—Hunger sympathetic of the state of the body as well as of the stomach—Uses of appetite—Relation between waste and appetite—Its practical importance—Consequences of overlooking it illustrated by analogy of the whole animal kingdom—Disease from acting in opposition to this relation—Effect of exercise on appetite explained—Diseased appetite—Thirst—Seat of Thirst—Circumstances in which it is most felt—Extraordinary effects of injection of water into the veins in cholera—Uses of thirst, and rules for gratifying it.

In the preceding chapter, I endeavoured to shew, first, that nutrition is required only because waste, and a deposition of new particles, are continually going on, so that the body would speedily become exhausted if its constituent materials were not renewed; secondly, that the sense of appetite is given to animals for the express purpose of warning them when a fresh supply of aliment is needed—as, without some such monitor, they would be apt to neglect the demands of nature; and thirdly, that vegetables have no corresponding sensation, simply because, from their being at all times in communication with the soil, their nutrition goes on continuously in proportion as it is[12] necessary, and without requiring any prompter to put it in action at particular times.

If these principles be correct, it follows that, in the healthy state (and let the reader be once for all made aware that in the following pages the state of health is always implied, except where it is otherwise plainly expressed), the dictates of appetite will not be every day the same, but will vary according to the mode of life and wants of the system, and, when fairly consulted, will be sufficient to direct us both at what time and in what quantity we ought to take in either solid or liquid sustenance. But to make this perfectly evident, a few general observations may be required.

It is needless to waste words in attempting to describe what hunger and thirst are: every one has felt them, and no one could understand them without such experience, any more than sweetness or sourness could be understood without tasting sweet or sour objects. Their end is manifestly to proclaim that farther nourishment is required for the support of the system; and our first business is, therefore, to explain their nature and seat, in so far at least as a knowledge of these may be conducive to our welfare.

The sensation of hunger is commonly referred to the stomach, and that of thirst to the upper part of the throat and back of the mouth; and correctly enough to this extent, that a certain condition of the stomach and throat tends to produce them. But, in reality, the sensations themselves, like all other mental affections and emotions, have their seat in the brain, to which a sense of the condition of the stomach is conveyed through the medium of[13] the nerves. In this respect, Appetite resembles the senses of Seeing, Hearing, and Feeling; and no greater difficulty attends the explanation of the one than of the others. Thus, the cause which excites the sensation of colour, is certain rays of light striking upon the nerve of the eye; and the cause which excites the perception of sound, is the atmospherical vibrations striking upon the nerve of the ear; but the sensations themselves take place in the brain, to which, as the organ of the mind, the respective impressions are conveyed. In like manner, the cause which excites appetite is an impression made on the nerves of the stomach; but the feeling itself is experienced in the brain, to which that impression is conveyed. Accordingly, just as in health no sound is ever heard except when the external vibrating atmosphere has actually impressed the ear, and no colour is perceived unless an object be presented to the eye,—so is appetite never felt, except where, from want of food, the stomach is in that state which forms the proper stimulus to its nerves, and where the communication between it and the brain is left free and unobstructed.

But as, in certain morbid states of the brain and nerves, voices and sounds are heard, or colours and objects are seen, when no external cause is present to act upon the ear or the eye,—so, in disease, a craving is often felt when no real want of food exists, and where, consequently, indulgence in eating can be productive of nothing but mischief. Such an aberration is common in nervous and mental diseases, and not unfrequently adds greatly to their severity and obstinacy. In indolent unemployed persons, who spend their days in meditating on their own[14] feelings, this craving is very common, and from being regarded and indulged as if it were healthy appetite, is productive of many dyspeptic affections.[3]

If the correctness of the preceding explanation of the sensation of hunger be thought to stand in need of confirmation, I would refer to the very conclusive experiments by Brachet of Lyons, as setting the question entirely at rest. Brachet starved a dog for twenty-four hours, till it became ravenously hungry, after which he divided the nerves which convey to the brain a sense of the condition of the stomach. He then placed food within its reach, but the animal, which a moment before was impatient to be fed, went and lay quietly down, as if hunger had never been experienced. When meat was brought close to it, it began to eat; and, apparently from having no longer any consciousness of the state of its stomach—whether it was full or empty—it continued to eat till both it and the gullet were inordinately distended. In this, however, the dog was evidently impelled solely by the gratification of the sense of taste; for on removing the food at the beginning of the experiment to the distance of even a few inches, it looked on with indifference, and made no attempt either to follow the dish or to prevent its removal.[4]

Precisely similar results ensued when the nervous sympathy between the stomach and brain was arrested by the administration of narcotics. A dog suffering[15] from hunger turned listlessly from its food when a few grains of opium were introduced into its stomach. It may be said that such a result is owing to the drug being absorbed and carried to the brain through the ordinary medium of the circulation; but Brachet has proved that this is not the case, and that the influence is primarily exerted upon the nerves. To establish this point, two dogs of the same size were selected. In one the nerves of communication were left untouched, and in the other they were divided. Six grains of opium were then given to each at the same moment. The sound dog began immediately to feel the effects of the opium and became stupid, while the other continued lying at the fireside for a long time, without any unusual appearance except a little difficulty of breathing. In like manner, when the experiment was repeated with that powerful poison nux vomica, upon two dogs similarly circumstanced, the sound one fell instantly into convulsions, while the other continued for a long time as if nothing had happened.

These results demonstrate, beyond the possibility of doubt, the necessity of a free nervous communication between the stomach and brain, for enabling us to experience the sensation of hunger. The connexion between the two organs is indeed more widely recognised in practice than it is in theory; for it is a very common custom with the Turks to use opium for abating the pangs of hunger when food is not to be had, and sailors habitually use tobacco for the same purpose. Both substances act exclusively on the nervous system.

The relation thus shewn to subsist between the stomach and the brain, enables us in some measure to understand[16] the influence which strong mental emotions and earnest intellectual occupation exert over the appetite. A man in perfect health, sitting down to table with an excellent appetite, receives a letter announcing an unexpected calamity, and instantly turns away with loathing from the food which, a moment before, he was prepared to eat with relish; while another, who, under the fear of some misfortune, comes to table indifferent about food, will eat with great zest on his “mind being relieved,” as the phrase goes, by the receipt of pleasing intelligence. Excessive and absorbing emotion, even of a joyful kind, has the same effect. Captain Back tells us in the interesting narrative of his last journey, that when he first heard of Captain Ross’s return, “the thought of so wonderful a preservation overpowered, for a time, the common occurrences of life. We had but just sat down to breakfast, but our appetite was gone, and the day passed in a feverish state of excitement,” (P. 245). In such cases, no one will imagine that the external cause destroys appetite otherwise than through the medium of the brain. Occasionally, indeed, the aversion to food amounts to a feeling of loathing and disgust, and even induces sickness and vomiting,—a result which depends so entirely on the state of the brain, that it is often excited by mechanical injuries of that organ.

The analogy between the external senses and the appetite is in various respects very close. If we are wrapt in study, or intent on any scheme, we become insensible to impressions made on the ear or eye. A clock may strike, or a person enter the room, without our being aware of either event. The same is the case with the[17] desire for food. If the mind is deeply engaged, the wants of the system are unperceived and unattended to—as was well exemplified in the instance of Sir Isaac Newton, who, from seeing the bones of a chicken lying before him, fancied that he had already dined, whereas, in reality, he had eaten nothing for many hours. Herodotus ascribes so much efficacy to mental occupation in deadening the sense of hunger, that he speaks of the inhabitants of Lydia having successfully had recourse to gaming as a partial substitute for food, during a famine of many years continuance. In this account there is, of course, gross exaggeration; but it illustrates sufficiently well the principle under discussion.

Many attempts have been made but without much success, to determine what the peculiar condition of the stomach is which excites in the mind the sensation of hunger. For a long time it was imagined that the presence of gastric or stomach juice, irritating the nerves of the mucous membrane, was the exciting cause; but it was at last ascertained, that, after the digestion of a meal is completed, and the chyme has passed into the intestine, the gastric juice ceases to be secreted till after a fresh supply of food has been taken in.[5] It was next supposed that the mere emptiness of the stomach was sufficient[18] to excite hunger, and that the sensation arose partly from the opposite sides rubbing against each other. But this theory is equally untenable; for the stomach generally contains a sufficient quantity of air to prevent the actual contact of its sides, and moreover it may be entirely void of food and yet no appetite be felt. It may be laid down, indeed, as a general rule, that an interval of rest must follow the termination of digestion before the stomach becomes fit to resume its functions, or appetite is experienced in any degree of intensity; and the length of time required for this purpose varies very much, according to the mode of life and to the extent of waste going on in the system. In many diseases, too, the stomach remains empty for days in succession, without any corresponding excitation of hunger. Even in healthy sedentary people, whose expenditure of bodily substance is small, real appetite is not felt till long after the stomach is empty, and hence one of their most common complaints is the want of appetite.

Dr Beaumont suggests a distended state of the vessels which secrete the gastric juice as the exciting cause of hunger, and thinks that this view is strengthened by the rapidity with which the juice is poured out after a short fast—a rapidity, he says, which cannot be accounted for except by supposing the juice to have existed ready made in the vessels or follicles by which it is secreted. But this theory is not more satisfactory than the rest, for in the sudden flow of saliva into the mouth of a hungry man on the unexpected appearance of savoury viands, we have an instance of equally rapid secretion where there was evidently no storing up beforehand, Besides, there is[19] an obvious relation between appetite and the wants of the system, which is not always taken sufficiently into account, and which is nevertheless too important to be overlooked.

If the body be very actively exercised, and a good deal of waste be effected by perspiration and exhalation from the lungs, the appetite becomes keener, and more urgent for immediate gratification; and if it is indulged, we eat with a relish unknown on other occasions, and afterwards experience a sensation of bien-être or internal comfort pervading the frame, as if every individual part of the body were imbued with a feeling of contentment and satisfaction, the very opposite of the restless discomfort and depression which come upon us, and extend over the whole system, when appetite is disappointed. An amusing example of the principle here inculcated is to be found in the Correspondance Inedite de Madame du Deffand,[6] where she describes her friend Madame de Pequigni as an insatiable bustling little woman who consumes two hours every day in devouring her dinner, and “eats like a wolf.” But, then, remarks Madame du Deffand by way of explanation, “Il est vrai qu’elle fait un exercice enragé.”

There is, in short, an obvious and active sympathy between the condition and bearing of the stomach and those of every part of the animal frame—in virtue of which, hunger is felt very keenly when the general system stands in urgent need of repair, and very moderately when no waste has been suffered. This principle is strikingly illustrated during recovery from a severe illness. “In convalescence from an acute disease,” as is[20] well remarked by Brachet, “the stomach digests vigorously, and yet the individual is always hungry. This happens because all the wasted organs and tissues demand the means of repair, and demand them from the stomach, which has the charge of sending them; and, therefore, they keep up in it the continual sensation of want, which, however, is, in this case, only sympathetic of the state of the body.”[7] In alluding to this subject, Blaine observes, that “Hunger and thirst can only be satisfactorily explained by considering them as properties in the stomach by which it sympathizes with the wants of the constitution; and hence it is, that food taken in invigorates, even before it can be digested.”[8] Hence also the prostration of strength that is felt when the stomach has been for some time empty.

This sympathy is sometimes singularly manifest even in disease. In some cases of affection of the mesenteric glands, for example, where stomachic digestion remains for a time pretty healthy, and the general system suffers chiefly from the want of nourishment caused by the passage of the chyle into the blood being obstructed, the appetite continues as keen and often keener than before; because the system, being in want of nourishment, and the stomach healthy, all its natural causes continue to act as before; and accordingly, when food is taken, it is digested there as usual, but the chyle which is formed from it in the intestine can no longer be transmitted through the swollen glands in its usual healthy manner, to be converted[21] into nutritive blood in the lungs; and the system thus failing to receive the required supply, recommences its cravings almost as soon as if no food had been obtained. When the disease has advanced a certain length, however, fever springs up, and destroys both appetite and digestion.

The effects of exercise, also, shew very clearly the connexion between appetite and the state of the system. If we merely saunter out for a given time every day, without being actively enough engaged to quicken the circulation and induce increased exhalation from the skin and lungs, we come in with scarcely any change of feeling or condition; whereas, if we exert ourselves sufficiently to give a general impetus to the circulation, and bring out moderate perspiration, but without inducing fatigue, we feel a lightness and energy of a very pleasurable description, and generally accompanied by a strong desire for food. Hence the keen relish with which the fox-hunter sits down to table after a successful chase.

This intimate communion between the state of the system and that of the stomach is a beautiful provision of Nature, and is one of the causes of the ready sympathy which has often been remarked as existing between the stomach and all the other organs—in other words, of the readiness with which they accompany it in its departure from health, and the corresponding aptitude of their disorders to produce derangement of the digestive function. Apparently for the purpose, among others, of thus intimately connecting the stomach with the rest of the system, it is supplied with a profusion of nervous filaments[22] of every kind, which form a closely-interwoven nervous network in its immediate neighbourhood, and the abundance of which accounts for the severe and often suddenly fatal result of a heavy blow on the pit of the stomach.

Without pretending to determine what the precise condition of the nerves of the stomach is, which, when conveyed to the brain, excites the sensation of appetite, I think it sufficient for every practical purpose if we keep in mind, that the co-operation of the nervous system is necessary for the production of appetite, and that there is a direct sympathy between the stomach and the rest of the body, by means of which the stimulus of hunger becomes unusually urgent where the bodily waste has been great, although a comparatively short time has elapsed since the preceding meal.

Appetite, then, being given for the express purpose of warning as when a supply of food is necessary, it follows that its call will be experienced in the highest intensity when waste and growth—or, in other words, the operations which demand supplies of fresh materials—are most active; and in the lowest intensity when, from indolence and the cessation of growth, the demand is least. In youth, accordingly, when bodily activity is very great, and a liberal supply of nourishment is required both to repair waste and to carry on growth, the appetite is keener and less discriminating than at any other period of life, and, what is worthy of remark, as another admirable instance of adaptation, digestion is proportionally vigorous and rapid, and abstinence is borne with great difficulty; whereas, in mature age, when growth is finished and the[23] mode of life more sedentary, the same abundance of aliment is no longer needed, the appetite becomes less keen and more select in its choice, and digestion loses something of the resistless power which generally distinguishes it in early youth. Articles of food which were once digested with ease are now burdensome to the stomach, and, if not altogether rejected, are disposed of with a degree of labour and difficulty that was formerly unknown. Abstinence also is now more easily supported.

When, however, the mode of life in mature age is active and laborious, and the waste matter thrown out of the system is consequently considerable, the appetite for food and the power of digesting it are correspondingly strong; for in general it is only when the mode of life is indolent and inactive, and the waste consequently small, that the appetite and digestion are weak. So natural, indeed, is the connexion between the two conditions, that exercise is proverbially the first thing we think of recommending to improve the appetite and the tone of the digestive organs, when these are observed to be impaired; and where positive disease does not exist, no other remedy is half so effectual. But, as already noticed, exercise to be beneficial must be of a description calculated to increase the activity of the secretions and excretions; otherwise it cannot place the system in a condition to require an abundant supply or excite vigorous digestion.

It is highly important to notice this natural relation between waste and appetite, and between appetite and digestion; because, if it be real, appetite must be the safest guide we can follow in determining when and how much we ought to eat. It is true that in disease, and[24] amidst the factitious calls and wants of civilized life, its suggestions are often perverted, and that hence we may err in blindly following every thing which assumes its semblance. The conclusion to be drawn from this, however, is, not that the sense of hunger will, if trusted to, generally mislead us, but only that we must learn to distinguish its true dictates before we can implicitly rely on its guidance. If, when fairly consulted, its dictates are found to be erroneous, it will constitute the only known instance where the Creator has failed in the attempt to fulfil his own design—an assumption not only repugnant alike to feeling and to reason, but in fact altogether gratuitous. For the apparent discrepancies which occasionally present themselves between the wants of the system and the dictates of appetite, are easily explicable on the more solid ground of our own ignorance and inattention.

Many practical errors arise from overlooking the relation which nutrition ought to bear to waste and growth. Thus, it is no uncommon thing for young men who have experienced all the pleasures of a keen appetite and easy digestion when growing rapidly or leading an active life, to induce severe and protracted indigestion, by continuing, from mere habit, to eat an equal quantity of food either when growth is finished and the system no longer requires the same extensive supply, or after a complete change from active to sedentary habits has greatly diminished that waste which alone renders food necessary. This is, in fact, one of the chief sources of the troublesome dyspeptic complaints often met with among the youthful inhabitants of our larger cities and colleges, and ought not to be lost sight of in the physical education of the young.

[25]

The error, however, is unhappily not confined to the young, but extends generally to all whose pursuits are of a sedentary nature. There are numerous persons, especially in towns and among females, who, having their time and employments entirely at their own disposal, carefully avoid every thing which requires an effort of mind or body, and pass their lives in a state of inaction entirely incompatible with the healthy performance of the various animal functions. Having no bodily exertion to excite waste, promote circulation, or stimulate nutrition, they experience little keenness of appetite, have weak powers of digestion, and require but a limited supply of food. If, while inactive and expending little, such persons could be contented to follow nature so far as not to provoke appetite by stimulants and cookery, and to eat and drink only in proportion to the wants of the system, they would fare comparatively well. But having no imperative occupation and no enjoyment from active and useful exertion, their time hangs heavily on their hands, and they are apt to have recourse to eating as the only avenue to pleasure still open to them; and, forgetful or ignorant of the relation subsisting between waste and nutrition, they endeavour to renew, in the present indulgence of appetite, the real enjoyment which its legitimate gratification afforded under different circumstances. Pursuing the pleasures of the table with the same ardour as before, they eat and drink freely and abundantly, and, instead of trying to acquire a healthy desire for food and increased powers of digestion by exercise, they resort to tonics, spices, wine, and other stimuli, which certainly excite for the moment, but eventually aggravate the mischief by[26] obscuring its progress and extent. The natural result of this mode of proceeding is, that the stomach becomes oppressed by excess of exertion—healthy appetite gives way, and morbid craving takes its place—sickness, head-ach, and bilious attacks, become frequent—the bowels are habitually disordered, the feet cold, and the circulation irregular—and a state of bodily weakness and mental irritability is induced, which constitutes a heavy penalty for the previous indulgence. So far, however, is the true cause of all these phenomena from being perceived even then, that a cure is sought, not in a better regulated diet and regimen, but from bitters to strengthen the stomach, laxatives to carry off the redundant materials from the system, wine to overcome the sense of sinking, and heavy lunches to satisfy the morbid craving which they only silence for a little. Some, of course, suffer in a greater and others in a less degree, according to peculiarities of constitution, mode of life, and extent of indulgence; but daily experience will testify, that, in its main features, the foregoing description is not over-charged, and that victims to such dietetic errors are to be met with in every class of society.

The fact of Nature having meant the inactive and indolent to eat and drink less than the busy and laborious, is established not only by the diminished appetite and impaired digestion of human beings who lead a sedentary life, as contrasted with the keen relish and rapid digestion usually attendant on active exertion in the open air, but on a yet broader scale by the analogy of all other animals. In noticing this relation, Dr Roget remarks that “the greater the energy with which[27] the more peculiarly animal functions of sensation and muscular action are exercised, the greater must be the demand for nourishment, in order to supply the expenditure of vital force created by these exertions. Compared with the torpid and sluggish reptile, the active and vivacious bird or quadruped requires and consumes a much larger quantity of nutriment. The tortoise, the turtle, the toad, the frog, and the chameleon, will indeed live for months without taking any food.” “The rapidity of development,” he continues, “has also great influence on the quantity of food which an animal requires. Thus the caterpillar, which grows very quickly, and must repeatedly throw off its integuments, during its continuance in the larva state, consumes a vast quantity of food compared with the size of its body; and hence we find it provided with a digestive apparatus of considerable size.”[9] Hence, too, the greater demand for food in infancy and youth when growth and activity are both at their height.

In thus insisting on regular bodily and mental activity as indispensable to the enjoyment of a good appetite and sound digestion, the attentive reader will not, I trust, be disposed to accuse me of inconsistency because, when treating of muscular exercise in the former volume,[10] I explained the bad effects, and inculcated the impropriety, of indulging in any considerable exertion immediately before or after a full meal. It is true, as there mentioned,[28] that exercise, either in excess or at an improper time, impairs the tone of the stomach; but it is not on that account the less true that bodily exertion when seasonably and properly practised, is the best promoter of appetite and digestion which we possess; and it is only under the latter conditions that I now speak of it as beneficial and even indispensable to health.

In a work like the present, it is obviously impossible to fence round every general proposition with the numerous limitations which an unusual combination of circumstances, or a departure from the state of health, might demand. And, even if possible, it would not be necessary, as the laws of exercise have been so fully explained in the volume alluded to, that their re-discussion here would unavoidably involve much repetition from its pages. At the same time, some warning remark may be required to prevent any risk of misconception, as it might otherwise be plausibly argued, for example, that there can be no such relation as I have alleged between waste and appetite, because a European perspiring under a tropical sun incurs great waste, and yet loses both appetite and digestive power. To render this a valid exception, it must be shewn that the European is intended by Nature to live in a tropical climate, and that the diet to which he accustoms himself is that sanctioned by experience as the best adapted for his constitution; because, if neither is the case, his condition under such influences must necessarily be more or less closely allied to the state of disease, and therefore beyond the sphere to which alone my remarks are meant to apply. But even in that instance there is less contradiction than might be imagined,[29] for the waste of the system being chiefly fluid, excites—not appetite, but its kindred sensation—thirst, to repair the loss by an unusual demand for refreshing liquids.

So true is it that the Creator has established a relation between action and nutrition, that when we attempt for any length of time to combine a full and nutritious diet with systematic inactivity, the derangement of health which generally ensues gives ample proof of the futility of struggling against His laws. Individuals, indeed, may be met with, who, from some peculiarity of constitution, suffer less than the generality of mankind from making the experiment; but even those among them who escape best, generally owe their safety to the constant use of medicine, or to a natural excess in some of the excretory functions, such as perspiration or the urinary or alvine discharges, by means of which the system is relieved much in the same way as by active exercise; and hence the remark made by Hippocrates, that severe perspirations arising during sleep without any other apparent cause are a sure sign that too much nourishment is made use of. In others, again, the day of reckoning is merely delayed, and there is habitually present a state of repletion, which clogs the bodily functions, and may lead to sudden death by some acute disease when the individual is apparently in the highest health. I am acquainted with several individuals of this description, who, in the absence of all bodily exercise, are accustomed to live very fully,—to eat in the morning a hearty breakfast, with eggs, fish, or flesh,—a good solid luncheon, with wine or malt liquor, in the forenoon,—a most substantial dinner,[30] with dessert and several glasses of wine, and afterwards tea and wine and water, in the evening,—and who nevertheless enjoy tolerably good digestion. But this advantage is generally only temporary, and even when permanent can scarcely be considered as a boon; because it is gained at the direct expense either of a very full habit of body and an unusual liability to abdominal congestion and all its attendant evils, or of frequent and profuse perspirations, and severe attacks of bowel complaint, endangering life; so that strictly considered such cases are no exceptions to the general rule.

It is, then, no idle whim of the physician to insist on active exercise as the best promoter of appetite and digestion. Exercise is, in fact, the condition without which exhalation and excretion cannot go on sufficiently fast to clear the system of materials previously taken in; and where no waste is incurred, no need of a fresh supply, and consequently, in a healthy state of the system, no natural appetite, can exist. It is therefore not less unreasonable than vain for any one to insist on possessing, at the same time, the incompatible enjoyments of luxurious indolence and a vigorous appetite,—sound digestion of a hearty meal, and general health of body; and no one who is aware of the relation subsisting between waste and appetite can fail to perceive the fact, and to wonder at the contrary notion having ever been entertained.

Among the operative part of the community we meet with innumerable examples of an opposite condition of the system, where, from excess of labour, a greater expenditure of energy and substance takes place than what[31] their deficient diet is able to repair. It is true that the disproportion is generally not sufficient to cause that immediate wasting which accompanies actual starvation, but its effects are nevertheless very palpably manifest in the depressed buoyancy, early old age, and shorter lives of the labouring classes. Few, indeed, of those who are habitually subjected to considerable and continued exertion survive their forty-fifth or fiftieth year. Exhausted at length by the constant recurrence of their daily task and imperfect nourishment, they die of premature decay long before attaining the natural limit of human existence.